Everything That Happens in Red Desert (39)

What is Giuliana afraid of?

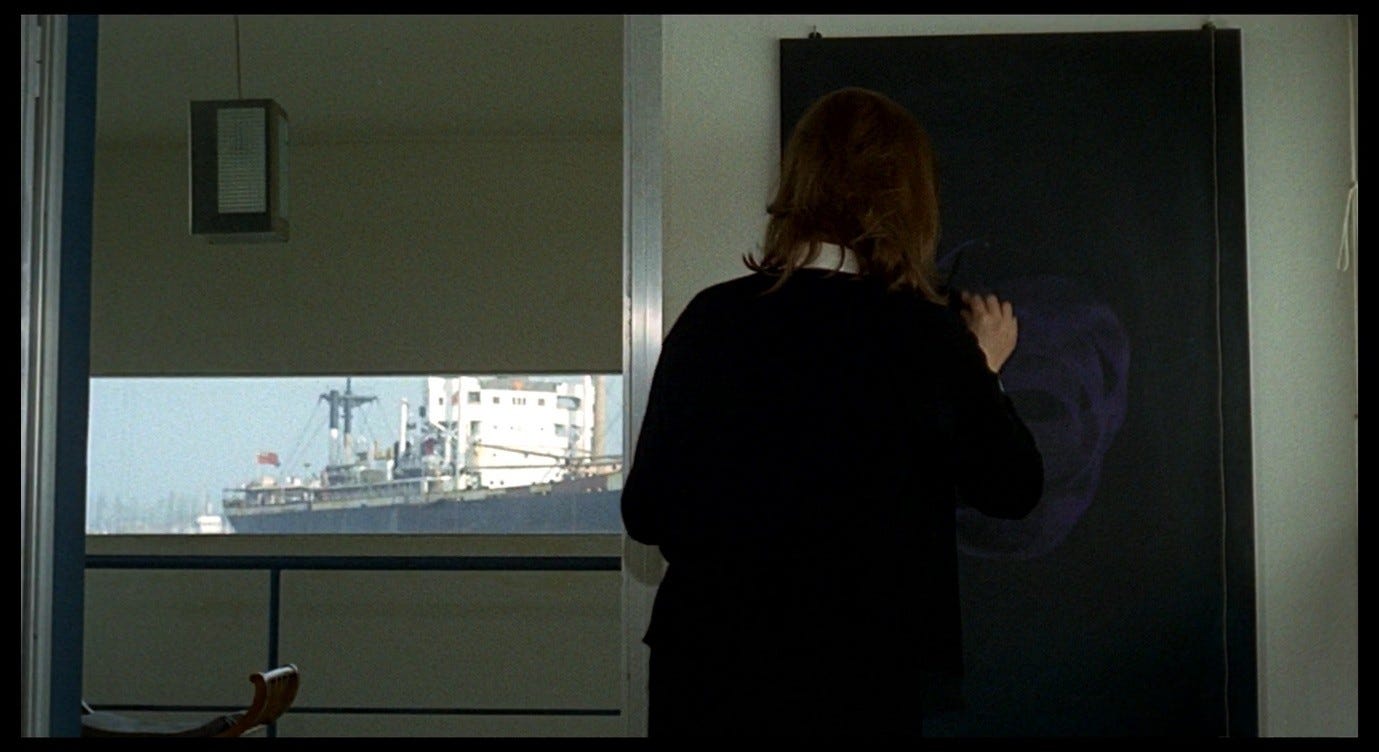

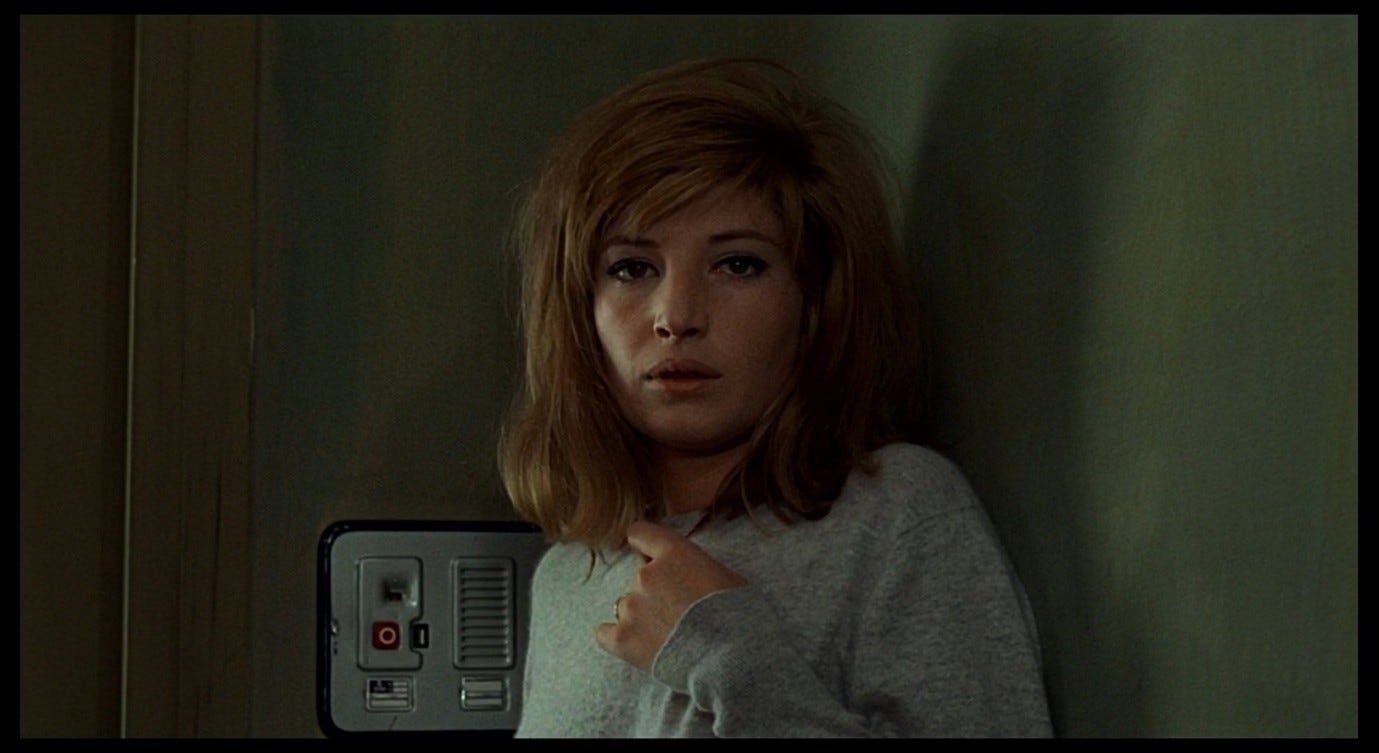

After Corrado’s initial attempt at love-making – stroking Giuliana’s hair while she looks at the map – Giuliana moves away from him, anxiously takes off her cardigan, and sits on the edge of the bed.

