Everything That Happens in Red Desert (44)

Corrado's exit

This post contains discussion of rape and incest (after the row of asterisks), as well as spoilers for Homo Faber.

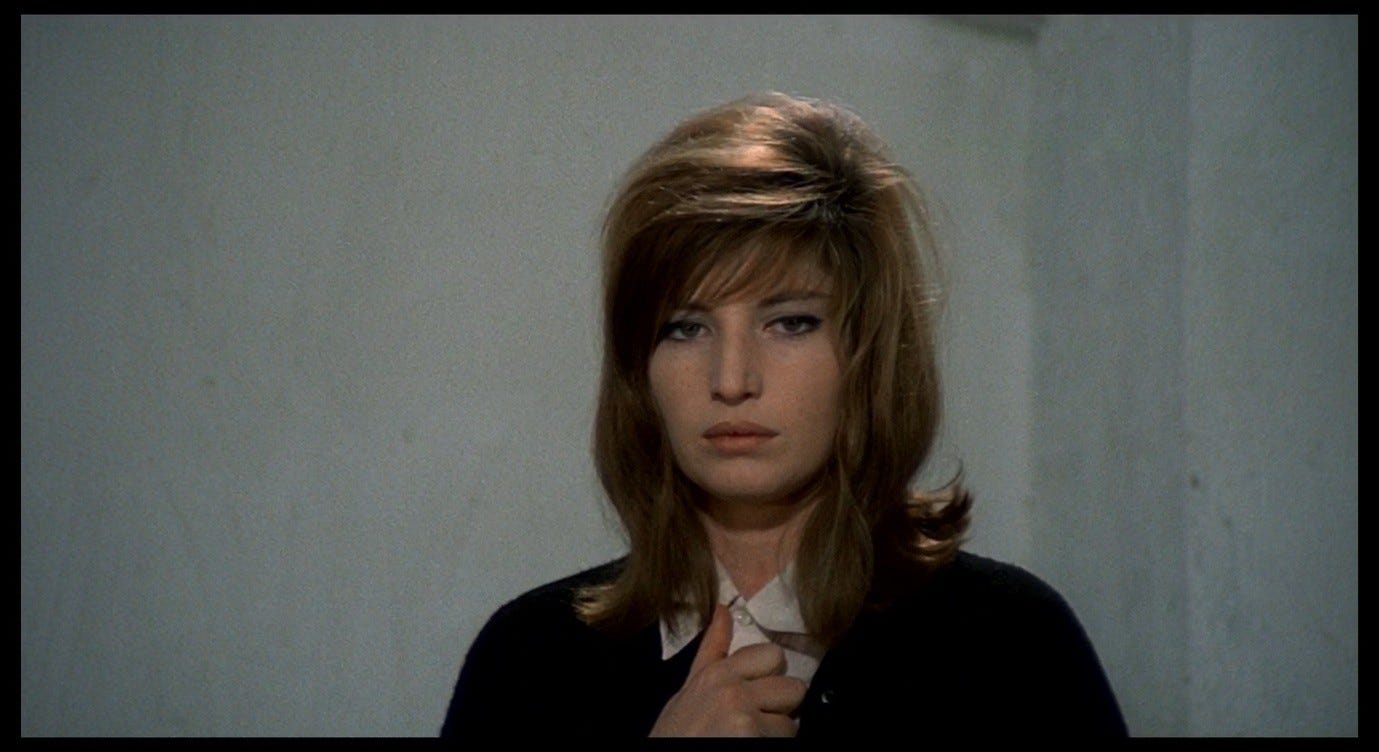

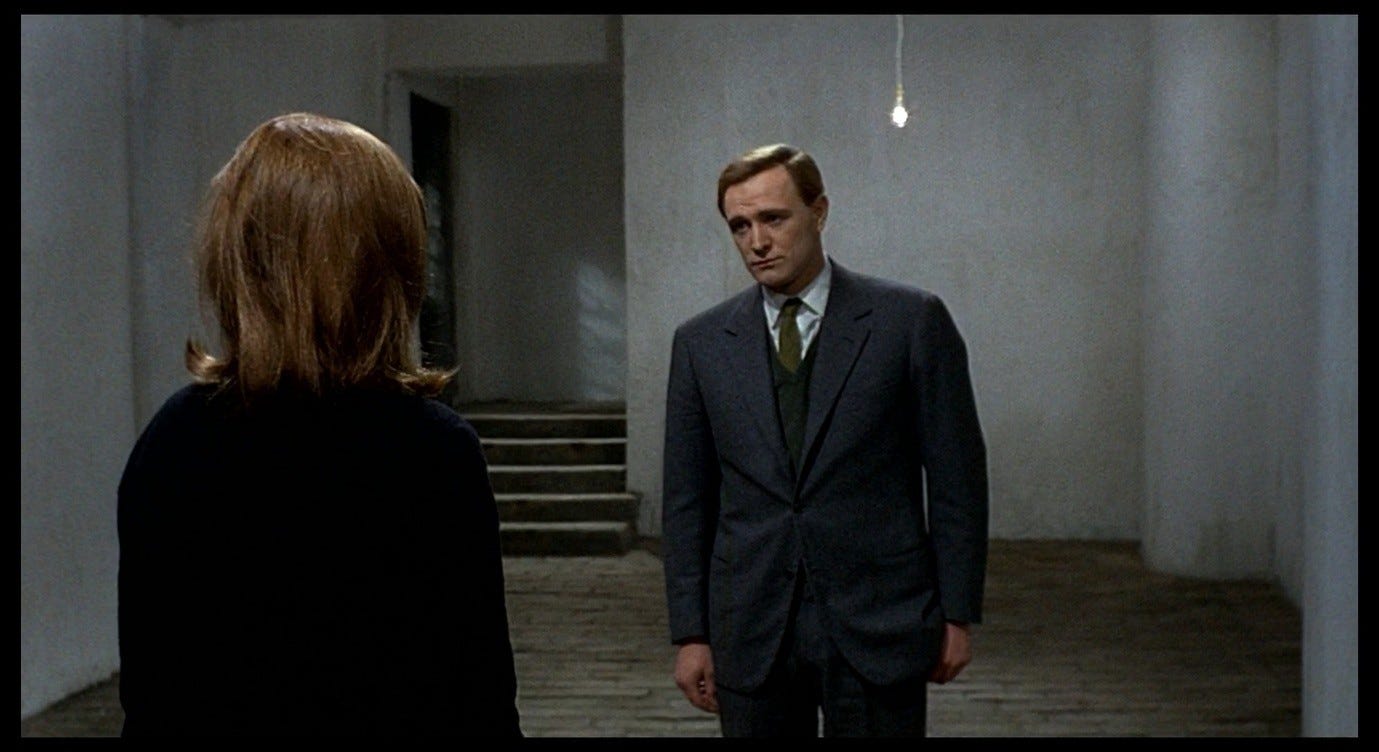

‘Even you haven’t helped me,’ says Giuliana to Corrado, having stepped out of her alcove and walked towards him (and the camera).

The screenplay makes a distinction between Giuliana’s intent and Corrado’s interpretation: ‘She says this sweetly [con dolcezza], but for Corrado it is like an accusation.’1 The dolcezza is not particularly evident in the finished film. Monica Vitti delivers her line sadly, with a subtle break in her voice, and a few seconds later when she watches Corrado walk away, her expression conveys resignation and disappointment, not affection.

The phrase neanche tu (‘not even you’) might imply a number of things: that Corrado has come closest to helping her (but not quite succeeded), that he has tried harder than anyone else (but it was a futile effort), or that he had the capacity to help (but chose to take advantage of her instead). The first two meanings might carry a tone of dolcezza, a degree of tenderness and even gratitude for this would-be friend who has done the best he could. But the third meaning, the accusation, is the one that makes sense in the context of what we have seen in the last few minutes. If anything has set Corrado apart from other people, it is his talent for comprehension. ‘If Ugo had looked at me as you do,’ Giuliana said on the SAROM rig, ‘he would have understood many things.’ Now, Corrado can be trusted to understand Giuliana’s statements about the ‘terrible thing in reality,’ about her ‘success in becoming an unfaithful wife,’ and about his own failure to help her. He can also be expected to flee from this understanding into a state of denial and absence.

