Everything That Happens in Red Desert (19)

Industry, exploitation, and 'Sick Eros'

With the arrival of Max, Linda, and Mili, the daytrip pivots from whatever the original plan was, and turns into dinner and flirtation in Max’s shack. Red Desert’s commentary on the impact of industry also pivots: from pollution violating nature, we move onto the exploitative nature of business, and an explicit link is made between this and sexual exploitation.

We should return for a moment to Ugo’s remark, ‘effluent has to end up somewhere,’ and note that this industrial fatalism echoes the erotic fatalism of other Antonioni characters. Sandro in L’avventura shifts his attention from one woman to another according to their proximity, with all the inevitability of waste water travelling through a pipe. His libido has to end up somewhere, and the question of who that ‘somewhere’ is, or how she feels, seems to be of little importance. His engagement to Anna, his terms of endearment to Claudia, and the bundle of money he throws at Gloria (‘a little memento’ as she calls it with ironic sentimentality) – they are perhaps all the same thing.

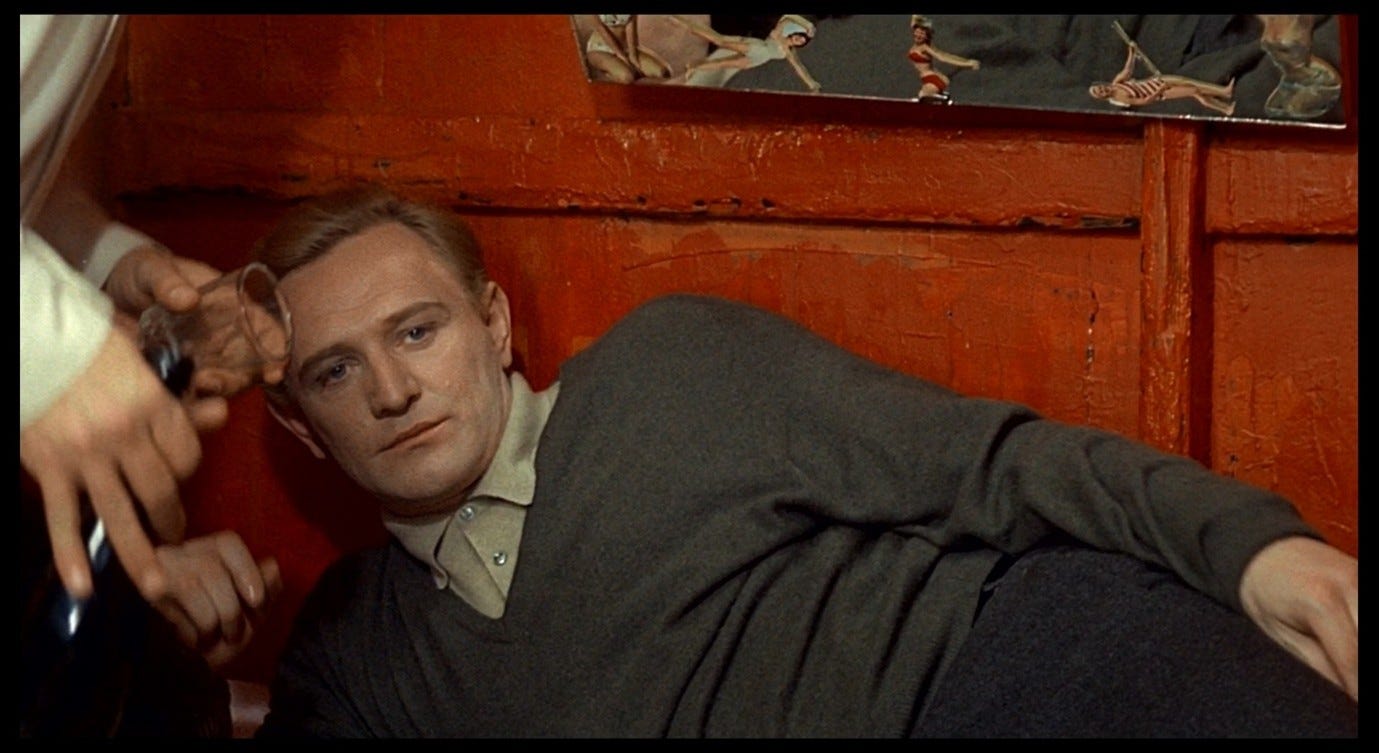

The idea of love as an economic transaction, or an industrial process, is most clearly embodied in Red Desert by Max, whom we meet for the first and only time in the daytrip sequence. He is a more senior and successful industrialist than Ugo or Corrado, and from the moment of his introduction he is figured as having the upper hand over them. He knew this would be an unsuitable place for their outing, so has already had dinner prepared at his own fishing hut.

As it turns out, Max’s hut is equipped for more than just fishing and eating. A large bed is built into a red-painted alcove, with a mirror on one wall which, as the screenplay comments, ‘clearly shows the purpose for which [the bed] is intended.’1 Max evidently wants to get an orgy going. He serves quails’ eggs and initiates the conversation about aphrodisiacs, he gropes and flirts with Mili (in the presence of his wife, Linda), and when the firewood runs out it is hard not to suspect that this was a deliberate ploy to encourage warmth-inducing physical intimacy among his guests.

Mili’s assigned role at this party is to behave in a highly sexualised manner at every opportunity, and for a while we learn literally nothing else about her. She is introduced as a languorous pair of feet warming themselves by a stove, recalling the image of Gloria clutching at the money with her feet in L’avventura.

Mili reveals a similarly economic view of sex when she explains that she dumped her former boyfriend because she cannot sleep with someone who earns less money than she does. Mili plays an erotic game with Corrado and Max, she encourages the men to be less euphemistic in the discussion of aphrodisiacs (‘Where do they smear it?’), and she says that if she cannot have sex she would at least like to be talking about it. Linda repeatedly rebukes or makes fun of Mili, telling her that even without aphrodisiacs she always has ‘bedroom eyes,’ and at one point calling her a ‘porcona’ (a derogatory term meaning something like ‘old slag’ or ‘whore’). Everyone laughs at these comments. It seems that the lightly antagonistic relationship between Max’s wife and mistress is an accepted, indeed decorous element in this social group: these are the roles these women have been given.

Then, after a particularly sleazy comment from Max, Mili has the following exchange with Linda:

MILI: I hate him.

LINDA: Who?

MILI: Your husband. Because he’s always there, like a crow. Always ready to swoop down on a bankrupt factory or a woman in crisis. You’ll see! You’ll see, he’ll end up having his way with me too.

