Everything That Happens in Red Desert (35)

The ship and the song

This post contains a spoiler for Le bonheur.

Two mysteries intrude upon and compromise Giuliana’s fantasy of the pink beach. It is the mysteriousness, as such, of the visiting ship that is figured as disturbing: the ship is said to create a ‘splendid effect’ from far away, but ‘close up instead [invece] it became mysterious,’ the word invece signalling that the mystery somehow contradicts the splendour. Likewise, the singing voice is figured as ‘one mystery too many.’ So far, the cove’s status as a paradisal idyll has been tied to its naturalness – that is, to the natura that has such beautiful colours and creates no excess noise – but this naturalness was dependent on an absence of mystery. In the natural world, this story seems to say, things simply are as they are; there are naturally occurring sounds and colours, there is nothing strange or out of place. The girl has escaped from the perverse aspects of her world – the frightening adults and the children who behave, against their nature, like adults – but now she is faced with even more inexplicable phenomena.

The ship, besides seeming archaic, is also said to be a ‘real ship [vero veliero],’ a semi-mythical exploratory vessel from the past that has ‘traversed the seas and storms of the whole world, and even – who knows? – beyond the world.’ The word vero invokes the concept of authenticity, as if to say that this ship is a relic of the days when ‘ships were real ships.’ Confusingly, however, it is the very authenticity of the ship, its quintessential ship-ness, that causes it to transgress the limits of nature: only a vero veliero like this could have travelled so far and passed beyond the limits of this world. The poxy little ships the girl is used to seeing could never accomplish such a journey, nor could the people who sail them, hence the absence of people on this mysterious ship. The people of today could not sail such a vessel. Just as the cove represents a conflicted prelapsarian fantasy about the lost natural world, so the ship represents another kind of nostalgia (equally conflicted) for another kind of loss.

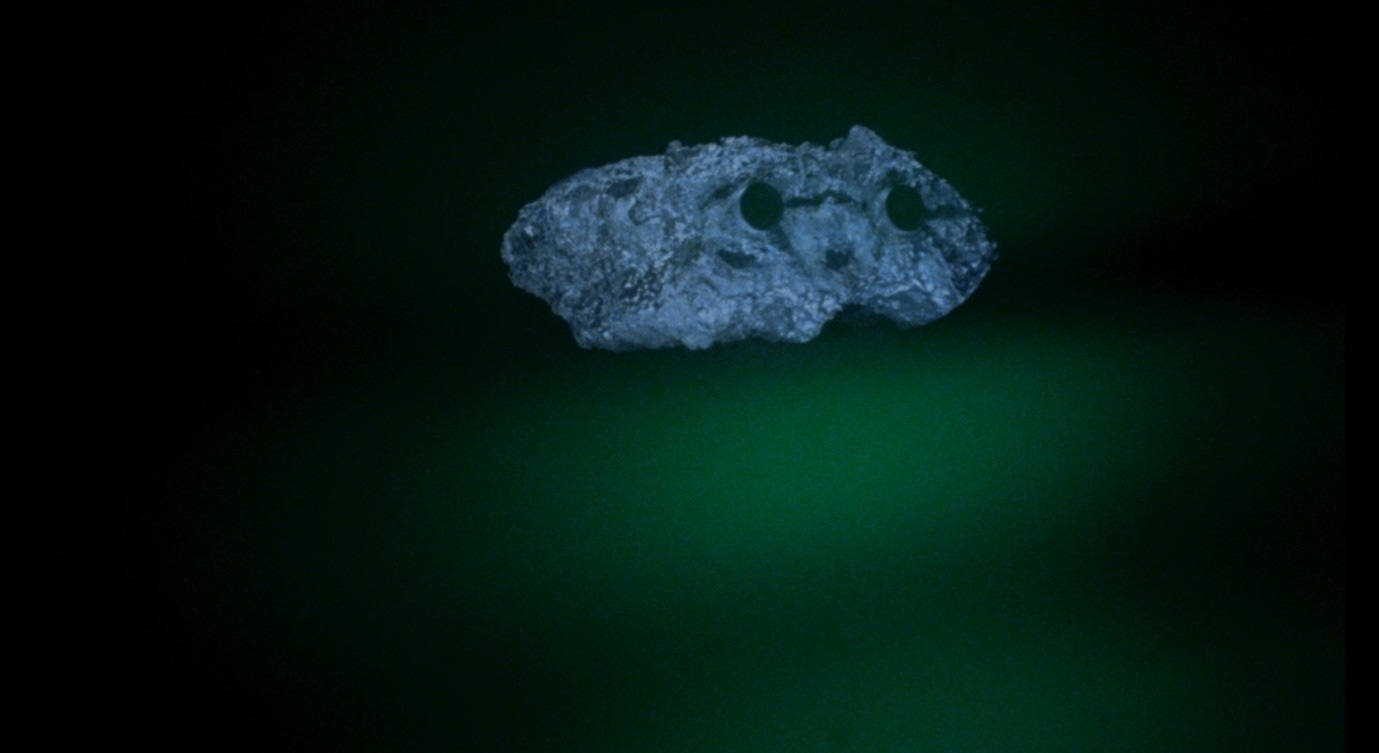

The vessel appears for a brief moment, but it is strange, uninhabited, and inaccessible, and it leaves almost immediately, glancing into our world only to reject it. When the ship first arrives, it travels along the horizon, at the edge of the planet.

When we last see it, the composition is almost exactly the same – the camera has panned slightly to the right – but the ship is now travelling in the opposite direction, off the planet (so to speak).

Giuliana comments that it leaves ‘silently, as it had arrived,’ underlining the parallel between the two images and adding to the sense that this ship fades into and out of existence as it moves over the horizon. If the ship is something we have lost, the images of its appearance and disappearance serve to affirm this loss: here is something that can no longer exist in this world, on this planet. The effect is similar to the appearance of the greyed-out Via Alighieri or the polluted natural spaces earlier in the film, except that now the emphasis falls not on what we have discarded and left behind, but on something that has discarded us and left us behind.

The way the ship moves across the horizon recalls the ship Giuliana saw earlier in the film, apparently sailing through the woods, blurring the boundaries between the land, the road, and the river.

In the fantasy cove, boundaries are blurred in similar ways: because the sea is transparent we can see the land beneath it, and indeed the sea appears to transform into the land – into the beaches and the rocks – by imperceptible stages.

Angelo Restivo argues that the ship

marks the point where meaning fails in the visual field, where meaning is ‘left unrevealed.’ It stands in for some unspecified trauma (perhaps the mysterious fate of its sailors); and as such, it ties together all the other many images of ships in the film.1

This association of the ship with failed or unrevealed meaning, and with a similarly unrevealed trauma, opens up a way of reading an earlier moment that precedes (and perhaps, in some sense, triggers) the ship’s arrival. When the girl reclines on the beach and sits up to look at the ocean, we see a ground-level view of the lapping surf, first from a distance and then from close up.

These images show layers of colour transitioning into each other, from the dark blue sky to the light blue sea to the grey/brown surf (whose rippling texture resembles paint on a canvas) to the pink/brown sand. In the first image, land stretches thinly and obscurely across the horizon. The world populated by humans appears tiny, dwarfed by the sky above and the sea and sand below.

The second image focuses entirely on the transition from the sea to the beach, and on the disruptive force of the surf breaking as it washes rhythmically over the sand.

Giuliana is, at times, drawn to a version of reality in which all things blur into each other, and in her story she imagines being able to spend all her time immersed in these blurred boundaries, gazing at the sky-sea-land or moving freely between them. Such imagery is also used throughout Daughters of the Dust to suggest the continuity between past, present, and future. It is particularly striking in one of the photograph-taking scenes, when Mr Snead and a few of the Peazant men venture onto the beach just after the tide has gone out. In perhaps the most beautiful series of shots in the film, we see land, sea, and sky become truly indistinguishable from each other, partly thanks to the Antonioni-esque greyness of the weather on that day of shooting.

The transitions through which the Peazant family is going are, at times, a cause for anxiety and tension, but Julie Dash uses imagery like this to emphasise an overall tone of optimism. In this moment, this space seems infinitely traversable, the people in it infinitely free, the elements around them (sky, sea, land) in perfect harmony, and this elemental harmony lurks benevolently behind even the most painful scenes in the film.

The elemental forces in Red Desert are less benevolent. For Giuliana, as we have seen, the idyllic vision of unbounded love and connectedness (husband-son-job-dog) can itself blur into a nightmare (see Part 17). The splendid other-worldly ship becomes a little too other-worldly, its association with boundaries – with the liminal spaces between reality and whatever lies beyond – indicative of a kind of loss, of things phasing into oblivion rather than being joined together. Following the ship’s abortive visit to the bay, the pink beach itself will be visited by a phenomenon that is splendid-verging-on-frightening, and that lends a more sinister cast to those porous layers of sky-sea-land.

In Part 2, I noted the credit in the title sequence thanking Piero Tizzoni ‘for the use of his pink beach [spiaggia rosa],’ and the relationship between the phrase spiaggia rosa and deserto rosso. At the beginning of her story, Giuliana refers to the ‘pink sand [sabbia rosa]’ in this cove. When the singing voice appears, she comments that ‘the beach was deserted as always [la spiaggia era deserta come sempre],’ alluding to the film’s title with the word deserta. Antonioni’s explanation of the title is worth citing again:

‘Desert’ perhaps because there are few oases left; ‘red’ because it’s blood. The living, bleeding desert, full of the flesh of men.2

The cove in Giuliana’s story is a kind of oasis, in part because it is deserta, but also because it is suffused with natural colours, especially the rosa that makes the sand and the rocks resemble human flesh. The spiaggia rosa is in some ways the antithesis or mirror-image of the deserto rosso. The pink beach is ‘full of flesh and blood’ in the sense that it seems like a living entity, whereas the red desert is ‘full of flesh and blood’ because it is a monument to death and destruction; the former is blissfully deserted and uncompromised, the latter has been made into a desert by invasive and exploitative forces.

However, these two spaces – the beach and the desert – are not simply antithetical to each other. Those painterly images of sky-sea-sand show these elements merging into each other, thereby calling into question the distinctions between them. In the long shot (which includes the sky), the waves splash against the shore in a soothing natural rhythm, in contrast to the agitated ‘ah-ah-ah’ of the flames spurting from the flare-stack in the opening scene (see Part 5).

But the cut to the second image, showing only the point of contact between water and land (without the sky), is timed to elide the pause between the waves, so that one ‘splash’ noise occurs too soon after the previous one.

