Everything That Happens in Red Desert (50)

Re-inserted in reality

This post contains some discussion of suicide.

In the final two minutes of Red Desert, we see Giuliana as we saw her in the first scene: dressed in her green coat, out for a walk with Valerio.

After the intensity of the last few sequences, the film ends on a note of relative calm, but also on a note of cyclical repetition. We are back where we started. In her final conversation with Corrado, Giuliana said that she had ‘reinserted herself in reality,’ as the doctors in the clinic had told her to. She framed this, with rueful irony, as a kind of ‘success’. This tone hangs over the final scene as well. Giuliana has succeeded in a way that feels like defeat, and now the film will end happily in a way that feels tragic.

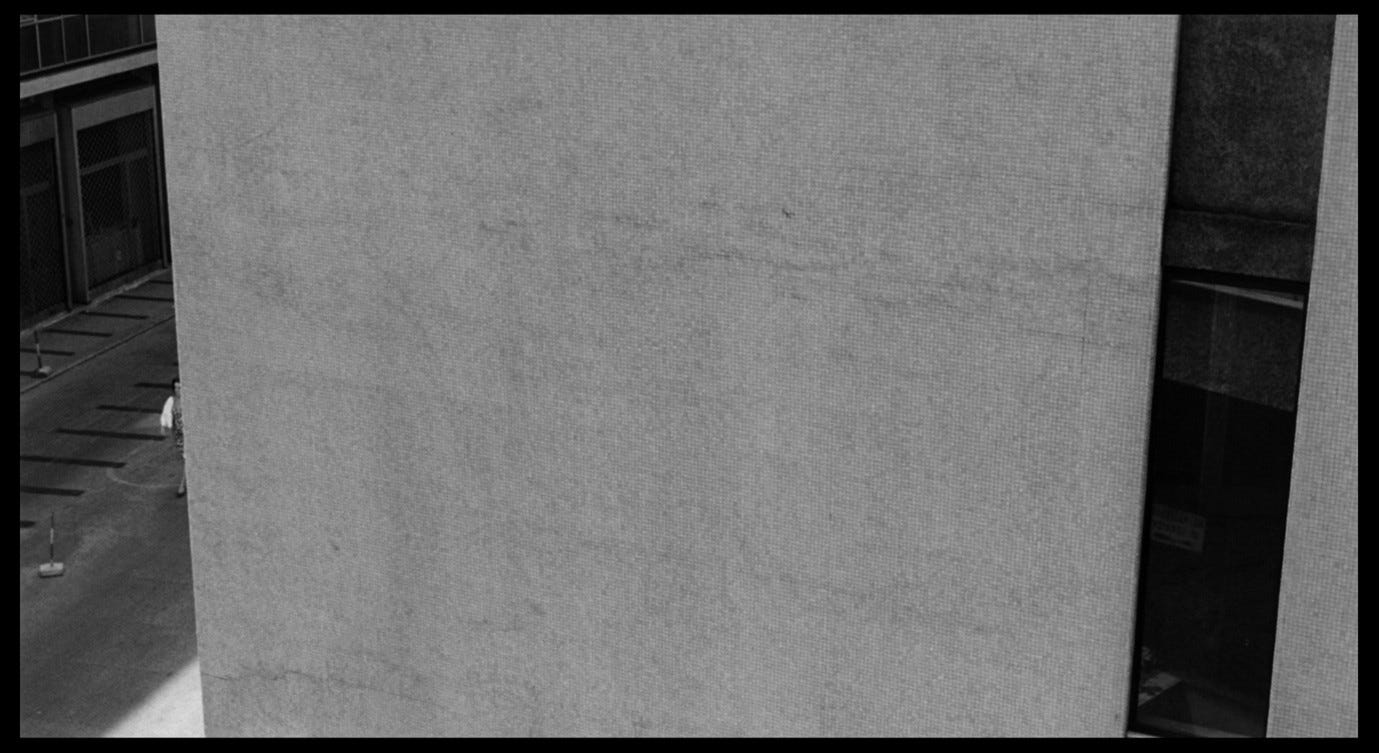

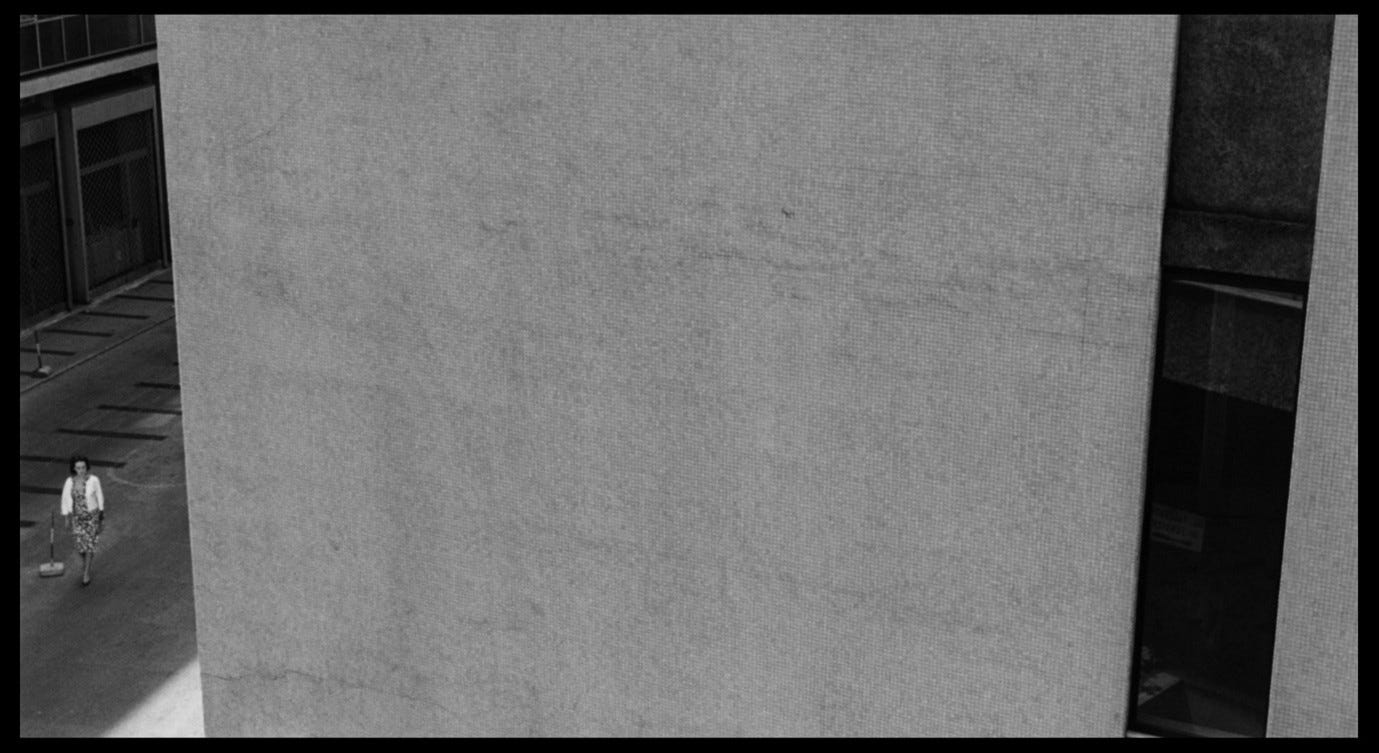

The dark final image of the harbour sequence, in which Giuliana (and then her shadow) disappeared into the night, is abruptly replaced by a daytime image of factory buildings.

We go from a high-angle shot, looking down on the vanishing Giuliana, to a low-angle shot staring up at these cylindrical towers. As she left the harbour, Giuliana was framed against the ground and against the pools of light and shadow cast upon it, but now the towers are framed against a solid grey sky. The transition here reiterates a common dynamic in Red Desert, between the worm’s-eye-view of the characters and the intimidating structures that dominate the skyline. We look down on Giuliana to see how small she is, then we look up at the monoliths that watch over her.

After the camera has tilted down and panned right to reveal Valerio playing with a steam vent, we cut to a wider shot in which a pair of trees are juxtaposed with the coupled towers on the left-hand side of the image.

This transition recalls the very first shot of the film, in which the camera panned from a cluster of trees to a cluster of factories. That image blurred the objects almost beyond recognition, but now they are as clear as day. Indeed, although these are the same towers we saw in that opening shot, seen from almost the same angle, they look so different that we could not be expected to recognise them.

The setting and tone of this scene have been established: it is daytime, among the factories, and here is Valerio; then we stand back and get a broader view of the space; then we hear Giuliana’s voice calling Valerio, and we are fully oriented as to what is happening. This world appears ordered and unified. The towers are together, the trees are together, and Valerio is about to be reunited with his mother. The imagery connotes harmony, but as with the pink flowers outside Mario’s apartment block (see Part 16), the harmony seems forced and robotic. Valerio, whose attention is focused on the steam vent, notices but resists his mother’s call, and Giuliana herself does not appear until the next shot. As Valerio demonstrated with his chemistry set, one plus one can still equal one – just because his mother is with him does not mean they are together.

