Everything That Happens in Red Desert (51)

Our place in the red desert

This post contains a spoiler for This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection.

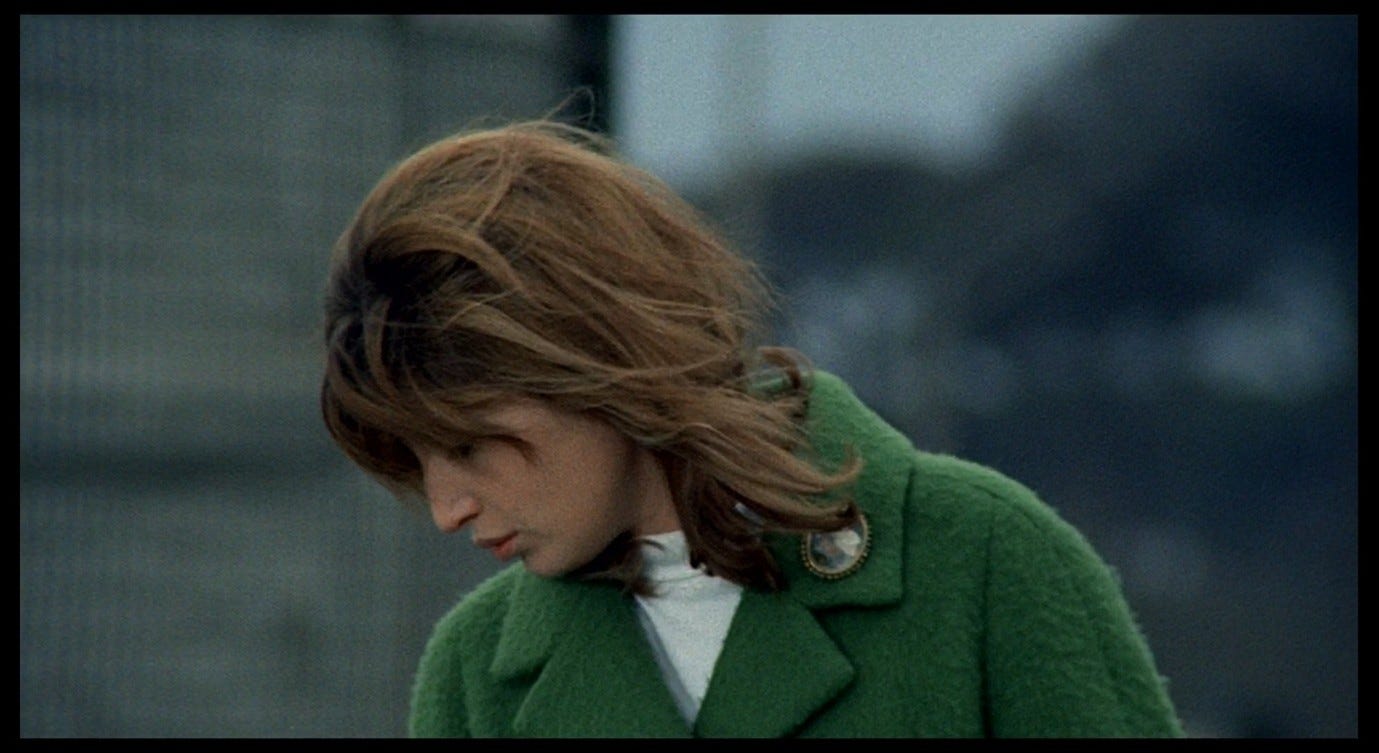

The final scene of Red Desert revolves around two similar moments, in which Valerio detaches from his mother, explores his environment, and asks a question about it. In the first instance, Giuliana finds Valerio playing with a pressure valve in the ground. The ground beneath their feet emits bursts of steam at irregular intervals, and one of these bursts stops Giuliana in her tracks. She stares at the ground and takes her right hand out of her pocket – her other is holding her purse – which gives her a lost, uncertain look that we have seen many times before.

The camera is now positioned at a low angle, close to the ground. We are close to the thing that menaces Giuliana, and the low angle also means that we see something of the scale of the industrial complex around her. In L’Atalante, when Juliette is wandering the streets looking for work, we see her from pavement-level, from the gutter that seems to be drawing her towards it. The environment she walks through appears huge and forbidding (unlike the claustrophobic but cosy barge in which she previously lived).

In Giuliana’s case, the ground is the thing she is afraid of losing, or of sinking into, and the bursts of steam remind her (and us) that she is still not walking on solid ground – that the earth could evaporate into air at any moment.

Valerio wants to know why the steam keeps erupting from the ground, but Giuliana cannot tell him. She takes his hand and leads him away; he looks back over his shoulder as he hears the next burst of steam.

