Everything That Happens in Red Desert (34)

A story for Giuliana

In between her discovery that Valerio is paralysed and her discovery that he is faking paralysis, Giuliana tells her son a tale about a girl on a pink beach. This tale operates, like any good bedtime story, in a liminal space between waking and sleep, but the story is also deeply conflicted about its target audience. When Giuliana tells her demanding son that she has no stories left to tell, he asks her to repeat one from the day before: ‘The one about the kite.’ She suggests that he should have a nap instead, but then we cut directly to her telling a new story. Have we jumped to a later time in the day, after Valerio’s nap? Or does Giuliana change her mind and begin improvising in this moment? Is this the story Valerio hears when he wakes up, or is this how she puts him to sleep, with the mysterious song serving as a lullaby and the final blurry images signifying the moment when he nods off? Or is Giuliana simply telling a story to herself?

This is the kind of spatio-temporal disorientation that Red Desert has inflicted on us in previous scenes, through transitions that leave us unsure of where we are or how much time has passed. In this case, the effect underlines the dislocation between Giuliana and Valerio. For most of the ‘pink beach’ story, it is not clear whether Giuliana is speaking to her son or to herself. The island fantasy seems more like a space she retreats to in her own mind than a response to her son’s request. Only at the end of the story does a (very awake-sounding) Valerio interject with a question, and it is almost jarring to be reminded of his presence.

Robert Benayoun asked Antonioni to explain this scene, proposing two possible functions it might serve:

Did you conceive of Giuliana’s dream in order to create a blue-and-pink interlude in a film largely dominated by other colours, or in order to suggest nostalgia for a paradise of purity and harmony within a context of industrial waste and polluted waters?1

Antonioni replied:

Mainly for the latter reason, I imagine, though in fact I don’t know how the imaginative process works. In dramatic terms, I needed Giuliana to invent a new story, which she would tell her son and which, in reality, aims only to reassure Giuliana herself.2

I think this slightly overstates the case, because part of what makes this dream/story so interesting is that it begins with a scenario that could be tailored to Valerio’s needs, but becomes more obviously a story-for-Giuliana as it goes on.

Valerio’s request for a story about a kite may seem to be motivated by his (alleged) paralysis. Perhaps, Giuliana thinks, Valerio would like to identify with an object that has no legs and is un-grounded, but can fly freely in the air, like the helicopter he has just been playing with. In the original screenplay, the story of the kite was to have described

a kite whose flight is the collective venture of an entire village. As the craft ascends, the villagers unravel all their fabrics to provide the length of string required for it to reach the stars. The kite survives all manner of threats, both natural and man-made (lightning and missiles) so that the analogies to Giuliana’s own psychic state are not far to seek.3

Millicent Marcus thus reads this story too as being more ‘for Giuliana’ than ‘for Valerio,’ but it is not hard to see why he enjoyed it enough to request a repeat performance. Even once we realise that his legs are not paralysed, if we see his ruse as indicative of a desire for mechanical limbs (see Part 33), we can understand the kite-story as a fantasy of engineered omnipotence. The villagers, like the workers in a factory, devote all their labour and resources to making this impervious kite-rocket that can travel to the stars. The kite resembles the gyroscope designed to brave the roughest seas, which perhaps explains Giuliana’s reluctance to re-tell this story, given how left out she seemed to feel during the gyroscope demonstration (see Part 24).

