Everything That Happens in Red Desert (52)

Seen enough today

This post contains extended discussion of suicide.

The final moments of Red Desert make me think of Dar Williams’s ‘Mark Rothko Song’, and vice versa.1 The song begins by describing a visit to a museum, where the speaker reacts instinctively to the abstract art they encounter:

The blue it speaks so full,

It’s like the beauty one can barely stand,

Or too much things dropped in your hand.

And there’s a green like the peace in your heart, sometimes,

Painted underneath the sheets of ashy snow.

And there’s a blue like where the urban angels go, very bright.

Now the Calder mobile tips a biomorphic sphere,

Then it swings its dangling pieces round to other paintings here.

This is like Sabeth’s ‘game of comparisons’ from Homo Faber (see Part 44). Everything is ‘like’ something, only now we are playing the game as Giuliana might, not with identifiable objects but with the vaporous colours of a Mark Rothko painting. The deliberately bad grammar of ‘too much things’ recalls Giuliana’s tendency to amalgamate the things and people she loves (so that they are ‘too much’ rather than ‘too many’), and the phrase ‘speaks so full’ is also grammatically awkward. ‘Fully’ and ‘many’ have one too many syllables for the chosen metre of this song, so they are abbreviated or replaced. These truncations are integral to what the speaker is saying about their response to abstract art: how that response exceeds their capacity to express it and is compromised by being inserted into a specific medium (such as song); or, from another point of view, how that response exceeds the expressive capacities of correct grammar and the spoken (as opposed to sung) word.

The verse moves from overwhelming beauty, to a transient sense of peace (‘sometimes’), to the cold burial sheets of ‘ashy snow,’ to a heaven that caters specifically to city-dwellers (too bright for rural angels, perhaps). There is something here of Giuliana’s turbulent emotional response to the world, and of Red Desert’s preoccupation with colour as a determinant of emotional states. This blue-green haven of peace, hidden under a layer of ash, is like the celeste e verde ceramics shop Giuliana planned to open on the greyed-out Via Alighieri (see Part 14). It is cooling and soothing, but tinged with unease. Somehow we cannot stay with it for more than a few seconds before other forces (or forces within the blue-green fantasy itself) wrench us away. We are buffeted between these intense colours until the nearby Calder mobile distracts us, and then distracts us from itself as well, seeming to point at other artworks. Williams evokes the sometimes contradictory experience of engaging with art. You have an intense, transcendent reaction, you try to understand or articulate it, then you give up and move on to the next masterpiece, the next thing. There is also a sense that, like Corrado faced with Giuliana’s final breakdown, the speaker has seen more than they wanted to and is desperate to be directed elsewhere.

In an interview, Williams explains that this verse was inspired by an encounter with a Rothko painting in the Fogg Museum at Harvard:

The painting was called Untitled (Blue, Green). And I thought, ‘What an ironic title, because it’s grey.’ But then as I stood there, it was very much blue-green, it was just underneath that kind of smog, and it hit me very strongly how melancholy that is, when people can show you so much of who they are, if you just pause, for just another second, and take them on their terms or look a little bit more closely. And I think I just started to write the song right there.2

Here is the Untitled (Blue, Green) currently listed at the Fogg Museum:3

The ashen quality Williams describes may have been a result of colour degradation, and the painting may have been restored since she saw it in around 1991 (or earlier). I wonder if it looked something like this Untitled (Green on blue):4

Or this one:5

Rothko himself would not have given the painting a title, so would not have expected viewers to find any irony in the name Blue, Green being attached to an image that appears predominantly grey. However, Williams’s attempt to reconcile the title with the painting creates an interesting dynamic in this first verse of her song. It adds an extra resonance to the phrase ‘painted underneath the sheets of ashy snow’: the blue and green suggest emotions that are buried under a seemingly cold or cremated exterior, but we also get the impression that the very act of painting has taken place ‘underneath the sheets,’ in a vulnerable and private space. In this way, the image expresses a melancholy truth about how we conceal our emotions, but also about how we fail to engage with people on their terms or to look closely enough at what they are showing us.

The next verse contrasts the colour that ‘speaks so full’ with an inexpressive, Corrado-like figure. The ‘you’ being addressed here may be the same Rothko painting the speaker was admiring before:

Your behaviour is so male,

It’s like you can’t explain yourself to me,

I think I’ll ask Renoir to tea.

For his flowers are as real as they are, all the time,

And the sunlight sets the furniture aglow.

It’s a pleasant time as far as people go – how far do they go?

Well his roses are perfect and his words have no wings.

I know what he can give me and I like to know these things.