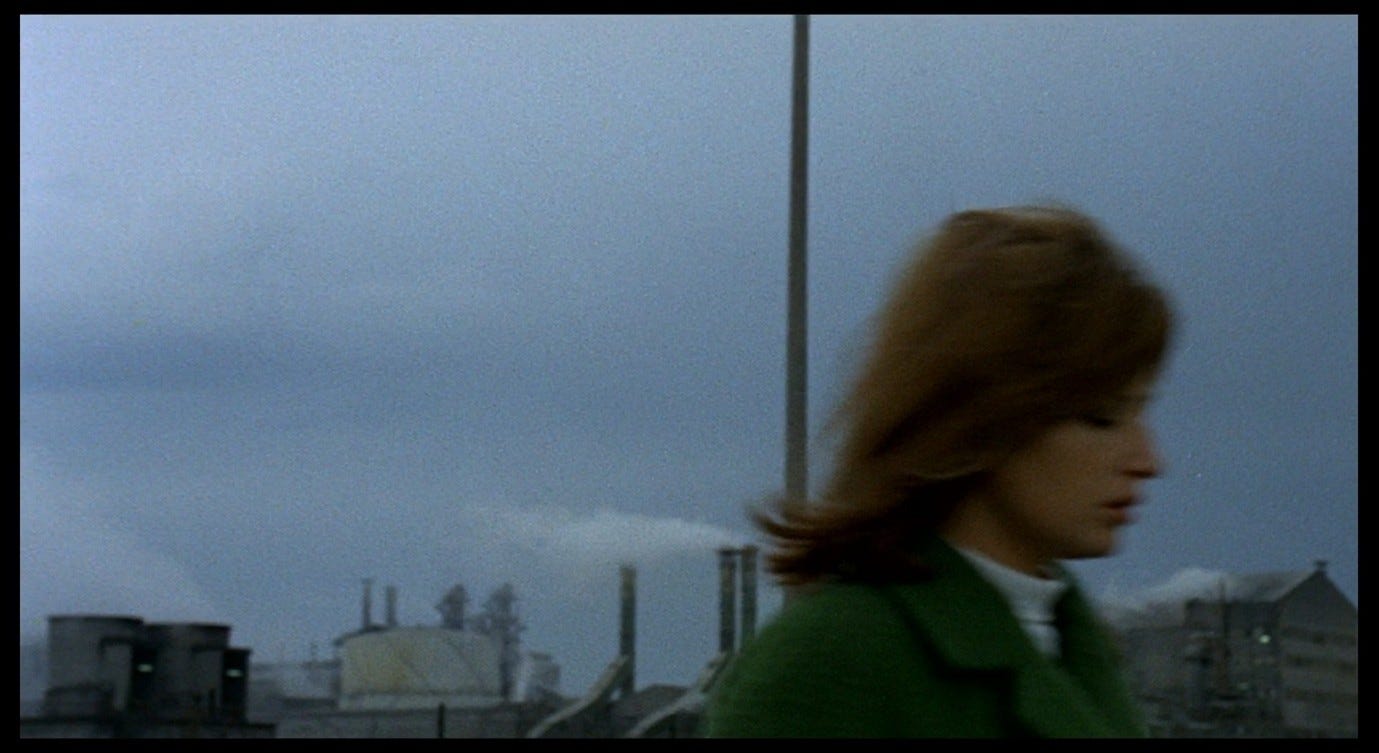

Unlike his mother, he does not stare at this phenomenon in terror with his arms dangling at his sides. He steps on the pipes, plays with the valve, and seeks to understand how and why they operate in the way they do. Moments later, he detaches from Giuliana again to explore another phenomenon. We see the two walking behind a wire-mesh fence, then Valerio drops his mother’s hand and runs ahead through an open gate. Giuliana looks around anxiously, reaching out as though to pull Valerio back, but we then see him in a close-up, staring fiercely at something in the distance. He has his own independent interests and refuses to be held back by Giuliana’s fears.

A wide shot reveals the enclosed courtyard in which these two are standing, but we are conscious of not being able to see what the characters see: they are looking off-camera at something behind us. This recalls Giuliana’s terror of off-screen phenomena in earlier scenes, and in this case especially we feel a kind of suspense about what these phenomena are. Why is this area closed off by a gate, why has that gate been left open, what does Valerio find so intriguing, and why is Giuliana so afraid of it?

In Stalker, when the three protagonists finally discover the wish-granting Room, they are able to see into it but we are not. Instead, we watch them looking at the Room and arguing about it, and we feel alarm when one of them almost stumbles inside.