For a brief, uncanny moment, these natural sounds feel unnatural, as if the tide itself were controlled by a mechanical process that can increase the frequency and regularity of the waves, until they too sound like the ‘ah-ah-ah’ of the flare-stack. Matilde Nardelli argues that as Giuliana’s condition worsens, the film’s editing becomes more conspicuous and disturbing:

[I]n ways that have some affinity with Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad [and its] effort to find a cinematic articulation of memory and its ambiguities or failures, the visibility of the cut is overtly associated with an articulation of Giuliana’s disturbed mental state. […] The ‘psychic machinery’ that Antonioni’s film models and enacts is one that misses beats and gets stuck.3

Indeed, this surf-edit brings to mind two moments in Marienbad and Le bonheur: in the former, the repeated dolly shot towards A that seems like a compulsive re-enactment (or re-writing) of some crucial encounter between her and X; and in the latter, the equally compulsive repetition of the moment when François clutches Thérèse’s drowned body on the bank of the river.

In Last Year at Marienbad, the dolly-shot brings about an increased proximity that is both desired and feared, expressing a conflicted feeling of ‘I must approach her’ and ‘I must not touch her.’ This is X’s point of view: A opens her arms to embrace him and smiles ecstatically (‘She wants me’), but this is a fantasy that will be undone if he gets too close, if she becomes too real.

In Le bonheur, we might at first think we are seeing a reiteration of a traumatic moment (the discovery that Thérèse has drowned) that François cannot move on from, or that he thinks can be redeemed if he replays it often enough. But there is something tellingly false about the editing, which lends a mechanical air to this moment. It is something like the story François will tell about his wife’s death, how he has processed it a thousand times in his mind, how he wishes he could go back and save Thérèse. We know, watching the film, that these are multiple re-takes in which an actor deliberately repeats the same gestures over and over again, so on some level we know that François’s grief is a kind of act.

In Red Desert, we seem to be seeing the repeated surf-images from the perspective of the young girl: she sees the wave, then immediately replays it in her mind from a closer angle, like the photographer in Blow-Up trying to comprehend the moment he has photographed by blowing it up and replaying it. Something about the image changes in the blow-up/replay process. The photographer is desperate to strip away the fantasy of the peaceful park and expose the violent truth underneath, but for him (as for X in Marienbad) it is impossible to ‘touch’ the reality he keeps trying to zoom in on without making it disintegrate.

In the close-up of the lapping wave in Red Desert, we no longer see the beach and the surf in relation to the ocean and the sky, we see only this single threshold – and this brief threshold moment – where water erupts into a white foam before turning transparent again, thereby creating, marking, but then smoothing over the difference between sea and land.

Why, the girl may be wondering, am I now on the land and not in the water? What is the difference between these planes of existence? What happens in that moment when the one plane turns into the other? Giuliana was afraid that looking at the sea would make her lose interest in the land, that her whole being would be absorbed by this endlessly changeable elemental force (see Part 22). Even in her escapist fantasy, and even before the appearance of the mysterious ship and the singing voice, Giuliana cannot keep these disturbing thoughts at bay.

The fantasy is, effectively, a short film-within-a-film, and film too is an endlessly changeable elemental force. If this sequence ostensibly shows how the camera can record and accurately reproduce reality (including its natural colours), it is also about how the camera can alter and misrepresent reality, or record the ways in which the human mind alters and misrepresents reality. ‘You know,’ Antonioni said to Robert Benayoun, ‘the sand is in reality much more pink than in the film. The one time when I wanted natural colours, the technology [technique] failed me. The island is much more beautiful.’4 Although he saw this as a failure, arguably it serves the meaning of this sequence, in which even a concerted effort to remain close to ‘nature’ cannot stave off the inevitable red-desert-ification of nature and its colours and sounds. This is a performance of nature, like François’s performance of grief in Le bonheur, and the film-maker’s technique serves to expose this performative quality.

As I said above, the vero veliero evokes naturalness and authenticity, but in a way that ends up evoking a sense of how lost and distant these things are. It also compromises the boundaries of our world, between here and gone, animate and inanimate, past and present.

Immediately after the ship has left, and as if in response to its departure, the mysterious voice starts singing. Although there is no clear causal relationship between them, the two phenomena seem interdependent. This story is like a free-associating improvisation by Giuliana, in which she tries to express something through the tableau of the girl in the cove, then through the appearance of the ship, then through the unearthly song. Like Giuliana’s gradual, hesitant self-revelations with Corrado, each improvised element of her story gropes towards a revelation of the truth.

The singing voice, like the ship, is both inescapably present – it is loud and imposing – and completely inaccessible. It seems to emerge out of this idyllic natural setting, but not from any one part of the setting. We see the girl listening to the song in a wide shot, with the entire cove visible, then in a close-up in which the camera circles around the girl and she looks from one place to another, surrounded by this voice in a way that does not seem wholly (or even primarily) pleasant.

The girl hears it coming from the sea, then from the rocks, and eventually when Valerio asks who was singing, Giuliana-as-narrator simply replies, ‘Tutti cantavi...tutti.’ This could mean ‘everyone’ or ‘everything,’ and the ambiguity of the Italian word tutti (it is said twice so that we can take in both meanings) allows for a powerful expression of Giuliana’s melded-together vision of the world. Inanimate objects could be singing, and could be thought of in the same way as people – this is one of the disturbing ideas that the bedtime story communicates. Murray Pomerance points out the musical connotations of the wording here:

In a tutti passage, every member of the orchestra (and chorus) participates in making music at once. If Giuliana believes ‘everyone’ is singing, this ‘everyone’ is figuratively the rocks, the beach, the rabbit, the waters, the boat, the sky; yet what we hear is a female soprano solo, as though perhaps to indicate that Giuliana sees herself as ‘everyone,’ and sees ‘everyone’ as herself. On an oil rig, chatting with Corrado about his travels to South America, she mentions that if she were going away she would take ‘everything,’ and yet we must wonder, does she mean by this, only herself?5

With this last question in mind, we might remember that in the title sequence, the singing voice gradually took over the soundtrack, drowning out and replacing the factory noises, leaving ‘only herself’ – only the female soprano solo. However, as Giuliana will say later in the film, she is not a donna sola, and when she says that tutti cantavi, she is trying to express something like the feeling (referred to by Pomerance) that she expressed on the SAROM rig: that sense that, unlike Corrado, she could not take ‘only herself’ to a new place, but must have the people and things she feels attached to. The soprano voice is like an instrument that resonates to the touch of its whole environment. It is individual and yet somehow expressive of everyone, everything.

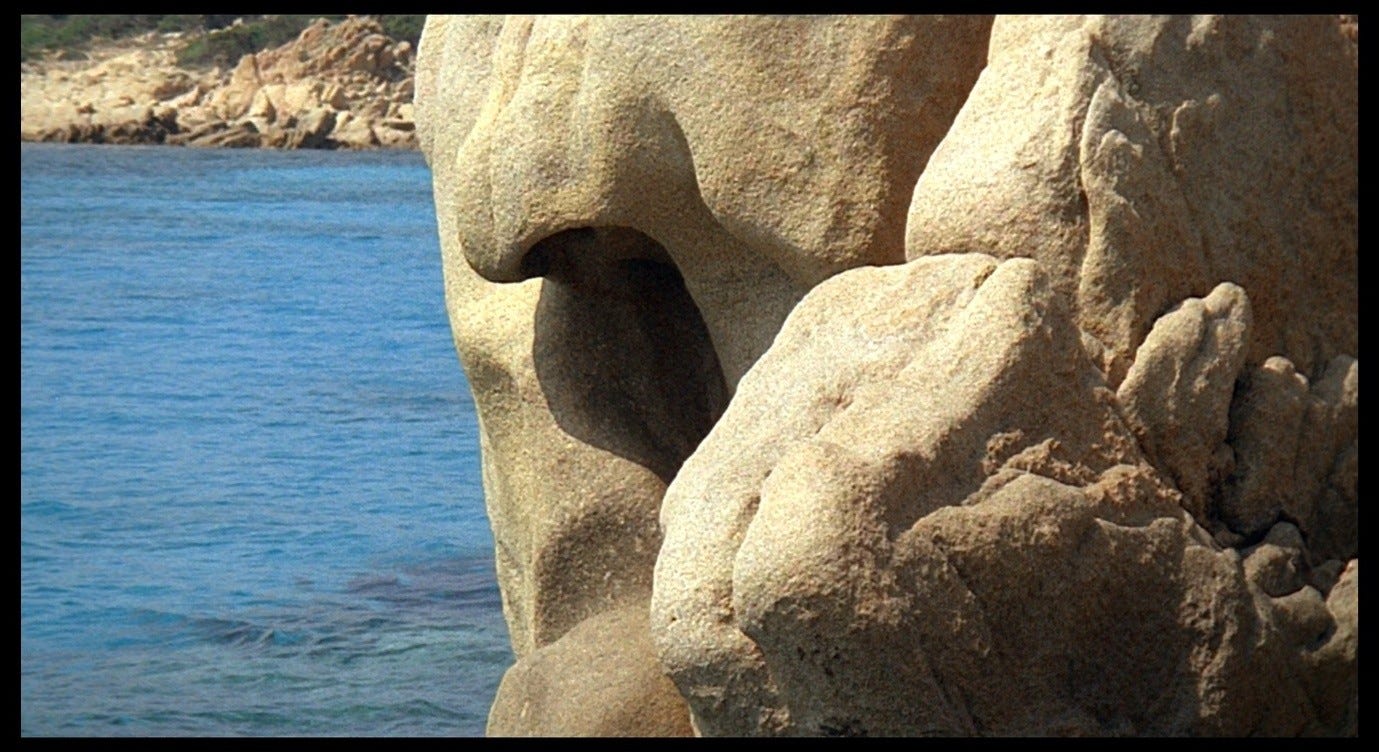

The idea that the voice might be coming from the rocks prompts Giuliana-as-narrator to drift into vague improvisations about this encounter with an overwhelming multiplicity of bodies: ‘So many rocks that...she had never noticed before...they were like flesh...and the voice in that place was very sweet.’ Rather than seeing ‘oneself as everyone,’ or seeing ‘everyone as oneself,’ what happens here seems more like a dissolution of the ‘self’ within the ‘everyone.’ In a way, Giuliana is trying to explain how she ends up feeling like ‘no one’ when the entire universe resonates with her. The girl in the story frequently looks at the camera with a quizzical expression, as though wondering what Giuliana will make happen next, or what role she (the girl) is expected to play.

At this point in the story, in response to the inexplicable mysteries that have been visited on her, the girl’s happy mood fades away. She is ultimately left with nothing to do but look around her in confusion (as Giuliana does at many moments throughout Red Desert), while the camera slowly loses interest in her.