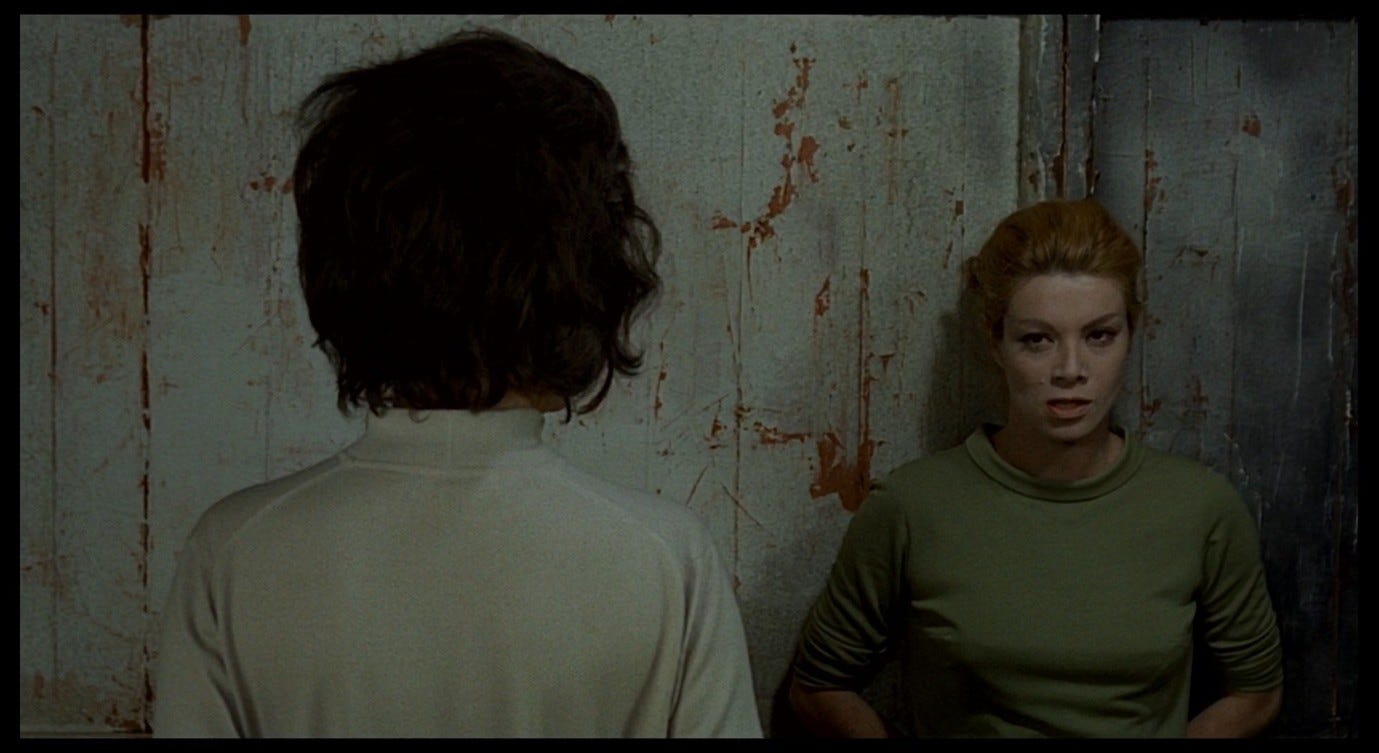

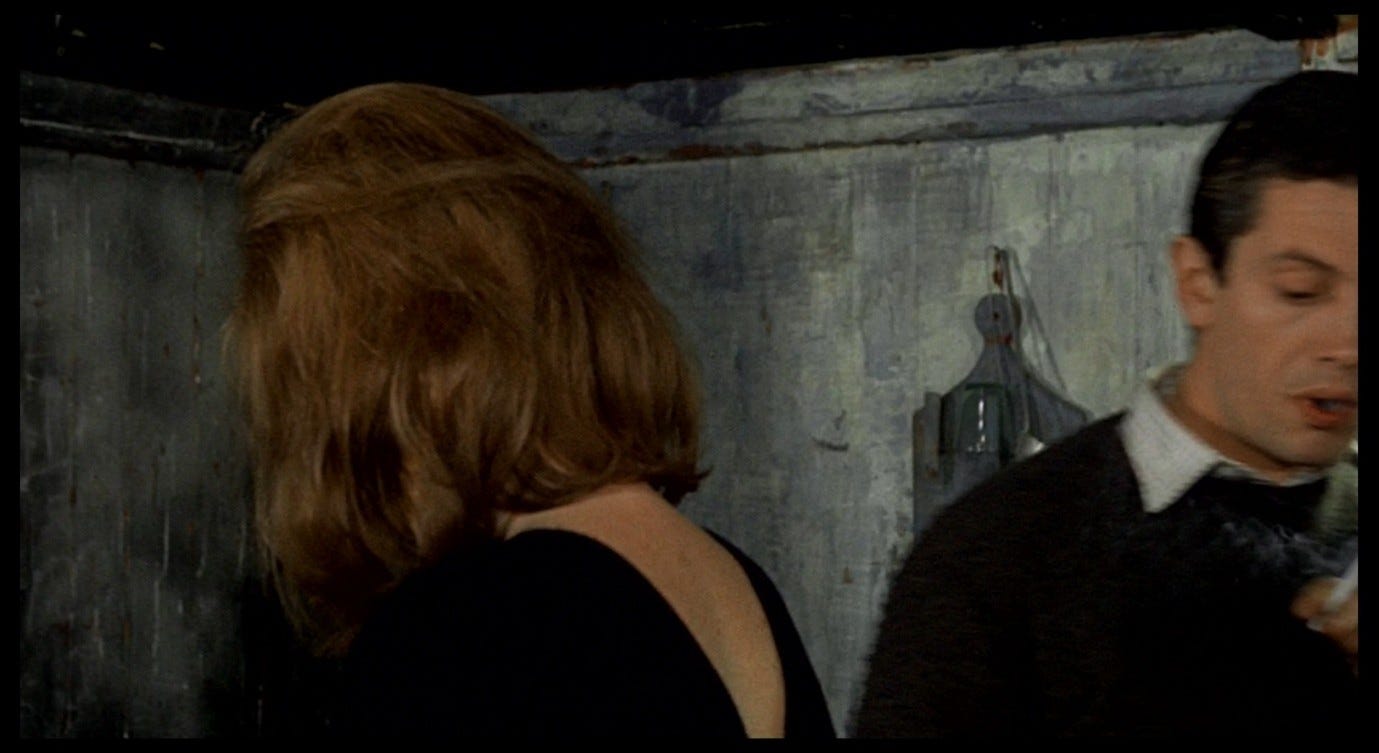

The screenplay specifies that Giuliana can hear all this, and that she is visibly shocked. In the film, however, we do not see Giuliana’s face. She is sitting in front of the stove when Mili goes over to Linda, but she is pushed out of the frame by the camera movement.

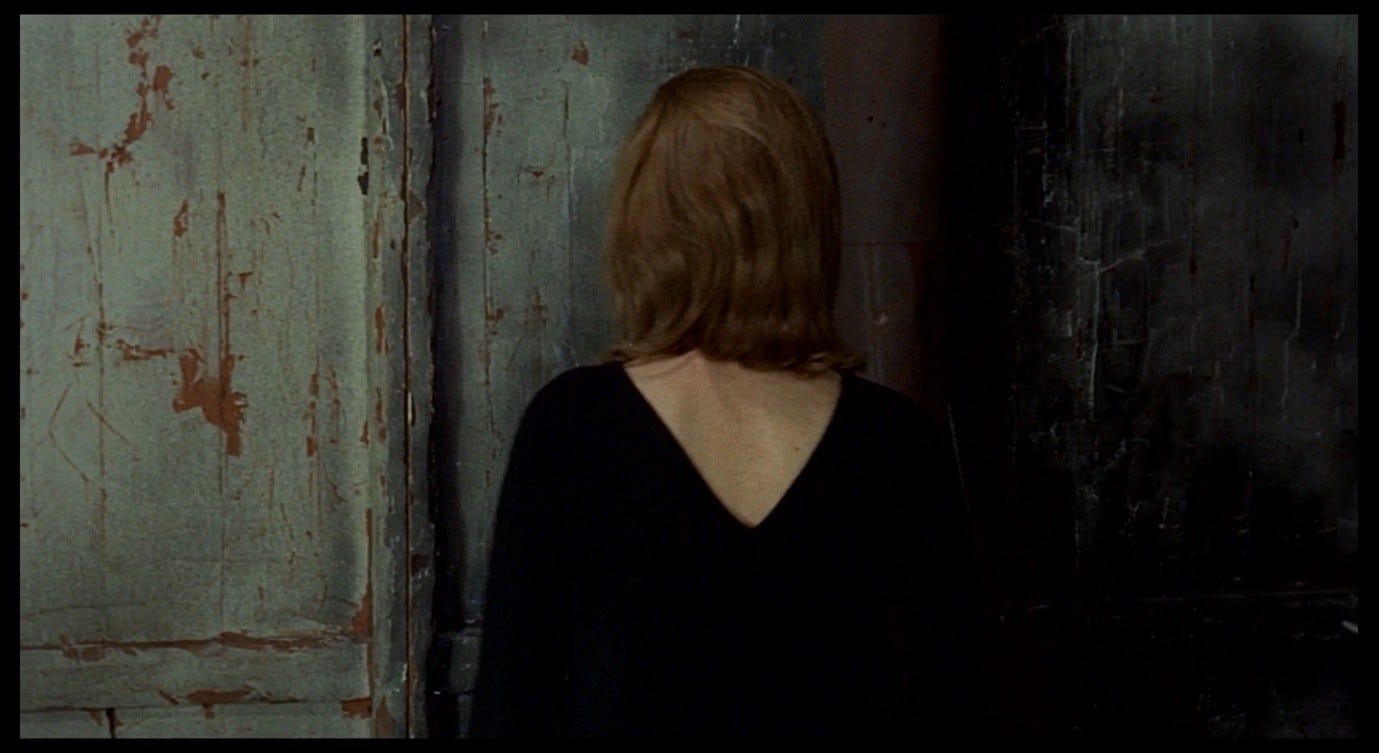

During Mili’s outburst, Linda turns away dismissively, and Mili exclaims ‘You’ll see!’ to get her attention – at this moment, Giuliana stands up and re-enters the frame, with her back facing the camera.

After Mili finishes speaking, we cut to a lower angle from Giuliana’s left – still leaving her face invisible – and see Ugo light a cigarette and glance at Giuliana before walking out of shot.

We then cut back to the previous angle, but with the camera moved to the right so that Giuliana (still with her back to us) is in the centre of the frame. Mili walks away, leaving Giuliana alone. Giuliana sits back down in the chair and looks into the stove, placing herself in the same position she was in a minute ago…and the same position Mili was in when this sequence began.

With this in mind, let’s look again at how this scene begins: after warming her feet by the fire, Mili sits back in the chair; we cut on this action to Giuliana turning from the window, subtly suggesting a link between these two characters. This is how the film establishes the interior of the shack, before cutting to a wide-angle establishing shot. Somehow it is more of a priority to introduce Mili and Giuliana (one looking into a fire, one looking into the sea) than to give us a clear sense of the space they inhabit.

Mili, Linda, and Max have only just been introduced, and out of these three only Linda will reappear (very briefly) in a later scene, so these characters are not especially important in their own right. Mili’s predicament serves as a counterpoint to Giuliana’s. Something about Mili’s words resonates with her, and the film invites us to reflect on this precisely by not showing us Giuliana’s face, by not having her verbalise her thoughts. Whatever she is feeling and thinking, it cannot easily be expressed. The film also de-humanises Giuliana in this moment by reducing her to a head of red hair, which is thematically appropriate given that Mili is talking about her own de-humanisation. Peter Brunette, commenting on the frequent ‘back shots’ in Antonioni’s films, argues that in some cases

the turning of the woman’s back seems […] like a subtle sign of resistance to the penetrating male gaze of the director and his stand-in, the camera, a resistance that Antonioni is explicitly thematizing.2

In the current context, there is a mixture of resistance and vulnerability in Giuliana’s turning-away. The camera’s ‘penetrating male gaze’ cannot intrude on her emotions in this moment, but this moment is also about her/Mili’s sense of powerlessness in the face of that male gaze.

For a man of the world like Max, women and factories, business and erotic affairs, are essentially the same thing. His dominance in both spheres is inevitable: he always gets his way. He brags to Corrado about his canny business decisions. His motto is, ‘Buy and sell quickly, go, go!’, and he never goes looking for opportunities but always lets them come to him. When Max shares this pearl of wisdom with Corrado, the latter has just moved away from Giuliana and Ugo to give them some privacy, with a resentful and defeated look on his face.

The advice clearly refers not only to Corrado’s irritating shop-talk (at a time when he should not be chasing business opportunities), but also to his pursuit of Giuliana. Corrado, Max thinks, would have more success if he simply bided his time and waited for his prey to come to him. This is what Mili means when she says Max is ‘always there, ready to swoop.’ When the factory is at its lowest ebb, or when the woman is at her most vulnerable, he will be waiting for them, and will act with the unerring instinct of a predator.

Mili resents the hyper-sexualised role that she plays, but recognises that she is trapped in it and that her fate is inevitable. Giuliana too is playing a role, primarily (in this scene) as Ugo’s wife. Ugo seems to have overheard Mili’s comments. When he glances at Giuliana, lights a cigarette, and walks away, there is a dismissive shrug in this gesture that recalls his comment about the polluted landscape. If Giuliana is horrified by what she has heard, well...what does she expect? Max is like that; men are like that; factories get bought and sold; women like Mili get exploited; women like Linda get cheated on; they have to put up with it and even joke about it; effluent has to end up somewhere.

