Everything That Happens in Red Desert (18)

The daytrip gone wrong

By this point in Red Desert, all of the ‘setting up’ has been completed. We understand the world in which the action takes place – the industrial landscape and its processes – and we understand that the action centres upon the parallel development of Giuliana’s affair with Corrado and her mental health crisis. The film now indulges in a long set-piece in which the characters are left to interact in a kind of vacuum, with no motivation aside from getting together and having fun. Parts 18-22 in this series will focus on this 30-minute sequence at the centre of Red Desert, in which the main characters go on a daytrip that ends with Giuliana almost driving into the sea.

Such set-pieces are common in Antonioni’s films. Having introduced his characters, he often sends them on a leisure trip to the countryside or seaside, or to a party, and observes their behaviour while they are trying to be at ease. This interest in the leisure activities of the leisured classes relates to the ‘problem of the bicycle’ which I discussed in Part 16. In the context of the economic boom of the 1950s and 60s, it is (Antonioni argues) important to make films about the inner states of economically secure people who have a lot of time on their hands, as they look for something to do with that time and with each other.

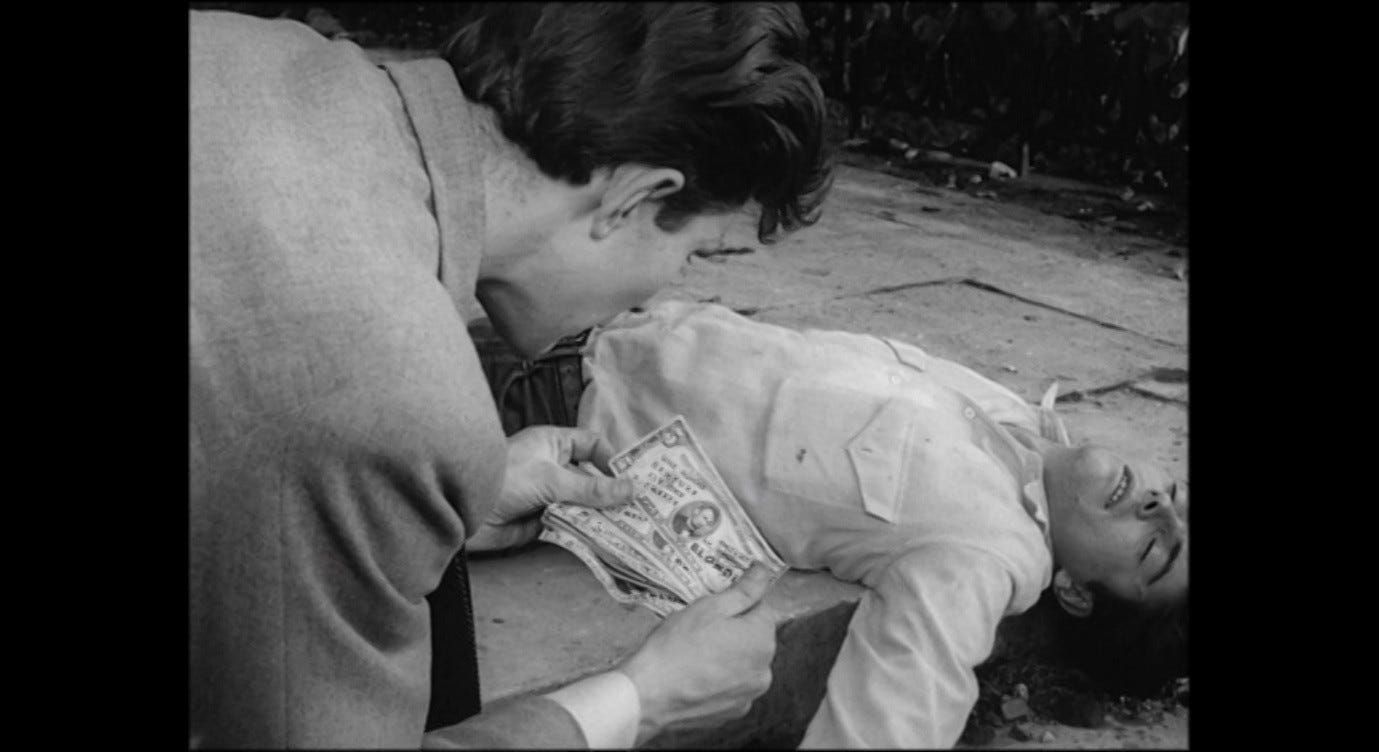

At some point in the Antonioni daytrip, something always goes wrong, sometimes very wrong indeed. In the French episode of I vinti, some teenagers take their seemingly rich friend into the countryside in order to murder him and steal his cash. Their plan is to then travel abroad and build a new, more exciting life for themselves. The rich boy, as it turns out, is not rich at all. He has been spinning a fantasy to make himself more interesting and his friends have become tragically caught up in this vision of the jet-setting playboy lifestyle. The episode establishes several motifs that will recur in later films: desultory meandering through a natural landscape, tensions (sexual and otherwise) that simmer to a breaking point, and a threat of betrayal (tangled up with a misunderstanding) hanging in the air.