When the narrator comments on the flesh-like rocks and the sweetness of the voice, are these the girl’s thoughts as narrated by Giuliana, or simply Giuliana’s thoughts? Is the narrator’s voice like that of the soprano singer, a sweet but all-consuming ‘everything’ that quietly obliterates the individual? And is this therefore an allegory for how the modern world discards those who cannot adapt to its dizzying changes?

For Elena Past,

the most important feature of the Budelli Island sequence is the agency imparted to nonhuman actors. These include water, rocks, nonhuman animals, inhuman and nonhuman sounds, and the sailing ship. All are things we see and hear in other parts of the film, but now they are focalized by Giuliana’s voiceover, and by the gaze of a young girl, often squinting, who is perplexed by them. On the island, the preoccupations Giuliana has voiced elsewhere come into focus, confronting us with their material and ontological weight. The voiceover casts these concerns as ‘mysteries,’ numbering two: the mystery of the unmanned sailing ship (who sails it?), and the mystery of the bodiless voice (who sings?). How, the question seems to run, can things move and speak without anthropic power?6

This is a little like asking, ‘How can “no one” and “everyone” co-exist in the same space?’ Imparting agency to nonhuman actors recalls Giuliana’s claim to be personally attached to her ashtrays and to everything she has sottomano (in the conversation on the SAROM rig). Like Restivo, Past sees the island sequence as tying together motifs from the rest of the film, and this also dovetails with Pomerance’s reading of the word tutti in terms of a musical ensemble all playing at once. These two mysteries, of the ship and the song, raise questions of such ‘material and ontological weight’ that they apply throughout Red Desert. What is especially striking about Past’s formulation of the overall mystery is that it sounds like a question one might ask about a machine, or especially a robot: the piloted vessel and the sung melody both require anthropic power, and yet neither has it, so they elicit the same sense of wonder that an android might; they are in a sense ‘automatic.’ The anxiety of the person who cannot cope with the technological advances of the modern world is thus unfurled into a broader kind of anxiety, perhaps triggered by robots but spilling out into the person’s relationship with all the nonhuman actors around them.

When we heard this same song during the title sequence, it was juxtaposed with blurred images of the industrial complex, and with the hum of machinery and the bleeping of electronic music (see Part 4). The juxtaposition had a complex effect: the voice seemed more ‘human’ than the other elements of the image and the soundtrack, but also weirdly alien and perhaps artificial, its repeated ‘ah-ah-ah’ motif sounding like an anxious breathing exercise and a rhythmic industrial process at the same time.

Now we hear the song over in-focus images of the idyllic cove, and again it feels ambivalently ‘of this place’ and ‘not of this place.’ The song seems to emerge from natural phenomena – the sea, then the rocks – and yet also from nowhere in particular. It is, according to the narrator, ‘very sweet,’ in accord with the beauty and serenity of the cove, and yet it still sounds anxious, and is clearly a disturbing intrusion into the girl’s carefree playtime. When you squint at the factories, they blur until you might as well be looking at a forest. Their mechanical noises can sound like music, and a human voice can sound like a mechanical noise. Likewise, a beautiful pink beach devoid of people and artificial objects can suddenly become a collective amalgamation of people (tutti), singing that strange, sweet factory music.

This is, appropriately enough, a confusing and mysterious sequence, but it may become easier to understand if we focus on two key aspects of the song: the fact that we are hearing it for a second time and the fact that it brings Giuliana’s story to an end. The song’s appearance over the opening credits suggests that it is a crucial, defining element in Red Desert, and its recurrence now marks this as a crucial, defining sequence. However, the song is also what causes Giuliana’s bedtime story to run aground. It is while talking about the song that she becomes distracted from the protagonist of her own tale. She is so hypnotised by this sweet, haunting sound that she simply allows the narrative to fizzle out. Images of rocks that look like human bodies crowd the frame in shot after shot, until we lose our grasp on the difference between a rock and a body, or our grasp on what is happening in this scene.

After one final, slightly haunting image of a rock that looks like a skull (peering out at us from the shadows), the image blurs out altogether as the camera pans over sea and rocks, dissolving everything into a continuous haze that transitions meaninglessly between blue and pink.

This recalls the opening shot of the fantasy-cove sequence, which showed a green-brown blur of vegetation, then tilted down to the pinkish-white blur of the sand and the blue blur of the sea, before settling on the in-focus young girl floating in the water.

Giuliana’s fantasy emerges from the same kind of unfocused maelstrom we saw in the title sequence, and it regresses back into that maelstrom as it comes to its unsatisfying conclusion.

Hearing the song and remembering it from the title sequence, we think that something important will happen now, something that will be essential to our understanding of and engagement with the film. But the climax of Giuliana’s story, if it feels revelatory at all, reveals something through a kind of anti-climax, by ending with a spiral into the void rather than a coherent resolution. Giuliana gropes for a way to bond with her son, a way to explain her own condition, a way to express what she wants or to picture a life that would be more tolerable than her own, but at every stage she loses her grip: the ocean starts to sound like a machine, the marvellous ship evokes a lost world, the sweet song annihilates reality.

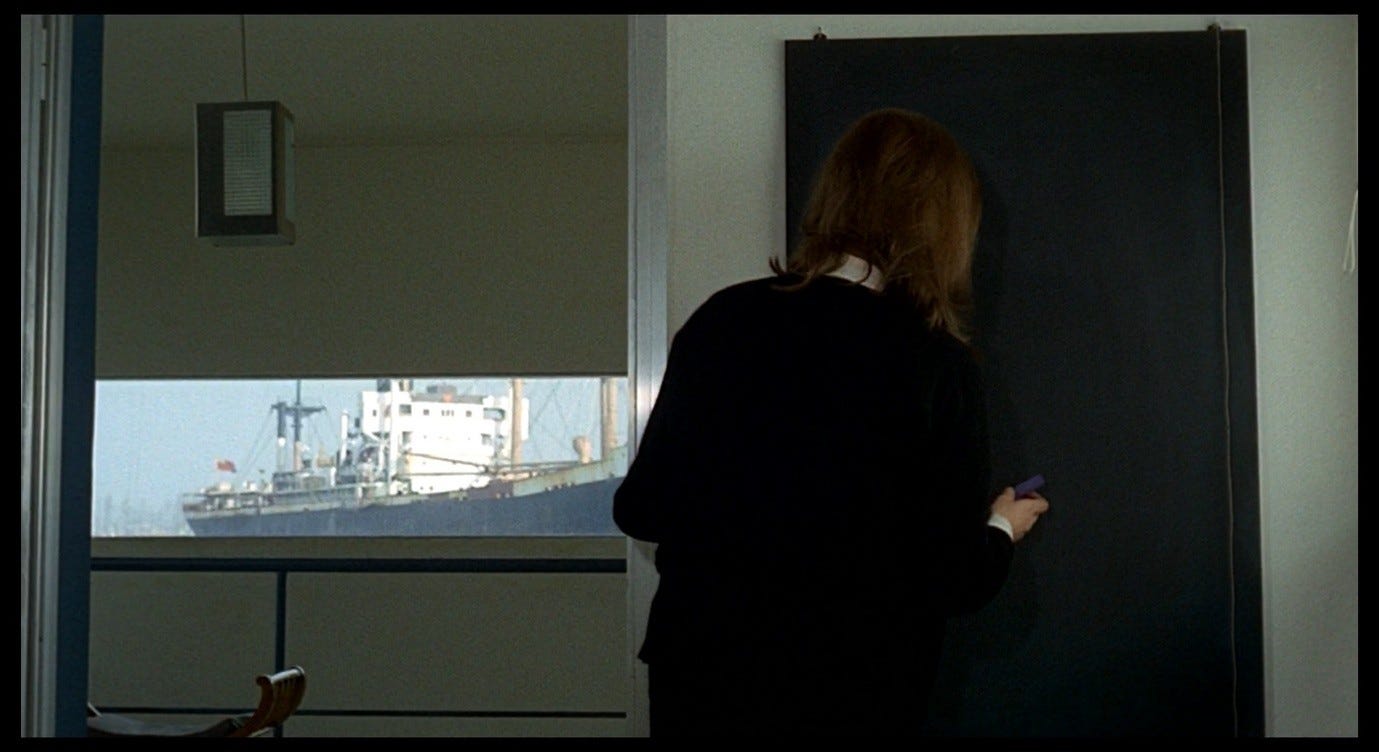

We cut from the blurred final image of Giuliana’s story to a shot of Giuliana herself, with her environment (including the landing and the Dante chair from the night-terrors scene) perfectly in focus behind her. At first she is looking down, then she looks up slowly and exhaustedly at the docks outside. A low mechanical roaring noise can be heard in the background.

After the pink beach, the colours in this image – even Giuliana’s red hair – seem exceedingly drab, and when we cut to the reverse-shot of the docks, the huge tanker outside makes for a depressing contrast with the vero veliero that visited the fantasy cove.

The tanker is matte-coloured blue and red, echoing the small boats from Giuliana’s story that were differentiated from the more impressive, mysterious vessel.

