Everything That Happens in Red Desert (24)

The suitcase and the gyroscope

This post includes some discussion of sexual assault.

We have reached Ugo’s final scene in Red Desert, so this is a good moment to take stock of how Giuliana’s marriage has been portrayed, and how Antonioni appropriates and re-works motifs from earlier fictions that centre on alienated marriages. The flat, muted scene in which Giuliana packs Ugo’s suitcase and is unable to communicate with him is a typically Red Desert-ish reduction of more dramatic, cathartic confrontations in texts and films (including Antonioni’s) that are being subtly alluded to here.

Towards the end of James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, as Gabriel and Gretta Conroy return to their hotel late at night after the party, Gabriel is overcome with desire for his wife:

[A]fter the kindling again of so many memories, the first touch of her body, musical and strange and perfumed, sent through him a keen pang of lust. Under cover of her silence he pressed her arm closely to his side; and, as they stood at the hotel door, he felt that they had escaped from their lives and duties, escaped from home and friends and run away together with wild and radiant hearts to a new adventure.1

But in the hotel room, Gretta is quiet and distant:

He was trembling now with annoyance. Why did she seem so abstracted? He did not know how he could begin. Was she annoyed, too, about something? If she would only turn to him or come to him of her own accord! To take her as she was would be brutal. No, he must see some ardour in her eyes first. He longed to be master of her strange mood. […] He longed to cry to her from his soul, to crush her body against his, to overmaster her.2

Gretta ultimately reveals that she is thinking of a young man, Michael Furey, who died many years ago after ill-advisedly running to see her on a rainy night in winter. Gabriel is deeply shaken by the realisation that ‘she had had that romance in her life: a man had died for her sake.’3

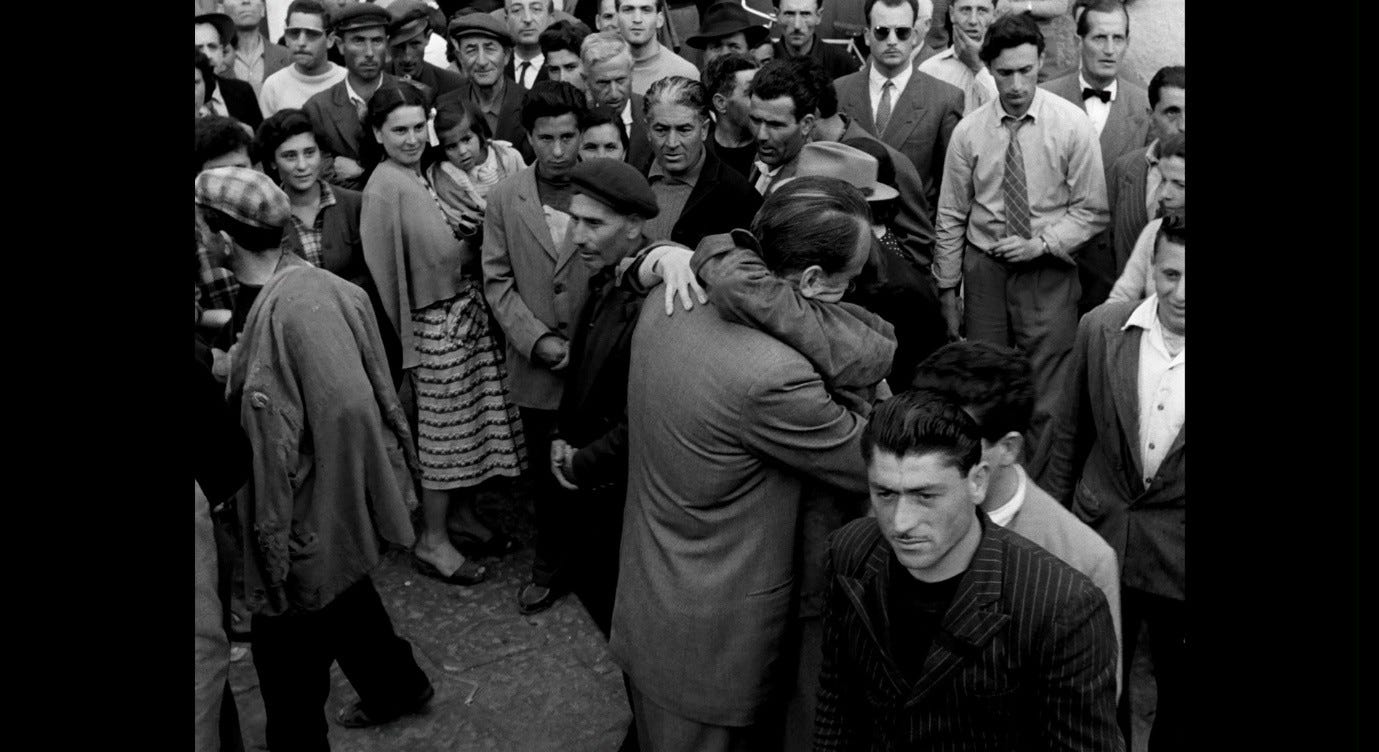

In Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy, a long-married English couple – Katherine and Alex Joyce – have their own version of the ‘new adventure’ Gabriel imagined for himself, escaping from home, friends, work, and duty (‘Do the words “work” and “duty” mean nothing to you since you’ve been here?’ says Alex at one point). But for the Joyces too, the adventure takes a dispiriting turn. Katherine tells Alex about an admirer of hers, a poet called Charles Lewington, who died in a similar way to Michael Furey after calling at Katherine’s window. In this case, the revelation and Alex’s consequent jealousy are part of a larger crisis in the marriage. More isolated and with less to do than at any previous time in their life together, Katherine and Alex see each other as strangers, and they come close to divorcing – but ultimately reconcile in the midst of a religious festival, as the people around them proclaim an (ostensibly unrelated) miracle. Now, the film seems to suggest, these two really might ‘run away together with wild and radiant hearts to a new adventure.’

Rossellini’s film was controversial on its release in 1954: reviled by Italian film critics but lauded by the French New Wave, over time it came to be seen as a pioneering example of ‘modern cinema,’ and especially the kind of cinema with which Antonioni later became associated. Peter Bondanella hints at the link with Antonioni when he says that Journey to Italy

helped to move Italian cinema back toward a cinema of psychological introspection and visual symbolism where character and environment served to emphasize the newly established protagonist of modernist cinema, the isolated and alienated individual.4

L’avventura re-works the Gabriel/Gretta confrontation, most obviously in the scene where Sandro sexually assaults Claudia and then taunts her by saying, ‘Aren’t you happy? You have a new adventure [un’avventura nuova]’ (see Part 11). Like Gabriel, he is frustrated by her unresponsiveness – as he was by Anna’s at the start of the film – and in this case Anna is a kind of equivalent to Michael Furey, the vanished figure from the past who gets in the way of the new relationship.

In La notte, Tommaso is another analogue for Michael Furey: in the confrontation at the end of the film, Lidia describes her dead friend’s devotion to her, and like Gretta and Katherine she seems to feel guilty for not having fully reciprocated his love, as well as regretful about not having seized the opportunities this would-be lover (might have) opened up for her. In death, Tommaso becomes a haunting rebuke to the married couple’s fatuous relationship. He loved Lidia so much, he took her so seriously – perhaps too seriously, she thinks – while Giovanni’s love has become stale and flat, if it is still there at all. Gabriel’s philosophical meditations on mortality, which were transformed into the redemptive communal miracle at the end of Journey to Italy, and then into the tearful sympathy between Claudia and Sandro at the end of L’avventura, find a much grimmer permutation at the end of La notte, as Giovanni assaults Lidia in the sand-trap and she repeats over and over, ‘No, I don’t love you!’

These motifs are present, though less visible, in Red Desert. Once again, we see a marriage in a state of low-key crisis. Even at home, Giuliana and Ugo find themselves becoming strangers to each other, and he responds with frustration and (in the ‘night terrors’ sequence) a desire to ‘be master of her strange mood,’ to ‘overmaster her’ sexually. As in the earlier examples, the crisis is exacerbated and brought to a head by a trip-gone-wrong, a ‘new adventure’ that promises fun but delivers angst and alienation. There is no character equivalent to Michael Furey, Charles Lewington, Anna, or Tommaso this time, but there is a more nebulous absent presence that threatens the characters in similar ways.

When Gretta says, of Michael Furey, ‘I think he died for me,’ Gabriel’s response transforms the dead boy into a kind of spectral monster:

A vague terror seized Gabriel at this answer as if, at that hour when he had hoped to triumph, some impalpable and vindictive being was coming against him, gathering forces against him in its vague world.5

This is the ‘something terrible in reality’ that Giuliana fears, the cry of the dying man, the ship-borne disease that threatens death, the fog that renders the entire world vague. Ugo is not like Gabriel, any more than he is like Dick Diver in Tender is the Night (see Part 23), in that he does not seem to sense or fear this vindictive being coming at him from the fog. Later, as we will see, Corrado is the one who takes on some of these anxieties. But primarily we see them from Giuliana’s point of view. The film evokes her sense of being haunted, not by a specific lost love or lost connection (or lost opportunity for connection), but by the existential dread that lay behind those other relationship crises.

As Gabriel falls asleep beside his wife, there is a blurring-together of what he sees through the window and what he sees in his mind’s eye. Some of the imagery here anticipates the out-of-focus effects in Red Desert:

The tears gathered more thickly in his eyes and in the partial darkness he imagined he saw the form of a young man standing under a dripping tree. Other forms were near. His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself which these dead had one time reared and lived in was dissolving and dwindling. A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again.6

To be conscious of something you cannot apprehend is like the feeling Giuliana expresses when she says, later in Red Desert, ‘there is something terrible in reality, and I don’t know what it is.’ In ‘The Dead’, this failure of apprehension is less terrible, more resigned. The creature from the earlier passage, that ‘impalpable and vindictive being, gathering forces against him in its vague world,’ has dissipated into the more nebulous ‘form’ of Michael Furey (now an anonymous ‘young man’) accompanied by ‘other forms,’ the ‘vast hosts of the dead.’ These forms’ ‘wayward and flickering existence’ makes me think of the shaky telephoto-lens shots in Red Desert’s title sequence, reducing solid objects to amorphous shapes, just about recognisable as ‘forms’ of trees and factories, but with their specific identities fading away. Here, though, Gabriel sees these dissolutions as he falls asleep, not as part of a waking nightmare. The vindictive creature’s ‘vague world’ has become the ‘grey impalpable world,’ no longer so vague or threatening because now it seems more universal, like the snow that is ‘general all over Ireland,’7 as much a comforting blanket as a burial shroud.

