Everything That Happens in Red Desert (49)

The artist and reality

In two separate interviews, Antonioni cited Camus’s prescription, from The Rebel, that an artist should be engaged in a ‘revolt against reality’ (or ‘actuality’).1 For Camus, this revolt entails a paradoxical rejection of and engagement with the world:

Art is an activity which exalts and denies simultaneously. ‘No artist tolerates reality,’ says Nietzsche. That is true, but no artist can ignore reality. Artistic creation is a demand for unity and a rejection of the world. But it rejects the world on account of what it lacks and in the name of what it sometimes is.2

He defines this as a process of ‘stylisation’ and explains its effect in the context of sculpture, using the same ecstatic tone we saw in The Myth of Sispyhus and The Stranger:

Sculpture does not reject resemblance of which, indeed, it has need. But resemblance is not its first aim. What it is looking for, in its periods of greatness, is the gesture, the expression, or the empty stare [regard] which will sum up all the gestures and all the stares in the world. Its purpose is not to imitate, but to stylize and to imprison, in one significant expression, the fleeting ecstasy [fureur] of the body or the infinite variety of human attitudes. Then, and only then, does it erect, on the pediments of riotous cities, the model, the type, the motionless perfection which will cool, for one moment, the fevered brow of man [qui apaisera, pour un moment, l’incessante fièvre des hommes].3

Art, for Camus, represents ‘stability imposed on incessant change,’ and ‘the reconciliation of the unique with the universal.’4 The sculptor lends to the infinitely variable human face a style, a perfection, and a significance, and the final effect appeases our incessant fever, lessening the torment we feel in the waterless desert. We may recall the importance that Hermann Broch placed on style in The Sleepwalkers, and his association between the modern age’s lack of style and its ‘singleness of purpose’ which gives to everything a defined, discrete identity (see Part 30). In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus uses the phrase unité de but de l’esprit, rendered in O’Brien’s translation as ‘the mind’s singleness of purpose,’5 but I think he is referring to a desire for ‘unity’ that is slightly different from the ‘singleness’ Broch was condemning. It is through style that an artist conjures unity out of the disorder of reality.

In the above-quoted passage about sculpture, Camus shows an optimistic faith in the power of art to capture something universal, the gaze (‘regard’) that will sum up all the gazes in the world. As we saw in Part 14, Antonioni’s take on sculpture is less optimistic. Lo sguardo di Michelangelo expresses that same desire for ‘stability imposed on incessant change,’ for a ‘reconciliation of the unique with the universal,’ but ultimately finds an instability even in these fixed, imprisoned stone images. The camera roams across the sculptures and cuts back and forth between them and Antonioni’s unstable sguardo, as though searching for an angle or a way of looking that will capture that ‘motionless perfection’ of which Camus speaks. But the camera, and the film, remain in constant motion, and the incessant fever is left unappeased. For Camus, art gives us a sense of what unites us; Antonioni exits the church alone, as he arrived, and leaves the statues in their state of cold isolation.

Camus does not conceive of art as a cure-all for the human condition, but he does see it as facilitating a type of communal cohesion even when it describes the alienating desert of the absurd:

[Art] does not offer an escape [issue] for the intellectual ailment [mal de l’esprit]. Rather, it is one of the symptoms of that ailment which reflects it throughout a man’s whole thought [pensée]. But for the first time it makes the mind [esprit] get outside of itself and places it in opposition to others [en face d’autrui], not for it to get lost but to show it clearly [d’un doigt précis] the blind path [la voie sans issue] that all have entered upon.6

Camus’s mal de l’esprit is like Antonioni’s malattia dei sentimenti, though more focused on thought than on feeling; certainly, in the case of Red Desert, Giuliana’s sickness closely resembles the condition Camus describes. She also finds her condition to be sans issue (literally ‘without end/exit’), and the film does what Camus says art should do, describing this condition precisely and showing how it reverberates through a person’s whole experience of life. But in Camus’s account, this process involves drawing the esprit out of its isolation and into a relation with others. For him, this does not entail a loss of self but a discovery of common ground: it turns out that everyone is on this same inescapable path, so in a sense we are not lost but found. As he argues in The Rebel:

In absurdist experience suffering is individual. But from the moment that a movement of rebellion begins, suffering is seen as a collective experience – as the experience of everyone. Therefore the first step for a mind overwhelmed by the strangeness of things is to realize that this feeling of strangeness is shared with all men and that the entire human race suffers from the division between itself and the rest of the world. The unhappiness experienced by a single man becomes collective unhappiness.7

This may remind us (on the one hand) of Irene Girard’s movement from individual grief to ‘collective unhappiness’ in Europa ’51, and (on the other hand) of Giuliana’s failure to bond with the striking workers at the start of Red Desert (see Part 6). Her encounter with that ‘movement of rebellion’ drove her back into solitude, back to the uninhabited slag-heap where she sensed she would end up, alone. Even the condemned protagonist in The Stranger is able to communicate something of his revelation about existence, in his tirade to the well-meaning priest who tries to console him. Giuliana’s equivalent is her quasi-confession to the Turkish sailor, upon whom her words make no impact at all.