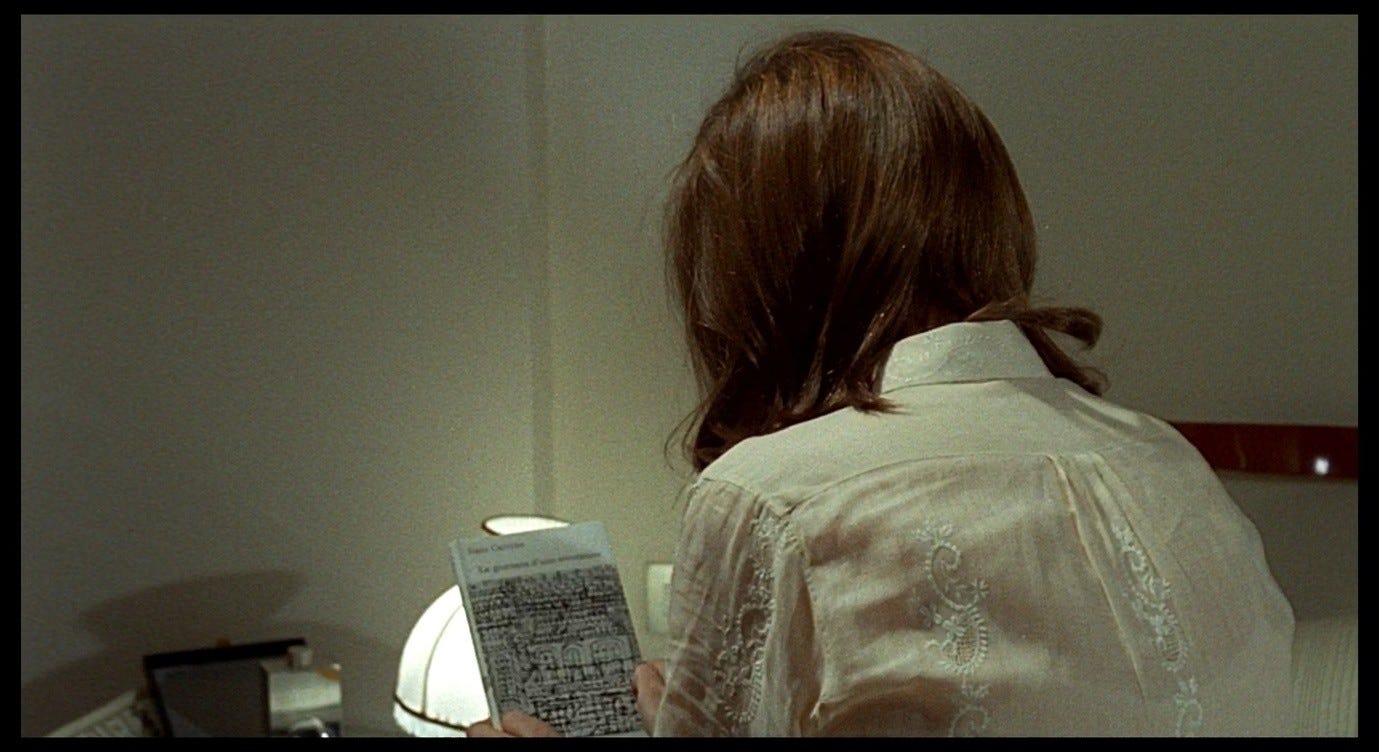

After glancing at a book, Italo Calvino’s The Watcher, she turns and asks Corrado when he is leaving. ‘I don’t know,’ he says, as we cut to an intense close-up of Giuliana looking distressed, and (we would assume) looking at Corrado.

But when we cut to the reverse-shot, we slowly realise that she is looking past Corrado, at the wall. He realises this as well, and asks what she is looking at. ‘There,’ she says as the electronic hum builds menacingly on the soundtrack.

It is like the moment in a ghost story when one character sees something that another cannot. For now, we see as Corrado does, but as the scene progresses we will be shown these phantoms from Giuliana’s perspective, insofar as this is possible. The seemingly disjointed events just described – Corrado’s amorous gesture, her movement away from him and her question about his departure, the momentary foregrounding of Calvino’s novel, and Giuliana’s sighting of the invisible entity on the wall – are in fact closely intertwined. The way she is touched and watched by Corrado, and his way of being here but also already gone (to South America or simply to a state of dissociation), have something to do with the way in which Giuliana’s fears are externalised in this scene.

