Everything That Happens in Red Desert (41)

The transformation

This post contains brief references to rape and spoilers for Enemy and The House of Mirth.

We have arrived at the most dream-like part of Red Desert. Lapsing into a state of semi-consciousness, we see the world around us consumed by blackness, then we see it taken over by anonymous, writhing bodies, then we see it taken over again by the colour of those bodies. This dialogue-free sequence is, like a dream, richly allusive but resistant to ‘definitive’ readings. It has been interpreted in drastically different ways by critics, which in itself is indicative of what the scene is about. Something in the interaction between Giuliana and Corrado makes the film become confused and inarticulate, and prompts it to express itself in ways that are as outlandish as they are vague. This will inevitably suggest different meanings to different viewers. For me, of course, the scene is about horror and despair.

After Giuliana’s brief frenzy in the armchair and her momentary glance into the camera-lens, we cut to a perspective from the other side of the chair. Giuliana leans forward over Corrado’s back – his head appears to be resting on her lap – and then she falls backwards and reclines against the back of the chair.

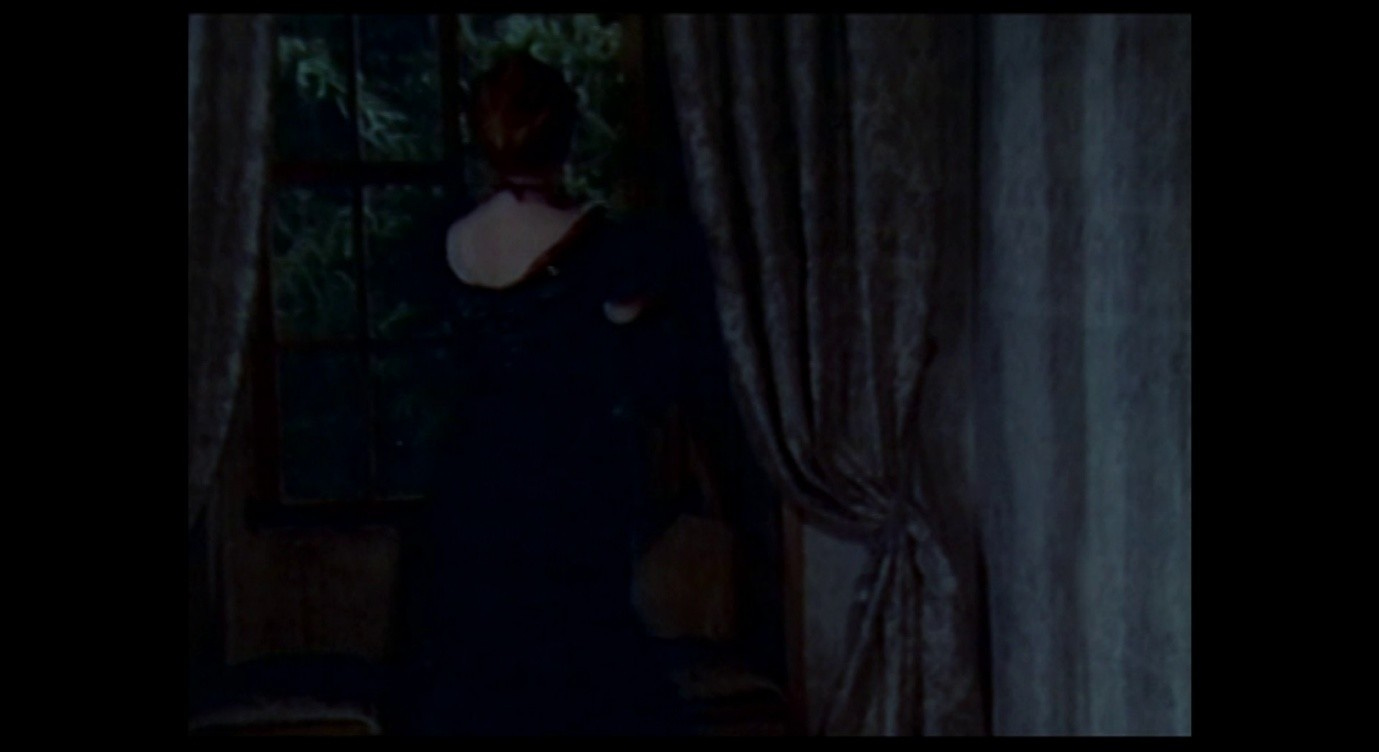

Throughout this scene, she has oscillated between frenzy and lassitude, between anxiety and depression. From now on, for the rest of the hotel-room sequence, her movements will be slow and languid. After reclining against the chair, she stands up and disappears out of the frame, and the camera tilts up towards the bed.

The shot may obliquely suggest that Giuliana exercises some agency here and literally ‘goes to bed,’ in order to have sex with Corrado. But this is only suggested, not clearly depicted. We do not in fact see where Giuliana goes. In this shot, her face is directed away from the camera, so she is once again reduced to her red hair. After allowing us that brief moment of ambiguous connection when she looked right at us, the film is now making her feelings opaque.