The ‘solid world,’ Gabriel muses, was made and inhabited by past generations, and now it is dissolving just as they have dissolved. In Red Desert, Giuliana inhabits a newly built ultra-modern world, inhabited by a new species of ultracorpi, but she also sees the ‘old world’ in the Via Alighieri, flaking away into ashes along with its scowling, anonymous denizens. Gabriel Conroy complains, in his speech at the party, about the new ultra-educated generation outstripping the old and losing touch with old-world values,8 but he also feels himself – and youth itself, embodied in the ever-young but ever-vague form of Michael Furey – being taken over by the realm of shades. There is the sense of being ‘left behind’ by the world progressing relentlessly around us, but there is also the sense of being haunted by the long-dead who were left behind in their turn. For Gabriel, this crisis seems to resolve itself – and to lull him to sleep, which is next door to death – in a feeling of communal absorption. The fact that we are ‘all becoming shades’9 binds the living and the dead together rather than setting them in conflict.

Journey to Italy likewise revolves around and resolves itself in a feeling of unity between the living and the dead, but in a way that leans towards the ‘living’ end of the spectrum, transforming the shades back into living, palpable beings. As Rossellini said in an interview:

[Katherine] is always quoting a so-called poet who describes Italy as a country of death – imagine, Italy a country of death! Death doesn’t exist here, because – it’s so much a living thing that they put garlands on the heads of dead men. There is a different meaning to things here. To them death has an archaeological meaning, to us it is a living reality. It’s a different kind of civilization.10