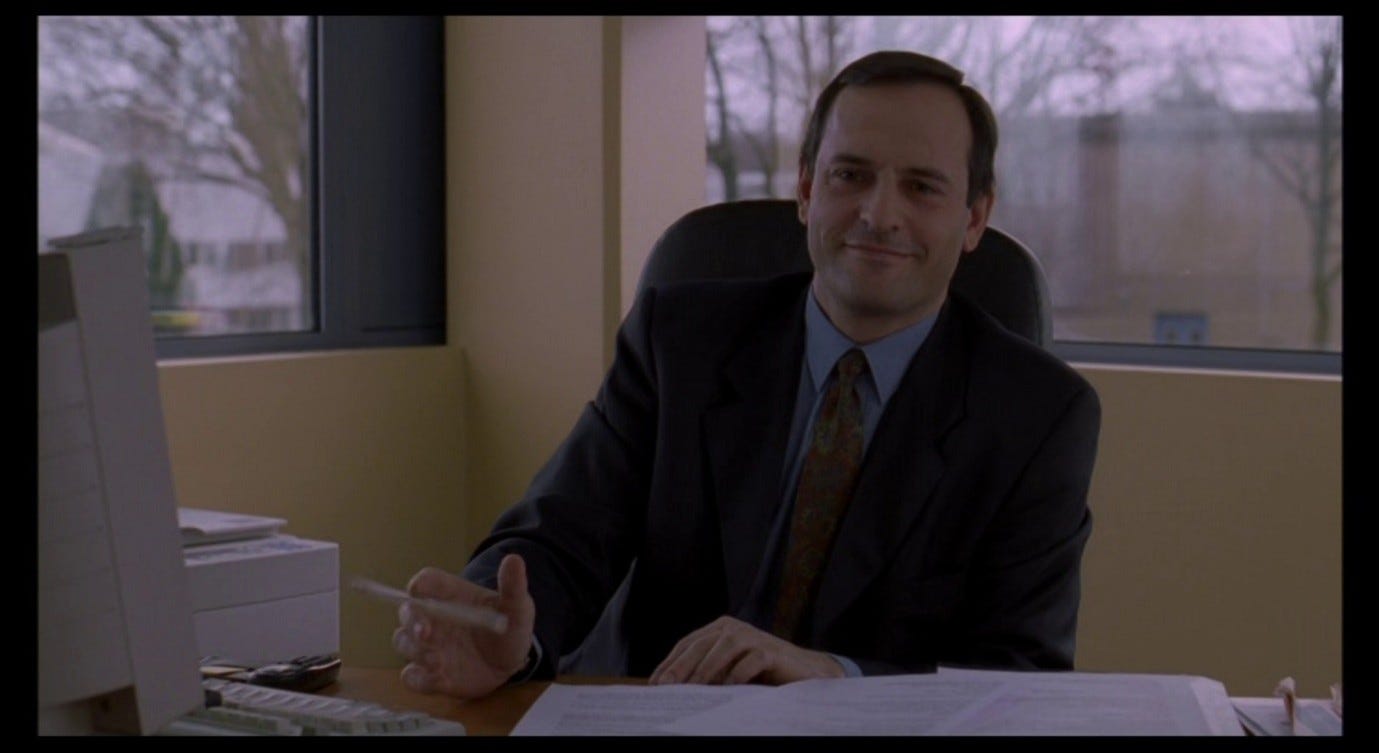

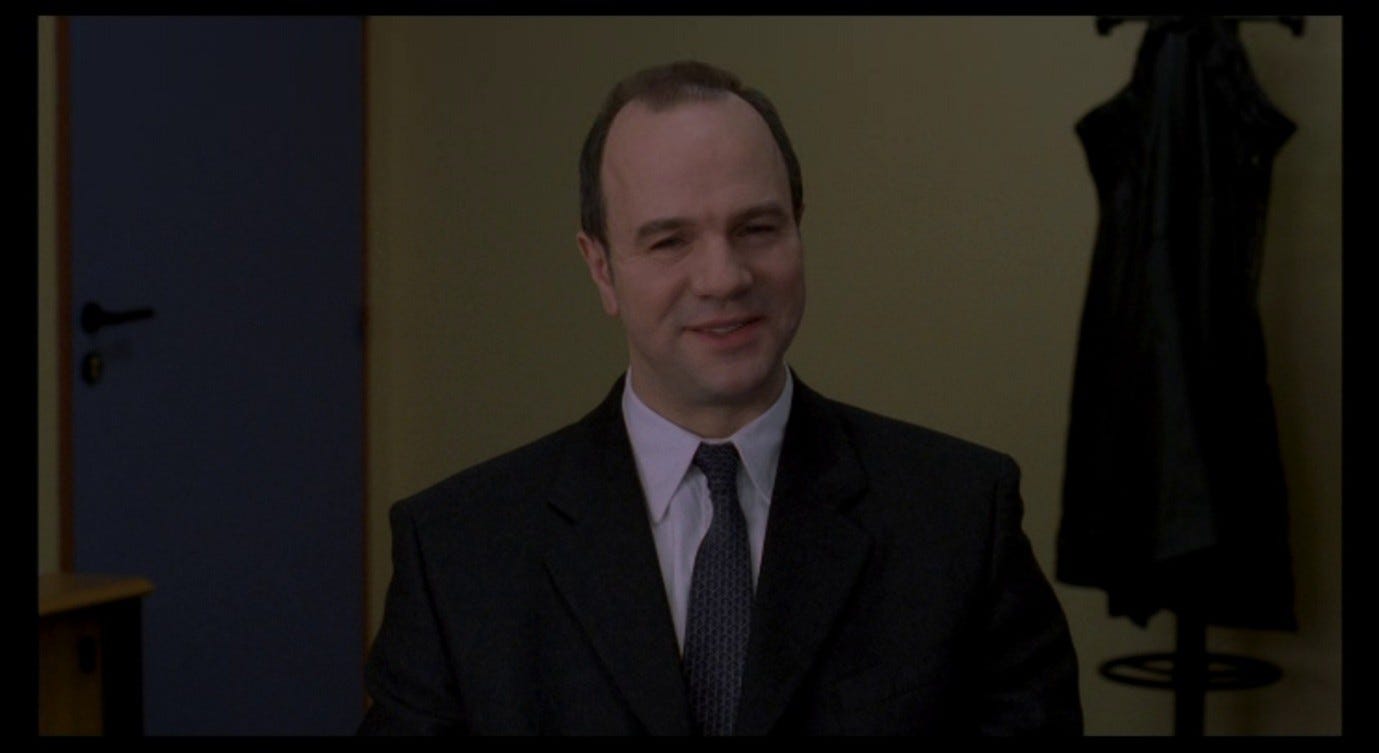

The final scene of Time Out makes use of a similarly ambiguous transition. In that film, Vincent, like Giuliana in the harbour, flees to a remote space far from his home, and disappears into the shadows. The moment feels like it could be the end of the story; we wonder for a moment whether Vincent is about to take his own life.

Then there is an abrupt cut to a daytime scene in which Vincent meets his new boss and discusses the responsibilities he is about to take on. We see his expression crumbling, in a way that might be invisible to his boss but is captured vividly by the camera as it dollies towards him.

Jocelyn Pook’s melancholy score reinforces our impression that Vincent’s illness has not been cured. But at the last second, just before the credits roll, he recovers his equanimity and asserts that he is not afraid of the new challenges he will face. The glare of panic in his eyes is still there, but less apparent than it was a moment ago.

We are left to wonder what the future holds for Vincent. Will he burn out again and suffer an even worse breakdown, or will he suppress his anxieties and be a good employee for the rest of his working life? Neither outcome would constitute a happy ending.