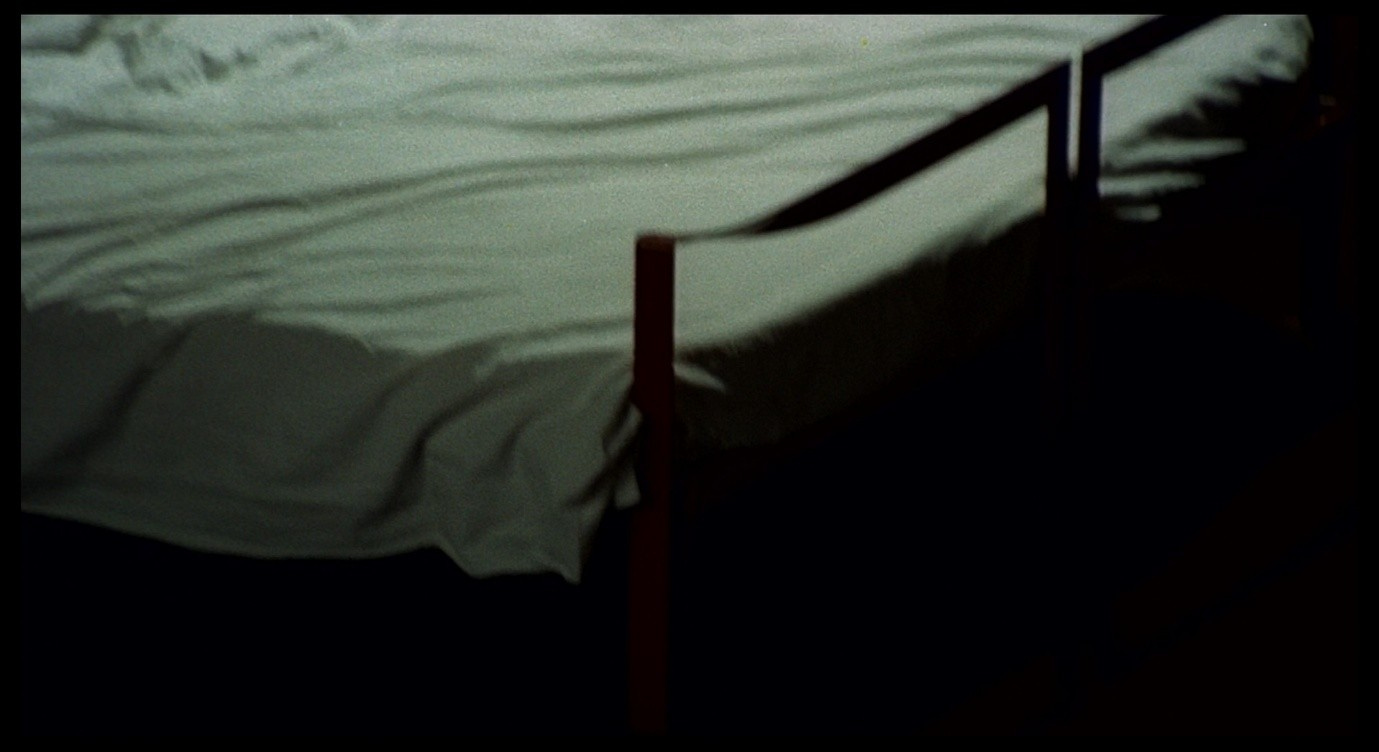

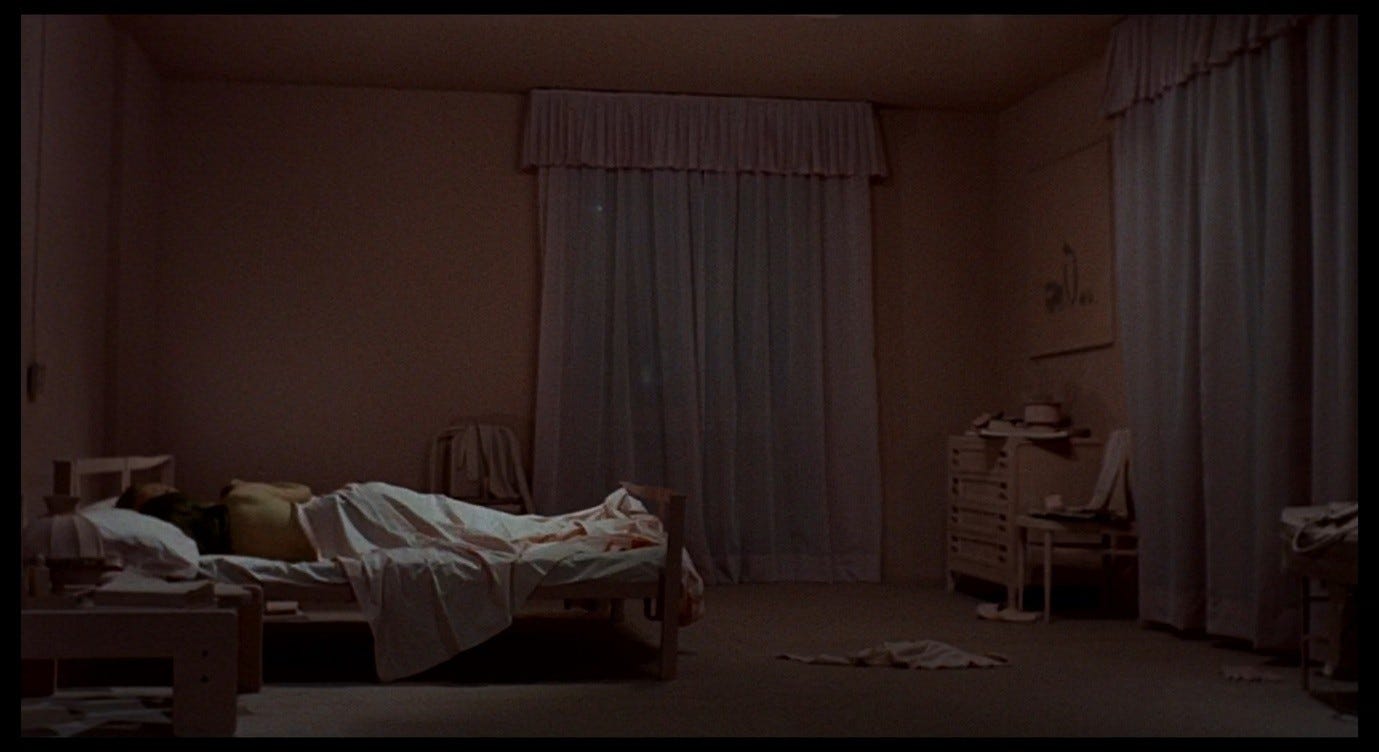

Rather than following Giuliana’s progress to the bed, as it did when she went to the window a minute earlier, the camera leaves Giuliana behind and moves towards the bed of its own accord. The walls of the room are now completely obscured. When we see the bed, it appears to be floating in darkness.

This gives the object a kind of emblematic quality. It is reminiscent of the dishevelled bed in the red room, exposed when the walls around it were torn away: in that scene, the image of the exposed bed made Giuliana feel ashamed because it revealed something about the tawdriness of that social encounter. The idyllic sense of communal affection and ‘free love’ was replaced by the sense of an exploitative quasi-orgy choreographed by Max, the predatory capitalist (see Part 19).

We might compare Giuliana’s disillusionment, in that moment, with Daria’s at the end of Zabriskie Point, staring in disgust at the tycoon’s desert mansion. Corrado’s bed also exists in a kind of void: not a literal desert, nor a set of red walls, but an intangible and infinite blackness. Like the bed in the red room, it is dishevelled, and here too this connotes a sexual encounter. To put it in melodramatic terms, it is as if the camera movement were saying, ‘behold, the bed of adultery.’ Giuliana’s line in the next scene, ‘I’ve even succeeded in becoming an unfaithful wife,’ wryly affirms her ‘insertion’ into this clichéd role.

These emblematic overtones increase the sense of unreality in this scene. The characters, their actions, and the setting they inhabit are all turning into tropes and concepts – social constructs rather than real, tangible things. This could be any room, any bed, any couple. Giuliana could be choosing to go to bed with Corrado, or (as I argued in Part 40) this could be read as a rape scene. Her feelings and her agency no longer matter, the images seem to say, because this is simply what happens: this is the climax we have been moving towards this whole time.