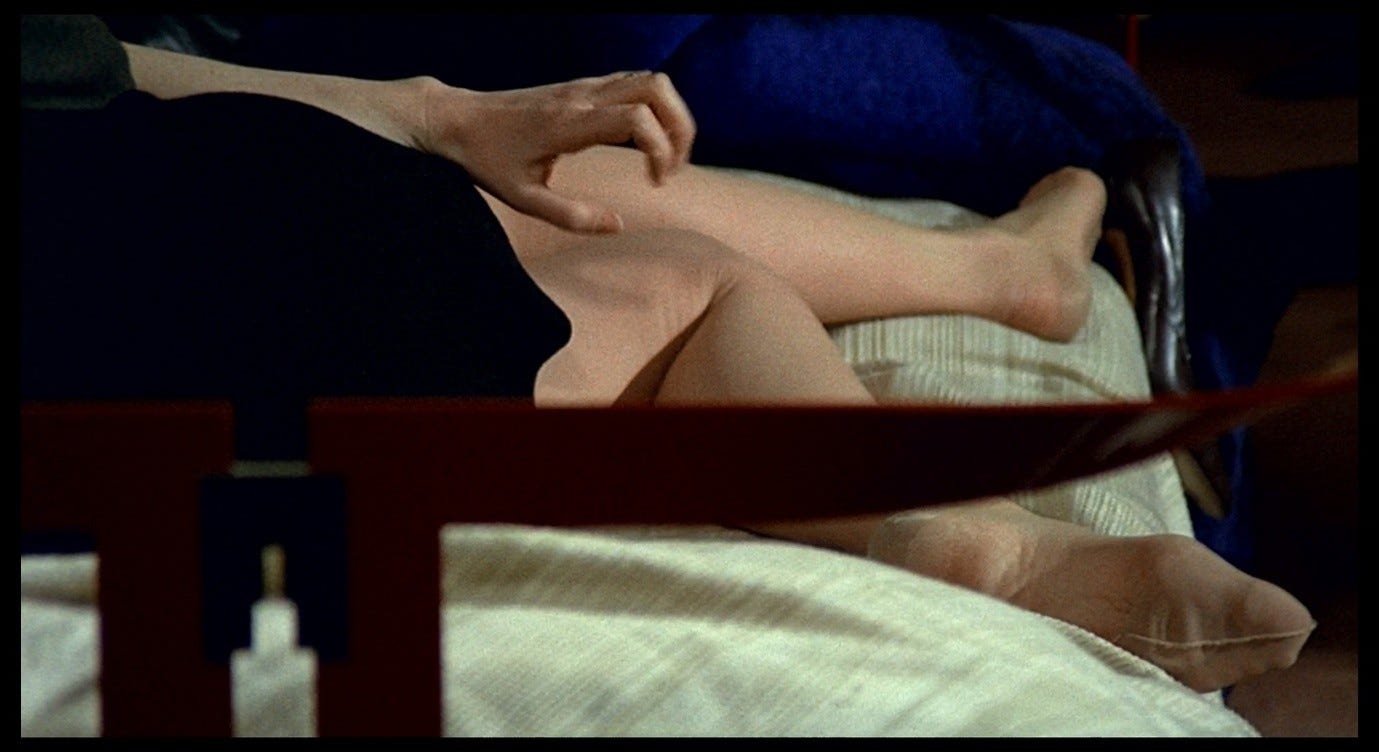

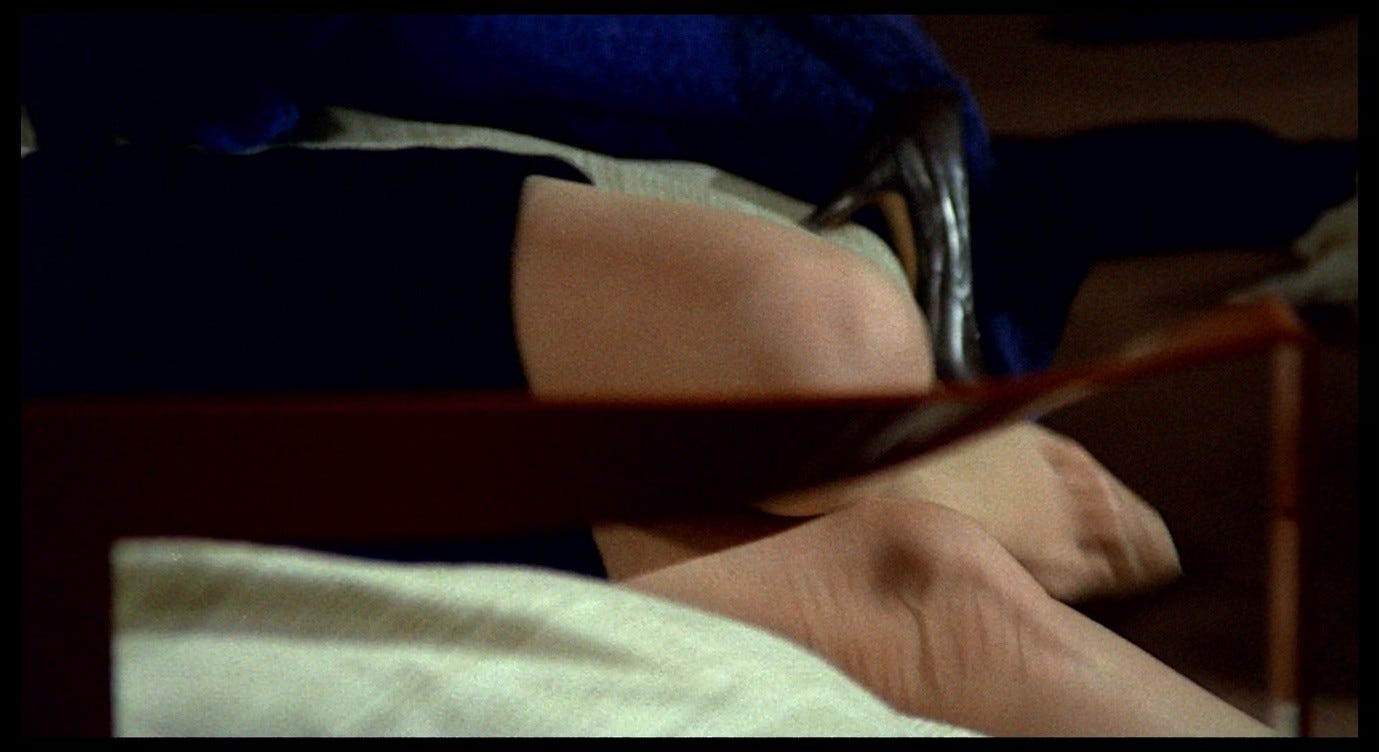

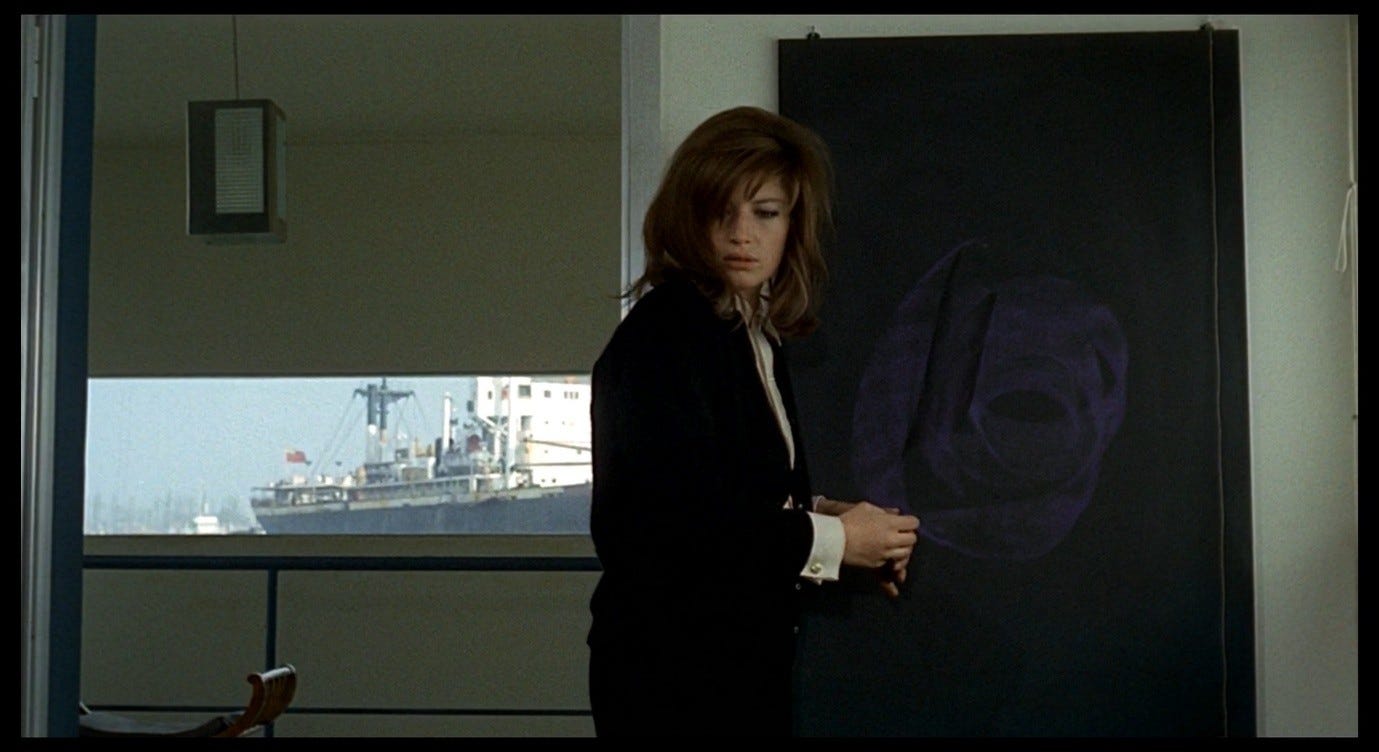

When we see nothing on the wall, this initial privileging of Corrado’s gaze is important because when Giuliana says ‘there,’ Corrado does not look back at the wall. Instead, as if in response to (but also in defiance of) Giuliana’s gesture, the camera cuts to the ‘there’ that Corrado is looking at: her legs extended across the bed.

What makes the edit even more confusing is that when we see Corrado he appears to be looking at Giuliana’s face, but when we cut to his perspective we only see her legs. She indicates the wall; but he looks at her; and he really just sees her as a sexual object. As the screenplay says, when he sees her lying beneath him, ‘the temptation to touch her is extremely strong.’1 The two characters’ eyelines are at cross-purposes, but there is also a causal relation between them. Giuliana’s anxiety, restlessness, and claustrophobia are on one level a response to Corrado’s attentions (and lack of attention), and the thing she sees ‘there’ on the wall is on one level a manifestation of how she feels about Corrado looking ‘there’ at her legs.

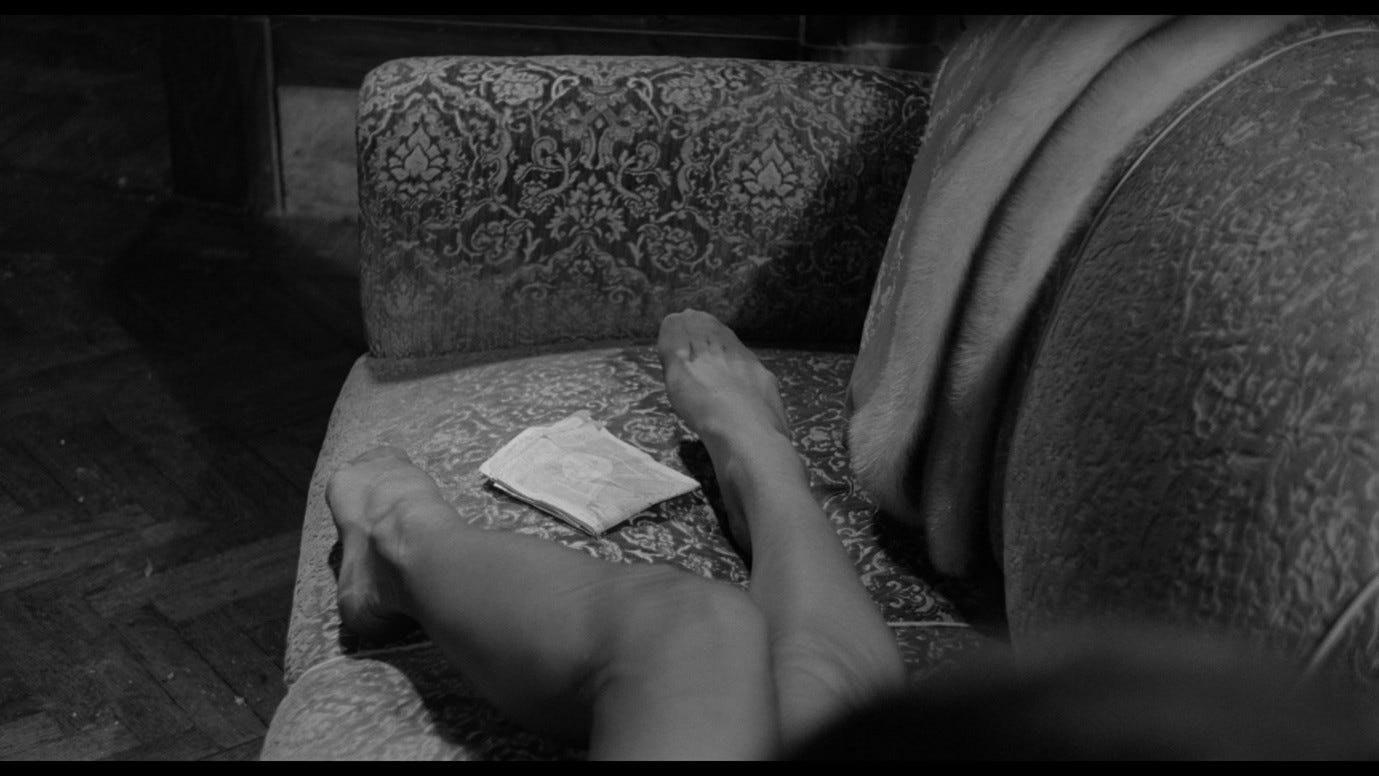

The problem here is not ‘sex’ as such, any more than in the night-terrors sequence when Giuliana resisted Ugo’s attempts at love-making. She felt sincerely amorous and liberated in Max’s shack, and was frustrated at the impossibility of making love to her husband while other people were around. The problem is the malattia dei sentimenti from which so many of Antonioni’s characters suffer, and which causes them (especially the men) to express their erotic impulses in violent, dysfunctional ways. The clearest example is Sandro in L’avventura, forcing himself on Claudia, having rejected her affections in the previous scene as a way of avoiding his real problems (see Part 11), and later paying Gloria Perkins for sex in the midst of another bout of self-loathing. Gloria is last seen as a pair of legs clutching the bank-notes Sandro has thrown at her, an image which could be taken as expressing misogynistic contempt for Gloria (on the part of the film-maker), and/or as reflecting Sandro’s conception of her and of all the women in his life; she is just a pair of legs, interchangeable with any other pair of legs.

