Everything That Happens in Red Desert (21)

Corrado's philosophy

At several moments throughout the chaotic daytrip, Corrado shares his personal, political, and professional reflections, sometimes in conversation with Giuliana, sometimes unprompted. These seemingly inconsequential moments contribute to the development of the connections and contrasts between Corrado and Giuliana, as well as adding some important dimensions to the dominant motif of this sequence – escape.

Corrado makes a confession to Giuliana and Ugo as they inspect the latter’s neglected fishing hut: ‘Sometimes it seems to me I don’t have the right [diritto] to be where I am. Perhaps that’s why I always want to keep moving.’ As he says this, Corrado is looking at a picture on the opposite wall of the hut, which is described as follows in the screenplay:

One wall is still covered, almost entirely, by a tourism poster depicting zebras in a tropical clearing: it gives the impression of being in a different place, a different climate [in un altro luogo, in un altro clima].1

Ugo has apparently decorated his hut to give it an exotic atmosphere, enabling it to serve its purpose as a place of escape. Industrial Ravenna is overrun with humans and human-made products, so the picture shows a purely natural setting inhabited only by animals. This image of a distant place makes Corrado think of his compulsive need to move from one place to another, but rather than framing this in terms of escape from oppressive limitations or an over-familiar setting, he talks about not having the ‘right’ to be where he is. Given that he has just been lamenting over the polluted lakes (‘What a shame’), and given that Ugo has just admitted he has not visited this hut in two years, Corrado may be offering a critique of his and Ugo’s (and other men of industry’s) impact on their surroundings. Perhaps these men should not be here, ruining and neglecting this land, making it impossible to go fishing in, never even finding the time to fish in it. But Corrado’s comment also refers back to his conversation with Ugo during the factory tour, when he said that he had changed his line of work in order to take up his father’s legacy: in one way or another, Corrado feels like he is doing the wrong job in the wrong place.

Corrado leans in the doorway of Ugo’s shack, a liminal position that is appropriate for a speech about never wanting to remain in one place for long. He occupies a similar position later, in Max’s shack, when he responds to Max’s advice about ‘not running after deals.’ Leaning against the partition that gives access to the cloakroom, Corrado gives another self-explanatory speech:

But I don’t go running after anything. I travel because I like it, because I think it’s right [giusto], at a certain moment, also to change one’s life, one’s activities. Travelling makes sense if one changes – how can I say it – one’s historical context [ambiente storico], otherwise what’s the point?

Max, rubbing the back of his head, replies ‘I don’t really believe that.’ Antonioni himself would echo some of Corrado’s philosophy in a 1975 interview, responding to the interviewer’s suggestion that there is an ‘African aura’ in many of his films:

I know Africa very well. I was there as a reporter, even when World War II broke out. I went back later and visited the country extensively for long periods. More than the desert in and of itself, I always felt the need to live in a different historical context, in a nonhistorical world, or in a historical context that is not conscious of its own historicity.2

There is obviously something problematic in Antonioni’s characterisation of Africa as ‘nonhistorical’ or ‘not conscious of its own historicity,’ which belies his claim to ‘know Africa very well.’ ‘I’ve been with them since the war started, and I’m starting to know them,’ says the French officer in Ousmane Sembène’s Emitaï, explaining (to his subordinate) how best to manipulate the Diola villagers, who are being forcibly ‘recruited’ to fight for the Vichy government in World War II.

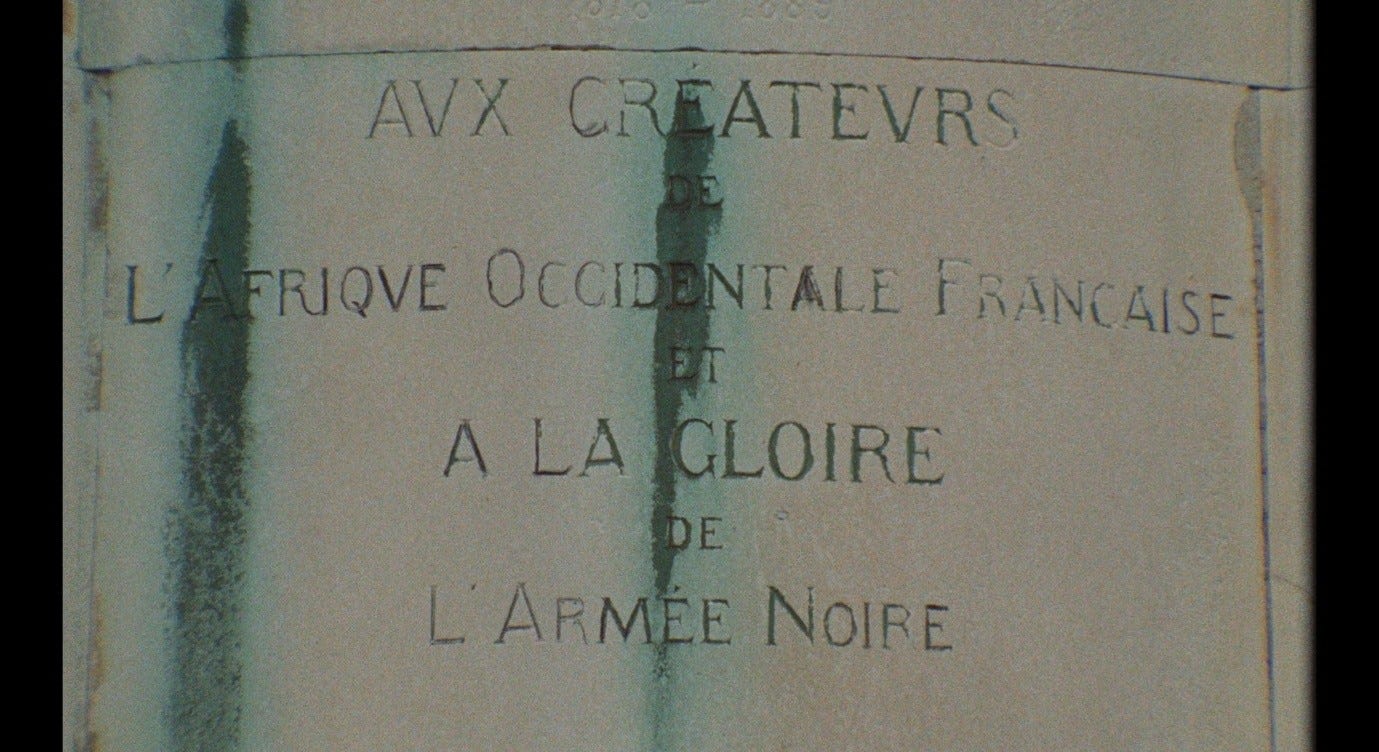

Sembène, filming in 1971, shows the now-weathered statues commemorating these soldiers’ sacrifice, one of which bears the inscription: ‘To the creators of French West Africa, and to the glory of the Black Army.’