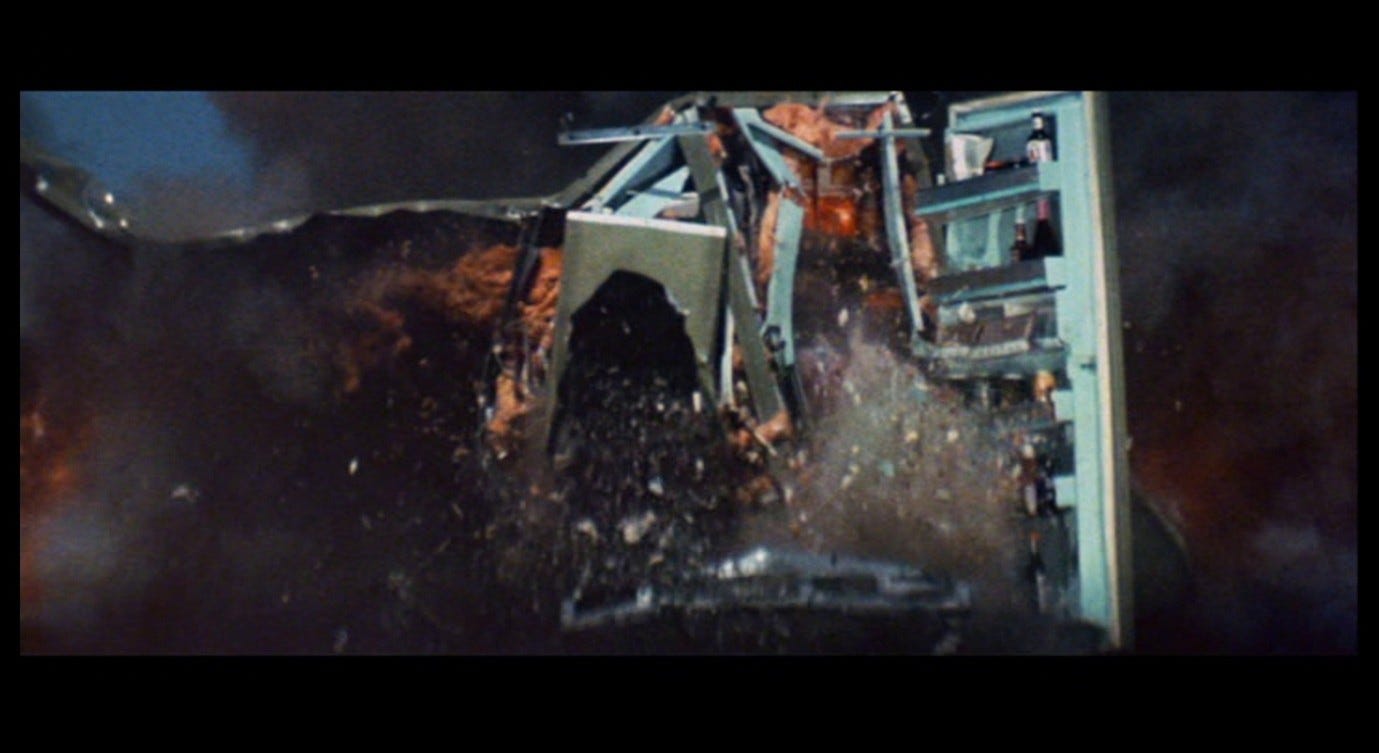

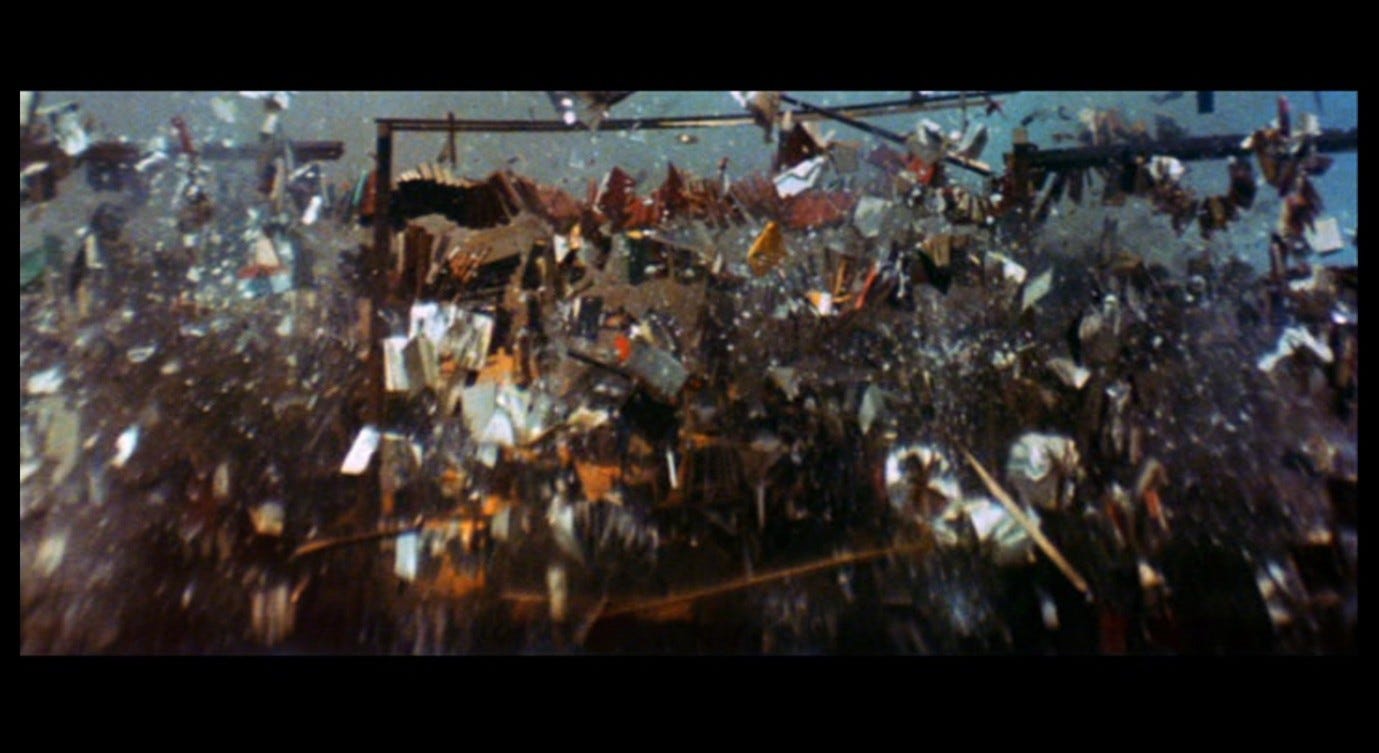

In Zabriskie Point, we do not know whether the mansion really blows up or whether this only happens in Daria’s mind, and those final explosions have a similarly emblematic feel. ‘Resolutely struggle against bourgeois individualism,’ says one of the students at the beginning, in a tone that clearly indicates he is quoting another (unnamed) source. He and the other students laugh at the way this subordination of the individual’s voice dovetails with the message of anti-individualism, and with their own collective response; the camera quickly pans away, blurring the students together before transitioning to the next scene.

In the final moments of the film, Daria-the-individual is subsumed by a counter-culture fantasy about the total annihilation of bourgeois individualism, itself ironically represented by countless inanimate objects rather than by actual people.

Angelo Restivo, commenting on the montage of explosions, challenges the idea that this is all taking place in Daria’s mind:

[T]he sequence is of such a protracted length, and of such stunning beauty, that it tends to undo its own articulation as fantasy, and to become something else. […] [W]e need to acknowledge – if only to later qualify or reject as overly simple – the idea that the ending suggests that all affective investments have been disconnected from action in the real world and relocated to the interiority of fantasy. While this provides us with a rather neat narrative trajectory, it seems incomplete. For one thing, fantasy is always intimately bound up with affect in ways that might be as likely as not able to fuel social relations and political engagement. To be sure, one does not imagine that Daria is driving off to join a terrorist cell at the end of the film. But then, having been mesmerised by the explosions, one doesn’t particularly imagine anything about Daria at film’s end; she has become irrelevant.1

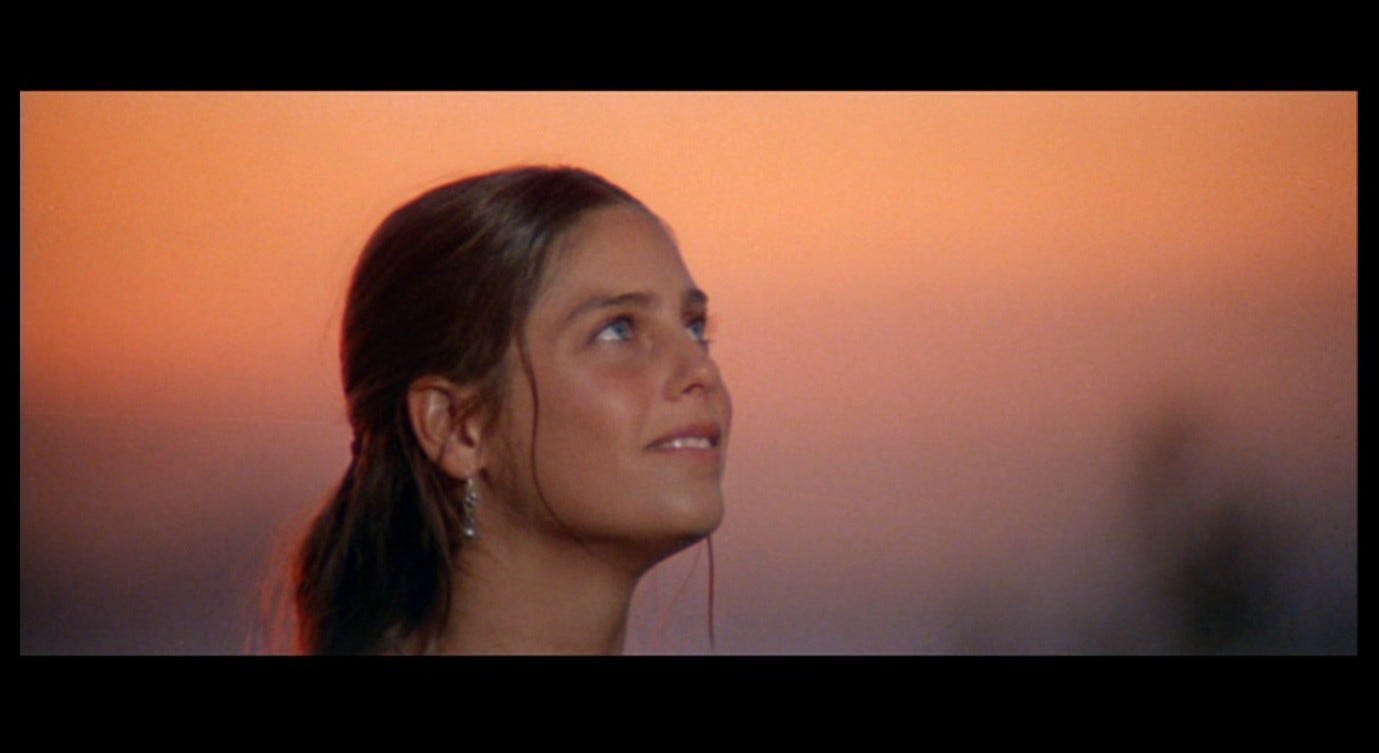

In the final image of the film, Daria is reduced to a clichéd image: the hero dissolving into the sunset.

As Restivo says, it seems irrelevant to wonder where she is going or what she will do next. We have not ‘snapped back’ to the real world after an unreal dream of blowing-everything-up. If anything, the slow-motion explosions have so completely taken over our reality for the last few minutes that the subsequent shot of Daria driving away seems less real. That, arguably, is what Daria’s final action means: not that she has decided to live in a fantasy, but that she recognises reality as a cliché and individualism as a trap, and opts out of them. She becomes, in Restivo’s terms, irrelevant, but by her own choice. Perhaps other kinds of social relations and political engagements will be opened up once Daria has driven into, and past, that hackneyed sunset.

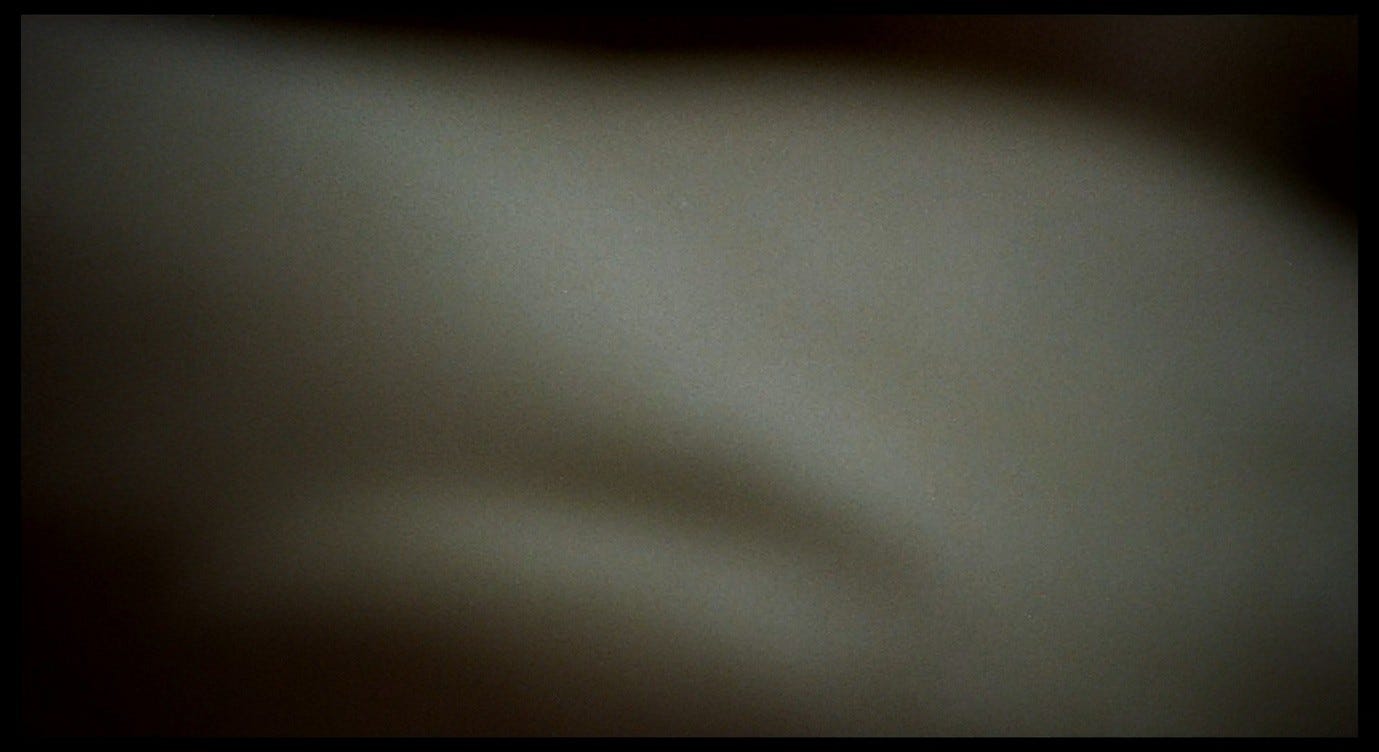

In Red Desert, the forces that engulf Giuliana’s individuality and agency are very different, although as in Zabriskie Point there is a kind of narrative determinism at work, requiring the film to culminate in something climactic. In the case of Red Desert, the pre-determined climax is the consummation of Giuliana’s and Corrado’s affair. The images we see, after that emblematic vision of the dishevelled bed, are of human bodies merging into each other. In extreme close-up, we see the sheets of the bed, then Giuliana’s back, then her red hair; her hair then transitions seamlessly into Corrado’s (a lighter shade of red); and before we know it, we are looking at his back instead; his body comes into focus as it covers Giuliana’s.