Rationalising the shift towards ‘other paintings’ at the end of the first verse, the speaker explains why they suddenly feel frustrated by abstract expressionism and its refusal (or inability) to ‘explain itself.’ Now the game of comparisons draws a connection between the spectator-artwork relationship and the inter-personal relationship. The speaker would prefer to socialise with Renoir than with Rothko. The phrases ‘ask to tea’ and ‘pleasant time’ connote a conventional, archaic form of social relation, as dull and twee as it is perfect and predictable. We have left behind the game of comparisons and now things are as real as they are – and they are so ‘all the time,’ relentlessly, monotonously. Words have no wings and cannot go flying off to mean something else, as they threatened to do in the first verse. Then again, ‘what things are’ is not easy to determine. How real are the flowers? How far do people go? Does the speaker really know what people (or paintings, or roses, or words) can give them, or do they just ‘like to know these things’? That last word recalls the earlier phrase, ‘too much things.’ It is preferable to know and quantify the ‘things’ that pass between us and the people or objects we relate to. We like to know these things, and to know that there are not too much of them, even if this means they do not speak so full.

In the third verse, we find ourselves at an unnamed artist’s funeral (perhaps Rothko’s), hearing what people have to say about him. If the first and second verses presented competing voices in the speaker’s head, now there is a cacophony of voices engaged in that same effort to articulate a coherent response to something overwhelmingly complex. These voices mingle with the speaker’s, much as the opinions of others tend to blur into our own as we internalise them. Notice how the pronouns progress from ‘I’ at the start of this verse to ‘we’ at the end:

I met her at the funeral,

She said, ‘I don’t know what he meant to me,

I just know he affected me.

An effect not unlike his art, I believe.’

The service starts and we are in the know.

He had so much to say and more to show, and ain’t that true of life?

So we weep for a person who lived at great cost,

Yet we barely knew his powers till we sensed what we had lost.

We have already experienced a confusion between artworks and people, and now we encounter a person (‘her’) who is unnamed and abstract, whose connection to the speaker is not clear, and who conflates the deceased person with his art (and confesses to not understanding either). For as long as the commemorative service lasts, ‘we are in the know.’ The individual might say, as the woman at the funeral does, ‘I don’t know, I just know, I believe,’ but collectively ‘we are in the know.’ Like people trying to sound intelligent in a museum, we join forces to pretend that we understand who this person was. But our supposed appreciation of art and artist is a self-consuming paradox. He had more to ‘show’ than could be expressed or explained. We weep for him ‘yet’ we barely knew him. We ‘sense’ what we have lost, but we have also lost it and so cannot sense it, cannot ‘feel it anymore’ as Anna said to Sandro in L’avventura. Does the phrase ‘ain’t that true of life’ convey a plain-spoken truth or an empty, comfortable truism? Are these mourners more or less sincere than the squirming aesthete in the first verse?

The final verse returns to a museum setting, to a room with a single wall devoted to Mark Rothko:

A friend and I in a museum room.

She says, ‘Look at Mark Rothko’s side.

Did you know about his suicide?

Some folks were born with a foot in the grave – but not me, of course.’

And she smiles as if to say we’re in the know.

Then she names a coffee place where we can go, uptown.

Now the painting is desperate but the crowds wash away,

In a world of kind pedestrians who’ve seen enough today.

The scene-setting in the first line is refreshingly clear after the confusions of the first three verses. The speaker is in a museum with their friend, so we at least have a general sense of where we are and who is there with us. However, there is a stark contrast between this and the first verse. Instead of an individual having an emotional response to a painting and then distancing themselves from it, we have the friend asking the speaker to ‘look at’ the Rothkos (or rather, at the ‘side’ belonging to Rothko, the wall adorned by his works) but then immediately retreating from the paintings themselves, to focus on a biographical detail about the artist. This in turn prompts another folksy philosophical truism (‘Some folks were born with a foot in the grave’), and one that seems designed to contain and diminish the potentially disturbing nature of Rothko’s art. There is nothing too terrible here; some folks are just born to be depressed and suicidal; some folks, like Giuliana in Red Desert, are not equipped to deal with the world they are born into; we can smile philosophically about it.