The marching soldiers sing, ‘Maréchal, nous voilà!’ as though they have sprung into existence purely in order to join in this war. They are treated as a people with no history, no past, only a present: here they are, now, voilà, to be exploited. Ironically, it is France whose past and present become truly unstable as the film goes on, when posters of de Gaulle are papered over those of Pétain, with no discernible change in circumstances for the Diola people.

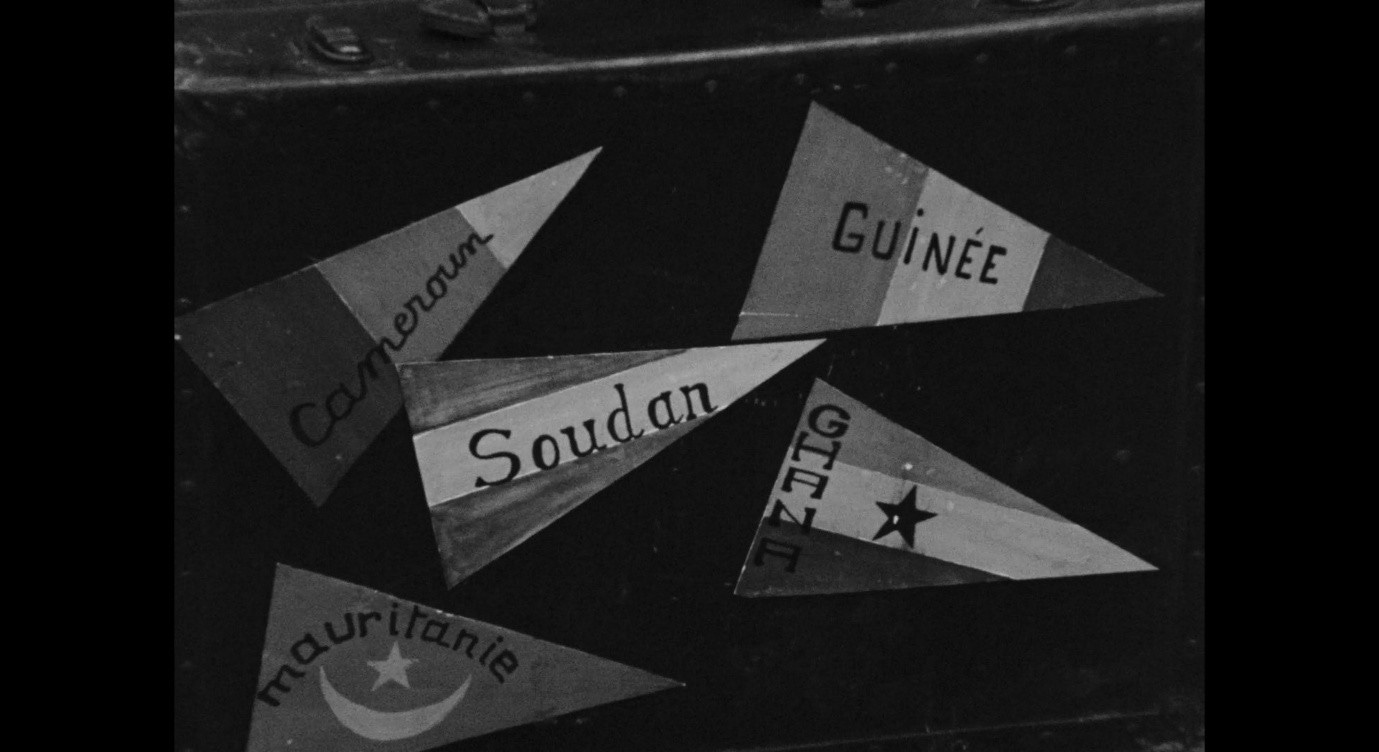

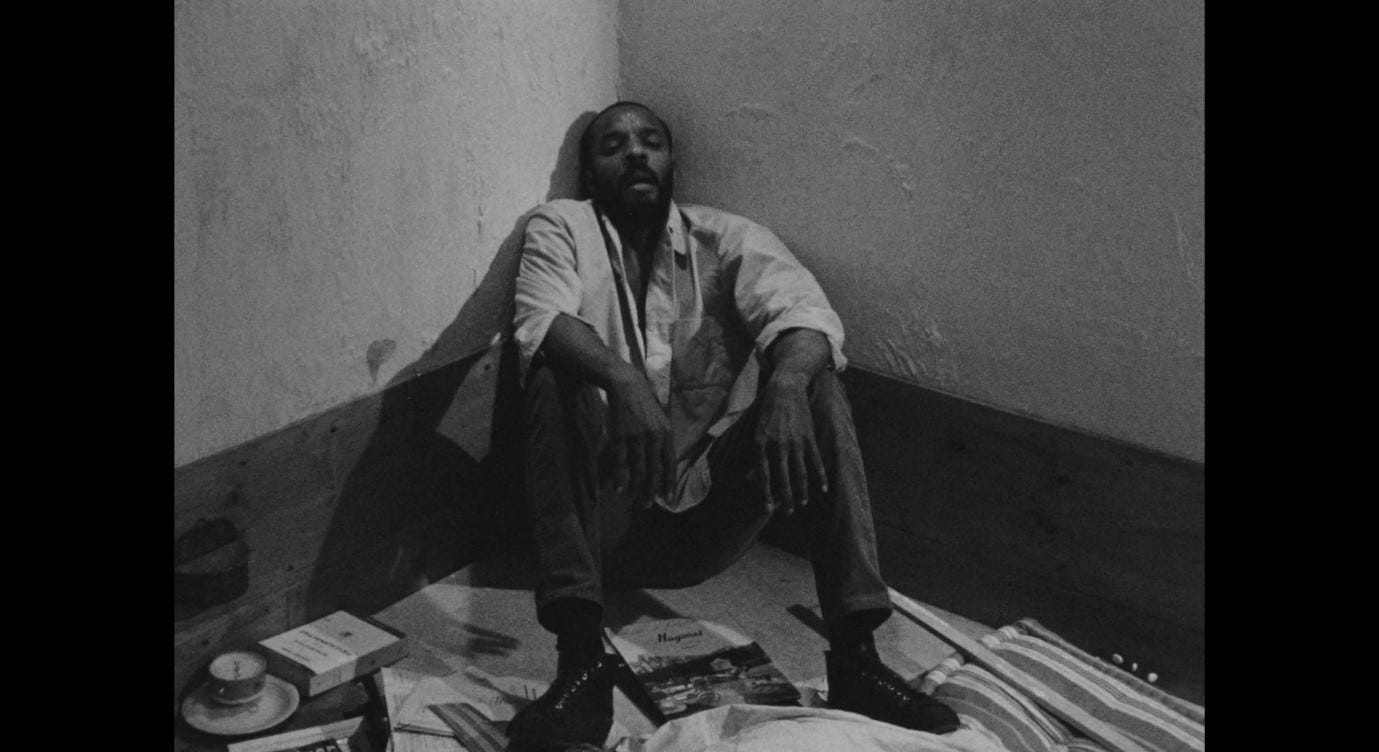

In Med Hondo’s Soleil Ô, an unnamed protagonist emigrates from an unnamed African country (French-language names of several are plastered over his suitcase, as though he is returning from a holiday) to make a new life in France. ‘Je viens chez toi,’ he says hopefully as he arrives, ‘je viens chez moi.’