As in the earlier images of Giuliana’s tights wrinkling, which blurred the distinction between flesh and fabric, it is unclear where the boundaries between the bed, Giuliana, and Corrado begin and end.

At the climax of the factory-tour sequence near the start of the film, the entire image was consumed by a cloud of steam. Here it is consumed by de-individualised bodies. But whereas the steam receded and left no trace of itself behind, here the all-consuming bodies have a more lasting, totalising effect upon their environment. For some time, we have heard nothing but the sounds of the characters’ quiet breathing and grunting, mingled with the sounds of their bodies interacting with the fabrics on the bed. Now, the high-pitched electronic hum returns as we cut to a disturbing image. We see Corrado’s bedside table, the one with The Watcher on it, only now the table and all the objects are coated in pink, obscuring any individualising details.

Calvino’s novella could be any book now. The camera pans across the bed to show how this pink tone complements Giuliana’s skin. She is lying there with her face buried half in the pillow and half against Corrado; she turns her head so that her face is partially visible to us, and we see that she is half-asleep.

Then we cut to a wide shot of the room and see that everything has turned pink, even the black-and-white abstract painting and the black-framed picture of the trees.

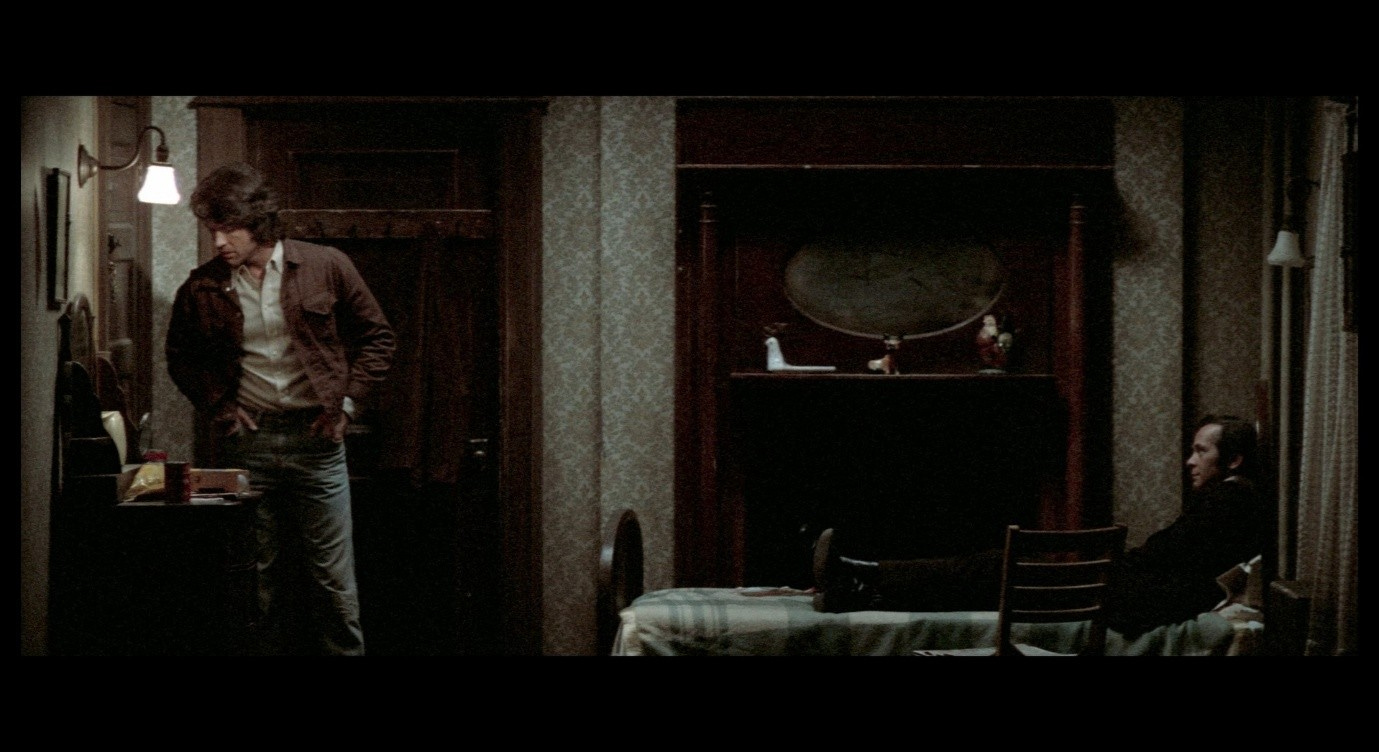

The white light that came through one window and the yellow light that came through the other are both gone now. The fact that there is no visible light-source within the image, coupled with the rather theatrical proscenium-arch composition, gives the image an artificial, studio-bound look. It resembles the wide shots of rooms in The Night of the Hunter, which in turn recalled those in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari; the images of Frady’s rented room in The Parallax View have a similar quality.

Each of these ‘whole-room’ images is conspicuously unreal in its own way. We feel that we are looking at a carefully constructed portrait, and that we are meant to be aware of the frame that surrounds it. In each case, the frame constitutes a malevolent trap for the characters, whether this trap is constituted by the evil preacher’s self-serving religious dogma, the madness that distorts the world of Caligari (or the evil psychiatrist who frames the protagonist as a madman), or the shadowy Parallax Corporation that has infiltrated Frady’s living-space, that will continue to control the spaces he inhabits from now on, and whose presence is felt in the black-void images that bookend that film.

Angela Dalle Vacche identifies a baroque sensibility in Red Desert’s ‘madness of vision,’ its ‘dazzling, disorienting, ecstatic surplus of images,’ which express emotion ‘through coloristic impressions,’ and she goes on to link this to ‘the stereotypical association of femininity with excess.’2 This again suggests a connection with the ending of Zabriskie Point, in which the film-maker’s excesses are attached to the mental state of the female protagonist. If Daria was expressing both her fury with bourgeois individualism and her intent to opt out of it, Giuliana is likewise expressing something about herself (and her motives for her subsequent actions) through the pink room. The image can indeed be read as an evocation of madness, a wildly over-the-top manifestation of Giuliana’s world-encompassing needs and desires, which are in turn a manifestation of Antonioni’s urge to convey some incommunicable feeling about reality. Like the three films cited in the previous paragraph, Red Desert is infused with a kind of freewheeling delight in the process of film-making that merges seamlessly into the sensations of terror it is trying to describe. Isn’t it wonderful, and at the same time awful (the film seems to say), that we can suddenly turn this whole room pink, or (in Zabriskie Point) that we can blow everything up, over and over again?

The film-studio artifice of Red Desert’s pink-room shot is complemented by another kind of artifice. The pinkness has the appearance of a fine powder or residue, like other residues and side-effects of industrial processes seen throughout the film. The room has been spray-painted and colour-coded, like any other coded object in the industrial landscape.

It makes me think of the artificiality of the pink flowers outside Mario’s apartment complex (see Part 16). In this world, colours are deliberately applied to objects, or to whole environments, in order to define their identity. Certain rooms or pipes in Ugo’s factory are blue or green or red to signify their function. Certain gases are coloured yellow to indicate toxicity. The blackness of the slag-heap, and of the trees adjacent to it, mark that area as a place of refuse, a marginal landfill site where nobody goes, unless (like Giuliana) they feel like a marginal leftover themselves.

In the pink-beach fantasy, Giuliana-as-narrator remarked that ‘the colours of nature were so beautiful.’ In that natural setting there was no sign of the ‘singleness of purpose’ that motivates the discrete colour-coding of the factories, and that Hermann Broch (in The Sleepwalkers) figured as the antithesis of beauty. Instead of discrete, demarcated colours, we found tones fading seamlessly into each other: the blues of the sky and sea, the pinks of the sand, rocks, and human flesh.

However, the bedtime story was not simply an idyllic fantasy of a place where Giuliana wished to live. ‘There are few oases left’ – even that oasis seemed to dissolve into a kind of nightmare as the boundary-disrupting mysteries of the visiting ship and the disembodied voice intruded upon the scene. It was specifically the impression that ‘everything sang...everything [tutti cantavi...tutti]’ that seemed to prompt the final dissolution of the story and the snap back to reality. Something about those rocks that so closely resembled human bodies, and that voice that seemed to emerge from all of them at once, created an effect that was more disturbing than comforting.