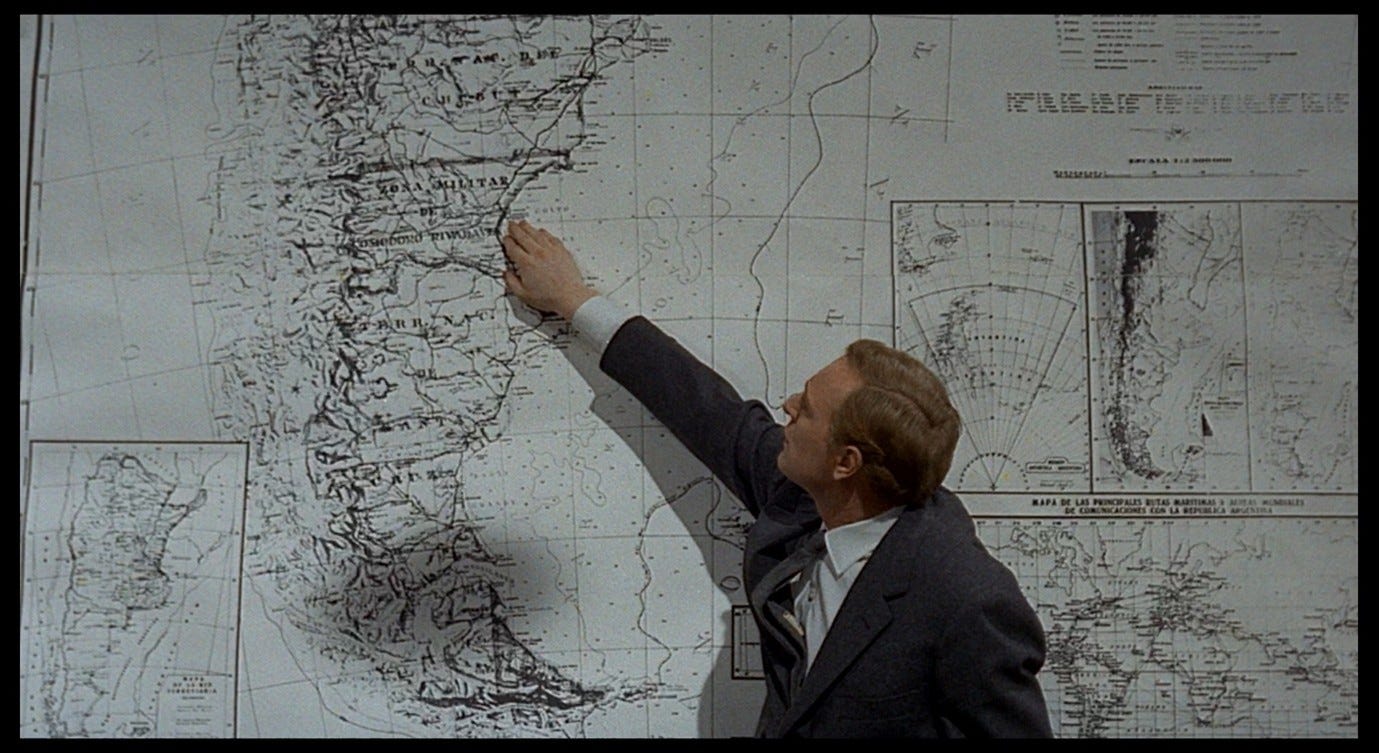

In the real world, however, the equivalents of those meagre little boats are overwhelmingly massive. They ‘navigate the straited space of the sea in pursuit of capitalist surplus value,’ as Richard Letteri says, while the mysterious veliero seems engaged in a ‘more nomadic wandering [whose] erratic movement “map[s]” the space of the sea as compared to Corrado’s restrictive “tracing” […] with his finger on the map of Argentina.’7 The latter gesture epitomises Broch’s ‘singleness of purpose,’ accompanying as it does Corrado’s forecast of the route he and his team will travel in order to reach their destination.

At this point in history, when there is no more mapping left to do in the world, a vessel has little choice but to trace a journey from one point to another, unless it operates within a fantasy about discovering new, uncharted territory ‘beyond this world.’ After we see the huge tanker outside Giuliana’s window, the next shot gives us a wider perspective of the Ravenna port, whose monochrome appearance reflects the industrial singleness of purpose as well.

We see what looks like a bleak, ruined field in the distance on the left, then the grey canal running parallel to the grey docks, grey stone structures towering over the whole scene on the right, and various industrial paraphernalia (trucks, planks, a large crane) scattered around. We then cut back to Giuliana’s weary face, staring at all this.

The transition from cove to harbour might seem to suggest that there is something about the contrast between the idyllic world of the story and the real world of Ravenna that causes Giuliana’s depression. If only she could live in that cove, she might not be in this state of crisis. But as we have seen, the story is more complex than that. The cove itself becomes a compromised, problematic space, and in a sense it morphs back into the ‘real’ world rather than simply being contrasted with it. Giuliana’s story is a fantasy that she tries to sustain, but that finally breaks down and gives way to reality.

The windows of her apartment are featured prominently in this sequence, especially one wide, narrow window through which a ship can always be seen passing.

The story of the pink beach is a phenomenon that occurs in Giuliana’s mind while she is looking out of these windows. She dreams of a faraway place as unlike this one as possible, but cannot stop the mysterious ships from passing (always at a distance and inaccessible) or the mysterious voice from singing (the industrial humming and ah-ah-ah noise that pervade her reality). Even the supposed ‘naturalness’ of the place she imagines cannot stand up to scrutiny. Perhaps, Giuliana reflects as she spins her tale, the problem is not an antithesis between nature and industry, but the presence of some force within nature that is as sweet as it is terrible. The beautiful colours, the flora and fauna, the magnificent old-style vessel, and the primal song of the rocks all come to seem like components of a misguided fantasy. Rather than saving Giuliana from her existential crisis, they would if anything re-trigger it. And so the dream breaks down and she looks up to see her familiar, drably coloured environment hemming her in as always.

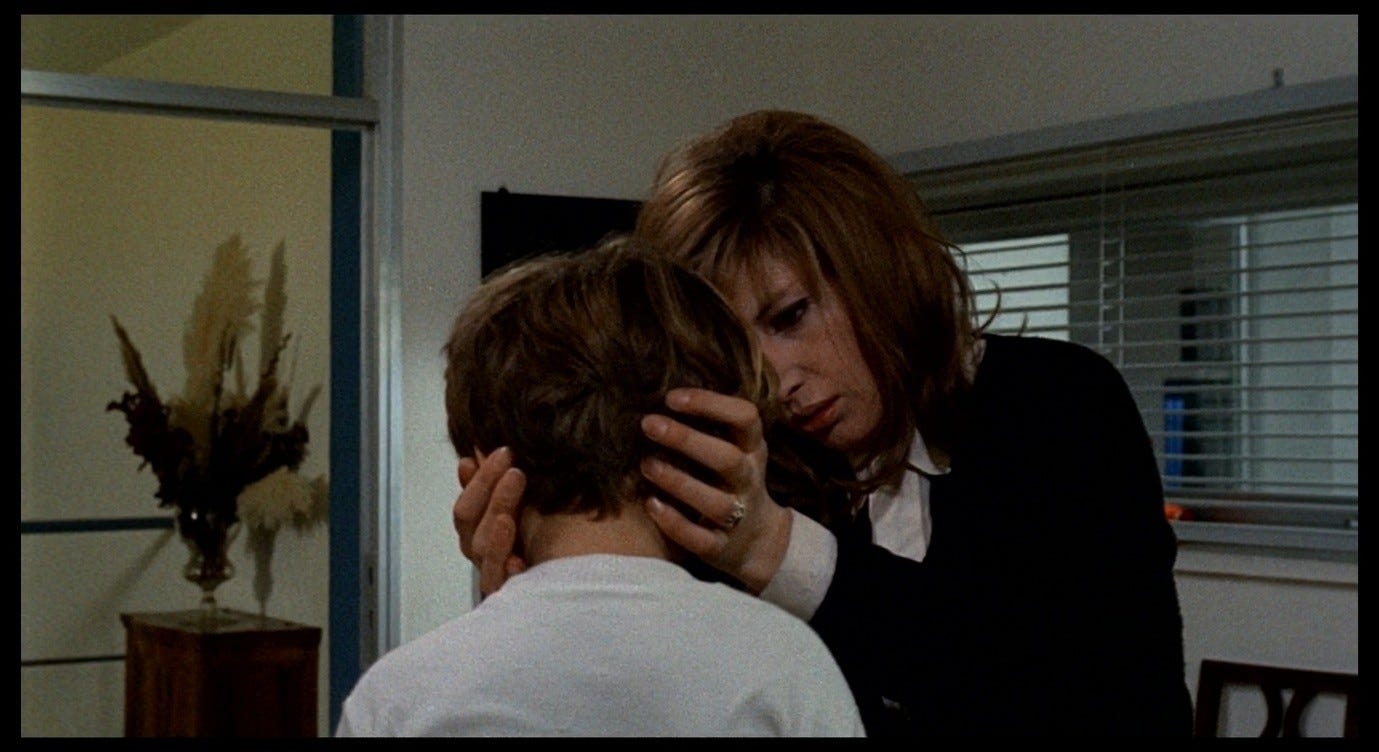

Still half-immersed in the dream-state, Giuliana does not hear her maid trying to get her attention (so she can hand over the mail), and has to be ‘woken up.’

Then, finding Valerio on his feet and un-paralysed (see Part 33), she again takes a minute to grasp the reality in front of her, and again has to be woken up, this time by the cold, diverted face of her son.

In the simplest terms, her story expressed a desire to live in a world that would meet her needs, but Giuliana cannot escape the reality in which none of her needs are met, and in which her own son has (as she thinks) no need of her.

Seymour Chatman, describing the various attempts at escape in Red Desert, draws a link between the observatory towers at Medicina (which ‘hint at [voyages] into the reaches of outer space’) and the mysterious ship in Giuliana’s story which also ‘represents a fantasy of escape […] roar[ing] in from nowhere and turn[ing] about, without deigning to land.’8 This link suggests a parallel with two other self-deconstructing stories of out-of-this-world escape, in Fellini’s 8½ and Antonioni’s Identification of a Woman.