By highlighting this moment between Ugo and Giuliana, the film draws an association not only between two ‘women in crisis,’ but also between the two men who are in some sense using them. The sequence of shots is spatially disorienting, all the more so because the film does not give us a reaction shot – or a certain kind of reaction shot – when we expect one. Like the camera, Ugo registers Giuliana’s reaction but does not really see or engage with it; but the camera does see his careless response, and this perhaps enables us to understand Giuliana’s feelings, because it contextualises them. In short, we as spectators are left feeling uncertain about our positioning, just as Giuliana is left to reflect uncomfortably on her place in the world.

The bleakness of the sequence in Max’s shack is offset by moments that suggest something more hopeful, a possibility of resisting or liberating oneself from oppressive roles and structures. When the characters gather in the red room, Giuliana’s mood seems to lighten. She enjoys the physical proximity to Corrado and then to Ugo.

There is an informal intimacy to this gathering, a blurring of each individual’s personal space, that aligns with Giuliana’s (allegedly dysfunctional) way of relating to the world – that love for everything-at-once she spoke about a few minutes earlier in Mario’s flat. When she eats the quails’ eggs and declares that she ‘wants to make love,’ the screenplay specifies that she says this with ‘great naturalness [molto naturalezza].’3 The camera matches her circling movement as she stares directly into the lens, creating a strong sense of identification; the camera feels what she feels, we connect with that feeling, the emotions are unmediated. The other characters’ reactions seem equally natural and spontaneous, and they seem to constitute a single unanimous reaction: everyone bursts out laughing, with Giuliana rather than at her, in impulsive delight at her frank, earnest expression of desire. Everyone collapses onto each other, as though a long-held tension had finally been released.

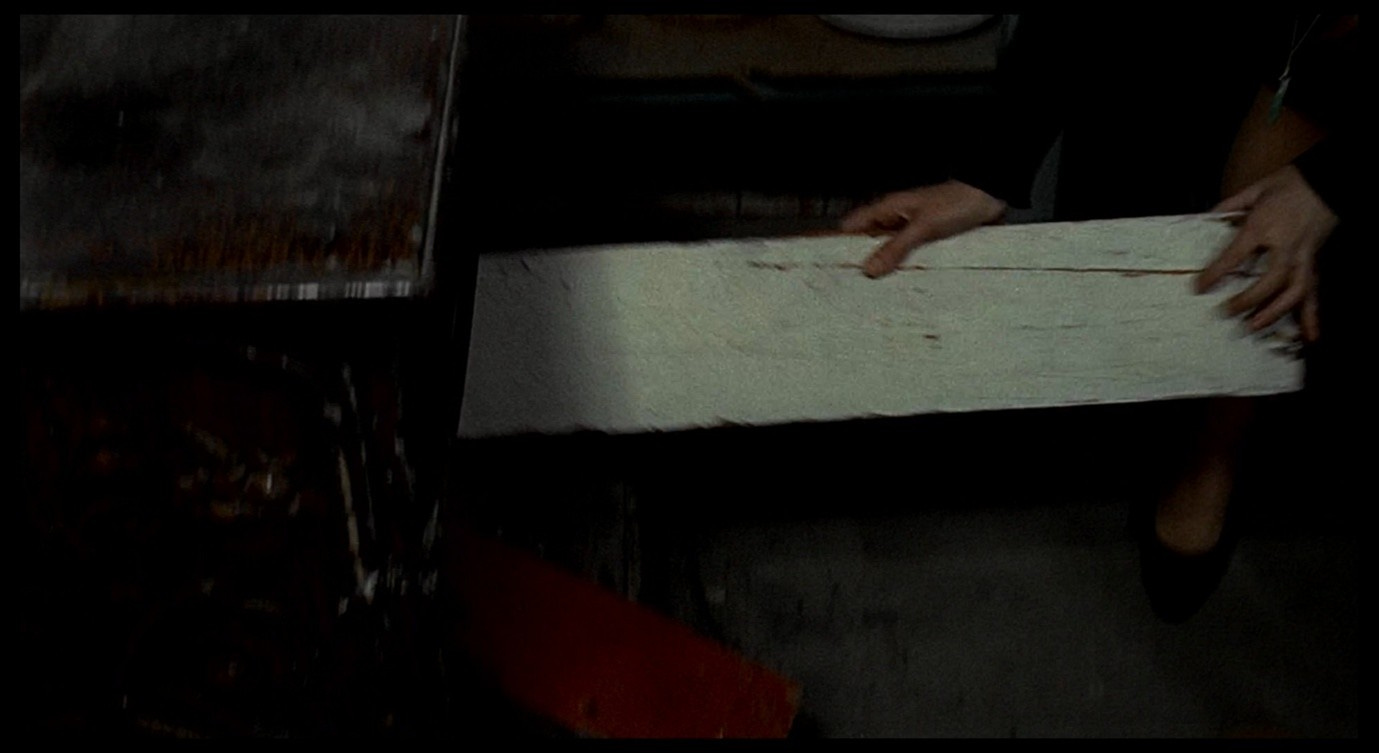

A similar type of hilarity erupts later on, when Mili starts putting the broken planks into the stove, then asks the others to help her tear the shack apart so they can all warm up. If, as I suggested earlier, the absence of firewood is a calculated move on Max’s part, Mili’s actions here are a way of subverting his authority.

He has just bragged about selling this shack to his employee, Orlando, and now he protests against the destruction of this recently sold property: he can faintly be heard saying ‘é per la mora,’ meaning (I think) that Orlando’s payment has been deferred. This damage will reduce the property’s value and necessitate a re-negotiation of the price. As in the red room, the characters’ unfettered joy in the pursuit of sensual pleasure (warmth, in this case) feels like an escape – a fulfilment of the desire for escape that motivated this daytrip in the first place.

However, both these moments of liberation are fatally undermined. Paul Coates sees a dynamic, throughout this sequence, of impulses thwarted and displaced by the rules of decorum:

[T]he wooden slats [are] painted red on one side [and] white on the other. The combination of these two colours seems to frustrate an impulse to action it displaces into substitute action. If red aims at passion, white dampens it. Thus, although the couples crawling into the red-slatted area of the shack grow erotically excited as they do so, and Giuliana mentions how the quail’s eggs she has eaten make her want to make love, nothing happens. The mood of incipient orgy veers away into titillation, and Ugo informs Giuliana with embarrassment that there is no way love can be made in company. Because the social context constrains the impulse promoted by the intimacy of the shack and the colour red, it manifests itself only in displaced form: the inner wall of slats, which looks white from the side from which it is attacked, is broken up – primarily by Corrado, whose desire for Giuliana can only be displaced – and used to feed a fire that translates impulse into the disappointingly metaphorical.4

There is indeed a layer of this sequence which locates the ‘problem’ in the non-fulfilment of desire, especially Giuliana’s. When she tells Ugo that her declaration in the red room (‘I want to make love’) was sincere, and he smiles indulgently then says with a shrug, ‘But how can we?’, the implication seems to be that Giuliana was hoping for an outbreak of love-making.

The sterile environment of her home is where sex is supposed to take place, but there she finds Ugo’s advances oppressive; when she at last finds herself in an environment that promotes intimacy and free expression, her desires have to be stifled. But the problem is more complex than this formulation suggests, because the forms of intimacy and love-making facilitated in Max’s shack are not simply stifled, displaced, or translated into metaphors; if anything, these desires become even more problematic when they are fulfilled.

The spontaneity of the ‘red room’ scene, that sense of free love that we experienced briefly, is undercut by the sense that it is also a kind of ‘opportunity’ to be exploited. The men’s obviously calculated behaviour (repeatedly signalled as such in the screenplay’s stage directions) is in contrast to Giuliana’s naturalezza. Max consistently positions himself so that he can grope Mili, his hand accidentally-on-purpose landing on her breasts when he first climbs into the bed.

Just after Giuliana has said ‘I want to make love’ and the group has exploded with laughter, she notices Max groping Mili again, and turns to Corrado with a look of consternation, as though checking in with him (rather than Ugo, tellingly) to ask what sort of interaction is going on here.