In her final outburst in Corrado’s hotel room, Giuliana’s list of things that terrify her culminates in ‘colours, people, everything [tutto].’ The girl in the bedtime story was frightened of people, which is why she retreated to that isolated cove, but as the story went on those people seemed to pervade her place of refuge in ways that marked them as both absent and present. The mysterious ship was un-manned, yet was clearly being directed by some form of conscious intention. There were no people in the cove, but the girl suddenly realised how much the rocks resembled people, and the singing voice seemed to invest all the non-human features of the environment with an aspect of humanity. That fantasy ended with a camera movement that showed everything out of focus and made the blue of the sea merge with the pink of the rocks, much like the panning shot that shows bedsheets and bodies merging in Corrado’s hotel room. These hazy moving images seem to illustrate Giuliana’s cry of despair: colours, people, everything!

The spectacle of the pink-coloured room serves as a kind of answer to the questions, ‘What is Giuliana afraid of?’ and ‘What happens to Giuliana?’ Earlier in this scene, she said that she wanted all her loved ones around her like a wall, and now the walls of this room – and indeed all the surfaces – are the same colour as Corrado’s flesh and hers. On the SAROM rig, she told Corrado that if she travelled abroad she would want to take literally everything with her, everything she had sottomano – even the ashtrays. (We may have noticed the ashtray in the foyer of this hotel, partaking of the uniform whiteness of that setting.)

She considers these things not only ‘beneath her hand,’ but part of her hand, things that she touches and bonds with permanently. Corrado, like these things, has become part of her life, part of her self. The pink hotel room embodies this idea, collapsing the difference between people and things. In one sense, Giuliana has been granted her wish, and indeed there is an element of calm and relief in the image of the pink room. Looking at this shot in isolation, with the sound off, you might think that Giuliana seems peaceful and contented as she lies with Corrado. The pervasive pink colouring could even be seen as an antidote to the ominous multi-coloured stain that was previously seen spreading over the walls and ceiling; if that was an illness or infection, the pink colouring has cured it. For a moment, we might think that this sex act has assuaged Giuliana’s anxieties, as if all she needed was a good orgasm to make her feel more connected to the world.

But the effect of the pink-room image is far more disturbing than this interpretation would suggest. Indeed, insofar as there is an ‘element of calm and relief’ here, this ironically increases the sense of unease. Like the greyed-out fruit and the greyed-out empty street in the Via Alighieri – but more so – the sudden universal pink has an uncanny effect. It is like the moment in In the Mouth of Madness when Sutter Cane says to John Trent, ‘Did I ever tell you my favourite colour was blue?’, and Trent wakes up to find the entire world tinted blue. After taking a moment to register this, he screams wildly.

We only see Giuliana and Corrado in that moment when neither of them has yet had a chance to notice the transformation. Their state of repose seems at odds with the supernatural change in their environment, as if the spider-monster from Enemy had materialised but no one had seen it.

In Christine Henderson’s description of the pink-room scene, the pinkness is a coating of denial intended to protect Giuliana against reality:

[T]he two [characters] become indistinguishable, and abstract angles of the bodies take on the appearance of the pink, speckled rocks of her fantasy. All goes quiet and the faint sound of waves becomes barely audible. […] [T]here is a still shot of the room awash in pink tones as though everything were coated in a thin layer of sand. However, this bliss is inevitably short lived. Giuliana’s intuition that sexual union with Corrado will not save her has been confirmed. The real continues to intervene, to violently burst through her screens.3

As we saw in Part 40, this emphasis on Giuliana’s agency can lead to problems: it is an understatement to say that she has an ‘intuition that sexual union with Corrado will not save her,’ because this frames the sex scene as something she has sought out against her better judgement. She does not, I think, come to Corrado for sex, and her ‘stop’ gestures earlier in the scene reflect more than a mere intuition. The pinkness, in Henderson’s reading, represents a kind of bliss, but a bliss as unreal as that of the pink-beach fantasy: it is something Giuliana needs to work through and transcend, towards a more responsible engagement with reality. But I would argue that this pink layer is part of ‘the real’ – it is a layer of reality – and that it signifies more than transient bliss, just as the pink-beach fantasy signified more than a dream of prelapsarian innocence and self-containment. Henderson hears only the soothing noises, not the disturbing ones, on the soundtrack, and by the same token she does not see the sinister undertone of the pink colouring. Then again, I do not hear the sound of waves, only the friction of bodies against bedsheets followed by an aggravating white noise underneath the electronic chord, so I may be missing something in this sequence.

Philip Novak provides a useful corrective to my earlier suggestion that the pinkness is an ‘antidote’ to the nightmare-colours that had appeared on the walls and ceiling:

[T]he hotel room they are in and everything in it has been washed a pale, sickly pink, as if the bright pink stain Giuliana had hallucinated just prior to the sex (a vision presented clearly as an hallucination) had somehow leached into the whole of the world.4

Now pink is coded in terms of a washed-out, sickly pallor, a homogenised dilution of the purple-yellow stains, or a leaching-out process whereby those stains spread themselves thinly across every visible surface. The pinkness and the stains are manifestations both of Giuliana’s internal state and of the external forces that impose themselves on her. Her wish to be bonded with everything/everyone and her fear of being infected by everything/everyone are both fulfilled at the same time. When she drew the purple-yellow-black vortex on Valerio’s chalkboard, Giuliana was both expressing herself and drawing the thing she was afraid of; the same goes for the story she then told of the girl on the pink beach; and the same goes for her ‘painting’ of the hotel room. The thing that is inside her terrifies her, not least in its capacity to change her environment, or her perception of that environment. Novak seems to distinguish the bright wall-stains (which he says were clearly hallucinations) from the pervasive pinkness, which has ‘leached out’ of the hallucinations into the real world. I think both colourations partake of the same ambiguity: just because Corrado could not see the stain Giuliana pointed to on the wall does not mean that it was a hallucination. It might have been Giuliana’s way of seeing a reality that he could not, and indeed it might have been her way of seeing him.

For Paul Coates, the pinkness is a sort of critical commentary on Corrado:

[A]fter her unsatisfactory love-making with Corrado […] the final dominance of pink wittily and ironically shows their intercourse as not a triumph of the male who has longed to possess her physically, but one of the most stereotypically ‘feminine’ of colours. It is as if Corrado has not so much succeeded in seducing Giuliana as seen his space flooded by her femininity, been unmanned.5

In this light, the pink flowers outside Mario’s apartment might also be read as an emblem of femininity, haunting and threatening Corrado. But again, the reading of the sex scene is crucial here: Coates argues that the love-making has been ‘unsatisfactory,’ and this seems to be part of the un-manning of Corrado, a rebuke to his attempt at masculine dominance. He longs to possess Giuliana and to ‘succeed in seducing her,’ but instead she bests him by flooding his space with femininity. It is hard to square this reading with the specific interactions we saw between Giuliana and Corrado once he started to undress her, nor do I see any evidence of unsatisfactory love-making in the tableau of them lying naked in bed together. The images of the two bodies writhing, connected as they are to the earlier images of the flesh-like rocks in the cove, associate pinkness not with femininity but with nudity, and with sexuality. This pink-flooded room does not spell Corrado’s emasculation, but the outcome of his ‘seduction’ (or rape) of Giuliana. ‘This is what you have done, to me and to the world,’ she is saying; the image is, in a way, her depiction of how he views this scene.

Giuliana is plagued not only by internal but also by external forces. The pervasive, menacing colours embody something that is in the factories, streets, and people that surround her. For example, we might associate them with the oppressive patriarchal norms that shape ‘romantic’ narratives, that have shaped Corrado’s sense of his relation with Giuliana, and that have forcibly placed her in this position. Antonioni, the director who laboriously spray-paints his sets and locations, makes the film complicit in trapping Giuliana like this. But these hyper-manipulated images of re-painted sets and locations are so artificial that they make us aware of the controlling hand that created them. In other words, the room is only pink because someone painted it; Giuliana is only here because someone put her here; and the film will now snap back to ‘Giuliana herself,’ seen as distinct from these controlling forces, attempting (in the last few scenes of the film) to reach a conclusion on her own terms.

Years later, Antonioni was drawn to the colour manipulations made possible by video effects, and he deployed these in his made-for-TV film, The Oberwald Mystery. At one point, the queen looks out of a window at the trees outside, which appear to be a normal, slightly muted shade of green. As she opens the window, a more vivid green infuses the trees and then floods the interior of the queen’s bedroom.

It is one of the simpler colour effects in the film, evoking the impact of fresh air and the smell of the pines on the queen’s inner emotional state and her sense of the place she is in. As grey and depressing as the castle is most of the time, it can be transformed in a moment by a sense of connection to the green world. By the same token, another moment can dispel this feeling completely.

While the queen reflects on the brevity and changeability of the weather, we see the moon turning yellow, then blue.