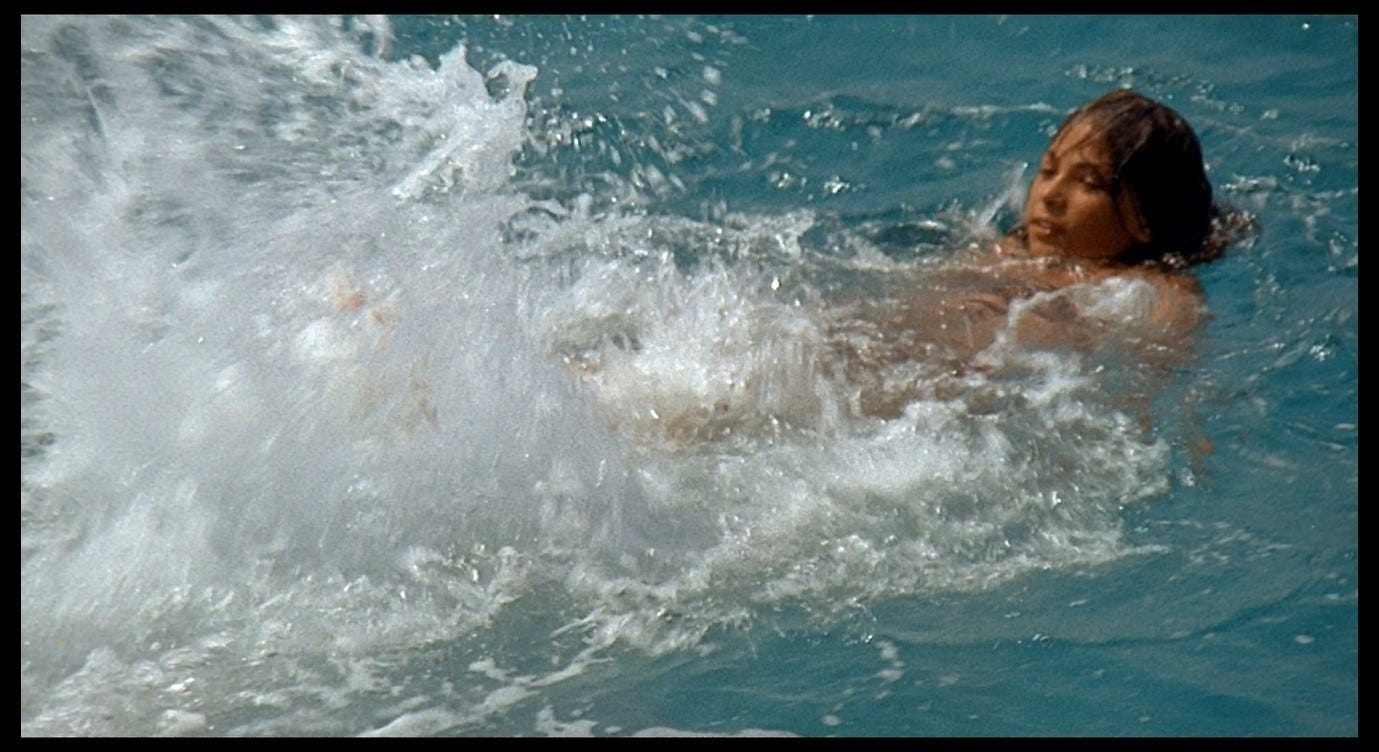

At the beginning of the island fantasy, only the girl’s head and shoulders are visible above the water, so that, like the kite, she appears to float freely without legs. The way she swims around the cove or runs over the sand is suggestive of lightness, mobility, and freedom.

The story also emphasises her solitary nature – she avoids adults and children alike – and this may speak to Valerio’s apparent self-sufficiency, which has (as it turns out) prompted him to give himself a day off, playing with his toys on his own. Giuliana has, so to speak, brought the kite-story down to earth and reined in the exploratory power of the gyroscope. Valerio, she supposes, will like this story of solitude and liberty, but it will not be so out-of-this-world that she will feel alienated from it.

The plot of this bedtime story, such as it is, involves the appearance of two mysteries in the young girl’s world: the ship devoid of people and the disembodied voice. Valerio has an enquiring mind that engages enthusiastically with the scientific toys his father gives him. For him, the modern world and its advances are there to be explored and investigated. He builds robots, carries out experiments, flies his helicopter, and plays with models of internal organs. In her story, Giuliana presents Valerio with a different type of mystery, a type that that cannot be unravelled through scientific inquiry but that instead elicits a sense of inexplicable wonder. She seems to acknowledge that there is something unsatisfying, even disturbing, about this when she comments (upon the appearance of the singing voice), ‘One mystery is fine; two is too many.’ Valerio asks, ‘But who was it who was singing?’, and the answer, as we will see in Part 35, has several possible meanings.

In this way, Giuliana caters to Valerio’s spirit of exploration, while at the same time trying to draw him away from the Ugo-world of tangible, observable phenomena, towards her world of mystery and uncertainty. When she first hears that Valerio is sick, but hopes that he might be exaggerating his symptoms, Giuliana tries to coax him from his bed by saying there is a beautiful ship outside, all painted white.