This, however, does not do justice to the ambiguity of the friend’s comments. What does she mean when she adds, ‘but not me, of course’? Do we take this at face value, as an affirmation of her own strength and wellbeing? When she ‘smiles as if to say we’re in the know,’ is she inviting the speaker to share in this sense of wellbeing? ‘But of course I’m not like that, and neither are you.’ The phrase ‘of course’ underlines the normalising tone of this comment, but it also hints at another way of reading it. The friend may be speaking ironically: ‘Some folks are born with a foot in the grave, but of course I’m not talking about myself.’ Her knowing smile may be a kind of wink to the speaker, who is expected to pick up on this irony. The phrase ‘not me of course’ is sung to the same melody as the word ‘sometimes’ in the first verse (‘And there’s a green like the peace in your heart, sometimes’). Both phrases are sung with a kind of dying fall, and with a beat of ‘dead time’ between them and the next line. The peace in your heart is only there ‘sometimes,’ but you can only admit this in a small, furtive voice. You have to distance yourself from this suicidal artist, but you use the same small, furtive voice to do so (perhaps because you only feel distant from him ‘sometimes’).

This painting expresses something terrible about the human condition, but this thing cannot be spoken out loud. ‘Of course’ no one can admit to having seen it. Even the act of expressing it through this painting – the kind of painting that ‘can’t explain itself’ to the viewer – is made to seem like a prelude to or cause of the artist’s suicide. The friend looking at the painting cannot share her reaction to it, except through an ambiguous gesture. The speaker cannot even share their reaction with us, except through the ambiguous language and melody of their song. Albert Camus’s vision of art bringing the lonely esprit out of itself and into contact with other lonely souls (see Part 49) does not seem to apply here, any more than it does in Red Desert. The friend’s comment about what people are ‘born with’ shares something with Giuliana’s comment that ‘everything that happens to me is my life,’ including the ‘oh well’ undertone of Giuliana’s concluding, ‘that’s all [ecco].’ One’s dismal lot in life is to be accepted with a shrug – one should not talk (or even think) about it too much.

The friends abandon the museum for a ‘coffee place uptown,’ echoing the tea the speaker proposed to have with Renoir. Again, even while looking at the Rothko painting, the spectator is thinking of the less disturbing place they will soon retreat to. The friend ‘names’ the coffee place, identifying it and making it knowable. It is a place ‘where we can go.’ But the final lines of the song do not let us go, they keep us in the museum. ‘Now the painting is desperate.’ Williams sings the first syllable of ‘painting’ with a pained, lingering quiver, and the word ‘desperate’ with a breathless intensity. This painting cannot explain itself and those who look at it cannot communicate with each other, but the pain is there, desperate to be seen and acknowledged. Nonetheless, ‘the crowds wash away,’ the word ‘wash’ suggesting a cleansing but also obliterating action, the desperate painting sponged into blankness. The ‘world of kind pedestrians’ is also, by a play on words (and continuing the watery metaphor), a ‘whirl’, not unlike the congregation of mourners in the previous verse whose collective action normalised the artist’s torment into a set of easy platitudes. Like the adulatory eulogies that flatten out a person’s life once they are dead, the pedestrians have paid attention to this painting out of kindness, perhaps out of pity, but now they have ‘seen enough’ and they ‘wash away’ what they have seen (as well as themselves).

The idea that the painting itself is ‘desperate’ recalls Camus’s notion that a work of art can exceed its creator and follow through ‘to the bitter end’ what no human being can accomplish.6 This painting retains the desperation of the deceased painter, expressing what he could not express in his own person, or expressing it more vividly and intensely, and keeping that emotion alive on the wall of the museum. The speaker, their friend, and the other kind pedestrians feel this desperation as well, to one degree or another. It is the pain of someone who has been left behind, just as Giuliana has been left behind in the world of Red Desert. It is that part of myself that I leave in the dark (while smiling and saying, ‘not me, of course,’ although I know it is me), but that I cannot bear to look at for very long. Giuliana leaves the film and we are left staring at the factories, but her desperation and ours are still there in the image and in the soundtrack. We may have ‘seen enough today,’ but that word ‘today’ implies a tomorrow when these anxieties will return, and that word ‘enough’ implies that there is more than enough – that there is more to see, perhaps too much.

Mark Rothko’s son, Christopher, expresses mixed feelings about ‘Mark Rothko Song’. He sees it as symptomatic of a problem that has dogged his father’s posthumous reputation:

[T]hrough the suicide, he [created] an interference pattern through which most must pass to view his work and through which his fame will always be regarded. Has he indeed achieved fame or merely notoriety? Will songs laud him for the power of his paintings, or will they instead render art and artist a footnote to the sensation of his suicide?