The moon is a traditional image of changeability, and in this film colour itself is associated with change, because it can be altered and manipulated so easily. Throughout Oberwald, colours also serve the function of exposing hidden truths, serving Antonioni’s larger project of revealing images beneath images:

We know that under the revealed image there is another one which is more faithful to reality, and under this one there is yet another, and again another under this last one, down to the true image of that absolute, mysterious reality that nobody will ever see. Or perhaps, down to the decomposition of every image, of every reality.6

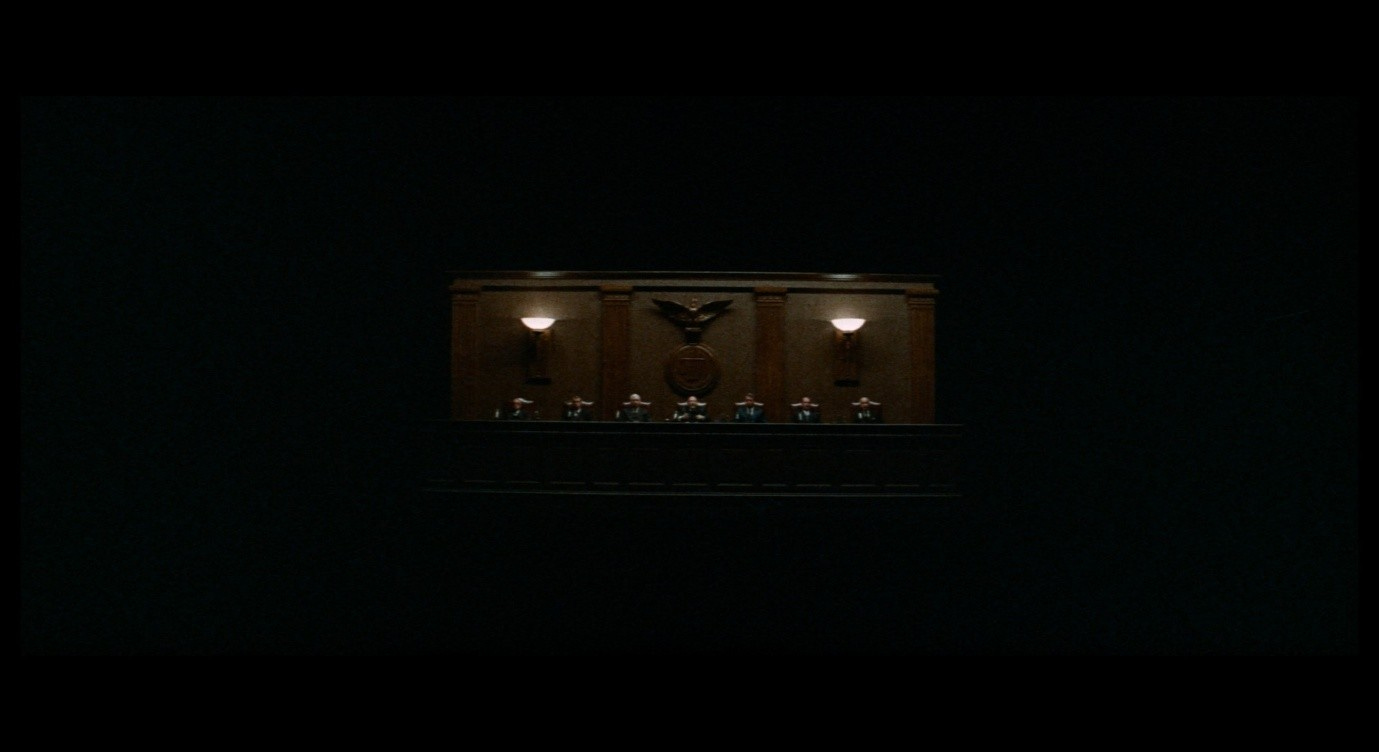

In Oberwald, this theme is explored by imposing colours onto the filmed image in order to uncover something that would otherwise be invisible. Whenever the villain, Count Föhn, appears, he is surrounded by a blue/purple mist, which sometimes extends over whole rooms and infects other characters.

This might suggest that this colour stands for evil or duplicity, and for Seymour Chatman this is the film’s fatal flaw:

Settling for simple heroes and villains can only banalize the use of colors to characterize them. […] The film uses uncharacteristic symbolism, representing a thought or moral trait with a single color. Since Föhn is evil, and lavender suggests evil, he is colored lavender. One remembers with nostalgia […] the post-coital rose of Corrado’s hotel room.7

Chatman is referring to the ambiguity of that post-coital rose, which he feels is missing from Oberwald, but he does not explain why lavender would ‘suggest evil.’ Paul Coates draws a similarly unfavourable comparison between the two films:

[T]he motif of the world’s variable perception, correlated so powerfully with mutations of colour in [Red Desert] […] vanishes from The Oberwald Mystery. Instead of the blending of ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ viewpoints in the ‘free indirect subjectivity’ whose centrality to Red Desert was noted first by Pasolini, one has a simple alternation between them.8

According to this reading, if Red Desert were made like Oberwald, we would see the hotel room turn pink and then see the pink fade away again. We would understand that this brief transformation represented Giuliana’s subjective point of view, and that there was no ‘leaching’ between this and the more objective viewpoint.

However, Oberwald becomes more complex when we look at its use of blue as a tinting effect for night-time scenes, flashbacks, and scenes associated with the act of remembering. Blue, in this film, always evokes a kind of darkness: the literal darkness of night, the obscurity of a partially faded memory, or the metaphorical obscurity of Föhn’s deceptions and hypocrisies. Late in the film, when the queen and her lover are together, the room turns light-blue around them: Föhn’s blue is more purple-ish, more like the sickly bruises that appear on the walls and ceiling in Red Desert; this blue is the one associated with memories, reveries, and dreams.

This is the plane of existence on which the queen and Sebastian operate, one that is as tenuous as a memory and appears to be fading before our eyes. Indeed, it is related to Föhn’s blue because it represents a kind of lie or delusion. Memories mislead us and so do fantasies of transcendent love. Föhn is indeed a simplistic villain – written as such by Jean Cocteau in the play Oberwald is based on – but the film is less interested in making us boo and hiss him than in making us see him on a blurry continuum with the supposed heroes. The queen sits in a chair, day-dreaming of love, and she gradually dissolves in the blue light that surrounds her.

At the end, the dead lovers are framed as a lifeless component in a still image whose artificial colouring has drained away, like the fading-photograph effect in the last shot of The House of Mirth.

‘With the departure of the lovers’ idealistic energies, life itself becomes moribund,’ says Paul Coates of The Oberwald Mystery.9 But I think those idealistic energies were themselves part of the ‘moribund’ quality with which ‘life itself’ is always imbued in Antonioni films. They were a blue haze, a video effect applied artificially, a hypocrisy of the kind we all engage in whenever we try to connect with each other. Colour is not only changeable, it is fragile: it degrades into a colourless state over time. The characters in Oberwald, like those in The House of Mirth, inhabit a world of surfaces, conventions, and deceptive appearances. The love-relationship is part of that same world, as transient and impermanent as all the other surfaces and the colours that adorn them.

Murray Pomerance reads Oberwald as a meditation on photography’s ability to recover (and uncover) lost phantoms:

Cinema’s continual unfolding means that the past is continually reappearing as the present and that every present glimpse is also a reexperience of the past. […] [T]he young man is a kind of ghost figure representing the King […] [and] we may also imagine that [the queen], too, is a ghost of what was, and in much the same way. Who, indeed, is not?10

He later calls the film an evocation of rhythms ‘in which the past reverberates now, and in which this moment will last and reverberate tomorrow.’11 But the ‘reappearance’ of the king is merely a reiteration of his death, both because Sebastian is not in fact the king and because he also dies. To connect with the past is to be immersed in a blue vapour: it entails reckoning with the irretrievable decay of those past things and people, and of everything in the present including oneself. This moment will not last and reverberate tomorrow, it will dissipate just as all previous moments have.

There is, in short, plenty of justification for Giuliana’s fear of colours: not only can they trap you in a place, a mood, or a relationship that you did not want to be in, but in so doing they also remind you that you are a contingent fragment of reality, created against your will and doomed to be annihilated in the same way.