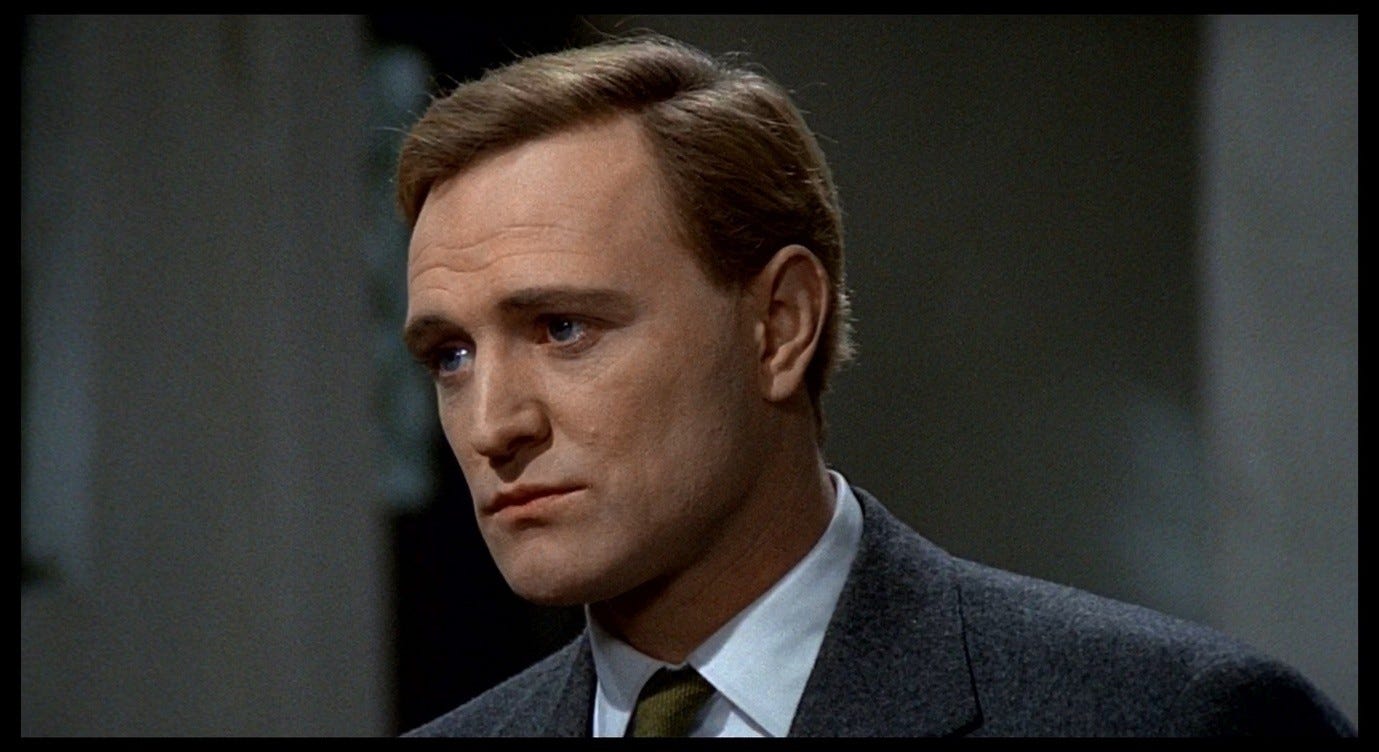

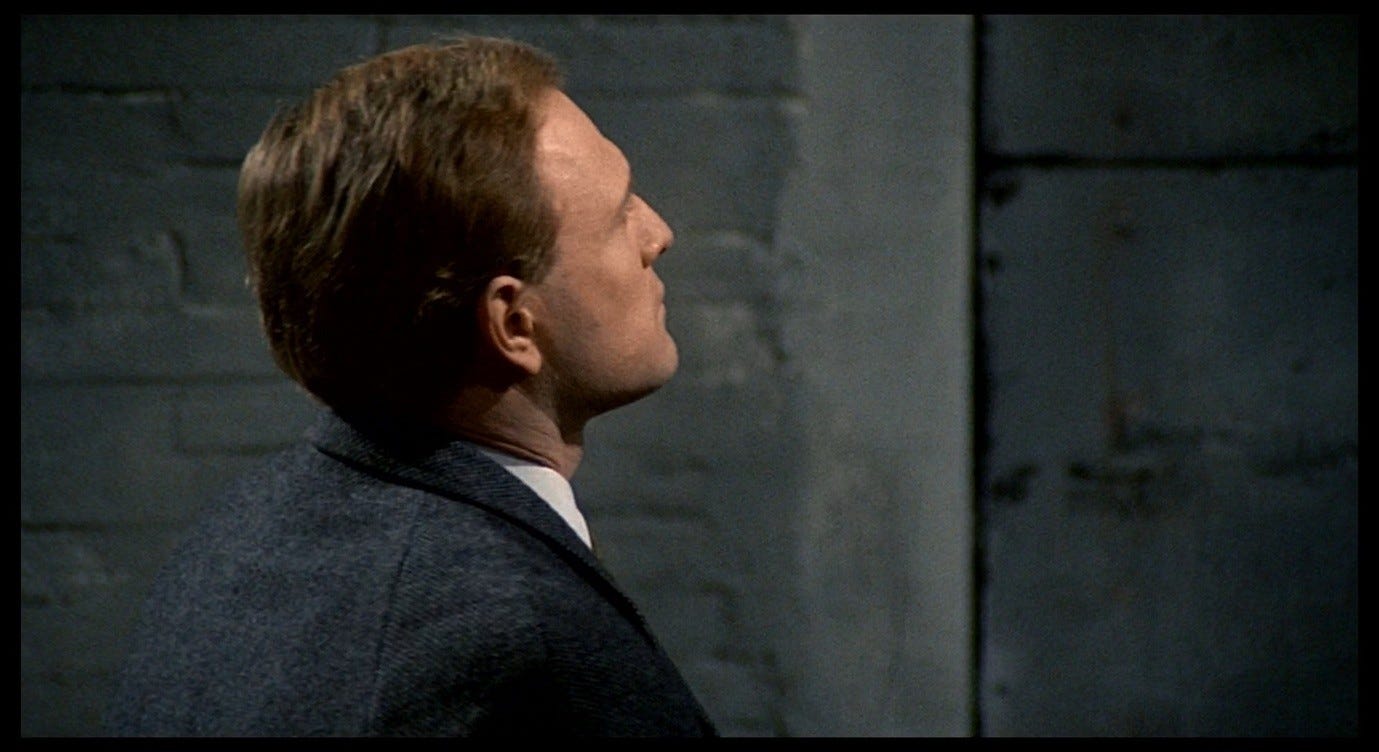

Corrado’s reaction shot shows his face, completely in focus, occupying almost the whole frame – we see him more clearly and completely than in the rest of this scene – but his expression is not legible as that of a man who feels ‘accused.’

There is a hint of sadness in his eyes, but since Richard Harris’s resting expression is one of seething gloom, we cannot infer anything from this shot about his specific reaction to Giuliana’s comments. His expression does not change as he picks up his coat, puts it on, and walks out into the dark street. The telephoto lens captures the movements of his head in a huge, uncomfortable, out-of-focus close-up while he ascends the steps to reach the door.

As when a news camera follows a disgraced politician to their car, it feels as though we are intrusively trying to capture Corrado’s reactions, to read his emotions, and he is refusing to show any.