In the case of Dar Williams’s song, I would suggest the answer must be both. For, as I have noted, the suicide would not generate ongoing fascination were it not for the appeal of Rothko’s artwork. And yet it is unlikely that my father would have featured in this song were it not for the suicide, despite the fact that the first stanza contains a very sensitive description of the emotive vocabulary of his work. […] Over the course of the song, Williams uses Rothko’s suicide as a gateway to looking at human personality and psychological defense, but those are subjects at best peripheral to the language of my father’s paintings. She equates the saturation of color in Rothko’s canvases with his own emotional saturation, a depth and excess of feeling that ends, consequentially, in suicide. This is quite a sophisticated undertaking in a four-stanza song, but we are still closer to the life than we are to the work, and once again, the tail has wagged the dog: the suicide is the causative factor, working retroactively to color the content of Rothko’ s artwork.7

It should go without saying that Christopher Rothko, who was six at the time of his father’s suicide, has every reason to feel frustrated (or indeed furious) with the discourse around this topic, which he has had to listen to for decades. If this frustration makes him unwilling to fully engage with a song that invokes his father’s suicide, that is fair enough.

But what he presents here is, I think, a mis-reading of ‘Mark Rothko Song’, and a very telling one in the context of his comments about Antonioni, which I will discuss later. He only quotes the first few lines of Williams’s final verse (from ‘A friend and I’ to ‘not me of course’), and does not engage with the fact that the reference to Mark Rothko’s suicide is made by the friend, not by the song’s primary speaker. To refer to the latter as ‘she’ and ascribe her comments to the author is also problematic, because this speaker may or may not be Dar Williams; if the third verse is indeed set at Rothko’s funeral, in 1970, it is worth noting that Williams was only three years old at that time. Her songs often function as character sketches – sometimes without specifying the speaker’s gender – and in this case the technique is integral to what the song is about. The voices that equate art and artist, that say he ‘lived at great cost,’ or that gossip about his suicide, are not to be taken at face value. But this is how Christopher Rothko takes them: to his mind, the song argues that his father felt ‘too much things,’ that he was like one of his own paintings, that he therefore ‘lived at great cost,’ and that the ultimate cost was suicide.

We are preoccupied with suicide, he suggests, because

it frightens us to our very core. So foreign and so close to home. Something we cannot imagine and which we can imagine too readily. The object so repulsive we cannot resist looking at it. […] [P]reoccupation with that which most disturbs us is reflected in the seemingly limitless tide of horror and violence in the majority of popular films made today. Treatment of even the most gentle themes is apparently incomplete without it. Somehow we feel compelled to watch all manner of horrific things we would never want any part of ourselves. […] [S]uicide touches our psyches in a truly profound place, but we turn it into theater.8

Those who read Mark Rothko’s art in terms of his suicide are seen, here, not so much as ‘kind pedestrians’ but as rubbernecking gawkers in search of a transgressive thrill, and again it is more than understandable that Christopher Rothko would see them in this way. No doubt this is what many (or even most) of them are. But he does not allow for the possibility of a spectator who is, or has been, suicidally depressed themselves, and who connects with Mark Rothko as a suicidal artist for this reason. He asks why we consider suicide to be so revealing:

Indeed, what other factor could be so obscuring? No one has firsthand knowledge of suicide – is there ultimately anything that can remain for us less knowable? And therein lies, I would venture, much of its fascination.9

No one has firsthand knowledge of death, but the same is not true of suicidal ideation or attempted suicide, and it is surely these experiences (and the feelings associated with them) that people are – sincerely and/or pruriently – fascinated by. Nor, to recall the terms of the previously quoted passage, is suicide entirely a matter of ‘imagination’ and ‘theatre’ for those who are or have been suicidal. Nor can it simply be called a ‘horrific thing we would never want any part of ourselves,’ because it is already a part of us and therefore something we need, and even want, to acknowledge, at least sometimes. Rothko raises legitimate concerns about the media’s aestheticisation of suicide, but the media artefacts under discussion here are (in my opinion, and in my experience) the kind that prompt greater openness, dialogue, reflection, and even help-seeking behaviours, all the more so because they foster an understanding of and empathy with despair. To put it more simply, I do not think I would be alive today without Red Desert and ‘Mark Rothko Song’.