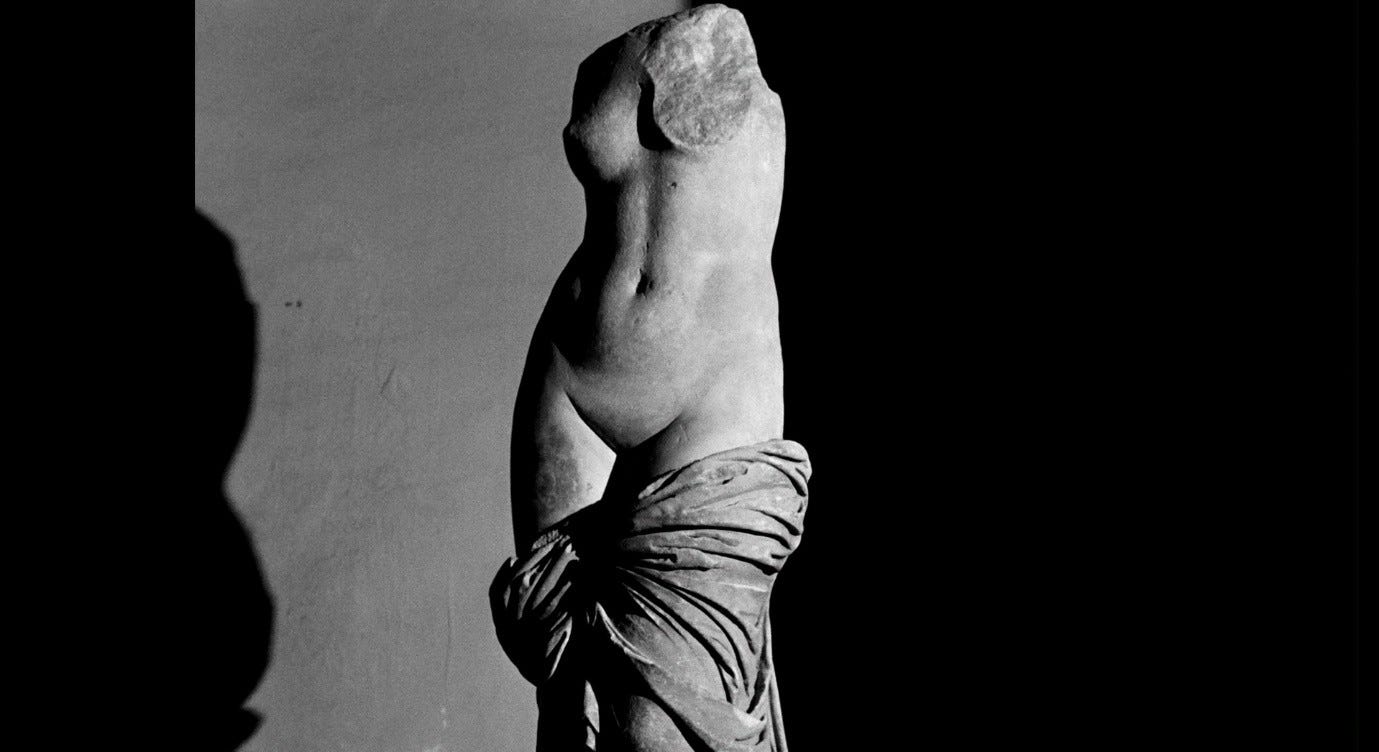

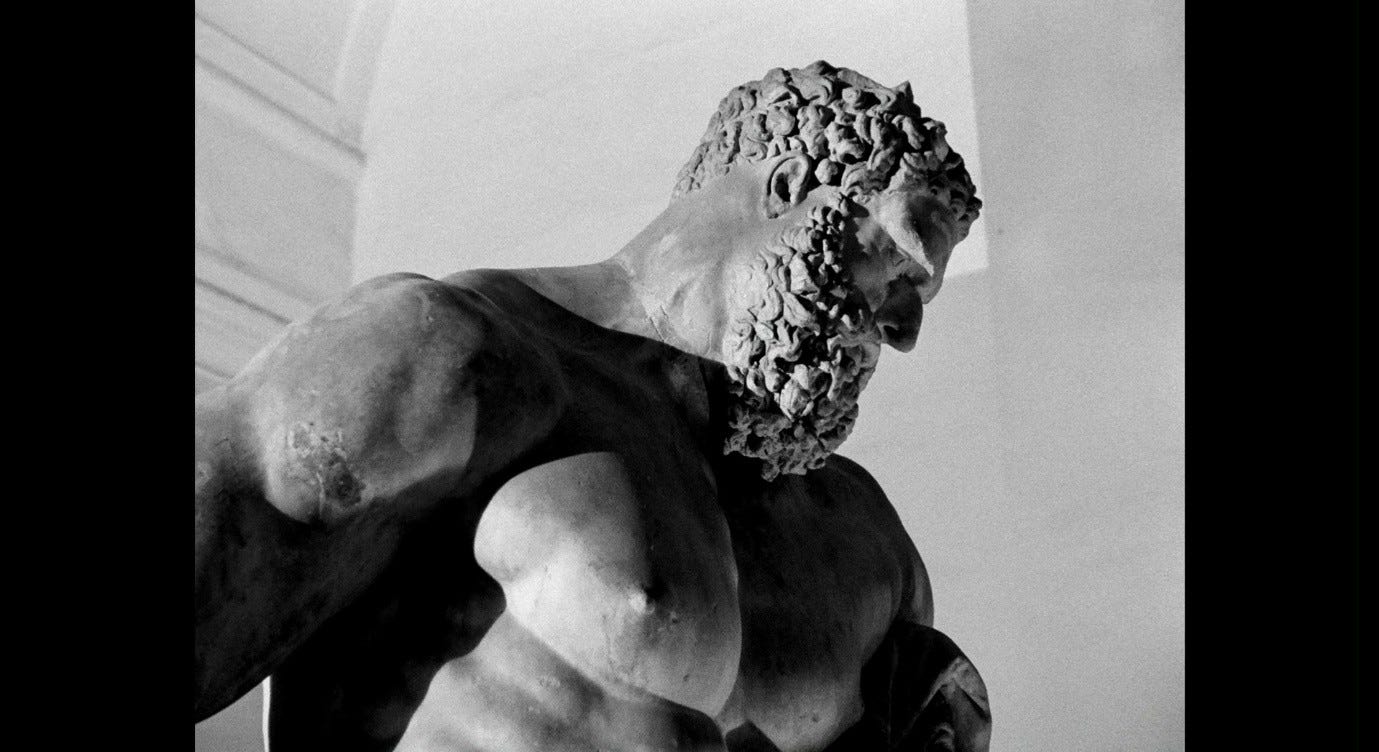

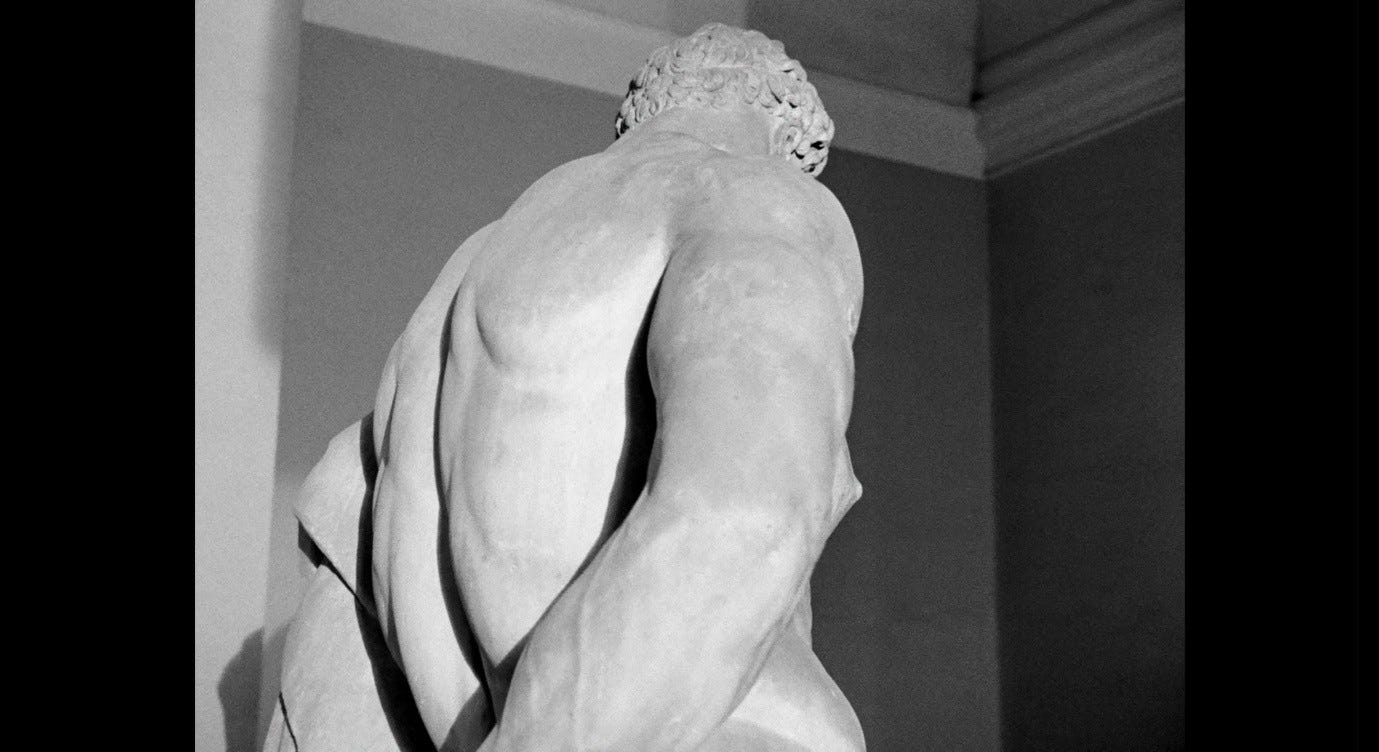

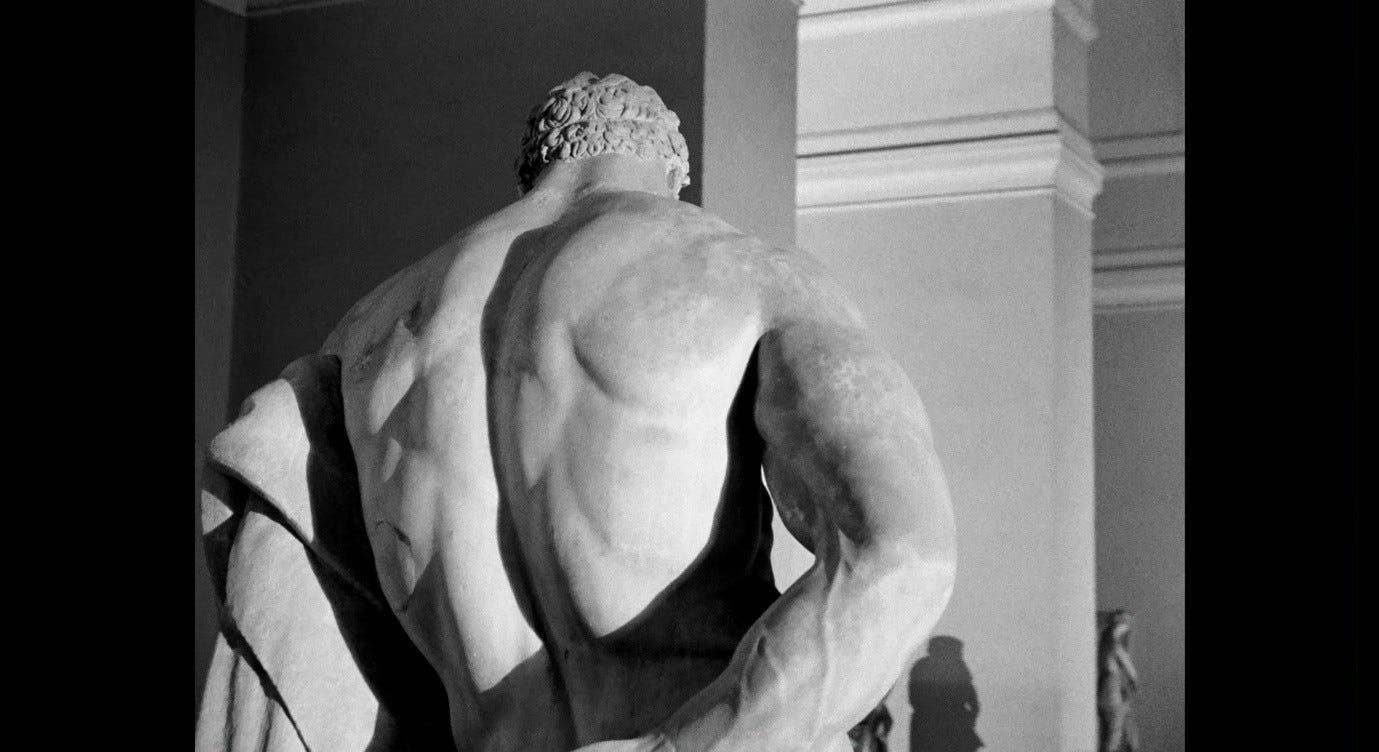

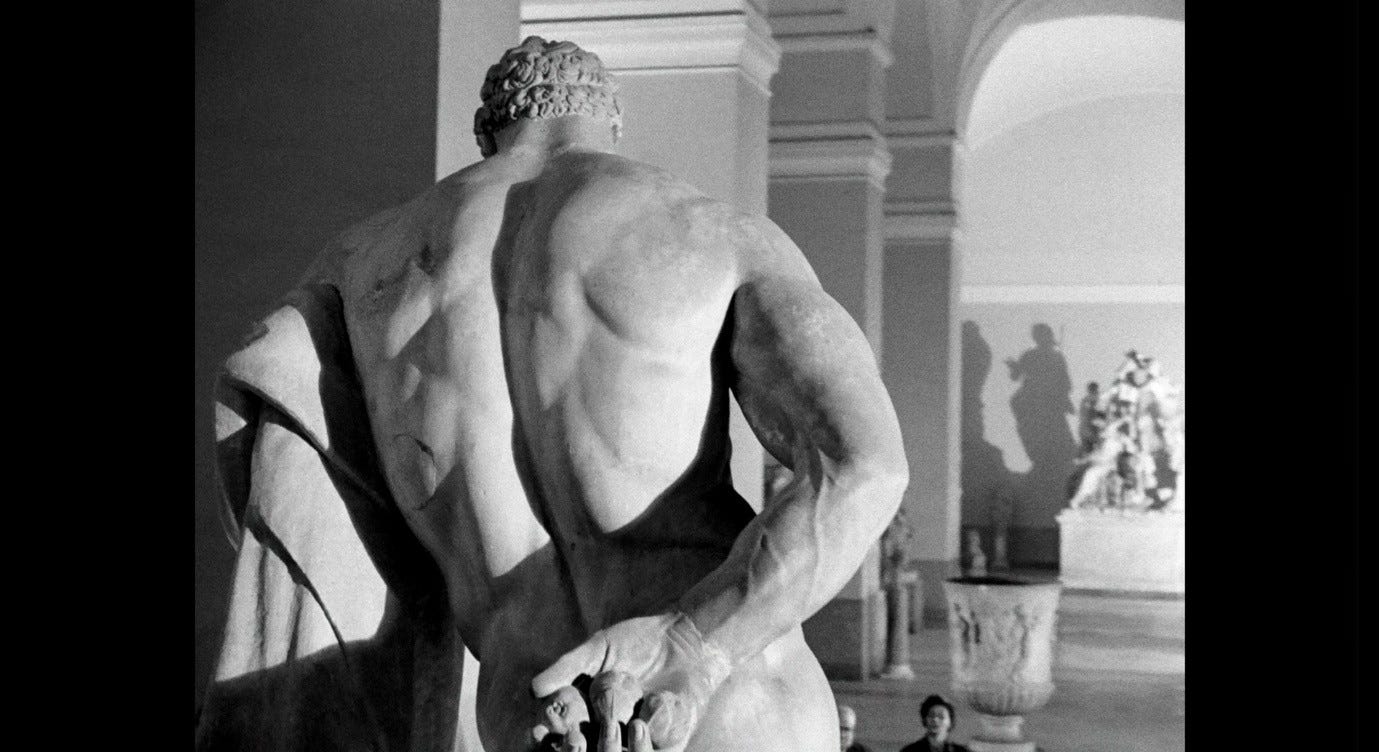

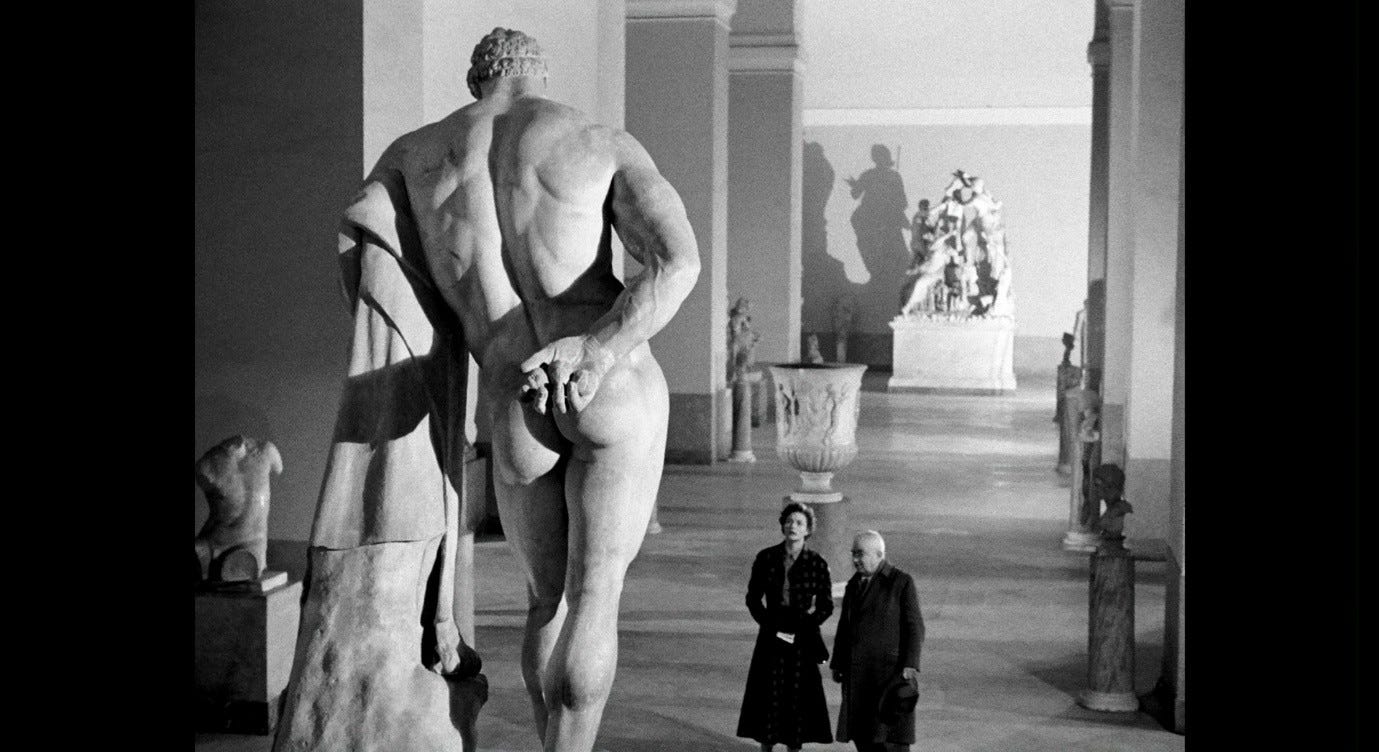

‘Temple of the spirit,’ writes Charles Lewington in the poem quoted by Katherine, ‘no longer bodies but pure ascetic images, compared to which thought seems flesh, heavy, dim.’ When Katherine sees the sculptures Charles was writing about, she finds them all too alive, not ascetic but brazenly corporeal. Although they are made of stone, they are so vivacious that the flesh of Katherine and Alex seems heavy and dim by comparison, too ‘thought-tormented’11 (as Gabriel Conroy might say) to be capable of sensual pleasure.

But the significance of Charles’s verses becomes more nuanced as the film goes on – more nuanced than Rossellini’s reductive description of them. Joseph Luzzi argues that

it is the dream of Lewington’s highly sublimated Italy – the corollary for the pure, noble love he evidently felt for Katherine – that leads her along, his verses the mantra that might save both her marriage and her soul.12

If at first the poem seems misguided in reading the sculptures as ‘pure ascetic images,’ as spiritual temples divorced from earthly desires, later it seems to partake of the ‘living reality’ of death as Rossellini describes it, ascribing life and spirit to stones and images, but not to the flesh or thought of those who are nominally ‘the living.’ The poem is an incoherent declaration of love for the artworks Charles discovered in Naples, containing within it (as Luzzi points out) a sublimated expression of love for Katherine herself, so that she sees herself, or the mystery of Charles’s love for her, mirrored in these ‘temples of the spirit.’

To him, she transcended the ordinary world of the living; now, with his words echoing in her mind, she finds herself on a transcendent journey of self-discovery among the dead.

In the excavation at Pompeii, at the height of their marital crisis, Katherine and Alex – dark figures framed against a light sky – look down at the plaster casts of the dead couple – white figures framed against the dark earth – and Katherine cries out in distress and runs away.

Noa Steimatsky describes the emotional resonance of this encounter:

For an excruciating moment the plaster casts appear as mirror images of the protagonists who, gazing down as if at their own reflections in an open grave, encounter the fearful, static symmetry of death that, as the framing and editing suggest, returns their look. […] Confronted by this mirroring – or as in a photographic negative where distinct features are not immediately discernible – one recognises in this instant the allegorical figure of death hovering in the optical surface. Indeed, the photographic image itself finds in the unearthed Pompeiian couple its ancient forebear: a positive replica of a negative imprint that has arrested living motion and is brought to light in an elaborate process, unfolding in time.13

But as well as confronting the characters with their own mortality and hollowness, as Steimatsky argues, the plaster bodies are also lifelike in a way that rebukes the living. Just as a mirror reverses what it reflects, so the dead in this scene become ‘alive’ as they ‘return the look’ of those who have discovered them. Their naked white arms reach upwards as though in greeting, as though to embrace the onlookers, who seem, in Luzzi’s words, ‘immobile, embalmed, and sterile’ by comparison.14 ‘[W]hile the images of the people of Pompeii were preserved at the moment of death,’ says Laura Mulvey, ‘film is able to preserve the appearance of life.’15 In the scene at the museum, ‘the camera brings the cinema’s movement to the statues and attempts to revitalise their stillness,’16 again making the dead seem more alive than the living.

Rossellini wants us to feel that something miraculous is happening, akin to the revival of Lazarus, paving the way for the miracle of the revived marriage in the final scene.

Red Desert presents a kind of mirror-and-reversal of Journey to Italy. Rossellini may have regarded Italy as a land where death did not exist, but Antonioni sees death everywhere. When he films sculptures, as we saw in Part 14, he fixates on their blindness and how it mirrors his own. Giuliana hears a death rattle from outside Max’s shack, then even this grido seems to fade into oblivion, in a chilling parody of Rossellini’s comment about death not existing. Someone really died within earshot of Giuliana, and there really was a cry, just as there really were two bodies in the long grass outside that bowling alley on the Tiber (see Part 20). The way in which these facets of reality can be ignored, the way in which ties between people can be dissolved, suggests a complete rejection of Rossellini: not only do we not put garlands on the dead, we do not even notice them dying. And then, far from bringing cold sculptures to warm life in the sunshine of southern Italy, Antonioni’s camera freezes his characters in the fog of northern Italy. Compare Giuliana looking at her friends in the fog to Katherine looking at those statues in the museum.