In the trip to the beach in Le amiche, the trip to Lisca Bianca in L’avventura, or the party scenes in both those films and La notte, we see clearer precedents for the outing in Red Desert. The teenagers of I vinti have now grown into bored, disillusioned adults, and the new tensions and betrayals are even less rooted in material needs, more concerned with emotional stakes.

In Le amiche, leisure time allows the characters to stand back from their immediate problems and to ask one of the central questions of the film: does anyone really need or care about Rosetta? Her recent suicide attempt is all her friends are talking about, but it makes them nervous to interact with her. She reluctantly accompanies them to the beach and, un-protected by the walls that normally contain this ‘elephant in the room’, overhears a cruel joke at her expense. Seymour Chatman describes the scene:

The beach, sky, and water provide a vast arena within which the characters can at once disport and reveal themselves. The empty ambience nakedly demonstrates the power of the little clique both to embrace and to ostracize. As Mariella callously remarks that Rosetta might as well kill herself since she does not have a man, the group parts to form a kind of aisle or passageway through which Rosetta passes, uncomforted in her despair. The beach offers no resistance to cruelty: its very openness facilitates the creation of this parody of a wedding archway.1

From Rosetta’s point of view, however, Mariella’s joke is preferable to Momina’s more insidious cruelty. The joke is a violation of decorum, an attempt to relieve the pressure everyone feels, and it comments on an aspect of the ‘social ambience’ within which these people live. As Chatman suggests, the scene is about people ‘disporting and revealing themselves,’ playing the games that define their ‘little clique’ but also exposing the rules of those games. It is as though Mariella were saying, as a joke at her friends’ expense as much as Rosetta’s, ‘We are going to kill Rosetta for her failure-in-love, aren’t we?’ Momina, who will be held partially responsible for Rosetta’s death (Clelia calls her an assassina) is angry because this ugly truth should not be spoken out loud.

Matilde Nardelli reads these social dynamics in terms not only of leisure but of boredom:

The epidemic, democratic and ‘levelling’ aspect of boredom is important in Antonioni’s recurrent thematisation of the phenomenon. In […] Le amiche (1955), boredom seems only to affect the upper middle classes; well-off, non-working women especially. Clelia, the working woman protagonist busy setting up a fashion salon in Turin, has no time for it, as she herself explains.2

This highlights a kind of paradox: when these people focus intensively on enjoying themselves, they realise how incapable they are of doing so. If Rosetta did not have the luxury of going on daytrips and dining out with her friends – if she were able to commit to the job Clelia offers her after the incident on the beach – she would not have time for the leisure that leads to boredom that leads to suicidal depression. It is significant that Rosetta’s suicide is finally triggered by Lorenzo telling her he does not need her: ‘The truth is,’ he says hesitantly, ‘I don’t need anyone.’ Not having needs is, in a way, the definition of leisure; it is like the beach, a vast emptiness that could (terrifyingly) be filled up with anything at all, or in Lorenzo’s case with nothing.

By the same token, Clelia’s dedication to her work is not exactly her ‘salvation’, rather it enables her to remain in denial about the bleak, friendless life she leads. Her time is filled up with ‘needs’, with the things she requires of her employees and the things her employers require of her. This is where the ‘levelling’ effect of boredom (referred to by Nardelli) comes into play: Clelia’s time ‘on the beach’, amidst the yawning emptiness of these rich amiche, brings her into contact with Rosetta’s boredom and depression, perhaps infecting her with it in a way that will stay with her after she returns to Rome. In that sense, she is a precursor to Claudia in L’avventura and Corrado in Red Desert, taking a kind of holiday in other people’s lives and finding herself irreparably changed by it.

In L’avventura, it is the act of spending leisure time together that exposes the emptiness of Sandro’s relationship with Anna. Like Mariella, she is not afraid to say aloud how bored she is (‘Uffa che noia!’). When she says to Sandro, ‘I don’t feel you anymore,’ this echoes Lorenzo’s ‘I don’t need anyone,’ in that it makes visible the empty space between them – the space of leisure and boredom that must be filled by arbitrary things, and therefore can be filled by anything or nothing. When Anna vanishes, the way in which Claudia arbitrarily takes her place exposes the emptiness of that connection in turn. ‘It’s sad,’ says Claudia, ‘I’m not used to it.’

She then turns out to be interchangeable with yet another woman at the end of the film, when Sandro cheats on her. Left on his own, at leisure in the aftermath of the party, what else was Sandro going to do?

La notte revolves around a single night in which a woman gradually realises there is no love between her and her husband. As they sit together in a nightclub watching a show, Lidia playfully mimes the arrival of this realisation in her head, as though it were something amusing.