Rather than saying that ‘it is unlikely that Mark Rothko would have featured in this song were it not for his suicide,’ it would be more accurate to say that Dar Williams would not have written the song at all were it not for her own then-recent experience of suicidal depression. It was this experience, in her early twenties, that prompted her to meditate on the ways in which that ‘desperate’ part of ourselves can go unseen, or can be obscured by the norms and clichés through which we tend to define ourselves:

I think that my depression, my suicidal ideation, was possibly the anger of my soul saying, ‘I’m here and you are doing everything you can to not pay attention to me.’ And it made me a very self-destructive person. […] There’s this thing that knows something in here, I’m not just what anybody wants me to be. And that saved my life.10

Far from suggesting that Mark Rothko’s over-saturated excess of feeling caused his suicide, Williams situates her own suicidal ideation within a culture of emotional repression, from which art (including Rothko’s) is a life-saving escape. Her song engages with but rejects the idea that ‘nothing can be less knowable’ than suicide. That repeated phrase, ‘we are in the know,’ is poised on a knife-edge between alienation and connection – between the sense that suicide is hopelessly distant from our understanding and the sense that it is something familiar that we can talk to each other about. The ‘friend and I in a museum room’ are so close to having that conversation, and they only fail to have it because they walk away from the painting. The painting’s desperation is also the speaker’s, and perhaps the friend’s. Crucially, it is an unresolved, unredeemed feeling we are left with as the song fades out. The loneliness of this feeling is not inflicted on us by the song: it is a loneliness we discover in the song, and/or that the song discovers in us. The result may seem like a paradox, and it is not an easy effect to describe in words, but the loneliness is assuaged (not cured) by virtue of being acknowledged. For a moment, we are the seer as well as the seen, and the mystery of this existential terror feels slightly less mysterious. Giuliana said, ‘There is something terrible in reality, and I don’t know what it is - no one will tell me.’ Now we can say, ‘There is something terrible in reality, and I think I understand it - I think someone else does too.’

Antonioni is said to have told Mark Rothko, ‘Your paintings are like my films – about nothing, with precision.’11 Christopher Rothko cites an alternate version of this comment (reported by Robert Motherwell), and then problematises it:

‘I film nothing, you paint nothing,’ [Antonioni] remarked. […] One can certainly understand what he meant – the open spaces, the unadorned abstraction, the aching search for meaning that marks both of their work. There is a phenotypic similarity in their best-known pieces that presents the viewer with an emptiness that must somehow be filled (Antonioni’s masterpiece The Red Desert embodies this sensibility most powerfully). But here the comparison breaks down, for while Antonioni (and I make no pretense of being a film scholar) presents us with a modernist crisis, a man-made world as vacuous as it is artificial, Rothko’s paintings, for all their reduction in means, are bursting with energy and alive with human spirit. The void they present is only a void of referents to the outside world, and this precisely because my father sought to remove the distractions and preoccupations of the physical realm. He wanted to shift our focus, and draw our attention to the inner world – the world of ideas and, most critically, the world of emotion. Rothko sought to speak as directly as possible to our inner selves, be it in a flood or a whisper – passion dampened by as few mediators as possible. He wanted to communicate with our most core human elements; to those aspects as common to our hunter-gatherer ancestors as they will be to our successors millennia from now.12

To say that Antonioni’s films are ‘about nothing’ in the sense that they present ‘a man-made world as vacuous as it is artificial’ makes him sound like a satirist and a moralist, as though Red Desert were La dolce vita. For Christopher Rothko, Antonioni exemplifies a tendency to focus too much on the topical, on ‘referents to the outside world,’ the ‘distractions and preoccupations of the physical realm.’ Such art could never be ‘bursting with energy and alive with human spirit’ as Mark Rothko’s was; to be that, art must ‘speak directly to our inner selves’ (not portray the outer world we live in) and ‘communicate with our most core human elements.’ Throughout his book, Christopher Rothko (drawing on his father’s ideas) frequently invokes the ‘universal’, the ‘essential’, and the ‘timeless’ as the proper concerns of great art. Some of the qualities he ascribes to his father’s work – a concern with the emotions of the inner self, a desire to engage directly with the viewer’s emotions through imagery – could equally be ascribed to Antonioni’s, but a concern with the empirically observable modern world is indeed something they do not share.

Here is a case in point. Christopher Rothko takes issue with the many critics who describe his father’s painted rectangles as ‘stacked’, and insists that they should instead be thought of as ‘floating’.13 By contrast, the barrels of nitric acid in the final shot of Red Desert are both ‘floating’ (as we see them through the telephoto lens) and ‘stacked’ (as we then see them through the wide-angle lens), constituting both a landscape of the mind and a very literal, tangible set of objects in 1963 Ravenna. And then, of course, we could swap them around: in retrospect we understand the blurs as representing stacks of barrels, but the blurs have also conditioned us to see the stacks as nebulous, floating entities. Rather than being directed away from the distractions of our physical environment towards our inner humanity, we are asked to see these two spheres of existence as locked in an uneasy, symbiotic relationship.