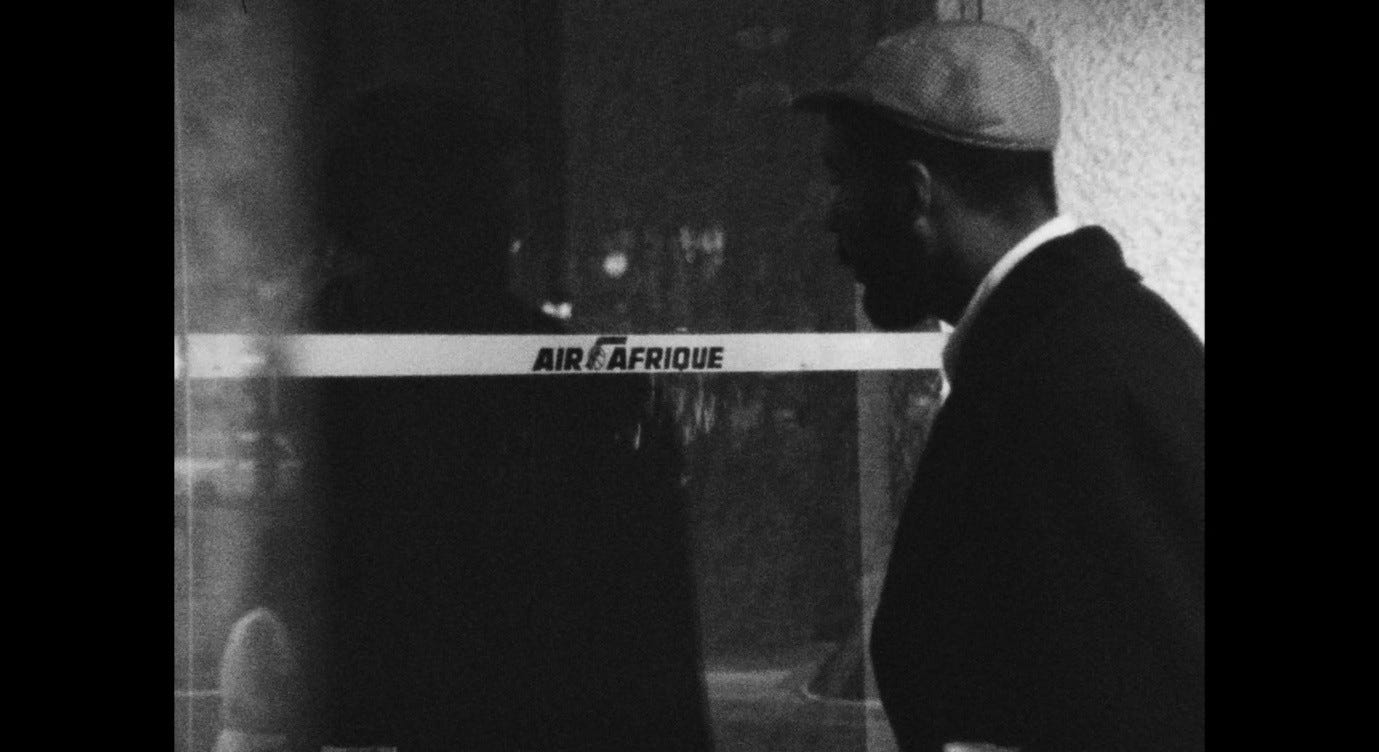

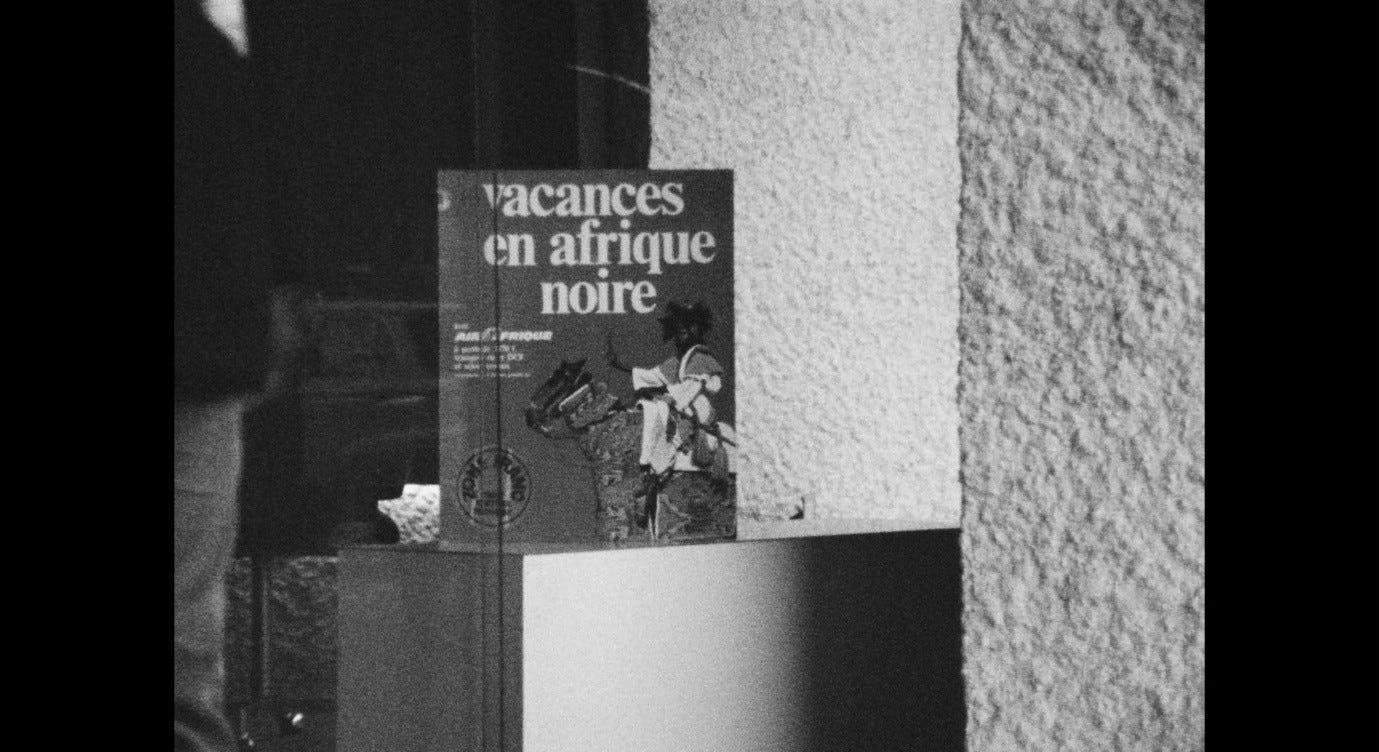

This place is ‘elsewhere,’ someone else’s home, but now it will be his home. Living in Paris, however, he begins to suffer an identity crisis as he grapples with the systemic effects of colonialism. He eagerly goes into a travel agency looking for work, after seeing an Air Afrique poster in the window. He comes out looking disappointed, and notices another poster advertising ‘Holidays in Black Africa’, an echo of the picture hung up in Ugo’s shack.