In Red Desert there is no temple, no spirit, only bodies that, far from being ‘no longer bodies,’ are nothing but bodies. Katherine thought the sculptures would come to life and interact with her; Giuliana cannot find a trace of human connection in these fog-shrouded ‘people’. Luzzi describes the break from Neorealism represented by films like Journey to Italy and L’avventura in a way that deepens the significance of the link to ‘The Dead’:

Rossellini’s and Antonioni’s characters enjoy the privilege of wavering over emotional ambiguity and personal entanglements – a luxury inconceivable to the partisans of Rossellini’s Open City. When Antonioni claimed that Italians should no longer make films about a man who has had his bicycle stolen [see Part 16], the admission was bittersweet: though most Italians of the 1960s didn’t suffer the hardships depicted in films of the 1940s, they also had lost many of the moral and ethical certainties and much of the collective sense of engagement of the immediate postwar years. Matters between wealthy couples like Katherine and Alex, Claudia and Sandro, could become so complicated that they would remain together out of habit, circumstance, obligation, fear of being alone, or – here lies the genius of the films – a vague combination of all of the above. Did all those Italian patriots in Rossellini’s war trilogy from the 1940s die for this: the unfathomable subtlety and complexity of human intimacy?17

The rhetorical question at the end of this passage receives a kind of answer in Red Desert. What do people die for, and if they survive what do they live for? Michael Furey and Charles Lewington died for love, but what does that mean as time passes and the lovers-who-survive become more and more like shades of their earlier, more passionate selves? Patriots die for their country, for the sake of moral and ethical certainties, in the service of a collective sense of engagement, but what does that mean as time passes and the economy recovers and the patriots-who-survive become prosperous industrialists (or, like Giovanni in La notte, artists who work for industrialists)? Would these emotional ambiguities have been inconceivable to the partisans of Rome, Open City, or would it simply have been indecorous for Rossellini to acknowledge them in that context? When Pina and Francesco cried out each other’s names and she was shot dead in the street, in that moment did they see each other through a kind of fog and wonder what they had ever meant to each other? Did Pina choose to dash into the street and be killed because, on some level, like Giuliana on the pier, she felt death and oblivion crowding in on her and just wanted to escape from that existential terror? Was she afraid of surviving and having to live on with Francesco, staying with him out of a vague combination of internal and external pressures, failing to communicate with him, packing his suitcase, still sensing the presence of death (and the dead) all around them?

For Joyce’s and Rossellini’s couples, and even for the couples in L’avventura and La notte, there is a kind of resolution, however ambiguous. Each story ends with the characters coming to terms with the crisis they have faced, even if they do so separately (like Gabriel and Gretta) or in violent conflict with each other (like Giovanni and Lidia). In Red Desert, Giuliana’s marital crisis reaches a peak just over halfway through the film, and after a brief scene back at home, Ugo leaves and is never seen again. What if ‘The Dead’ were narrated from Gretta’s point of view, and she were unable to tell Gabriel about Michael Furey, or he were unable to listen or understand, going on with the mundane business of his life while she agonised over her own disintegration?

For Joyce and Rossellini, there is a sense of warmth and even joy to be derived from the confrontation with mortality. Everything dissolves, including these marriages, but that awareness of death brings the couples closer as well as separating them. Despite Gabriel’s frustration, we may feel that he and Gretta will be happier together from now on, and Katherine and Alex seem ‘brought to their senses’ by the prospect of losing each other, spurred into greater intimacy by the very alienation that has afflicted them during their Italian adventure. But Ugo just leaves, and Giuliana just packs his bag. Ugo will be referred to once more, in the next scene, but otherwise he will henceforth be an absent absence. There will be no sense at all that he and Giuliana miss each other.