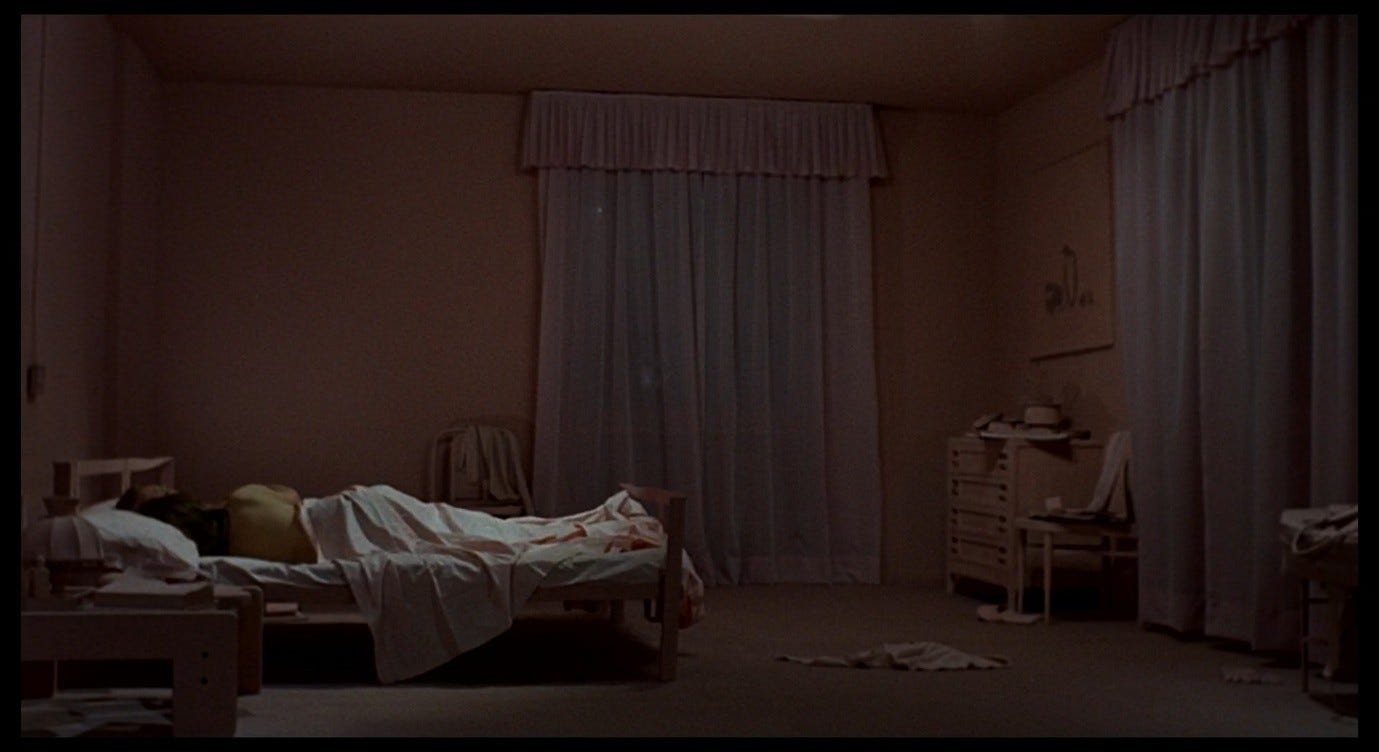

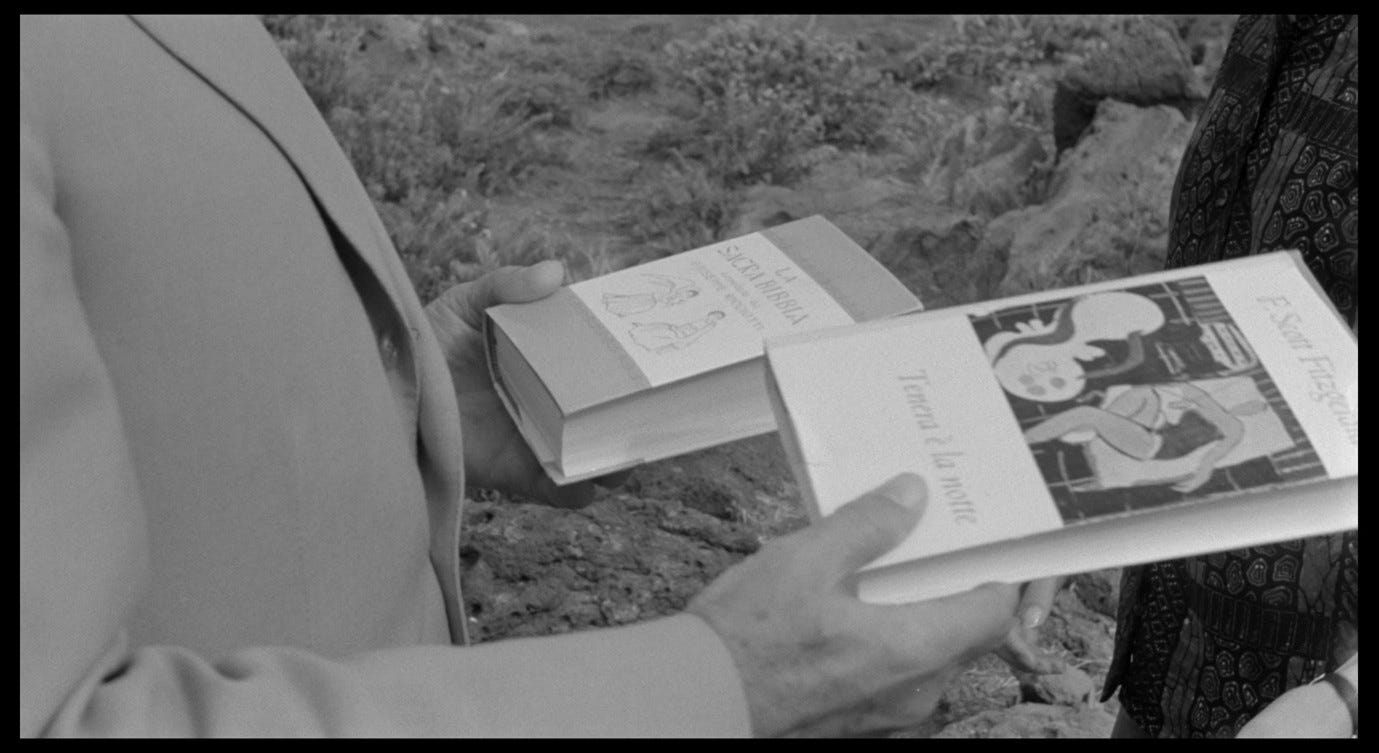

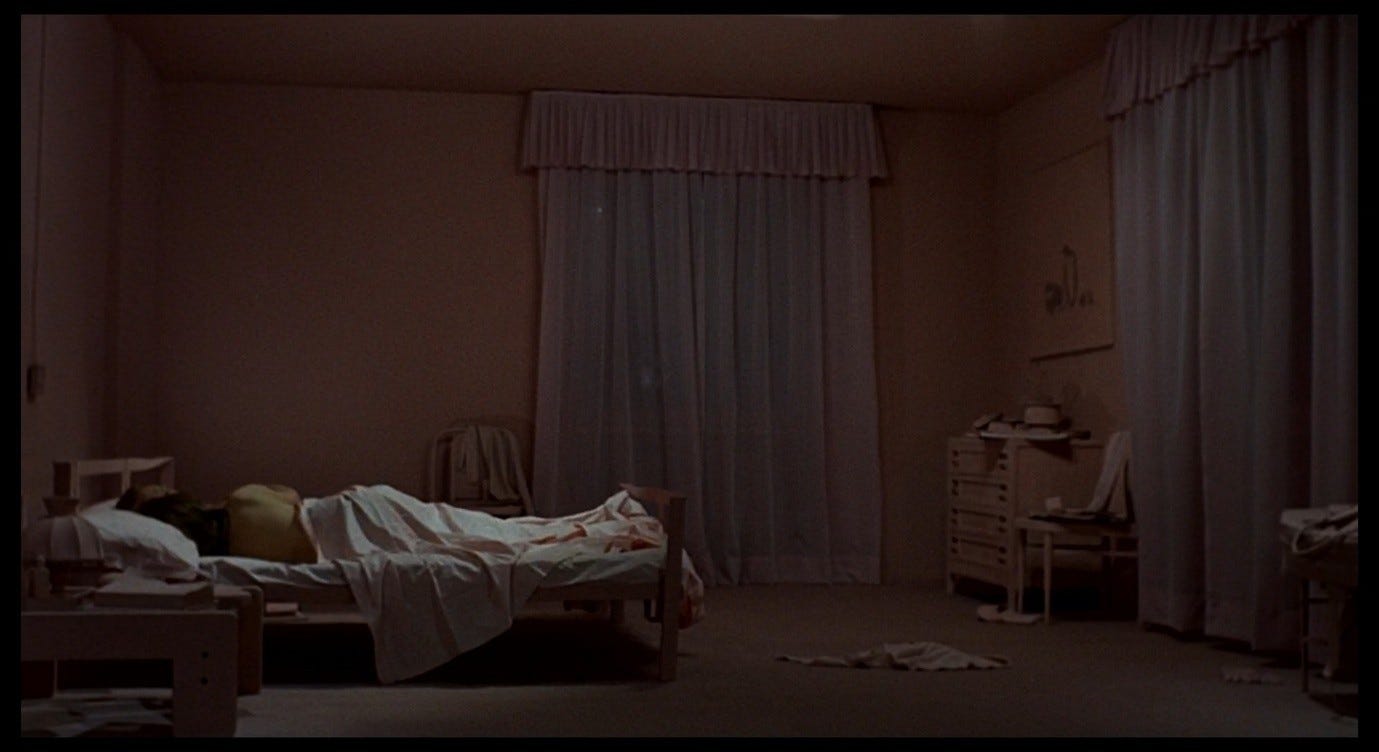

His inscrutability is similar to that of Walter Faber, the narrator-protagonist of Max Frisch’s novel Homo Faber, which lay on Corrado’s bedside table in his hotel room.

Faber’s worldview, which he reiterates frequently throughout the novel, can perhaps be summed up as ‘there is nothing terrible in reality.’ As he looks back at the tragic events of his life, he insists that they are merely a series of extraordinary accidents with no larger significance:

I don’t deny that it was more than a coincidence which made things turn out as they did, it was a whole train of coincidences. But what has providence to do with it? I don’t need any mystical explanation for the occurrence of the improbable; mathematics explains it adequately, as far as I’m concerned.2

Near the start of the novel, when Faber finds himself marooned in what he calls ‘the red desert’ (il deserto rosso in the Italian translation Corrado is reading)3 following an emergency plane-landing, he meditates on the contrast between his own emotions and those of a fellow passenger:

I admitted that landscapes didn’t mean much to me, and certainly not a desert.

