Everything That Happens in Red Desert (33)

Valerio's paralysis

This post contains discussion of child suicide and spoilers for Germany Year Zero, The Night of the Shooting Stars, and Cría Cuervos.

When Valerio claims, one morning, that his legs are paralysed, Giuliana teasingly suggests that he is only faking illness to avoid going to school. It turns out that he is faking it, but Red Desert is not the kind of film to ascribe a straightforward motive – like playing truant – to such behaviour. This trick, even more so than Valerio’s ‘one plus one’ joke in the earlier scene, carries an enormous weight of meaning for Giuliana. Whether intentionally or not, Valerio is commenting on his mother’s state of mind and on her disintegrating relationship with him, with her husband, with their home, and with the world in general. He may be surprised by her reaction to his trick – he may have expected her to be angry, rather than to run away in terror – but we are not. The scene is, in part, about the tension between the commonplace childish ruse that has been committed and the searing existential wound that it inflicts. Most people might not feel this wound as keenly as Giuliana does, and yet the film does not suggest that she is imagining it or overreacting. We are on the Hermann Broch plane of reality, where the ‘idle play’ of children can stand for the collapse of all human connections.

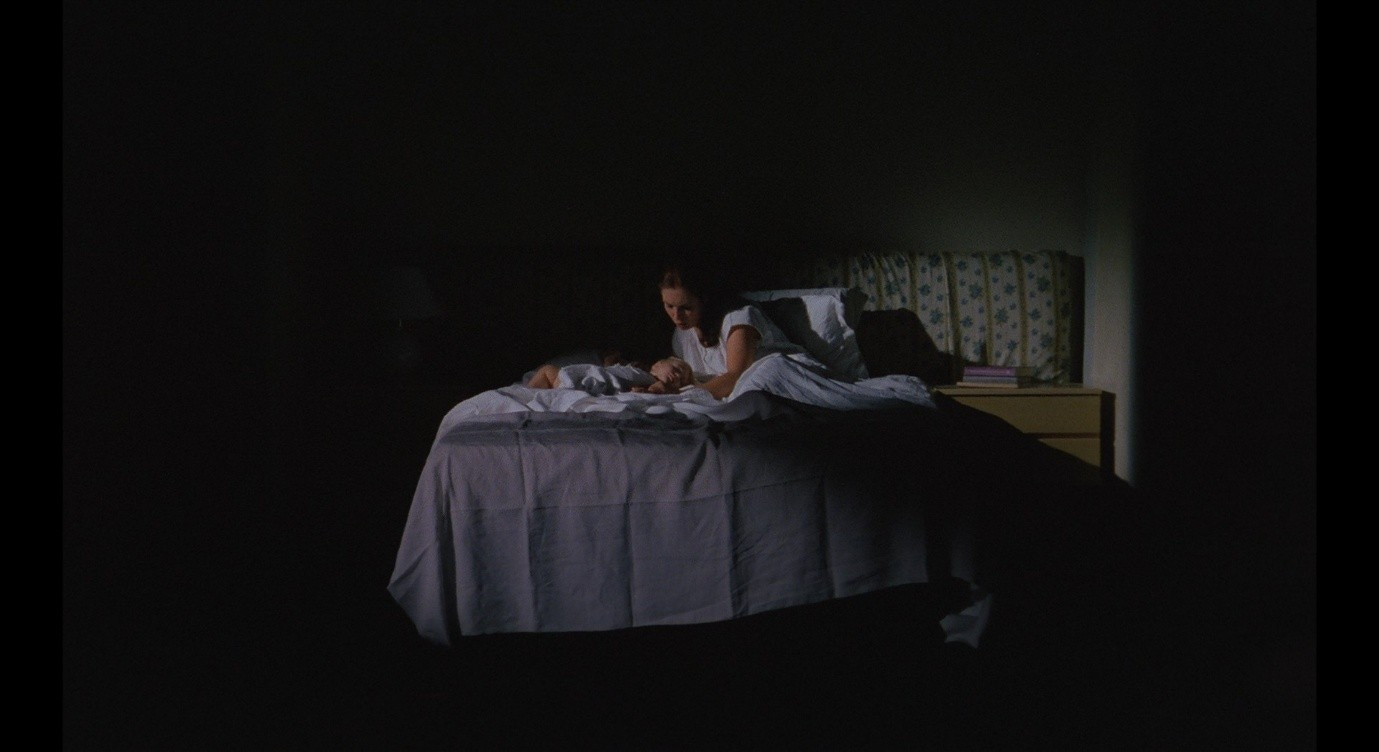

Red Desert has worked hard, up to this point, to establish an association between Valerio and the toy robot in his bedroom. At the start of the film, we saw Valerio moving robotically outside the factory, and shortly afterwards we were introduced to the robot when Giuliana found it patrolling Valerio’s bedroom. Later, the robot dominated the establishing shot of the scene in which Ugo leaves; it formed part of the scientific apparatus that pervaded the apartment, binding Ugo and Valerio together and leaving Giuliana out in the cold. At the climax of the ‘paralysis’ sequence, the robot is again positioned near Valerio’s bed. It stands in a shadow that does not quite extend to its head, leaving the head illuminated; the robot looks protectively towards its master.