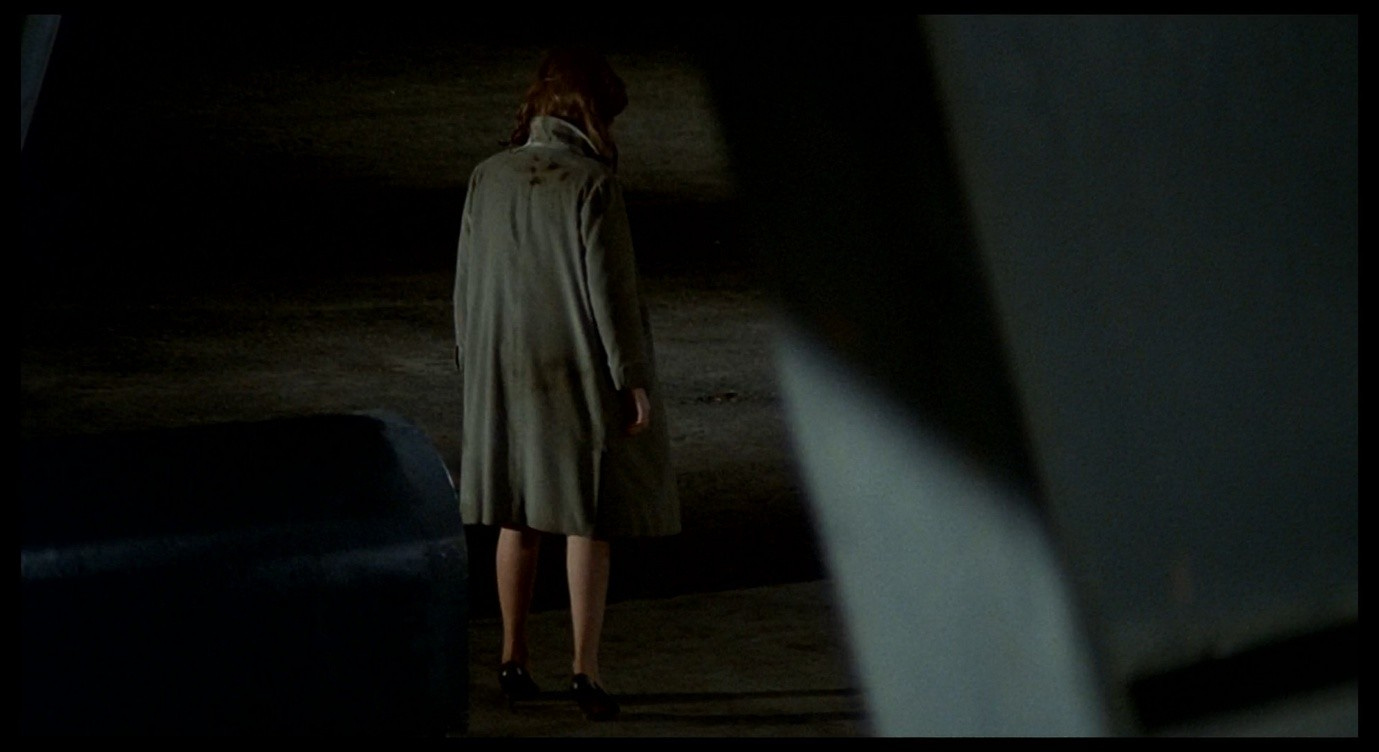

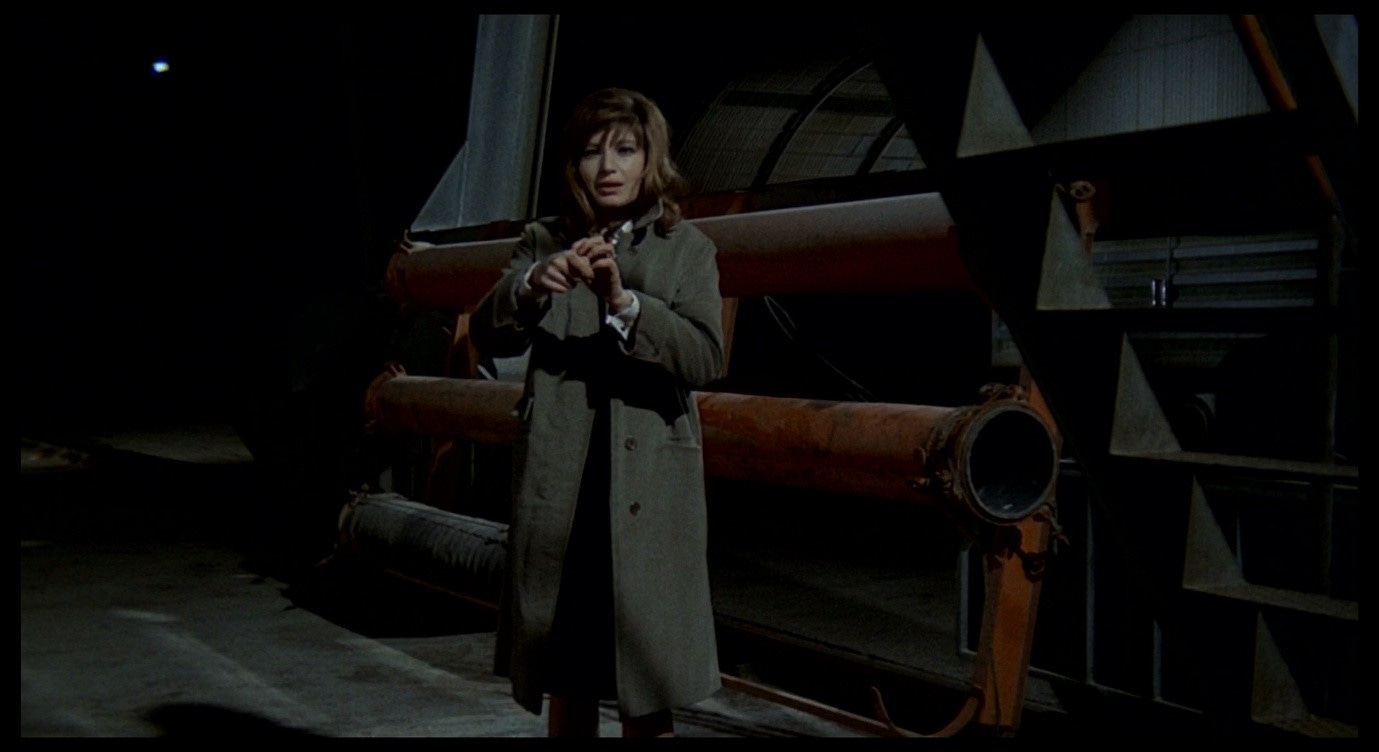

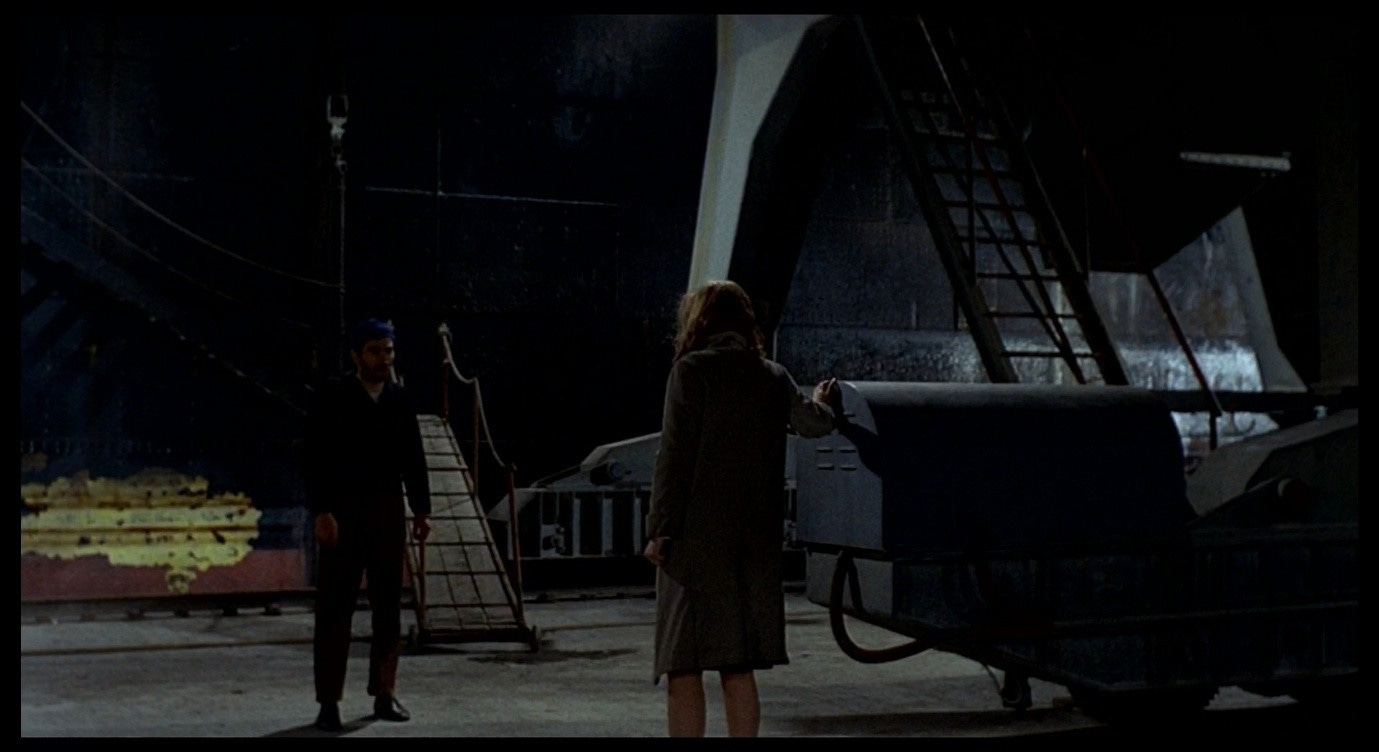

When Camus says that art points to a universal malaise d’un doigt précis, this makes me think of Antonioni’s famous comment that Mark Rothko’s paintings are ‘about nothing, with precision.’8 What Antonioni shows us so precisely is not a ‘path that all have entered upon,’ but the one by which Giuliana leaves the harbour. The camera is positioned behind the grey metal loading/unloading structure, which runs diagonally across the right half of the screen. As the camera tilts upwards, another part of the structure appears in the top-left corner.