Antonioni does not, I think, believe in timeless or universal things. Even when he talks about an ‘absolute, mysterious reality,’ he frames it as a reality ‘that nobody will ever see,’ and goes on to imagine that any attempt to find it would result only in ‘the decomposition [scomposizione] of every image, of every reality.’14 Mark Rothko’s verdict on modernist artists, as summarised by his son, seems relevant here:

[They] make compelling visual images and stimulating intellectual arguments, but they forget to communicate on the emotional plane. Modern art […] is cynical in the way it breaks down the world of human experience – it tears apart but does not put back together.15

For me, art that breaks down and tears apart – that portrays the scomposizione that so fascinates Antonioni – is deeply affecting, while art that ‘puts back together’ tends to leave me cold. The breaking down and the tearing apart, and the sense that nothing will be whole again, are human experiences that take place ‘on the emotional plane,’ and they cannot be explored honestly under the pressure of having to transition into a more redemptive mode. We are not creatures with timeless, universal essences, but contingent entities, floating and stacked at the same time, dissolving in an equally contingent (stacked, floating) environment. You may find this worldview off-putting, but it is rooted in sincere feelings, and it is not necessarily ‘cynical’ because it happens not to chime with your own worldview.

In 1962, Richard Gilman wrote about Antonioni’s ‘nothing, with precision’ comment, saying that it was

[a]n alarming remark, calculated to throw the film theoreticians and the significance mongers into a cold sweat. […] Yet there is no reason to be dismayed. Antonioni’s films are indeed about nothing, which is not the same thing as being about nothingness. L’Avventura and La Notte are movies without a traditional subject (we can only think they are ‘about’ the despair of the idle rich or our ill-fated quest for pleasure if we are intent on making old anecdotes out of new essences). They are about nothing we could have known without them, nothing to which we had already attached meanings or surveyed in other ways. […] They are part of that next step in our feelings which art is continually eliciting and recording. […] It might be described as accession through reduction, the coming into truer forms through the cutting away of created encumbrances: all the replicas we have made of ourselves, all the misleading because logical or only psychological narratives, the whole apparatus of reflected wisdom, the clichés, the inherited sensations, the received ideas.16