The paralysis symptoms make Valerio immobile, like the robot, and his main tactic for ‘selling’ this trick is to be as inanimate and unresponsive as possible. Twice in this sequence, during the initial examination and when Giuliana finds him back on his feet, Valerio pointedly lowers his arms to his sides, echoing the posture of the robot that stands against the wall behind him. In the latter instance, he even faces in the same direction as the robot.

Like Robert Bresson’s ‘models’ – non-professional actors trained to move automatically and inexpressively – the robot-like Valerio is a kind of blank slate onto which emotions and ideas can be projected. If he were really ill, his inanimate behaviour could be both evidence of encroaching paralysis and a response to trauma, a way of repressing or compartmentalising his distress. With hindsight, his inanimate behaviour can be interpreted as the easiest way of fooling people: the less he talks and the less he emotes, the less likely he is to appear inauthentic or be caught out in a lie. When he is finally caught out by his mother, his sudden stillness and silence could be both an impulsive return to the paralysis-act – a last-ditch attempt to ‘sell’ the lie – and an expression of shame and embarrassment.

Beyond these common-sense interpretations, Valerio’s inscrutable behaviour can also be seen as a way of shutting his mother out, much as he did earlier when playing with his chemistry set. In that scene, Giuliana seemed unable to share the connection Valerio had with Ugo, or to join in with the games they were playing. When Valerio demonstrated that ‘one plus one is one,’ he seemed to be taunting her both with the unity between him and his father and with her own solitary state – oneness can mean unity or solitude. Now, with the father absent, Valerio is again confronting his mother with the fact that despite being ‘with him,’ he is not really there and she is alone. Crucially, Giuliana will interpret her son’s ruse as a declaration of self-sufficiency: ‘He’s fine, he doesn’t need me,’ she tells Corrado in the next scene. In this reading, Valerio feigns sickness not only to get out of school but also to get out of spending time with his mother. She finds out he was faking when she looks into his room and sees him playing on his own, without her. This is how he really wants to spend his time.

Angela Dalle Vacche suggests that Valerio’s paralysis ‘can be read as a psychosomatic response to an excess of technology,’ thematically connected to the emotional repression of the adult characters.1 We might put a more positive spin on this by seeing the technology surrounding Valerio as ‘sufficient’ rather than ‘excessive,’ so sufficient in fact that it supplies all his needs and renders his mother unnecessary. When Robert Benayoun suggested that Valerio’s ruse was motivated by a desire to have mechanical legs, Antonioni replied:

Exactly! He wants to resemble his father who is, of course, a kind of robot, like the toys he buys and sets in motion [fait marcher] for his son.2

However, Benayoun also suggests that Antonioni may have been inspired by Bruno Bettelheim’s case-study of ‘Joey the Mechanical Boy.’3 Bettelheim and his colleagues were struck by this ‘at once fragile-looking and imperious nine-year-old,’ by his ‘extreme infantile fragility, so strangely coupled with megalomaniacal superiority,’ which does sound a little like Valerio.4 Joey, in Bettelheim’s diagnosis, was driven to behave like a machine by his loveless, emotionally repressed childhood: ‘He wanted to be rid of his unbearable humanity, to become completely automatic.’5 Perhaps Giuliana is wrong when she says that Valerio does not need her – perhaps his paralysis is a way of insulating himself from whatever is broken in the attachment between him and his mother.

In this sequence, we see Valerio making endless demands on his mother, as though he wants something from her that she is not giving him. Indeed, the most obvious consequence of Valerio’s paralysis is that Giuliana pays more attention to him, not less. She caresses him, fusses over him, tells him every bedtime story she can think of, and draws on the chalkboard when he tells her to. Even before we find out that he is not really sick, the sequence seems to portray Valerio as a slightly cruel tyrant. There is something unkind about his refusal to communicate, about his complaints (‘I’m bored of this game!’), and about his peremptory commands (‘Draw me a new picture! Why don’t you tell me a story?’). Giuliana is so anxious when she frets about the doctor, and looks so tired and run-down when she spends time with Valerio, that it is hard not to feel sorry for her and irritated by him, as most people would have been by Joey and his needy ‘preventions.’6