‘You don’t mean that!’ he said. He thought it experience. […]

I’ve often wondered what people mean when they talk about an experience. I’m a technologist and accustomed to seeing things as they are. I see everything they are talking about very clearly; after all, I’m not blind. […] I see the jagged rocks, standing out black against the moonlight; perhaps they do look like the jagged backs of prehistoric monsters, but I know they are rocks, stone, probably volcanic, one would have to examine them to be sure of this. Why should I feel afraid? […] I see what I see – the usual shapes due to erosion and also my long shadow on the sand, but no ghosts. Why get womanish? I don’t see any Flood either, but sand lit up by the moon and made undulating, like water, by the wind, which doesn’t surprise me; I don’t find it fantastic, but perfectly explicable.4

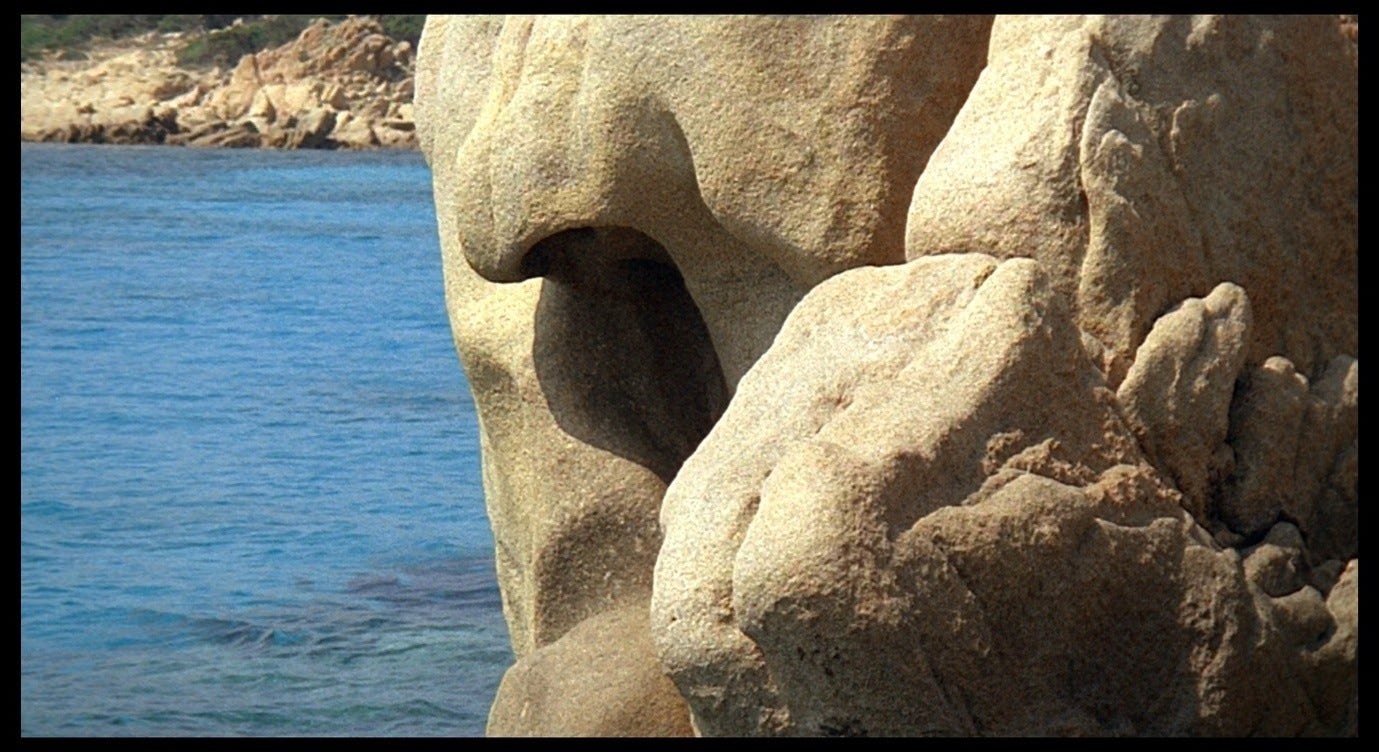

His initial rejection of the idea of providence turns out to be something deeper, a rejection of any kind of meaning (beyond the mathematical) in events or objects. The examples he gives in the passage just quoted are especially resonant in the context of Red Desert. Where the cove-dwelling girl in Giuliana’s story sees human figures and hears ghostly voices in the flesh-like rocks surrounding her, Faber would insist they are simply rocks. Where Giuliana often finds reality disintegrating and liquefying around her, Faber would insist that the desert sand is simply ‘like water’ due to the effect of the wind. To go beyond this down-to-earth comparison, to feel any sense of awe or existential terror in the face of these uncanny resemblances, is ‘womanish.’

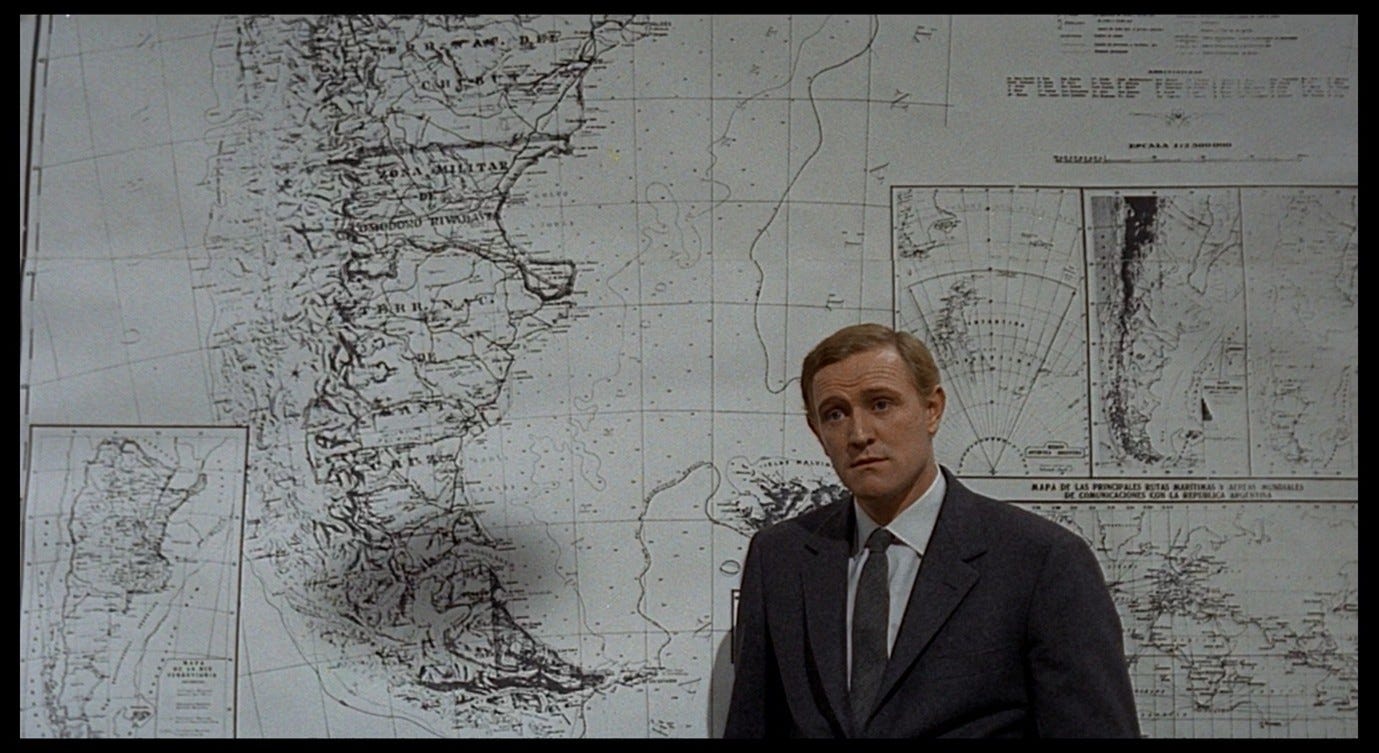

Like Corrado, Faber works in industry, and is busy setting up a new project in South America. He is frequently preoccupied with thoughts of turbines in Venezuela, but finds himself distracted by his fraught emotional ties to a former girlfriend, and to a young woman who turns out to be his daughter by that girlfriend. Although the specifics of the plot differ from those of Red Desert, the overall pattern – of a pragmatic engineer involved in a disturbing relationship with a woman – is strikingly similar. Faber’s no-nonsense attitude towards ‘womanish’ fears anticipates Corrado’s tendency to dismiss and downplay Giuliana’s illness, but in both cases this pragmatism is framed as a symptom of emotional repression. Corrado, spacing out during the briefing for his Patagonian project, is clearly shaken by his encounter with Giuliana, but seems unable to express this feeling to her or to himself.

Faber is similarly confused by his own absorption with a long-lost relationship:

I should have landed in Caracas a week ago and today (at the latest) I ought to have been back in New York. Instead of that I was stuck here – for the sake of saying hello to a friend of my youth, who had married the girlfriend of my youth. What for?5

He often asks questions like this, or professes not to understand his own feelings and motivations. The philosophy that makes him see only sand and rocks in the desert also makes him blind to emotional or psychological states, to anything internal. His ignorance of his own reasons for looking into the fate of Hanna, the girlfriend of his youth, dovetails with his ignorance about why that relationship failed:

I made up my mind to marry Hanna, if ever her residence permit were withdrawn. […] I had made up my mind, as I have said, but I never got round to it. I don’t really know why. Hanna was always very sensitive and moody, an unpredictable temperament – manic-depressive, as Joachim said. […] I called her a sentimentalist and arty crafty. She called me Homo Faber. […] [She had a] tendency to mysticism, or to put it less kindly, hysteria. Now, I am a man who has both feet on the ground.6

His stated motives for marrying Hanna are purely pragmatic and rooted in concrete needs (the withdrawal of her residence permit) and we might infer that their separation was caused by his inability to engage with her ‘manic-depression,’ or ‘sentimentality,’ or ‘hysteria,’ or with whatever aspects of her character Walter is trying to smooth over with these terms.