France, having colonised Africa, now markets it as a distant, exotic holiday park you can escape to, while denying all but the most menial jobs to African immigrants. The narrator of Soleil Ô becomes increasingly enraged at the complacency with which this racist status quo is maintained: ‘With a serene spirit, you sleep peacefully,’ he growls at the French bourgeoisie. ‘A pleasant feeling of having a clear conscience envelops you.’ He could be addressing Corrado, whose main priority in life (as we will see later) is to maintain a clear conscience.

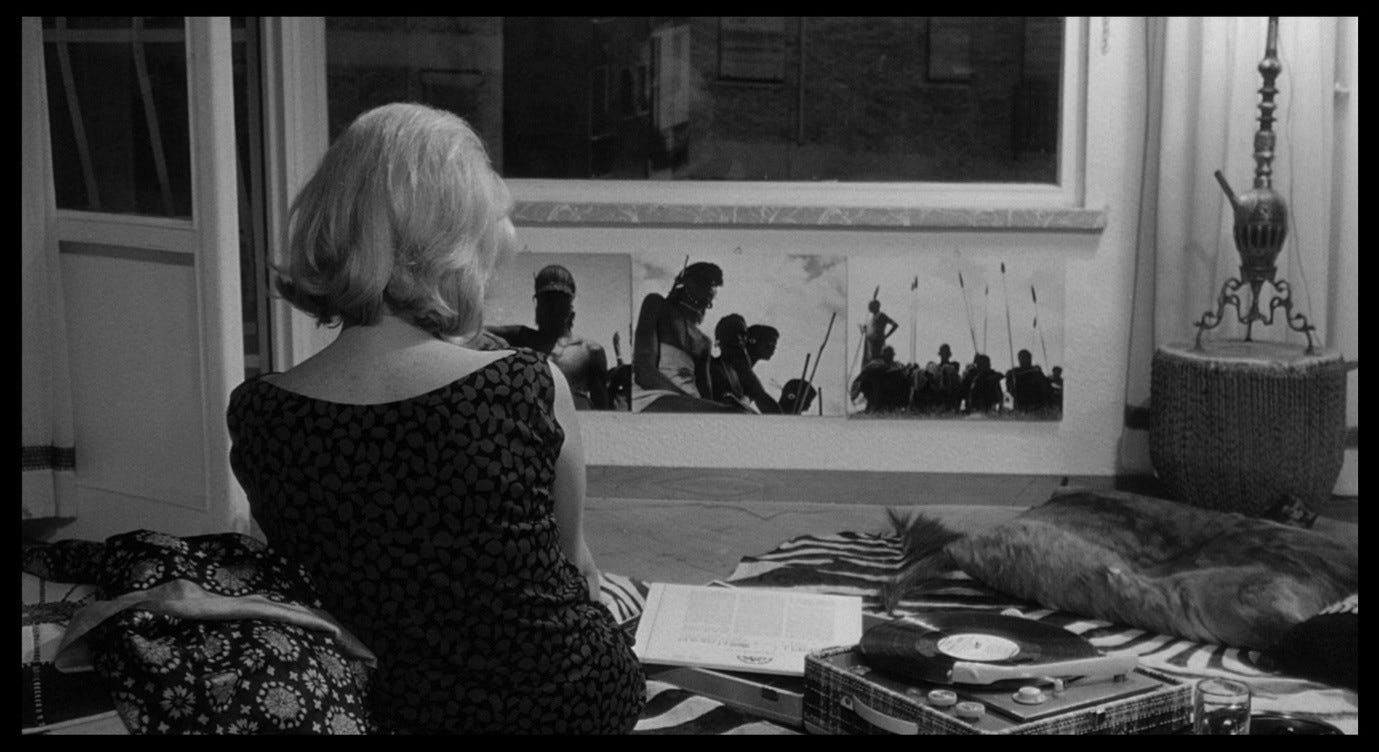

Antonioni’s conception of Africa, and the (partially self-aware) sense of ignorance that comes with it, are manifested in several of his films. The most infamous example is Vittoria’s blackface dance in L’eclisse (not directly pictured below), which for her clearly represents the kind of escape Corrado is seeking: a different context, less modern, less burdened by millennia of ‘history’ than the Rome in which Vittoria is struggling to carve out a life for herself. Her performance is inspired by her new friend Marta’s tales of growing up in Kenya, but Marta suddenly seems offended and the dance comes to an abrupt halt.

This is another Antonioni moment of joyous excitement cut short by shame and embarrassment, like the one in Max’s shack. Marta’s outrage is not prompted by the racism of Vittoria’s behaviour (or by the other friend, Anita’s, enjoyment of the blackface dance), but by its frivolity. According to Marta, the black population of Kenya are uncivilised ‘monkeys’ who pose a threat to her and her family. Antonioni (or rather, his film) does not overtly critique or endorse these views, but they have the effect of cooling Vittoria’s naively colonialist African fantasy. To some extent, Vittoria is the butt of this scene’s wry humour: it is as if Antonioni were reflecting on his own desire to escape into an ahistorical Africa, and seeing that desire rudely confronted with the traumatic history (and traumatic present) of a real Africa that he does not understand.