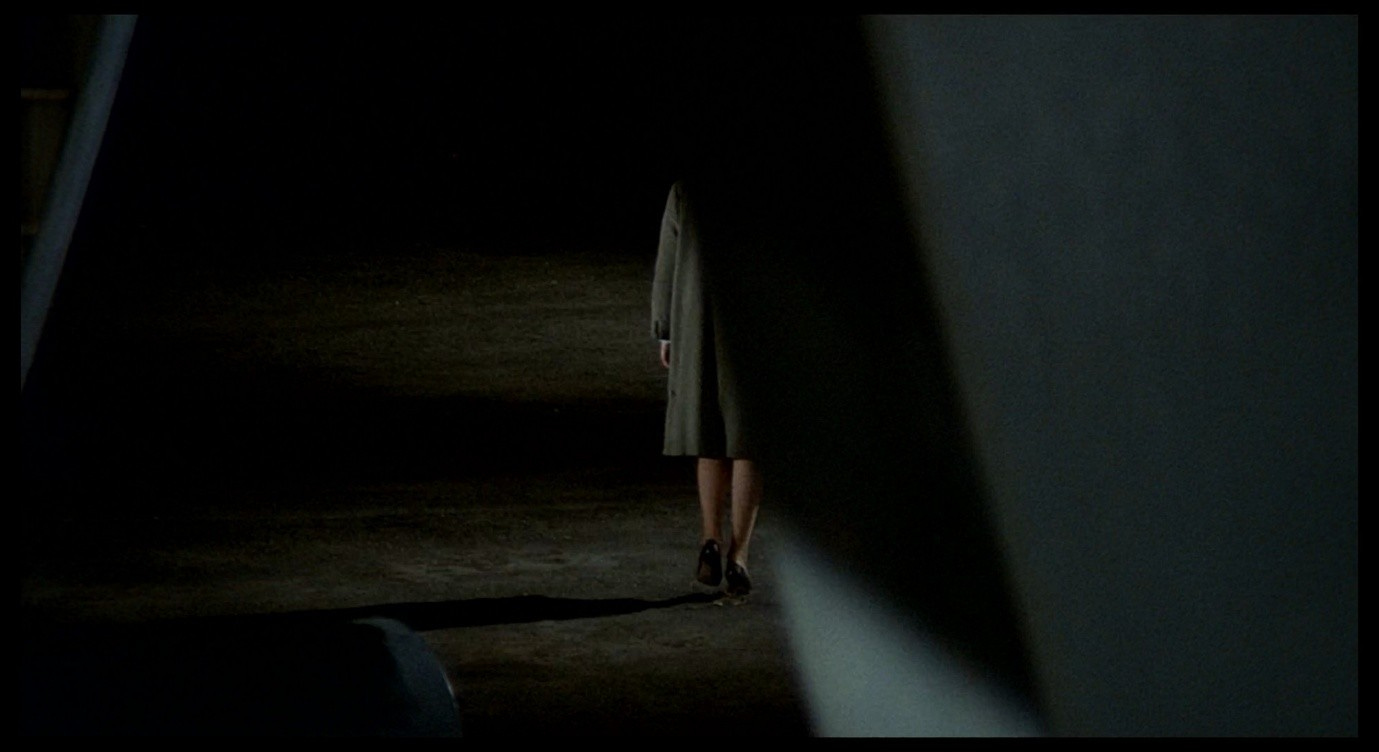

Like the downwards tilt at the start of the harbour sequence, this camera movement emphasises Giuliana’s smallness in relation to the structures around her, but in this case it also underlines the ‘framing’ effect. With the added diagonal in the top-left corner, Giuliana’s portion of the image becomes almost triangular, an ever-narrowing frame. Pools of light and shadow alternate along the ground. Giuliana walks slowly from light into shadow, her body disappearing behind the grey blur on the right. For a moment her shadow remains visible, but then it too is consumed by the shadow she has just walked into.

The final shot of Corrado was also timed to end on the disappearance of his shadow, as it moved out of frame, and I argued that his ‘journey into the darkness’ reflected his decision not to see or engage with what Giuliana was bringing to light (see Part 44).

When Giuliana leaves the docks, she does not simply walk out of the frame, she becomes part of a shadow. As when she was abandoned by Corrado, or by Ugo, there is a sense that she is left in obscurity, alone and unseen.

To watch Red Desert is not to find one’s esprit taken out of itself and brought into relation with other, similarly afflicted, spirits. Some of us may recognise something of ourselves in Giuliana’s condition, but the film underlines that it is her condition, not a universal experience. If you prick her, you will not feel pain, and everything that happens to her is her life (not to us, not our lives). For Camus, the malady is as inescapable as its universality; we cannot get off the path, but we also cannot help but walk alongside the rest of humanity. For Antonioni, the path is sans issue in the sense that it is inescapably solitary. I cannot leave my path and I cannot join yours. Red Desert is, after all, the story of someone left behind by the rest of the world. If in one sense Giuliana resembles Camus’s heroic rebel, living defiantly on that dizzying precipice, finding a way to survive in the desert and ‘to examine closely [its] odd vegetation,’9 in another sense she is merely the bleeding body left to rot in the sand, with no oases – and therefore no vegetation – in sight.

Camus argued that a ‘true work of art is always on the human scale,’ and that it should not suffer from ‘overloading and pretension to the eternal’; it should be a ‘fecund work because of a whole implied experience, the wealth of which is suspected.’10 A novelist should write

in images rather than in reasoned arguments […] convinced of the uselessness of any principle of explanation and sure of the educative message of perceptible appearance. […] The novel in question is the instrument of that simultaneously relative and inexhaustible knowledge, so like that of love. Of love, fictional creation has the initial wonder and the fecund rumination. […] I want to liberate my universe of its phantoms and to people it solely with flesh-and-blood truths whose presence I cannot deny.11

Giuliana’s ‘everything that happens’ speech, and her insistence on the incommunicability of her own flesh-and-blood truths, show the extent to which Red Desert meets Camus’s artistic ideal. Our protagonist is not overloaded with symbolic or emblematic significance, but is instead a highly idiosyncratic individual whose experience of life is described – without ever being fully explained – in the course of the film. The film’s imagery is all geared towards capturing this individual’s perceptions and feelings, and if it prompts (in the viewer) thoughts and feelings on larger topics, the effect will be all the richer because the film presents human-scale images rather than reasoned arguments.

The link between artistic creation and love, in the above-quoted passage from Sisyphus, is especially significant in relation to Antonioni, for whom art, existential philosophy, and erotic love go hand in hand. In The Rebel, Camus’s comments on transience and love provide another point of comparison and contrast with Antonioni. Speaking of our desire to give our lives unity and meaning, Camus argues that

everyone tries to make his life a work of art. We want love to last and we know that it does not last; even if, by some miracle, it were to last a whole lifetime, it would still be incomplete. Perhaps, in this insatiable need for perpetuation, we should better understand human suffering, if we knew that it was eternal. It appears that great minds are, sometimes, less horrified by suffering than by the fact that it does not endure. In default of inexhaustible happiness, eternal suffering would at least give us a destiny. But we do not even have that consolation, and our worst agonies come to an end one day. One morning, after many dark nights of despair, an irrepressible longing to live will announce to us the fact that all is finished and that suffering has no more meaning than happiness.12

In L’avventura, Anna’s disappearance causes Sandro and Claudia a certain amount of suffering, but this fades quickly, and it is this dissipation of suffering that disturbs Claudia (all the more so because it does not seem to disturb Sandro). Claudia resists that ‘irrepressible longing to live,’ holding onto her grief, and then onto her guilt when she ceases to grieve. It is the connection with Anna – hers and Sandro’s – that she wants to keep alive. But as Camus says:

The desire for possession is only another form of the desire to endure; it is this that comprises the impotent delirium of love. No human being, even the most passionately loved and passionately loving, is ever in our possession. On the pitiless earth where lovers are often separated in death and are always born divided, the total possession of another human being and absolute communion throughout an entire lifetime are impossible dreams. […] The shame-faced suffering of the abandoned lover is not so much due to being no longer loved as to knowing that the other partner can and must love again.13

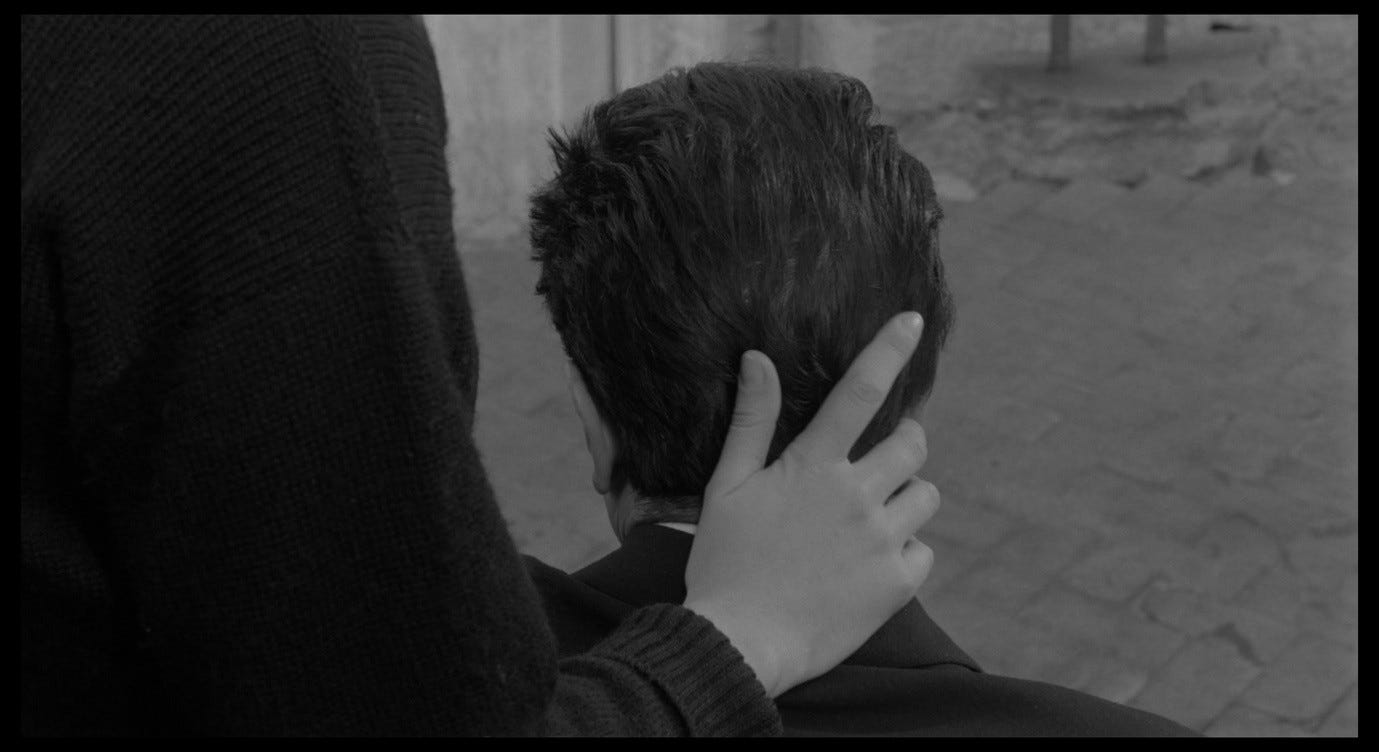

Aldo in Il grido is an example of Camus’s abandoned lover, struggling to come to terms with the moving-on process that operates not only in his relationship with Irma, but in every past, present, and future relationship. Claudia and Sandro, in L’avventura, suffer from the ‘must love again’ imperative: because Sandro moves on from Anna, he will move on from Claudia as well; because she recognises this same emotional transience in herself, Claudia embraces Sandro at the end of the film, but in a tentative way (touching his hair) that emphasises the fragility of the bond between them.

At the root of Camus’s discussion of transience is the idea that ‘lovers are often separated in death and are always born divided.’ In Red Desert, Giuliana tells the sailor that although she is not separated from her husband, their bodies are separate. Suffering does not endure and neither does love; the desire to endure and to possess a loved one are the same thing; when Anna disappears, her loved ones will love again; if you prick Giuliana, you won’t suffer. The transience of love and suffering are inextricable from the ‘separateness’ Giuliana refers to: the bodies are separate because they are transient.

Camus relates this problem back to the absence of unity and style that art is supposed to remedy:

Life, from this point of view, is without style. It is only an impulse which endlessly pursues its form without ever finding it. Man, tortured by this, tries in vain to find the form which will impose certain limits between which he can be king. […] As in those pathetic and miserable relationships which sometimes survive for a very long time because one of the partners is waiting to find the right word, action, gesture, or situation which will bring his adventure [aventure] to an end on exactly the right note, so everyone proposes and creates for himself the final word. […] This passion which lifts the mind above the commonplaces of a dispersed world, from which it nevertheless detaches itself [dont il ne peut cependant se déprendre, which I think means ‘from which it cannot, however, detach itself’], is the passion for unity. It does not result in mediocre efforts to escape, however, but in the most obstinate demands.14

This image of humanity, tortured by an impulse to seek out ‘form’ and ‘style’ that will give unity to existence, recalls Antonioni’s Cannes statement, in which he pictures humanity as suffering from the outdated moral codes (or forms) of the modern age, following confused erotic impulses that make it unhappy.15 Lidia and Giovanni, in La notte, are stuck in the kind of ‘pathetic and miserable relationship’ that Camus describes: Lidia attempts to end the marriage but offers no ‘final word’ that will lend it a sense of unity, and Giovanni refuses to accept what she is telling him. Lidia does not seem to have that passion that would lift her ‘above the commonplaces of a dispersed world.’ Perhaps she is engaged in what Camus would call a ‘mediocre effort to escape,’ but this is precisely the kind of un-edifying and futile experience that Antonioni focuses on, and that he does not dismiss as mediocre.