Our (and the characters’) anticipation for this Room has been building throughout the film. The sight of it provokes such intense feelings in the people we are watching, and we want to see it for ourselves. The industrial compound in Red Desert does not have the mythological status of the Room, but in a way it has a similar significance. So much of this film is about Giuliana’s relationship with her environment, and especially with the industrial paraphernalia that surround her. In Stalker, the characters do not enter the Room that would grant their wishes; their journey is less about getting to this place than it is about coming to terms with themselves and the reality they live in. Do they know what their innermost desires are? Would they really want those desires to be fulfilled? What might that entail, in the ruined world they inhabit? There is, to paraphrase Giuliana, something terrible in themselves and in their world. To look into the Room – to stare into this abyss – is to become partially aware of that ‘terrible thing,’ and to step inside would bring full awareness.

When Tarkovsky finally places the camera inside the Room and dollies backwards to allow us to see the interior, the experience feels revelatory. There is something in this desolate, crumbling Room, and in the way the light interacts with the dripping and pooling water, that evokes the human condition.

Reversing Camus’s formula – of fictional characters ‘consummating’ what their creator cannot (see Part 49) – Tarkovsky enters the room and takes us with him, leaving his characters to watch from the safety of the threshold. What do we want or expect from a work of art, what parts of ourselves does it expose and/or fulfil, and how are we changed afterwards? This revelation is awe-inspiring, for better and for worse. It amazes us but is also amazingly mundane. It gives us what we want but also feels uncanny and unsafe. If Antonioni had used a similar technique at the end of Red Desert – dollying the camera backwards to show us, from the inside, the industrial compound the characters were looking at – he might have evoked something like this sense of awe, and prompted similar questions about what it means for us to be ‘among’ these phenomena while Giuliana and Valerio keep their distance. And he does in fact achieve some of these effects and prompt some of these questions, but in a way that differs significantly from Tarkovsky’s approach in Stalker.

Valerio points to the sky and asks another question. In a series of alternating close-ups of him and Giuliana, we get the final lines of dialogue in the film:

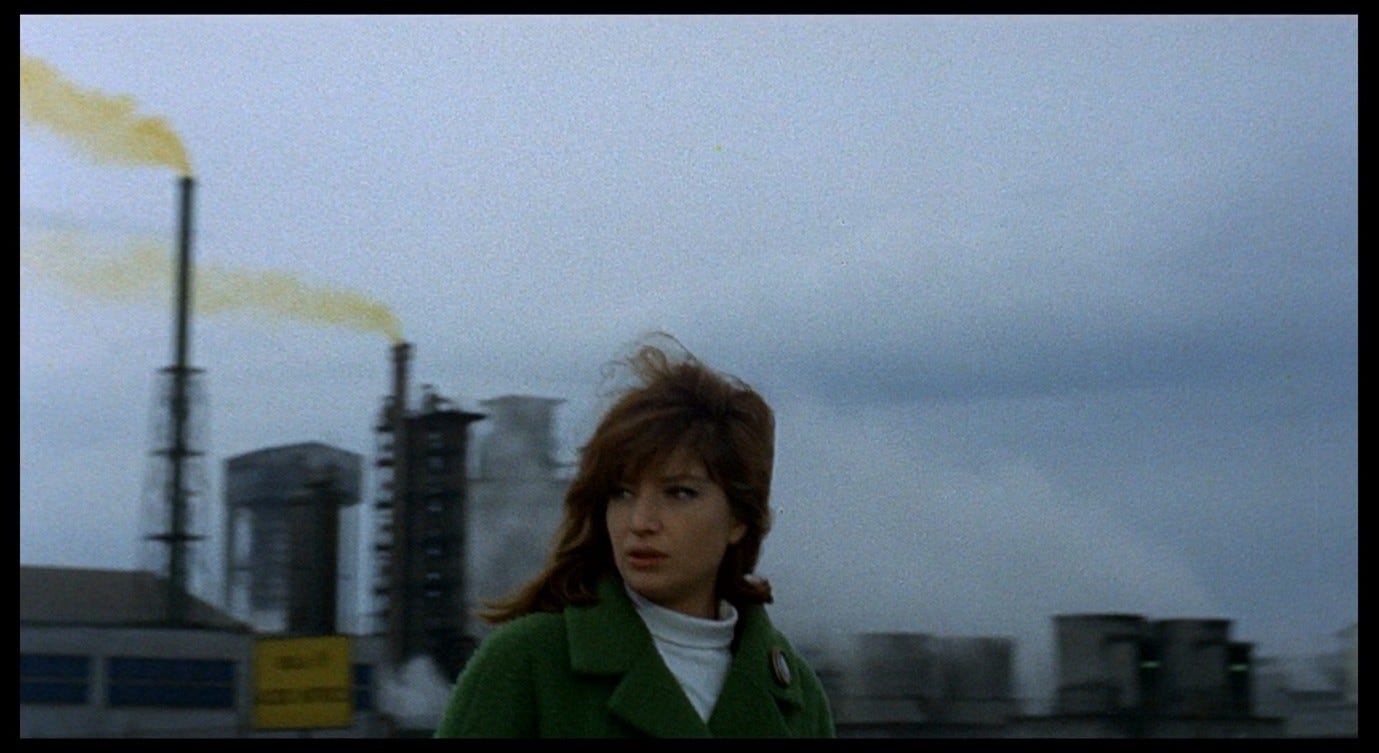

VALERIO: Why is that smoke yellow?