Only much later, when she tells Giovanni what the realisation was, do we understand how high the stakes were in that moment of seemingly inconsequential play.

An important motif that recurs throughout these sequences is the disparity between the characters. This is often figured in terms of class or wealth – the poor kids envying the rich kid, Clelia marvelling at the decadence of Turin’s upper crust, Claudia commenting on her ‘very sensible’ (meaning ‘poor’) upbringing as she learns the ways of her new and wealthy friends, Lidia and Giovanni coming to terms with their entry into a higher stratum of Milanese society.

In La notte, Monica Vitti is given a secondary role as Valentina, an industrialist’s daughter who (unlike Claudia in L’avventura) has grown up in conditions of extreme wealth and is now undergoing a low-key existential crisis. She kills time by inventing games, reading difficult novels, recording and then deleting her anxious musings on life, and flirting with the couple who drift into her cold, opulent home. Her encounter with their marital crisis exhausts her, and she withdraws into dark solitude at the end of the film.

The things that made Claudia ‘sad,’ that she was ‘not used to,’ do not seem to faze Valentina – she is used to them – but their effect has deepened into a depressive cynicism. The cool shadow in which she envelops herself is this film’s equivalent of Rosetta’s suicide. Valentina does not take her own life, she just takes herself out of the light, vanishing into her own notte as the sun rises outside.

Giuliana in Red Desert seems to have gone a step further. There is no longer any discernible class distinction between her and the other characters – they all occupy the same sphere – but the sense of dislocation is more profound than ever. This is part of what motivated Pauline Kael’s famously negative review of Red Desert: she is frustrated at having to spend so much time spectating the problems of this bored, leisured housewife. Kael describes a woman she once met who resembles Giuliana:

[S]he couldn’t think of anything to do with her life so she did nothing for herself, her husband, or anyone else – and made herself ‘interesting’ by her desolation. Is she fascinating? Well in a way, if you like to observe this kind of post-analytic destroyed consciousness. These ladies […] are taken care of and give nothing […] presumably because they’re so sensitive, so vulnerable. But, of course who with money and nothing to do can’t be sensitive and vulnerable? They’re not vulnerable to what the rest of us are; they’re indifferent to all that. At worst, they’re patronizingly envious of us – of our exhausting jobs, our household chores, our struggle to find time to read and see and think. […] Knowing there are people like this, I can understand that The Red Desert relates to something. But the title and Ravenna and industrialism, that’s all a red herring. And so, I think, is the use of color in the movie. The bored, indolent ladies of Beverly Hills and elsewhere are much more likely to feel that their clothes have suddenly gone gray and to rush out to buy others. Their lovers go gray, too, and they try on others. Despite this relationship to the world around us, I found the movie deadly: a hazy poetic illustration of emotional chaos – which was made peculiarly attractive. […] Those who loved the movie, the TV producers’ and architects’ wives who feel that their lives are wasted and who are too ‘gifted’ to do good, useful work, were likely to say things like, ‘I loved looking at it, I didn’t care what the content was,’ which probably means not just that they found it visually pleasurable but that they enjoyed drifting away into vague, stylish emotional states – which is about the only way one can respond to the frozen rhythms. I think they thought it was the story of their lives: they identified with that crazy sensitive broad. […] And as reacting to the movie meant for these women not an interpretation which could be validated by checking it against the meanings and connections in the work, but anything that happened to occur to them as they saw it or thought about it afterward, they didn’t necessarily care that it didn’t make sense.3

There is a lot to unpack here. First, it is important to note that Red Desert is, on one level, about this leisured-class ennui; ‘Knowing there are people like this,’ Kael says, ‘I can understand that The Red Desert relates to something.’ A few lines earlier, she acknowledges ‘this relationship to the world around us,’ meaning that what we see in the film relates to something in our world. And yet ‘despite this,’ Kael hates the film; despite her repeated concession that it relates to ‘something,’ her critique rests on the repeated claim that it does not. People who like Red Desert ‘don’t care what the content is.’ Their interpretations are not ‘checked against’ (i.e. related to) the film itself, but simply reflect ‘anything that happened to occur to them.’ ‘Everything that happens to me is my life,’ says Giuliana, but anything that ‘happens to occur’ to a viewer of Red Desert is not really related to the film, it’s just in your own head. The film, Kael affirms, ‘didn’t make sense.’ To ‘drift away into vague, stylish emotional states’ is ‘about the only way one can respond.’ The word ‘about’ is a kind of mumbled admission that there are (of course) other ways to respond to this film.

Critiques like this are frustrating because they function by closing down possible lines of thought or analysis, thereby absolving the critic from having to explore their reasons for disliking something. Nonetheless, I think it is worth trying to disentangle some of Kael’s reasons, and that doing so will help to illuminate some important functions of Red Desert’s daytrip sequence.