Red Desert perhaps reaches a more hopeful conclusion than Time Out. It may be that Giuliana’s hard-won existential wisdom, which she articulated in her speech to the Turkish sailor, will in fact serve her well and enable her to enjoy some measure of contentment. Perhaps, like Amelia at the end of The Babadook, she has learnt to control her illness, at least to the extent of being able to spend quality time with her son. In all three films, though, there is such a stark contrast between where we have just been and where we are now – between the darkness of Amelia’s basement and the lightness of her garden, between Vincent’s long walk into the night and his bright, cheerful induction meeting, between the harbour and the factory complex – that we would be surprised not to hear the low growl of the Babadook, not to see the despair behind Vincent’s eyes, or not to find Giuliana still alienated from her son, in those final moments (see Part 23 for further comparison of these three films).

These endings are truly ambiguous. They evoke the experience of chronic mental illness as a condition that feels insoluble and ‘incurable’. As Dar Williams puts it in her song, ‘After All’:

And when I chose to live,

There was no joy, it’s just a line I crossed.

I wasn’t worth the pain my death would cost,

So I was not lost or found.1

For Giuliana, her apparent recovery does not mean she has found a new type of joy, or even that she has learnt to derive pleasure from simple things like going for a walk with her son. She is not a donna sola, so she cannot simply be ‘lost’ (by taking her own life or leaving the country), but as we see in this final scene, she is not ‘found’ either. She is still suffering from a condition that only she is aware of, and while she seems to have re-inserted herself into reality, it is not clear how much it costs her to have crossed that line.

There is a moment in Edward Yang’s Yi Yi when a woman stands in her office looking out of the window, and the camera is directed at the window interior. We see Min-Min’s reflection in the glass, but she seems to float insubstantially against the dark city outside.

Then her colleagues arrive and turn the lights on, replacing a portion of the city-scape with the pale green surfaces of the office walls and furniture. Min-Min steps away from the window to talk to someone.

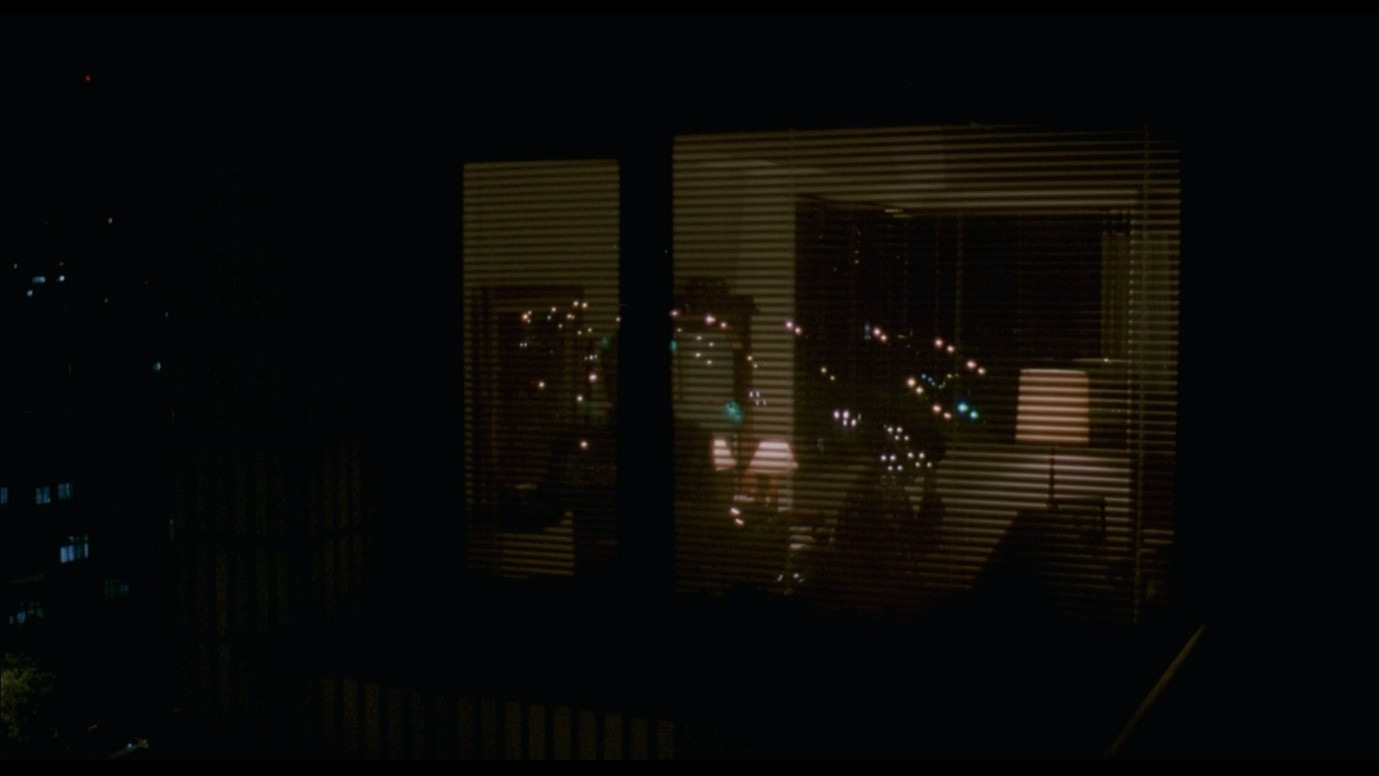

As the writer-director Edward Yang says on the commentary track, ‘Another perspective on reality just took shape right in front of our eyes.’2 Min-Min is pictured in one reality, as a ghost amongst the skyscrapers, then she is pictured in another reality, as an office-dweller gradually re-integrating herself amongst her colleagues; and strangely, the former reality felt more real. In the previous scene, we saw (from outside) Min-Min’s husband closing the blinds in their apartment, sealing them off from the world and replacing the transparent window with a dark mirror that reflects only the Alphaville-esque lights of the busy roads.