GIULIANA: Because there is poison in it.

VALERIO: Then, if a little bird [uccellino] flies through it, it will die.

GIULIANA: But now the little birds know that, and they no longer fly through it. Let’s go.

On the close-up of Valerio, we see Giuliana’s hand playing nervously with his, and her answers to his questions are bracketed by pauses. She blinks as she looks up at the yellow smoke. Throughout this sequence, the disconnect between the two characters is more than physical. Giuliana is lost in her own thoughts and feelings, which are quite separate from those of Valerio. Nothing about this exchange gives the impression of a meaningful dialogue between mother and son, or of an emotional bond that has been repaired since the paralysis hoax. Giuliana is still in the strange position of parenting a child who does not need her. If anything, as she told Corrado, she needs Valerio, but this need will of course go un-fulfilled.

Valerio’s second question refers to an uccellino – not just a bird, but a baby bird – and at first we might assume that, as a child, he identifies with this bird and its imperilled condition. But we can tell from the way Giuliana answers the question that she is thinking more of herself than of Valerio. She is the one who feels threatened by her environment and has had to learn to adapt. Indeed, Valerio’s question does not necessarily express concern for the little bird, but may simply be an observation: if the smoke is poisonous, it will kill any little birds that fly through it. So much for little birds. Perhaps Valerio does not want or need to hear the moral (‘Don’t fly through it’) that Giuliana provides; like his father, he is already comfortable navigating these industrial hazards.

The film pays no further attention to Valerio or to his perspective. He does not show relief that the little birds will be okay, or smile at his mother (or look at her at all, though she glances at him several times). As Giuliana leads him away from the compound, the camera stays with her, excluding him from the frame. At first, we see a low-angle shot of Giuliana beginning to walk away, and we glimpse some of the factory buildings (including the yellow smoke) in the far background.

Above the incessant humming of the factories, we hear the electronic robot-song from the title sequence. Then we cut to a very familiar type of composition: the frame is filled with colourful blurs, and the back of Giuliana’s head (when it enters the frame) is the only in-focus object.

She looks at the blurs for a few seconds as she walks slowly towards the open gateway. Then we cut to a panoramic wide shot of the whole compound, at last giving us a fully in-focus view of what the characters have been staring at. Giuliana turns her head quickly and walks towards the camera with Valerio, disappearing out of the bottom-right corner of the frame. The shot of the compound lingers for a few more seconds, then the film ends.

The final lines of the screenplay are as follows:

Giuliana turns and again sees the blotches [di nuovo vede le macchie] – hundreds of barrels lined up in the factory enclosure, like coloured blotches [come macchie colorate] – and hears the humming [ronzio] of the machines becoming sharp [acuto], sibilant. It is just a moment [attimo]. She quickly starts moving again, with her son, and leaves [scompare]. There remains the factory [Resta la fabbrica], with the chimneys, the white smoke, the yellow smoke, the steam, the barrels.1

The phrase di nuovo in the first sentence emphasises that these macchie are like the ones Giuliana has seen before: that is, they are like the phantom stains that spread over the wall and ceiling of Corrado’s hotel room, but also like the colourful blurs that ‘real’ people and objects turn into when Giuliana looks at them. The screenplay draws a connection between her blurred vision and the sharp, sibilant noises she hears. The heaps of barrels become like coloured blotches, the mechanical noises like singing robots. Giuliana’s perception works like Sabeth’s game of comparisons in Homo Faber (see Part 44), according to which nothing is simply itself, but must also be ‘like’ something else. For Walter Faber, this ultimately means that any surface in the world can become like the red desert he crash-landed in. Giuliana too is, in a sense, always in the red desert: at any moment, even if just for a moment (un attimo), that word ‘like [come]’ can transform her world, not distorting or falsifying it, but exposing the very real ‘terrible thing’ that lurks beneath the surface.

In this case, we see the terrible thing before we see the surface. The brief low-angle shot of Giuliana leaving the compound keeps the barrels out of frame, then we see them as Giuliana sees them (as a pink/yellow/blue blur), before the final shot reveals what this blur ‘really is,’ so to speak. The predominant colour is yellow and the blurring of the yellow-painted barrels associates them with the poisonous smoke. In the low-angle shot, we see Giuliana with her red hair blowing in the same direction as that smoke, passing just beneath it and away from it; then we see her facing a world that seems infused with yellow smoke.