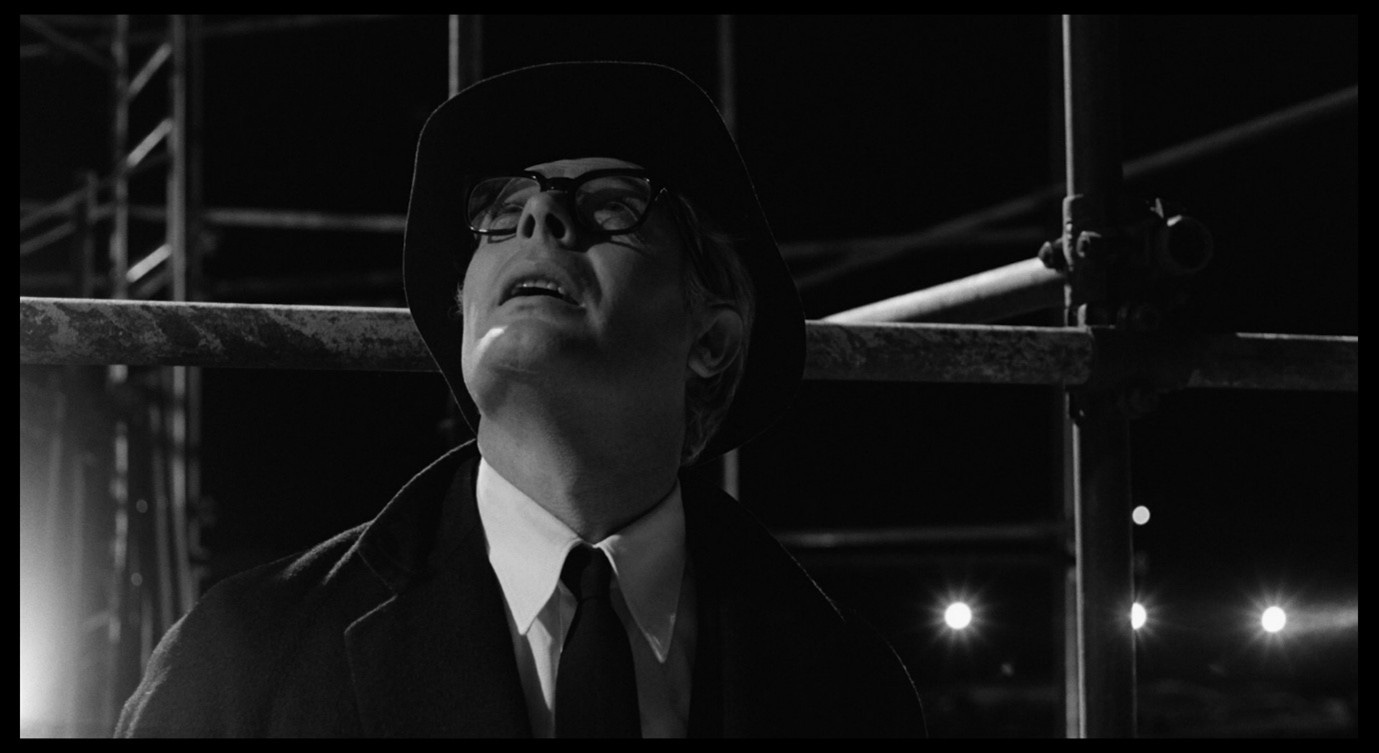

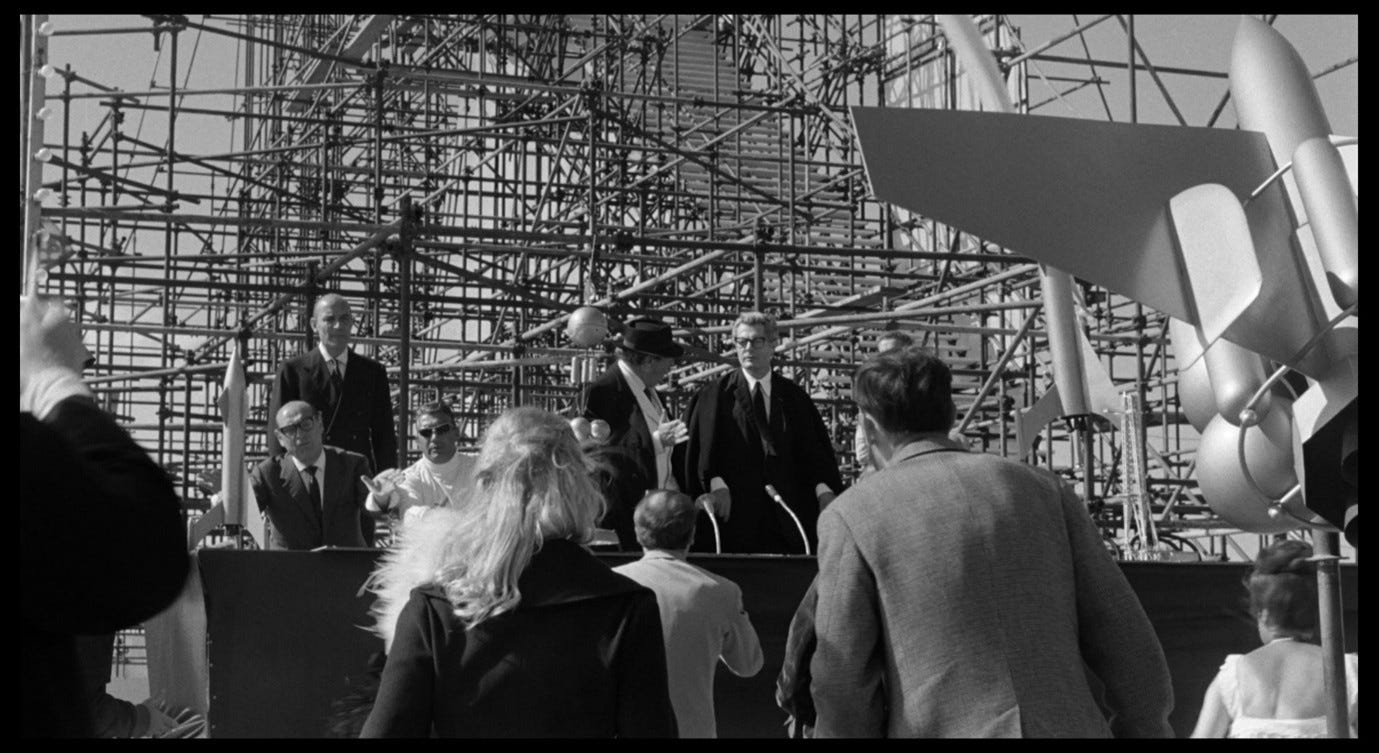

Guido Anselmi, the director around whose creative crisis 8½ revolves, is trying to make a science fiction film about the remnants of humanity escaping in a spaceship after a thermonuclear war. A huge set has been built to accommodate the spaceship: a night-time visit to this set shows it surrounded by blinding lights whose coronas look like other-worldly cauls, and on the soundtrack we hear (in John Stubbs’ words) ‘the quivering electronic music we associate with eerie moments in science fiction movies.’9

The matte painting of the spaceship, to be super-imposed on the scaffolding, was inspired (Fellini said) by Bruegel’s Tower of Babel.10

Guido tries to explain that he wants this film to benefit humanity, to dispel the ‘dead things we carry around inside us,’ but as he gapes up at his unwieldy tower, his head fills with confusion.

During this scene, we keep hearing specific figures – the number of extras that will be employed, the height of the tower, the amount of money already spent on it – that serve as an ever-accumulating measure of how much Guido is in over his head. The spaceship set becomes the site of a hellish press conference in which the director is confronted with the impossibility of completing his film.

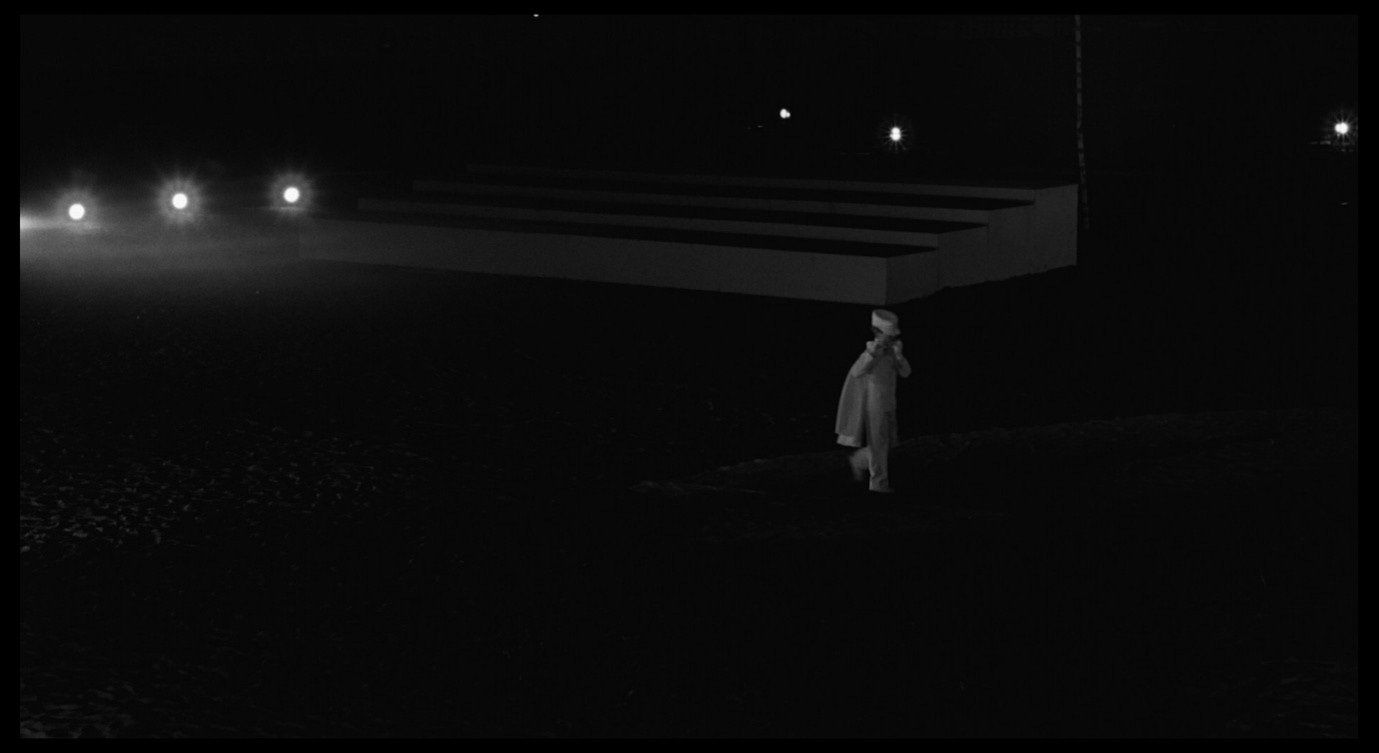

The whole project is too grandiose, it has nothing to say, and everyone hates it before pre-production has even been completed. The nightmare ends with Guido shooting himself, and we then cut back to ‘reality’ to find him ordering the deconstruction of the tower.

This in turn triggers the redemptive ending of the film, in which all Guido’s loved ones magically appear, descending from the tower rather than ascending into it, as though they were disembarking from the spaceship. They dance, with Guido, hand-in-hand around a circus ring, until darkness falls and we are left with only a little boy playing a flute in a gradually fading spotlight.