The passion Camus describes results, he says, not only in ‘obstinate demands,’ but in true works of art:

unity in art appears at the limit of the transformation which the artist imposes on reality. It cannot dispense with either. This correction which the artist imposes by his language and by a redistribution of elements derived from reality, is called style and gives the recreated universe its unity and its boundaries. It attempts, in the work of every rebel, and succeeds in the case of a few geniuses, to impose its laws on the world. ‘Poets’, said Shelley, ‘are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.’16

Antonioni, filming in real locations but re-painting and re-distributing their elements, transforms reality in the way that Camus describes. But what laws does he thereby impose on the world, and what unity appears as a result of this transformation? A great novelist, in Camus’s eyes, creates characters who ‘pursue their destinies to the bitter end’ and ‘complete things which we can never consummate’; the writer’s stylisation of reality conjures a sense of unity through ‘the ideal delineation of faultless prose.’17 Camus uses the example of Mme de La Fayette, writing La princesse de Clèves as an idealised portrayal of her own emotional agonies, one that she herself could not experience:

The difference is that Mme de La Fayette did not go into a convent and that no one around her died of despair. No doubt she knew moments, at least, of agony in her unrivalled passion. But there was no dénouement.18

Art, Camus says, produces ‘tentative trembling symbols of human unity,’ challenging the discord of creation by presenting itself ‘as an entirety, as a closed and unified world.’19 But what sort of consummation does Giuliana experience at the end of Red Desert? Antonioni is known as a meticulous artist, but are his films intended to be faultless, ideal, closed and unified entireties? Does Red Desert contain any symbols of human unity, even tentative and trembling ones?

I have previously argued that Antonioni may identify with Corrado, whose philosophy echoes comments the director made in interviews (see Part 21), and who embodies a kind of blindly functional inexpressiveness that Antonioni tends to associate with his own gender (see Part 39). Women, he argued, are subtler filters of reality and better at expressing emotions.20 In this sense, Giuliana is the kind of protagonist Camus looks for in a great novel, completing and consummating an emotional journey that the artist himself cannot follow through to the bitter end. Corrado’s departure, just before the shipyard sequence, mirrors the author’s own retreat from the dizzying precipice that Giuliana is about to peer over. But there is perhaps another kind of retreat in the idealised consummation that Camus refers to. In his concluding remarks about Sisyphus – the mythological figure condemned forever to push a rock up a mountain only for it to roll back down again – Camus strikes an optimistic note:

At that subtle moment when man glances backward over his life, Sisyphus returning toward his rock, in that slight pivoting he contemplates that series of unrelated actions which becomes his fate [cette suite d’actions sans lien qui devient son destin], created by him, combined under his memory’s eye and soon sealed by his death. […] Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must [Il faut] imagine Sisyphus happy.21

Why must one imagine Sisyphus happy? What if the events of a person’s life are not created by them, combined by their memory, or sealed (and thereby granted unity and meaning) by their death? What if Meursault in The Stranger did not open his heart to the benign indifference of the universe, did not find any solace in remembering the details of his life, and indeed were not about to be executed? What if he were facing many more years of the same actions sans lien, events without any connective links between them, relation-less relationships with the other strangers in his life?

For Meursault, those seemingly link-less events ‘become his destiny,’ and are pictured as a breeze that has been blowing towards him since he was born, as if there were some cosmic (or at least meteorological) order to his fate (see Part 48). For Giuliana, it is a question of ‘everything that happens to me [tutto quello che mi capita],’ the Italian verb capitare connoting the same sense of random chance as the English word ‘happen’. And all these things that happen to her do not become her destiny, they simply are her life. In place of the Stranger’s blissed-out Sisyphean happiness, we have Giuliana’s ecco and her awkward shuffling away from the Turkish sailor. Ecco: there it is, that’s all.

This is the precipice we are afraid to peer over. It was Mme de La Fayette, not the Princesse de Clèves, who experienced to the bitter end what the ‘ideal delineation of faultless prose’ could never capture. It is Giuliana, more than Meursault, who delineates – in an appropriately non-ideal, bathetic, and deeply unsatisfying way – the sensation of chronic estrangement. Red Desert is not a closed and unified world, but a compromised work of art that spills into and merges with the real world, its locations resisting the artist’s attempts to impose laws upon them, the machines and structures and non-professional actors remaining defiantly themselves. Antonioni follows Camus’s principle about the artist’s revolt against reality, but unlike Camus he lets reality win. There is something terrible in reality, and we don’t know what it is, and no one will tell us, and its senseless chaos will always triumph in the end.

Antoine, the protagonist of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, experiences symptoms that are strikingly similar to Giuliana’s in Red Desert, and that are often figured in terms of encroaching smoke or swirling colours. In the context of the present discussion, what is most interesting is Antoine’s commentary on ‘reality’, for instance in the following passages where he distinguishes the real from the unreal and feels menaced by the latter:

I looked around me for a support, for a defence against my thoughts. There was none: little by little the fog had broken up, but something disquieting still lingered in the street. Perhaps not a real menace: it was pale, transparent. But it was precisely that which ended up by frightening me. […] The fog had invaded the room: not a real fog, which had gone a long time before, but the other fog, the one the streets were still full of, which was coming out of the walls and pavements. A sort of unsubstantiality of things. […] Nothing looked real; I felt surrounded by cardboard scenery which could suddenly be removed.22

This is how Giuliana feels when she looks at her blurred environment or at a street painted grey. Both those effects are products of an ‘art’ that, to use Camus’s phrase, ‘rejects the world on account of what it lacks and in the name of what it sometimes is.’23 Such images represent a demand for unity and coherence, but a perversely artificial one. Behind them, we sense a pale, transparent menace, an unsubstantiality of things that seeps from every surface, and we feel – like Clara among the deconstructed sets in La signora senza camelie – surrounded by structures that have been put there deliberately and could just as easily be taken away.

