Everything That Happens in Red Desert (31)

Alienation and loneliness

Near the start of Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers, Bertrand meditates on the relationship between progress and emotions:

[O]ur feelings always lag half-a-century or a full century behind our actual lives. One’s feelings are always less human than the society one lives in. Just consider that a Lessing or a Voltaire accepted without question the fact that in their time men were still broken on the wheel – a thing that to us with our feelings is unimaginable. And do you imagine that we are in a different case? [...] [H]ow completely imprisoned we all are in conventional feeling. But feelings are inert, and that’s why they’re so cruel. The world is ruled by the inertia of feeling.1

This chimes very strongly with Antonioni’s comments, in his Cannes statement about L’avventura (previously discussed in Part 19), about technology outstripping morality:

Man is quick to rid himself of his technological and scientific mistakes and misconceptions. Indeed, science has never been more humble and less dogmatic than it is today. Whereas our moral attitudes are governed by an absolute sense of stultification. In recent years, we have examined these moral attitudes very carefully, we have dissected them and analysed them to the point of exhaustion. We have been capable of all this, but we have not been capable of finding new ones. We have not been capable of making any headway whatsoever toward a solution to this problem, of this ever-increasing split between moral man and scientific man.2

We adhere mindlessly and, as Broch might say, inertly to old conventions, but the disjunction between these conventions and the new world we live in creates a dangerous tension and a capacity for impulsive, spasmodic, destructive behaviour. Broch attempts a kind of long-sighted optimism: our feelings may lag behind our actual lives, they may seem inert, but even in the novel’s more cynical moments there is a sense that we are on a long road towards a better future, that we are always in the process of catching up to the more progressive society we have built around us. Antonioni’s perspective is different. As we saw in Part 30, he shares with Broch the sense that our old values and commonly held certainties are disintegrating, but he has little of Broch’s faith in the revolution and renewal that will follow in the wake of this disintegration. For Antonioni, it is as though the Lessings and Voltaires of his day have questioned, analysed, and (on a rational level) abandoned those outdated morals, and yet no progress has been made. He explores this issue primarily on the level of interpersonal relationships afflicted by alienation and loneliness, and it is on this level that we find the richest connections between Broch and Antonioni.

Another character in The Sleepwalkers, listening to Bertrand’s speech, considers its possible consequences:

With dismay Joachim saw the danger that like Bertrand one might begin to let everything slide if one began to transgress convention.3

Later, Joachim’s anxiety intensifies:

[I]n alarm he realized that he was no longer capable of grasping the evanescent, dissolving mass of life, and that he was slipping more and more quickly, more and more profoundly, into brain-sick confusion, and that everything had become unsure.4

Joachim’s fiancée, Elisabeth, experiences a similar crisis, but with less trepidation, more exhilaration, and a mysterious sense of melancholy:

[S]he could not understand her vague feeling of excitement, which yet seemed so strangely definite that it could almost be expressed in words: cut the world in two. It was not quite definite, certainly, yet a frontier line had been drawn, and what had once been indivisible, this closed world of hers, now fell asunder, and her parents stood at the other side of the frontier line. Behind all this was fear, the fear from which her parents wished to guard her as though their very life depended upon it; but the thing they feared had now broken in, strangely moving and exciting, and yet not in the least fearful. One could say ‘Du’ to a stranger: that was all. And it was so little that Elisabeth became almost sad.5

The impulse to break free of convention and dissolve the barriers between oneself and others is coupled with a fear of ‘letting everything slide,’ of ‘slipping into confusion.’ We are cutting the world in two – taking the coherent world our parents tried to hand down to us, and deconstructing it – but there is something strangely inconsequential about this revolutionary action. If one can split the world in two by saying ‘Du’ rather than ‘Sie,’ this means that what held the world together in the first place was frighteningly insubstantial. As we saw in Part 16, Giuliana surprises Corrado by addressing him with the familiar ‘tu’ (equivalent to the German ‘Du’), and this reflects her desire, in spite of convention and decorum, to connect and communicate with her new friend. But it also, perhaps, foreshadows the ultimate disintegration of that friendship as it slides into the more conventional form of an illicit affair. The relationship can so easily, so arbitrarily, go in either direction.