First of all, Kael’s ire is directed primarily at women: not directly at Giuliana herself, but at the women (TV producers’ and architects’ wives) who identify with her. The problem clearly is Giuliana, but it has to be displaced onto a whole set of other women, and they have to be paper-thin stereotypes to serve their designated function. Insofar as Kael begins to articulate what the film might be about, she does so in terms of bored rich women who kid themselves into thinking it is their clothes and lovers – not themselves – that have gone grey. This, I think, is something like the film Kael wanted Red Desert to be, if only because it would have been easier to review (negatively). A few years earlier, when she championed L’avventura, Kael seemed to enjoy it as a satire on people who are ‘passive as if post-analytic’ and ‘too shallow to be truly lonely’:

Perhaps compassion is reserved for the lives of the poor: […] the intransigeance of defeated man is noble in Umberto D. […] But modern artists cannot view themselves (or us) tragically: rightly or wrongly, we feel that we defeat ourselves. […] Antonioni is an avowed Marxist – but from this film I think we can say that although he may believe in the socialist criticism of society, he has no faith in the socialist solution. When you think it over, probably more of us than would care to admit it feel the same way.4

This strikes me as a mis-reading of L’avventura. I do not know why Kael sees those characters as beyond the reach of compassion, or beyond the capacity for loneliness; indeed, I do not know what it means to be ‘too shallow to be truly lonely,’ and I am tempted to see this as an under-analysed comment from someone who is too shallow (or in too shallow a mood) to understand loneliness. In Kael’s ostensibly positive reaction to L’avventura, we can see the roots of her scathing review of La notte the following year:

There is a glamour that [Antonioni’s] characters seem to find in their own desolation and emptiness, and I think to an American art-house audience this glamorous world-weariness looks very elegant indeed. How exquisitely bored and decadent are the Antonioni figures, moving through their spiritual wasteland, how fashionable is their despair. The images are emptied of meaning. […] In La Notte we see people for whom life has lost all meaning, but we are given no insight into why. They’re so damned inert about their situation that I wind up wanting to throw stones at people who live in glass houses. […] They are the post-analytic set. […] Fellini [in La dolce vita] and Antonioni ask us to share their moral disgust at the life they show us – as if they were illuminating our lives, but are they? Nothing seems more self-indulgent and shallow than the dissatisfaction of the enervated rich; nothing is easier to attack or expose. […] I don’t understand how these film artists can think they are analyzing or demonstrating their own – that is to say, our own, emptiness by showing the rich failing to enjoy a big party. […] I suspect many Americans are attracted by this view of fabulous parties, jaded people, baroque palaces; to an American who works damned hard, old-world decadence doesn’t look so bad. […] Forgive me if I sound plaintive: I’ve never been to one of these dreadfully decadent big parties (the people I know are more likely to give bring-your-own-bottle parties). And isn’t it likely that these directors, disgusted though they may be, also love the spectacle of wealth and idleness, or why do they concentrate on these so empty and desiccated rich types? If the malaise is general, why single out the rich for condemnation? If the malaise affects only the rich, is it so very important? As usual, there is a false note in the moralist’s voice.5

Perhaps it is worth saying that I do not go to any parties of any kind, and that I have no fashion sense whatsoever. I would experience these parties and daytrips as unendurable nightmares. Old-world decadence does look so bad to me, though not in a moral sense. Morality is, I think, a key problem here: Kael despises these rich people and wants to see them satirised, and somehow L’avventura met that desire; but by the time she watches La notte and especially Red Desert, she finds this approach untenable. The reviews become tangled up in a series of questions. Isn’t Antonioni condemning these people? And yet isn’t that a bit facile? And yet doesn’t it seem ‘likely’ that he loves them as well, since he looks at them so intensely? It is incoherent to accuse a film of being a facile take-down of its characters, then accuse it of taking them too seriously. It is this same unwillingness to think beyond such limiting preconceptions (about deserving objects of satire and deserving subjects of serious drama) that leads to Kael’s protests over Red Desert’s supposed meaninglessness. If Giuliana is not a spoilt rich housewife deluding herself into thinking her world has gone grey, then what else can she possibly be?

Antonioni empathises with his characters and wants to make us empathise with them as well, and I think this is what Kael struggles to come to terms with when she asks what Antonioni is trying to say about himself and about us. For instance, when she says that nothing is more self-indulgent and shallow than the enervation of the rich, and that nothing is easier to attack or expose, she is clashing with La notte’s fundamental claim: that these people’s malaise is real and profound, and that it is not at all easy to express or illuminate. This was Antonioni’s point about the ‘problem of the bicycle’ (see Part 16). No doubt there is a difference between de Sica’s sympathy for Antonio or Umberto D. and Antonioni’s empathy for Lidia or Giuliana, but if you think that one set of characters deserves compassion and the other does not, you will not be able to connect with Antonioni’s films, and they will indeed seem empty to you.