This feeling in turn transitions into an anguished sense of being both trapped and lost in the present:

I looked anxiously around me: the present, nothing but the present. Light and solid pieces of furniture, encrusted in their present, a table, a bed, a wardrobe with a mirror – and me. The true nature of the present revealed itself: it was that which exists, and all that was not present did not exist. The past did not exist. Not at all. Neither in things nor even in my thoughts. True, I had realized a long time before that my past had escaped me. But until then I had believed that it had simply gone out of my range. […] Now I knew. Things are entirely what they appear to be and behind them … there is nothing.24

Cardboard scenery is what it appears to be and nothing more. A film image is insubstantial in the same way. Behind them there is nothing, as Clara sees when she looks at the film-image of herself.

Such insubstantial things are embodiments of the ‘presentness’ that Antoine experiences. The unity and coherence that are imposed on reality (by art) are merely contingent surfaces that are here now, in the present, but were not here in the past and will not be here in the future. Anticipating Giuliana’s scratching of one hand with another when she says, ‘If you prick me, you don’t suffer,’ Antoine describes his nightmare of existence with reference to this same gesture:

I feel my hand. It is me, those two animals moving about at the end of my arms. My hand scratches one of its paws with the nail of another paw.25

Humanity itself has become one of those arbitrarily imposed meanings: Antoine and his limbs might as well be called animals, his hands paws. He could also be describing Giuliana’s crisis in the harbour when he says:

I want to leave, to go somewhere where I should be really in my place, where I would fit in … but my place is nowhere; I am unwanted.26

Or when he arrives at a kind of resignation regarding his illness:

I have achieved my aim: I know what I wanted to know; I have understood everything that has happened to me since January. The Nausea hasn’t left me and I don’t believe it will leave me for quite a while; but I am no longer putting up with it, it is no longer an illness or a passing fit: it is me.27

To return to Camus’s formulation, this is like saying, ‘I am Mme de La Fayette, not the Princesse de Clèves.’ Antoine cannot situate himself inside a structured narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. He cannot see himself as a coherent human being with a meaningful identity who will, like Sisyphus returning to his rock, feel happy about the string of events that constitute his existence. To exist, for Antoine, means sensing those ‘animals’ – his own hands – scratching at one another, and acknowledging that this sickeningly alienated experience is ‘me’. If you scratched him, you would not suffer, and this impossibility of a relation between you and him is like the impossibility of relating his experiences to one another in the form of a narrative.

Antoine’s ex-lover, Anny, describes her own strategy for coping with existence:

‘I live in the past. I recall everything that has happened to me and I arrange it. From a distance, like that, it doesn’t do any harm, it might almost take you in. Our story is all quite beautiful. I add a few touches here and there and it makes a whole string of perfect moments. Then I close my eyes and I try to imagine that I’m still living in it.’28

Anny’s reverie is a way of rejecting the present-ness that would otherwise torment her. Just as she closes her eyes to the here-and-now – to the cardboard walls and the unreal fog – so she pretends that she is not here now, but rather that she is inhabiting that string of perfect moments. Giuliana’s ‘everything that happens’ is a little like that string, in that it gathers all the events and happenings together. But it also insists on the inescapability of the present: everything that happens to me is my life. Giuliana cannot close her eyes to this, and insofar as she is attempting to clutch at a string-of-moments, this attempt quickly falters when she shrugs and says ecco and stumbles away.

At the end of Nausea, Antoine hopes to apply art to reality and achieve something like the consolation of Camus’s Sisyphus. He proposes to write down his story, to turn it into the very novel we are just about to finish reading:

A book. Naturally, at first it would only be a tedious, tiring job, it wouldn’t prevent me from existing or from feeling that I exist. But a time would have to come when the book would be written, would be behind me, and I think that a little of its light would fall over my past. Then, through it, I might be able to recall my life without repugnance. Perhaps one day, thinking about this very moment, about this dismal moment at which I am waiting, round-shouldered, for it to be time to get on the train, perhaps I might feel my heart beat faster and say to myself: ‘It was on that day, at that moment that it all started.’ And I might succeed – in the past, simply in the past – in accepting myself.29

The act of artistic creation, in itself, is part of the Nausea, because it always takes place in the present. What Antoine looks forward to is the moment when the string will have formed in its entirety and he can look back on it as a completed narrative. Now he ‘waits for it to be time to get on the train’: he is in one present moment, waiting for (and nauseated by the prospect of) another present moment when it will be time to get on the train. One day, he will recall this moment and see it instead as the start of an adventure, himself as the hero of a novel, like Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain saying, ‘This is where I started.’

But there is one more paragraph at the end of Nausea:

Night is falling. On the first floor of the Hôtel Printania two windows have just lighted up. The yard of the New Station smells strongly of damp wood: tomorrow it will rain over Bouville.30

Antoine exists in the present, nothing but the present. Just as there will come a moment when it is ‘time to get on the train,’ so in this moment when night falls it is time to switch on the lights, like the street-lamps flickering on at the end of L’eclisse.

There might be room for a cause-and-effect narrative in the atmospheric conditions: today it rained and so the yard smells of damp wood; tomorrow it will rain again and the smell will persist or intensify. But Antoine rejects this opportunity. Even though he uses a colon to link the damp smell and the rain, he does so in a way that subverts cause and effect. The wood does not smell damp because it will rain tomorrow, nor will tomorrow’s rain be caused by the damp-smelling wood. There is the present damp smell now: tomorrow there will be rain. These are just things that happen, and they are Antoine’s life.