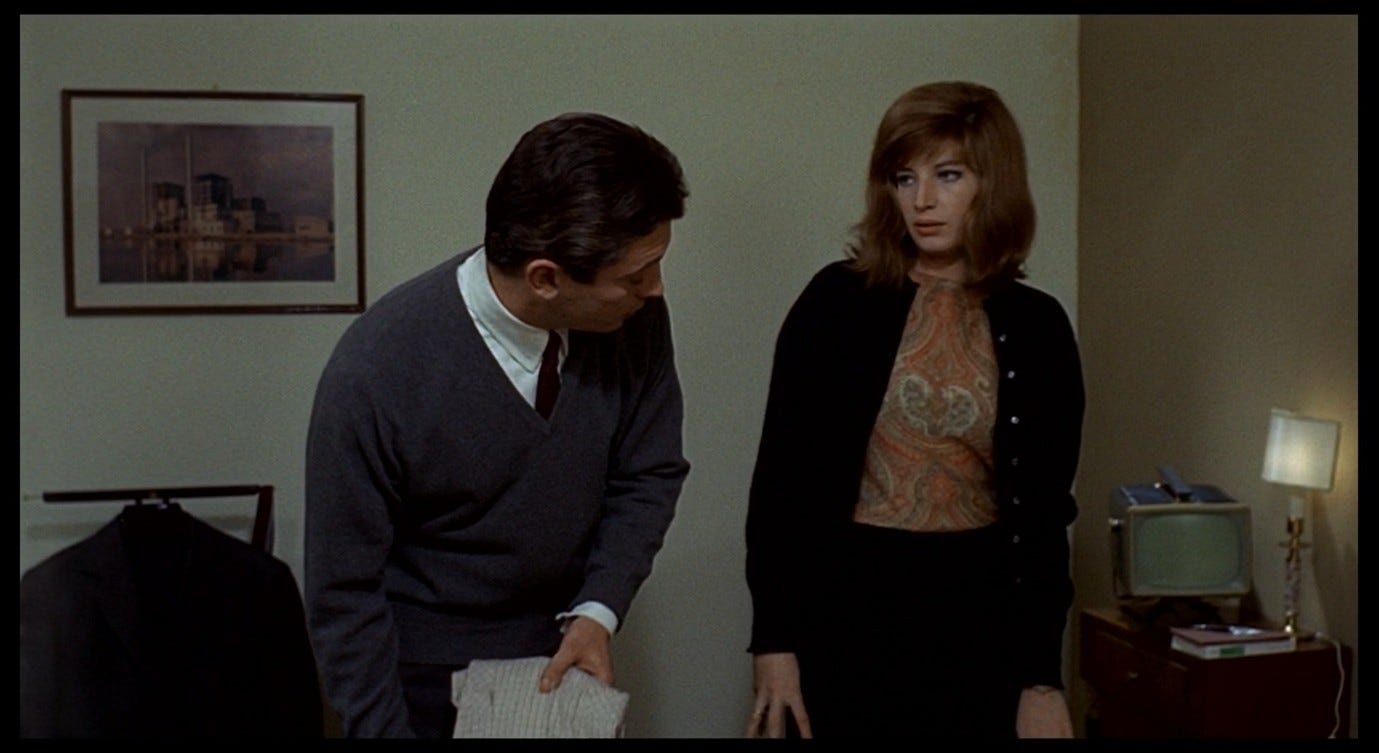

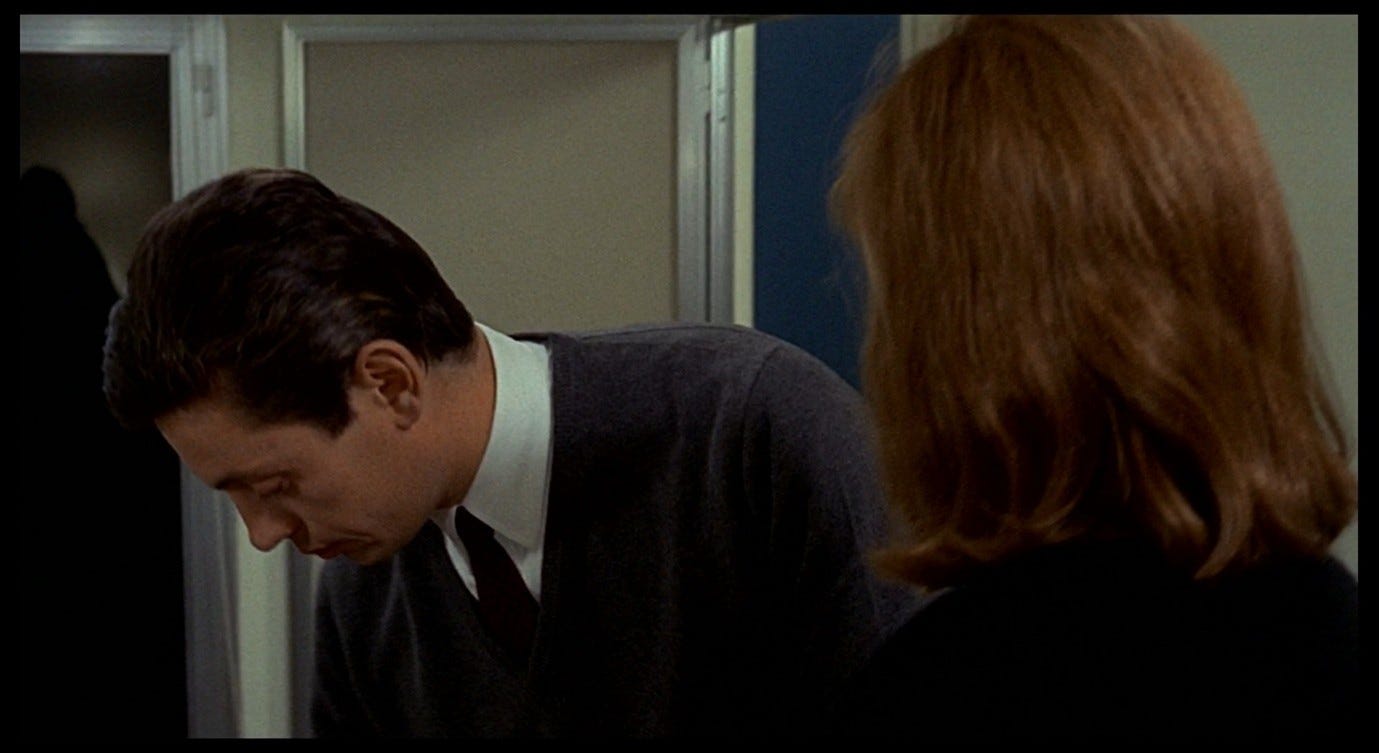

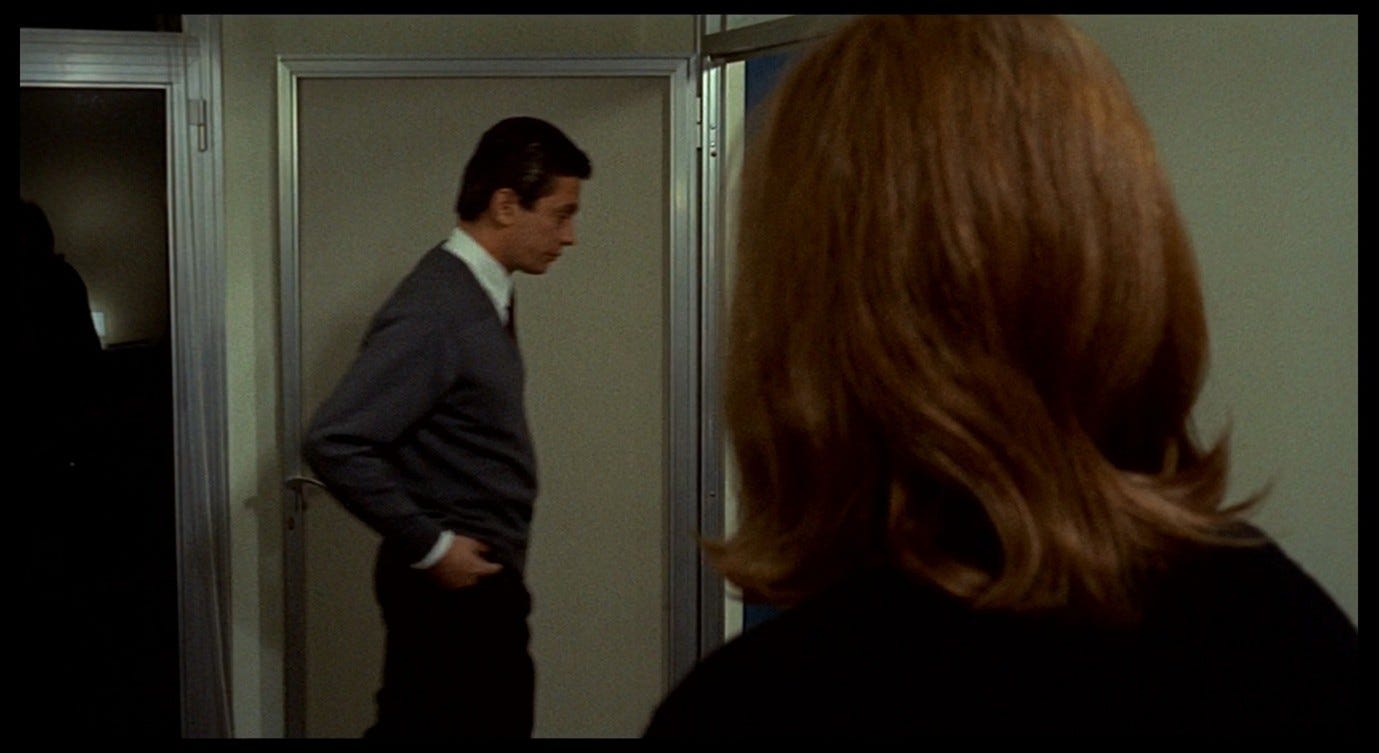

As Giuliana packs Ugo’s shirts, he comes into the bedroom and proposes an idea: while he is gone, Linda could stay in the apartment with Giuliana. When Ugo says this, his face is blank (the smile from the previous scene is completely absent in this one) and his tone is flat, rising strangely on the final word ‘here [cui]’ as though in a hasty effort to sound casual. He joins Giuliana by the bed, where the suitcase lies open. As she straightens to look at him, he bends down to pack some more clothes.