This is a somewhat romanticised description of the ordinary-looking grey/white ship we then see, by which one can only imagine Valerio would be angrily disappointed, but Giuliana is trying to appeal to her son’s interest in sea vessels (which we can infer from the chalk-drawing on the blackboard and the gyroscope demonstration). When she then introduces the mysterious ship into the story, she is again appealing to Valerio’s interests while attempting to reorient them: like the vision of the ‘all white’ ship in the docks, the one in the story is an object of wonder rather than a phenomenon to be studied empirically. It is best appreciated via the imagination rather than in plain sight.

Giuliana draws a distinction between the mysterious ship and the ones the girl is used to seeing. These ‘usual’ boats are part of the world she avoids, where ‘adults are frightening and children play at being adults.’ They are small, with matte-painted hulls, and move across the water in a quiet, orderly fashion, nearby and easily observable.

The mysterious visitor, ‘a real ship [un vero veliero]’ as Giuliana calls it, appears with the sound of a thunderous crashing wave, its hull gloss-painted in dark blue and red, and it is always too far away to be seen clearly.

It resembles a nineteenth-century sailing boat that would look out of place in the port of Ravenna in 1964.4 Devoid of people, it is a kind of ghost ship, piloted by invisible spirits – perhaps the same kind of invisible spirits who turn out to inhabit the rocks around the cove. The girl feels compelled to investigate this strange object, but as she gets closer the ship becomes more mysterious than ever. Finally, rather than subjecting itself to further study, the ship turns and sails away, and the questions it raises are never answered.

In the scene that precedes Giuliana’s story, she is visibly overwhelmed by anxiety over Valerio’s illness. She looks sleep-deprived, biting her nails and staring into space, and his demands seem impossible to fulfil.

As a children’s story, especially one aimed at Valerio, hers ultimately seems like a failure, born out of exhausted desperation: it creates a disturbing sense of mystery without any exciting revelations or satisfying pay-offs. Giuliana later says that Valerio ‘doesn’t need her,’ and the story she invents for him seems to be infected with this sentiment as well. Unlike Ugo, she cannot meet Valerio on his own level or show him anything he wants to see. Try as she might to appeal to his interests while drawing him closer to her own way of seeing the world, Giuliana cannot help telling a story that resonates with herself rather than with him. It is as though she were conscious of her son’s critical eye and were trying to explain herself to him, to express something that lies at the root of her condition: ‘I know you think I’m failing you, but this will make you understand...’

The first thing we learn about the girl in this story is that she is estranged from her own people. Adults (i grandi) scare her, and other children annoy her because they are always ‘playing at being adults.’ We can connect these sentiments with Giuliana’s own feelings about the frightening industrial complex built by the grandi of her world, and about her child who plays at being an engineer. As Murray Pomerance says,

Pretending to be grownups means, explicitly, capitalizing on resources, mobilizing the economy, producing wealth, exploiting nature, abandoning or utilizing art […] This world is boys’ work, Giuliana the price boys are paying for their progress.5

The girl in the story is luckier than Giuliana, because she has discovered ‘a little beach far from her home,’ a place of refuge where she can avoid the fearful aspects of her culture while acting her own age. Acting her own age means playing – the cove is a site of pure recreation for her – and not playing at being one of the adults. The girl’s activity, prior to the arrival of the ship, is noticeably aimless, without any ‘singleness of purpose,’ to use Hermann Broch’s phrase (see Part 30). She runs into and out of the water, she reclines on the beach, she watches the waves and the animals, and she leaves when the sun goes down.

Giuliana does not, I think, come across as being child-like or afraid of embracing adulthood. However, the plight of the young girl is an allegorical representation of Giuliana’s clash with the forces of ‘development’ and ‘progress’ that shape her world. The focus on recreation also chimes with Giuliana’s evident playful instincts, seen earlier in her humorous banter with Corrado and her high spirits during the daytrip sequence. In Part 19, I noted an instance of a familiar Antonioni trope, in which characters erupt with spontaneous joy before experiencing a sudden hangover, snapping out of their playful mood as though ashamed. Like the impulsive but miserable relationships these people engage in, their failed attempts at play are symptomatic of the malattia dei sentimenti that Antonioni is exploring. Giuliana’s story expresses this sickness in terms of children-playing-at-adulthood. She fantasises about a more authentically child-like recreational space where a person can be themselves, by themselves, without any hangover or sense of shame.