Throughout the reviews quoted above, there is a common thread of self-inflicted misery: ‘rightly or wrongly, we feel that we defeat ourselves,’ says Kael (admiringly) of L’avventura, explaining why the film is not tragic. Again, I do not understand the limits being drawn here – why is self-defeat not tragic? – but I also think that L’avventura is about people whose self-defeat is situated within (and in some ways caused by) a wider set of circumstances, not about morality-play characters who bring ruin on themselves. When we get to La notte and Red Desert, Kael formulates this in different terms: Antonioni claims to hate this party but really he loves it; Giuliana is only miserable because she wants to be; the housewives who rave about these films are just posing as alienated because this is a fashionable emotion. Leisure activities – parties or daytrips – are potent symbols for this kind of self-inflicted malaise. All those Antonioni clichés, all that ennui and despair and incommunicability, it’s all just a fashionable party for a bunch of self-absorbed rich people. It is indeed hard to blame Kael for failing to care about such people in the way that she cared about the tragic heroes of late-40s/early-50s neorealist films. If you do not have it in you to feel compassion for the likes of Giuliana, especially when you are being told that her pain is at its most acute during her times of leisure, that is of course fair enough.

However, there is another common thread in Kael’s Antonioni reviews that is more problematic. In relation to L’avventura, La notte, and Red Desert, she refers to the characters as ‘post-analytic’ and associates this post-analytic state with passivity, emptiness, and ‘destroyed consciousness.’ This dovetails with her own refusal to analyse the films; these reviews are post-analytic in the sense that they bypass and dismiss the possibility of analysis. Kael refuses to see what is in Red Desert and then complains that it is empty; she does not know what the title or the images of factories mean so she declares them ‘red herrings’; for reasons she cannot share, she finds Giuliana contemptible, so rather than talk about her she targets the kind of people who are (as Kael says in her review of La notte) depressingly easy targets, stupid rich old American women whom most readers can be relied upon to despise. But Giuliana is a young, Italian, middle-class engineer’s wife who is suicidally depressed because of a problem in her sense of attachment to her self, to others, and to the world. Why not state that very obvious fact about Red Desert, rather than talking about greying Beverly Hills narcissists, and then explain why this woman is so objectionable?

In her review of La notte, Kael says that people who find the film beautiful sound ‘as weak and empty as the people in the movie,’ which raises questions about what makes a person sound weak (as opposed to strong) and empty (as opposed to full). But Kael adds a footnote:

Even while I was saying these words on the radio, I was aware that they weren’t adequate, that I was somehow dodging the issue. Though I believe that whatever moves people is important, I am, perhaps by temperament, unable to understand or sympathize with those who are drawn to the La Notte view of life.6

For me, this footnote is the strongest, fullest part of Kael’s Antonioni reviews. To say, ‘I despise this person but I don’t know why,’ is like saying, ‘There is something terrible in reality, and I don’t know what it is.’ For a moment, Kael sounds like an Antonioni character – like Clelia struggling to understand Rosetta’s depression and suicide, blaming Momina but knowing somehow that this is not ‘adequate,’ that it is ‘dodging the issue.’ It is also striking that Kael added this footnote (which was not in the original text) after reading this piece out on the radio: hearing herself dismissing those weak, empty people who liked La notte makes her feel displaced from that speaking self, conscious that her words are evading her feelings. Most remarkable of all is the admission of incoherence: the belief that ‘whatever moves people is important’ clashes with Kael’s inability to acknowledge the importance of whatever moves these Antonioni fans.

The La notte footnote foreshadows the core tension in the Red Desert review, between the sense that the film is about something and the sense that it is about nothing. There is something on the other side of ‘analysis’ that Kael is ‘unable to understand’ or is ‘dodging.’ In a shorter review of Red Desert, Kael summed it up as ‘Boredom in Ravenna, and it seeps into the viewer’s bones.’7 Before I saw Red Desert – when reviews like this were still putting me off watching any Antonioni films – I thought this was a funny put-down, but after seeing the film it reads very differently. The feeling Kael describes, of the film’s mood gradually taking over the viewer’s, is one of the things I most value about Red Desert, and in a way I think she is trying to be fair to Antonioni’s fans, to people who enjoy the sensation of boredom ‘seeping into their bones.’ But again, the word ‘enjoy’ is problematic for Kael. The capsule review goes on:

Antonioni’s hazy illustration of emotional chaos may or may not have something to do with industrialism; he makes the hazy, polluted atmosphere so ethereal that one can’t decide.8

The comment about ‘ethereality’ echoes the comment in the longer review about the ‘emotional chaos’ in Red Desert being ‘peculiarly attractive.’ The slippage between ‘attractive’ and ‘ethereal’ (with a repetition of ‘hazy’ mixed in) is significant: the film’s treatment of mental illness is disingenuous because it makes depression seem so attractive; what people like about the film is ‘ethereal’ and ‘hazy’, meaning that it is vague to the point of not really existing; the truth is that Red Desert is just a really boring film about boredom, and what is the point in that?