When she asks ‘Why?’ he explains that he wants someone to be there in case Giuliana wakes up in the night. When he starts speaking, he is looking down at the suitcase, but as he reaches the end of the sentence he turns to look at her and stands up straight.

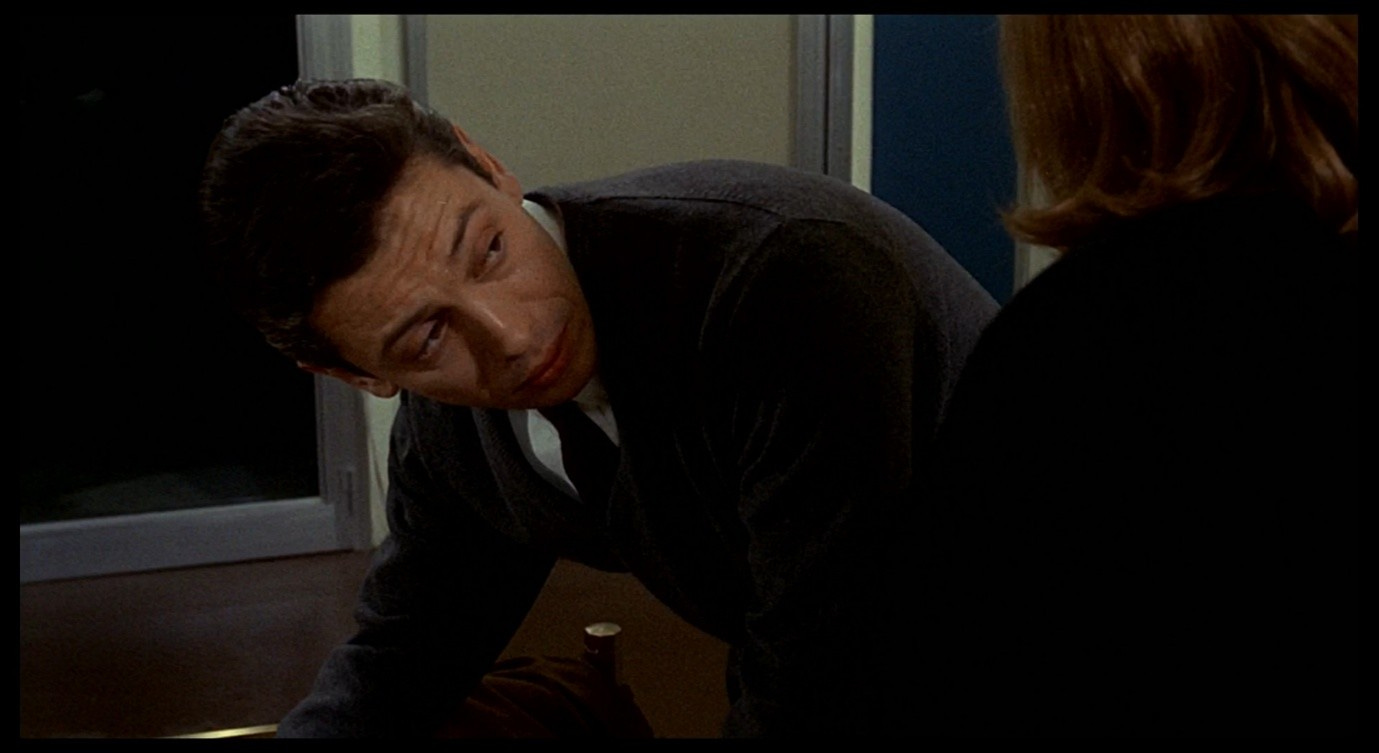

He is noticeably taller than her. Once his gaze meets hers there is something penetrating about it: he looks down at her fixedly, coldly, examining her reaction. There is a subliminal visual rhyme with Ugo looking down the eyepiece of the microscope a few moments earlier. He is observing Giuliana carefully and he is saying that she needs to be observed.

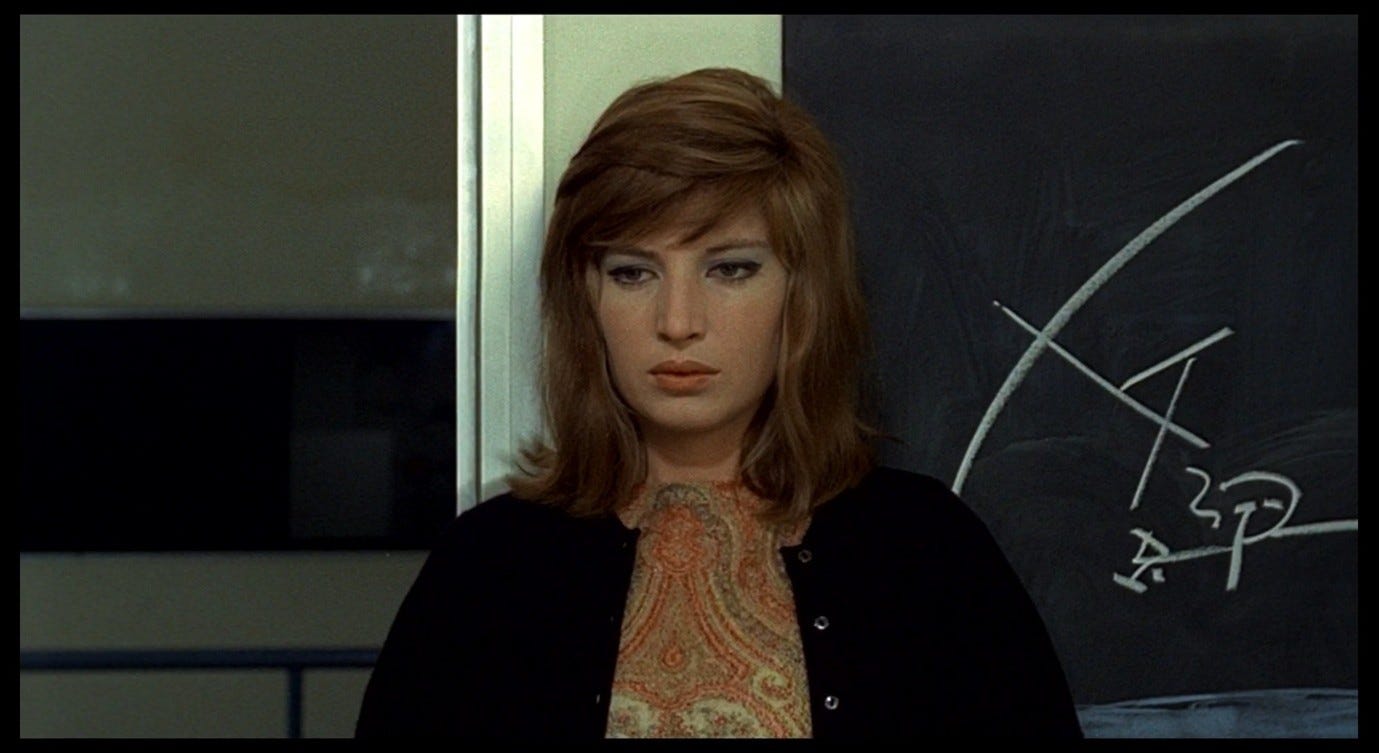

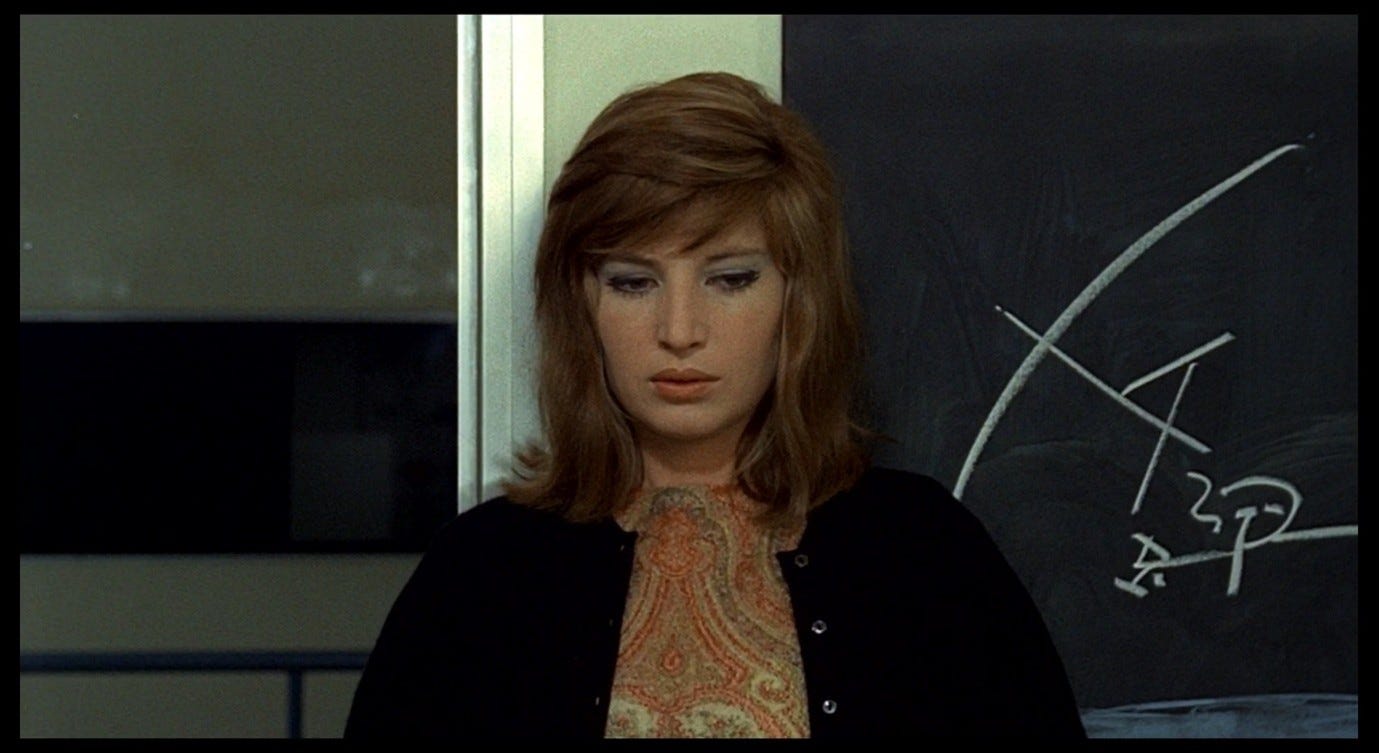

She seems to crumble beneath his gaze, her eyes darting around nervously.