It must be said that some shots of the young girl – especially the ones where she is seen, from behind, removing her bra as she leaves the cove – are a little creepy, foreshadowing Antonioni’s tendency to leer at female characters in his later films. To some degree, the fantasy-cove sequence is pointedly un-erotic: part of the subtext here is that Giuliana lives in a world whose sexual impulses, like its industrial practices, are manifested in violent, exploitative ways, and she is fantasising about another world where she could escape from all that. Millicent Marcus emphasises this in her reading of the story’s prelapsarian overtones:

It is no accident that the protagonist of the fable is a prepubescent girl who has not yet suffered the fall into experience that will irrevocably exile her from the earthly paradise of her island retreat. This is Giuliana’s personal myth of Eden, a place where the primal unity between the self and the world has not yet been split asunder by guilty knowledge or willful rebellion against the natural order. The child and the environment live in happy concord, she obeying the rhythms of the sun, the rocks mimicking the smooth brownness of her flesh, and the mysterious song, half human and half wild, making literal the metaphor of harmonious coexistence.6

But as the fantasy goes on, and particularly as the rocks begin to resemble naked bodies, this can also be read as a story about Giuliana’s discovery of, or coming to terms with, her own sexuality and the role of sexuality in the world around her.

Later, when Giuliana says that ‘there is something terrible in reality,’ what Marcus calls ‘the natural order’ is part of that terrible something. Even the ‘concord’ between the individual’s rhythms and those of her environment will become a nightmare (and an overtly sexual one) of melded-together bodies in a flesh-like hotel room. In the fantasy-cove sequence, I do not think the camera crosses the line into actual ‘leering,’ but I do think the young girl plays a part in Red Desert’s complex (and in some ways problematic) exploration of Giuliana’s fear of the male gaze and of the camera-eye that objectifies her.

The girl on the beach acts freely and in accord with nature, behaving much like the animals around her and aligning her activity with the coming and going of the sun. In this place, ‘the sea was transparent,’ in contrast to the gruesomely opaque waters of the ruined fishing spot we saw earlier, or those of the Ravenna docks we will see later.

Giuliana’s narration continues: ‘Nature had such beautiful colours, and nothing made noise [La natura aveva dei colori cosí belli, e niente faceva rumore].’ She lingers over the word niente, savouring this fantasy of a world in which machines are not constantly humming and whining all around her. The natural colours too offer a stark contrast to the artificially colour-coded environment in which Giuliana lives. Sam Rohdie notes that Giuliana’s ‘real world’ is constantly shifting and blurring around her, whereas ‘when she creates a fantasy, an unreal world, it is in Technicolor with everything clear and precise and sharp.’7 In other words, we know this is not the real world because it seems so real, so natural.

As soon as this sequence begins, we realise that we have passed into a different reality, an Edenic eco-fantasy of nature un-compromised by humanity. This is one of those past-tense stories that begins with the word C’era, set in a time when nature had beautiful colours. The look of this sequence is so different from the rest of Red Desert that we feel we are watching the wrong film: in the real Red Desert, Giuliana tries to reproduce natural colours like celeste and verde in her shop, but cannot stop the walls from looking like artificial surfaces with artificial tones applied to them.

Just as her ambitions for that shop seemed impracticable and even indecorous (as Ugo said), so there is a sense of futility in her tale of the pink beach, perhaps even a sense (on Giuliana’s part) that she shouldn’t be filling Valerio’s head with such nonsense. She is harking back to childhood and to a lost world, conjuring up a fantasy that does not belong in this film. Giuliana is aware of this, just as she is aware that she will never open that ceramics shop on the Via Alighieri. She also knows that she cannot bring this bedtime story to a satisfying conclusion. Its natural colours and its tone of escapist nostalgia immediately mark it as unsustainable, so Giuliana cannot help but deconstruct it from within.