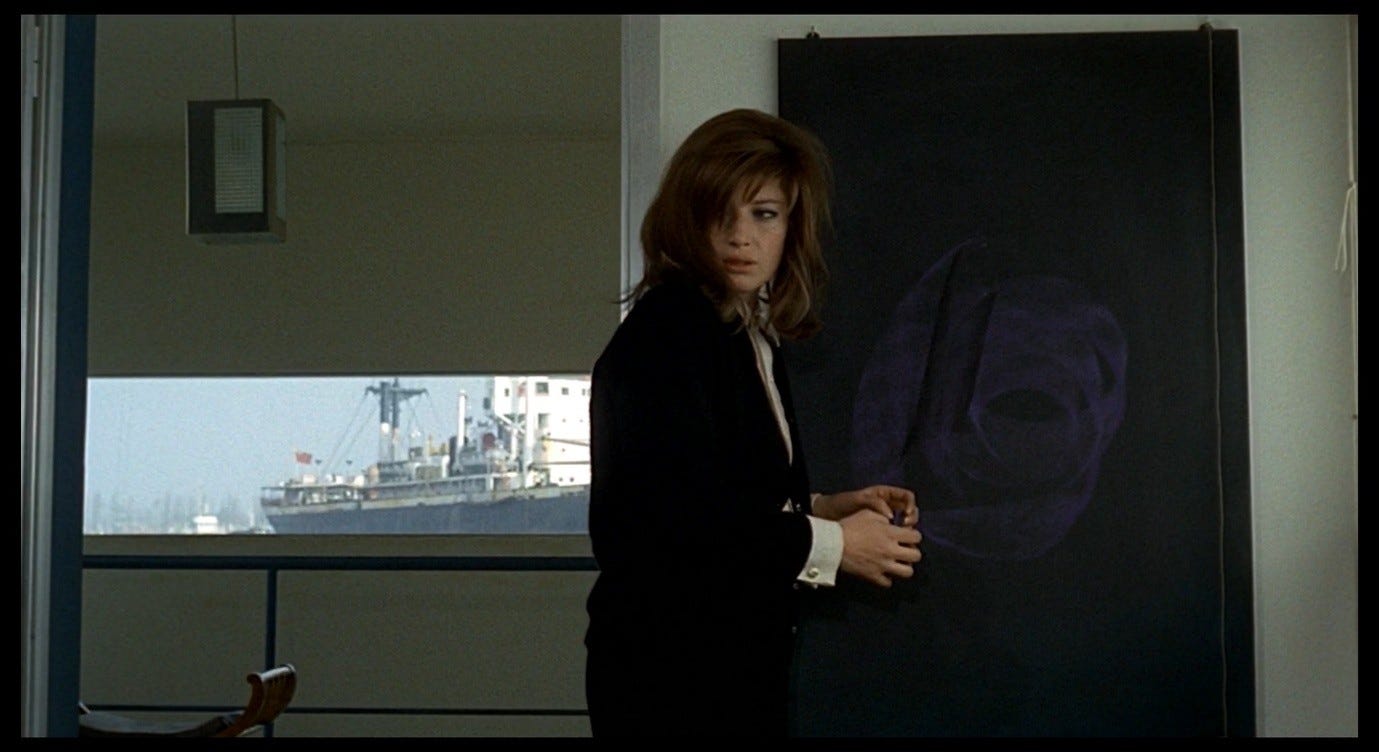

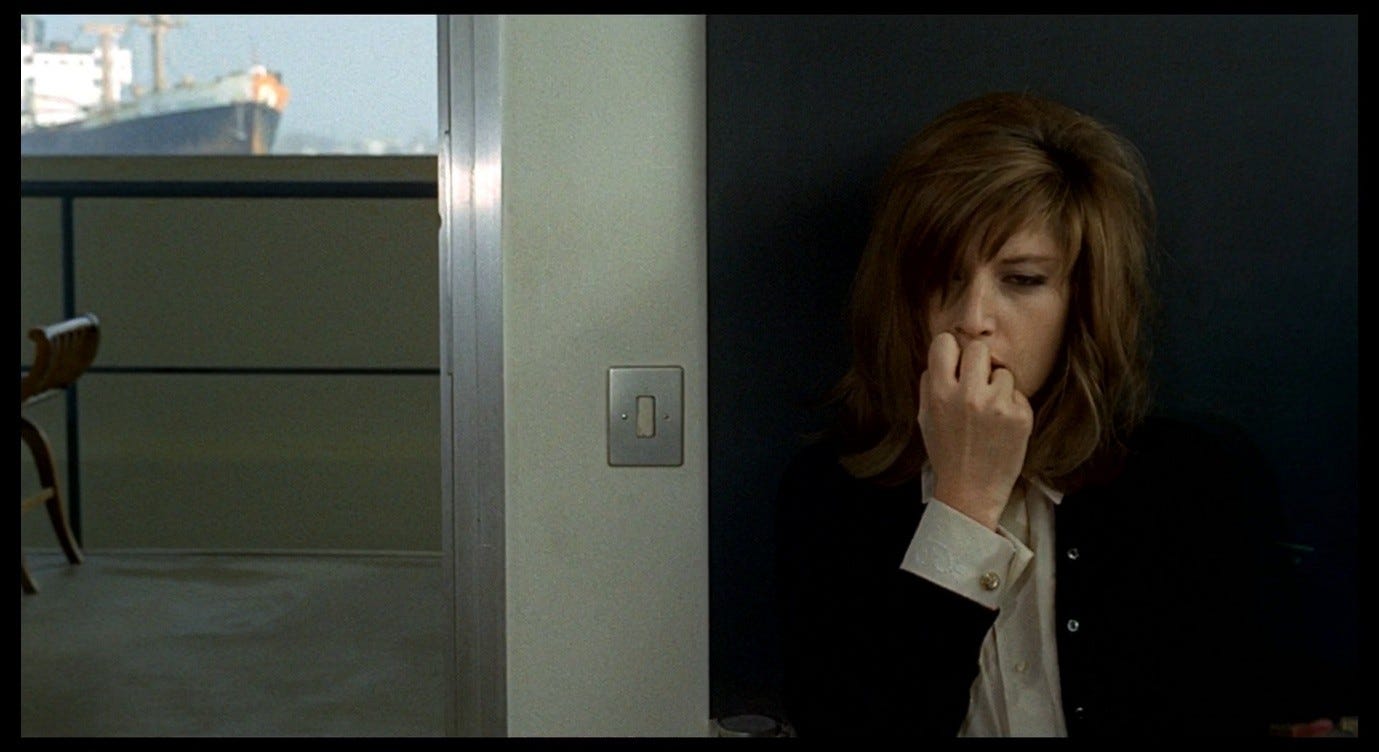

But there is arguably something ‘shut off’ and absent about Giuliana herself in this scene. She leans against the wall of Valerio’s bedroom, biting her fingers, and he interrupts her reverie to demand attention.