Angelo Restivo analyses this scene from L’eclisse in a way that will resonate with later discussions about ‘wrested objects’ in Red Desert:

With a mise-en-scène abounding in indexical signs of ‘Africa,’ the sequence can be understood as a continuation of Antonioni’s critique of the ontological grounding of such signs: once wrested from the life-world in which they are embedded, these artifacts and photographic views cannot be reassembled in any meaningful way. They exist only as the ‘loot’ of an acquisitive, colonialist gaze. But Vittoria’s performance reveals that she is engaged in a kind of mimicry, an attempt to escape the terrors of the gaze by refashioning the self in such a way that image and ground become indistinct. She cannot succeed at this point, because the space of the apartment is not a world but a museum. But this absorption of figure into ground […] is also where L’eclisse is heading.3

That ‘acquisitive, colonialist gaze’ – plundering the loot of the world but struggling to reassemble its meanings, lapsing into a state of ennui or sheer boredom – is very much in evidence in and around the Red Desert swamp. Where L’eclisse shows a museum-like apartment full of artefacts from a colonised-and-resented culture, Red Desert shows neglected, disintegrating fishing huts, pathetically decked out with images of unspoilt distant lands and surrounded by lakes whose inhabitants are no longer safe to eat. The idea that Vittoria lives in ‘terror of the gaze’ and that she tries to escape this through mimicry resonates with Corrado’s guilt over the effects of industry and his sense that he has no right to be here – his sense, that is, of being subject to some unseen figure’s scrutiny and judgement, prompting him to want to change his self, his activities, his ‘context’ in every respect. Restivo suggests that the ending of L’eclisse accomplishes that ‘absorption of figure into ground,’ that escape from the gaze that Vittoria longs for. Red Desert picks up on this idea, especially through Giuliana’s comments about absorption and dissolution (as we will see again in Part 22), but for now it is important to note that Corrado too experiences something of this anxiety. Using Restivo’s terms (figure/ground) we might re-frame the fear of history as a fear of depth, of three-dimensionality, from which the collapsing effects of Red Desert’s telephoto lens offer a kind of escape that is itself somewhat nightmarish.

Matilde Nardelli unpacks the nature of the ennui and boredom experienced by the characters in L’eclisse:

What, in their white, Eurocentric positioning, Vittoria and Anita seem to value in Marta’s clichéd, holiday-brochure kind of imagery is precisely the kind of spatial and temporal ambiguities that allow them to receive and construe these images as elsewheres and outsides of (Western) modernity. Yet of course […] the very abundance of such imagery is inevitably leading to the elimination of the category of the ‘elsewhere’, fast subsuming it under that of the ‘familiar’ instead. […] Vittoria enacts the colonialist, ethno-touristic mode of representation through which Maasai women have been made ‘available’ to a Western audience – an often de-historicised ‘other’ whose difference is at the same time constructed, displayed and erased, through the very anonymity, frontality and repetitiousness of the images, and whose ‘elsewhere’ has nevertheless been brought ‘here’.4

In Soleil Ô, the protagonist says to himself, ‘Here or elsewhere, I am at home [Ici ou ailleurs, je suis chez moi].’ But this idealistic sentiment is uttered as a protest against his immediate circumstances: a mechanic (whose face is darkened by motor oil) is refusing to employ him, for reasons that are unstated but painfully obvious.

This moment of deflation echoes but reverses the one in L’eclisse. Vittoria is making herself ‘at home’ in her new friend’s apartment, but delighting in her capacity to transport herself ‘elsewhere.’ The hero of Soleil Ô finds himself both burdened with the label of ‘elsewhere’ – of the undesirable other – and helplessly trapped ‘here’ in a place that refuses to let him be ‘at home.’ Vittoria would be a villain in Hondo’s film, fetishising the immigrant’s elsewhere-ness but incorporating it into the framework of ‘here,’ then becoming disillusioned and bored with it. In the context of an Antonioni film, of course, Vittoria is presented not so much as a racist coloniser but as a tragi-comic figure engaged in a misguided and futile attempt at self-escape.

In The Passenger, David Locke interviews an African witch doctor (or at least this is what David calls him). The interviewee remains silent in the face of David’s questions about tribal customs and whether they seem ‘false’ to him since he came back from Europe. At last, the interviewee responds:

Mr. Locke, there are perfectly satisfactory answers to all your questions. But I don’t think you understand how little you can learn from them. Your questions are much more revealing about yourself than my answer would be about me. […] [He turns the camera around so the lens is pointing at Locke.] Now we can have an interview. You can ask me the same questions as before.

David laughs uncomfortably. The footage is being watched by his wife, who comments bitterly on her husband’s passive, accepting attitude towards the subjects he investigated. The camera-turning gesture forces David to reflect, not so much on the impact he might have on the culture he is documenting, but on the possibility that he may not be documenting that culture at all. Like Antonioni yearning to be ‘unconscious of history,’ David has placed himself behind the camera in an objective, journalistic stance in order to escape from something that is inescapable. Antonioni explicitly drew a connection between himself and David in another interview:

I noticed a sort of obscure intolerance, the need to escape, through the characters in the film, from the historical context in which I and they lived – that is, the urban, civil, and civilized context – to enter another environment such as the desert or the jungle, where you can at least attempt a freer, more individual lifestyle, where such freedom could be tested. The adventurous character, the reporter, changes his identity to free himself from the self who had been ignoring such a need. […] [He wants to escape] from a certain type of history. […] [I]t is from himself that the character is escaping, from his own history, not from History with a capital ‘H.’5

The camera-turning scene in The Passenger also recalls Antonioni’s comment about Zabriskie Point: ‘It is me in front of the camera saying what I feel about my America.’6 Narcissistic as this may sound, it is an important component in his appropriations of other cultures in these films. Antonioni does not literally appear in front of the camera except in Lo sguardo di Michelangelo, and even there the title displaces his identity onto another (historically distant) Michelangelo. But he is always using the profilmic space, including the sculptures of that other Michelangelo, to express something about himself. His language in the above quotation stresses uncertainty: he describes an ‘obscure intolerance,’ a need for settings where one could ‘at least attempt’ or ‘test’ other lifestyles. Ultimately, he comes back to the sense that all our feelings about History are truly feelings about our own personal history. The history-conscious self denies its own needs and thus spawns a second self, but one that cannot ever achieve an independent (de-historicised) existence.

Corrado, like Vittoria and David, embodies this desire for ever-changing contexts and holidays from the self. He contributes little to the conversation in Max’s shack, except when he chips in to share his knowledge of exotic aphrodisiacs in faraway lands.

Here and in his shop-talk, Corrado presents himself as an urbane man of the world, but it is as though he has nothing to offer and nothing to cultivate in himself other than ‘being well-travelled.’ When he tells Max that one should travel in a way that changes one’s ambiente storico, he adds, ‘otherwise what’s the point?’ As the film goes on, it becomes clear that he is plagued by this sense of pointlessness. However much he changes his context (physical or historical), the objective of these wanderings remains unclear and un-fulfilled.