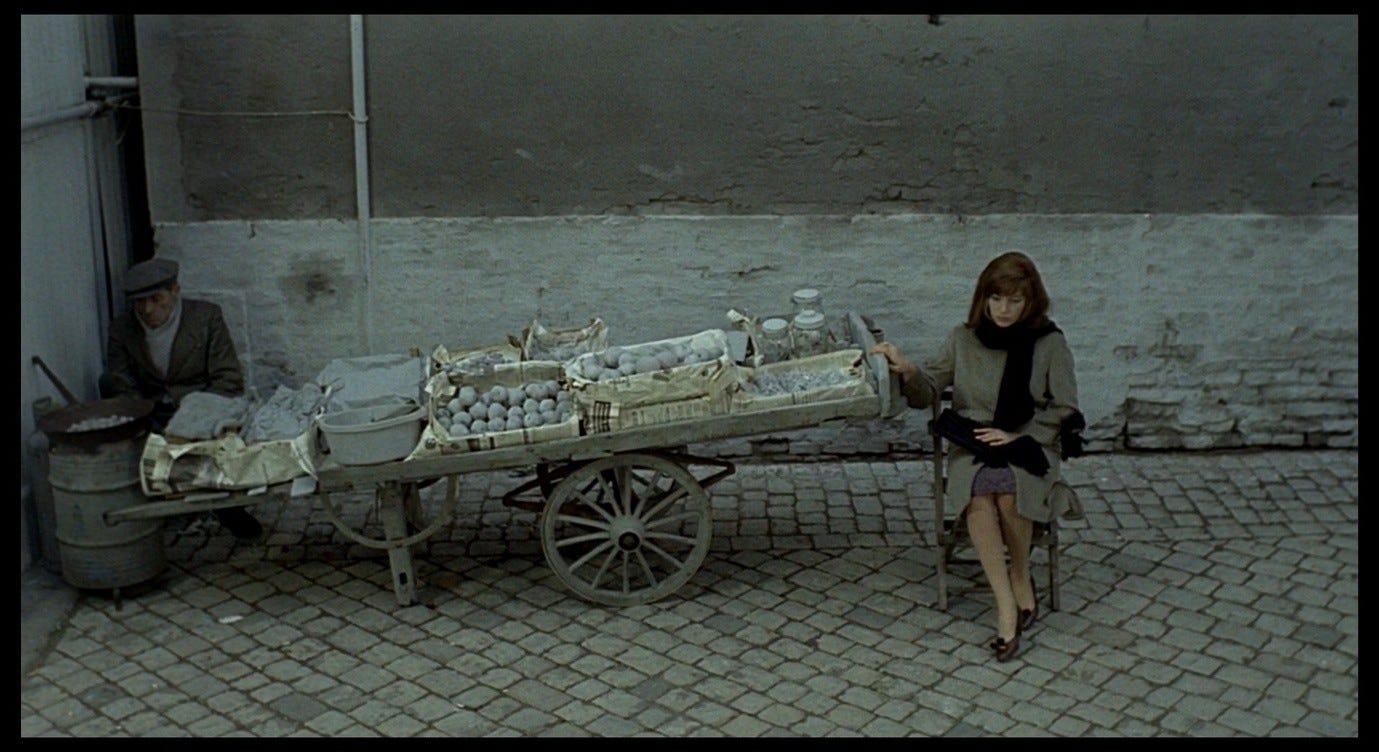

In Daughters of the Dust, we see the Peazant family gathering on an idyllic beach as they prepare to leave their island life and migrate to a city in the north.