When she then stands up to draw on the chalkboard, the screenplay describes her as moving ‘like a robot [come un automa],’7 and after she tells the story of the pink beach we see her staring absently out of a window.

As in the film’s opening scene, when Giuliana left Valerio alone so she could eat her sandwich beside the slag-heap, we can either read her as trying to escape from her creepy robot-child who does not need her, or as being oblivious to Valerio’s needs.

The film tends to emphasise the former perspective, and in so doing it often subverts the conventional tropes of stories like this. In a ‘normal’ film from this time, we might expect Giuliana to feel guilty about being an inadequate mother, about being too wrapped up in her own problems to notice what her son is going through; and in the present sequence, we might expect her to think that Valerio’s illness is a karmic punishment for her near-adulterous relationship with Corrado, as when Laura’s child is injured in Brief Encounter.

One of the many things that makes Red Desert a great film is that it conspicuously fails to invoke these ‘guilty mother’ tropes, instead maintaining its focus on Giuliana’s condition and framing that condition as an adverse response to conventions (both societal and narrative).

However, the film also leaves a space open for us to look at the ‘paralysis’ sequence from Valerio’s point of view. His implicit commentary on the concept of ‘oneness’ in the earlier scene is reminiscent of Marguerite’s challenging of ‘unity and infinity’ in The Sleepwalkers (see Part 32). Like the child wandering into oblivion, Valerio may be coming to terms with alienation and loneliness, indeed with some of the same environmental conditions that his mother is responding to. His father is an industrialist fixated on machines and equipment, so the boy’s bedroom is filled with such equipment. We can see the gyroscope toy on his bedside shelf, and there is literally nothing for Valerio to play with that does not contribute to his STEM-focused education.

Meanwhile, his mother is having an inexplicable breakdown that seems to be related to this industrial environment. She is scared of machines, disturbed by the chemistry set, incapable of joining in with Valerio’s and Ugo’s games. She veers between anxiously tending to her son and retreating into a robotic state of depressed exhaustion.

With his paralysis-act, it is as if Valerio were playing the roles of his father and mother simultaneously. He is completely preoccupied with the machines and robots, to the point of becoming one himself, mirroring Ugo’s treatment of Giuliana by treating her coldly and sternly. He is also parodying his mother’s depressive paralysis, closing himself off to her just as she has closed herself off to him. He seems to be saying to her: ‘This is what you’re like – inscrutable, inert, useless, making everybody worry about you even though you’re not really ill.’ This attitude dovetails with his criticisms of her bedside conduct: she isn’t looking after him, the game is boring, why hasn’t she drawn a new picture, why isn’t she telling him a story? She is both a needy, draining patient and an over-solicitous, incompetent nurse.

Like Samuel in The Babadook, Valerio is ‘misbehaving’ so as to articulate and engage with (in part by mirroring) the adult problems he is gradually becoming aware of.

Valerio’s home and family are supposed to operate in a certain way, but they are afflicted by that hard-to-define sense of alienation that Broch describes in The Sleepwalkers, where the very connections between things (a son’s resemblance to his father, for instance) come to signify disconnection. Like the child who engages in idle play because they are ‘surprised and mastered by loneliness,’ Valerio deliberately isolates himself, ‘concentrating’ his loneliness by aping the machine-like inertia he sees in his parents. As Broch might have put it, this child refuses to succumb to the eclipsing, de-humanising forces of the world he lives in, but at the same time he cannot help but succumb to them, and so flings himself into them as though flinging away his own loneliness.

As I said above, Valerio’s treatment of his mother seems cruel and tyrannical at times, but it is the cruelty of a child who is reacting (or not reacting) to something traumatic in his circumstances. We might compare Valerio to Cecilia in The Night of the Shooting Stars, who focuses on her own selfish needs while those around her are trying to survive the war. As the adults anxiously wait for the bombs to go off, Cecilia smiles and thinks to herself, ‘Let the houses blow up, I’ve never had so much fun.’

Later, in the midst of a savage gunfight, Cecilia puts her hands to her ears and recites a nursery rhyme to ward off danger. The rhyme appears not only to save her life, but also to transform the surrounding violence into a comic-mythological fantasy in which evil is easily defeated by the overwhelming strength of armour-clad heroes.

In this film, what may sometimes appear as ‘selfishness’ is also a good omen about post-war life: perhaps Cecilia, having (to some extent) protected herself from the trauma and loss occurring in front of her, will be well equipped to face the future. And yet there is a troubling sense that, in spite of Cecilia’s seeming imperviousness, the trauma is still seeping through to her, causing a more slow-acting kind of damage. In the final moments of the film, we see her as an adult, recounting her war stories to a baby who cannot hear them. Cecilia looks deeply troubled, burdened by those memories which she, as an adult, now has to face in their unadulterated form. She recites the protective nursery rhyme to her baby in a tone of desperation, while the camera dollies back and shows mother and daughter cocooned in a fragile-looking pool of light, surrounded and made small by an ever-growing darkness.