The Babel-esque launch tower, Stubbs argues,

is wrong as a dominant image for Guido’s movie. Guido cannot and finally will not give up his past, those things that have marked him psychologically, to make the kind of utterly new start implied by the idea of blasting off from the launch tower in a spaceship. Guido is too much the sum of his previous experiences. […] Guido as a creative artist clears away false visual images and leaves the field of his mental activity open for the discovery of other images that will work. The two new visual images that Guido finds to give his movie an organizational concept are the group of major characters in white, as opposed to the single character, and the circle, as opposed to the tower.11

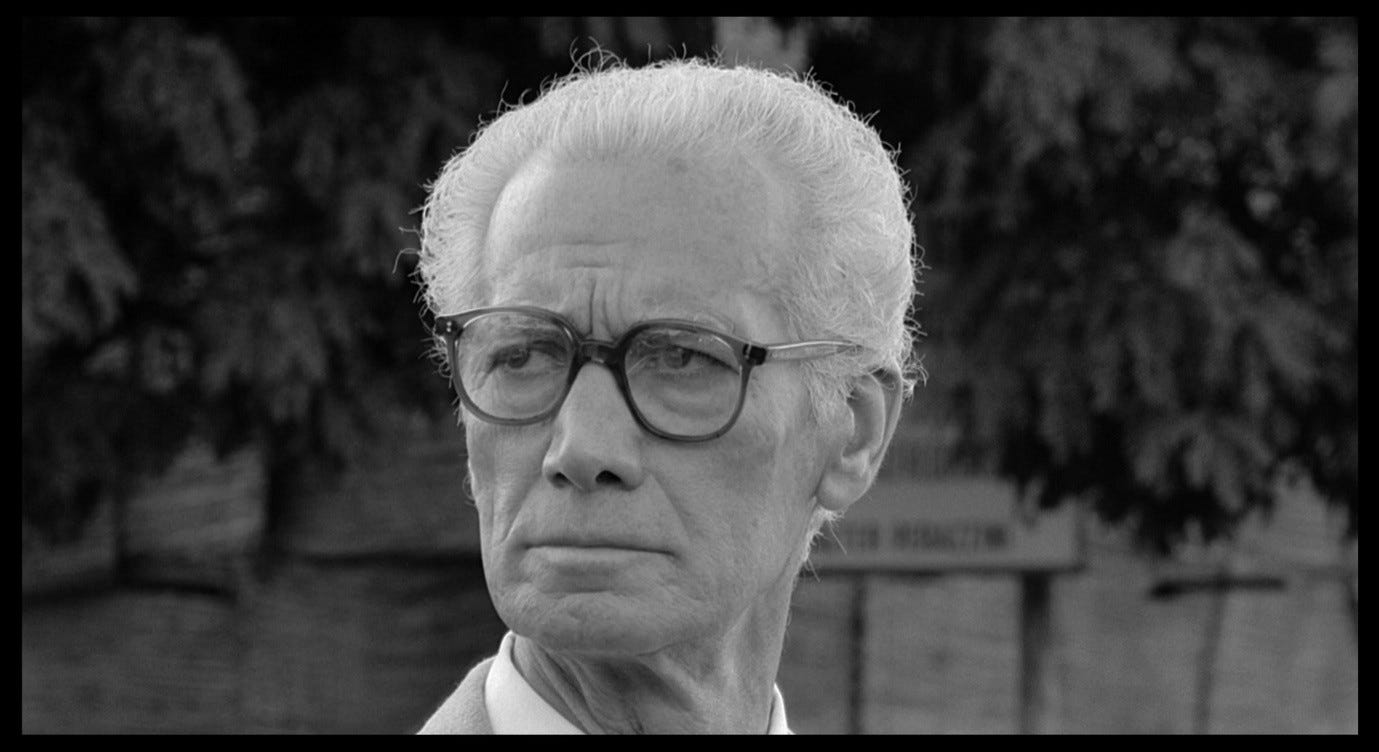

In several ways, Guido’s crisis and his abortive attempt to solve it are like Giuliana’s. He feels that he is living in a world ruined by modernity, in this case manifested as nuclear war (in an echo of the final scene of L’eclisse – and the white-haired man from that scene appears, in another striking close-up, as an extra in 8½, shot by the same cinematographer).

Guido concocts a story in which humanity escapes from its ruined past into a brighter future, but the parallel with Babel and the uncertainty of the spaceship’s destination expose this as a vague fantasy born out of denial. Guido’s sense of humanity’s problems is in fact rooted in his own problems, and the fleeing spaceship represents his desire to be free from the accumulated relationships of his past. This metaphor of escape is replaced by one of benevolent entrapment: the hand-holding circle of messy human connections, dancing to a manic but joyful circus melody, and resolving finally to its essence, a child playing a flute. This, the film concludes, is all the artist really is, and all a human being really is – not a grand figure who can solve the world’s problems, just a child singing a very personal song for as long as the spotlight (another kind of circle) allows.

Identification of a Woman also centres on a film director, although Niccolò Farra’s creative crisis is less dramatic and consequential than Guido’s. His conception of his next film is vague, except that he knows the main character should be a woman. How, his producer asks, can he think of telling more love stories in our messy, corrupt modern world? Corruption, Niccolò retorts, is the glue that holds society together, and the corrupt are the first to buy into love stories. But like Guido in 8½, he will gravitate away from the personal in an attempt to escape from the ruins of the modern world, and unlike Guido he will not (within the confines of this film) revert back to a focus on personal connections. Niccolò’s quasi-relationships with Mavi and Ida prove so futile and unsatisfying that no hand-holding circus fantasy could redeem them, and this film concludes with a different kind of circular image: that of the blazing sun.

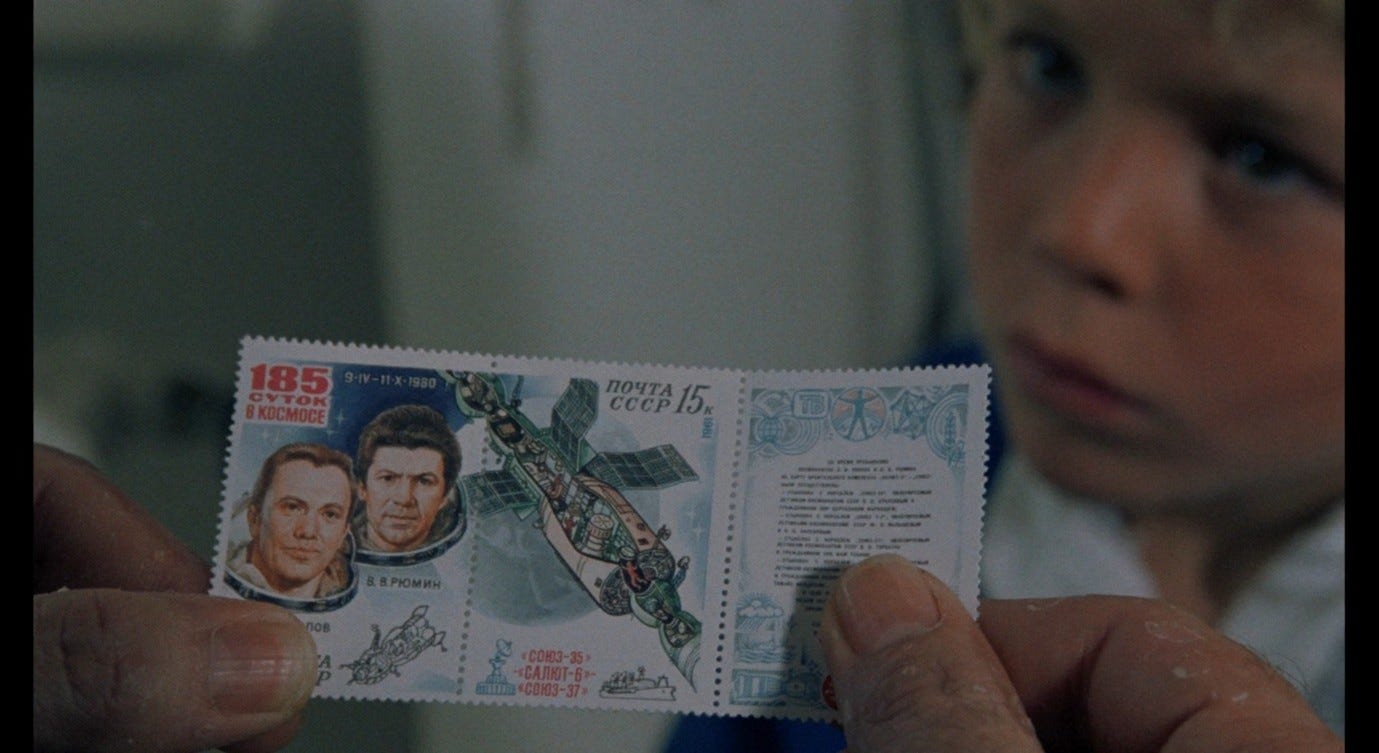

This ending is foreshadowed when Niccolò’s nephew suggests, in the same tone with which Valerio demands a story from Giuliana, that he make a science-fiction film.

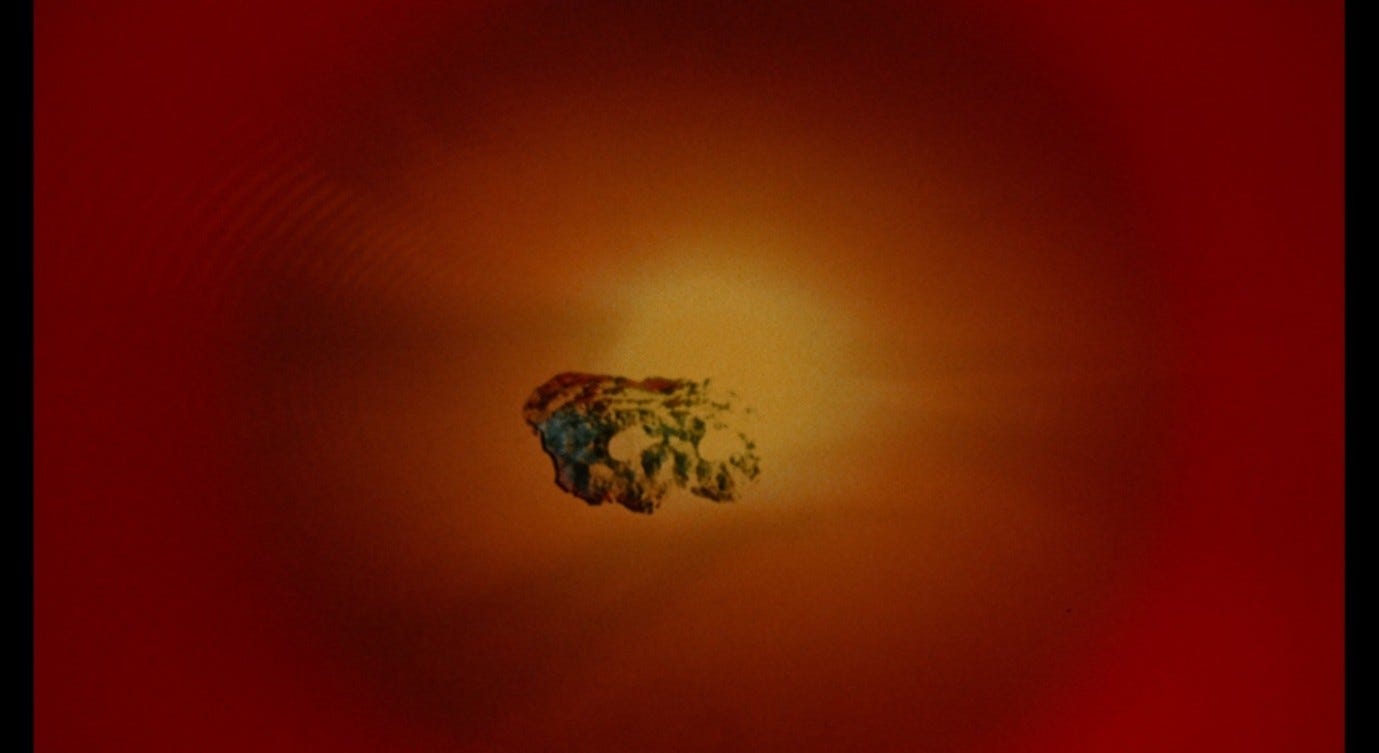

He shows his uncle a stamp commemorating the Russian astronauts who, in 1980, broke the record for the longest period of time spent in space (185 days). We hear the throbbing baseline and drumbeat of Japan’s ‘Sons of Pioneers’ on the soundtrack as Niccolò looks at a telescopic image of the sun. The fiery orange mass fills the left-hand part of the screen and emits a wavering reddish haze into the blackness on the right.