As with earlier images of steam, smoke, or fog, we see an amorphous substance pervading reality until there is nothing left but that amorphous substance. There is something poisonous in this world, and it is spreading everywhere, to the point that there are few oases left – fewer places in which the birds can fly safely. In Albert Camus’s The Plague, the pestilence manifests itself not only in literal sickness but also in strange noises that fill the air, like the electronic whines that are a variation on the steam, smoke, and fog of Red Desert:

Out in the street it seemed to Rieux that the night was full of whispers. Somewhere in the black depths above the street-lamps there was a low soughing. […] Try as he might to shut his ears to it, he still was listening to that eerie sound above, the whispering of the plague […] Rieux was listening to the curious buzzing sound that was rising from the streets as if in answer to the soughings of the plague. At that moment he had a preternaturally vivid awareness of the town stretched out below, a victim world secluded and apart, and of the groans of agony stifled in its darkness.2

Rieux’s ‘preternaturally vivid awareness’ is akin to the awareness we attain in these final images of Red Desert, as we become attuned to the forces resonating within this ‘stretched out’ but ‘secluded’ place that Giuliana lives in. The blurred colours are like the whispers and eerie soughings that hint at some ‘agony stifled in darkness,’ and Giuliana possesses something like Rieux’s insight into these repressed realities.

The shot of the colourful blotches comes to rest on a long, light-blue blotch which, in this abstract painting we seem to inhabit for a moment, might be taken to represent the sky. But as we cut to the wide shot, we see that Giuliana’s eyeline is directed at a row of blue-painted surfaces (the sides of the barrels, arranged so as to obscure their yellow-painted ends), a mirage of blue in the sea of yellow.

The actual sky above the factories is as grey as the factories, and the clouds mingle with the smoke billowing from the chimneys. The earth below the yellow barrels seems to be turning yellow or brown, and as at the start of the film, Giuliana’s jacket is the greenest thing we can see. A yellow warning sign on the enclosure states that the barrels contain nitric acid, a substance dangerous enough to require a high level of containment, but also vital enough to be required in massive quantities – it is truly unsettling how much acid is on view in this single image. The camera is positioned facing the corner of the fenced-off enclosure, so that the fencing (and the barrels arranged behind it) seem to come to a point, pointing at us, heading in our direction. In the distance, the factory buildings encircle the other side of the compound, like an army of giants for which the barrels serve as the vanguard. It is both an image of an ‘entire world’ – an environment seen in the round – and an image of something that has expanded out to occupy the world, something that will continue to expand and advance. In Part 50, I noted the stark contrast between the blurred view of the factory towers in the first shot of the title sequence and the in-focus view of the same towers in the first shot of the final scene. The panoramic wide shot of the whole complex contains several other structures we saw in the title sequence: those nebulous, separated shapes from the start of the film are now revealed with a full and overwhelming clarity.

Like a bird fleeing from yellow smoke, Giuliana retreats from this menacing prospect, but we are left to contemplate it.

The word resta in that final line of the screenplay conveys a sense of what remains after the characters have disappeared, which is a very common dynamic in Antonioni’s endings. The story is over, the characters are gone…what are we left with? At the climax of Stalker, we and the characters are left to contemplate the nature of our own desires and our place in the world. If we decide not to enter the Room, what does that say about us, and what are we left with? If we do enter the Room (with the camera), what effect does it have on us – and again, what are we left with? At least one previous visitor to the Room took his own life, presumably because of what he discovered when his desires were granted. Giuliana too has been prompted to attempt suicide by – if we can sum it up like this – the problematic relation between her inner and outer reality. Like the characters in Stalker, she retreats, but her retreat may be futile: she is perhaps running from something inescapable, a Room that will soon swallow the entire world.

The economic boom, rapid technological advances, and rampant industrialisation portrayed in Red Desert are, in a sense, like the granting of wishes people seek out in the Room. The world desires growth and prosperity, and this desire is fulfilled. The question of ‘what remains’ after this – ‘E dopo?’ as Niccolò’s nephew says at the end of Identification of a Woman – can be asked on a number of different levels. If people like Giuliana are discarded while people like Ugo, Corrado, and Valerio thrive, what version of humanity are we left with? As for the world we live in, poisonous effluent has to go somewhere, so what will remain of the air, land, and water?

The Italian word FINE, which shoots towards us from the direction of the yellow barrels, has a special resonance when juxtaposed with refineries, and more broadly with an image that represents the point to which humanity has advanced.