The Night of the Shooting Stars seems to ask not only what impact the war itself may have had on Cecilia, but also what new traumas the next generation might have to be protected from (or be in denial about). Rossellini asked similar questions through his portrayal of Edmund, the protagonist of Germany, Year Zero. This film’s take on post-war life resembles the ‘absolute zero’ that Broch described, that moment when one set of values disintegrates to make way for another, creating a sense of traumatic emptiness and alienation. Edmund spectates the problems of adults who dismiss him, and he struggles to know how to respond. He has a duty to love and support his family, but the lingering tenets of Nazi ideology (among other influences) prompt him to fulfil this duty by murdering his own father. Acting according to that machine-like ‘singleness of purpose’ that defines the world of The Sleepwalkers, Edmund realises that the weak must be destroyed to make way for the strong, and poisons his ailing father’s tea. Every time his father gulps down the tea, Edmund gulps too, as though he were poisoning both his father and himself.

The conflicts between the different values he is trying to live up to – the bonds with his family and the ruthless pragmatism of his age – place him in an untenable situation, and like Marguerite he eventually flings himself into the void.

Edmund’s suicidal leap at the end of the film expresses the loneliness that has enfolded him: filial duty makes him want to atone for murdering his father, but he is also disconnected from his family and from society in general, both by his crime and by the circumstances that prompted it. His trajectory in the film embodies that sense of ‘unity challenging infinity, and infinity challenging unity’ that we saw in Marguerite’s final journey. Edmund is isolated because of his circumstances, but he is also an embodiment of those circumstances; he is both cast out of ‘Germany’ and an all-encompassing symbol of ‘Germany’ in this moment.

Unlike Cecilia and Edmund, Valerio is not engaging with a wartime or post-war context, but with the high-point of the economic boom that followed. His loneliness and callousness are, therefore, of a different sort. He does not simply retreat into his own world, nor does he try to force a solution to problems he cannot understand. Instead, he performs a trick that encapsulates both the supreme efficiency and profound sickness of the world in which he lives. In a sense, he turns himself into a ‘sick robot,’ someone who is both stricken with paralysis and an enhanced version of his previous self.