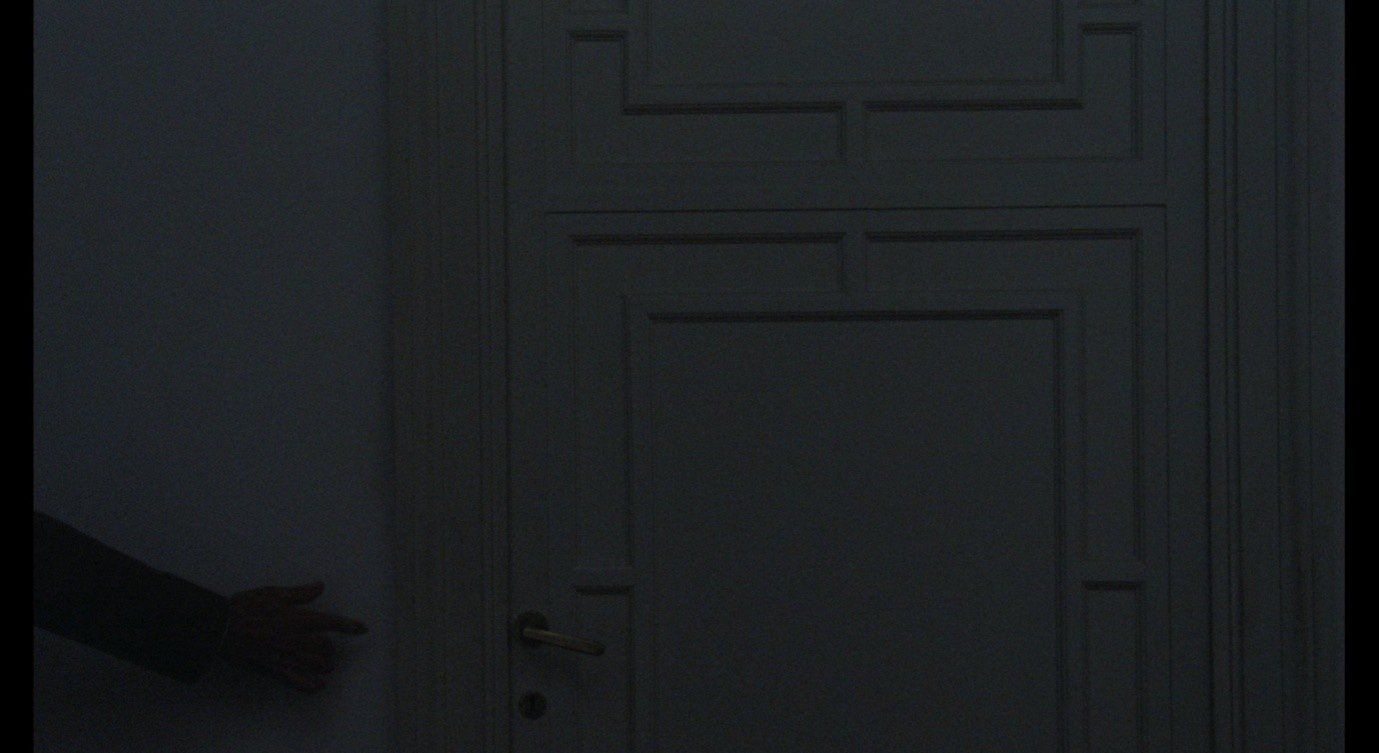

Like the hard-to-identify women (or ‘woman’) Niccolò is fixated on, the sun appears to be an elusive entity, incapable of being fully seen or photographed, always in flux and indefinable. When the director commits to his sci-fi concept at the end of the film, he does so (a little like Guido) with an air of playfulness, hesitating to go back to his study but then allowing himself to be dragged inside by his fingers as they tip-toe along the wall.

Rather than looking through the telescope again, or even through his sunglasses, he simply closes his eyes; and rather than building a vast set, he imagines a low-budget spaceship (clearly made from silver foil) flying towards a less-than-realistic sun. Like Giuliana, he recounts his fantasy to the child who requested it: we hear the nephew asking questions, to which Niccolò responds by explaining, ‘You can never tell, in science fiction, what is realistic and what isn’t.

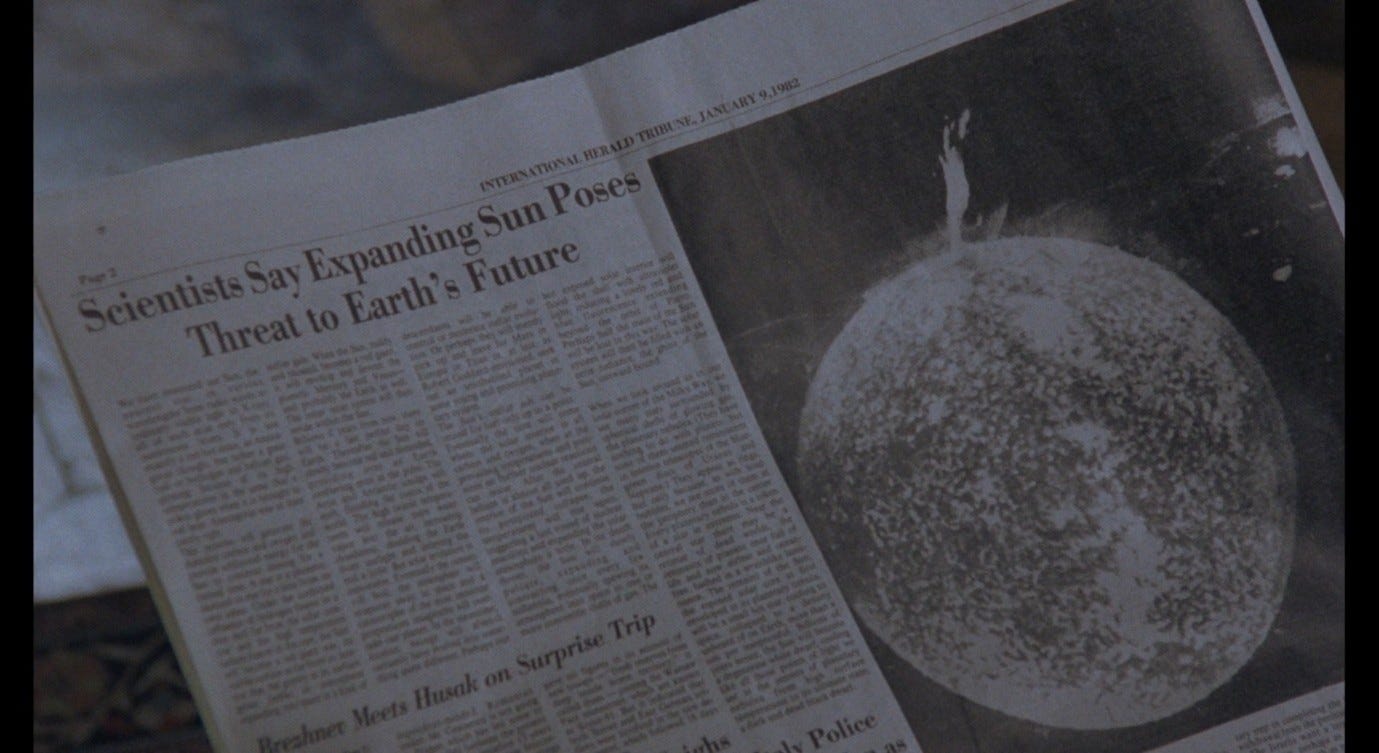

Earlier, he had seen a newspaper headline, ‘Scientists Say Expanding Sun Poses Threat to Earth’s Future’.

In his proposed next film, a spaceship will travel into the depths of the sun to reveal its workings, and to reveal, in the process, ‘la ragione di tante cose.’ The many things whose ragione (reason) will be discovered are not specified, but the implication is that this voyage will solve not only the looming threat to our planet but also the interpersonal problems this film has largely focused on. In another echo of 8½’s ending, Antonioni gives the final word to the child: ‘And then [E dopo]?’ the nephew asks. A low, booming note rings out dramatically from John Foxx’s electronic score, recalling the deep base notes of ‘Sons of Pioneers’ from earlier. The end-credits roll without the nephew’s question being answered, but the music suggests a kind of answer from deep within the sun, like those rumori delle stelle being picked up by the Medicina observatory. As we saw in Part 10, eerie electronic noises can be suggestive not only of futuristic technology, but also of mysterious forces deep within the earth, or in this case deep within the sun.