I discussed that sequence in the context of adultery dramas, arguing that Red Desert invokes many of the standard ‘love triangle’ tropes in order to subvert them, and Stephen Dowden sees Broch as doing something similar in his portrayal of Elisabeth’s relationship with Joachim. We recognise certain tropes from 19th-century realist fiction, and these evoke a ‘sense of pleasant familiarity’:

The reader knows the style and therefore has a general idea of how the plot ought to move forward. The expectation is that serious and touching conflicts will develop, that painful choices will be made, but finally that the order of things will be reaffirmed. Broch undermines these expectations by unmasking the terrible confusion that lies only slightly beneath the genteel surface of [Joachim’s] stiff uniform and polished manners.6

In L’avventura, we know how the plot ought to move forward, and no doubt that original Cannes audience was frustrated, in part, because they could see how the central love triangle might develop in more conventional and satisfying ways, and instead found themselves confronted with the ‘terrible confusion’ that lies beneath the characters’ complacent fulfilment of their narrative destinies. The ease with which Claudia falls in love with Sandro, a near-stranger, and the mixture of joy and sadness she experiences when this feeling breaks in on her, are closely related to Elisabeth’s crisis in The Sleepwalkers. ‘It’s sad,’ she says to Sandro, ‘I’m not used to it.’

Broch’s characters, like Antonioni’s, are often afflicted by loneliness as a result of their crises of values and feelings. One passage, an ostensibly intimate encounter between Joachim and Elisabeth, is infused with a hallucinatory mood of alienation:

Like yellow butterflies with black spots upon their serrated yellow wings, the ring of gas-jets blazed in the wreath of the chandelier over the black-silk catafalque on which Joachim still sat motionless with his body stiffly inclined and his knees bent, and the white-lace covers on the black silk were like copies of deaths’ heads. Into that frozen stillness dropped Elisabeth’s words [...] [T]he solitude prescribed for her and Joachim now began to encompass them, and froze the room, in spite of its intimate elegance, into a more complete and dreadful immobility; as they sat motionless, both of them, it seemed as if the room widened around them; as the walls receded the air seemed to grow colder and thinner, so thin that it could barely carry a voice. And although everything was tranced in immobility, yet the chairs, the piano, on whose black-lacquered surface the wreath of gas-jets was still reflected, seemed no longer in their usual places, but infinitely remote, and even the golden dragons and butterflies on the black Chinese screen in the corner had flitted away as if drawn after the receding walls, which now looked as if hung with black curtains. The gas-lights hissed with a faint, malicious susurration, and except for their infinitesimal mechanical vivacity, that jetted fleeringly from obscenely open small slits, all life was extinguished. [...] [Elisabeth] went on speaking in the emptiness, adding in the same breath, that yet was not a breath at all: ‘I will be your wife, Joachim,’ and was herself uncertain whether she had said it, for Joachim sat in unchanged stillness with his body inclined, and made no answer. No sign was given, and although it lasted no longer than the dulling and glazing of an eye, the tension was so charged with uncertainty and nullity that Elisabeth said again: ‘Yes, I’ll be your wife.’ [...] With a great effort he tried to bend towards her; he barely succeeded, but his half-bent knee actually did touch the ground; his brow, beaded with cold sweat, inclined itself, and his lips, dry and cold as parchment, brushed her hand, which was so icy that he did not dare to touch her finger-tips, not even when the room slowly closed in again and the chairs resumed their former places.7

This astonishing description conveys a sense of time and space dilating and contracting in response to the characters’ emotional and psychological conditions. The effect is distinctly cinematic, as though we were seeing this room and its contents through different, distorting lenses. Broch uses something like a montage technique to transform the meanings of the objects that surround Joachim and Elisabeth. The gaslight resembles butterflies, then the white lace on the sofa resembles death’s-heads (perhaps an association with death’s-head moths after the butterfly image), then the various decorative creatures flee from the deathly cold that envelops the room, and the whispering of the gas-jets becomes ‘malicious,’ the slits from which the gas emerges ‘obscenely open.’ Everything is alive and embodied, but at the same time afflicted with a funereal lifelessness. Of particular note here is Broch’s commentary on what happens to sound and speech in this claustrophobically expansive space. The air grows so cold and thin that it can barely carry a voice, and when Elisabeth speaks she is unsure whether she has spoken or not, partly because Joachim remains still and unresponsive. When the characters do come into physical contact with each other, they are feverish and sweaty (as though dying), dry and cold like parchment (as though newly dead), or colder still like ice (as though long dead).

Dowden notes the interdependence between eros and thanatos (death) in the culture from which Broch emerged, and his exploration of the different ways in which sex can be conceived: as a kind of ‘time-denying […] nihilistic self-gratification’ or as ‘an affirmation of temporality […] in harmony with time’s forward motion.’8 Dowden sees Joachim’s relationship with Elisabeth as exemplifying how ‘convention strives to contain the temporal threat of eros and death within artificial boundaries,’ but the intimations of death and eroticism in these characters’ interactions show that those temporal threats cannot be contained:

Like death, sex belongs to the elemental part of life that largely escapes convention and is therefore a threat to Joachim, who seeks refuge in the familiarity and clarity of convention.9

We see a couple trying to play out the typical scene of ‘the engagement’ within the setting of a respectable drawing room, but they seem beset on all sides by phantoms of sex and death. These elemental forces eclipse the tropes and conventions by which the characters are half-heartedly trying to live, plunging the scene into a kind of metaphorical darkness: the bright things all withdraw and the room suddenly appears to be hung with black curtains.