Walter assumes that Hanna had an abortion after their separation, but years later he finds himself in a tentative affair with the daughter he never knew he had:

I wasn’t in love with the girl with the reddish pony-tail, she attracted my attention, that was all, I couldn’t have suspected she was my own daughter, I didn’t even know I was a father.7

The daughter, Sabeth, dies following an accidental fall. In a series of disjointed and repetitive notes, Walter recounts Hanna’s philosophical take on this series of events. The notes serve as a commentary on Walter’s rejection of ‘experience’ in the red desert, as well as recalling Hermann Broch’s commentary on the ‘singleness of purpose’ that (according to Broch) makes the modern world so alienated:

Discussion with Hanna – about technology (according to Hanna) as the knack of so arranging the world that we don’t have to experience it. The technologist’s mania for putting the Creation to a use, because he can’t tolerate it as a partner, can’t do anything with it. […] (I don’t know what Hanna means by this.) The technologist’s worldliness. (I don’t know what Hanna means by this.) Hanna utters no reproaches, Hanna doesn’t find the way I behaved towards Sabeth incomprehensible; in Hanna’s opinion I experienced a kind of relationship I was unfamiliar with and therefore misinterpreted, persuading myself I was in love. It was no chance mistake, but a mistake that is part of me (?), like my profession, like the rest of my life.8

Again, Walter repeatedly comments on his own ignorance, his inability to understand the ‘meaning’ of Hanna’s statements, or of the events of his life, or of the objects around him. Hanna’s perspective is defined by comprehension and understanding but we hear it only through the filter of Walter’s partial comprehension. His confusion and his questions (reduced, finally, to a bracketed question mark) do not point us in the direction of the truth; the reader cannot smugly infer that truth and thus distinguish themselves from this unreliable narrator. Rather, Walter’s comments leave us confused and questioning, like him. No wonder he cannot tolerate ‘the Creation’ as a partner, no wonder he tries to avoid experiencing it, when such experiences are as painful and confusing as the ones he describes. From his original stance, which I characterised as ‘there is nothing terrible in reality,’ Walter seems to have transitioned into ‘there is something terrible in reality, and I don’t know what it is.’ Now, he is not so sure of the boundaries between states, or of the stability of his environment:

Since my forced landing in Tamaulipas I have always sat so that I can see the undercarriage when they lower it, anxious to observe whether the runway at the last minute, when the wheels touch it, does not after all change into a desert.9

His visit to the red desert was an ‘experience’ after all. That place was not simply a desert, it meant something, and that meaning resonated through his subsequent coincidence-filled encounters with Sabeth and Hanna. The red desert, he now realises, can be anywhere and everywhere – you never know when you will find yourself stranded in it.

Walter’s comment on the red desert, near the start of the novel, occurs in the context of a series of colourful comparisons he makes while staring out of the window of the plane, just before its forced landing:

[T]he swamps were green in some places and in others red, the red of a lipstick, something I couldn’t understand, they were really not swamps but lagoons, and where they reflected the sun they glittered like tinsel or tinfoil, anyhow with a metallic glint, then again they were sky-blue and watery (like Ivy’s eyes). […] In the distance the blue mountains. Sierra Madre Oriental. Below us the red desert.10

This passage lays the groundwork for Walter’s insistence that similes are just similes, that objects are coloured in certain ways, or resemble other objects, for empirically verifiable reasons, and that it is ‘womanish’ to read anything into these resemblances. But these protests themselves turn out to have an underlying emotional significance, as we learn during Walter’s account of his affair with his unrecognised daughter. Sabeth initiates a ‘game of comparisons’ in which the players compete to compare things to other things. For instance:

[A] few small morning clouds hung overhead – like tassels sprinkled with pink powder, thought Sabeth; I couldn’t think of anything and lost another point.11

After his daughter’s death, Walter is still haunted by her superior talent at this game:

The crevasses – as green as bottle-glass. Sabeth would have said: as emerald! Our twenty-one points game again. The rocks in the evening light – like gold. I think: like amber, because lustreless and almost transparent, or like bone, because pale and brittle.12

The tassels sprinkled with pink powder make me think of the powdery pinkness covering Corrado’s hotel room.

The rocks that turn into lustreless, almost transparent amber, then into pale and brittle bones, are like the surfaces in Giuliana’s tale of the pink beach, transitioning from transparent water, to sand, to rocks that look like bodies, to one last rock that resembles a skull, before the image dissolves altogether (catching, as it does so, a golden/amber glow in the reflection of a rock in the water).

Sabeth’s habit of blurring the boundaries between objects and the things they resemble seems to have been internalised by Walter since her death and before he begins his narration, hence his comparisons when describing the landscape outside the plane (‘red of a lipstick…like tinsel or tinfoil…like Ivy’s eyes’). Although, at the start of the novel, he tries to downplay the significance of these comparisons, by the end, having told the story through, he has embraced the multiplicity of his surroundings – now he would perform better in Sabeth’s game.

In a similar way, Corrado begins to see the world as Giuliana does, especially in the briefing sequence when his eyes wander across the blurred faces and weirdly fascinating shapes in the warehouse. But unlike Walter, Corrado ultimately rejects this way of seeing and retreats into the mindset of the technologist who arranges the world so as not to experience it. ‘You shouldn’t think about such things’ is his final line in the film, and his final verdict on Giuliana’s troubles. The phrase she then uses to describe the ‘something terrible’ in reality – qualcosa di terribile – invokes something like Sabeth’s comparison game, which finds ‘something of’ one thing in another. As Paul Youngman says, Faber begins the novel believing that ‘his sense perception […] reveals the essence of objects to him,’ that these objects are easily categorised, and that ‘there can be no fruitful interplay between them.’13 This is, perhaps, the flipside to Corrado’s ‘understanding’ gaze that initially makes him a good listener to Giuliana: he also has Walter Faber’s need to make every object explicable, every problem solvable, and with this Faber’s tendency to respond to inexplicable or inescapably problematic relationships by looking away from them. ‘His constant criss-crossing of continents is merely the outward indication of a personal rootlessness,’14 says Michael Butler, with reference to Faber, but the statement is obviously applicable to Corrado as well. In Frisch’s novel, this state of denial is replaced by one of tragic awareness, but Corrado rejects this awareness and continues on his travels.

We watch Corrado through the open doorway of Giuliana’s shop, initially in a medium close-up – a continuation of that intrusive telephoto-lens shot that followed his progress to the door.

Corrado goes out into the darkness of the Via Alighieri. He pauses for a moment and looks up, as Giuliana did at the walls of her shop earlier in this scene. Like her, he seems to take a moment to register the failure of this relationship. He looks down despondently, and we cut on this action to a wide shot of the cobbled street.

Corrado slowly walks out of shot. For the last few seconds, his footsteps have been the only sound we could hear. Now, as he walks away, he places his feet more and more gently on the cobbles, causing his steps to become quieter – they fade into silence at the same moment when he leaves the frame. When his shadow on the wall disappears as well, we cut to the next scene.

Corrado’s final moments in Red Desert recall Walter Faber’s meditation (halfway through Homo Faber) on the joys of solitude:

One of the happiest moments I know is the moment when I have left a party, when I get into my car, shut the door and insert the ignition key. […] [P]eople are a strain as far as I’m concerned, even men. As to my fluctuating spirits, I pay no attention to them. Sometimes you feel low, but you pick up again. Fatigue phenomena! As in steel. Feelings, I have observed, are fatigue phenomena, that’s all, at any rate in my case. You get run down. Then writing letters doesn’t help you to feel less lonely either. It doesn’t make any difference; afterwards you still hear your own footsteps in the empty flat. […] Then I just stand there with gin, which I don’t like, in my glass, drinking; I stand still so as not to hear steps in my flat, steps that are after all only my own. The whole thing isn’t tragic, merely wearisome. You can’t wish yourself good night… Is that a reason for marrying?15

Corrado, like Walter, seems to want to avoid hearing his own footsteps, to walk silently as though he did not really exist, or as though there were no necessity to interact with the world around him. Walter is dismissive of reflection (‘writing letters’), comparisons (‘the footsteps are only my own’), or any deeper emotional significance in experiences (‘fatigue phenomena, that’s all; not tragic, merely wearisome’). His emotional repression even extends to drinking alcohol he does not like, and his philosophy is ultimately a justification for rejecting human relationships – why marry just to have someone wish you goodnight?

Hanna’s nickname for Walter, Homo Faber, is a play on both ‘man the maker’ and the notion that Walter is a species unto himself, not homo sapiens but a mutation that replaces wisdom with fabrication, that builds relentlessly (either ‘downwards’ or ‘upwards,’ as Corrado defined the phases of his career) to avoid looking inwards. In another passage, Walter reacts angrily to someone who claims that industrialisation is ‘the last gospel of a dying race and living standards a substitute for a purpose in living.’16 Man-the-maker builds more and more efficient, comfortable homes, then stands silently in them drinking liquor he dislikes in order to drown out the sound of his own footsteps. Corrado’s comment about ‘travelling around and ending up back where you started’ (made during the shot in which Homo Faber appears) alludes perhaps to the circular life of Walter Faber, who leaves Hanna only to enter a relationship (years later) with their daughter, and who ends up back with Hanna herself at the end. It is a tragic circularity that results from (and exposes) that inability to reflect on or to articulate emotions, which both Walter and Corrado see as a strength.