And in a later scene, we see another character alone in her hotel room, reflected in the window (which we look at from the inside) but rendered all but invisible amongst the interior shadows by the (already dimly lit) exterior.

All three shots juxtapose different planes of reality. These characters occupy one space in a literal sense, but emotionally they are elsewhere – more outside than inside, more like their reflection than they are like their physical self. Elsewhere on the commentary track, Yang notes that these images emerged organically from the film’s urban settings. As in PlayTime, transparent and/or reflective surfaces are ubiquitous features of the modern world. Antonioni uses such imagery too, especially in La notte: in Parts 5 and 14, I discussed the title sequence of that film, in which the camera descends the Pirelli building and finds Milan reflected and transformed in the windows.

Later, there is a highly disorienting shot in which we see Giovanni approaching Valentina. Which of them is reflected in the glass and which is seen through it? Even after many viewings, I have often guessed wrong. It is hard to orient ourselves in relation to such images: where are we, what are we looking at, and how are these characters (or people in general) positioned within this location, amongst these screens?

More commonly, however, Antonioni prompts such questions through a different kind of composition. As Giovanni enters the room and starts up a conversation with Valentina, the camera pans right, he walks out from behind the glass, and we realise that Valentina’s image was the reflected one. Now she is framed between two tree trunks.

If, at the beginning of this shot, there were multiple perspectives on reality, with Valentina flitting between them, by the end of the shot she seems trapped in a narrower, less playful space. Like Giovanni, we look at her and wonder what position she occupies in this mansion, how she sustains herself in a home that seems so oppressive.

In ‘The Dangerous Thread of Things’ – Antonioni’s segment of the portmanteau film Eros – we see a similar transition during the beachfront café scene. At first we look at the café from outside, through the window, and might think that the people in the glass are reflections, until they approach the window and we realise they are behind it.

The wide shot inside the café positions the window-frames so that the beach is largely invisible, and the woman on horseback almost seems to be travelling on water, like the ship that sails through the forest in Red Desert (see Part 18).

But as in that scene, the camera changes position to clarify the spatial relations. Ultimately the couple in ‘Dangerous Thread’ are seen at their table, glumly absorbed in their own feelings. The woman outside has tied her horse to a fence-post. The beach is now expansive and all-encompassing, while the ocean seems distant and ill-defined.

Later, the couple are seen bickering in an arbour: ‘I love this place,’ she says, ‘but with you it feels oppressive.’ Perhaps, when she is alone, the arbour gives her the same feeling of escape as that view from the café window, but with this man it becomes just like the café table, a space in which the oppressive constraints of her life become all too clear. The dappled sunlight inside the arbour, rather than connoting romance or magic, serves to obliterate the characters, merging them into the tangled vegetation.