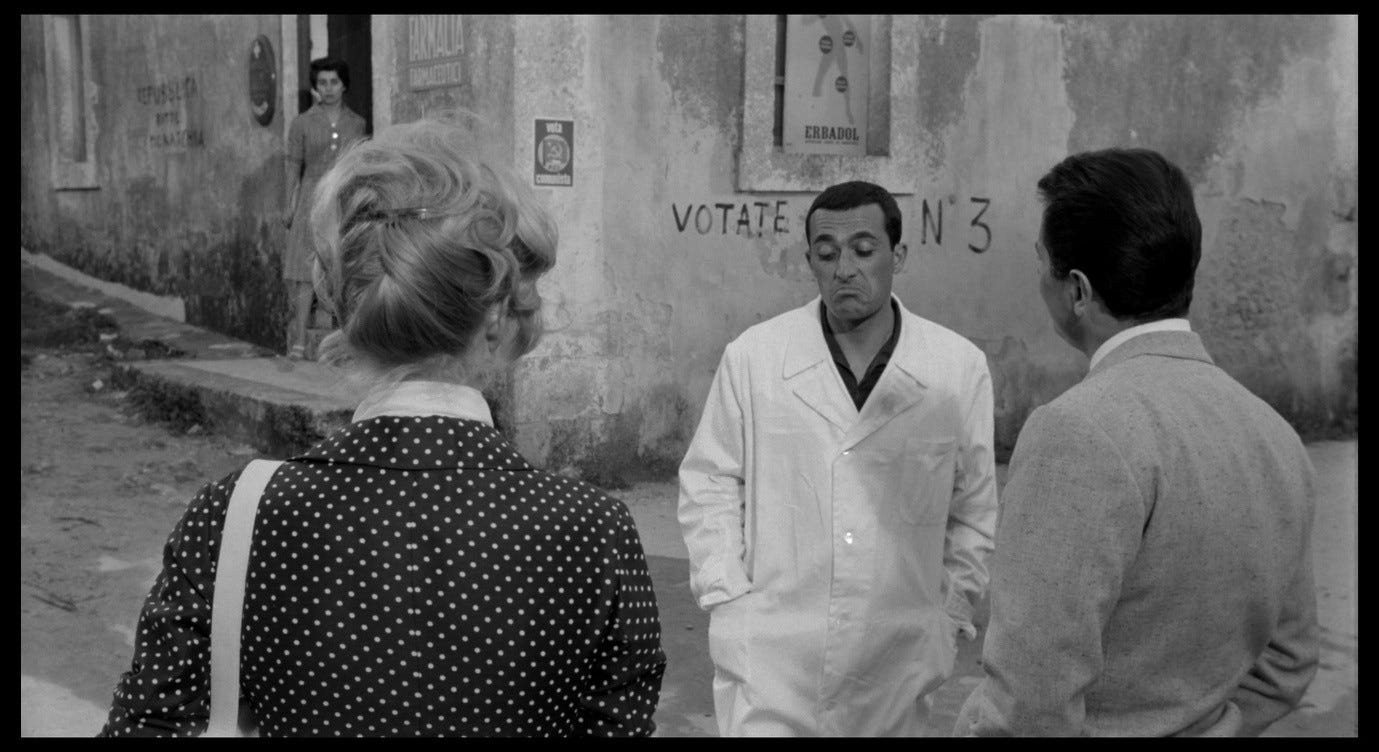

Earlier in L’avventura, Raimondo ducked under a table to ogle Patrizia’s legs, and the unhappy pharmacist in Troina described Anna (if it was her) concisely with the words, ‘Beautiful girl, beautiful legs!’, glancing down at Claudia’s legs as he said this.

So this leg fixation might be taken as a kind of short-hand for male lust. William Arrowsmith sees the ‘elimination of the individual’ as one of the main causes and symptoms of ‘sick Eros’ in Antonioni’s films:

Demoted to anonymity, deprived of individual and individuating features, the erotic ‘other’ becomes […] merely a collection of discrete sexual fragments – those parts of the body, especially the legs, which are everywhere, obsessively, being looked at, stared at – fragments incapable of cohering into a distinct individual.2

In the red-room sequence in Red Desert, Giuliana was visibly disturbed at the sight of Max stroking Mili’s leg.

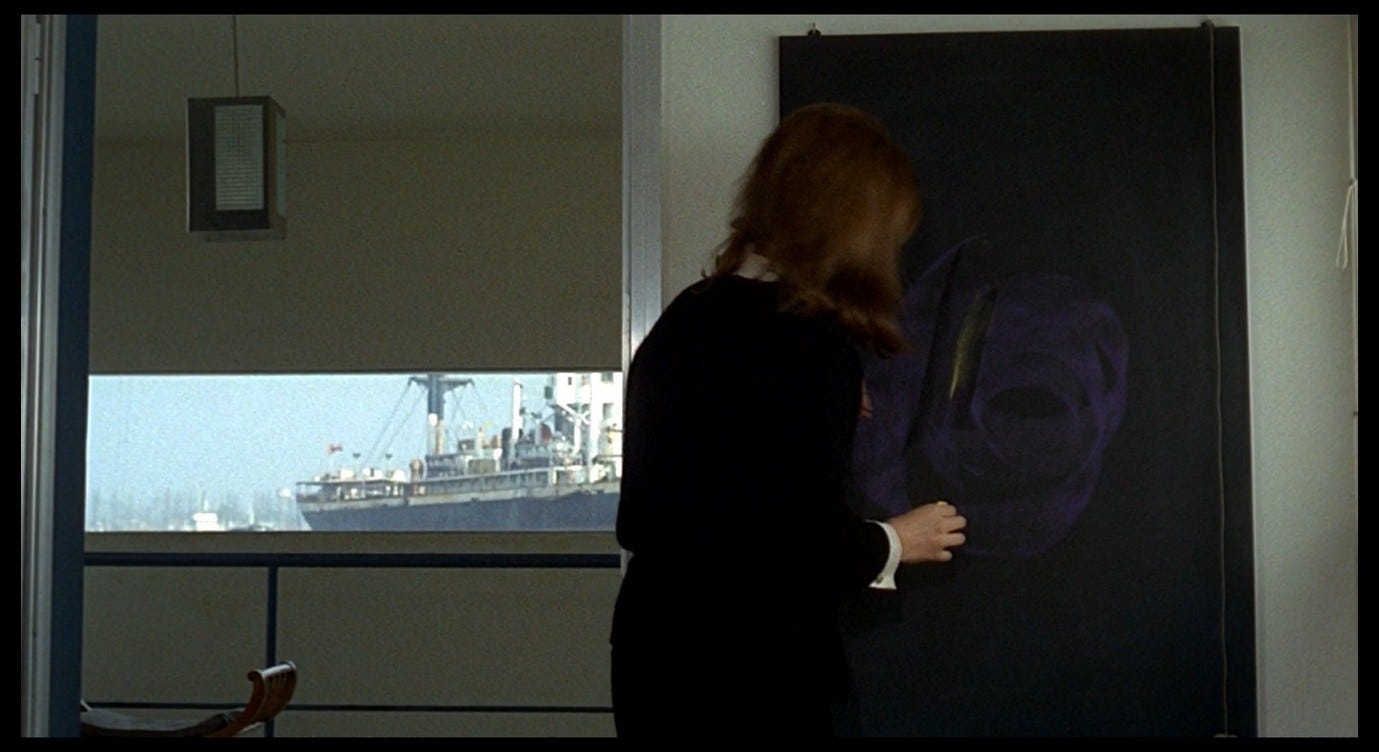

Now, in the hotel room with Corrado, her own legs will be repeatedly isolated, separated from the rest of her body, by the camera. Later, we will see an echo of the Gloria Perkins shot as Giuliana’s writhing legs cause her shoes to come off and almost fall from the bed.

We will also see Giuliana’s transparent tights wrinkling as she moves her legs.

Because the tights are transparent, we may think for a moment that we are looking at bare flesh, resulting in an uncanny effect: it looks like Giuliana’s flesh is rippling, as though she were literally dissolving into a liquid state (as she feared she would do if she looked at the sea too long). The rippling effect recalls the rippling surf in those layered images from the pink-beach sequence, where the action of the wave disrupted the boundaries between different elements of the natural world. In this case, Corrado’s sexual objectification of Giuliana clearly has something to do with these disturbances in the fabric of reality.

The shot of Giuliana’s legs pans right to show the rest of her, and we see that she is looking up at the ceiling.