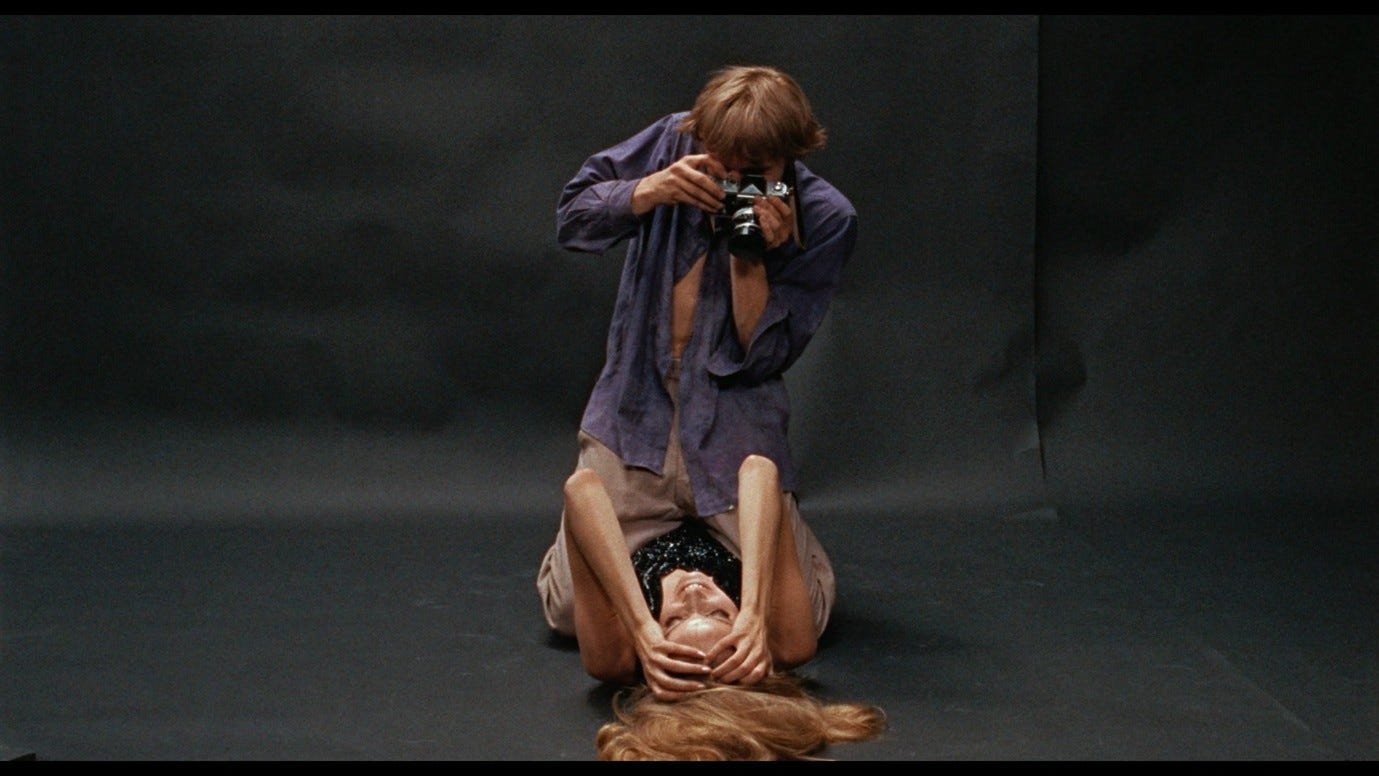

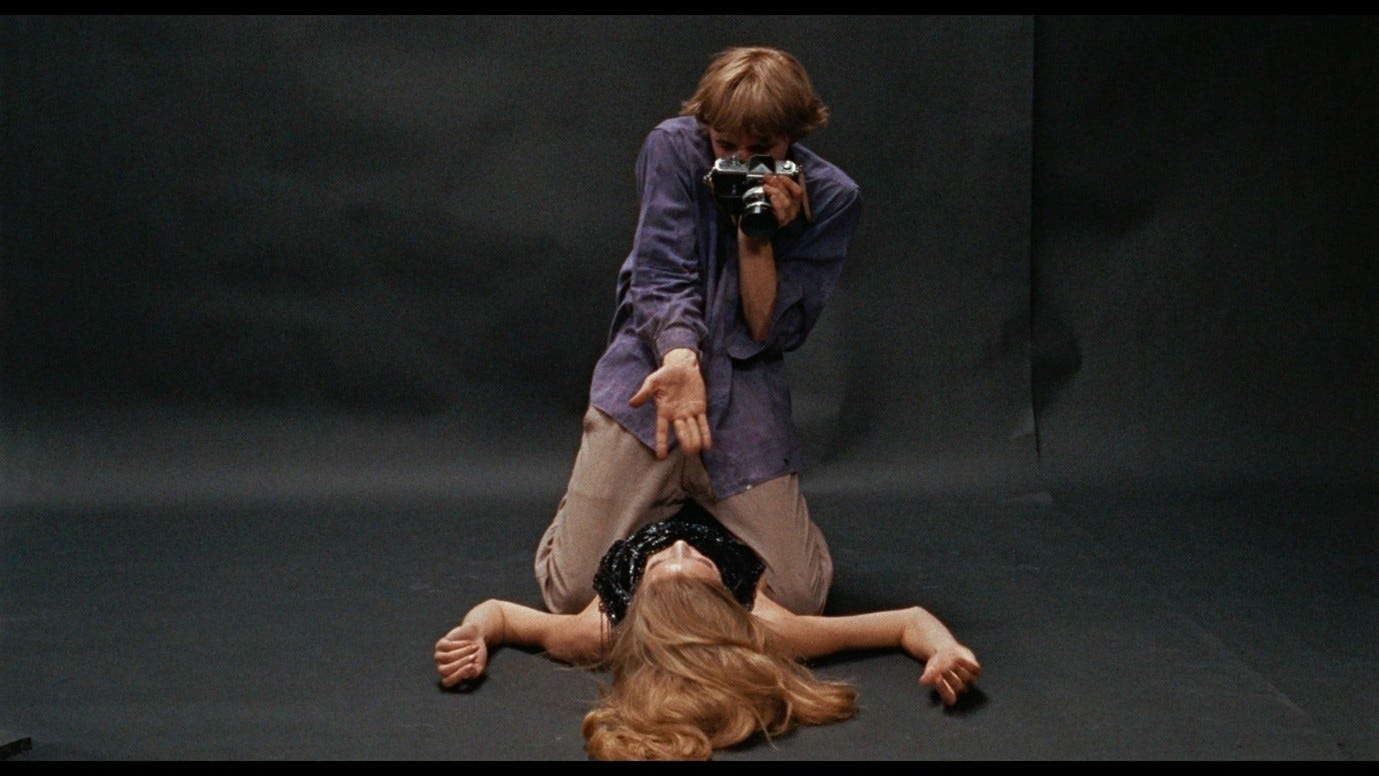

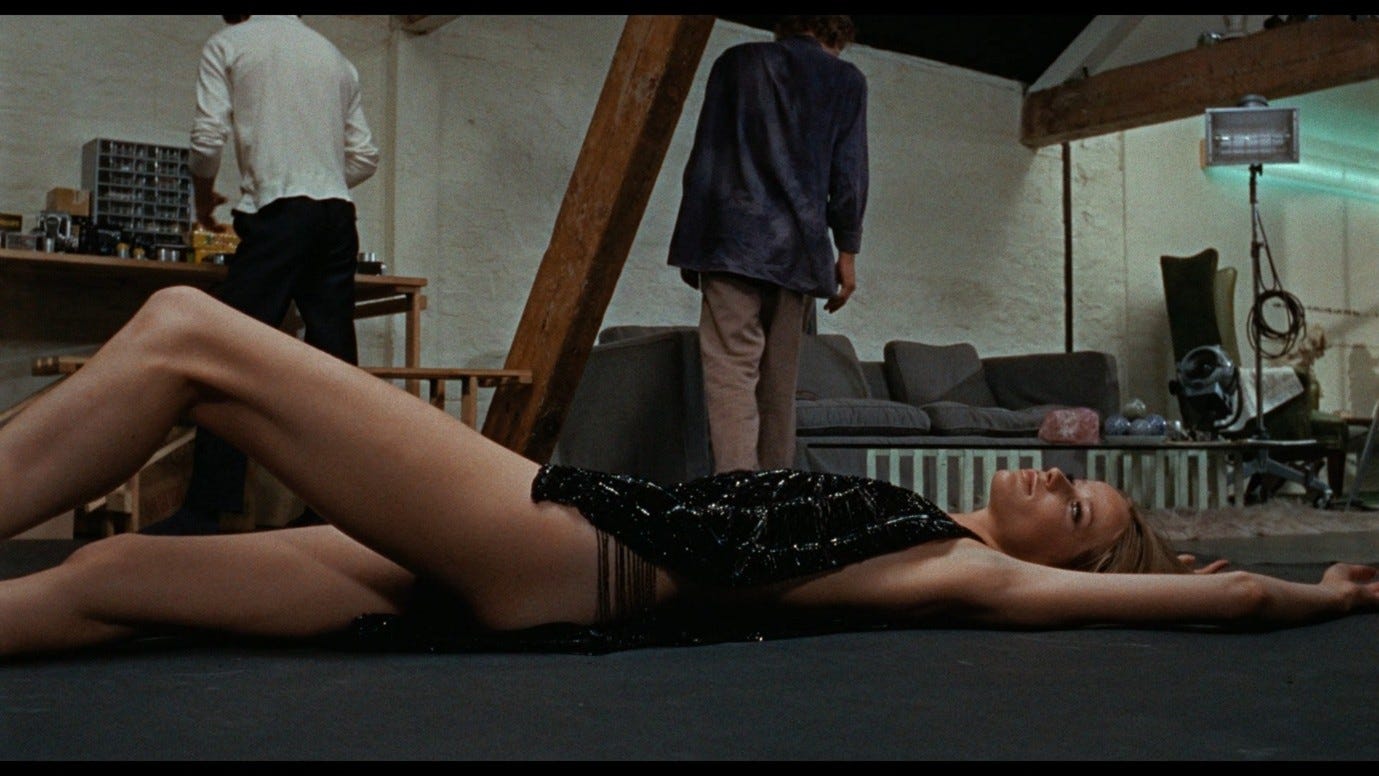

Indeed, we might re-appraise that circling camera movement around Giuliana from a few seconds earlier: does it prompt us to identify with her in a moment of un-mediated natural feeling, or is it an ostentatiously cinematic moment of male-gaze objectification, the attractive woman in crisis circled by the predatory camera? The photographer in Blow-Up looks at Verushka like this, demanding from her that want-to-make-love expression with more and more intensity, until he has extracted what he needs and she becomes one more dispensed-with object on the floor of his studio.

As Eugenia Paulicelli says:

Reality is always mediated; each photograph is both a construction and a reconstruction. Fashion photography simply makes more explicit the tension that already exists in any kind of rendering of reality.5

This comment applies most obviously to Blow-Up and the Lucia Bosè films, but I think the circling shot of Giuliana in the red room evokes something of the fashion-shoot mood. Giuliana intends to be completely sincere, but the camera makes her seem to perform like Verushka, insisting on that tension Paulicelli finds in any ‘rendering of reality’ – here, the rendering of desire through speech and action.

When the characters in Red Desert are tearing the shack apart, they quickly form a production line, with Corrado at one end and Giuliana at the other, feeding the stove.

Kinetic editing and camera movements emphasise connectivity, and as in the red-room scene the communal laughter creates a festive, liberated atmosphere. Richard Harris, finally allowed to do something physical, seems momentarily happy to be in the film.

It is the antithesis of the automated industrial processes that govern the factories: these are human beings, working with their hands, cooperating with each other for their mutual benefit, in resistance to the balding, bourgeois property-owner. The production line in Max’s shack seems like an escape to a simpler time, when people worked together to collect wood and transport it to the communal bonfire. It also feels (a little) like a piece of collaborative avant-garde art or theatre, as noted by Angela Dalle Vacche:

By changing the amount of red included in the shot, Corrado’s destruction of the decor makes us aware that our perception of chromatic relations between characters and costumes, characters and objects, is subject to variations at the level of framing and composition. With its downplaying of narrative development for the sake of a free interaction of people and things, of red and other colors, this episode resembles a happening (a typical activity among the theatrical avant-garde of the sixties).6

Max’s shack has been carefully constructed, decorated, and colour-coded with specific aims in mind, to make specific things happen in this space. This ‘happening’ initiated by his guests was not part of his plan. Dalle Vacche makes Corrado into one of the film-making crew: he ‘changes the amount of red included in the shot,’ as though his motive here were not just ‘this room needs more warmth’ but ‘this scene needs more red.’ The convulsive laughter that erupted in the red room now spills out into the rest of the shack, but also into this scene, transforming the glum tone into one of infectious joy – infectious among the characters and perhaps also among the cinema audience.