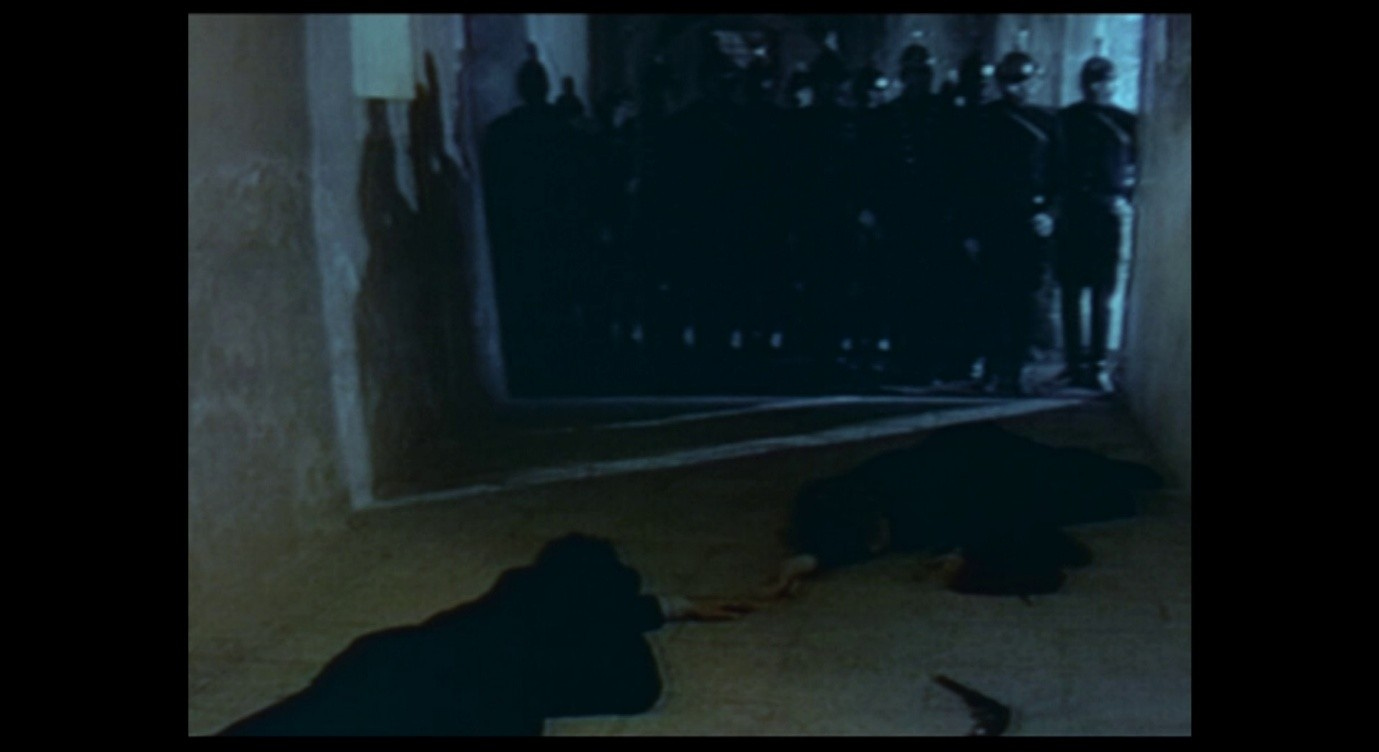

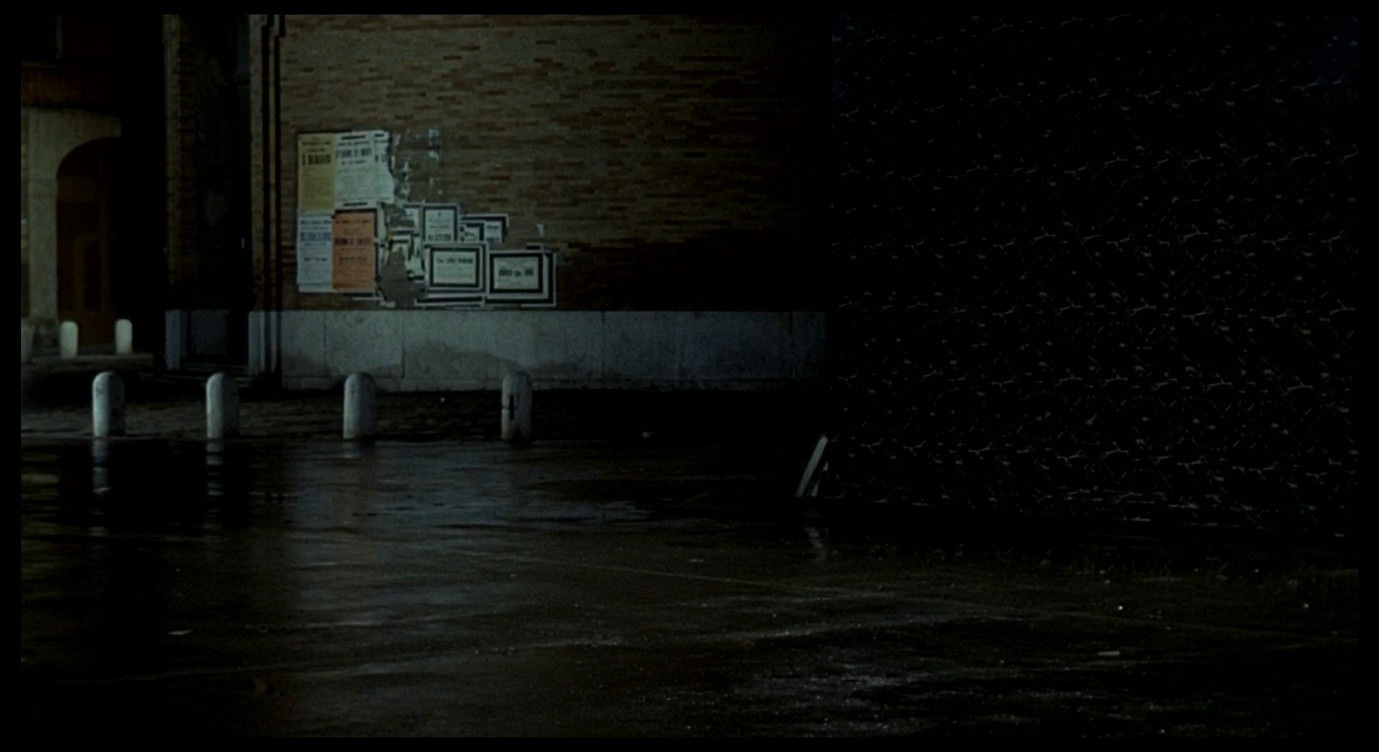

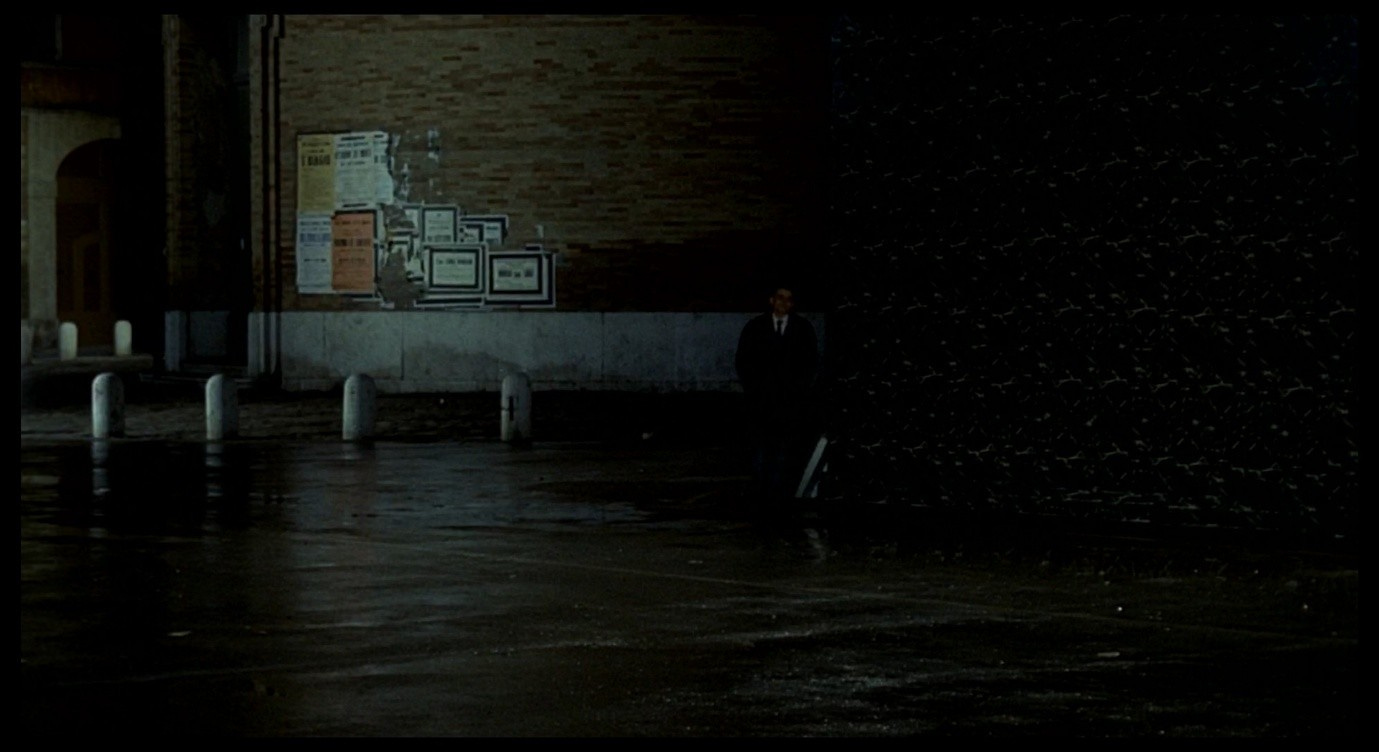

The disturbing tone of Red Desert’s pink-room image is thrown into relief by the next shot, when we cut to the exterior of the hotel.