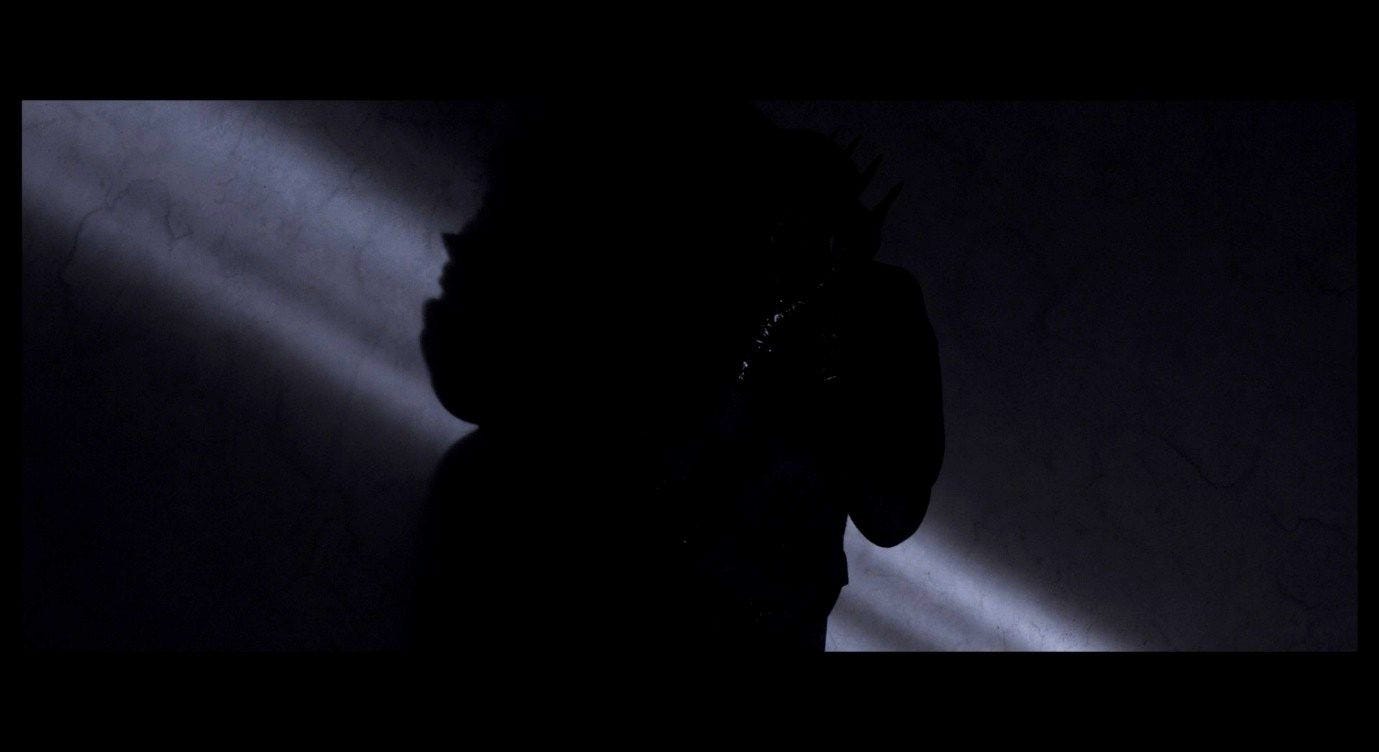

A shot of Corrado looking down at her reminds us that he is still there, regarding her with the same objectifying gaze. We see his eyes rove towards the foot of the bed, emphasising again that he is not looking at Giuliana’s upper body.

Our gaze, however, switches to a medium close-up of Giuliana’s face, and then to a shot from behind her head, representing her perspective.

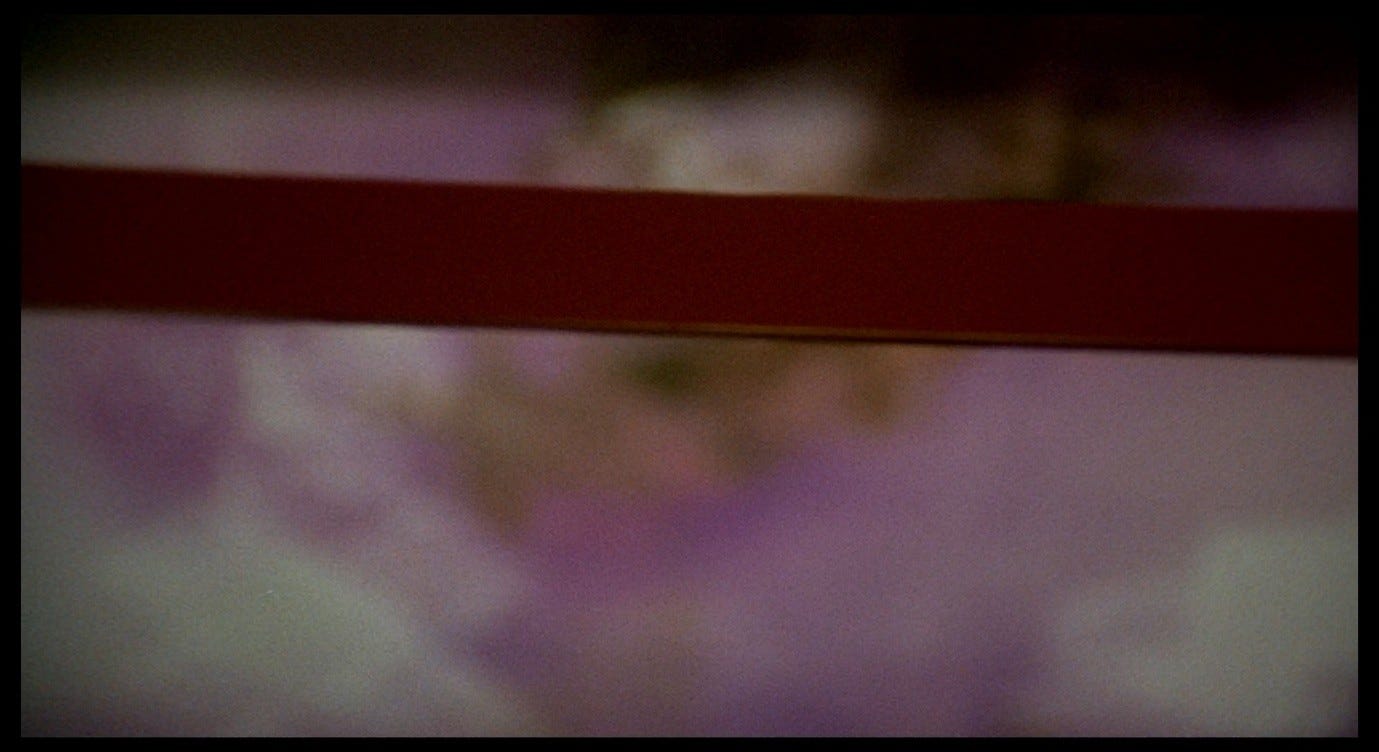

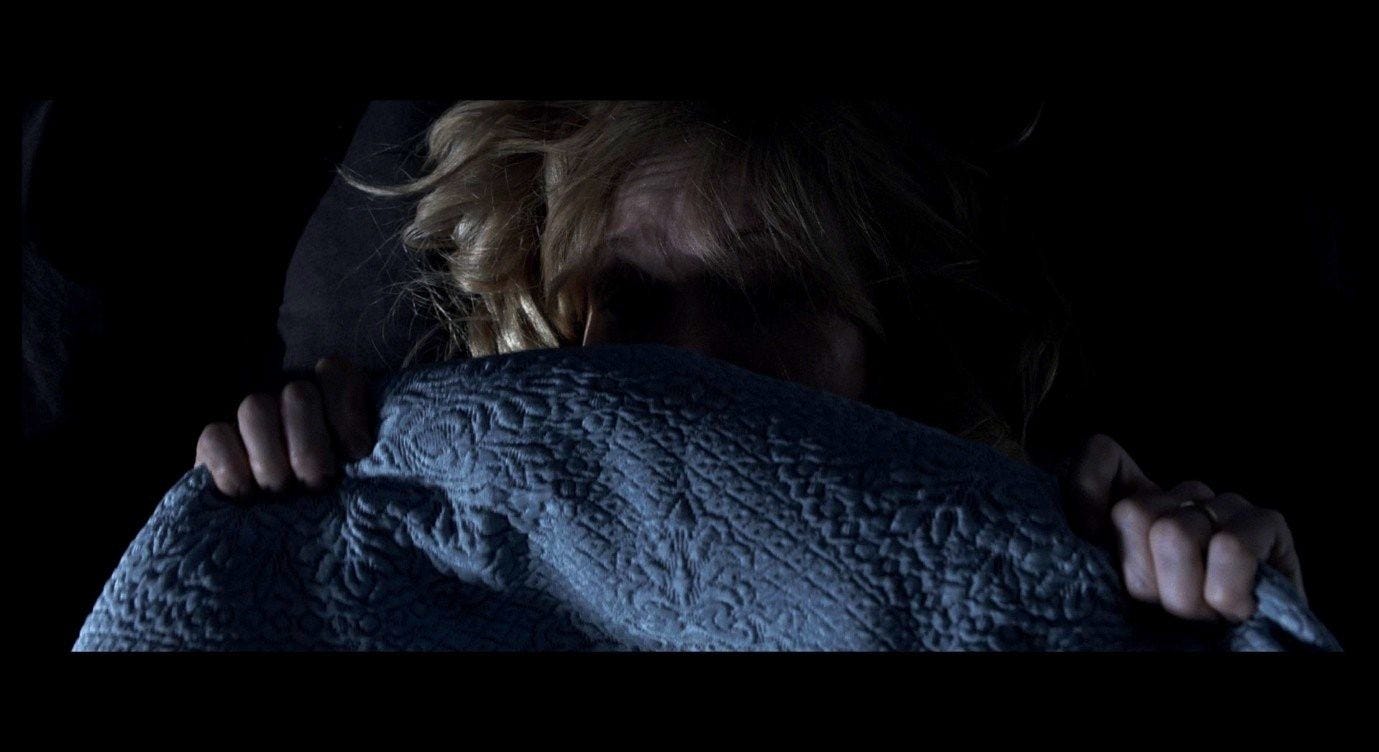

We share the hallucinatory vision she experiences, in a format that should be familiar to us by now: the back of Giuliana’s head is in focus in the foreground, while what she sees remains out of focus, as when she looked at the crowds of striking workers or at her companions in Max’s shack. The camera moves, and I think Giuliana’s head and the pillow it rests on are also being moved in front of the camera.