But then, as though a switch has been turned off, the laughter stops. The switch that has been turned off is in the Red Desert editing room: the tone changes within a single cut, from Giuliana throwing her head back and laughing – the high point of the scene – to Corrado looking suddenly abashed and shrugging apologetically. He looks at Giuliana, who sadly puts down the plank she had been holding and moves across the room.

The camera, now calm again, pans with her, surveying both the room and the characters, and revealing several interesting things. Before, everyone except Max was laughing. Now he is the only one laughing, in a rueful and mirthless tone. If the preceding action constituted a subversion of his authority, the aftermath renders that subversion trivial. Max now has the air of an embattled father laughing over the mess his children have made. Looming behind him are the walls of the red room, fully visible now that the partition has been torn down.

The screenplay comments on the effect of this exposure:

Surrounded by the red of the walls, the rumpled bed, now visible from the other side, vividly recalls the useless and absurd [inutile e assurdo] excitement of a short time ago, making Giuliana ashamed for everyone.7

The reference to the ‘excitement of a short time ago’ draws a link between the hilarity within the red room and the hilarity of tearing down the partition. Both outbursts of joy fizzle out bathetically, and both are retrospectively dismissed as ‘useless and absurd.’

In his interview with Godard, Antonioni explained the use of red in this scene:

[I]n the scene in the hut where they are talking about drugs and stimulants, I couldn’t not use red. In black and white it would never have worked. The red puts the viewer into a state of mind that allows him to accept such dialogues. It’s the right colour for the characters – who, in turn, are justified by the colour – and also for the viewer.8

Just as the mirror (according to the screenplay) indicates that the room is designed for sexual encounters, so the red paint also determines the mood and behaviour of the room’s inhabitants. Likewise, we as the audience are prepared to accept the film’s shift into frank eroticism thanks to the conditioning effects of colour. Antonioni says he couldn’t not use red in this scene, emphasising the deterministic worldview that dominates the film. Feelings are determined and conditioned, and his characters cannot not behave as their circumstances demand. The outbursts of feeling in the two moments analysed above are responses to environmental stimuli; they represent a kind of impulsive grasping for pleasure or warmth that dies out as suddenly as it begins.

In a statement accompanying the Cannes premiere of L’avventura, Antonioni argued that the prevalence of eroticism in contemporary culture

is a symptom of the emotional sickness of our time. But this preoccupation with the erotic would not become obsessive if Eros were healthy, that is, if it were kept within human proportions. But Eros is sick; man is uneasy, something is bothering him. And whenever something bothers him, man reacts, but he reacts badly, only on erotic impulse, and he is unhappy. The tragedy in L’avventura stems directly from an erotic impulse of this type: unhappy, miserable, futile. To be critically aware of the vulgarity and the futility of such an overwhelming erotic impulse, as is the case with the protagonist in L’avventura, is not enough or serves no purpose.9

The impulses which Antonioni describes as vulgar, futile, and unhappy have something in common with the so-called ‘useless and absurd’ behaviour in Max’s shack. The breaking of the partition is initiated when Corrado, frustrated by his thwarted desire for Giuliana, kicks down one of the boards.

Later, when he has torn out the other boards, smashed the chair, and finally snapped out of his excitable state, he seems embarrassed at having inadvertently and inappropriately displayed his feelings. The Cannes statement implies that it is precisely the ‘overwhelming’ nature of such feelings that makes them so vulgar and futile. We, as individuals and as a culture, are uncontrollably preoccupied with Eros to the point of obsession, to the point that we suffer from a malattia dei sentimenti.10 Antonioni insists that becoming aware of this illness, or even ashamed of it (like the characters in this moment in Red Desert), will not cure it.

If, on the one hand, the problem in question stems from uncontrollable impulses, it also stems from the conventional morality that our culture deliberately and systematically promotes. These morals, Antonioni says,

condition us without offering us any help; they create problems without suggesting any possible solutions. And yet it seems that man will not rid himself of this baggage. He reacts, he loves, he hates, he suffers under the sway of moral forces and myths that today, when we are at the threshold of reaching the moon, should not be the same as those that prevailed at the time of Homer, but nevertheless are. Man is quick to rid himself of his technological and scientific mistakes and misconceptions. Indeed, science has never been more humble and less dogmatic than it is today. Whereas our moral attitudes are governed by an absolute sense of stultification. In recent years, we have examined these moral attitudes very carefully, we have dissected them and analysed them to the point of exhaustion. We have been capable of all this, but we have not been capable of finding new ones. We have not been capable of making any headway whatsoever toward a solution to this problem, of this ever-increasing split between moral man and scientific man.11

I struggle to grasp Antonioni’s argument in the Cannes statement, and it is important to note his disclaimer that he cannot resolve these issues himself: ‘I am not a moralist, and my film is neither a denunciation nor a sermon.’12 For me, his comments are much like the dialogue in his films, suggestive but elliptical, incisive but inarticulate. Several conflicting things are being said between the lines, and they are not spelt out because they are not supposed to be.

A few years before Red Desert, Antonioni and Tonino Guerra wrote a treatment for a film to be called Makaroni, about liberated prisoners in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, overcome with a euphoria that dissipates as they resume a peacetime existence. In the following passage, the characters (with one exception) indulge in an orgy of destruction that resembles the dismantling of Max’s shack:

Roberto can’t control himself any more: he’d like to destroy the whole lot, as if those papers represented something old and orderly that no longer has any reason to exist. Now there is freedom, every individual is his own master, no more lists or files. Elly is the only one of the group not to let herself get carried away by this frenzy of freedom. She knows that the most important thing at the moment is to get out of the chaos and start rebuilding a quiet, normal life.13

Roberto vacillates between cultivating a relationship with Elly and cheating on her with various other women he encounters. He and Elly are somewhat like Sandro and Claudia in L’avventura; his behaviour is governed by impulse, she is seeking order and stability. Looking back on this treatment just before beginning work on Red Desert, Antonioni remembered that Makaroni was inspired by conversations with survivors of the war:

To the question, ‘What was the worst time of your life?’ they all replied, ‘The concentration camp.’ And to the question, ‘What was the most beautiful time?’ they all said, ‘Immediately afterwards.’ […] [T]here was disorder, chaos, freedom in its raw state. […] [I]n our life today, with our social duties on the one hand and our morality on the other, there is no room for adventure.14

As in the Cannes statement, we find conflicts between the lines: Antonioni makes it sound as though this film would have been a celebration of the avventura of post-war liberation, a nostalgic re-enactment of this moment when people experienced ‘freedom in its raw state.’ But in the treatment itself, Roberto’s adventures seem more complex than this, his malattia too profound to be cured by smashing up ‘something old and orderly.’ Later, he has another burst of euphoria, but it quickly vanishes:

Once again, he feels ashamed, as if what he is doing is a useless gesture, and […] he’s seized by a sense of futility again.15

Towards the end of the story, Roberto tries to articulate his fear of the ‘quiet, normal life’ that Elly wants to return to:

I’m afraid of going back to being a normal person, with a peaceful, tidy life after all this horror and then all this freedom. I’m afraid of everything that we’ll have to do to live in peacetime, having a family and normal, social routines. I’m afraid it’s too difficult, and I don’t even know who I could live with like that. I’m a wreck, rotten. I’m afraid that everything we’ve been through will turn out to be the only thing that ever happens to us in our lives. Do you know what I mean?16

Both Roberto and Sandro reject the outdated moral myths about human relationships, but neither can find an alternative way of living. Roberto’s coupling of horror and freedom is important here: it is not just that he has tasted some form of Edenic happiness and now, tragically, has to give it up; it is not just that his capacity for joy has been excited and must now be displaced. Rather, there is something about ‘all this horror and then all this freedom’ that accounts for Roberto’s malattia, his Giuliana-like sense of being ‘a wreck, rotten.’ His comment about ‘everything we’ve been through’ becoming ‘the only thing that ever happens to us in our lives’ anticipates Giuliana’s line, ‘Everything that happens to me is my life.’ Roberto frames the horror/freedom not as a golden age whose loss he will always mourn, but as a trauma he will never get over, a moment to be repeated compulsively for the rest of his life.

The horror/freedom pattern, as it is presented in Makaroni (a transition from imprisonment to freedom), recurs in different ways in L’avventura. It is there in Anna’s depression and disappearance, in Sandro’s relationship with Claudia, and in his betrayal of her at the end, followed by their ambiguous reconciliation, juxtaposed against the distant volcano and the nearby blank wall.

The absolute constriction and subjugation of imprisonment is succeeded by a state of absolute openness; the claustrophobic relationship vanishes into thin air; Sandro is free to sleep with anyone, and to inflict unlimited anguish on himself and Claudia in the process. How could Roberto return to normal life, and how could Anna return to Sandro or to this social circle, after all this horror and then all this freedom? The link with Giuliana’s problem becomes clear if we look at this pattern in terms of imprisonment/liberation, because one of the central conflicts she grapples with is her mingled desire for and horror of containment; and her mingled horror of and desire for dissolution.