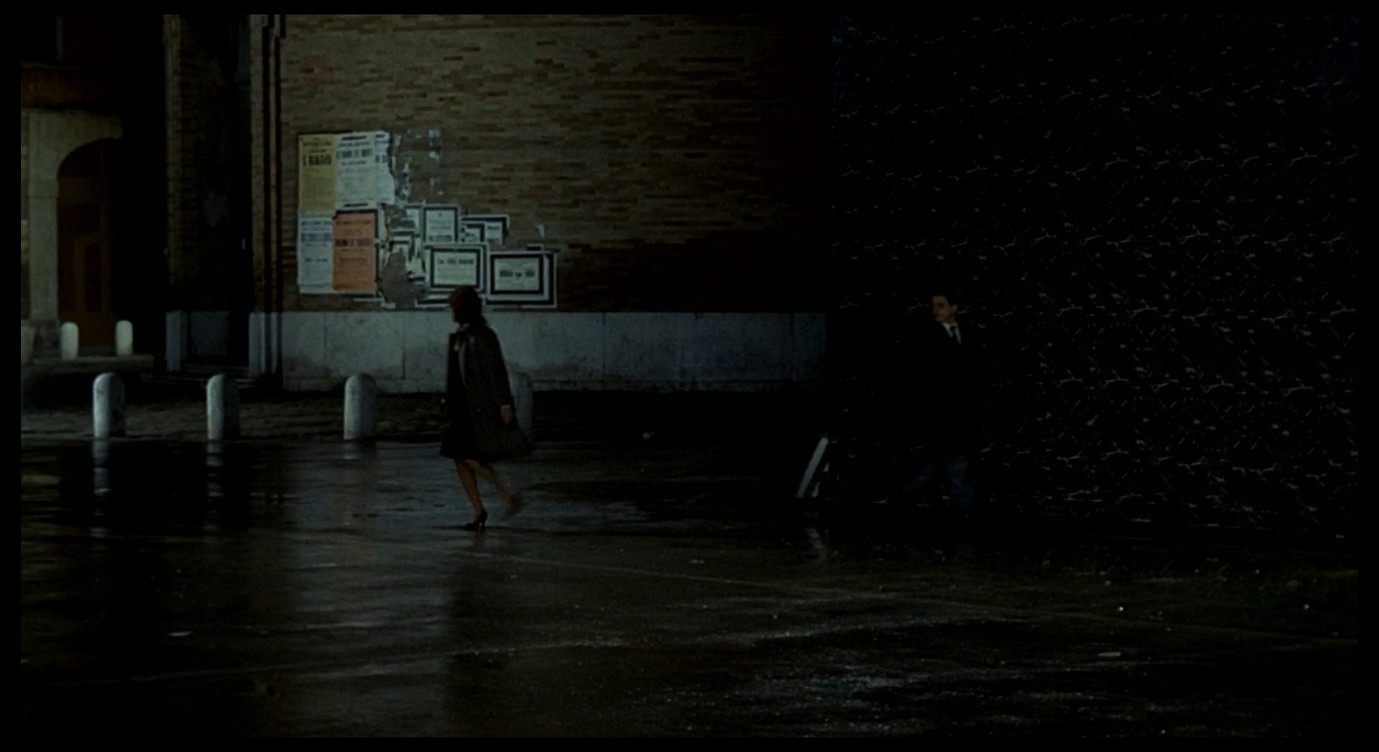

This scene was clearly filmed on location and the location appears to be un-manipulated. We go from a highly artificial image to documentary realism, with street sounds (a car engine in the distance) rudely interrupting the sinister hum from before. A man emerges from behind a building, and after a moment we realise that we do not recognise him – this is a subtle misdirection reminiscent of the ending of L’eclisse, except here the stranger is quickly followed by the expected protagonists. Giuliana dashes out from behind the stranger, looking around in confusion before running off down the street; then Corrado (still putting his jacket on) follows her.

We can see the death notices on a wall in the background, reminding us of the morbid spectacle offered by the hotel-room window a few minutes earlier.

The agitation of the exterior shot, and the impression that Giuliana is running away from Corrado, undercut any sense of tranquillity created by the pink-room image. By skipping over the transitional moment when Giuliana (presumably) becomes anxious, gets dressed, and hurries from the hotel room, the sequence insists on a kind of direct continuity between lying-in-bed and running-away. Earlier, the cut from the foyer to the third floor made Corrado’s reception of Giuliana seem disturbingly immediate, as if all she had to do was begin ascending the stairs to find herself instantly being welcomed into his room (see Part 36). Now, at the end of the sequence, the cut from interior to exterior makes it feel like Giuliana is leaving the building within a moment of lying in Corrado’s bed. We were seeing the pink room from her perspective: dissociated from her own experience, she looked at herself from the outside, lying passively next to Corrado, one anonymous pink object among many others. Horrified by the spectacle of her body-snatched self, she instantly ran outside, followed by an almost-fully-clothed Corrado who is also uncannily distinct from the naked doppelganger we were just looking at. The cut to the outside world is almost comical in its rejection of the scene before. Giuliana does not like the nude scene she finds herself in, so she simply and instantaneously opts out of it.

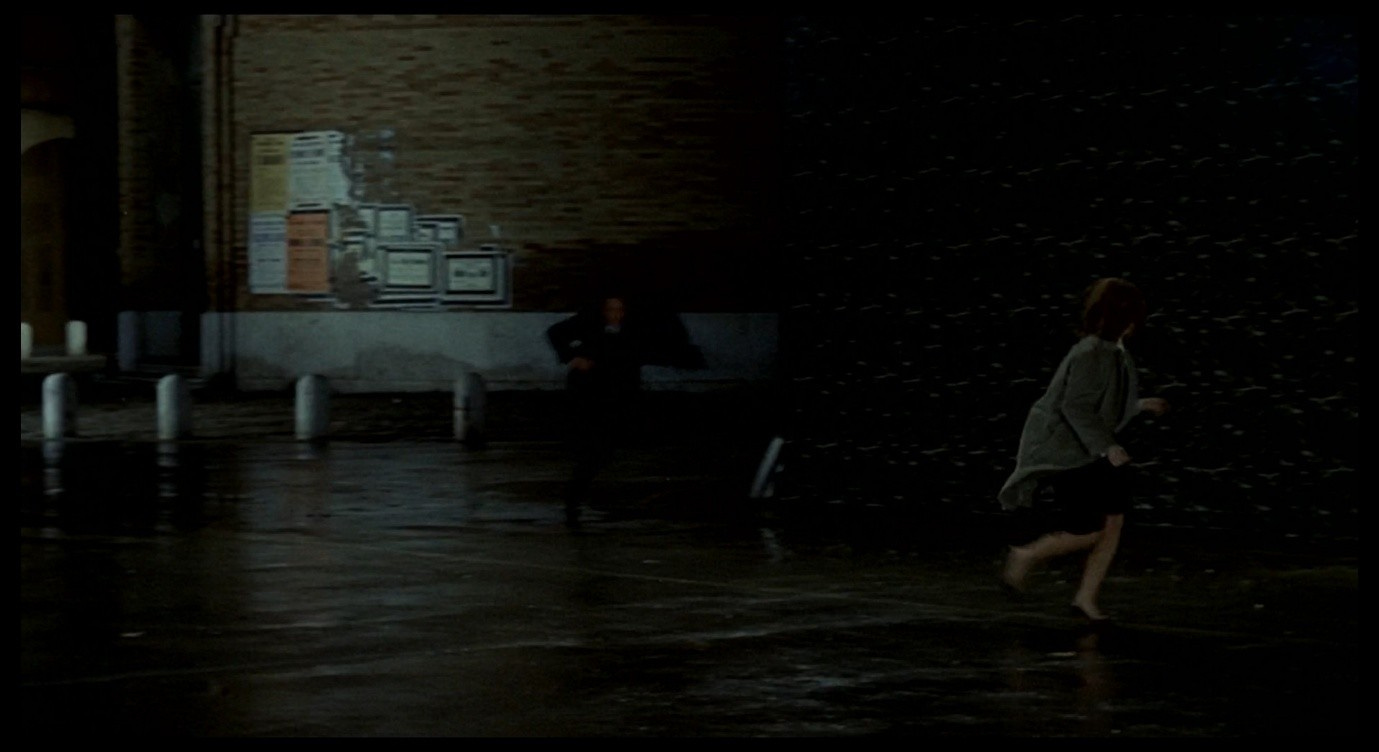

This impression that we are now ‘out of the film’ is compounded in the disorienting long-lens shot where Giuliana runs down the street, Corrado catches up with her, and inaudible dialogue passes between them. The film crew cannot quite keep up with or register what is happening. We can see that Giuliana is trying to put Corrado off, but we are too far away to hear what she says to him. Like Pavese’s Rosetta (in Among Women Only), she seems to want to be left alone – by us as well as by Corrado. As she runs down the street, she passes yellow- and red-lit windows and a set of multi-coloured lights: these are more naturalistic real-world manifestations of vivid colour than those we saw in the hotel room. But on the heels of those colours, these still carry a residue of angst, like glaring remnants of the bad-dream dimension spilling over into waking life.

Giuliana is re-asserting her own agency here, but she still lives among the colours that terrify her, and – despite her embarrassed hesitation as the strange man walks past them – she still has to give in to one more of Corrado’s desires, as it is clearly too late to walk home. She stiffly accepts his offer of a lift.

He will now drive her to her empty shop in the Via Alighieri, where (on her own ground and her own terms) Giuliana will end their relationship.

Next: Part 42, Two failed projects.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Restivo, Angelo, ‘Revisiting Zabriskie Point’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 82-97; p. 95

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), pp. 51-52

Henderson, Christine, ‘The Trials of Individuation in Late Modernity: Exploring Subject Formation in Antonioni’s Red Desert’, Film-Philosophy 15 (2011), pp. 161-178; p. 175

Novak, Philip, Interpretation and Film Studies (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p. 77

Coates, Paul, ‘On the Dialectics of Filmic Colors (in general) and Red (in particular): Three Colors: Red, Red Desert, Cries and Whispers, and The Double Life of Véronique’, Film Criticism 32.3 (2008), pp. 2-23; p. 14

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Preface to six films’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 57-70; p. 63. Cooper translates the last sentence as, ‘Or perhaps, not until the decomposition of every image, of every reality.’ But the sentence uses the same ‘fino a’ construction as the previous one, which refers to the unveiling of successive layers of images: ‘Fino alla vera imagine’ means ‘Down to the true image,’ and then I think ‘fino alla scomposizione’ means ‘down to the decomposition.’ In other words, Antonioni is not imagining a time when someone will see that ‘true image,’ but rather imagining that peeling back these layers would not even reveal the truth but cause all images and realities to disintegrate. Italian text from Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), p. xiv.

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 211

Coates, Paul, Cinema and Colour: the Saturated Image (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 137

Coates, Paul, Cinema and Colour: the Saturated Image (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 137

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp. 150-151

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 151