Antonioni’s daytrips are like his desert spaces. On the one hand, emptiness and leisure can be conducive to communication and understanding, as Clara hoped when she took Nardo into that wasteland outside Rome (see Part 12). On the other hand, they can just as easily be spaces in which people lapse back into their automatic, customary behaviours, like Nardo spouting his tired romantic clichés, failing to hear Clara or to express himself adequately. A film review is a similar kind of empty space. The critic can say anything at all: they can earnestly relate their own feelings to those being expressed in the film, or they can ignore both sets of emotions and fall back on familiar conventions. As Kael says, ‘there is a false note in the moralist’s voice;’ unsure of how to listen or speak to Red Desert, she transforms it into an easy target and throws facile insults at it. But there is a false note here: she does not really have a problem with spoilt rich people, but with weak empty ones, and even then (as Kael herself says) the problem is not really that they are weak and empty. So what is the problem?

Spending time with Ugo, Corrado, and her other ‘friends’, Giuliana is confronted with a microcosm of her life and her world, and being at leisure she has nothing to do but reflect on the meaning of this increasingly nightmarish spectacle. Like the characters in the earlier films, she realises something – about her attachments, about her environment, about her future – that makes her want to drown or disappear or somehow escape. Over the next few weeks, we will see echoes of Pauline Kael’s post-analytic take on these issues: Giuliana will encounter a similar kind of impatience, a similar reluctance (on the part of others) to see or hear what she is seeing and hearing. But we, as viewers, will come closer to being able to answer that overwhelming question at the end of the previous paragraph.

Besides leisure and boredom (and closely connected to them), escape is one of the overarching principles of the daytrip sequence in Red Desert. Chatman, noting that the theme of escape ‘appears in some form in virtually every one of Antonioni’s films,’ calls the films’ characters ‘conscious or unconscious escapists, running away from rather than facing up to their problems.’9 The initial motivation for the outing in Red Desert is to escape from the city to a nice fishing spot in the countryside, but the fishing spot turns out to have been ruined by effluent from the factories. The characters then escape from the polluted countryside to a pier that extends far into the ocean, far enough so that the water is clean and the fish edible. But then a ship arrives carrying an unknown disease, and the characters escape again – only for Giuliana to drive back towards the infected vessel, and towards the sea beyond it, seeking a different and more permanent kind of escape.