Francesco Rosi, reflecting on his experience of working with Antonioni in the early 1950s, comments on his fellow director’s approach to ambiente:

Cinema then insisted on the environment [ambiente, also meaning ‘setting’, ‘location’, ‘surroundings’], as much as the choice of performers. In Antonioni, the choice of an environment was crucial also for the description of a character. […] Antonioni was trying to give a very precise image of the social dimension. In this, he was a child of neorealism; his interest in the social element to pull out of a film came from that.7

Antonioni adopts a neorealist approach but with a profound twist. Rather than seeing how a character’s material life functions within a real setting, a real setting is made into a ‘description of character,’ and the ‘social dimension’ is defined very precisely in order to explore how it shapes the inner life of that character. Karen Pinkus expands on the significances that can attach to ‘environment’ in Antonioni:

The Italian word ambiente refers simultaneously to both interior/set design and the Umwelt – what is ‘out there’ beyond the human, perhaps Nature itself in the most reified and clichéd sense. This web of meanings is especially intense in Antonioni where a film’s ambiente may refer to the locations scouted so carefully, the sets designed/altered by an architect or art director […] and the ‘natural landscape’ inhabited by his characters.8

Pinkus’s reference to the ‘reified and clichéd’ ambiente of Nature recalls the equally reified and clichéd ambiente of Africa, discussed above. The out-there-elsewhere culture – America, Africa, Nature – is portrayed by Antonioni in a very precise, deliberate way, but by the same token it has been very carefully constructed. It is a ‘web of meanings,’ and meanings – as Roland Barthes said in reference to Antonioni (see Part 16) – are not to be confused with truths. So what is Corrado’s ambiente, how is his character described through it, and what ‘web of meanings’ does it weave around him?

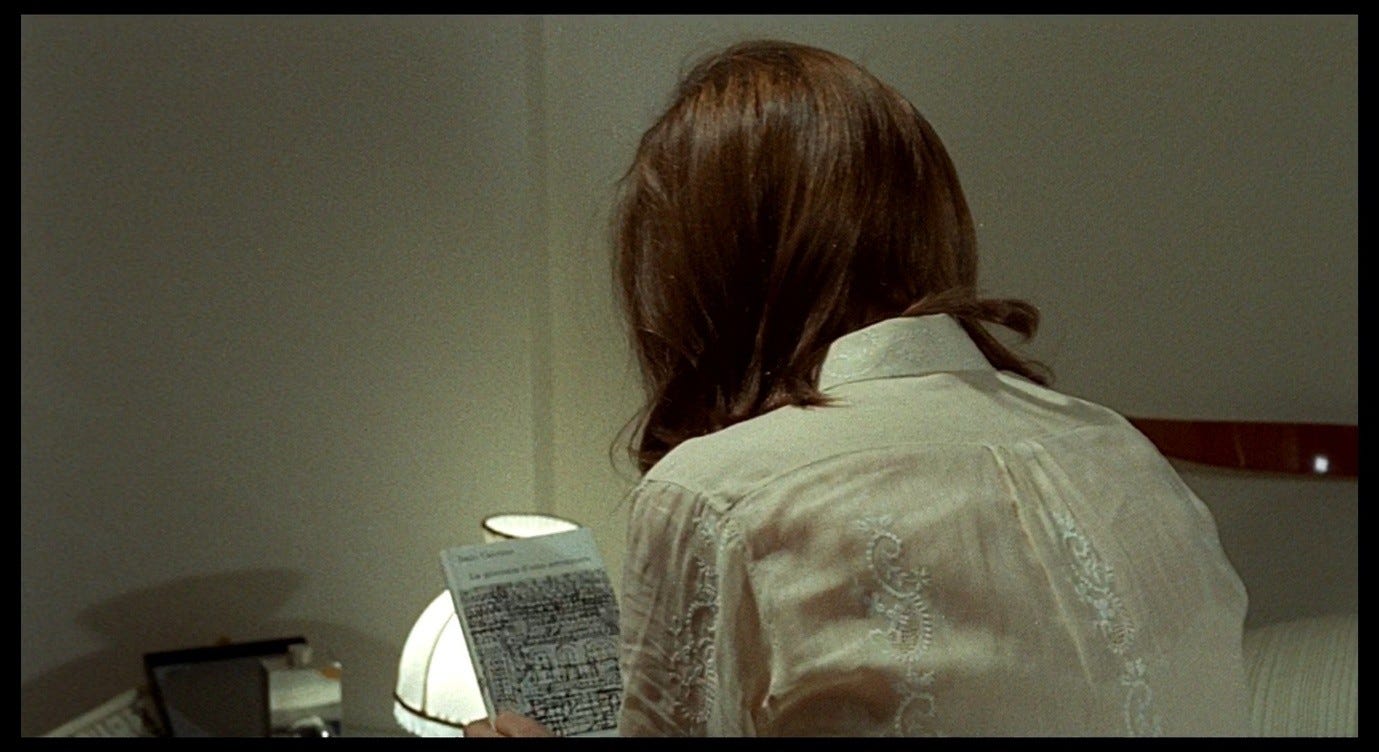

Later in Red Desert, we will see a copy of Italo Calvino’s novella, La giornata d’uno scrutatore (literally The day of a watcher, and known as The Watcher in English) on Corrado’s bedside table. Giuliana picks it up and looks at it, giving the audience a moment to register its presence.

The term scrutatore here denotes a polling clerk who helps to oversee the registering and counting of votes in a local election. The novella’s protagonist, Amerigo, undergoes a series of internal crises while ‘watching’ the election in Cottolengo, agonising over the relation between his political identity and his historical context. Why, for instance, is he a Communist rather than something else?

Asking himself this question, for Amerigo, was like asking himself what was the essence of an individual identity (if such a thing ever existed...), beyond the external conditions that determined it. To weld in him – and in so many like him – those various metals was ‘the task of History,’ he thought.9

This may help to explain Corrado’s desire for change: if the self and its beliefs are forged by one’s historical context, changing that context would mean engaging with something radically unfamiliar and would therefore present new opportunities. This is Corrado’s questing, exploratory approach to his work, in contrast to Max’s conservatism (he stays where he is and lets the opportunities come to him). However, Corrado also equates the change of historical context to a change in one’s ‘life’ and ‘activities,’ as though (like Amerigo) he thinks that the self and its behaviour – dependent as they are on context – would transform completely in a new place. In this sense, he again resembles David Locke, not simply challenging his (stable, consistent) self through exposure to a foreign culture, but exchanging his (malleable, contingent) self for another.

In the same passage in The Watcher, Amerigo’s hand-wringing extends to his whole attitude to life and politics. After performing a conciliatory role in a political dispute, he is

pleased with himself, with his calm, his self-control. Perhaps this was what he wanted to be his behaviour’s constant norm, in politics as in everything else: mistrust of enthusiasm, synonym of naïveté, as of factional rancour, synonym of insecurity, weakness. This attitude of his corresponded to a habitual tactic of his party, which he had promptly assimilated, as psychological armour, to dominate alien, hostile situations. However, as he thought about it, wasn’t this desire of his to wait, not to intervene [...] dictated by a feeling of futility, of renunciation, by a basic laziness? [...] [H]e was inspired not so much by a spirit of tolerance and of solidarity with his neighbour as a need to feel superior, capable of thinking all that was thinkable, even the adversary’s thoughts, and capable of reaching a synthesis, of perceiving everywhere the patterns of History, according to the prerogative of the true, liberal spirt.10

With this passage in mind, consider how Corrado responds to Giuliana, early on in the daytrip sequence, when she asks him whether he is left- or right-wing:

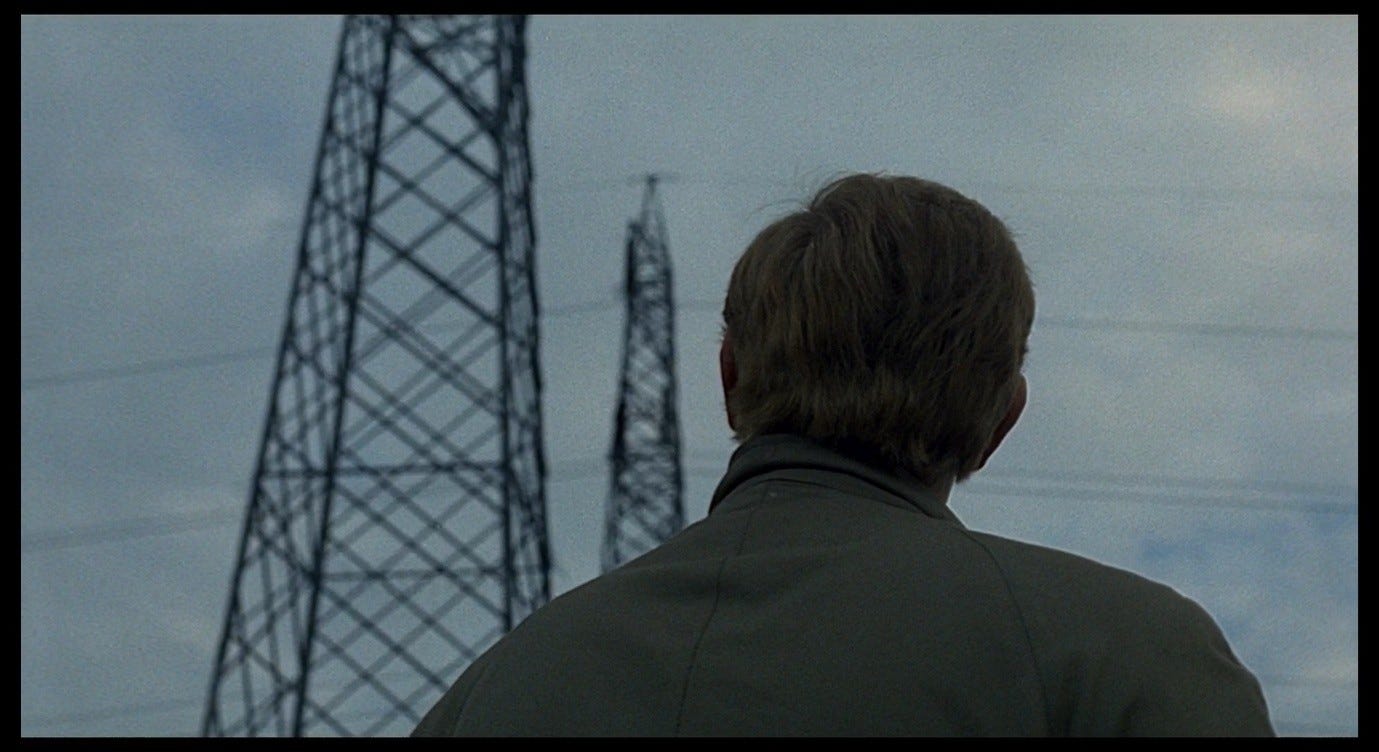

It’s like asking: what do you believe in? These are big words, Giuliana, which require precise responses. In the end, one doesn’t really know what one believes in. One believes in humanity, in a certain sense. A little less in justice [giustizia]. A little more in progress [progresso]. One believes in socialism, perhaps. The important thing is to act in the manner that one considers just [giusto], just for oneself and for others, that is, to have a peaceful conscience. Mine is tranquil. Is that what you wanted to know?

Here, as usual, Corrado speaks in a highly performative way. He begins by asserting that one must answer such weighty questions with precision, and indeed his answers sound like they were composed and rehearsed in advance. His movements seem choreographed: he pauses for rhetorical effect at all the right moments, modulating his facial expressions like a practised orator. As he refers to ‘progress,’ he looks up at the pylon towering over them, casually making use of his surroundings to illustrate his point.

Corrado speaks while strolling along the bank of a polluted lake, and the camera occasionally cuts to a reverse-shot of Giuliana spectating his performance. She responds to his composure and self-control with the same mildly anxious look she gave him when they met in her shop, but now this look transitions into amusement.

When Corrado stops talking, Giuliana responds with gentle mockery, ‘You’ve put together a pretty bunch of words,’ taking off her scarf and holding it up.

As when he gestured towards the pylon, she is using an object to illustrate a point: the scarf is analogous to Corrado’s speech, an artificial piece of fabric woven together for the sake of concealment and protection. Her removal of the scarf exposes her to the cold weather, hints at her willingness to reveal herself to him, and encourages him to reciprocate.

There is a significant relationship, here, between the characters’ speech and their ambiente, as Angela Dalle Vacche argues:

Outside the factory, at the beginning of the film, even though the noise of the machinery is deafening, Ugo and Corrado continue talking. All their verbal activity, however, has a touch of impotence, for it does not propel the narrative forward in any way. By contrast, even if Giuliana’s remarks about the ship with the yellow flag are not taken seriously by her husband, she quickly characterizes Corrado’s eloquence about politics and personal morality by pointing out to him that he speaks in an empty language. In other words, although language belongs more to men than to women, Ugo and Corrado are unable to use it to say something interesting or new.11

This ‘impotence’ and ‘emptiness,’ this impression of meaningless speech amidst deafening noise, suggests a kind of passivity in these seemingly active male characters. It is the same passivity inscribed in the title of The Passenger (he is always going somewhere, but is never the driver) and in the alternate Italian title, Professione: Reporter (he is always speaking, but only in echoes or ‘reports’ of others). Also instructive here are the points of contact between Corrado’s speech about politics and Amerigo’s (fundamentally passive) role in The Watcher. When Corrado uses the ‘it’s like asking’ formulation, this resembles Amerigo’s meditation on identity (‘asking himself this question was like asking himself…’). Corrado’s impersonal evasiveness recalls the polling clerk’s studiedly withdrawn demeanour (‘his calm, his self-control, psychological armour, a basic laziness’). Like Amerigo, Corrado proves himself ‘capable of thinking all that was thinkable,’ and as Giuliana hints, he too is using this ‘liberal’ mindset as a kind of protective armour, a way of not engaging with the world around him. Being capable of thinking anything might entail believing nothing, just as (for David Locke) being capable of being anyone might entail being no one. The idea that Corrado’s speech is merely a ‘pretty bunch of words’ with no substance behind it overlaps with Amerigo’s sense that his so-called identity might not have any ‘essence,’ that it has simply been ‘welded’ together by external conditions.