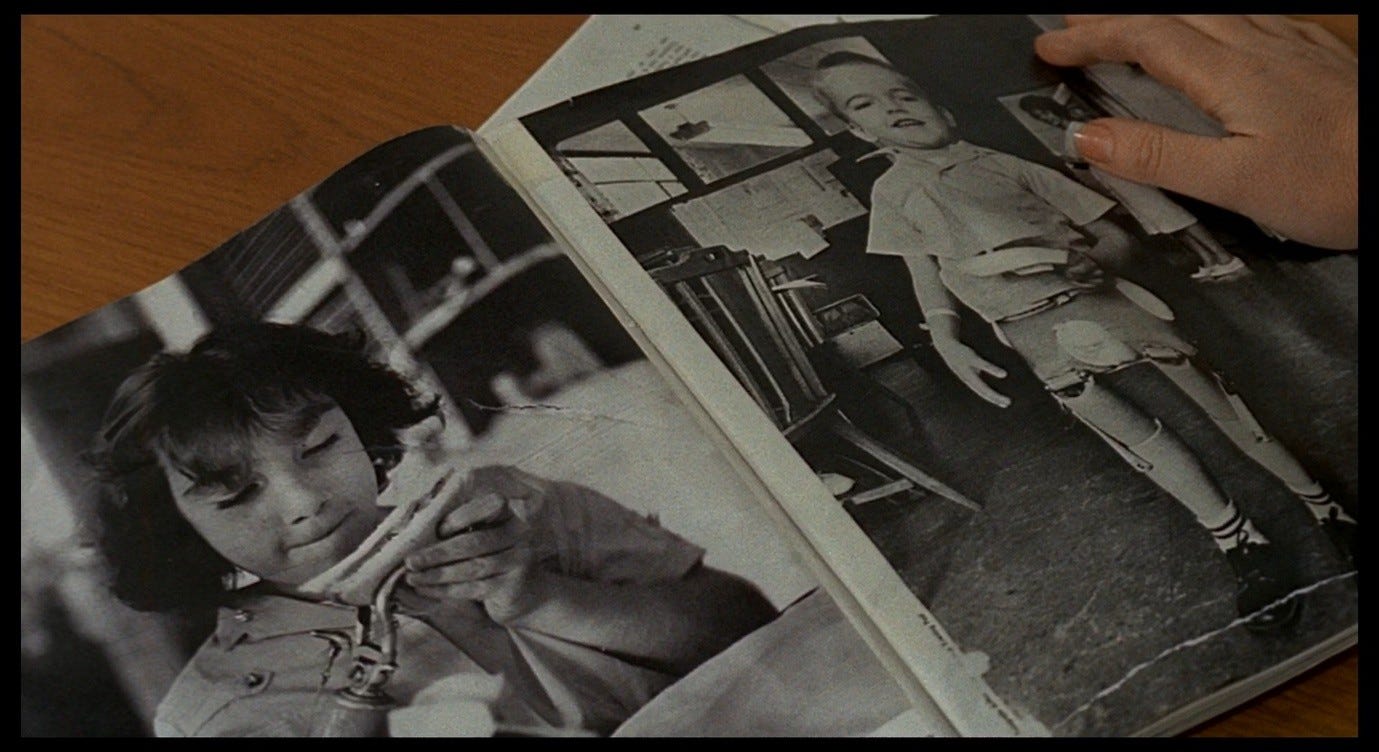

When Linda glances through the magazines Giuliana has been reading, she sees images of children with prosthetic limbs. These photographs must have been fuelling Giuliana’s anxiety, but the children are all smiling happily and holding objects (toys, food) with apparent aptitude. In the context of Red Desert’s commentary on the increasing mechanisation and robot-isation of society, the images are suggestive of ‘new, improved children’ rather than of disability (despite an alarming headline about thalidomide). Indeed, in one photograph it is impossible to tell whether the figure with its back to us is a real child or a life-sized doll made entirely out of prosthetics.

Giuliana pokes Valerio’s legs, asking him whether he feels pain, and he repeatedly answers ‘No.’ His is a fantasy, not of immobility, but of being a machine that cannot be hurt and that is oblivious to the pain of other people.

He can manipulate his mother’s feelings through play-acting, get out of going to school, and spend the day playing with the other machines in his bedroom, with Edmund’s ruthlessness (the weak must make way for the strong) and Cecilia’s lack of shame (he has never had so much fun). It is a brilliant trick, but also a painfully lonely one. Perhaps its closest analogue is in Cría Cuervos, in which the orphaned Ana imagines that she has murdered her pig of a father and that she can conjure her loving mother through force of will, but ultimately has to come to terms with her utter powerlessness in this world run by dysfunctional adults. ‘You will forget me, you will forget me,’ says the refrain in the pop song (about a departed lover) that Ana compulsively listens to. The child is supposed to forget her dead mother, but for Ana it is as though her mother, by being dead, were forgetting her. All Ana’s fantasies and schemes are responses to the condition of abandonment and emotional neglect in which she finds herself.

Unlike Edmund, she does not have access to real poison – only bicarbonate of soda – and for all the vividness of her daydreams, her mother is irretrievably gone. As in The Night of the Shooting Stars, this story is narrated by the adult version of the child protagonist, in this case played by the same actor (Geraldine Chaplin) who plays Ana’s mother. This grown-up Ana reflects ruefully on a common misapprehension about childhood:

I can’t understand people who say that childhood is the happiest time of one’s life. It certainly wasn’t for me. Maybe that’s why I don’t believe in a childlike paradise or that children are innocent or good by nature. I remember my childhood as an interminably long and sad time, filled with fear. Fear of the unknown. There are things I can’t forget. It’s unbelievable how powerful memories can be.

‘Children are happy,’ said Katherine in Journey to Italy, framing her adult misery as a loss of childlike innocence. But this is one of several false notes in that film’s ending: the happiness of children is something adults project onto them, and what appears as carefree ‘play’ can be just a short step away from murder, suicide, or a nebulous living death.