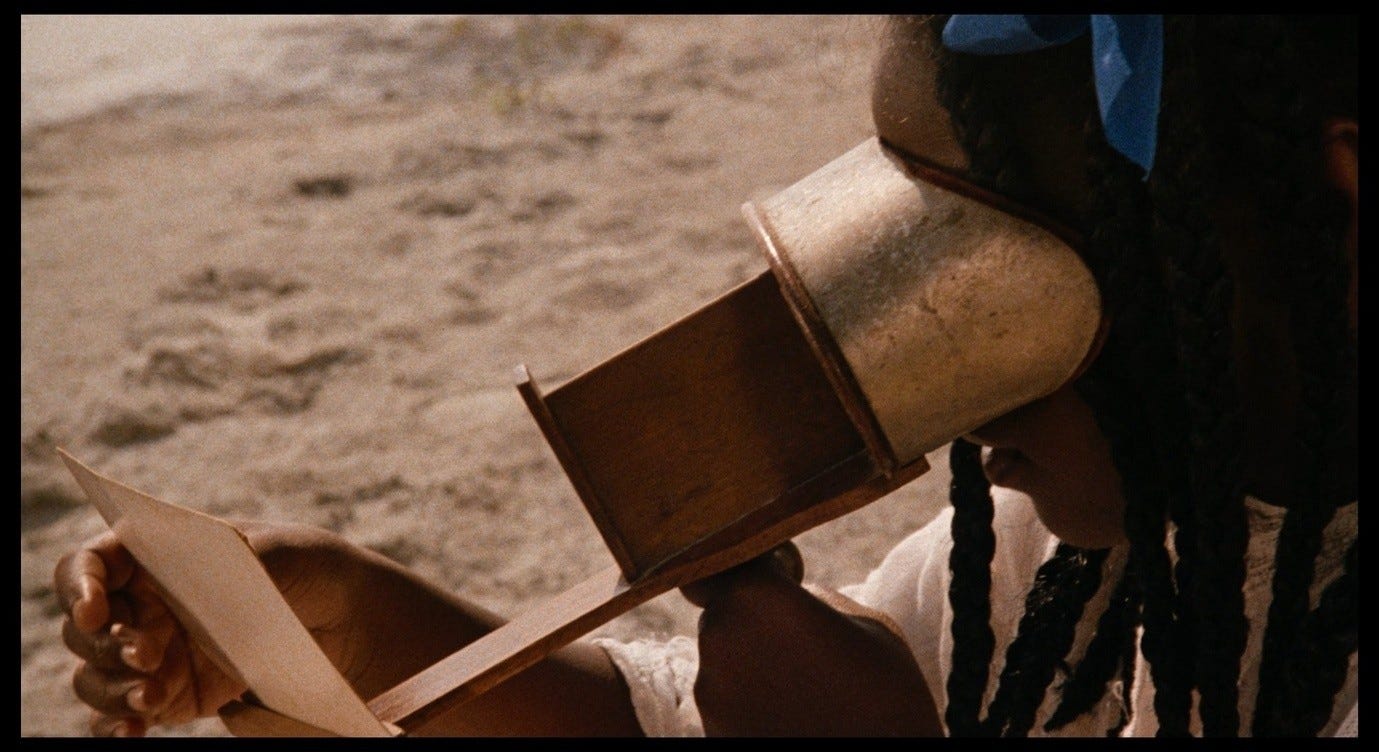

When we see photographs of the Peazants’ future home, the gaze of the Unborn Child makes these images come to life as footage from early-1900s films, appropriately given that this story takes place in 1902.

But the period-accuracy is ironic: in this film made in 1991, the ‘old world’ of Saint Helena Island looks more real and ‘present’ than the scratchy, archaic footage that ostensibly represents the future. The Unborn Child is seeing the other children’s future, not hers: her parents will stay on the island. Later, she makes herself appear in the viewfinder of Mr Snead’s camera, though she will not appear on the photograph itself; she lives on the island, and in this film, in the vivid and dynamic ‘now,’ rather than in the fossilised ‘then’ Mr Snead is recording.

Julie Dash, like Antonioni on the island of Budelli, filmed on location without artificial lighting (only reflectors). In Dash’s film, the drama centres on the same dynamic we saw in Hermann Broch’s novels: what he framed as the relationship between ‘no longer’ and ‘not yet,’ or as ‘not quite here but yet at hand’ (see Part 31), Dash frames as the relationship between the ‘last of the old’ and the ‘first of the new.’ Something will be lost in the family’s move to the north – and some people will be left behind – but something else will be gained. However, what emerges most strongly, in the course of the film, is not loss or gain but continuity. The old ways will survive both on Saint Helena Island and in the bustling modern city. We see recurring images of the Unborn Child, who narrates the film, running along the beach: she is telling (and, as in Red Desert, showing) a story about this liminal space where past, present, and future coexist harmoniously.