Corrado’s reflections on justice and conscience are comparable to another passage in The Watcher, in which Amerigo looks at the aged, debilitated voters of Cottolengo (a religious hospital) and reflects on their habit of voting only from pious motives, as these are the only motives that make sense in the context of their lives.

So were progress [progresso], liberty, justice [giustizia] then only ideas of the healthy (or of those who could, in other circumstances, be healthy), ideas of a privileged class, not universal ideas?12

Amerigo then wonders what he and ‘the healthy’ have that these voters do not:

[N]ot much, compared to the many things that neither we nor they manage to do or know...not much, compared to our presumption that we can construct our history.13

But then, reassuring himself that progress is possible even in Cottolengo, Amerigo attempts a more hopeful attitude:

‘A man who behaves well in history [agisce bene nella storia],’ he tried to conclude, ‘even if the world is Cottolengo, is right [giusto].’ And he added hastily: ‘Naturally, to be right is not enough [Certo, essere nel giusto è troppo poco].’14

Like Amerigo, Corrado sifts through his ideals – humanity, justice, progress, socialism – questioning each one’s validity. One believes in humanity, but ‘humanity’ is a vague concept, so one must specify the ‘certain sense’ of humanity one believes in. Corrado says ‘in a certain sense’ in a moderating tone, as though reining in the idealism of ‘believing in humanity.’ Idealism takes another hit in his next phrase, ‘a little less in justice.’ Perhaps Corrado’s thought process is similar to Amerigo’s on the subject of essere nel giusto. Arguably, ‘being just’ carries little weight in a society that is undergoing drastic change and whose values are constantly being re-evaluated. Even the concept of ‘humanity’ can be understood in multiple senses. So it seems appropriate to then say, as Corrado does, that one believes ‘a little more in progress,’ and in a progressive ideology like socialism…but only ‘perhaps’ because scepticism is part of the modern, progressive mindset as well. The towering pylon Corrado looks up at when he refers to ‘progress’ is an undeniable fact one can put one’s faith in: for better or worse, progress happens and new things are built. The individual’s experience of life is another undeniable fact, and this is where Corrado finally anchors his morality.

Corrado sounds as though he is trying to compose a moral aphorism that will serve as a definitive credo, and then another aphorism that will give him some critical distance from that credo. The aphorisms are framed as impersonal, abstract statements about what people do or should do. Corrado’s speech begins with the disclaimer that ‘one doesn’t know what one believes.’ This is presented as a universal truth (implying that anyone who thinks they know what they believe must be deluded) rather than a personal confession (‘I don’t know what I believe’). It ends by retreating from ideology and adherence to the left or the right, into an individualistic morality that prioritises acting in a way that one considers just, for oneself and for others, so that one’s conscience is at peace. Only at that point does Corrado finally refer to himself when he declares that his own conscience is at peace.

This comment not only recalls Calvino’s novella, it also anticipates Antonioni’s response (in a 1979 interview) when asked about the artist’s obligations to political, social, and moral ideas:

What’s important is to be at peace with your conscience. That’s all. I do not know if this means reasoning in ethical or political terms. I am sure that politicians rarely reason in this way.15

The mild cynicism of this last comment is key to understanding Amerigo’s, Corrado’s, and Antonioni’s focus on personal conscience. The world we live in (Antonioni seems to say) is governed by people who are not interested in ethics or even politics, but only in themselves, and specifically in their own popularity and material gain. There is little stability to be found in the realm of politics, or in ethical principles, or in history, so the only viable way to live is to pursue an internal sense of ‘being just.’

Corrado appears complacent when he smiles and declares that his own conscience is at peace. However, when he then asks Giuliana, ‘Is that what you wanted to know?’, this question frames the preceding speech as a performance for her benefit. Her joking response about his ‘pretty bunch of words’ reinforces this impression, undermining the integrity he seems to have claimed for himself. In the context of his remarks (throughout the rest of this sequence) about his perpetual need for travel and change, Corrado’s peace of mind seems heavily contingent upon the ‘progress’ he believes in ‘a little more’ than anything else. One must always be progressing, not necessarily in the sense of improving things, but merely in the sense of forging ahead into something else, something more. Here is the acquisitive, colonialist gaze again – Corrado will soon be plundering South America. Amerigo too cannot contemplate being giusto without immediately dismissing this life goal as ‘too little’ (i.e. there must be more), and Antonioni cannot talk about being at peace with his conscience without immediately saying that he does not know what this means.

Corrado embodies a defining aspect of the world in Red Desert: a confident performance of self-sufficient individualism underpinned (and undermined) by a profound sense of instability; an apparent will towards constant progress which may only be an impulse towards constant change. All this talk about conscience is haunted by a voice like the one we hear in Soleil Ô, railing at these smirking people with their peace of mind and their mindless progress, all of which comes at an unseen cost.

Red Desert does not, of course, contain anything like the moral rage of Hondo’s film, but as we see how Corrado’s philosophy plays out in his professional and personal interactions, that ‘unseen cost’ will become slightly more visible.

Next: Part 22, How to see and how to live.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 456

Mancini, Michele, et al., ‘The world is outside the window’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 173-185; p. 183

Restivo, Angelo, The Cinema of Economic Miracles: Visuality and Modernization in the Italian Art Film (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), pp. 121-122

Nardelli, Matilde, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), pp. 182-183

Ongaro, Alberto, ‘An in-depth search’ (trans. Andrew Taylor), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 344-351; pp. 347-348

Hamilton, Jack, ‘Antonioni’s America’, Look (18 November 1969), pp. 36-40. Available on trussel.com.

Benci, Jacopo, ‘Identification of a City: Antonioni and Rome, 1940–62’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 21-63; p. 34. The definition of ambiente, given in square brackets, is Benci’s.

Pinkus, Karen, ‘Antonioni’s Cinematic Poetics of Climate Change’, Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 254-275; p. 256

Calvino, Italo, ‘The Watcher’ (trans. William Weaver), in The Watcher and Other Stories (San Diego: Harvest, 1971), pp. 1-74; pp. 26-27

Calvino, Italo, ‘The Watcher’ (trans. William Weaver), in The Watcher and Other Stories (San Diego: Harvest, 1971), pp. 1-74; pp. 24-26

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 77

Calvino, Italo, ‘The Watcher’ (trans. William Weaver), in The Watcher and Other Stories (San Diego: Harvest, 1971), pp. 1-74; p. 37. Italian text from La giornata d’uno scrutatore (Milan: Mondadori, 2015).

Calvino, Italo, ‘The Watcher’ (trans. William Weaver), in The Watcher and Other Stories (San Diego: Harvest, 1971), pp. 1-74; p. 37

Calvino, Italo, ‘The Watcher’ (trans. William Weaver), in The Watcher and Other Stories (San Diego: Harvest, 1971), pp. 1-74; p. 39. Italian text from La giornata d’uno scrutatore (Milan: Mondadori, 2015).

Tassone, Aldo, ‘The history of cinema is made on film’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 193-216; p. 215