We have refined our capacities and sifted out the parts of ourselves (and the members of our community, like Giuliana) that cannot keep up with these advances, and this is where we end up. Unlike in Stalker, the camera does not enter the space that has been charged with so much meaning by the characters who stare into it and talk about it. The viewer is left to contemplate this space from a distance. Do we see it as Giuliana does, or as Valerio does? Does the sky meld into the factories, then into the barrels, then into the fencing, then into the earth, then into the road, or do we see these as discrete layers that are easily distinguished from each other? Do we see these colours as they ‘really are,’ or do we see an amorphous red desert? Is there something terrible in this reality, or is it safe and mundane? Do we fly away in terror or are we in our element?

The eerie song of the robots seems to pause for a moment after Giuliana’s vision of the coloured blotches. When we cut to the wide shot, the multi-layered roaring and whining of the factories – the sounds that are ‘really there’ – rise in volume. Giuliana and Valerio disappear, and we still cannot hear the robots; they are not really there, so they only sing in Giuliana’s mind, just as the macchie she hallucinates only appear when we see the world through her eyes. The word FINE appears on the screen and stabilises. But then we hear the robot-song one last time, a series of ‘vworp’ sounds getting louder and more piercing, shimmering and echoing over the cut to black, before they are silenced once and for all.

This darkness is the real final image of Red Desert. When Giuliana hears the robots singing, as she looks fearfully at the colourful blotches, they seem to be telling her to get out, just as the yellow colouring in the smoke tells the birds to fly away. Left alone with the red desert, we see and hear as Giuliana did, and we too are chased into the darkness by those final notes of the song. ‘Get out and don’t come back.’

Some critics have interpreted this ending in more redemptive terms. William Arrowsmith reads the steam-vent imagery as indicating that Giuliana’s ‘psychic pressures are under control,’3 while Peter Brunette takes hope from the fact that ‘Giuliana is now actively taking care of her child’; this motherly behaviour indicates that ‘she has begun to overcome her neurosis.’4 The malattia depicted in this film needs to be controlled and moderated. It is a sickness insofar as it prevents Giuliana from performing her social role as a parent, and it can be overcome through balance and active (i.e. willing and enthusiastic) role-performing.

Christine Henderson likewise reads this as a moment of healing and a return to functionality:

Giuliana seems able to maintain a critical distance from her surroundings rather than being overwhelmed by them. She is able to interact in and with her world in a different way: as an individuated subject able to affirm her subjectivity and, to some extent, resist her conditions – that barrage of noises, colours, smells that once wore her down and utterly exhausted her sensory capacities. She maintains her ability to function, to act, to look after both her son and herself in the face of rapid transformations to both her landscape and her everyday life, in the midst of the passing of the old and the arrival of the unknown.5

Notice the ambiguity of Giuliana’s place in this scheme of recovery. She needs to be able to ‘maintain a critical distance from her surroundings,’ but how do you keep your distance from something that surrounds you? She needs to ‘interact in and with her world’: again, the world is both something she is in and something she interacts with; what does it mean to ‘interact in’ this space (i.e. interact with what or with whom)? She finds herself both ‘in the face of’ and ‘in the midst of’ larger forces that overwhelm her, wear her down, and exhaust her senses. They are rapid transformations, ‘the passing of the old and the arrival of the unknown’: significantly, Henderson does not say ‘the new,’ perhaps acknowledging that what arrives at the end of these transformations may be old and even archaic, but in any case ‘unknown’. Like Arrowsmith and Brunette, Henderson looks for a sense of equilibrium and a set of perform-able roles (‘to function, to act, to look after both her son and herself’) in this final tableau of Giuliana and the factories.

The ending of Red Desert is undeniably ambiguous, and I can see why people read it in these ways. But I think that Henderson’s portrait of the recovered (or at least convalescent) Giuliana is a vivid delineation of the malattia itself. Being an individuated subject, affirming one’s subjectivity, and resisting one’s conditions are all figured as prerequisites to recovery, but Henderson’s phrasing reminds us again and again that those conditions can only be resisted ‘to some extent,’ and that the distinctions between Giuliana and those conditions are constantly in flux. This is what I take from those two key statements, ‘There is something terrible in reality, and I don’t know what it is,’ and ‘Everything that happens to me is my life.’ Giuliana is alienated from her surroundings but unable to maintain a safe or critical distance from them, unable to prevent herself from being overwhelmed by them, and unable to interact with (or interact with others in) them in the ways that she is expected to. She is, after all, not looking after her son, because he is not in any danger. At this point, I do not even see her as being solicitous about him: she knows better than that since the paralysis hoax.