The framing of Corrado’s final shot emphasises the limited, benighted exterior space in which he operates. As in the earlier Via Alighieri sequence, the street is conspicuously grey, a place of foggy, ashen obscurity. We remain inside, in the company of that terrible-thing-in-reality that Giuliana is still coming to terms with. The open doorway may remind us of how Corrado, on first arriving here, glanced inside and then retreated; and then of how Giuliana opened the door and invited him in.

In their final conversation, Giuliana is more open and vulnerable than ever, describing her (seemingly incurable) illness as clearly and directly as she can. Corrado sees and hears Giuliana’s agonised confession, but says nothing and walks away through (and then from) the open door.

* * * * *

Among other documents relating to Red Desert, the Antonioni Archive contains a note by the director which is summarised (by the archive curators) as follows:

Reflection on one’s indifference [propria indifferenza] towards the theme of incest in literature (with references to Homo faber by Max Frisch and The Man Without Qualities by Musil).17

There is something paradoxical about reflecting on one’s own indifference to something: if the topic is noteworthy enough to reflect upon, it is clearly not a matter of complete indifference. In his story, ‘The event horizon’, Antonioni sets up a very Homo Faber-esque premise about six people involved in a plane crash, one of whom asks (just before the fatal event) about the nature of death. Her lover, a writer, refuses to engage:

He was totally uninterested in the problem [Il suo disinteresse per l’argomento era totale]. His advice was that it’s better not think about it [meglio non pensarci]. She looked at him with contempt. […] It’s too easy to talk about death only to say that it’s better not to think about it, she said.18

The woman’s response, and the phrase meglio non pensarci, recall Giuliana’s sarcastic response to Corrado, ‘Basta non pensarci, bella conclusione.’ Corrado has just told her not to think about what happened between them in the hotel room, but she insists on pointing towards that qualcosa di terribile nella realtà that no one will discuss with her. She is, more broadly, drawing attention to the malattia dei sentimenti around which all Antonioni’s work revolves, and which manifests in various forms: as a fear of mortality (as in ‘The Event Horizon’), as a fear of change or transience in general, as a fear of societal and technological progress, and most intensely of all, as a nebulous set of fears around sexuality. It is these fears, especially the ones relating to sexual violence, that are most insistently subsumed under the mantra, basta non pensarci. When Claudia objects to being sexually assaulted in L’avventura, Sandro tells her she should be happy about her avventura nuova, and his dismissive tone horrifies her. When Giovanni assaults Lidia at the end of La notte, he keeps telling her to sta’ zitta (be quiet). The rape scene in Red Desert is positioned as the culmination of Giuliana’s fears (of ‘factories, streets, colours, people, everything’), but it is portrayed elliptically and then spray-painted pink; not white-washed but pink-washed, in a way that erases distinctions and leaves us with ‘nothing to see’ besides that one tonally overwhelming colour.

Incest is another form of abusive sexual violence that recurs in Antonioni’s work, but it is figured even more intensely as a taboo topic over which a veil must be drawn. It is pointedly regarded with indifferenza and disinteresse, but as in the above-quoted passages, this lack of interest is very deliberate and therefore self-deconstructing. In another story, ‘The girl, the crime’, Antonioni describes an encounter with a woman who murdered her father by stabbing him twelve times. He asks her why she did it, and she ‘shrugs her shoulders and her gesture […] is clearer than any answer.’19 He ends the story by reflecting on his own emotional state in relation to his environment, and on a questionable decision he might have made if he had turned this anecdote into a film:

The disturbing point was […] that I felt twelve stabs were much more familiar [molto piú familiari] than two or three.

The first rays of the sun came from the sea to touch the chairs about six o’ clock. And suddenly everything was clear to me, as were the sea, the houses around the bay, and the rest, in the sunlight. In that chilling number there was everything that there had to be [tutto ciò che doveva esserci] in that story, there was truth [c’era la verità]. Not only the intrinsic truth of the crime, but also that of an outsider like myself, of anyone.

[…] I couldn’t have managed now to resume my own story except by telling myself lies. The girl’s look of awareness [sguardo consapevole] […] had remained inside me and fixed me with tragic irony. […] [T]he same irony of the sunlight that was now touching everything, falling over everything like Joyce’s snow, over all the living and the dead [su tutti i vivi e su tutti i morti].

[…] I was tired and irritated. As though I had just finished shooting the scene of the knifing and, instead of twelve blows, I’d decided that three were enough. Out of prudence [Per discrezione].20

As I said in Part 16, I think William Arrowsmith’s translation of discrezione as ‘prudence’ subtly distorts the original text. If a film-maker reduces the number of stabs out of prudence, what are they being prudent about? This is a pragmatic decision motivated by concerns about how the film might come across and how the audience might react; too many stabs would be excessive, unbelievable, gratuitous. But if the director makes that same decision out of discretion, what are they being discreet about? This is a concealment of something: we are throwing a veil over the unspeakable truth in the woman’s story. It is clear that this truth lies in her sguardo consapevole and her wordless gesture when she is asked why she killed her father. The implication here, I think, is that the intensity and ‘familiarity’ of the stabbing suggest that her father had sexually abused her, that she avenged herself by killing him, and that this explains why she was acquitted in court.

Antonioni calls this verità a ‘tragic irony,’ a type of truth that contradicts our expectations. The phrase suggests the tragic dramatic irony of Homo Faber, in which the audience and narrator possess a knowledge that the protagonist does not, but in which the incest itself is also framed in ironic terms. It is ironic that Walter Faber, the great man of science, cannot put two and two together to figure out that Sabeth is his daughter. It is ironic that his attempt to recover his lost youth results in his discovery that he is a father, and in the destruction of his own progeny. The deepest irony in Frisch’s text is that by ‘loving’ Sabeth he unwittingly abuses and destroys her.

Frisch said that his novel turned into a story of incest more or less by accident:

Not until I went on writing the part where [Sabeth] starts talking about her mother did I realize: this story is headed toward incest. My first reaction was to break it off. The book is bungled. The two stories don’t mesh. Besides, I don’t understand anything about incest.21

There is a remarkable overlap, here, with Antonioni’s claim of indifference with regard to the theme of incest, and with his decision (in ‘The girl, the crime’) to abandon the film he was trying to make. Frisch is drawn to the theme of incest, but this instinct makes him want to stop writing, but then he finishes the novel anyway, but then he feels he ‘bungled’ it because he understands nothing of the topic he chose to focus on.

In Volker Schlöndorff’s film of Homo Faber, the relationship between Walter and Sabeth – which in the novel was recounted in Faber’s cold, analytical, elliptical style – is filmed in a more conventional romantic mode, and both characters (especially Sabeth) seem reduced and simplified. Moreover, the film struggles to reproduce the hallucinatory feeling that infuses the original text. When Faber’s plane crashes in the desert, slow-motion and blurring effects give the sequence a slightly dreamlike feel, and billowing red dust is superimposed on the image for a few seconds, but the blue tint feels like a familiar and obvious cinematic technique for suggesting night-time. We get no sense – as we do in the encounters with landscapes in L’avventura, Red Desert, or Zabriskie Point – that this place and its colours and textures will resonate through the rest of the story. This desert really does just seem like a desert, as do the other (very beautifully filmed) international locations through which Sam Shepard wanders.

The chilling existential drama of the novel is replaced with a delicately erotic travelogue that seems designed to please and even titillate the audience. This fatal flaw is reflected in contemporary reviews. Vincent Canby argues that

Because [Julie] Delpy [as Sabeth] is a most attractive actress, the love affair takes on such weight and meaning that the inevitable revelation seems an arbitrary intrusion by a doomily schematic plot. It also seems to be worlds away from the world in which the film was made. […] [The film’s] tale of fate and predestination seems, at last, to be not timeless but absurd.22

Roger Ebert finds the incest theme similarly out of place:

[I]n a way the possibility of incest is the least interesting thing about this movie, even though the screenplay treats it as the most important. […] [I]t’s a shame all those contrived plot points about incest got in the way of what was otherwise a perfectly stimulating relationship. This is a movie that is good in spite of what it thinks it’s about.23

And as Adrian Martin points out, the reduced version of Sabeth we get here is little more than ‘a wispy projection of a tired and trite male fantasy.’24 Canby and Ebert seem more invested in that fantasy – the ‘weight and meaning’ of this story of a middle-aged man having a ‘perfectly stimulating relationship’ with a ‘most attractive’ 21-year-old – but all three critics, and the film itself, are arguably drawing attention to something (an investment in the Walter/Sabeth relationship) that was present in the original text. Max Frisch’s final partner was, after all, the daughter of his former mistress, and Schlöndorff thought she was clearly the inspiration for the character of Sabeth.25 This is the queasiest ‘irony’ of the incest plot: that the incestuous relationship not only contradicts expectations, but also fulfils a suppressed desire. Perhaps, contrary to Hanna’s reassurances, Walter failed to put two and two together precisely because he knew Sabeth was his daughter. Charles Helmetag’s summary of Homo Faber’s plot is, I think, reductive and sanitised:

An engineer who deserted his pregnant sweetheart indulges in the improbable fantasy that he can repeat the student romance at age fifty. Eventually the physical attraction for the twenty-year-old girl is mixed with and replaced by a father’s affection for his daughter.26

The more challenging implication, in the novel and the film, is that there is no ‘replaced by,’ only an uncomfortable mixture, which reveals something about Walter Faber. It is, as he says in his summary of Hanna’s verdict on these events, ‘a mistake that is part of me (?), like my profession, like the rest of my life.’27 In Hans Bänziger’s reading, Faber ‘attempted to live without death, was not capable of aging, dealt with life as an addition rather than as a contour,’ and his story exposes ‘the connection between technology, lack of maturity, and incest.’28 Incest is thus associated with the mindless pursuit of progress and novelty, with a refusal to acknowledge the relatedness of things and people. A more faithful adaptation of Homo Faber might have resembled an Antonioni film. Rather than being caught up in the aesthetic pleasures of the on-screen love affair (who roots for any of Antonioni’s couples?), critics would find the scenes between Walter and Sabeth cold and alienating, as though something obscurely terrible were happening between them. Rather than finding the incest theme a distraction, critics would read it as integral to the film’s exploration of ‘sick Eros’ in post-war Europe.