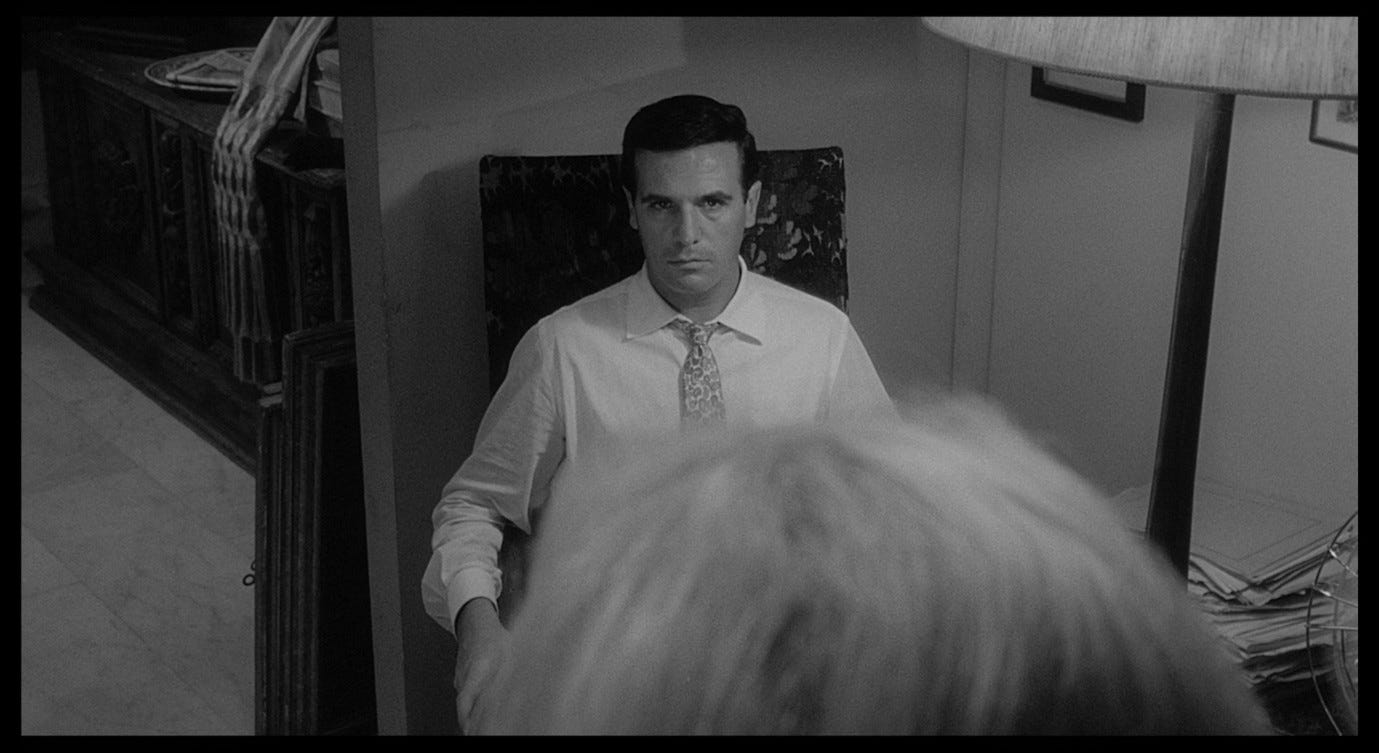

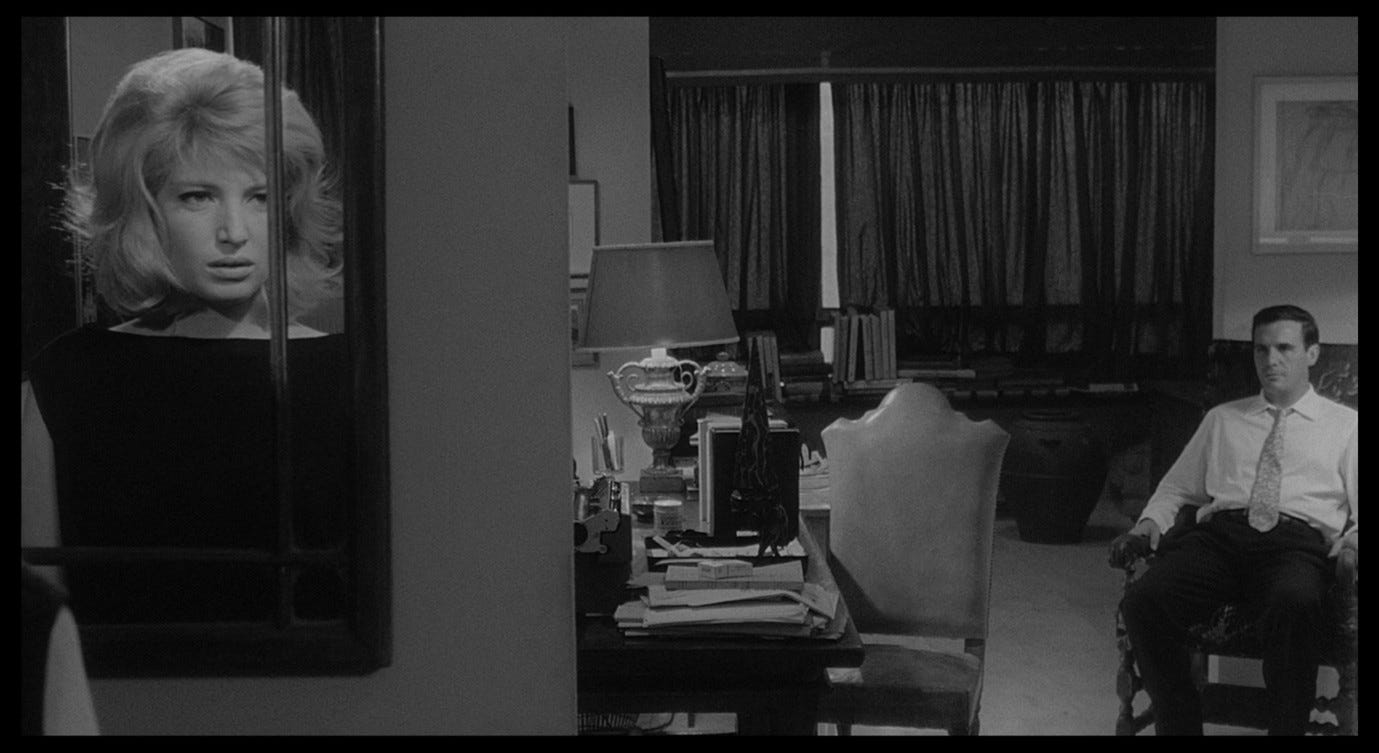

In the opening scene of L’eclisse, Riccardo’s living room takes on a sinister life of its own, in the context of a break-up rather than an engagement. The first shot of the film is hard to make sense of at first. We see a desk-lamp surrounded by books and pens, and lying along the top of a row of books is an unidentifiable white object. As the camera pans right, the white object turns out to be Riccardo’s elbow and forearm.

His wrist is obscured by a marbled pyramid-shaped sculpture whose summit rises out of the frame. This object seems to divide the inanimate part of Riccardo (which belongs to the earlier composition) from the animate part (which belongs to this new composition), but its identical sloping surfaces also seem identified with him – whichever perspective you look at Riccardo from, he seems just as flat and inhuman. The panning movement brings an oscillating fan into the frame: the fan turns its face in one direction then another; Riccardo’s face similarly changes position while the rest of him remains inert.

The low, surging-and-subsiding hum of the fan reminds me of the line in The Sleepwalkers about the gas-lights hissing with a ‘faint, malicious susurration,’ their ‘infinitesimal mechanical vivacity’ constituting the only sign of animation in the death-shrouded room. Riccardo’s lamp, his books, his sculptures, and all his other household objects come to mean something different when juxtaposed with this disintegrating relationship.