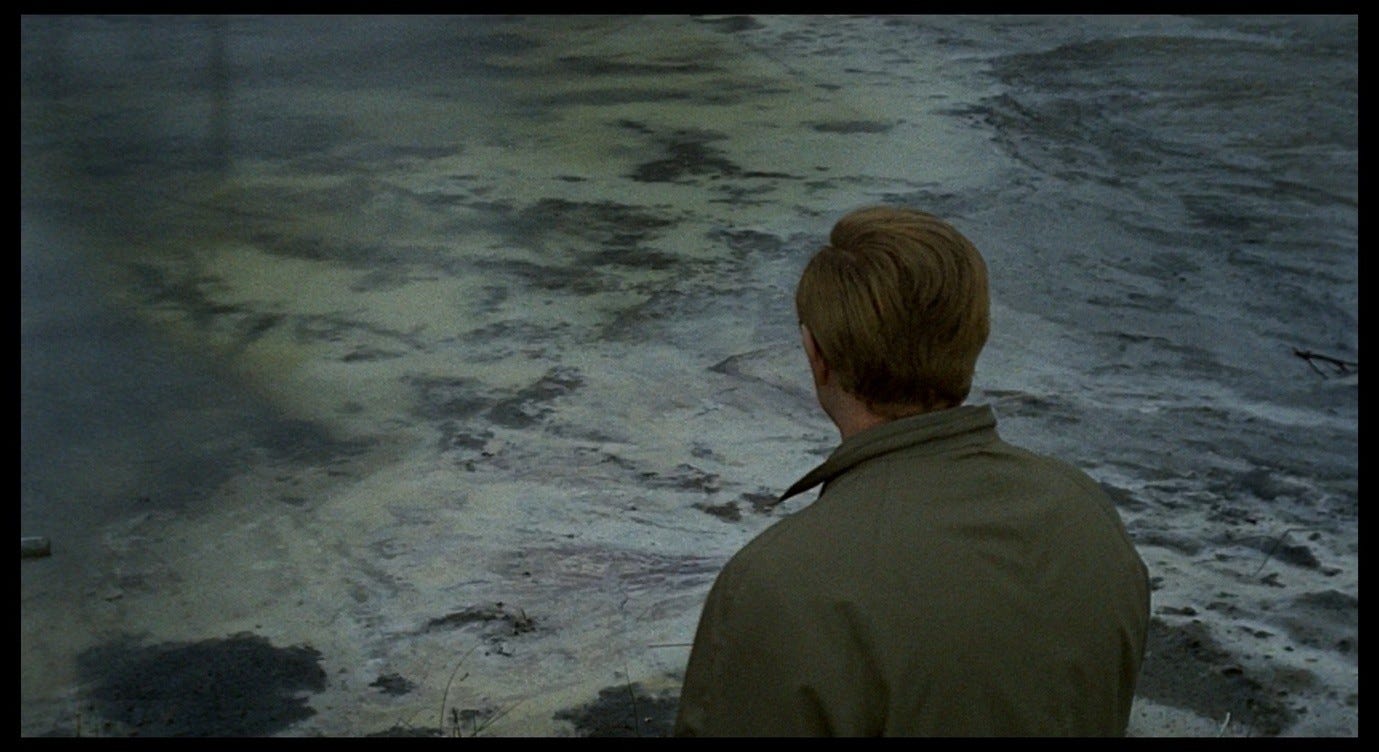

Once again, we have a sequence that begins with a disorienting transition, cutting straight from the Medicina observatory to Corrado standing by a lake, looking around him and saying ‘What a shame.’

The characters have come out here expecting to enjoy themselves in a pastoral idyll, but pollution has (very visibly) rendered this impossible. The previous sequence showed an extended work trip, and it feels jarring to learn that the characters are now in leisure-mode, all the more so because leisure-mode is undercut as soon as it is introduced. As William Arrowsmith says, referring to similar jarring transitions in L’eclisse:

The purpose of this kind of cutting is not merely contrast but rather incongruity of mood and tempo, the effort to describe time itself as dissonant, discontinuous, disjointed. The reeling and tilting of the changing world, the shifting reality that makes life so provisional and difficult, are thus everywhere suggested by a violent alternation of landscapes […] brusquely enjambed.10

The distinctive thing about the cut from Medicina to the swamp in Red Desert is the congruity of mood and tempo. We feel like we are in the same place, on the same work trip, but we are not. In some ways, Antonioni may be even more interested in this aspect of life’s ‘provisionality’: the fact that reality does not shift when it ought to, that spaces merge together not brusquely but with a sinister ease.

Ugo, also looking at the lake, responds: ‘The effluent from all these factories has to end up somewhere.’

The natural habitat is yet another kind of empty space, ready and waiting to be filled up with pollutants. Giuliana contemplates the water and then turns away from it to re-join the others – as we pan left we realise this is the same camera set-up as the previous shot – telling an anecdote about a polluted eel and thereby associating this sequence with the eel encounter in Ferrara.

The workings of industry, as delineated by earlier scenes, have impacted the sphere of leisure. Even when these people step away from their jobs, they still find themselves living amongst pollution, consuming polluted food; in some shots, the smoke from the factories is clearly visible in the distant background.

The screenplay describes the polluted lakes in some detail, and encapsulates the desired effect in concise stand-alone phrases like ‘An unclean water [Un’acqua immonda]’ or ‘A desolate landscape [Un paesaggio desolato].’11 The swamp-like bodies of water become yellower and weirder as the scene progresses.

Some of the bare trees have turned purple, more noticeably so if you are watching the Madman edition (from which the next two screen-captures are taken).

The oiliest of the swamps fills the screen. Corrado steps into frame and peers at this spectacle as though he were looking at an artwork in a museum; he seems intrigued by its swirling black-and-yellow textures. Indeed, the image recalls the abstract art in Ugo’s factory and apartment or the Nuclear Art of Enrico Baj (see Part 11).

Pollution entails a violation of boundaries, the intrusion of one substance or state into another: clean water made unclean, a fertile landscape made desolate, a fishing spot transformed into a receptacle for effluent. Antonioni also suggests that the beauty of this natural landscape has not simply been destroyed by industry, but transmuted into another kind of beauty. The advances and effects of industrialisation have taught us to admire and appreciate new aspects of the world around us, just as the art movements of the early 20th century have taught us to look differently, and at different things, when we engage with art. The corruption that makes this place unsuitable for a pleasant outing also makes it an object of fascination for Corrado, and apparently for Giuliana as well: she almost cannot tear herself away from the acqua immonda.

She is equally fixated by the sight of a large ship sailing through the pine forest on the horizon. The swamp is so pervasive, and the landscape so desolate, that the distinction between land and water has broken down. We see the ship; we see Giuliana watching the ship; then, when we cut back to the ship, a car drives past in the opposite direction.

Something about the juxtaposition of these two moving objects seems to undo the illusion of the ship sailing through the forest. Seeing the car (and briefly seeing water churned up in the ship’s wake) reassures us that the land is the land and that the ship is travelling on a different surface, farther away. Giuliana’s expression becomes more relaxed, but she still lingers in this spot, hypnotised by her surroundings. She closes her eyes and raises her face to the sky, savouring something in the atmosphere. Then she turns away from us to look at something else – another yellow pond, as it turns out.