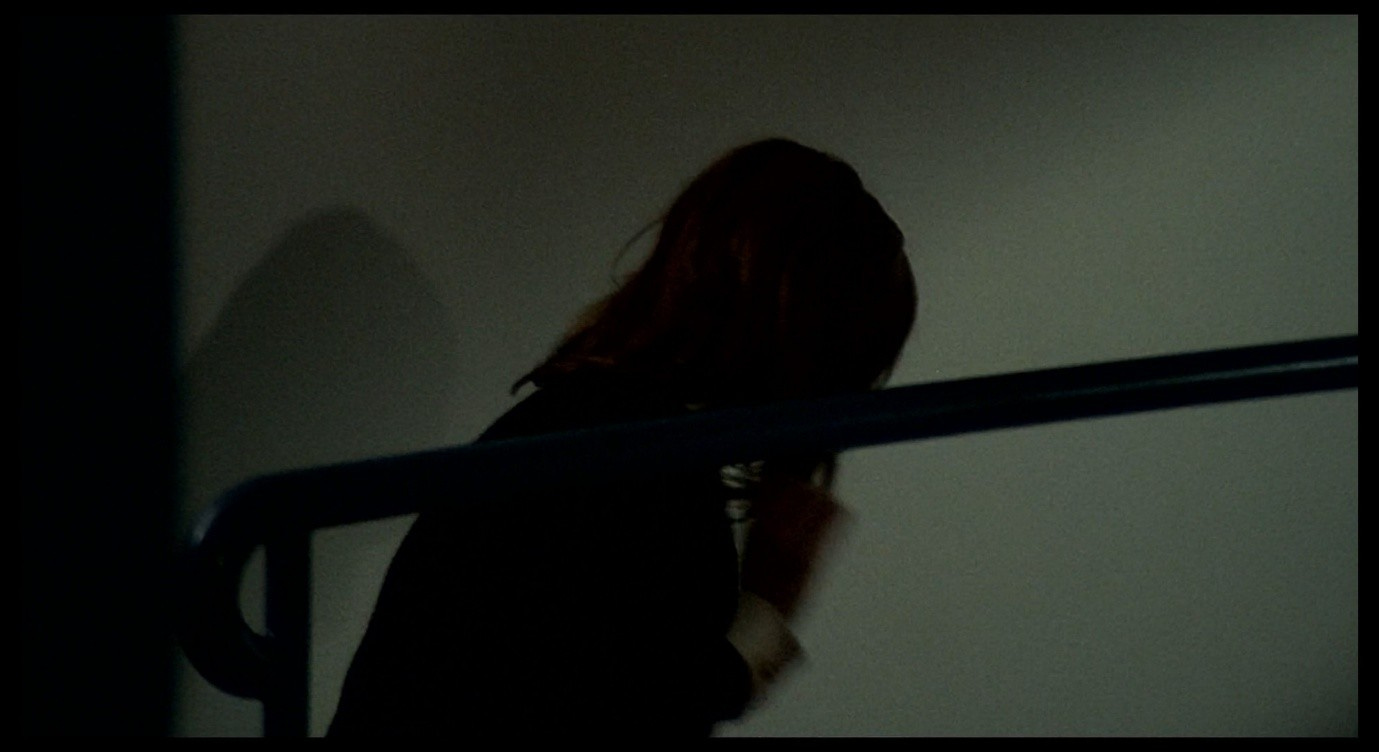

When we (and Giuliana) discover Valerio’s trick, it reveals another layer of the ‘terrible thing in reality’ to which the film is bringing us closer and closer. The discovery is shot like a scene in a horror film. From inside Valerio’s bedroom, we see the half-open doorway framed in a canted angle. We inhabit a sinister, gloomy space, which we are given a moment to register before Giuliana enters the frame. When she stops and stares in the direction of this gloom, it is as though she were looking at something monstrous. Her disturbing chalk-drawing occupies the right-hand side of the frame, out of focus so that it has an uncanny effect like a supernatural mist.

The reverse-shot is bathetically matter-of-fact: here is Valerio, in his well-lit room, grabbing an anatomical model (his mechanical heart and lungs) from the table and taking it back to his bed. Although we have reversed our position, we seem to be stuck in the darkness again – it has followed us to the other side of the doorway. In a mirroring of the previous shot, we have a moment to appreciate our place in this darkness after Valerio has left the frame, and a moment to process the revelation Giuliana herself will have a few seconds later.

When she enters the room and embraces Valerio (who has paused in a half-kneeling position on the bed), she begins by checking his legs to ensure they really are okay, then breaks into a paroxysm of joy and kisses him frantically.

Her transition from this state into a dawning realisation of what has happened is another subversive play on a familiar trope. In most films, when a parent learns that their child is ‘safe after all,’ they first express relief and adoration for their ‘saved’ offspring, then seamlessly shift gear into angry rebukes along the lines of ‘Don’t you ever scare me like that again.’ For Giuliana and Valerio, the situation is different. While his mother showers him with kisses, Valerio pointedly looks away from her, and she herself does not look him in the eye. As in the ‘one plus one’ scene, Giuliana embraces her child but stares past him. There is something here that she does not want to see, something that will almost destroy her, and when she finally pulls back and looks at Valerio’s face, her joy disintegrates instantly. As he continues to look away from her, she asks, ‘But then...why did you tell me...?’, without finishing the sentence.

In L’avventura, when Anna is newly reunited with Sandro and he asks how she has been, she says ‘Awful [Male],’ and he asks ‘Why?’ She then angrily repeats the word ‘why’ while hitting Sandro, and although he laughs in response, there is something about this ‘why’ that cuts to the heart of the problem between them – the problem she sums up later when she says that she no longer ‘feels’ Sandro.

The Italian word perché – literally ‘for what’ – underlines the fact that this is a question about a relationship: for what, or for whom, has Anna been suffering all this time? For Sandro? She hits him as though expecting him to vanish beneath her fists, as though she were saying, ‘Exactly, perché, what have I been missing and what have I come back to?’ Giuliana’s ‘why’ in Red Desert is quietly devastating in a similar way. Just as Anna’s misery (in Sandro’s absence) does not quite indicate that she missed him, so Valerio’s feigned illness (which keeps him at home with his mother) does not quite indicate a desire to spend time with his mother. For what, or for whom, does Valerio care, if not for his mother? In both cases, the ‘why’ opens up a chasm between the two characters. Anna feels awful because she has no connection with Sandro; Valerio’s trick exposes the lack of any bond between him and Giuliana.

There is no trace of anger in Giuliana’s reaction. Instead, she seems to perceive this trick as an incomprehensibly hurtful betrayal. Her ‘Why?’ carries a tone of ‘How could you?’, and she runs away as if her son posed some kind of mortal danger to her.