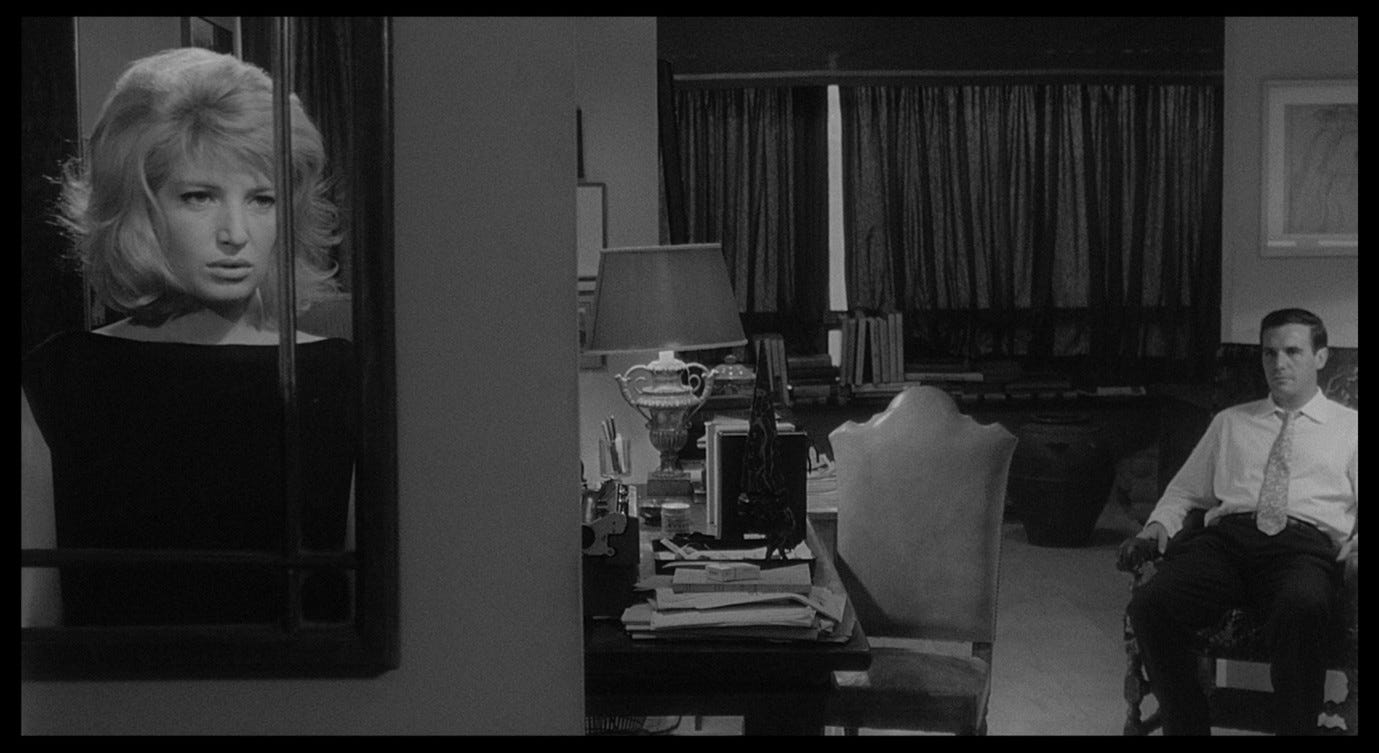

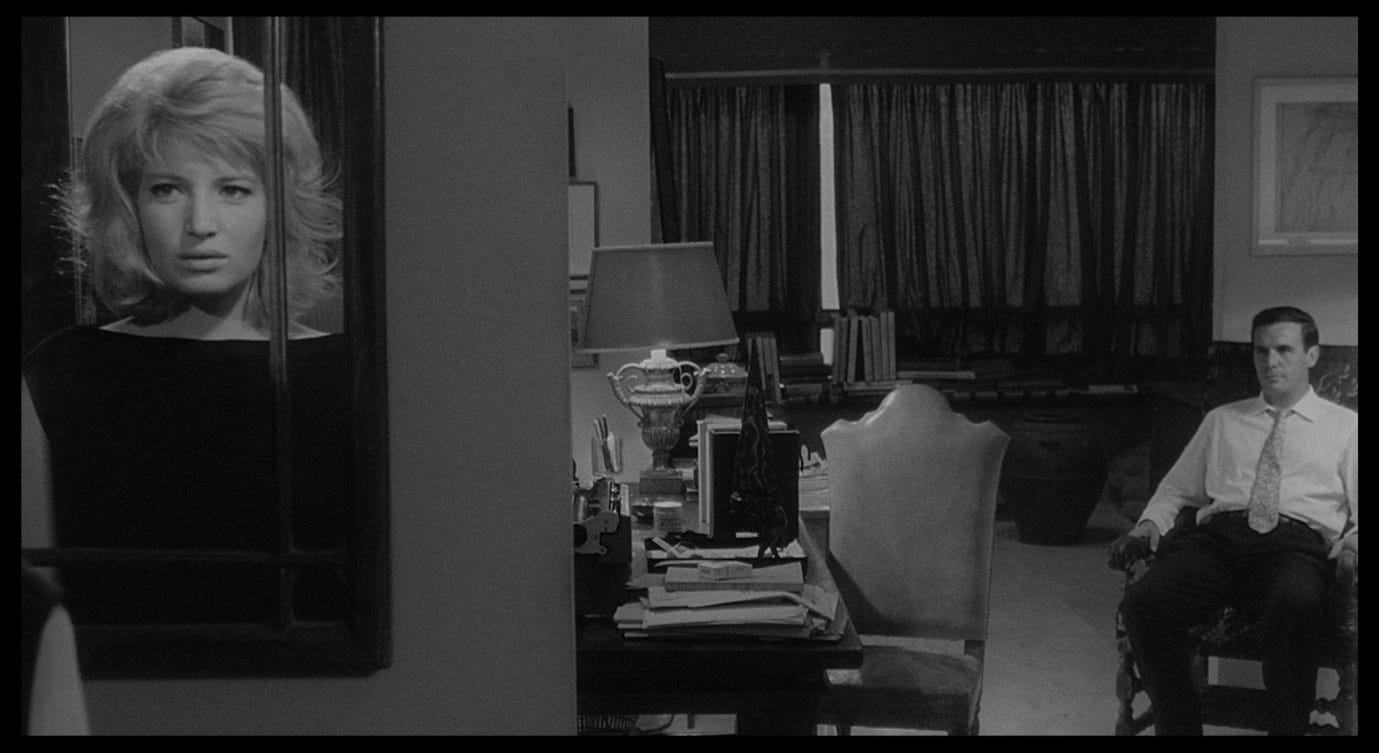

A minute later, Riccardo becomes even more inanimate and silent, like Joachim in The Sleepwalkers. Vittoria approaches him, staring in disbelief at his de-activated form, then backs away slowly.

Wanting to divert her eyes from this disturbing spectacle, she finds herself accidentally catching her own reflection in a nearby mirror, and looks helplessly from the mirror to Riccardo and back again. To escape from seeing either of these lifeless images, she turns her back to the mirror.

Her reflection mirrored not only herself but also something in Riccardo – she saw ‘Riccardo’ and ‘Vittoria’ side by side, made equivalent to each other – and now she takes the place of her own reflection, not only avoiding it but also acknowledging her identity with it: she is what appeared in that surface. As I argued in Part 20, Vittoria’s terror in this moment has much in common with Giuliana’s when she faces the inert figures in the fog.

Broch pictured a scene in which Joachim’s and Elisabeth’s pained consciousness of their rapidly changing world caused a transformation in their surroundings: the splitting apart of the world, in terms of social conventions, also triggers a splitting apart of every object within that world. The engagement – an affirmation of a social contract – is belied by the disengagement of those objects from their accepted identities and associations. For Riccardo and Vittoria, it is the break-up that is belied. Joachim seemed not to hear Elisabeth saying she would marry him, and Riccardo cannot take in Vittoria’s rejection; he sits there as though it had not happened, as though nothing had happened. Here, the objects conspire against the dissolution of the relationship, absorbing Riccardo and Vittoria into their inanimateness and silence, trapping them in their togetherness. This is one manifestation of the ‘eclipse’ referred to in the film’s title. As for Broch’s sleepwalkers, something has changed in the world of these people and cast a paralysing shadow over them, shutting out the light that normally gives their lives meaning.

In the engagement scene between Elisabeth and Joachim, verbal communication and bodily intimacy have become impossible, to the point that these two might just as well not be alive (as the death-focused imagery suggests). Life, in Broch’s conception, depends on the things that connect us to each other, and when those things break down we are as good as dead. In an earlier passage, the song of a canary momentarily resolves the tension between a group of people:

They gathered round it as round a fountain and for a few moments forgot everything else: it was as though this slender golden thread of sound, rising and falling, were winding itself round them and linking them in that unity on which the comfort of their living and dying was established; it was as though this thread which wavered up and filled their being, and yet curved and wound back again to its source, suspended their speech, perhaps because it was a thin, golden ornament in space, perhaps because it brought to their minds for a few moments that they belonged to each other, and lifted them out of the dreadful stillness whose reverberations rise like an impenetrable wall of deafening silence between human being and human being, a wall through which the human voice cannot penetrate, so that it has to falter and die. But now that the canary was singing not even Herr von Pasenow himself could hear that dreadful stillness, and they all had a feeling of warmth.10

The bird’s song is a ‘thin, golden ornament in space,’ echoing Broch’s insistence on the importance of ornament as a spatial phenomenon in an epoch’s style:

[W]hatever a man may do, he does it in order to annihilate Time, in order to revoke it, and that revocation is called Space. Even music, which exists only in time and fills time, transmutes time into space [...] And in this also can be seen the peculiar symptomatic significance of ornament.11

Music too is a kind of ornament that soothes our fears, specifically our fear of the ‘deafening silence between human being and human being.’ It makes us feel that we belong to each other, that there is a kind of ‘unity’ amongst us upon which the ‘comfort of our living and dying’ is established, and it not only moves between us and fills us up but also winds back to its source, like an ouroboros that defies the transience of earthly life. Loneliness, alienation, death, the passage of time – all these fearful things are suspended by the bird’s song.

It is interesting that the music also suspends the characters’ speech, not unlike the deathly cold of the encounter between Joachim and Elisabeth. Just as the ‘absolute zero’ towards which our mechanistic society is heading can figure both annihilation and renewal, so the sublime feeling of unity and oneness (one being the antithesis of zero) can also be a kind of eclipse. Elsewhere in The Sleepwalkers, Broch speaks of ‘freedom and loneliness’ as though they were interdependent, and of ‘the deepest community of the spirit into which that most profound loneliness must inevitably change.’12 Again, he tends to frame these seeming contradictions in optimistic terms, as a movement through alienation towards harmony, whereas in Antonioni the sense of harmony and community tends to dissolve back into a deeper loneliness.