When Antonioni alludes to incest, it is always with the same pointed vagueness as in ‘The girl, the crime’, but also with the same association of incest with abuse and trauma (rather than with the sense of wish-fulfilment we find in The Man Without Qualities and Homo Faber).

When Anna’s father, in L’avventura, sees that his missing daughter was reading both Tender is the Night and the Bible, he ignores the former and focuses entirely on the latter, as though Fitzgerald’s novel contained something he did not want to acknowledge. We may remember his tense conversation with Anna at the start of the film, filled with unspoken sentiments, ostensibly revolving around the question of Sandro (and his unsuitability) but hinting at a deeper problem in this father-daughter relationship. Perhaps the story of Nicole Diver’s schizophrenia, stemming from her having been raped by her father, resonates with Anna’s anger towards her own father (whether or not this has to do with incest as such).

There is clearly a sexual dimension to Anna’s feeling of dislocation from the world and her decision to run away. She tells Sandro she does not feel him, he counters by reminding her of their sexual encounter the previous day, she angrily asks him why he has to sporcare (‘dirty’) everything…and then she disappears.

Anna is trying to express the sense of traumatised dissociation she experiences in her would-be intimate relationship with Sandro, especially when they have sex. Sandro casually, jokingly dismisses all this. His point of view is: ‘We had sex, it was good, it’s not a big deal, don’t think so much about whether you “feel” me or not.’ Anna experiences this as a betrayal so profound that it not only ends the relationship, it ends her relation to all people and things. That copy of Tender is the Night lurks in Anna’s luggage, like the copy of Homo Faber on Corrado’s bedside table: a clue, not necessarily to literal incest, but to the reality of sexual trauma and its long-term effects.

After Claudia hands the two books to Anna’s father and he sees only the Bible, insisting that a person reading this would never commit suicide, Claudia looks at him without speaking. Her expression is weirdly appalled, as though she feels that Anna has just been betrayed in some way. The moment is not unlike Anna’s appalled response to Sandro’s joke. Claudia walks away in tears, wearing Anna’s shirt (which Anna had secretly placed in her bag, perhaps as a clue to the deliberateness of her disappearance) and clinging to Tender is the Night. She leaves the Bible with Anna’s father; that book has nothing to do with the friend Claudia has lost.

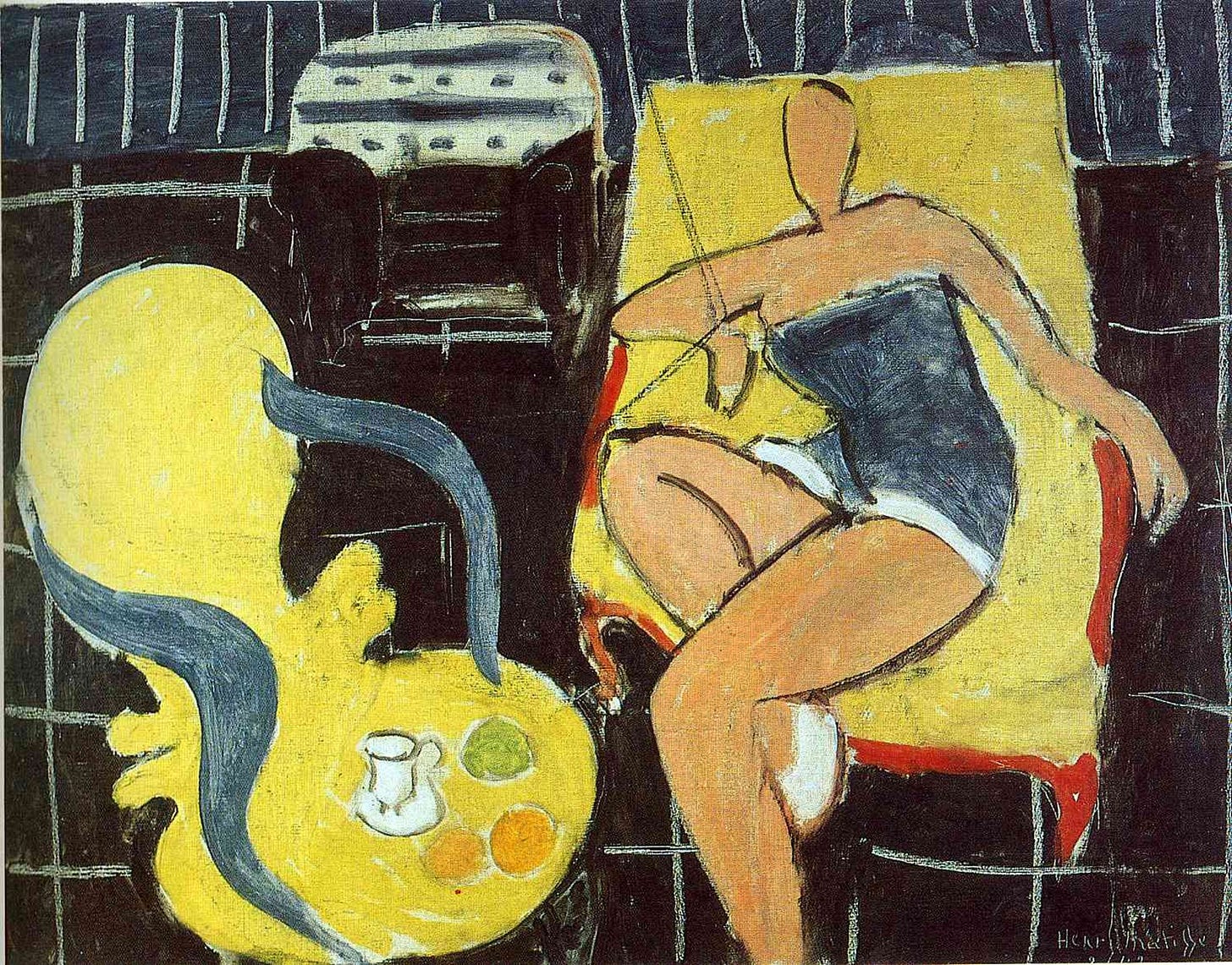

The Bible cover shows an image of the Annunciation – an angel telling a woman that she has magically become pregnant without having had sex – while Tender is the Night shows Matisse’s Dancer and Rocaille Armchair on a Black Background.29

Matisse’s lone human figure could be used as an illustration of Nicole or of Anna. She reclines in a state of languid noia, the chair next to her conspicuously empty (she does not want company), her features blank as though she has deliberately effaced herself (she confronts the viewer with her own absence), the black background belying the vibrancy of the foreground colours. If the dancer’s costume marks her as an aesthetically pleasing object of the male gaze, this effect is subverted by her own faceless-ness, which constitutes a sguardo consapevole like the one in ‘The girl, the crime’, somehow eloquent and opaque at the same time.

In Identification of a Woman, the thugs who are trying to frighten Niccolò away from Mavi turn out to have been hired, not by a jealous lover, but a man who has just revealed himself as her biological father. Mavi tells Niccolò that she always felt an instinctive revulsion towards this man without knowing why, implying that this revulsion is now explained by the realisation that he is her father.

This might seem counter-intuitive – wouldn’t we expect her to have an instinctive love for her own father? – but her revulsion is presented as though it were self-evident. Of course she would hate this man, after all he is her father. As in Tender is the Night, there is a sense that Mavi’s familial relations contain some mysterious clue as to why the story’s male protagonist cannot sustain a connection with her. Niccolò tries to ‘identify’ the truth behind Mavi’s inaccessibility, but in the process he ends up abusing and harassing her himself (see Part 39). Like the director in ‘The girl, the crime’, he ultimately backs away from the relationship and the film that might have evolved from this ‘identification of a woman.’