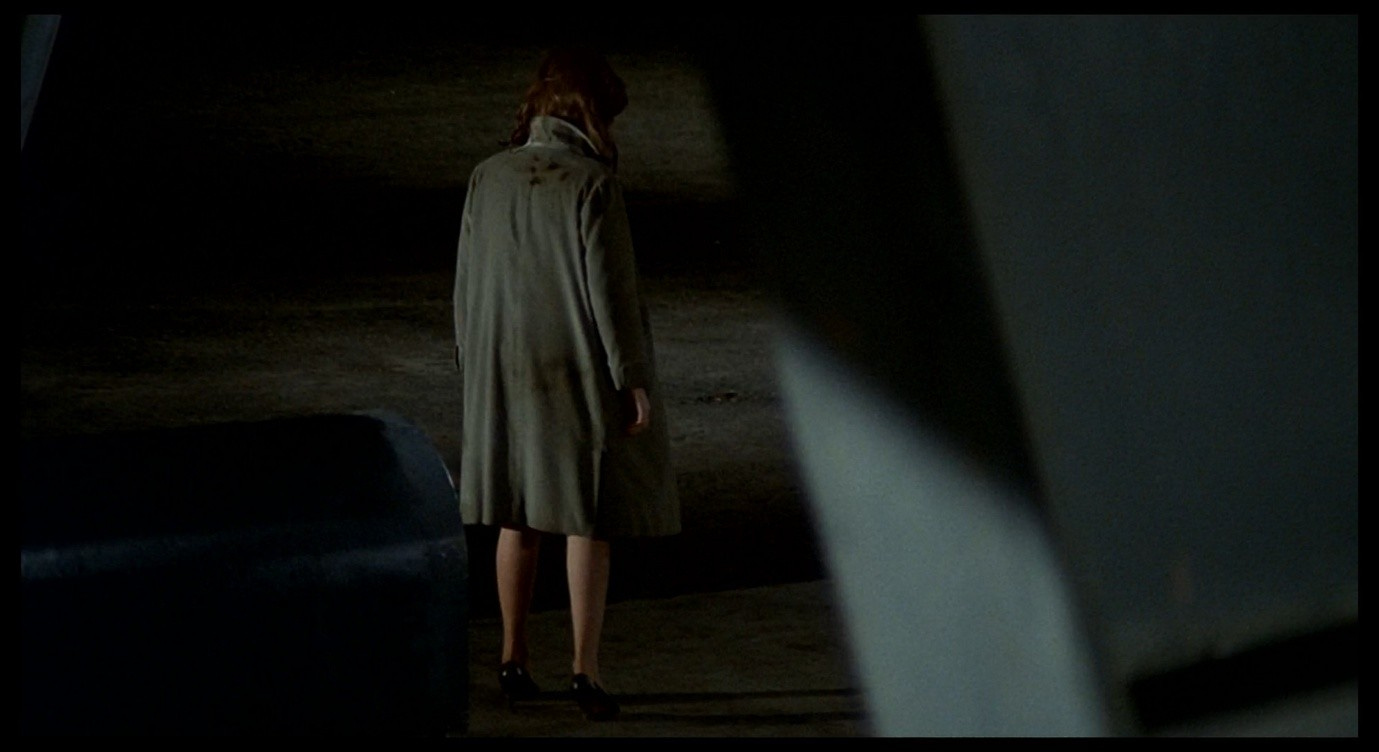

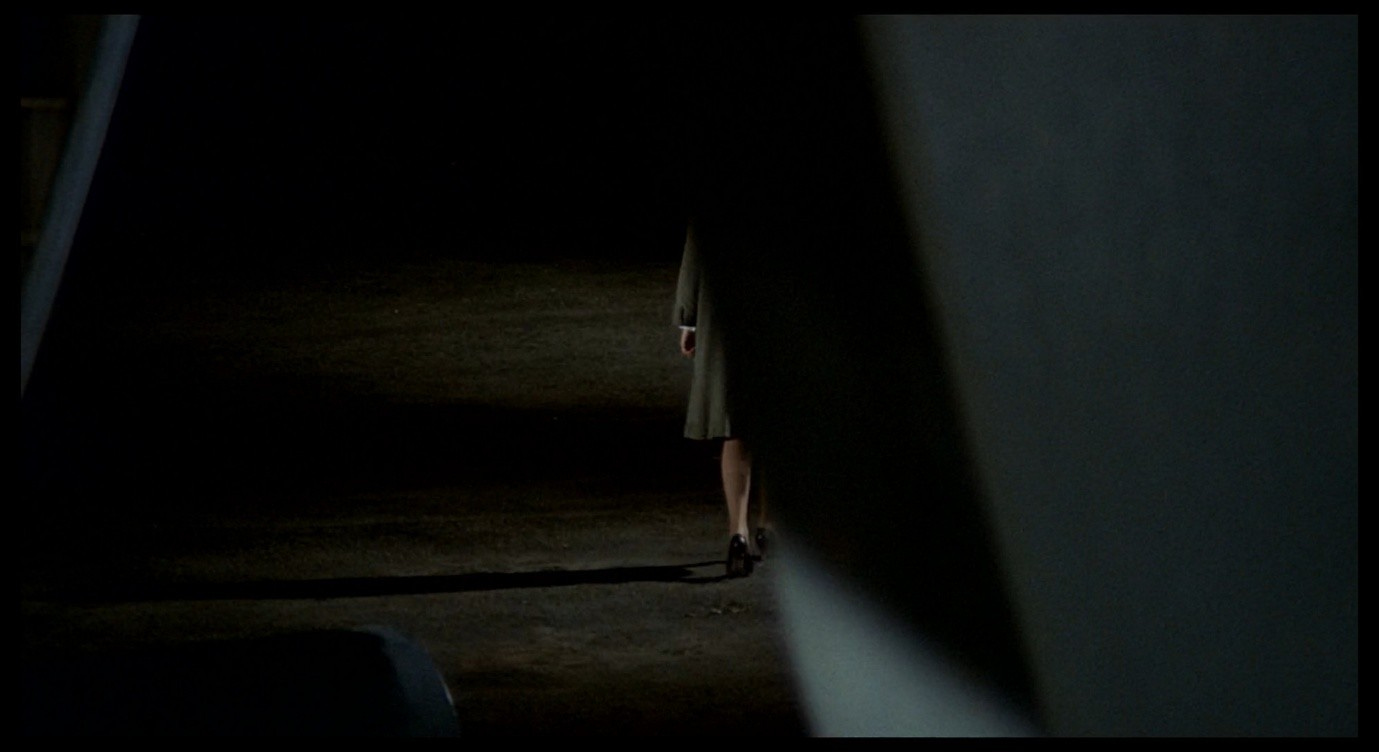

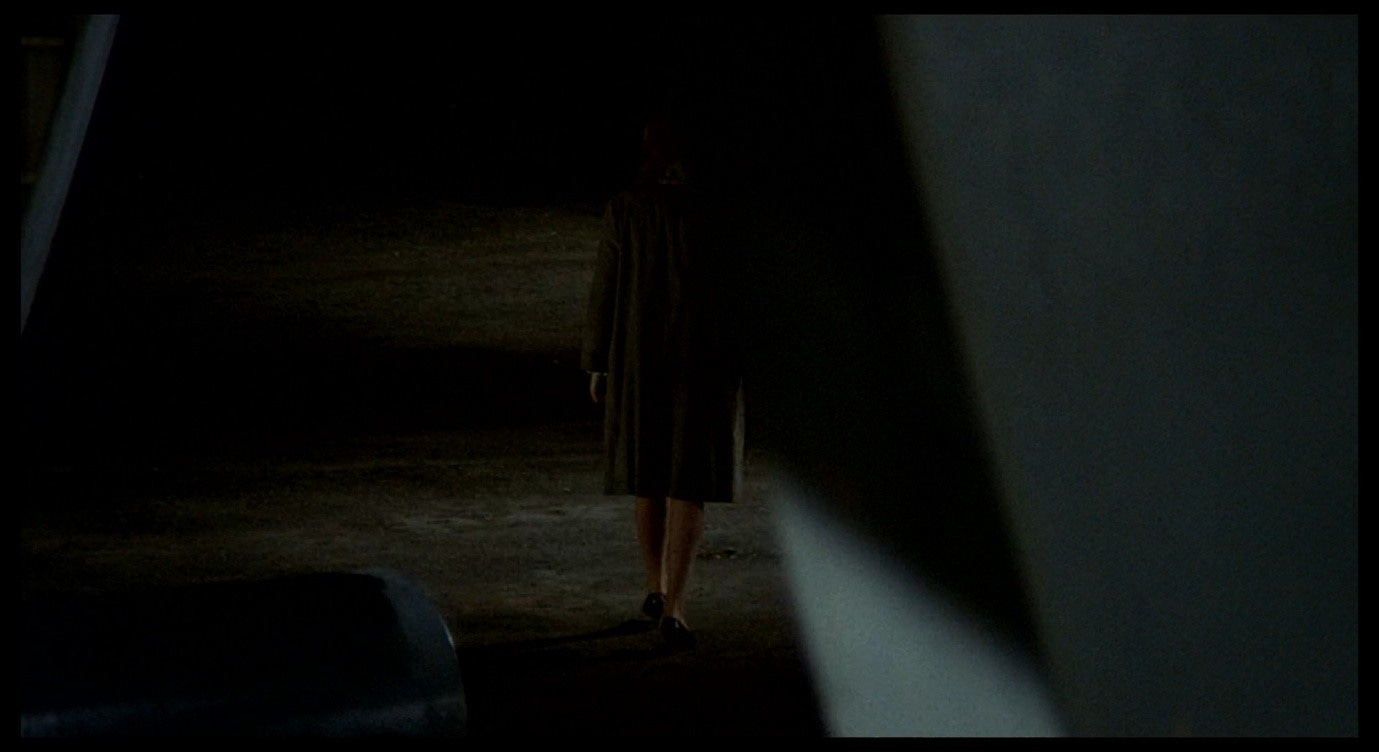

When we see Giuliana leaving the harbour in Red Desert, there are no reflective surfaces or tricks-of-the-light. Instead, the camera is positioned close to the loading mechanism, so that Giuliana appears trapped within a blurry grey triangular frame, then disappears into the frame itself.

The telephoto lens exacerbates the feeling of claustrophobia, transforming the relatively open, sprawling space of the harbour into a small, constrained one. It is a subtly different effect from the wide-angle shot in La notte that shows Lidia dwarfed by a huge wall, emerging briefly from behind it only to disappear again seconds later.

Lidia is made small by the vastness of the structure that towers over her, whereas Giuliana (who takes up more space in the frame) is made small by the smallness of the space she occupies. We see Lidia from space and Giuliana through a microscope. Some Antonioni characters traverse their environment with ease but feel detached from it; some struggle to exist in (let alone navigate) their environment but feel inextricably attached to or merged with it. Lidia is removed from reality, Giuliana is inserted into it.

Kijū Yoshida, who was deeply influenced by Antonioni, resorts almost compulsively to these reality-reconfiguring compositions. In one pair of shots from Eros + Massacre, we see both kinds of effect discussed above. First, Itsuko walks down a corridor beside a glass pane that both reflects her and makes visible the shadowy room behind it.

Then, Itsuko enters a wide-open and glaringly white space, but is inserted (by the eccentric positioning of the camera) between two stairways leading in opposite directions.

In both shots, Itsuko looks into the camera lens. She is a historical figure in a film that re-enacts true events, but Yoshida also foregrounds the artifice of these recreations. Eiko, the present-day investigator who is trying (in 1969) to unearth this story from 1923, is told to give up her research, to stop trying to reconstruct a past reality she cannot hope to understand. The image in this moment is blurry and distorted, as though the film itself were a decayed relic from a now-irretrievable past.