Broch’s optimism comes through even more strongly in his later novel, The Death of Virgil, in which the dying poet argues with his master, the emperor Augustus, over whether he should be allowed to destroy the nearly-completed Aeneid. Feeling that no one understands his reasons for wanting to burn the poem, Virgil experiences a profound sense of alienation:

What passed back and forth between them now amounted to nothing, just empty words, or not even words any more, racing across an empty space that was no longer even space. Everything was an unbelievable nothingness, cut off and bridgeless. […] The many layers of existence had faded to an amorphousness beyond that of any emptiness; no lines were to be seen any more, not the faintest shadow of a line – where could one still find the means of recognition? […] ‘No more layers of existence…’13

Again, it is easy to recognise the premonitions of Antonioni here: Virgil’s despair at the empty not-even-words passing between him and his friend is like Vittoria’s in her near-wordless argument with Riccardo, and the fading of the ‘layers of existence’ into line-less amorphousness could easily describe the condition that plagues Giuliana. But something changes as Augustus becomes more combative, ‘hollering his complaints’ with a frankness of emotion that somehow restores the two men’s friendship:

[I]t seemed as if there were an invisible firm ground showing within the invisible realm, that firm invisible ground from which invisible bridges could be flung again, human bridges to humanity, chaining one word to another, one glance to another, so that word, like glance, should again become full of meaning, human bridges of meeting. […] Layer on layer of existence piled up under these scoldings, and the room which Caesar was furiously pacing was an ordinary earthly room once more, part of an earthly house and furnished with earthly furniture, an earthly thing in the light of late noon. And now one could even feel one’s way across the invisible bridge.14

‘Octavian, accept the poem!’ cries Virgil at the climax of this scene, recanting his desire to burn the Aeneid. If the bridge between him and this other person can be repaired and traversed, and if the room they are in can have its ‘layers of existence’ restored to it, then the poem may also convey some true perception of reality to the world after Virgil’s death. After uttering this cry, Virgil seems cured of the Giuliana-vision that previously tormented him, and the room undergoes a further transformation that reverses the effect of the engagement scene in The Sleepwalkers:

All the paperish pulp, the dull paper-like whiteness had disappeared from the atmosphere outside; the light shimmered over the landscape, almost ivory in color. […] [T]he brown timbered ceiling was again becoming the forest from which it had been taken, the laurel scent of the wreaths turned back into the most hidden shadows resting deep in the sun-covered leafy vales, misty with the trickle of the fountains, misty and soft like the tone of a mossy reed and yet firm-fast, yet oaken-heavy, and the breath of the inexplicable heart was that of mutual intuition.15

The product of industry – the constructed edifice – had before been alienated from its origins in nature, but now it is the forest from which the wood was taken, and the mist evoked by the laurel scent is firmly tied to something ‘firm-fast, oaken-heavy.’ It is as though Tintal’s green paint could truly retain a sense of the verdant forest it is meant to evoke (see Part 2).16

Though Virgil’s and Octavian’s hearts are ‘inexplicable,’ incapable of being explained or represented through language, yet the breath that passes between them as they speak contains ‘mutual intuition,’ a true understanding of each other’s true selves. This in turn renders their words ‘full of meaning’ and thus restores Virgil’s faith in the words of his own poem – and, by implication, Broch’s faith in the words of his own novel. The final line, as Virgil dies, describes his encounter with the ‘incomprehensible and unutterable […] word beyond speech.’17 Like the early 20th-century society which, as Broch saw it, was passing through a disintegration towards a state of ‘absolute zero’ in order to discover a state of redemptive renewal, so the relationship of one person to another, or of an artist with their work, will sink to a nadir of alienation before reclaiming a transcendent form of connectedness. Hannah Arendt sums up the novel’s overall effect:

Suspended between life and death, between the ‘no longer’ and ‘not yet,’ life reveals itself in that all-meaningful richness which becomes visible only against the dark background of death.18

Compare this with Antonioni’s famous comment about the layers of reality, spoken by the unnamed director in the final moments of Beyond the Clouds as he retreats into the darkness of his hotel room:

We know that under the revealed image there is another one which is more faithful to reality, and under this one there is yet another, and again another under this last one, down to the true image of that absolute, mysterious reality that nobody will ever see. Or perhaps, down to the decomposition of every image, of every reality.19