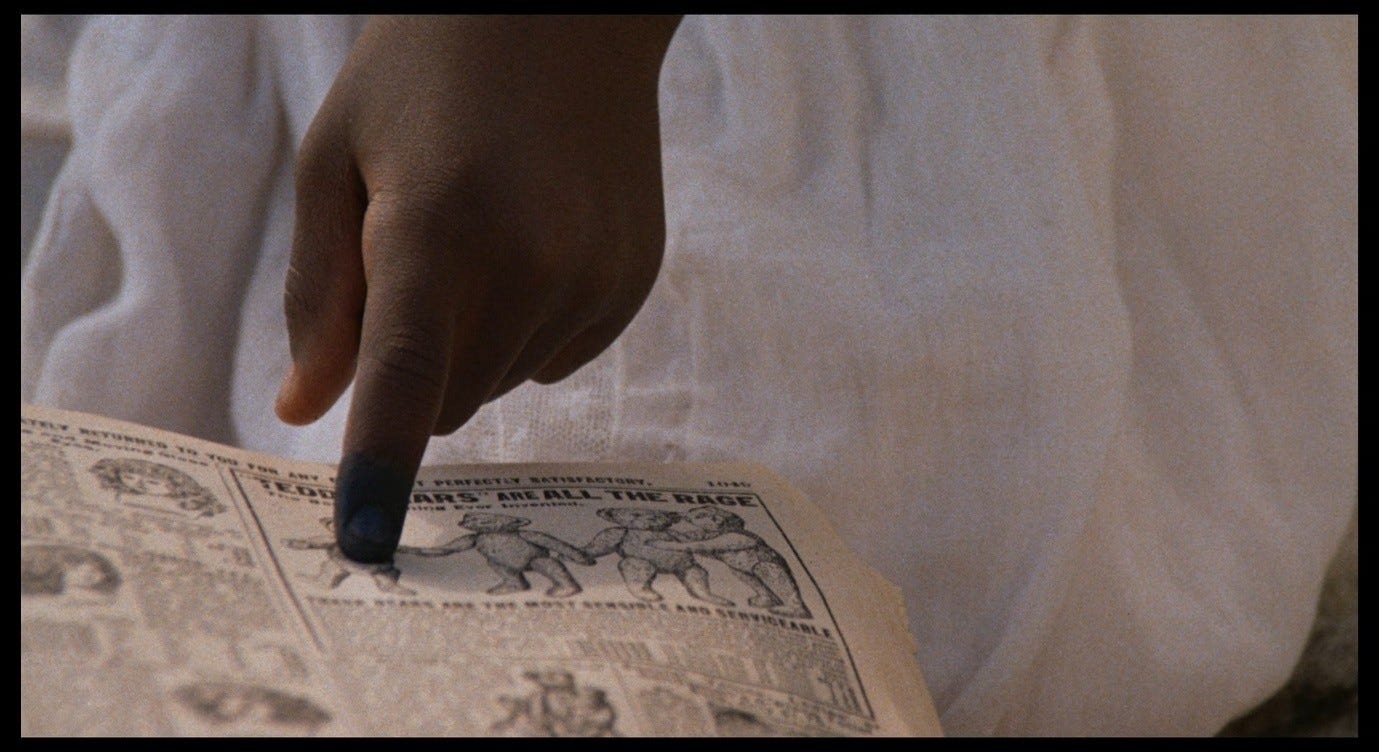

The film’s title refers to the ‘dust’ of the past – the family’s African roots, which have in a sense decayed and been reduced to dust – but reclaims this as a generative, endlessly fertile dust that clings to each successive generation of daughters. The Unborn Child witnesses her enslaved ancestors staining their hands with indigo dye, and her finger carries this stain as she points out the teddy bear she wants in a newspaper advert (teddy bears were invented in 1902). The blue ribbon in her hair also alludes to her ancestral legacy.

These images of an island paradise are part of a story, but they are not a fantasy of how things might be, or of how the Unborn Child wants things to be. They are, in fact, more real than the barely-surviving filmic representation of the once-but-no-longer-modern city. This beach, and the child-spirit who inhabits it, embody an indomitable force that transcends the vicissitudes of ‘development’ and ‘progress.’

Dash’s film provides a useful point of contrast with Red Desert in the present context. The fantasy-cove sequence, said Antonioni,

in which each element – and first of all, color – tells a fragment of the human experience, shows reality as Giuliana wishes it were – that is, different from the world that appears to her as transformed, alienated.8

From Giuliana’s perspective, it is as though reality had taken on the qualities of that early film footage that represented the ‘transformed, alienated’ place to which the Peazants were travelling.

The artifice of movie-reality has evolved and consumed Giuliana’s world, and for her the naturally-lit island is not even a memory – not even the persistent ‘dust’ of a past that can never be fully left behind – but a fantasy. The irony in Daughters of the Dust, where the modern appears archaic, is a reversal of the irony in Red Desert, where unadulterated reality appears fantastical.

For Antonioni, the lingering remnants of the past are not associated with an ancestral heritage that needs to be preserved, but with the vieilles choses that plague Giuliana: old assumptions and conventions lurking behind every relationship, shaping its course in ways that have an annihilating effect on the individual (see Parts 9 and 16). Hermann Broch traces a narrative in which old values disintegrate to the point of absolute zero (‘no longer’) and for a time nothing replaces them (‘not yet’), but in which a redemptive future can be glimpsed looming over the horizon (‘not quite here but yet at hand’). Julie Dash dramatises the process whereby the ‘last of the old’ watch the ‘first of the new’ transposing themselves into a different world, but in such a way that these two groups blur together. Their island paradise remains inviolable, a plane of reality that will be as present and tangible for those who leave it as for those who remain.