But Eiko responds by positioning herself against a screen on which photos of the 1923 earthquake are projected. Now they are projected onto her and she is part of them, but she is also a three-dimensional reminder of their two-dimensional artifice. When the pictures run out, she stands against a white background, eyes wide open but looking only at the light that illuminates her.

In the very next scene, one of Eiko’s research subjects – Noe Itō, the one she is most interested in – turns up in 1969, and Eiko frantically tries to interview her before she recedes into obscurity.

In one sense, the film is about the impossibility of knowing or representing reality. Everything that happens is incomprehensible even in the moment when it happens, and becomes still hazier with the passage of time. But Eiko’s project is not completely futile: it is a creative act and she is an artist, engaged in a complex dialogue with reality. That disorienting high-angle shot of Itsuko, who was made small between the mirrored stairways, reflects something of Eiko’s approach to historical fact.

The character we see in that shot is deciding on a course of action, and later we will see three different versions of a famous incident in her life, none privileged over the others, all presented as though they reflect some aspect of reality. The same principle applies to Yoshida’s disorienting compositions. Within a single scene, he will put the camera in drastically different places in order to show the malleability of this world and of the characters’ relations with it. Itsuko and her reflection, Noe and the version of her left to posterity, the real person and the film character, the character and the actor – we are constantly asked to see with a kind of double vision, engaging with both perspectives at once. How Itsuko perceives herself and her actions may differ from how we see her in re-telling (cinematically) her story, or that bizarre composition may capture her feelings more accurately than a conventional shot/reverse-shot of the conversation would have done, or this version of her may bear no resemblance to the real person (who was called Ichiko, and who did not like this film) but still express something meaningful.