Rather than a simple panning shot, this feels like a significant shifting of perspective. The world revolves around us and we are revolving within it. We find ourselves adopting an impossible vantage point. There is no room for the camera behind the bed, so we become (if only unconsciously) aware that the film-set is being manipulated and re-presented to us in order to portray Giuliana’s subjective sense of her surroundings.

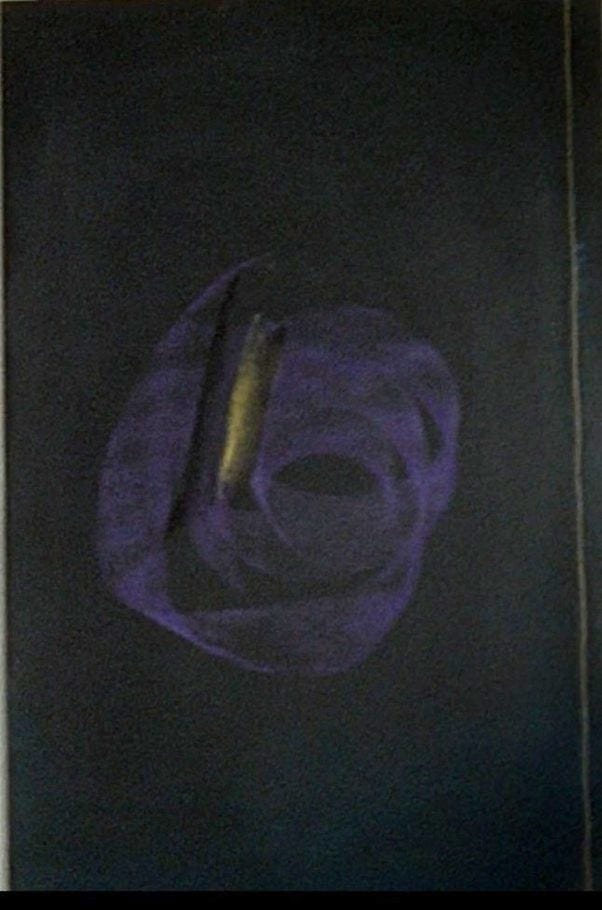

It is a fitting moment to begin doing this, because as Giuliana and the camera look to the right, and then upwards, we see a blurry image on the ceiling that cannot ‘really’ be there. It begins as a purple stain extending from the right-hand side. As the camera pans and Giuliana’s head turns in that direction we see more of the purple stain, and see a black blot at its centre.

Then, as the camera tilts upwards, we see that the shape extends even further. It is predominantly purple, but again we see a blackness spreading through it, seemingly looming down from the upper part of the frame. There is also some blank space near the centre of this upper part of the ceiling-stain, where the beige of the ceiling comes through, and around that there are faint streaks of yellow.

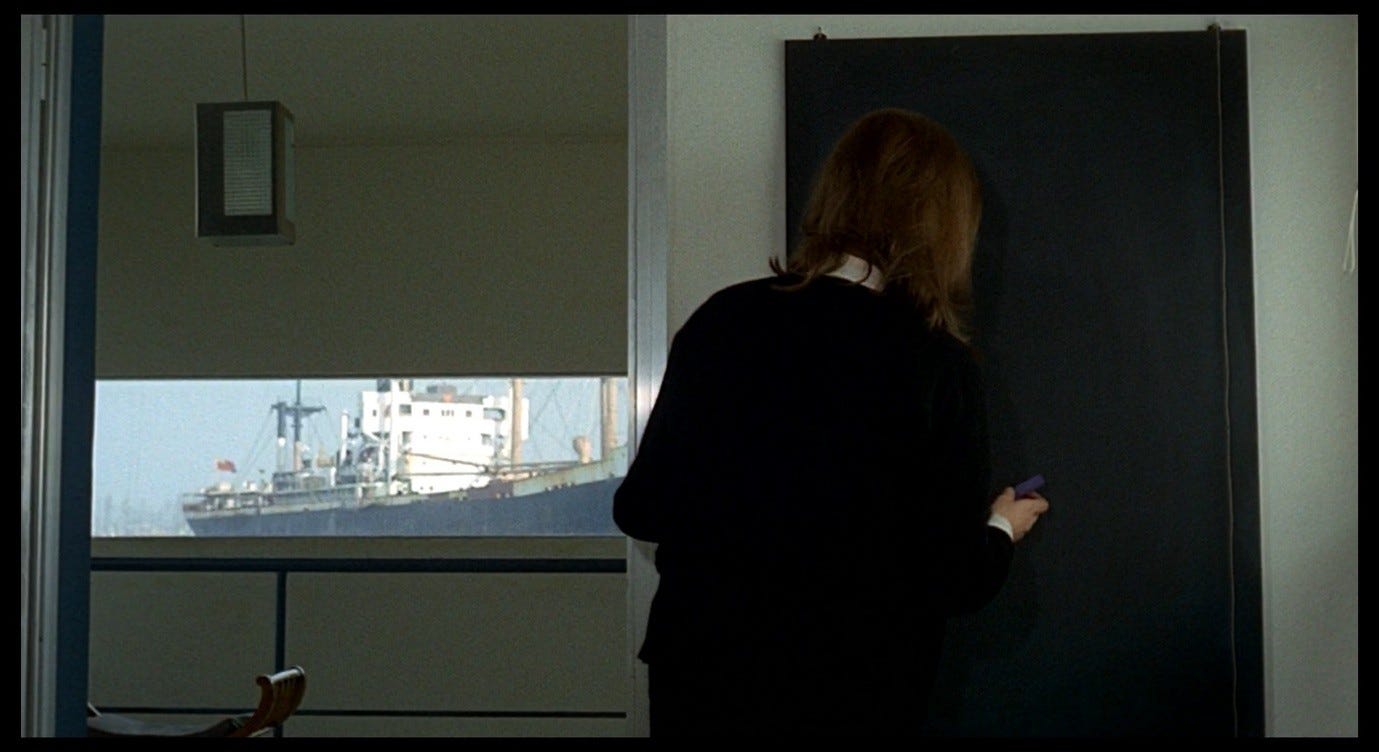

The stain is reminiscent of Giuliana’s chalk-drawing on Valerio’s blackboard, which was a swirl of purple with black and yellow streaks at its centre. As she left Valerio in the previous scene, a blurred close-up of that chalk-drawing filled the frame.

Because this image marked the transition from her home to the outside world, it created a sense that she was both running away from the purple-yellow shape and plunging into it as she ventured outside. One of the most interesting things about that chalk-drawing is the way in which it is drawn. Giuliana is trying to fulfil Valerio’s request for a new picture, so she begins by creating the purple spiral.

Then she uses an eraser to create a black gash in the top-left of the spiral.

Finally, she applies the yellow chalk, following the same line as she did with the eraser – and she makes a second yellow stroke before abandoning the drawing and attending to Valerio’s new request.

Like the story she then tells, the drawing feels like the product of an exhausted, distracted mind. The story, as I have argued, is a free-associating journey through Giuliana’s desires and fears, picturing a seemingly idyllic refuge from the environment that plagues her, but then deconstructing and dissolving that refuge, turning the dream into a kind of nightmare. The drawing, too, feels like an attempt at cathartic self-expression through art that turns against Giuliana. Her unconscious is momentarily projected onto a blank canvas, and what emerges is disturbing in ways that are disturbingly hard to define. It would be easier if she drew something green and blue, the celeste and verde she planned to use in her shop, but what associations do purple and yellow have for her? Giuliana wore purple in the Via Alighieri scene, and the trees in the swamp had been turned a muted purple by the effects of effluent (this is more visible in the Madman than in the BFI edition, both pictured below).

Yellow is also a prominent colour in the swamp and is generally associated with pollution throughout the film, but Valerio also uses it in his paintings to represent stars and rocket-flames, and the yellow light that invades the hotel room presumably comes from a street-lamp outside.

As we will see in Part 41, when we look at the video effects in The Oberwald Mystery, Antonioni may associate certain colours with certain moods while also varying these associations in surprising ways.

The purple spiral with a yellow streak may suggest the purple-clad Giuliana or a purple-ised tree, struck and wounded by a shard of poison. It may be a purple spaceship with a stardrive confusingly positioned so the jet-flame is contained within the main body of the vessel. Or, still catering to Valerio’s interest in outer space, it may be a purple nebula with a meteor tearing through it. Or we might look at the chalk-drawing drawing and, forgetting all the other imagery in Red Desert, see only a purple bruise around a piece of lacerated flesh, from which oozes a streak of lurid yellow pus.