As she agrees to invite Linda over, she bends down to continue packing. Ugo remains upright, still staring at Giuliana, with a look on his face that could convey pity, contempt, bemusement, repressed concern, or a combination of all these.

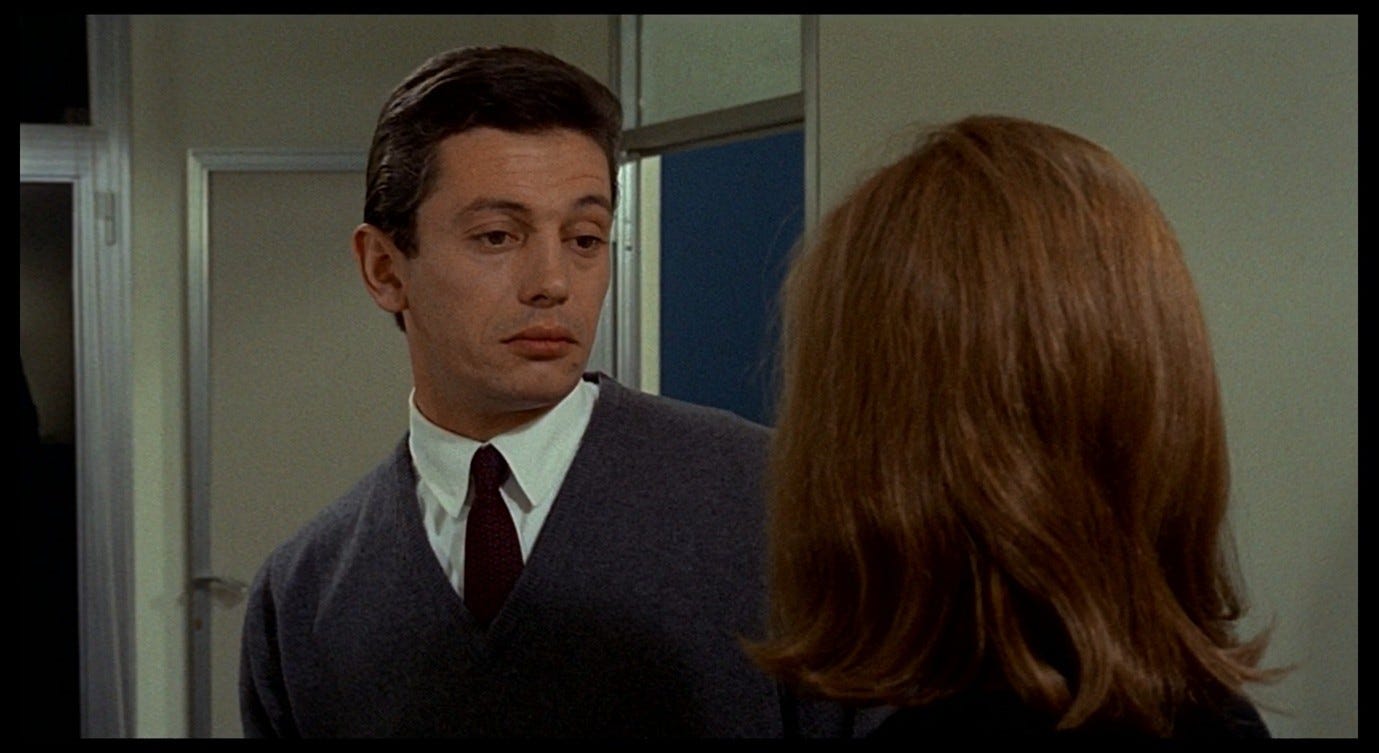

As he walks away, Giuliana snaps upright and says, ‘But maybe it’s better not to.’

The screenplay comments on her motivations here. First, she agrees with Ugo’s proposal because she has ‘perfectly understood his concern.’ Then she becomes absorbed in the suitcase ‘to conceal her turmoil [turbamento].’ Then she retracts her agreement because she is afraid of giving the impression ‘that she is indeed still unwell.’18

Ugo immediately nods, moves his lips without speaking, and puts one hand in his pocket as he leaves the room.

Both characters are working hard to appear casual and both use the suitcase as a prop to hide or distract from the emotions underlying their conversation. They are carefully folding and packing away their feelings, but they are also very aware that they are doing this. Earlier in the film Ugo tended to Giuliana during her night terrors by trying to make love to her, as though her anxiety were merely a symptom of libidinal frustration, a bodily tension that could be eased with sex. Things are more serious now: she has had another near-fatal driving incident and there is no telling what she might do if left unsupervised. Ugo is perhaps leaving because, having found that sex cannot help Giuliana, he feels unable to help her in any other way. As long as someone is around to stop her from harming herself, it does not matter who that person is. Ugo’s ‘love-making’ was more like sexual assault, an action pursued robotically in spite of Giuliana’s visible discomfort and ‘rejecting’ hand-gestures (see Part 11). His solicitous behaviour in the present scene is not aggressive, but it has a similarly robotic quality: again, Ugo does not seem to engage with Giuliana as an individual, but as a problem to which a formulaic solution must be applied.

Giuliana’s eagerness to appear well in front of Ugo and her horror at being thought of as unwell are prompted by his attitude towards her. When we first met Ugo, he expressed his frustration at Giuliana’s failure to ingranare (to get in gear), and also at her attempt to set up a shop, which did not seem decoroso to him. His sense of decorum and propriety forbid any open discussion of mental illness, but they also make it impossible for him to overlook or ignore Giuliana’s indecorous behaviour. He has to make sure she is watched by someone responsible while he is away, so she has to agree to this precaution. But he also cannot help but think less of her for needing to be watched, so she has to say that she will be fine on her own. Then he has to nod casually in agreement, as though there were nothing to worry about, but he also cannot help imbuing this gesture with a tone of passive aggression, as if to say that it is her funeral if she will not accept help. Then he has to run away on a work trip, because otherwise the only thing left to do is to really see what his wife is going through and really talk to her about it.

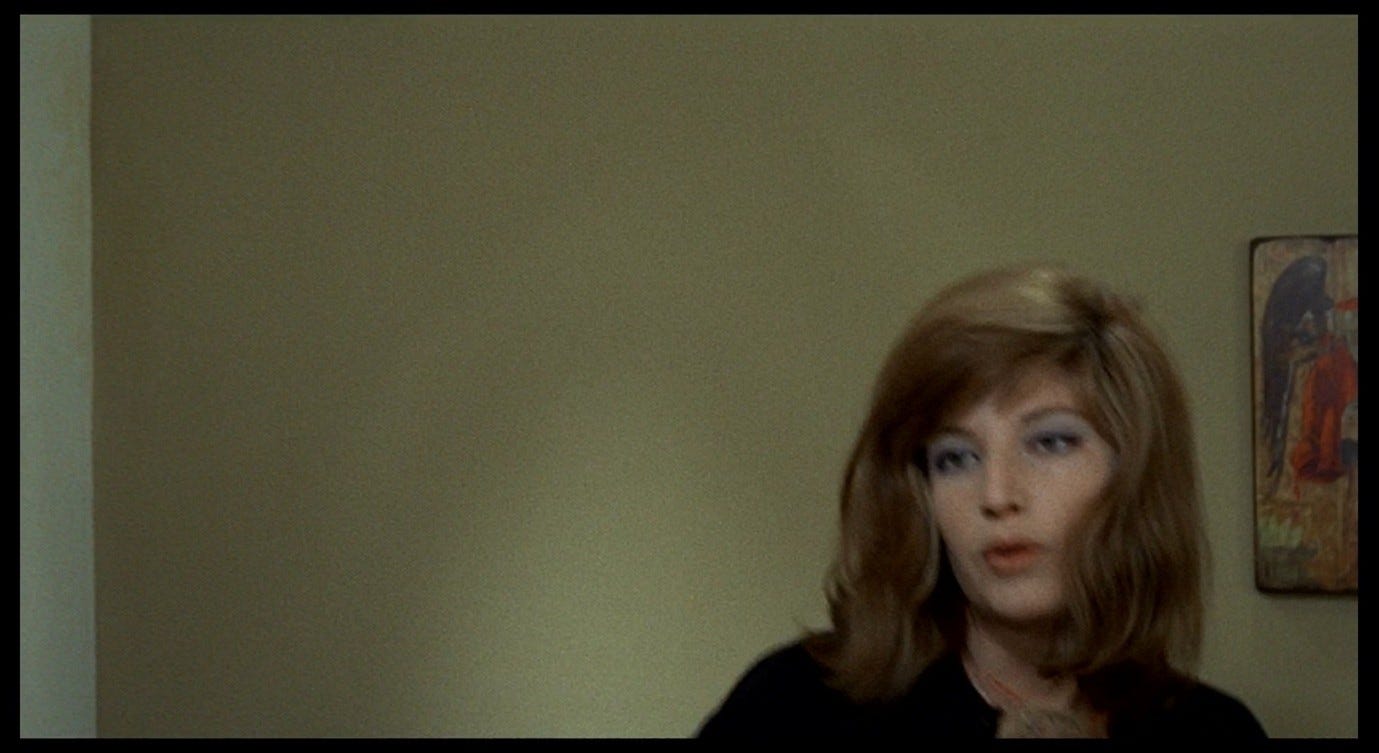

After Ugo has left the room, Giuliana continues to look at the space he has just vacated, her face still fixed in an expression of dismay.