Henderson figures Giuliana as someone who is braced for ‘the arrival of the unknown’ and will now be able to deal with it, but I think what Giuliana has accepted is that she will very likely not be able to deal with it, and that whatever terrible thing happens to her next must simply be regarded as ‘her life’ – like Meursault’s execution in The Stranger, it might be the end of her life. ‘The future will probably present itself with a ruthlessness [ferocia] we can’t yet imagine,’ said Antonioni in Wim Wenders’ Room 666, and although he went on to say that ‘[m]y sense is: it won’t be all that hard to turn us [trasformare noi stessi] into new people,’6 there is a contradiction between the unforeseeable ferocia of what is heading our way and the alleged ease with which we will transform ourselves when it reaches us. Despite Antonioni’s pride in his own willingness to adapt to changing circumstances, I think he knows that he is more like Giuliana than he is like Valerio, and that he will not be among those new people ‘we’ will transform ourselves into.

At stake here is the question, to which I have returned many times throughout this series, of how Giuliana is situated in relation to Antonioni, the camera, and the audience. Put simply, is the film on her side or not? Does it ask us to empathise with her or (to use Henderson’s phrase) maintain a critical distance from her?

Millicent Marcus sees Red Desert as a kind of origin story for Antonioni’s artistic practice:

If Giuliana’s abstracting vision is equivalent to Antonioni’s, then her story is an explanation, though in no literal-minded way, of how his own visual style came to be. By grounding his vision in a character who has a tendency to look with wonder and fear at the things around her, Antonioni suggests a prior phase of his own perceptual development. What Giuliana accomplishes in Red Desert by transforming her fear of the world abstractly perceived into an acceptance of it, is a prerequisite to the artist’s own accomplishment, which is to transform that acceptance into a celebration. By the end of the film, Giuliana is not quite at the point where Antonioni is at the beginning – she has learned to fly around the poisonous yellow smoke but has not yet learned to love its yellowness, or its texture or shape. Presumably, this too will come, now that she has abandoned her dreams of escape, be they through suicide, adultery, stowing away, or selling undetermined merchandise in a multicolored shop, and can now concentrate on putting her abstract vision to positive uses.7

Again, Giuliana is said to have accomplished something by the end of the film, by transforming her fear of the world into an acceptance of it. Here, though, the end-goal is not exactly psychological recovery or wellness, but the ‘positive uses’ of art, the celebration of that fearful and wonderful red desert in which we find ourselves. Where Pasolini saw Giuliana’s and Antonioni’s perspectives as being inextricably mingled (see Part 29), Marcus sees Giuliana as representing a ‘prior phase’ in Antonioni’s perceptual development. We are, so to speak, seeing the artwork she will one day create, in which she portrays her journey towards ‘accepting’ the red desert, and thereby goes a step further and ‘celebrates’ it as well. Her act of celebration could not be portrayed in the film, as it is constituted by the making of the film.

Why is transforming fear into acceptance a ‘prerequisite to the artist’s own accomplishment’? Clearly, Antonioni was capable of celebrating the beauty of the industrial landscape that so terrifies Giuliana (see Part 5), but I think Red Desert is also predicated on the idea that the artist must not let go of that fear, must not discard it as a ‘prior phase of perceptual development.’ Arguably, what the film accepts and celebrates is Giuliana’s perspective, for all that it is ‘neurotic’ and for all that she refuses to love that poisonous smoke for its yellowness, texture, or shape. Is this a prior phase of perceptual development, or a present one that has been repressed?

Behind all the above-quoted readings of Red Desert’s ending, I sense an urge to control and moderate the film’s more disturbing implications. To live without equilibrium, to be an unloved and unloving mother, to be at odds with a reality from which we nonetheless cannot escape – the ‘positive use’ of art is to resolve, somehow, these intolerable states of being. Both those words, ‘positive’ and ‘use’, come with a lot of baggage, and I think it is worth putting them to one side and forgetting, for a moment, about what is positive and what is useful. Red Desert expresses those intolerable states of being, whether or not it is positive or useful to do so. Giuliana survives but has not achieved equilibrium. Her relationship with Valerio (and everyone else) is still broken. And when she looks at that yellow smoke, she is not just unable to celebrate it – she does not accept it, she remains at odds with it, and it remains inescapable.