Both directors, though, and the women they encounter, are fictional characters in films that have been made – by Antonioni. ‘The girl, the crime’ was filmed as a segment in Beyond the Clouds, replete with a creepy sex scene between the director and the young woman who has murdered her father. These scenes, like the ones in Schlöndorff’s Homo Faber or the final sex scene between Niccolò and Mavi in Identification, are accompanied by schmaltzy romantic music. In each case, this artistic choice seems discordant, whether because we are watching father-daughter incest, because Mavi is just about to leave Niccolò (without saying goodbye) after their traumatic experience in the fog, or because this woman having sex with an older man has just explained how she murdered her father. In each case, the effect of the schmaltzily-scored love scene is something like that of the pink-washed room in Red Desert. We sense that something dark is being artificially brightened.

The reference to Joyce at the end of ‘The girl, the crime’, retained in the voiceover narration in Beyond the Clouds, opens up another kind of irony. Everything becomes clear in this sunlight, says the director, but then he calls this light ironic and compares it to Joyce’s snow which falls ‘over all the living and the dead.’ On the one hand it is illuminating and clarifying; on the other it is a concealing blanket that elides all distinctions, foreshadowing our ‘last end’ and the disintegration of all people, objects, and relations (see Part 24 for more discussion of ‘The Dead’). Like the woman’s silent gesture, or this story’s elusive hints at the verità beneath the surface, this is an ironic or even paradoxical revelation-through-concealment.

As the director in Beyond the Clouds offers his reflections in voiceover, he looks offscreen, at something that is not illuminated in these wide shots of picturesque locations, but that will always remain outside the frame. He is like the man at the end of ‘The event horizon’, visiting the site of the crashed plane, who ‘lets his eyes pan around and then up, to look at the clouds. Beyond the clouds.’30 This act of communing with the infinite beyond is likened to the encounter with death, but also with the ‘truth’ of the patricidal woman’s look of awareness. However, there is a distinction between these overlapping secrets: mortality and infinity are un-representable because they are unknowable; what happened between this woman and her father is left out of the film by choice, per discrezione.

Speaking of the living and the dead, this phrase (i vivi e i morti) is also used, in La notte, to encapsulate Giovanni’s disturbing encounter with the young woman in the hospital. On his way out after visiting his terminally ill friend Tommaso, Giovanni is approached by a wild-eyed young woman who pulls him into her room and closes the door. She stands with her back to the bare white wall. Giovanni inspects her.

She then tries to initiate a sexual encounter, as he reciprocates with a mixture of amusement, desire, and fear. On her bed, she bites him and looks at him furiously, but he continues to kiss and embrace her. We get the sense that Giovanni is taking advantage of this vulnerable patient, though he is frightened by what this entails in practice. He seems guilty and embarrassed when the nurses suddenly enter the room. They restrain the woman on the bed, slapping her violently as she tries to escape. An image of the Madonna and Child hangs on the wall.

Recounting this experience to Lidia afterwards, Giovanni describes it as spiacevole (unpleasant), saying that he felt as though the horrifying expression in the woman’s face had been provoked by him – that is, as though he bore some responsibility for her condition. Lidia casually suggests turning this experience into a story called I vivi e i morti, ostensibly distinguishing the dying Tommaso from the vivacious young woman, but perhaps also (as in ‘The Dead’) blurring these distinctions.

Lidia feels dead in her dead marriage to her dead husband. Tommaso, though dying, reminds her how alive she once felt. She also envies the young woman for her ‘irresponsibility,’ that is, for her freedom from the ties of convention, respectability, and relationships like Lidia’s with Giovanni. But what is most striking here is that Giovanni responds to his traumatic encounter as though it were totally unfamiliar and alien, whereas Lidia already seems to have come to terms with it. Something happened in that hospital room that she understands very well, but that Giovanni finds incomprehensible.

This scene may have been inspired by a passage in The Man Without Qualities when Clarisse visits the local mental institution and finds herself being won over by the ‘insane’ delusions of one of the inmates:

[I]n some way she lost control over her thoughts, new patterns took shape, their outlines looming from mist. […] Clarisse was as stunned by this slithering transformation as if something were slipping away from her; she impulsively reached out to the miserable creature with both arms, and before anyone could interfere, the patient leapt to meet her: he cast off his bedclothes, knelt at the foot of the bed, and began to masturbate like a caged monkey. ‘Don’t be such a pig!’ the doctor said quickly and sternly, while the attendants instantly grabbed the man and his bedclothes and in a flash reduced both to a lifeless bundle on the bed. Clarisse had turned dark red. She felt as dizzy as when the floor of an elevator all at once seems to drop away from under one’s feet.31

This loss of control, of one’s own thoughts, and of the ground beneath one’s feet, accompanied by a sense that strange shapes are emerging from the mist, brings us back to Giuliana’s symptoms. An encounter with a figure in a clinic (with whom one feels a connection, with whom one might even identify) suddenly becomes terrifying – becomes, in fact, a scene of sexual trauma. The spectacle of the madman or madwoman held down on a bed, beaten by the attendants, has the force of an epiphany, a showing-forth of some horrible truth about life that normally remains hidden from the eyes of respectable people. This truth can be repressed (as it is by Giovanni) or processed (as it is by Lidia and Clarisse).

Corrado’s rape of Giuliana is like this as well. Murray Pomerance quotes an interview in which Antonioni said that ‘The love scene in Red Desert has 47 shots in it, but only seven have [Richard] Harris in them.’32 Although Harris had been present for the location shoot in the hotel, he had left the production by the time of the studio-bound shots in that scene: the hallucinatory images, the writhing bodies on the bed, in short all the most intimate moments that constitute the sex act itself. Those moments, which critics so often read as ‘love-making,’ have a distinctly unreal quality. They are a kind of lie, culminating in the lie of the pink room, clearly constructed in the studio, from which Giuliana runs away, back into the verità of the real-life location.

The truth about this encounter has been hinted at and alluded to, but rendered vague and obscure by editing, set decoration, and other kinds of cinematic manipulation. Giuliana, though, has seen that truth, and she calls it what it is. Standing against the bare white wall of her shop, she is like the young woman in La notte, and Corrado is like Giovanni, disturbed by the encounter, unwilling to come to terms with what he sees, eager to distance himself from any suggestion of sexual trauma (especially if he bears some responsibility for it).

Like Sandro talking to Anna in L’avventura, Corrado tries to dismiss Giuliana’s fears and get her to see their encounter in more casual, neutral terms, to be satisfied with that vague montage of movie love-making and not think too hard about the feelings of distress, coercion, or dissociation that lay behind it. Like Anna, Giuliana sees this as a betrayal. There are so many terrible things that no one will look at or talk about, especially when they have to do with death or sex. Corrado’s sullen exit into the shadows, after he has raped Giuliana and told her not to think about it, is an embodiment of this culture of denial.

Next: Part 45, The harbour.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 494

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 19

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (Milan: Feltrinelli, 2005), trans. Aloisio Rendi (1959), p. 20

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 21

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 42

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 46

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 73

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 178

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 207

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), pp. 15-16

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 157

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 206

Youngman, Paul A., ‘Cybernetic Flow, Analogy, and Probability in Max Frisch’s Homo Faber’, in A Companion to the Works of Max Frisch, ed. Olaf Berwald (Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2013), pp. 140-155; p. 148

Butler, Michael, ‘Identity and authenticity in Swiss and Austrian novels of the postwar era: Max Frisch and Peter Handke’, in The Cambridge Companion to the Modern German Novel, pp. 232-248; p. 238

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 94

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 50

‘Appunto per “Deserto rosso” e riflessioni incompiute su incesto in letteratura e sulla filosofia’, 8D239b., ArchivioAntonioni

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The event horizon’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 1-10; pp. 4-5. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘L’orizzonte degli eventi’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 3-14; p. 7

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The girl, the crime…’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 79-86; p. 85

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The girl, the crime…’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 79-86; p. 86. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘La ragazza, il delitto…’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 91-100; pp. 98-99. Arrowsmith adds another adjective, ‘domestic’, which is not in the original text; see Part 16 for more comments on this. Arrowsmith’s translation is used verbatim in Beyond the Clouds.

Schlöndorff, Volker, ‘The Last Days of Max Frisch’, New York Times Book Review (05 April 1992)

Canby, Vincent, ‘Review/Film; A Variation on the Oedipus Theme’, The New York Times, 31 January 1992

Ebert, Roger, ‘Voyager’ (review), (29 May 1992), rogerebert.com. The film is often known as Voyager, especially in English-speaking markets.

Martin, Adrian, ‘Voyager’ (review), (November 1993), adrianmartinfilmcritic.com

Schlöndorff, Volker, ‘The Last Days of Max Frisch’, New York Times Book Review (05 April 1992)

Helmetag, Charles H., ‘Volker Schlöndorff’s “American” Film Adaptation of Max Frisch’s “Homo faber”’, Monatshefte 87.4 (1995), pp. 446-456; p. 452

Frisch, Max, Homo Faber (London: Penguin, 2006), trans. Michael Bullock (1959), p. 178

Bänziger, Hans, ‘Frisch as a Narrator’, in Perspectives on Max Frisch, ed. Gerhard F. Probst and Jay F. Bodine (Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1982), pp. 43-74; p. 62

Matisse, Henri, Dancer and Rocaille Armchair on a Black Background (1942), private collection; image taken from artchive.com

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The event horizon’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 1-10; p. 10

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), pp. 1411-1412

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 109