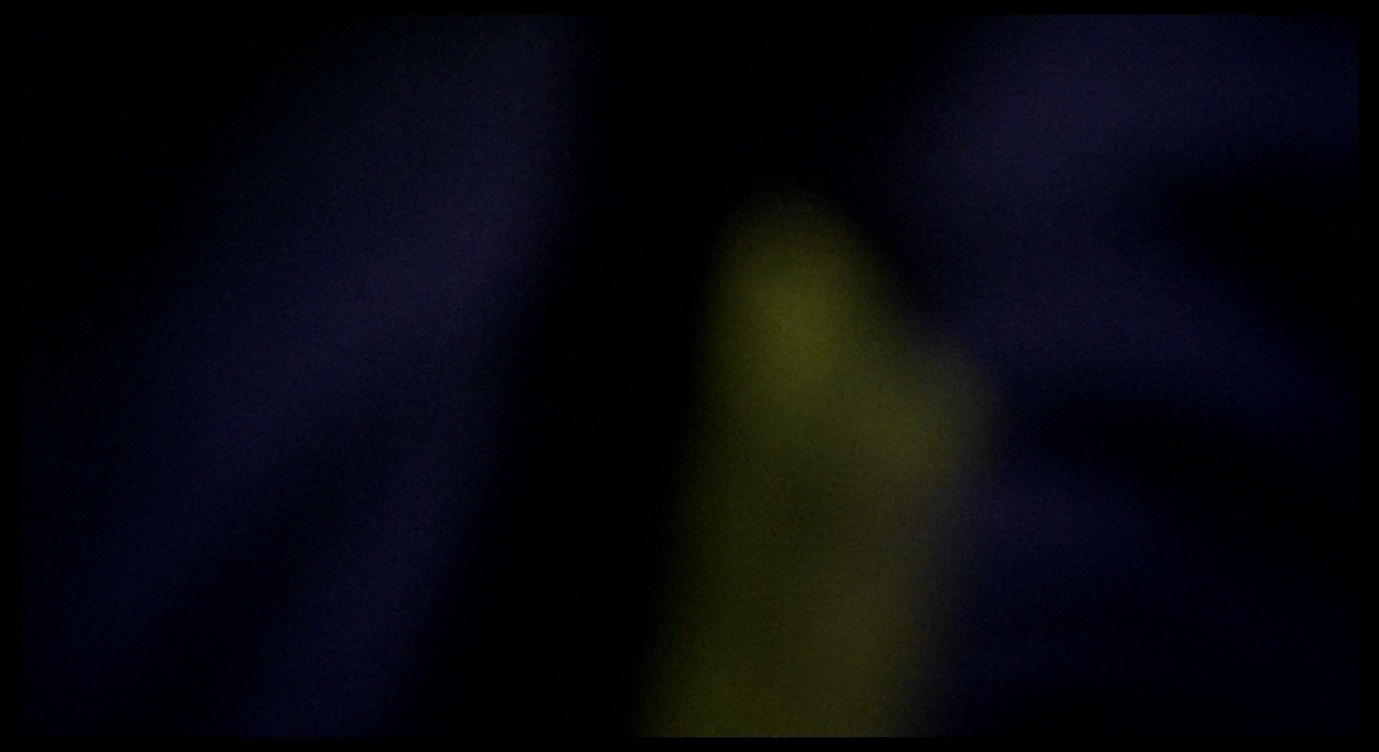

We hear the menacing electronic sounds from the ‘night terrors’ sequence, reminding us of the unidentified horror Giuliana saw when she looked into the darkness of the lower floor (see Part 10). The camera switches to a long lens that collapses the space in Valerio’s bedroom, making us unsure of where we are or what we are looking at as Giuliana leaves. At the end of the shot, the out-of-focus chalk drawing fills the frame again, linking back to the horror-movie composition of a minute earlier.

Some nameless, shapeless nightmare, partially represented by this colourful blur, has opened up and consumed the image. (We will come back to this colourful blur in Part 39, when it reappears in mutated form on the ceiling of Corrado’s hotel room.)

Giuliana’s frightened reaction might seem excessive, and might seem to place an unreasonable burden of responsibility on Valerio. He should be able to play a childish prank without feeling like he has traumatised his mother. But if we see Valerio’s behaviour in Broch-ian terms, as a prank that stems from and attempts to resolve his own encounter with loneliness, Giuliana’s devastation seems appropriate. She was similarly upset by the denial of the grido during the sequence in Max’s shack, trivial as that argument seemed to the other characters (see Part 20). For Valerio to trick her like this represents a breakdown of the relation between mother and son, or even a mockery of her love and concern for him, that is akin to the breakdown of the relation between reality and perception in that earlier scene. People do not hear what they hear, or might as well not hear it; there is no love between people, or there might as well not be any. In his experimental play-acting and robotic self-transformation, Valerio is grappling with these revelations too, and like his mother he is ultimately left to deal with them on his own.

Next: Part 34, A story for Giuliana.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 54

Benayoun, Robert, ‘Le désert rouge’, Positif 66 (1965), pp. 43-59; p. 59 (my translation)

Benayoun, Robert, ‘Le désert rouge’, Positif 66 (1965), pp. 43-59; p. 45

Bettelheim, Bruno, ‘Joey, a “Mechanical Boy”’, Scientific American 200 (1959), pp. 116-127; p. 117

Bettelheim, Bruno, ‘Joey, a “Mechanical Boy”’, Scientific American 200 (1959), pp. 116-127; p. 117

Bettelheim, Bruno, ‘Joey, a “Mechanical Boy”’, Scientific American 200 (1959), pp. 116-127; p. 119

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 486