She seems aware of having disappointed him, of having been unable to respond appropriately, but throughout this conversation she has also given the impression that she is silently pleading with Ugo, desperate for him to look at her and talk to her in a different way. Her eyes dart around once more and she tries to resume packing. The sound of a foghorn interrupts her and makes her look up.

It perhaps reminds her of the incident on the pier, the event that precipitated her husband’s departure: somehow, she cannot pack his suitcase while listening to that noise, so she returns to Valerio’s bedroom, leaning in the doorway with Gianni Dova’s Rite of Spring visible to her right.

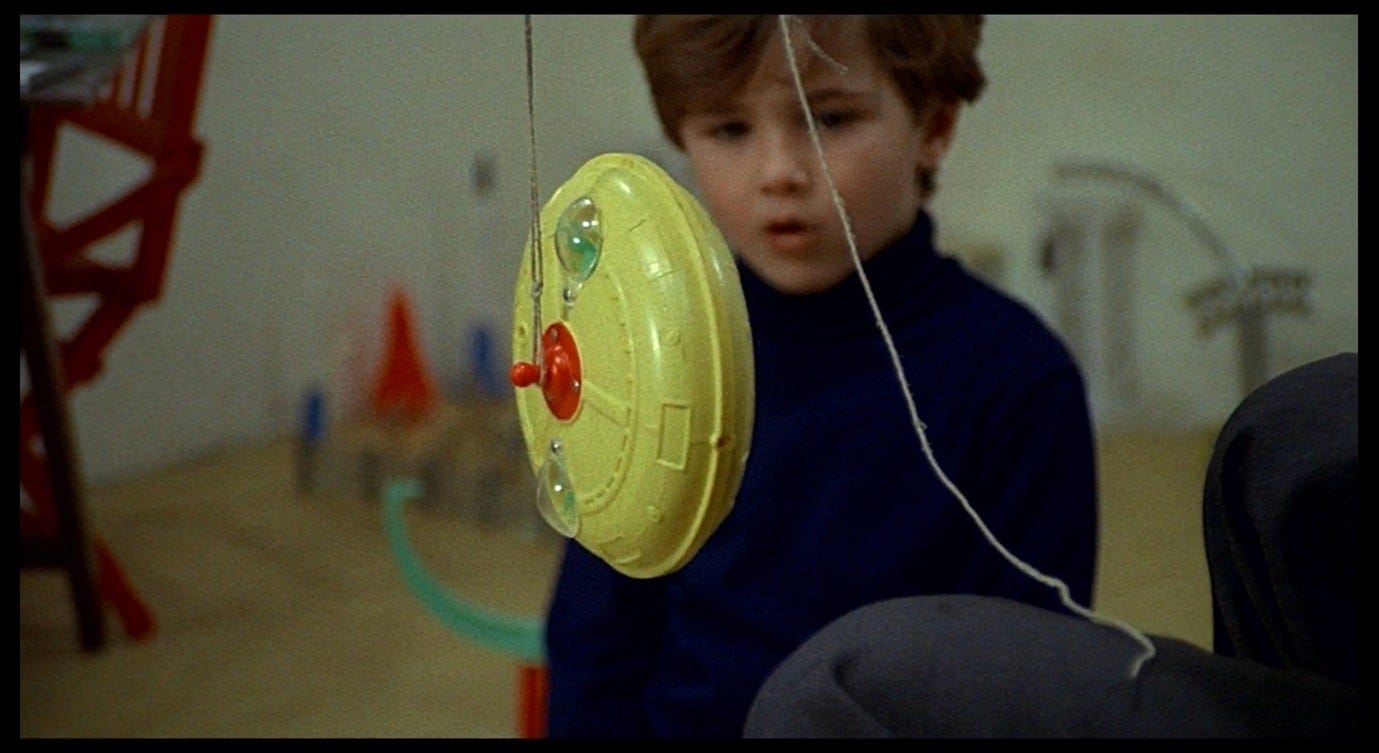

The sequence ends where it began, and with a similar set-up: Ugo and Valerio are bonding over a new toy while Giuliana hovers on the threshold, watching anxiously. The camera begins at a low angle, on the level of Valerio’s eye-line, with him and Ugo in focus and Giuliana out of focus in the foreground. The dolly movement excludes her altogether, giving us a clearer view of Valerio and framing him against an elaborate metal contraption that seems to stretch out its arms, warning Giuliana to keep away.

All but one of the subsequent shots in this sequence will focus on the two male characters. For a brief moment we will see Giuliana looking down at them, her eyes moving from one to the other, now without a trace of a smile. This is another game that excludes her, another scientific demonstration that throws her predicament into relief.

‘Look how beautiful [Guarda che bello],’ Ugo says as he holds up the new toy, echoing his earlier ‘Ooh, che bello’ when looking through the microscope. His tone is different now, no longer filled with the wonder of discovery but instead calmly instructional. Here, he seems to be saying, is a thing that should be understood and appreciated. The gyroscope inside the toy is designed to be used in ships, to keep them upright when the sea is turbulent (or cattivo, as Ugo calls it). This thing is beautiful because of its stability, specifically because of the stability it lends to the ships that keep Ugo’s business functioning. These are the criteria that define what is bello and what is cattivo in this world.

Ugo winds the toy and places it on the floor so that it can spin autonomously. Then he tells Valerio to place it on its side so he can see how it will right itself. The toy travels around the room, responding to each surface it bumps into and adjusting its course appropriately.

The toy is another robot to add to Valerio’s collection: like the humanoid robot, it is capable of patrolling under its own power and also capable of guarding him from danger. Linda may not be able to keep Giuliana in a stable condition – and Giuliana may not accept the support anyway – but Valerio will not be dragged under by his unstable mother.

The two transparent hemispheres on the upper surface of the toy resemble eyes (with a red nose between them), but they also contain little blue action figures.

Like the workers clambering around the Medicina Radio Observatory, these figures have become absorbed by a machine, their sensory capacities outstripped by those of the equipment they operate.

The observatory reaches into space to listen to the stars; Valerio’s toy seems designed to explore the sea, traversing both the surfaces and depths of the ocean with ease thanks to the perfectly calibrated gyroscope. The kneeling child towers over this piece of equipment, he and his father seeming to represent a new race of people who have mastered the art – or the science – of exceeding human proportions.

Giuliana stands to one side, looking down at the two boys and their new robot, processing what this means for her. The gyroscope maintains stability even in the roughest of seas, whereas she cannot even look at the sea without disintegrating, cannot even maintain her composure when she hears a foghorn. The gyroscope rotates in an orderly manner and responds calmly and confidently to its environment, whereas she cannot decide which way to turn or where to look, whether to pack the suitcase or watch Valerio play, whether to invite Linda over or brave the night terrors by herself.

The toy has a mind of its own but no feelings. You play with it by setting it off and then leaving it alone. Like the marching robot, the spinning one whirrs and clicks ominously as it moves about the room. Ugo explains its function in his typically flat tone while Valerio watches in silence, again following his father’s example (and instruction) to guarda. The chilling tone of this exchange anticipates the chilling penultimate shot of The Passenger, in which the gyroscopes attached to the camera ‘completely neutralised the bumping and swaying’19 as it travelled through the bars of the hotel window, leaving behind the soon-to-be-dead protagonist. ‘Look how beautiful,’ the film seems to say, dangling the serene camera in the air as our hero is killed off-screen.

In Journey to Italy, we watch Katherine and Alex looking down at the plaster bodies in Pompeii, and feel the transformative effect of this reciprocal ‘look’ between the two couples. As unaffected as Alex pretends to be in the immediate aftermath, he clearly shares something of Katherine’s emotion. This shared revelation erupts, breaking through this English couple’s repression, a few minutes later as the film ends. They have seen something together, and eventually they come to terms with it together.

In the gyroscope scene of Red Desert and in the preceding daytrip sequence, the verb guardare has been foregrounded repeatedly. In Max’s shack, Giuliana fretted over the question, ‘what should I look at?’, feeling (like Katherine Joyce) helplessly engaged, involved, and transformed by the objects of her gaze. The gaze of Ugo and Valerio is, like the gyroscope, immune to such engagement, involvement, or transformation. It is steady, detached, unfeeling, and lifeless. Their eyes might as well be operated by the little blue men inside the toy. Murray Pomerance’s comment about Ugo, that the gyroscope ‘could be torn from his own interior,’ applies just as much to Valerio.20 These eyes are not just better and stronger than Giuliana’s, they are blind to her and to the things she sees. In the next scene, out on the ocean with Corrado, she will reflect on her husband’s failure to see her and on her new friend’s apparent receptiveness to what she is showing him.

Next: Part 25, The island of SAROM.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; p. 216

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; p. 218

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; p. 223

Bondanella, Peter, The Films of Roberto Rossellini (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 111

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; p. 222

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; pp. 224-225

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; p. 225

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; p. 204

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; p. 224

Luzzi, Joseph, ‘Rossellini’s Cinema of Poetry: Voyage to Italy’, Adaptation 3.2 (2010), pp. 61-81; pp. 66-67

Joyce, James, ‘The Dead’ (1914), in Dubliners (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 174-225; pp. 192, 204

Luzzi, Joseph, ‘Rossellini’s Cinema of Poetry: Voyage to Italy’, Adaptation 3.2 (2010), pp. 61-81; p. 71

Steimatsky, Noa, Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 76

Luzzi, Joseph, ‘Rossellini’s Cinema of Poetry: Voyage to Italy’, Adaptation 3.2 (2010), pp. 61-81; p. 74

Mulvey, Laura, ‘Vesuvian Topographies: The Eruption of the Past in Journey to Italy’, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real, ed. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (London: BFI Publishing, 2000), pp. 95-111; p. 98

Mulvey, Laura, ‘Vesuvian Topographies: The Eruption of the Past in Journey to Italy’, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real, ed. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (London: BFI Publishing, 2000), pp. 95-111; p. 104

Luzzi, Joseph, ‘The End of the Affair: Rossellini and Antonioni after Neorealism’, Raritan 33 (2013), pp. 105-119; p. 118

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 478

‘Antonioni on the Seven-Minute Shot’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 125-126; p. 126

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 90