Karen Pinkus accounts for the mood of unreality in the ship-through-the-forest sequence by relating it to a recurring pattern in Red Desert’s ship imagery:

At several points in the film ships pass through the canals, their prows appearing from off-screen and moving from left to right. These images are disconcerting because of the proximity of the ships to structures on land, but also because we do not see them coming – they emerge from the fog […] so that we can no longer be certain we are watching a realist film. […] [Antonioni] undoes any sort of certainty about borders between the visible and invisible or outside and inside that would make us comfortable determining the film’s ambiente.12

These vessels are too close – not just to ‘structures on land,’ but to land as such – and yet we cannot see where they come from; one moment they are nowhere to be seen, then suddenly they are upon us. Pinkus frames this in terms of the viewer’s anxiety rather than Giuliana’s. Is this a realist or surrealist film? Is this what Giuliana ‘really’ sees or is it meant to evoke her inner state? The word ambiente will come into play later in this sequence when Corrado uses it, and there is more to say about this connection between the characters’ sense of their own context and our sense of the world this film conjures up.

For Christine Henderson, the gaze Giuliana directs at the ship and the swamps is indicative of her troubled mental state:

At times her eyes drift, her gaze gliding over the surface of the world, as though it were a non-demarcated, smooth, homogeneous surface, as though there were nothing to see; while at other moments, she is captivated by a particular image or sound that acquires an unwarranted gravity, a hyper-realization, that detaches it from any possible context and enables it to function as a floating signifier indicative of anxiety, of trauma.13

As I argued in Part 17, Henderson’s approach to Giuliana’s illness – while thought-provoking – can sometimes be reductive, as here in her use of the word ‘unwarranted’. Who decides whether these images and sounds are being invested with warranted or unwarranted gravity? Ugo has stated, exhibiting the mentality of a machine, that ‘effluent has to end up somewhere,’ viewing cause and effect with a cold, lucid eye. The ruined environment can be written off as casually as the waste products that ruined it. This is what factories do and Ugo accepts it with a shrug – for him, there is nothing to see here. Unlike her husband, Giuliana takes the time to look at this transformed landscape and process her own reaction to it. This is an important development, because it shows Giuliana doing more than just recoiling in terror from the world she finds herself in. Those panicked, allergic reactions, as well as the ‘unwarranted’ attention she pays to certain phenomena, may indicate sensitivity and responsiveness. Others may take things in their stride because they are not paying attention. In many of Antonioni’s ‘daytrips gone wrong,’ there is a distinction between the characters who notice something is wrong and those who insist that everything is fine. The behaviour of the latter is symptomatic of the problems being pointed out by the former.

It may also be worth questioning Henderson’s suggestion that certain images – certain objects of Giuliana’s gaze – are detached from ‘any possible context.’ This is indeed the effect sometimes achieved by Antonioni’s blurry or too-close images, but de-contextualisation is often followed by re-contextualisation, as in the image of the ship-in-the-forest which is clarified by the appearance of road-vehicles and churning water. The idea of images removed from any kind of context, serving as floating signifiers of Giuliana’s anxiety and trauma, overlaps with Pauline Kael’s reading of La notte and Red Desert as films made up of ‘emptied out’ images, appealing only to viewers who can latch onto those hazy, floating pictures and make them signify their own narcissistic hang-ups. The daytrip, like the desert, is a new ambiente, not a total absence of context. It is a place where contexts – familiar and unfamiliar, for better or worse – can be tried out and played with. Revelations about Giuliana’s illness will emerge from this ‘play’, but we should hold onto the idea that she is seeing and hearing things that are really there in her ambiente, and that the gravity she ascribes to them is warranted.

Next: Part 19, Industry, exploitation, and ‘Sick Eros’.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 37

Nardelli, Matilde, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), p. 171

Kael, Pauline, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Boston: Little, Brown, 1968), pp. 30-31

Kael, Pauline, et al., ‘Films of the Year’, Film Quarterly 15.2 (1961-1962), pp. 35-37; p. 35. Also available via Scraps From the Loft.

Kael, Pauline, I Lost It at the Movies (London: Cape, 1966), pp. 163-167. First published as ‘The Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties: La Notte, La Dolce Vita, Marienbad’, in The Massachusetts Review 4.2 (1963), pp. 378-391. Also available via Scraps From the Loft.

Kael, Pauline, I Lost It at the Movies (London: Cape, 1966), p. 175. First published in The Massachusetts Review 4.2 (1963), pp. 378-391 (the footnote does not appear in this version). Also available via Scraps From the Loft.

Kael, Pauline, 5001 Nights at the Movies (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1985), p. 487

Kael, Pauline, 5001 Nights at the Movies (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1985), p. 487

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 60

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 73

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; pp. 455, 459

Pinkus, Karen, ‘Antonioni’s Cinematic Poetics of Climate Change’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 254-275; pp. 269-270

Henderson, Christine, ‘The Trials of Individuation in Late Modernity: Exploring Subject Formation in Antonioni’s Red Desert’, Film-Philosophy 15 (2011), pp. 161-178; p. 170