In a scripted but un-filmed scene from This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection, when asked ‘What do you see?’, Mantoa was to look into the horizon and say, ‘I see the red dust.’ Lemohang Mosese explains, in his commentary track, that this was a reference to the ‘red dust’ drought in Lesotho in 1933, and that the phrase has come to refer more generally to a time of approaching famine or tribulation.8 In literal terms, Mantoa’s village is about to be drowned and turned into a reservoir, but for her this represents a metaphorical drought, a red-desert-ification of her ancestral home by the forces of modern industry. She has a place in Nazaretha: her friends and family are buried in this ground and she insists on being buried there as well. But her resistance to the future sets her at odds with this place, or rather with the place Nazaretha is becoming. Her home is burnt down, and in the end – like Massimo Girotti in the final scene of Theorem – she strips naked and strides, with her back to the camera, towards annihilation. She cannot overcome the red dust, but she refuses to accept it. In the last shot of the film, a young girl looks into the camera while the narrator says:

Many saw death, but Ke’moralioamang, Daughter of No One, saw a resurrection. It wasn’t for the dead, but for the living.

Mosese’s previous film, Mother, I Am Suffocating. This Is My Last Film About You, could be seen as picking up where This Is Not a Burial ends, because it is set in the version of Lesotho that Mantoa sees blowing towards her in the red dust, and it is narrated by someone like the Daughter of No One. ‘This is the last time my feet will ever touch this dusty red soil,’ she says to her motherland, Lesotho, vowing to abandon this country for good. Much of the film plays out in a street known locally as ‘the dust’, and A. E. Hunt suggests that Mosese may have chosen this setting ‘because it is a transient space akin to his own sense of displacement.’9 As Mosese said in an interview:

I belong to Lesotho and yet I am not a part of it. I am spaceless. I create better from this formless state because I can see better as an outsider. Creating art from this state of mind is rewarding but it has made me a lost person. I wouldn’t have been able to see my country or Africa as a whole if I was inside it.10

Both these films derive their power from this spaceless, formless state, this sense of being a ‘lost person,’ and from Mosese’s unflinching commitment to expressing this condition. Mother, I Am Suffocating also ends with a child looking into the camera lens. Their head has been wrapped in wool, obscuring and blurring their vision, but now the wool has been unravelled and they stare at us.

The narrator addresses Mother-Lesotho: ‘I’ve been standing here for an hour staring into the mirror. Do you know what I see, mother? I see you.’ To live in Lesotho means being wrapped, imprisoned, and blinded in a fabric woven by others, but to remove that fabric and finally look into the mirror is to see Lesotho staring back at you. So much for being an individuated subject and affirming your own subjectivity, and so much for relating to your environment in a coherent, functional way. Mosese, unlike Giuliana, left his country and re-located to Berlin, but however far he travels it will never be the last time his feet touch that dusty red soil, and he will never make his last film about Lesotho. He belongs to it and yet he is not a part of it; as a ‘lost person,’ he has no self to see in the mirror, only a reflection of the red dust to which he belongs. Paradoxically, it is because he leans into this ‘formless state’ that he is able to ‘see better’ and create such singular, personal works of art.

Red Desert challenges us not to look for a way out, but to stare with wide-open eyes at that final image of the factory complex, and to grasp this ‘terrible thing in reality’ as completely as we can. If, instead of saying that Giuliana finds balance and repairs her relationships and has a place in the world, we say that she is just as spaceless and stateless and ‘without qualities’ as she was at the start of the film, we will see something important. Why is the sight of Mantoa being gunned down ‘not a burial, but a resurrection,’ and in what sense is it ‘for the living’? I think Mosese answers these questions when he says that he can ‘create better’ and ‘see better’ and that he ‘wouldn’t have been able to see’ without that feeling of non-belonging. Connecting with Giuliana’s despair revives something in us, or un-buries and un-represses it; imposing redemption on her is a burial.

Next: Part 52, Seen enough today.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 497

Camus, Albert, The Plague (1947), trans. Stuart Gilbert (Tingle Books, 2021), pp. 96-99 (Kindle edition)

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 104

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 107

Henderson, Christine, ‘The Trials of Individuation in Late Modernity: Exploring Subject Formation in Antonioni’s Red Desert’, Film-Philosophy 15 (2011), pp. 161-178; p. 176

The text of Antonioni’s speech is reproduced in Wenders, Wim, My Time with Antonioni, trans. Michael Hofmann (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), p. x. The first statement, in Italian, is ‘È molto probabile che il futuro si presenti con una ferocia che al giorno d’oggi non c’è ancora, per quanto si già si può presentare quello che sarà,’ which literally translates as ‘It is very likely that the future will present itself with a ferocity that is not yet there today, however much one can already present what will be.’ Hofmann’s translation conveys Antonioni’s meaning, but the hedging and uncertainty of the original are significant in the context of this discussion.

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), pp. 193-194

Mosese, Lemohang Jeremiah, and Cait Pansegrouw, Commentary track, This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Blu-ray, Criterion 2023)

Hunt, A. E., ‘Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese: Contours in the Dust’, mubi.com, 13 January 2021

Vourlias, Christopher, ‘Director Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese: Africa Is “In the Process of Becoming”’, Variety, 02 December 2019