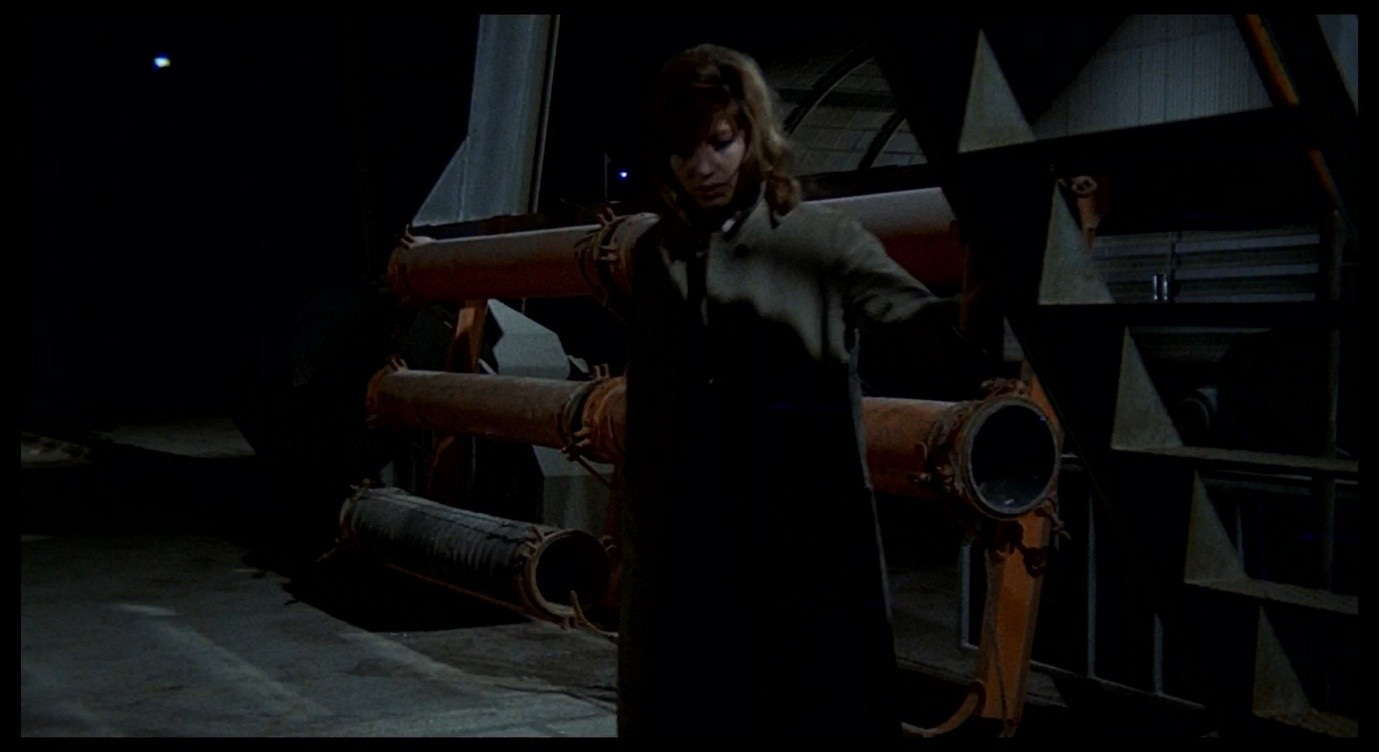

There is something like this triumph of dreary mundanity in the moment after Giuliana finishes her speech. Rather than making a dignified exit, she has to edge awkwardly past the harbour machinery and retreat from the sailor and his baffled protests.

This is another thing that happens to her, and this is her life. ‘I don’t understand,’ says the sailor repeatedly, in a language Giuliana cannot understand. The bodies are separate, so are the lines of dialogue exchanged between her and the sailor – separate, present utterances that are not integrated into a conversation – and so are the events that happen to her.

Next: Part 50, Re-inserted in reality.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

‘A talk with Michelangelo Antonioni on his work’ in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; p. 27. Labarthe, André, ‘A conversation with Michelangelo Antonioni’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 133-140; p. 133.

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 198

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 201. French text from L’homme révolté (Paris: Gallimard, 1951), p. 221.

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 202

Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), trans. Justin O’ Brien (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 71

Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), trans. Justin O’ Brien (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 70. French text from Le mythe de Sisyphe (Paris: Gallimard, 1942), p. 36.

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 9

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 54

Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), trans. Justin O’Brien (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 10

Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), trans. Justin O’ Brien (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 71

Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), trans. Justin O’ Brien (London: Penguin, 2013), pp. 73-74

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 205

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 206

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 206. French text from L’homme révolté (Paris: Gallimard, 1951), p. 225.

‘A talk with Michelangelo Antonioni on his work’ in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; pp. 33-34. The Cannes statement is quoted in full as part of this interview, and is also available on the Criterion website.

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 212

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 207

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 207

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 211

Tornabuoni, Lietta, ‘Myself and cinema, myself and women’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 185-192; p. 191. Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘A documentary on women’, in Unfinished Business, trans. Andrew Taylor (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 111-115; pp. 113-114.

Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), trans. Justin O’ Brien (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 89. French text from Le mythe de Sisyphe (Paris: Gallimard, 1942), p. 47

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), pp. 90-92

Camus, Albert, The Rebel (1951), trans. Anthony Bower (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 198

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 115

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 118

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 146

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 151

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 182

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 212

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Nausea (1938), trans. Robert Baldick (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 212

Regarding the topic of the article, does this 'stylisation' imply finding a deeper truth beyond imitation, maybe like an algorithm's abstraction? Fascinating analysis.