In the scene we are examining in Red Desert, we witness a series of impulsive outbursts and deflated hangovers. The characters momentarily experience a utopian sense of free love and communal togetherness, and in these moments there is a hint at the new mode of life Antonioni suggests we should envision. In an interview with Playboy in 1967, he spoke admiringly of the younger generation who were ‘seeking a new way to be happy,’ who were finding new ways to protest:

In California’s ‘loving parties’ there is an atmosphere of absolute calm, tranquillity. That, too, is a form of protest... It’s a complicated subject – more so than it seems – and I can’t handle it, because I don’t know the hippies well enough.17

Antonioni went on to make Zabriskie Point, whose desert orgy scene is, in one sense, a fantasy of what Eros might look like once it has been cured of its sickness, but is in another sense indicative of the director’s distance from this brave new world. Peter Brunette, explaining his own ambivalent reaction to this sequence, cites another Antonioni interview:

[I]n its celebration of a hippie orgy in the desert – no matter how magnificently composed, visually and aurally – the film also serves as a tacky and embarrassing record of the fifty-six-year-old director’s own presumed sexual liberation (or wish-fulfillment). In an interview with Look magazine at the time, Antonioni said: ‘America has changed me. I am now a much less private person, more open, prepared to say more. I have even changed my view of sexual love. In my other films, I looked upon sex as a disease of love. I learned here that sex is only a part of love; to be open and understanding of each other, as the girls and boys of today are, is the important part.’18

Like Brunette, I find the Zabriskie Point orgy both beautiful and embarrassing, and the embarrassment stems partly from the sentiments Antonioni expresses in that last quotation. The film seems, at times, to pander to an imagined audience of ‘the girls and boys of today’ whose alleged ‘openness and understanding’ is really a euphemism for the mass orgies Antonioni wants to stage and film. However, it is worth looking at the next few sentences from that interview, which Brunette leaves out:

But it is not fair to ask questions of me before I put my picture together. The responsibility is mine. It is me in front of the camera saying what I feel about my America.19

Antonioni has just been saying that America has changed him and that he has learnt something from the hippies, but then he seems to correct this: it will not be America’s effect on him that ends up on the screen, but his feelings about his version of America, and these will only emerge when he edits the film together. Indeed, it will be him ‘in front of the camera,’ not the hippies. The nostalgic postwar euphoria in Makaroni, the liberation from monogamy in L’avventura, the hilarity in the shack in Red Desert, and the Zabriskie Point love-in, all represent emotional states that Antonioni feels drawn to. He would speak of these moments as he speaks of the hippies in the above-quoted interviews. But in each case, when it comes to putting the film together, something goes wrong, and this ‘something gone wrong’ is what the film is really about.

In Zabriskie Point, we see the transition Antonioni describes – from seeing sex as a ‘disease of love’ to seeing it as part of the openness and understanding between people – but then we see this transition reversed, the disease of love reasserting its dominance. ‘It didn’t look the way he imagined it,’ says Beverly Walker in an interview with Murray Pomerance; and Antonioni told Marsha Kinder, ‘I never saw this idea as something real. I didn’t have the image […] I was looking for something different – something which was more related to the special character of Zabriskie Point.’20 Antonioni planned an apocalyptic finale, described as follows in the script:

After a bit, a light breeze springs up. Then it blows harder and harder. All the boys and girls have to quit their love-making. They stand up. The wind is blowing so hard now they have trouble even standing up. Great gusts of dust blow into their faces so they can hardly breathe. They struggle away through the dust, towards any shelter they can find – hand in hand. They have their arms around one another as they push ahead. The hot desert wind is a force of nature, destructive as a whiplash – a screaming curtain of black dust against which the young couples are seen battling desperately, as they appear now and then in the distance.21

Pomerance sees this would-be conclusion to the desert orgy as ‘apotheosiz[ing] the struggle of this young generation against forces malevolent and overwhelming.’22 The hippies have their arms around each other and battle against the dust-cloud hand-in-hand, suggesting those bonds of mutual affection that Antonioni seemed to idealise. This is less hopeful than the initially planned love-making would have been, but the final version of the scene, as filmed and edited, strips away even that sense of solidarity and connection. The love-making takes place in Death Valley, a setting populated (before the hippies arrive) by dead bodies turned to sand, and the sand quickly covers the love-making bodies, making them seem paler, more death-like. The hippies do not struggle heroically, together, against the dust of malevolent forces; they fall asleep as it slowly buries them (see also Part 14).

The melancholy that washes over the final moments of the desert orgy is like the shame that washes over the characters in Red Desert. Those red walls awaken natural instincts and bring us closer to fulfilling them, and when the walls are opened up this feels warming and liberating. But then the characters find themselves inhabiting a desert, a place as desolate as it is open, at once a land of wondrous new opportunities and a land laid waste where nothing can thrive. Tomasulo and McKahan see Antonioni’s world as

caught in an interregnum, a transition phase between an old, outdated morality with puritanical strictures and a new consciousness that seems to promote free love but is fettered by post-industrial capitalism’s spirit of competition and acquisitiveness. This new morality conspires to diminish our humanness and reduce our free psychological response to the transcendental pleasures of love and true Eros.23

An attempt at ‘free love’ that is undermined by the spirit of capitalism is, to some extent, what we get in the red-room scene in Red Desert, with Max the sexual/industrial predator poisoning the would-be love-in with his authority over and authorship of this ‘liberated’ space. Something like that also seems to have been intended in the un-filmed ending to the Zabriskie Point orgy, where the young people were battling against insurmountable forces (represented by the dust storm). In neither film, however, do I get a sense that ‘the transcendental pleasures of love and Eros’ would be accessible in the absence of capitalism, or that the problem with this new morality is that it ‘diminishes our humanness.’ For better or worse, I think that Antonioni is less political and less of a moralist – less invested in ‘humanness’ – than these terms would suggest.

In a 1976 article about L’avventura, Antonioni said that the film is about ‘the pain of feelings that come to an end, or in which you catch a glimpse of the end at the same moment when they are born.’24 I find this a more comprehensible variation on his philosophising about ‘Sick Eros’: all the talk about a changing world, outdated ideas, and the need to forge a new way of living, all of this perhaps boils down to something like the Japanese concept of mono no aware, the pathos of transience. In Red Desert, the countryside blighted by monstrous factories is an extreme manifestation of transience, a brutal reminder that the environment itself is subject to change. It is a type of change driven by exploitation – the land changes because it is plundered, combusted, and used as a receptacle for effluent – and human relationships are affected by these exploitative processes as well. But deep down, these abuses of places and of people are distressing because ‘feelings come to an end,’ because even in the beginning the end is glimpsed looming over the horizon.

The sadness in L’avventura resides not just in the changeability but in the disposability of people. We seek a deep, loving connection (the transcendent pleasures of love) and instead find ourselves exploiting and being exploited. In a state of leisure, with nothing to do but ‘relate’ to each other and ourselves, it becomes harder to avoid seeing these relations for what they are. In Red Desert, Max’s shack serves as a sort of crucible – a claustrophobic variation on the island in L’avventura or the desert in Zabriskie Point – where people are crammed together and the distances between them are thrown into relief. They have escaped from the oppressive conventions that normally weigh them down, and from time to time they briefly experience that Californian sense of ‘free love’, that seemingly new way of living. But (these films seem to say) we will never find this new way of living. It does not exist. There will only be the same fitful pursuit of emotional connection, inevitably exploitative, and just as inevitably bringing a sense of shame and futility in its wake, before the dust storm (or the fog) comes in and buries us all.

The relationship between exploitation, disposability, and transience becomes more of a focus for Red Desert from this point on. To anticipate something Giuliana will say at the end of the film, we might think of the shame experienced by the characters in the red room as the shame of bodies that think they can connect, then suddenly realise they are helplessly separate; bodies that think they are bound together, then suddenly realise they are disposable to each other. ‘If you prick me, you don’t suffer,’ Giuliana will say to the Turkish sailor. Her encounter with Max is one of the steps that will lead her to that insight.

Matilde Nardelli makes an important observation about the redness of Max’s red room:

The tendency is to see the red in the shack especially as exemplary of Antonioni’s pursuit of abstract painting. […] Yet, for all its abstractness, it remains, unmistakably, vernacular red paint – unevenly applied, damaged and visibly touched up with different hues – on wooden planks; planks, in fact, that the characters at a point tear down to burn in the stove for warmth.25

For Dalle Vacche, as we saw earlier, the opening up of the red room makes us aware that ‘our perception of chromatic relations between characters and costumes, characters and objects, is subject to variations at the level of framing and composition.’26 The tearing down of the planks not only alters the framing – the aspect ratio – within which we see this pro-filmic space, it also reminds us of the space’s materiality, of the fact that these planks have been put together and painted. As Nardelli says, there is something significant about the hand-made-ness of this setting. A few people built this shack; it could have been painted by just one person, perhaps Max himself; and seeing it get ripped apart and handed, in pieces, from one set of hands to another, intensifies our sense that this sequence is about an interpersonal red desert, where the red-ness has been daubed on by an individual and the desert-ness reflects something about our relationship to that individual.