Now, in Corrado’s hotel room, that chalk-drawing seems to have followed Giuliana and to be spreading across her environment like toxic mould. She clearly feels menaced by this shape because she swaddles herself up in the sheets, like Amelia hiding from the Babadook when it creeps across her ceiling.

The ceiling above a bed is a potent space for horror-film monsters to appear in, because it is the space we see while lying, vulnerably, on our backs, half immersed in or just waking up from a nightmare. Each aspect of the Babadook’s appearance can be correlated with an aspect of Amelia’s grief and depression, but Giuliana’s ceiling-stain is less clearly symbolic. I think it carries resonances from all the interpretations of the chalk-drawing I proposed above. We remember Giuliana in her purple shawl, dreaming of celeste e verde but surrounded by grey. We see her juxtaposed with those purple trees, staring into the yellow swamp-water. We think of Valerio and his futurist mindset, and how alienated Giuliana felt among his toys, vessels, models, and artworks. We see the internal projected externally: the confused, fluctuating colours of the unconscious warping our surroundings, and those surroundings turned into human flesh, with visible internal bleeding and festering open sores. Antonioni said of these intermingling colours, ‘I would have liked to film them while they were in motion, but I had to limit myself to fixed images.’3 Seymour Chatman argues that the finished film achieves the originally desired effect: ‘one does not so much see as feel the color move.’4 This is not only because of the strange angle and motion of the camera, but also because this abstract image carries so many unstable meanings, prompting a mix of emotions in the viewer that makes us ‘feel the colours move.’

Above, I noted that in the shot of Corrado looking down at Giuliana, his eyes visibly moved from the upper to the lower part of the bed. He occupied the upper part of the frame, divided from the lower part by the red metal bar extending diagonally from left to right. We then cut to the close-up of Giuliana as her eyes move from the wall to the ceiling, and in the following shot of the colourful stain, the upwards tilt causes the red metal bar to divide the frame.

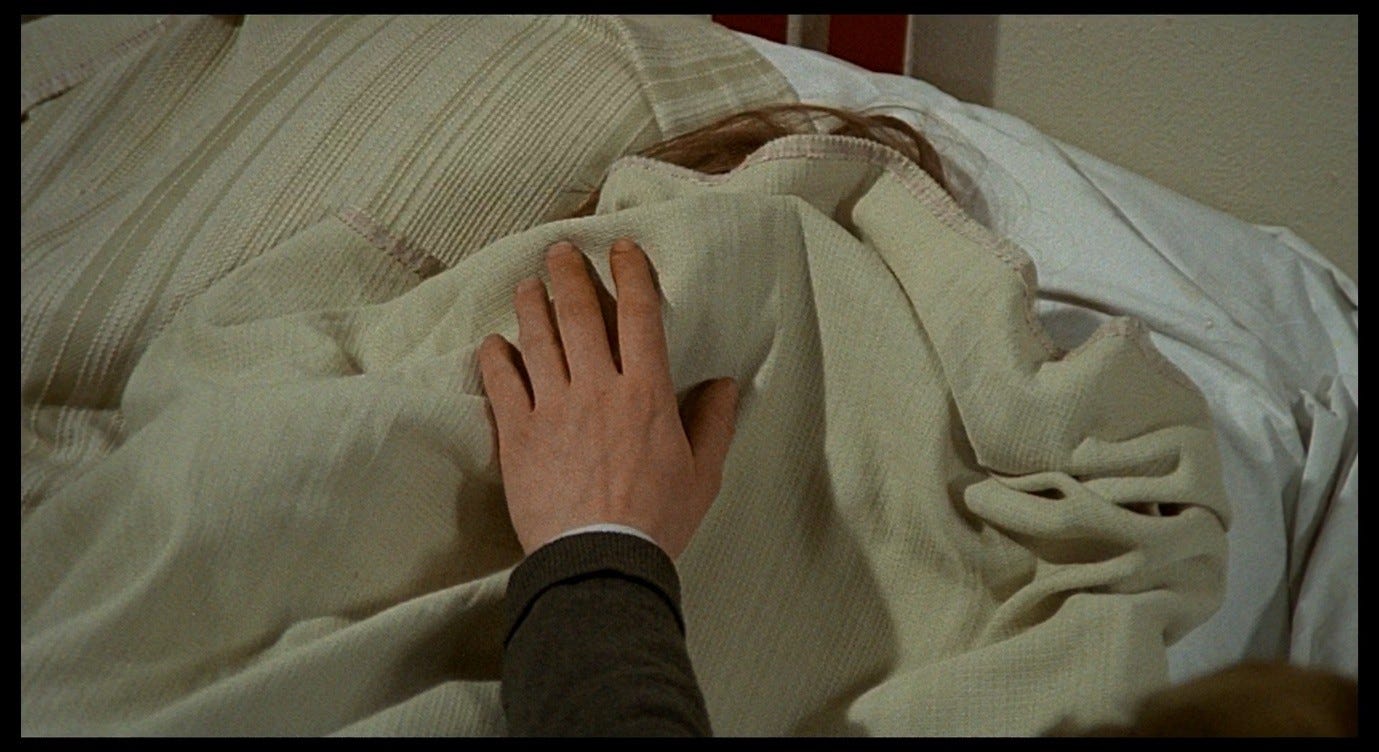

This series of images continues to underline the cross-purposed eyelines of the two characters. Just as, a moment earlier, Giuliana looked at the wall and Corrado looked at her legs, now her gaze moves from wall to ceiling and his moves from head to legs. There is also an association between the shot of Corrado, preying on Giuliana from above the red bar, and the menacing entity on the ceiling, similarly framed against the red bar. Both these shots are taken from that same ‘impossible’ perspective behind the bed, but in the one that shows Corrado, the red bar and Giuliana’s hair are out of focus, whereas in the one showing Giuliana’s perspective they are (more or less) in focus. The bar represents a boundary marking one space off from another, with Giuliana occupying the lower space and Corrado/ceiling-stain occupying the upper space. This barrier seems highly permeable, especially in the shot of Corrado where it is out of focus. The stain emanates from above and is extending into Giuliana’s space; after Giuliana covers herself up, we see Corrado move from the above-bar to the below-bar space, transgressing the boundary as he sits beside Giuliana and reaches out to touch her.

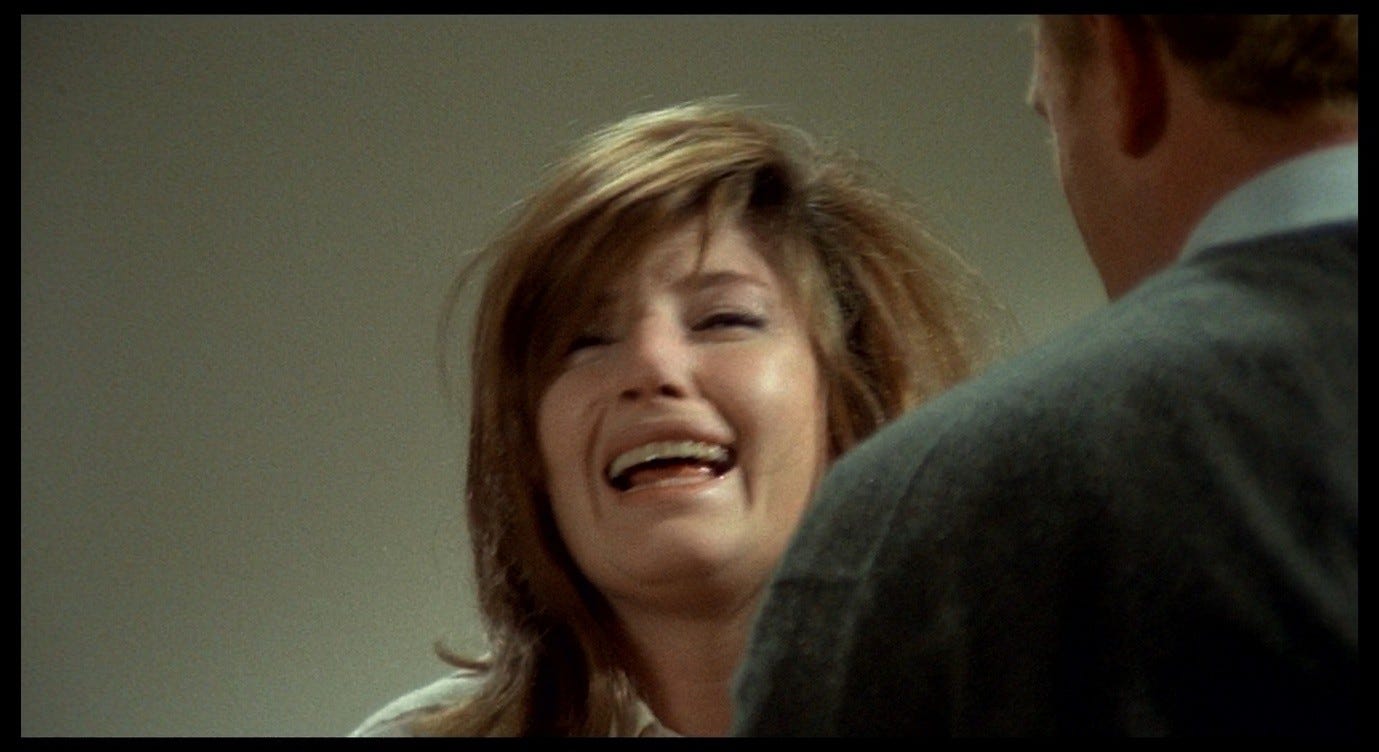

In response to his touch, Giuliana pulls down the sheet and looks up at him in alarm. Her pained expression conveys a desire to explain something to Corrado, in a tone of ‘Don’t you understand?’