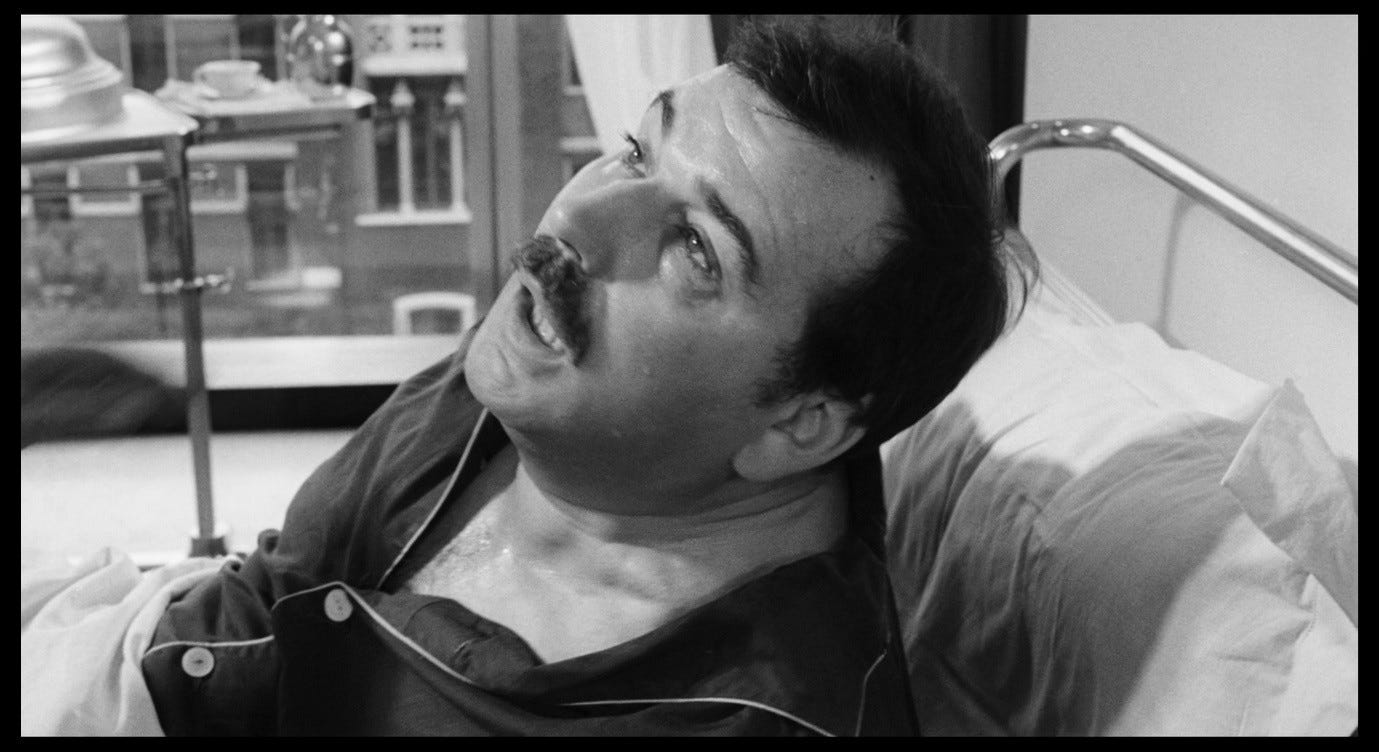

There is something lacking in Christopher Rothko’s description of Antonioni’s films as portraits of a vacuous, artificial world in a state of modernist crisis, and in Pauline Kael’s critiques of La notte and Red Desert for their focus on vacuous leisured characters (see Part 18). To describe such readings as ‘making old anecdotes out of new essences,’ as Gilman does, is especially resonant given Rothko’s emphasis on what is ‘essential’ in human nature. For Antonioni, human nature is always changing, always engaged in a chaotic dialogue with the world around us, and nothing we consider essential stays that way forever. Yes, this means that the ‘created encumbrances’ (as Gilman calls them) come to seem empty and artificial, but we sense this breaking-down of reflected wisdom and clichés through the emotional states of the characters. When we watch La notte, we are not detached observers of early-60s Milan, judging its vacuousness with a nihilistic cynicism. We recognise ourselves in Lidia, Giovanni, and Valentina, and recognise how their and our inner selves are shaped by these giant edifices and transparent/reflective surfaces. If, for whatever reason, you do not recognise yourself in these people, or do not empathise with their efforts to navigate their rapidly changing reality, La notte will seem cold and glum, devoid of ‘new essences,’ nothing more than an ‘old anecdote.’ To love the film, I think you need to start by connecting with its emotions: the awe and anxiety of the title sequence, Tommaso’s cry of pain on his death-bed, Lidia and Giovanni’s awkwardness when they visit him, and everything that follows.

Nonetheless, it would be obtuse of me to claim that La notte is an easy film to engage with on an emotional level. It is not surprising that some viewers find in it a surface-fixated study of modern vacuity and artifice. In some ways, Red Desert is even less accessible, and may seem even more cold-blooded on an initial viewing. Throughout this series, I have discussed the tension between the film’s empathy for Giuliana and its tendency to regard her from a distance. We are often made to identify with her but we also have the option of seeing her through the eyes of the robots, so to speak. Closely related to this is the tension between Antonioni’s fear of progress and his sense that progress should be embraced. The industrialised world Giuliana clashes with is, in his eyes, an inevitable stage in human development, and while this is terrifying it can also be beautiful. Some, like Giuliana (and probably like us), will be left behind by this new world order, but others will thrive. The final two shots of Red Desert reiterate this tension, by showing us first the Giuliana’s-eye view of the world (blurry, constricted, confused, frightening) and then the robot’s-eye view (clear, panoramic, ordered, impressive).

But when I hear those robotic cries echoing over the final cut to black, I cannot help thinking of the fading, vocalising choir at the end of ‘Mark Rothko Song’, whose repeated ‘aahh’ song also reminds me of the wordless song we have heard twice in Red Desert. Perhaps, contrary to what I argued in Part 51, the factories and the robot-choir are not saying, ‘Get out and don’t come back,’ but rather, ‘Don’t go – not just yet.’ The film is desperate, like Giuliana. The image and the soundtrack are desperate. The real-world industrial complex we are looking at is desperate. They all want us to keep looking, keep listening, keep engaging. The ‘kind pedestrians’ are literally pedestrians in the sense that they walk away – we walk out of the cinema – but are also ‘pedestrian’ in the pejorative sense. We have been ‘kind’ in paying attention to this tormented work of art, but we are also ‘kind’ in the sense that we are true to the more pragmatic aspects of our nature, true to the ‘world of kind pedestrians.’ In this world, when we are faced with suicidal depression like Rothko’s or Giuliana’s, the done thing is to look at it for a moment, offer a few well-meaning platitudes, and then make ourselves scarce. We live in a world that progresses, moves on, and washes away. But Dar Williams is saying that there is something vital in the painting and something terrible in the way we leave it behind. Likewise, there is something vital in Giuliana’s way of seeing the world and in the images and sounds this film has given us, but we (kind and pedestrian as we are) have a limited capacity to perceive this something or to understand it.