Antonioni cannot tell either of these stories. In Red Desert, the old values are paradoxically ‘no longer but yet at hand,’ while the ‘first of the new’ seem terrifyingly distinct from the ‘last of the old,’ like robots or ultracorpi who have replaced their inferior predecessors (see Part 11). We see through the eyes of one of these outdated creatures, sharing her painful awareness that the Edenic fantasy is a mark of her own obsolescence; it contains the seeds of its own disintegration. There is no daughter of the dust (or of the pink sand) here, only the son of a robot: Valerio, eyeing his mother with a critical gaze that is light-years away from the hope-instilling look the Unborn Child casts on her soon-to-be parents.

Speaking of paradise, here again is the grown-up Ana’s monologue from Cría Cuervos:

I can’t understand people who say that childhood is the happiest time of one’s life. It certainly wasn’t for me. Maybe that’s why I don’t believe in a childlike paradise or that children are innocent or good by nature. I remember my childhood as an interminably long and sad time, filled with fear. Fear of the unknown. There are things I can’t forget. It’s unbelievable how powerful memories can be.

This has a bearing on Marcus’s earlier comment about the girl in Giuliana’s story not having ‘suffered the fall into experience that will irrevocably exile her from the earthly paradise of her island retreat.’9 I think Antonioni, like Broch, sees childhood as precisely the time when we do suffer that fall, when we discover our fear of the unknown and experience traumas that can neither be processed nor forgotten. Giuliana, like Ana but in an allegorical mode, is recounting her moment of traumatic discovery: not a loss of innocence but a revelation that there is no innocence, that the soothing bedtime story of a child’s paradise is just a well-disguised nightmare full of unbelievably powerful yet unidentifiable monsters.

Sławomir Masłoń offers a differently-slanted critical view of the paradisal framing of this sequence:

[W]hat we see as the island fantasy is the ‘hyperreal’ nature known from tourist brochures – an idealized holiday destination in which nature is exclusively ‘nice’ […] and where one does not have to go to school or work. In other words, this happy image of balanced enjoyment is simply a consumer product of an industry – the Italian (or, in fact, international) tourist industry. […] [I]sn’t the Technicolor ‘cuteness’ of the island images, its tourist brochure quality, another kind of filth that stains the paradise?10

This recalls the tourist-brochure imagery in Ugo’s fishing cabin, which invoked exoticised, colonialist conceptions of Africa (see Part 21).

Indeed, Antonioni spoke of the challenges of filming on Budelli:

It took 15 days because the place was so euphoric, so reinvigorating, that no one could get any work done. I was swimming all the time.11

Something of this holiday spirit has crept into the finished sequence, which has an undertone of ‘wish you were here’ frivolity that Masłoń incisively draws out. Although Antonioni described Giuliana as telling this story ‘with great simplicity and purity of heart,’12 we see that simplicity and purity slipping away as the story goes on. Just as Ana in Cría Cuervos and Edmund in Germany Year Zero could not fully protect themselves from fascism and the other adult corruptions surrounding them, so it is impossible to live in Giuliana’s world and tell a simple, pure story of an all-natural paradise, untainted by commerce and industry (Elena Past’s comments about the Budelli island, quoted in Part 2, are also relevant here). The impossibility of Giuliana’s story is made manifest in the two other-worldly phenomena that simultaneously constitute its plot and dismantle it from within.

Next: Part 35, The ship and the song.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Benayoun, Robert, ‘Le désert rouge’, Positif 66 (1965), pp. 43-59; p. 58 (my translation)

Benayoun, Robert, ‘Le désert rouge’, Positif 66 (1965), pp. 43-59; p. 58 (my translation)

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), p. 206

The ship in Giuliana’s story is similar to the Leader, built in 1892, or to the Tres Hombres, a traditional-style sailing boat built in 2009 to promote sustainable shipping.

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp. 109-110

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), p. 202

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 104

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; p. 285

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), p. 202

Masłoń, Sławomir, Secret Violences: The Political Cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960-75 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023), pp. 100, 106-107

Benayoun, Robert, ‘Le désert rouge’, Positif 66 (1965), pp. 43-59; p. 58 (my translation)

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; p. 285