That last sentence is not in Beyond the Clouds, which I think is a shame, because it might have lent even more poignancy to the fade-to-black and then fade-to-blue in the end credits. Antonioni cannot even bring himself to maintain a faith in some form of reality that exists but will never be seen – he has to go one step further and imagine that it simply is not there, that the proposed investigation into the deepest layers of the image would only bring about a universal dissolution. In a perverse echo of Broch, this thought prompts him to reaffirm his faith in his art: ‘Therefore, abstract cinema would have its reason for existing.’20

As Virgil passes into the afterlife, he experiences

the merging of the outer with the inner face, always striven for, never attained, but now fully achieved by this final exchange: suddenly […] this man, who had hitherto been called Augustus, was seen from within, seen in that completely inner way usually reserved for the dreamer, the dream-lost, when he forgets his earthiness and – gaining perception through the dream – recognizes himself in the image of himself […] oh, unlosable is he who is seen from within in his nakedest wholeness.21

Here the image becomes the ultimate conveyor of reality, a vehicle for spiritual revelation that transcends ‘earthiness.’ This image is also – more importantly for our purposes – an enabler of human connections that are not only real but ‘unlosable,’ incapable of disintegration. The dizzying effect of the passage just quoted is to equate Virgil’s seeing of Augustus with his seeing of himself; knowing another from within means that you become them, and they become you. By contrast, the argument between Vittoria and Riccardo leads only to silence, and to an encounter ‘from without’ with Riccardo’s empty surface and Vittoria’s panicking reflection.

This contrast sums up the difference between Broch’s and Antonioni’s take on loneliness. For Broch, the value of a work of art (like a novel) is threatened by his sense of incommunicability, so the stuff of art – the words, the images – must communicate something real after all, must be made explicable even through their inexplicability. For Antonioni, the stuff of art – his images, the way they move and are edited together, the sounds that accompany them – must investigate that sense of incommunicability ever more closely and clearly, the final revelation ‘always striven for, never attained’ as Broch says, but without the consummation of ‘now fully achieved.’ The images strive towards abstraction and dissolution because, to put it in terms that bring us back to our main subject, abstraction and dissolution (not clarity and harmony) are the defining features of Giuliana’s experience.

Next: Part 32, Loneliness and childhood.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 830-838

‘A talk with Michelangelo Antonioni on his work’ in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; p. 33. The Cannes statement is quoted in full as part of this interview, and is also available on the Criterion website.

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 846

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 1979

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 1762-1767

Dowden, Stephen D., Sympathy for the Abyss: A Study in the Novel of German Modernism: Kafka, Broch, Musil, and Thomas Mann (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1986), pp. 45-46

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 2507-2532

Dowden, Stephen D., Sympathy for the Abyss: A Study in the Novel of German Modernism: Kafka, Broch, Musil, and Thomas Mann (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1986), pp. 37-38

Dowden, Stephen D., Sympathy for the Abyss: A Study in the Novel of German Modernism: Kafka, Broch, Musil, and Thomas Mann (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1986), p. 46

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 1278-1283

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 7172

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 11859

Broch, Hermann, The Death of Virgil (1945), trans. Jean Starr Untermeyer (Lebooks Editora, 2024), Kindle edition, pp. 411-412

Broch, Hermann, The Death of Virgil (1945), trans. Jean Starr Untermeyer (Lebooks Editora, 2024), Kindle edition, pp. 415-416

Broch, Hermann, The Death of Virgil (1945), trans. Jean Starr Untermeyer (Lebooks Editora, 2024), Kindle edition, pp. 417-418

Image posted by ebay.it seller ‘stems23’, item listed as ‘advertising Advertising 1967 TINTAL MAX MEYER’

Broch, Hermann, The Death of Virgil (1945), trans. Jean Starr Untermeyer (Lebooks Editora, 2024), Kindle edition, p. 513

Arendt, Hannah, ‘The Achievement of Hermann Broch’, The Kenyon Review 11.3 (1949), pp. 476-483; p. 482

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Preface to six films’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 57-70; p. 63. Cooper translates the last sentence as, ‘Or perhaps, not until the decomposition of every image, of every reality,’ suggesting a Broch-like gesture towards a revelation at the end of the world or the end of life. But the sentence uses the same ‘fino a’ construction as the previous one, which refers to the unveiling of successive layers of images: ‘Fino alla vera imagine’ means ‘Down to the true image,’ and then I think ‘fino alla scomposizione’ means ‘down to the decomposition.’ In other words, Antonioni is not imagining a time when someone will see that ‘true image,’ but rather imagining that peeling back these layers would not even reveal the truth but cause all images and realities to disintegrate. Italian text from Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), p. xiv.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Preface to six films’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 57-70; p. 63

Broch, Hermann, The Death of Virgil (1945), trans. Jean Starr Untermeyer (Lebooks Editora, 2024), Kindle edition, p. 471