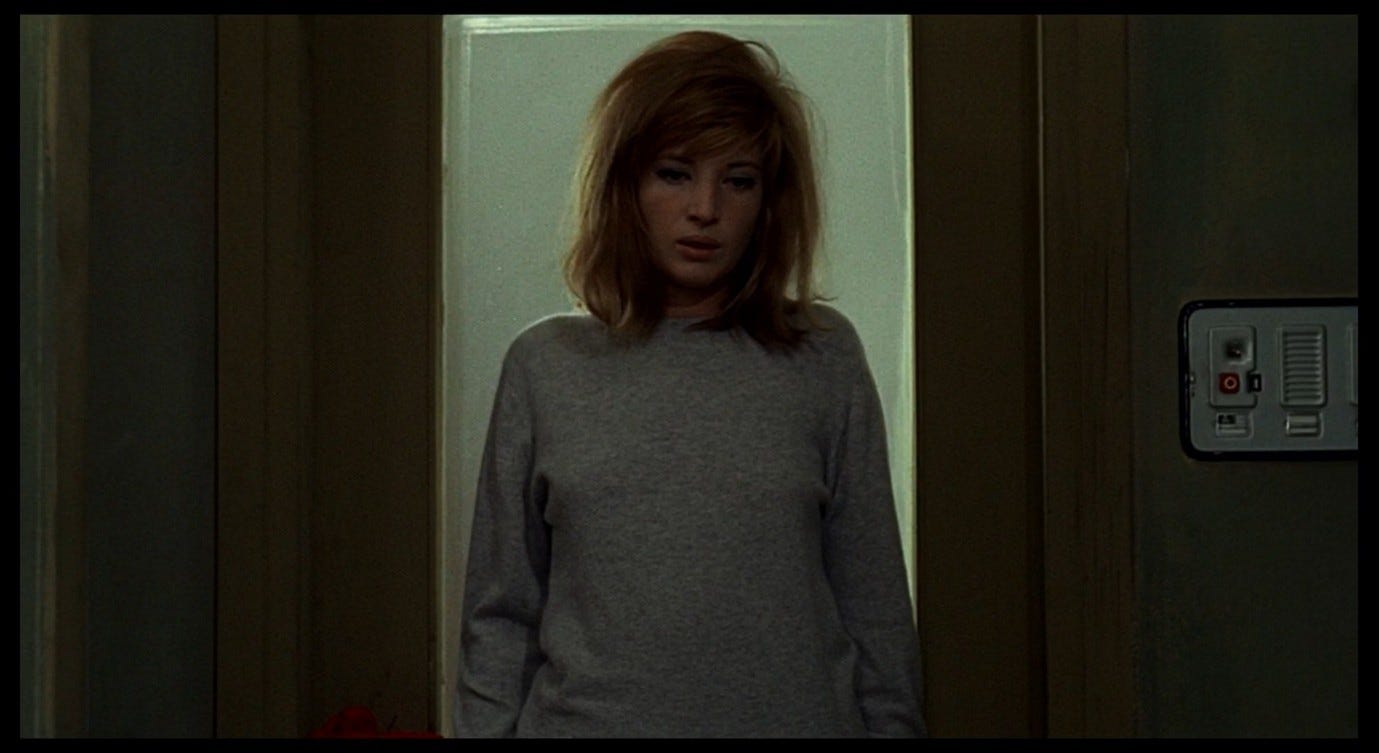

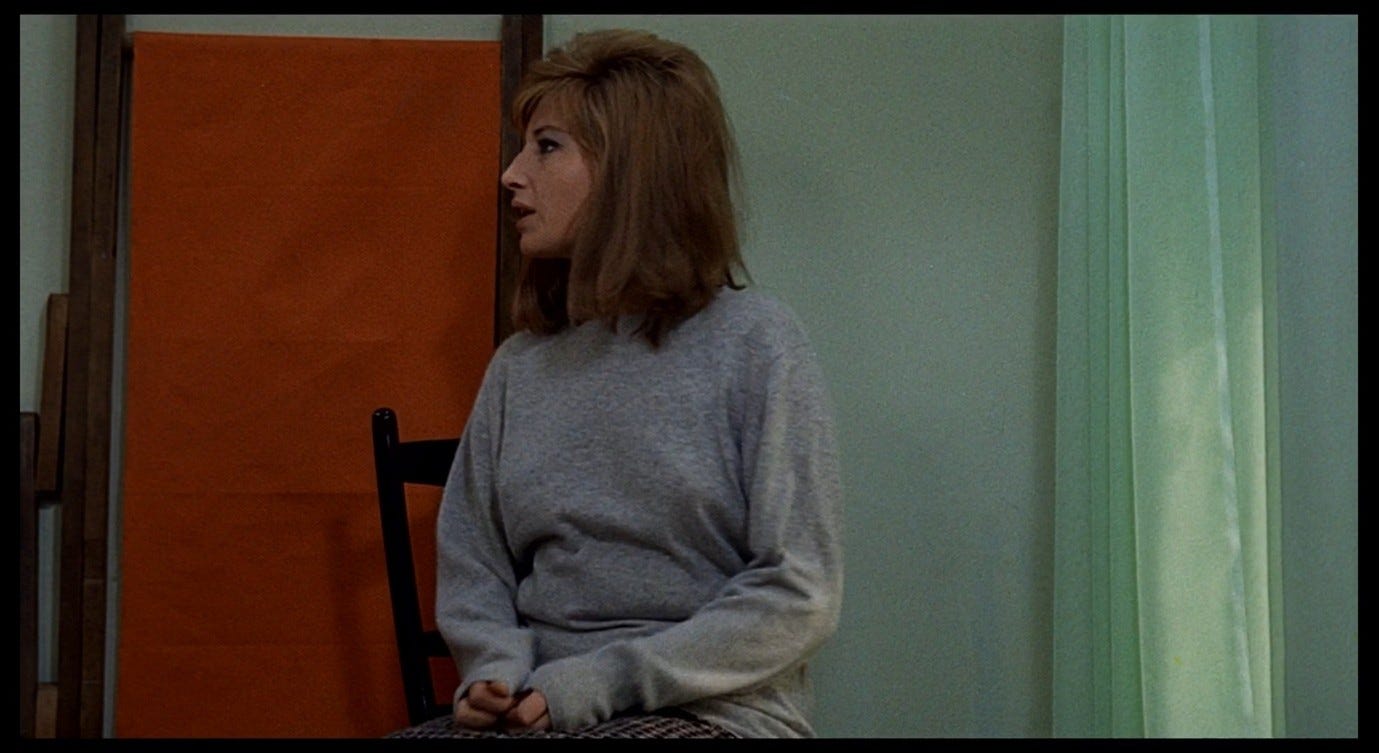

This is a different kind of constructed space, and a different way of using colour, from what we saw in the Ferrara/Medicina sequence, where the buildings and colours partook of a robotic uniformity. When Mario’s wife greets Giuliana and Corrado, she is wearing a bright red apron, which she quickly takes off and hangs on the door; we see it there when Giuliana stands in front of that door to describe her (or the ‘other woman’s’) sensation of losing the ground beneath her feet. At first, it is barely visible at the bottom of the frame; we see it more fully when we cut to the wide shot.

Then, when Giuliana sits down opposite the sofa, she is framed between a reddish-orange deckchair and the light green of the walls and curtains.

Green pervades Mario’s home, like a ‘cool’ colour that is so intent on calming us down that it becomes agitating. The deck-chair stands behind Giuliana, a harbinger of more intense, painful emotions. But it is also a flattened-out object, a three-dimensional chair that has been made two-dimensional and stacked against the wall. The visible creases in the fabric call attention to the fold-ability of this object, and their positioning makes me wonder if they inspired Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, Attese (see Part 11).27

Fontana’s intent in slicing through the canvas was to transform two dimensions into three, but again Antonioni seems more interested in the opposite transformation, from depth to flatness. Like the red apron hastily taken off and put out of the way, then brought back into frame, then excluded again, the deckchair reminds us of Red Desert’s title – which primes us to look out for instances of this colour – in a way that is both conspicuous and subliminal. The ‘blood’ of the red desert is always there, always visible, but always repressed, never spoken about directly.

Here is Antonioni’s statement (quoted in Part 7) about factory-produced colours:

In Red Desert, we are in an industrial world which every day produces millions of objects of all types, all in color. Just one of these objects is sufficient – and who can do without them? – to introduce into the house an echo of industrial living. […] When, around the turn of the century, the world began to industrialize, factories were painted neutral colors – black or gray. Today, instead, most of them are brightly painted. […] Behind this invasion of color lie technical causes, but also psychological ones. The walls of the factories are colored not red, but light green or pale blue – the so-called ‘cool’ colors, on which the workers can rest their eyes.28

As she describes her time in the clinic, Giuliana is surrounded by the kind of cool colours that were no doubt used in that clinic to encourage the patients to ‘rest their eyes.’ But these colours too, especially when applied with such perfect uniformity, are ‘an echo of industrial living,’ and as such they inevitably bring the red desert with them, lurking like the Babadook in corners and against walls. The effect of colours is not as clear-cut as Antonioni suggests in the above-quoted interview; indeed, he is setting up this join-the-dots conception of how colours influence emotions in order to complicate it.