Telling a story, whether in writing or through images, means positing a version of reality – ‘What if it were like this?’ – and inserting people into it. To emphasise the ‘what if,’ as Yoshida does, keeps us aware that this is only a version of reality, just as Yang’s play with light and windows reminds us that what we see through transparent glass – whether through a window or a camera lens – is only the reality that has been opened up or closed down by these lights, these blinds, this framing, and this choice of lens. When Antoine, in Nausea, said that his surroundings did not seem real, or that an unreal fog was seeping from them, he was waking up to this same sense of contingency (see Part 49). Looked at from certain angles, the walls we live inside start to look like cardboard, as though they could fall away and leave us stranded in an unknown place.

The doctors in the clinic have told Giuliana to reinsert herself in reality, to get over this Sartrean nausea and accept herself and her environment. When she says, ‘Everything that happens to me is my life,’ this represents a kind of reconciliation with reality. It is not a case of ‘What if it were like this?’ but of ‘This is it.’ Again, this is a very characteristic direction of travel for Antonioni. We feel, with a mixture of excitement and terror, that there must be realities beneath this one, deeper layers that could be unveiled, if not to our own eyes then to the camera-eye that has all the resources of every art-form at its disposal. But we tend towards the conclusion that these other realities are not photographable, and that the closest we can get is an image or sequence of images that communicates how limited our perspective is.

There is so little to see in that shot of Giuliana leaving the harbour. So much of the frame is occupied by the frame-within-the-frame, and what is left seems so empty and dark. There are no new perspectives on reality to be opened up here, no playful interaction between truth and fiction, just a benighted, hemmed-in patch of ground.

Coming as it does immediately after Giuliana’s speech, this image sums up the ‘everything’ that is her life, insisting on the reductiveness and bathos of that conclusion. Everything does not amount to much. When Giuliana has vacated this bare space, we cut to the wide shot of the factory towers.

Together, these two images suggest what it means for her to be reinserted in reality. It means accepting the constrained, oppressive perspective of the first shot, the obscure frame around it, and the dark patch of ground she occupies; then it means returning to the wide-open clarity of the second shot. In the title sequence, these factories seemed like metaphors. Blurred into near-oblivion, they were hard to distinguish from the umbrella pines, just as the various layers of the soundtrack were hard to categorise as robot or human voices, as industrial drones or musical notes. There was a promise and an opportunity in those nebulous sounds and images. They seemed to ask, ‘What is reality?’ The first shot of Red Desert’s final scene says, ‘This is reality.’ Focus has been restored, showing us Giuliana’s life and environment as they really are, shutting down that sense of promise and opportunity.

This is, however, not the end of the story, nor is it the only meaning contained in the wide shot of the factories. Angelo Restivo’s analysis of the title sequence reminds us of something important:

we are presented with a visual field completely out of focus, fuzzy shapes and colors whose objects are completely undifferentiated. This, we could say, is the gaze in the process of its emergence; this is Antonioni’s answer to the fundamental problematic of neorealism, the relation of the seen to the unseen, of the object to the subject. For insofar as neorealism grounded itself in the phenomenologists’ battle cry, ‘To the things themselves!’ Lacan’s reply is, ‘Beyond appearance there is not the Thing-in-itself, there is the gaze.’3

We might think again of Europa ’51, and of Irene confronting the ‘things themselves’ – the factories and the physical toll they take on human bodies – whereas Giuliana is absorbed in her own distorting-but-revealing gaze, her way of seeing that remains unseen by others.

As a counterpoint to Restivo’s argument, we could say that the final scene of Red Desert returns us ‘to the things themselves,’ deploying them as a kind of rebuke to that un-focused gaze that dominated the title sequence. In her reading of Giuliana’s final speech, Elena Past makes a case for the importance of the literal reality of industrial Ravenna:

[Giuliana] enunciates a contradiction. Bodies are separate, and her body intersects with that of the sailor, of the rusty ship, of the world at large. This incongruity recognizes both the integrity of the human actor and her entanglement in a nonhuman universe of things. […] Irreducible to her surroundings, Giuliana is yet of these surroundings. Both of her ‘epidermic’ epiphanies are true: ‘Now you are part of me – part of what is around me, that is’; and ‘bodies are separate.’ […] Cinema can offer an ethical alternative to the celebratory or unilateral logic of petrochemical progress, although it must also admit its entanglement with industry. As we watch Red Desert decades after its production, we, too, can see with Giuliana that our bodies are separate, even as we say, with the film, the factories and their toxic emissions, the pine forests, and the eels with petroleum in their bellies, ‘You are part of me.’4

I think the un-focused and focused images of the factories, at the beginning and end of the film, contain something of the ‘part of me’ sentiment that Past describes. Red Desert cannot reject the ‘things themselves’ because its existence, as an industrial product, depends on them. But it is not solely beholden to that worldview that says, ‘This is reality,’ and in its final moments it will return to those fuzzy images and unearthly sounds with which it began. They are part of this world too. Giuliana is reinserted in reality: the frame closes in on her, the surrounding structures reassert themselves. By the same token, she reasserts her place among them, and says, ‘I am part of you.’ Her so-called neurotic gaze, which – the film asks us to concede – makes the ‘things themselves’ appear otherwise than they are, also defies this unilateral logic and says, ‘My life is everything that happens to me.’ Giuliana does not take her own life, nor does she leave on the Turkish ship. She must admit her entanglement with reality, so it must admit its entanglement with her.

Next: Part 51, Our place in the red desert.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Williams, Dar, ‘After All’, The Green World (Razor & Tie, 2000)

Yang, Edward, and Tony Rayns, Commentary track, Yi Yi (Blu-Ray, Criterion Collection 2017)

Restivo, Angelo, The Cinema of Economic Miracles: Visuality and Modernization in the Italian Art Film (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), pp. 139-140

Past, Elena, Italian Ecocinema: Beyond the Human (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), pp. 46-47, 51