For me, the best thing about Red Desert is that it embraces the perspective of Giuliana. It offers no final consolation, no prospect of a cure, no specific reason to be confident about the future. The film is what Dar Williams would call an ‘honesty room’ – the title of the album on which ‘Mark Rothko Song’ appears – a safe space, and a brave space, in which we can explore the darkest and most seemingly inaccessible aspects of human experience. Having spaces like Red Desert in my life has helped me overcome the desire to end that life, and helped me come to terms with the depression that seems an inescapable component of that life. It gives me hope and makes me feel less alone because it says that hopelessness and loneliness can be expressed and understood. In ‘Mark Rothko Song’, the painting is desperate because it represents something important and needs to be seen. Everything that happens in Red Desert is Giuliana’s life, and that life – a fiction, but a reflection of something real – is important, and needs to be seen. The despair that remains isolated and unconsoled is a feeling we need to be able to empathise with, or at least acknowledge. If it is a feeling we know from personal experience, we also need to see it portrayed honestly in works of art, as we do in the final seconds of Red Desert. Even when Giuliana has left the frame and we have stopped ‘seeing’ her, some invisible, inaudible thing is still there, still desperate to be seen and heard. But the image is abruptly replaced with a black void, the robot-song is cut off in the middle of its ghostly, echoing cry, and we are alone again.

Thank you for reading.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Williams, Dar, ‘Mark Rothko Song’, The Honesty Room (independently released 1993, re-released by Razor & Tie 1995). The same recording of ‘Mark Rothko Song’, without the concluding fade-out, was included on Williams’s second (independently released) album, All My Heroes Are Dead (1991).

Avishai, Tamar, ‘Dar Williams, Singer-Songwriter’, The Lonely Palette (podcast), 07 October 2022

Rothko, Mark, Untitled (sometimes exhibited as Untitled (Blue, Green)) (1968), Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum, image taken from rothko.nga.gov

Rothko, Mark, Untitled (Green on blue) (1956), Art Museum of the University of Arizona, Tempe, image taken from arthive.com

Rothko, Mark, Untitled (Green on Blue) (1968), image taken from artchive.com

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 207. See further discussion in Part 49.

Rothko, Christopher, Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 238

Rothko, Christopher, Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 243

Rothko, Christopher, Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 238

Whitman, Beth, ‘Dar Williams – Singer-songwriter’, She’s Bold with Beth Whitman (podcast), 01 April 2019

Heathcote, Christopher, ‘When Antonioni Met Rothko’, Quadrant (January-February 2012), pp. 84-89; p. 84. In the light of my discussion of Camus and Sartre in previous posts, it is worth noting the following comments from Heathcote: ‘European art criticism was firmly under the sway of contemporary French Existentialism, and thereby inclined to construe [Rothko’s] vaporous works in a strikingly different manner. Far from being perceived as indicators for a potential immanence of the spiritual, for a slender thread of hope, those hazy abstractions were viewed as pictorial exemplars of a Sartre-style nothingness. Such disjunctions in interpretation are more common than we often realise. They frequently affect unfamiliar works of art introduced to a different culture, claims being made which are chiefly projections of the host community’s own values’ (p. 87). See also Lewis, Jo Ann, ‘Rothko: Not Nothing’, The Washington Post, 02 May 1998, who cites Rothko’s pronouncement that ‘There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. […] The subject is crucial, and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless.’

Rothko, Christopher, Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 6

Rothko, Christopher, Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 116

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Preface to six films’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 57-70; p. 63. Cooper translates the last sentence as, ‘Or perhaps, not until the decomposition of every image, of every reality.’ But the sentence uses the same ‘fino a’ construction as the previous one, which refers to the unveiling of successive layers of images: ‘Fino alla vera imagine’ means ‘Down to the true image,’ and then I think ‘fino alla scomposizione’ means ‘down to the decomposition.’ In other words, Antonioni is not imagining a time when someone will see that ‘true image,’ but rather imagining that peeling back these layers would not even reveal the truth but cause all images and realities to disintegrate. Italian text from Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), p. xiv. See Parts 31, 35, and 41 for further discussion of this passage.

Rothko, Christopher, Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 104

Gilman, Richard, ‘About Nothing – with Precision’, in Common and Uncommon Masks: Writings on Theatre, 1961-1970 (New York: Random House, 1971), pp. 30-37; p. 34. Originally published in Theater Arts 46.7 (July 1962), pp. 10–12.