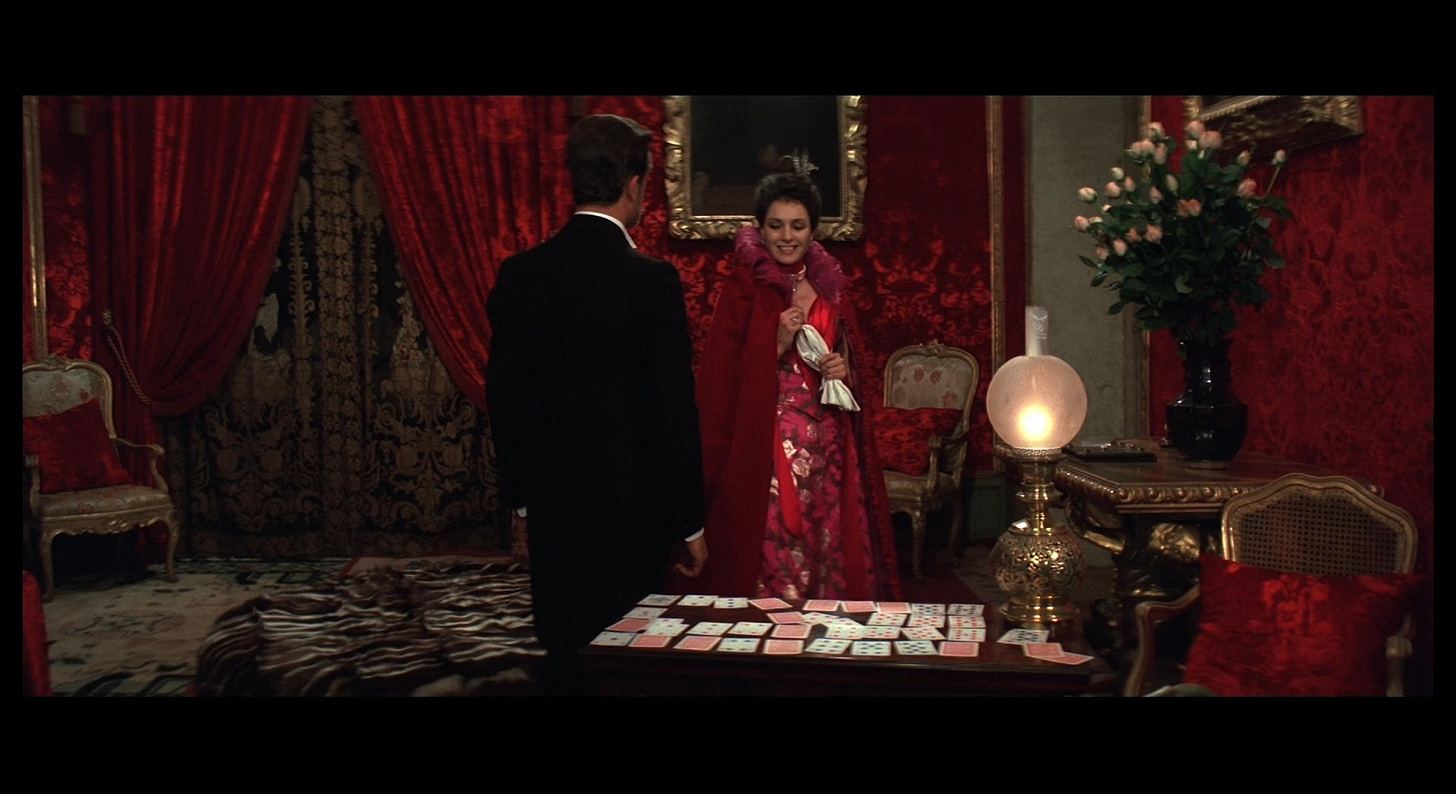

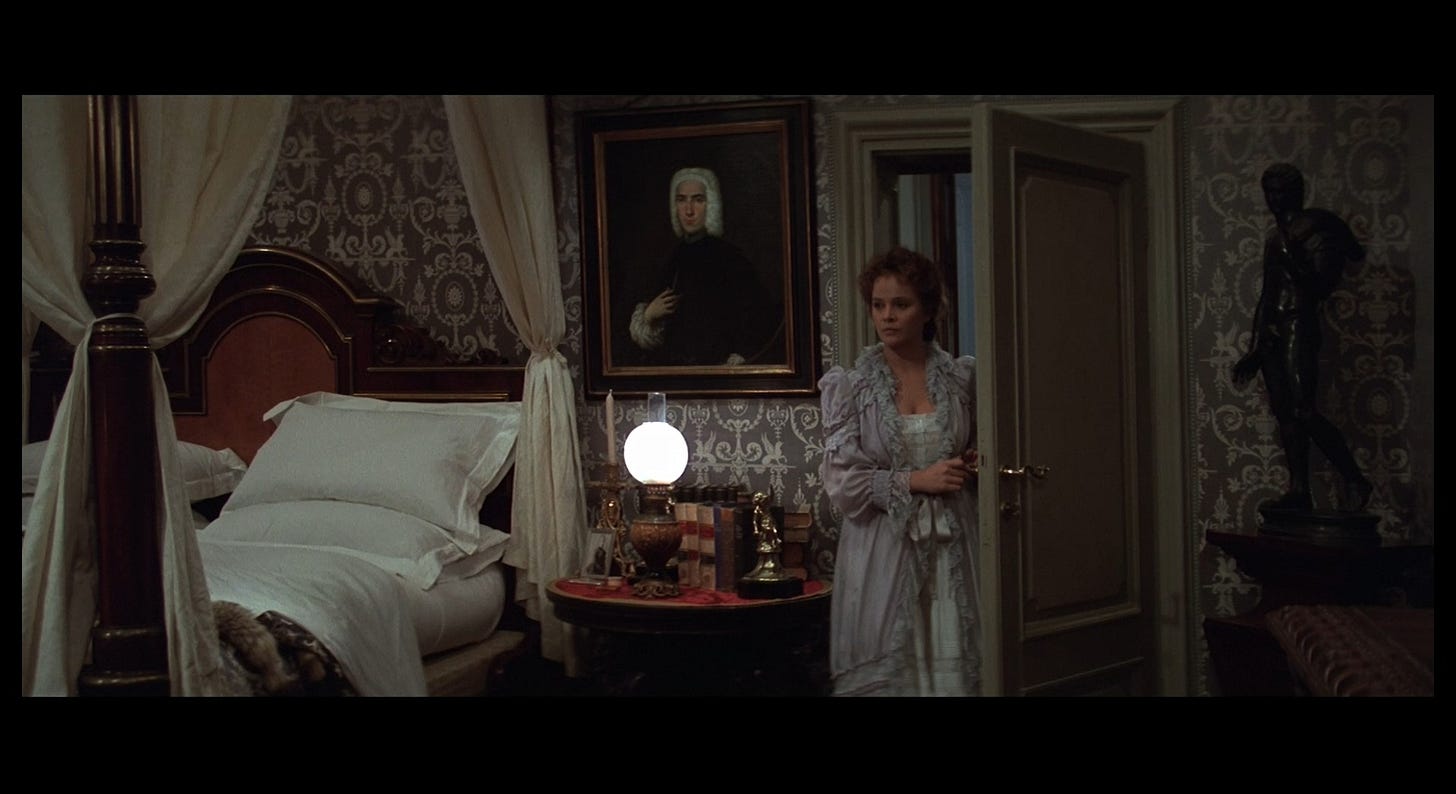

Visconti does something like this in L’innocente: we see Tullio with his mistress (with whom he is, for the moment, passionately in love) in an overwhelmingly red room, then we cut to his life at home with the wife he has grown tired of, in an overwhelmingly grey room.

Later, as the emotional configurations between the characters become more complex, beyond the expressive capacity of ‘red vs. grey’, we see the wife putting on a pink veil that makes her face resemble a painted canvas; then we see her, dressed all in pink, framed (as Tullio sees her) in a doorway to the colourful, sunlit, outdoor world, contrasted with the staid, beige interior.

Visconti establishes certain tones, certain colour-codes, in order to complicate them, in ways that surprise the audience and leave us feeling intense emotions that are hard to define. Red Desert is a long way from the violent melodrama of L’innocente, but it is also asking us to ‘feel’ these colours and then feel them differently – to sense how the colours are working on us and how we are working against them. Yes, cool colours are there to calm us down and hot colours are there to excite us, but all of them are part of the broader ‘invasion of colour’ and all carry ‘echoes of industrial living.’ Light green can induce a sense of unease insofar as it seeks to repress our emotions, and red can induce a sense of relief insofar as it puts us back in touch with those emotions. Mario’s wife has to be polite to her visitors, so she puts away the glaring red apron, but she leaves it hanging from the door-handle and she firmly (albeit politely) tells Corrado to stay away from her vulnerable husband, gesturing towards that ‘red’ intensity. Giuliana has to follow the doctors’ anti-disturbing, light-green advice and explain to her ‘self’ who ‘she’ is – ‘Now she is cured,’ she has to say – but she positions herself against the reddish fabric of the deckchair (flattened out, like she feels) and belies her own claims of wellness with her depressed, anxious tone of voice. She wears a grey sweater, a small reminder of the fruit that turned grey in her presence a few minutes earlier.

Red Desert thus trains us to respond to colours in a nuanced, sceptical way, conscious of these colours’ intended functions and able to think beyond them, to notice the rosso hidden within the celeste e verde. Max’s shack is blue on the outside, with a red room-within-a-room inside. To paint the outside red would be a too-overt signal of the building’s purpose; blue goes better with the sea and the sky, and disappears easily into the fog. But we do not get a clear view of the blue exterior until some way into the quasi-orgy sequence – when Orlando and his girlfriend leave – meaning that its intended effects only work on us after we have found out (from within) what the shack is for.

When Antonioni says that he ‘had to use red’ in this scene, this echoes what Max must have thought when decorating the shack: there has to be a red room here to get visitors in the right mood. However, this imperative to use red is deconstructed when the room is deconstructed. Why does it have to be red? If the red provokes erotic sensations for those inside it, what does it do to Orlando and his girlfriend, who are unable to enter the room (or have sex in it, as they had planned)? And what does it do to the others when they leave the room and, so to speak, bring it with them by pulling out the planks? The rest of the scene is hardly erotic, but it is emotionally intense. The transition from Giuliana saying ‘I want to make love,’ through her hilarity over the firewood, to her mounting distress and panic in the subsequent few minutes, illustrates the effect of the red paint, and the different levels on which Antonioni’s deterministic comment operates. He had to use red here, so that – as with the grey fruit or the pink flowers – he could show how colours can spiral out of control, like a cheerful melody that relentlessly increases in volume. This is how I understand his comments about ‘Sick Eros’ and the malattia dei sentimenti. The inconsistent, hand-painted quality of the red in Max’s shack ties the colour to human senses, foreshadowing later manifestations of colour that Giuliana will ‘feel’ more directly, like patterns drawn by hand, by a person (herself or someone else), spreading like toxic mould through her nervous system and her mind’s eye.

Next: Part 20, Something terrible in the fog.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 460

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 36

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 464

Coates, Paul, ‘On the Dialectics of Filmic Colors (in general) and Red (in particular): Three Colors: Red, Red Desert, Cries and Whispers, and The Double Life of Véronique’, Film Criticism 32.3 (2008), pp. 2-23; p. 13. See also Cinema and Colour: The Saturated Image (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 76.

Paulicelli, Eugenia, Italian Style: Fashion and Film from Early Cinema to the Digital Age (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p. 284

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 69

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 471

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 295

‘A talk with Michelangelo Antonioni on his work’ in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; pp. 33-34. The Cannes statement is quoted in full as part of this interview, and is also available on the Criterion website.

This phrase comes from the interview with Antonioni, ‘La malattia dei sentimenti’ published in English as ‘A talk with Michelangelo Antonioni on his work’, cited elsewhere in this post.

‘A talk with Michelangelo Antonioni on his work’ in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; p. 33. The Cannes statement is quoted in full as part of this interview, and is also available on the Criterion website.

‘A talk with Michelangelo Antonioni on his work’ in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; p. 33. The Cannes statement is quoted in full as part of this interview, and is also available on the Criterion website.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Makaroni’ (trans. Andrew Taylor), in Unfinished Business: Screenplays, Scenarios and Ideas, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 61-110; pp. 82-83

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Makaroni’ (trans. Andrew Taylor), in Unfinished Business: Screenplays, Scenarios and Ideas, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 61-110; p. 109

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Makaroni’ (trans. Andrew Taylor), in Unfinished Business: Screenplays, Scenarios and Ideas, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 61-110; p. 105

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Makaroni’ (trans. Andrew Taylor), in Unfinished Business: Screenplays, Scenarios and Ideas, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 61-110; p. 107

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Apropos of Eroticism’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 148-167; p. 150

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 23

Hamilton, Jack, ‘Antonioni’s America’, Look (18 November 1969), pp. 36-40. Available on trussel.com.

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp. 171-172

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 172

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 172

Tomasulo, Frank P., and Jason Grant McKahan, ‘“Sick Eros”: The Sexual Politics of Antonioni’s Trilogy’, Projections 3.1 (2009), pp. 1-23; p. 17

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The Adventures of L’avventura’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 78-81; p. 80

Nardelli, Matilde, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), p. 35

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 69

The image of Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, Attese (1965) is taken from Tait, Olivia, ‘Lucio Fontana’s Tagli’, Hauser & Wirth, 06 February 2019.

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; pp. 283-284