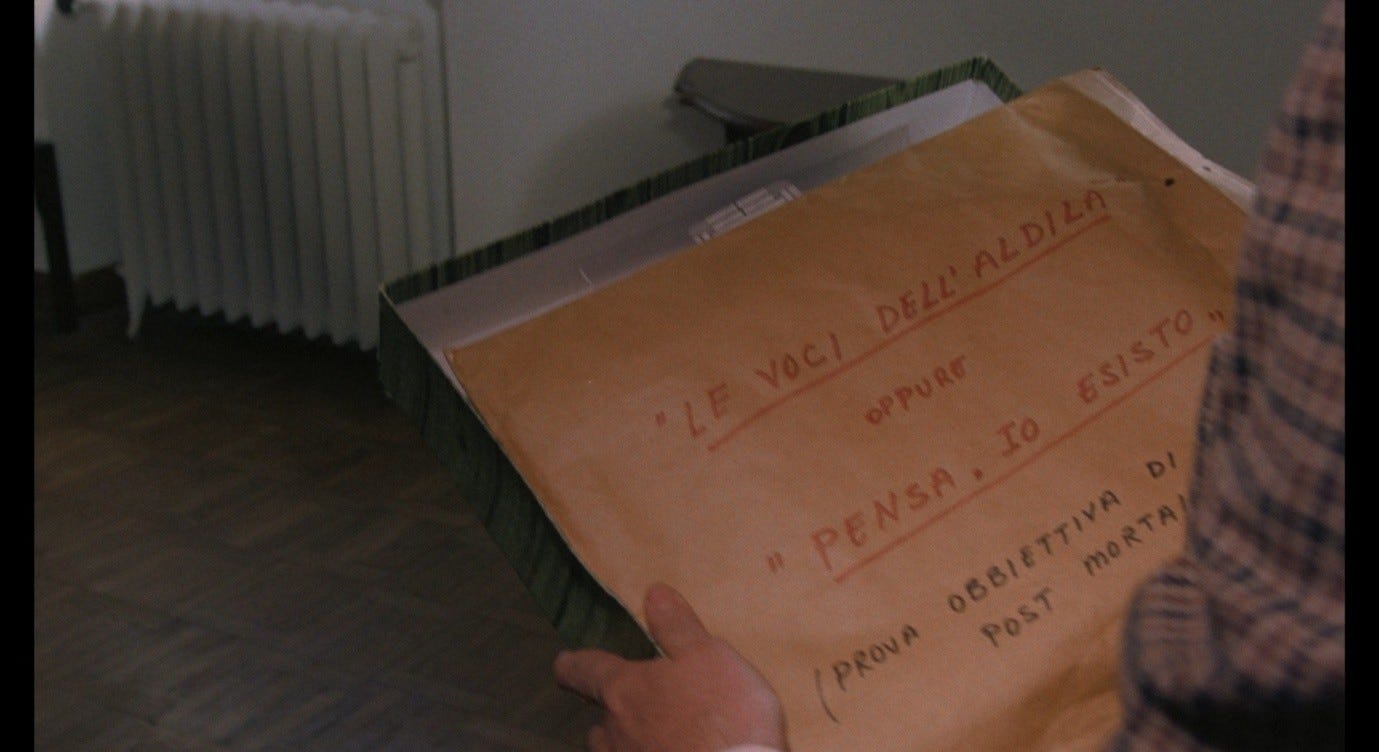

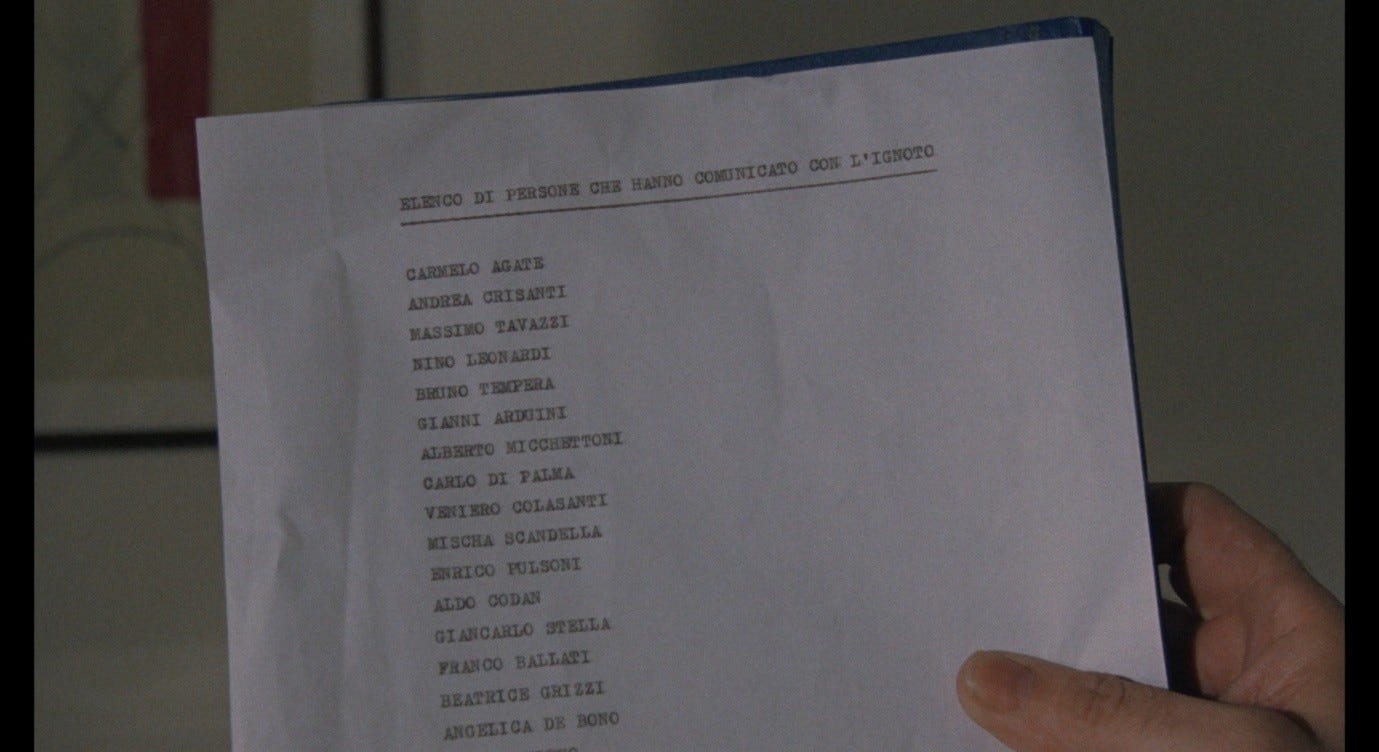

Suppose we do discover the ragione operating within the sun, within the world, and within human relationships? What happens after that? We might remember the unsolicited film-script Niccolò received, Voices from the Beyond; or, Think, I Exist (objective proof of life after death). A letter accompanying the script said the director would have total creative control, and provided a list of people who had communicated with ‘the unknown [ignoto],’ including Carlo di Palma, the cinematographer on Red Desert and Identification of a Woman.

‘Maybe I should contact one of these people,’ mutters Niccolò, before wearily repeating ‘Oh god’ as he contemplates this comically un-filmable script. However, the reference to voices from al di là – the beyond, the afterlife – is as prophetic as the commemorative stamp, because the sci-fi fantasy at the end is not only about the acquisition of knowledge from the sun’s interior, it is also about the ignoto, the corona of mingled darkness and light around the sun, so beautifully captured by di Palma. The nephew’s dopo invokes those voices from the beyond, not with reference to the afterlife, but in the same vein as Antonioni’s meditation on the layers of reality (see Part 31), the succession of ‘revealed images’ behind which is either an ‘absolute, mysterious reality that nobody will ever see’ or a ‘decomposition of every image, of every reality.’12

For Fellini, the child-like simplicity of the flute-playing boy was a rebuke to the pretensions of the apocalyptic sci-fi epic, and a redemptive reversion to something more personal and playful. For Antonioni, the child’s rebuke is not associated with simplicity or redemption, but is sterner and more challenging. It accompanies the booming, resonant rebuke of the sun, countering the playfulness and frivolity with which Niccolò embarks on this new project. Like Valerio, Niccolò’s nephew is a vocal critic: he knows a bad story when he hears one. ‘And then?’ is not just an objection to the lack of a second act, it is a critique of the story’s basic premise. Imagining this exploratory mission is like imagining Giuliana’s paradisal pink-sanded cove. It stems from, and indeed embodies, the impasse the storyteller faces with regard to their actual problems. If we understood how the sun worked, we as a species would still be just as doomed as we are now, and if Giuliana lived in that beautiful cove, it would quickly turn back into the grey Ravenna docks.

Budelli itself is, apparently, every bit the idyllic refuge from modernity that Giuliana wanted it to be. A man named Mauro Morandi lived as a hermit on the island from 1989 until his eviction in 2021. Speaking about his return to civilisation, he lamented the loss of his spiaggia rosa: ‘I became so used to the silence. Now it’s continuous noise.’13 He died in January 2025. Giuliana is not like this real-life hermit who actually lived on the island, but more like the film director who ‘lives’ through storytelling and image-making, who tries to capture something of the island’s beauty and quiet, but who can only ever project their internalised desert of continuous noise.

Next: Part 36, The journey to the hotel.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Restivo, Angelo, The Cinema of Economic Miracles: Visuality and Modernization in the Italian Art Film (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), p. 134

Manceaux, Michèle, ‘Dans le Désert rouge’, L’express (16 January 1964), pp. 19-21; p. 20. My translation. An edited version of this interview (which missed out some important details) appeared in English as ‘In the Red Desert’ in Sight and Sound 33, 3 (Summer 1964). Arrowsmith (Poet of Images, p. 85) quotes more of Antonioni’s answer but does not translate ‘vivant’, translates ‘c’est’ as ‘there is’, ‘saignant’ as ‘blood-stained’, and ‘chair’ as ‘bones’. Here is the full passage in French: ‘Ce n’est pas un titre symbolique. Les titres de ce genre ont un cordon ombilical avec l’œuvre. Je ne sais pas très bien pourquoi. Chacun peut y mettre ce qu’il veut. C’est un titre ouvert. “Désert” peut-être parce qu’il n’y a plus beaucoup d’oasis, “rouge” parce que c’est le sang. Le désert saignant, vivant, plein de la chair des hommes.’

Nardelli, Matilde, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), pp. 66, 73

Benayoun, Robert, ‘Le désert rouge’, Positif 66 (1965), pp. 43-59; p. 58 (my translation)

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 80

Past, Elena, Italian Ecocinema: Beyond the Human (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), p. 41

Letteri, Richard, ‘Becoming Giuliana: Antonioni’s Red Desert and the Capitalist Social Machine’, Deleuze and Guattari Studies 15.1 (2021), pp. 91-116; p. 110

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 62

Stubbs, John C., Federico Fellini as Auteur: Seven Aspects of His Films (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2015), p. 143

Stubbs, John C., Federico Fellini as Auteur: Seven Aspects of His Films (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2015), p. 143. Pictured below is Bruegel, Pieter, The Tower of Babel (1563), Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna; image taken from the museum’s website. The alternate version at the Museum Boijimans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam is less like Guido’s spaceship, so is not pictured here.

Stubbs, John C., Federico Fellini as Auteur: Seven Aspects of His Films (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2015), p. 143

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Preface to six films’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 57-70; p. 63. Cooper translates the last sentence as, ‘Or perhaps, not until the decomposition of every image, of every reality,’ suggesting a gesture towards a revelation at the end of the world or the end of life. But the sentence uses the same ‘fino a’ construction as the previous one, which refers to the unveiling of successive layers of images: ‘Fino alla vera imagine’ means ‘Down to the true image,’ and then I think ‘fino alla scomposizione’ means ‘down to the decomposition.’ In other words, Antonioni is not imagining a time when someone will see that ‘true image,’ but rather imagining that peeling back these layers would not even reveal the truth but cause all images and realities to disintegrate. Italian text from Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), p. xiv.

Giuffrida, Angela, ‘Hermit guardian of Budelli dies after three decades on paradise island’, The Guardian (07 January 2025)