She tells him, as if to warn him, that she sometimes has the urge to attack someone. He laughs this off, collapsing the distinction between them by affirming that he has violent urges too; he hopes this is not a ‘worrying symptom.’

The screenplay comments, ‘But for Giuliana this is not the moment for joking.’5 This scene is about Giuliana’s fear and her sense of being under threat from her environment, and in this context when she talks about wanting to attack someone, she seems to be referring to a defensive impulse. When Corrado approaches her like this, she wants to fend him off. When he smilingly admits to having similar violent impulses, this has different connotations. We might recall the satisfaction he took in ripping up the boards of Max’s shack, or his predatory approach to recruiting workers, which disturbed Giuliana. Corrado’s impulses are about to manifest themselves through another kind of violence, as we will see in Part 40, so although his joke seems to refer to people who annoy him (and whom he therefore wants to attack), in the present moment it will be more applicable to his treatment of Giuliana.

Years later, Antonioni would explore the relation between these violent and sexual impulses through the protagonist of Identification of a Woman. Niccolò, like the Gabriele Ferzetti characters in the earlier films, grapples with professional frustrations that bleed into his personal life. When he tries to intimidate the thug who has been hired to spy on him, this gesture of masculine self-assertion backfires: under the gaze of the nearby seminary students, Niccolò’s behaviour simply appears dangerous and irresponsible.

He is angered by this attempt to warn him away from the upper-class Mavi, and on a deeper level by his own sense of middle-class inferiority. The men in her social milieu wield great power but remain largely unseen. Even the presence of the spy-in-sunglasses is revealed by a pair of traffic mirrors; these people are seen indirectly, in reflections, and obscurely.

Someone accosts Mavi on a staircase but remains out of frame. Although Niccolò can literally see this man from where he stands, the exclusion of information here indicates that Niccolò is not in a position to identify or truly ‘see’ this stranger.

Later, when Mavi describes the encounter from her point of view, we do see the other man, and he turns out to be responsible for the threats against Niccolò.

Mavi herself remains, in a sense, unseen and un-knowable. Insofar as Niccolò is pursuing a sexual conquest, he achieves only mitigated success. Mavi’s health problems place strict limits on what they can do in bed: in the film’s most graphic sex scene, the focus is on her pleasure as she looks into a mirror, and Niccolò appears despondent – sulking, almost – after her orgasm.

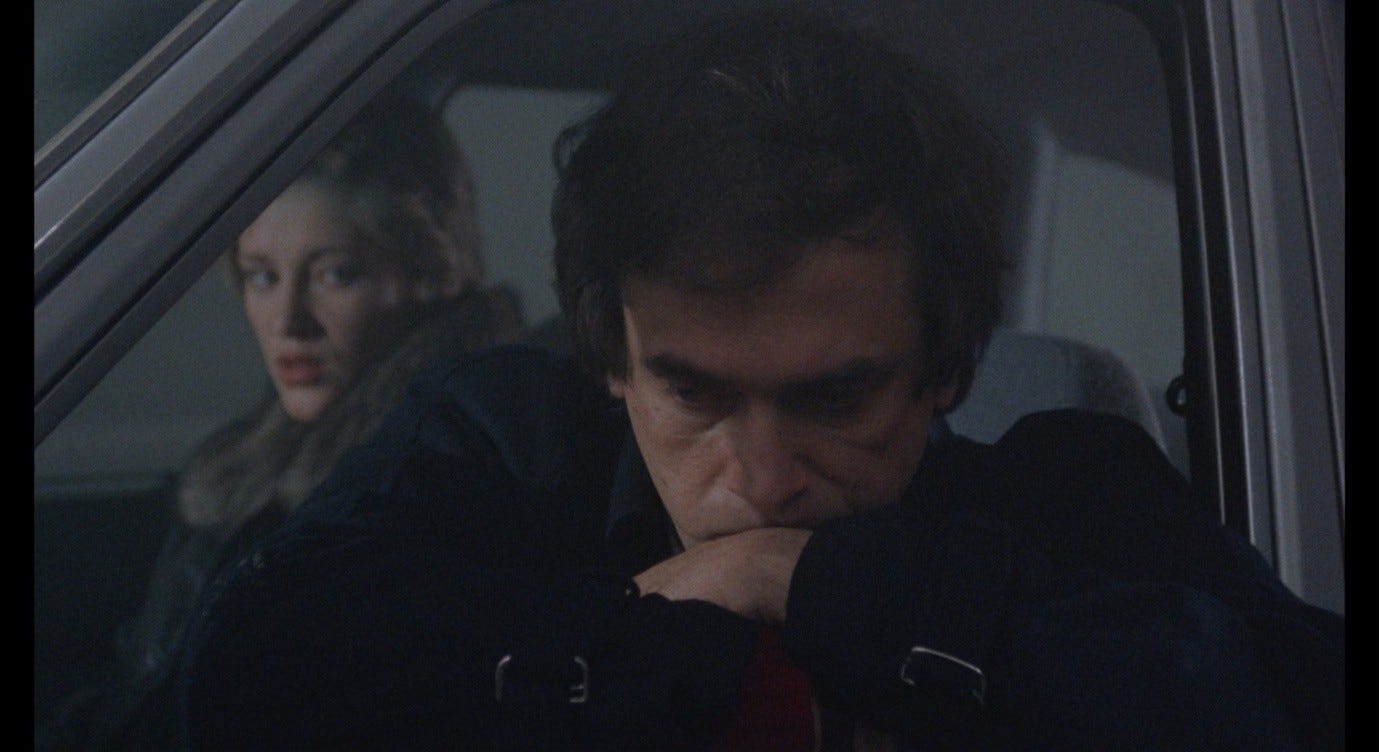

His sense of emasculation reaches a high-point during the ‘driving in fog’ sequence. He and Mavi disagree as to whether they are still being spied on: he says they are not, she insists they are. Niccolò brusquely declares that he will outrun the spies. He drives at terrifying speed through a fog so thick it makes even their immediate surroundings invisible, while Mavi becomes increasingly (and understandably) frenzied in the passenger seat.

It feels as though Niccolò is half-trying to kill both himself and Mavi. His extreme, abusive anger is a confused reaction to several things. The power and status of Mavi and her class are reflected in their elusiveness, in the secrecy with which they operate. This in turn seems to be manifested in the fog that Niccolò drives through: the fog represents something he needs to ‘save’ Mavi from, but also something that seeks to protect her (not least from him). In one particularly disorienting shot, we see Mavi from outside the windscreen, which is so fogged up that she is effectively invisible, unidentifiable. As her panic builds, Niccolò wipes away the internal condensation, revealing Mavi to us, identifying her so to speak, but also associating this act of identification with the danger he is subjecting her to.

It is obvious that Niccolò’s fury stems from feelings of impotence, but more specifically it stems from his inability to see, hear, or know certain things. His project of ‘identifying’ this woman, or a woman, is about comprehension. He needs to understand Mavi to be in a relationship with her, and he needs to understand the female protagonist in his next film in order to make the film. ‘Identification’ is essential to (though unachievable in) both projects. We might look at the obscuring mists that surround Niccolò and think again of Antonioni’s comment about women, that they ‘provide a much more subtle and uneasy filtering of reality than men do.’6 A subtle filter is also uneasy; it can phase into an out-of-focus image or a thickly clouded one.

Lost in the fog, impotent and ignorant, Niccolò’s desire for and anger towards Mavi seem inseparable. Crashing the car and killing them both would be a sort of consummation, a final victory over the forces trying to keep them apart, and a pseudo-triumphant act of masculine dominance. Despite the making-up scene and the playful frolic in bed that follow this traumatic incident, it is not surprising that Mavi leaves the next morning, without saying goodbye, and cuts Niccolò off entirely. When he does track her down, he belatedly realises that he is behaving like a predatory stalker and at last backs off. In the end, he comprehends enough about this woman and about himself to know that he should keep his distance.

Niccolò’s next film will not be about a woman after all, but a solitary journey into the sun, that classic symbol of knowledge and clarity, as unlike fog as can be. Identification of a Woman nonetheless ends with an unanswered, perhaps unanswerable question: ‘And then?’ Niccolò’s nephew is innocently wondering what the film will be about, but also asking what we do with knowledge once we possess it. That final image of the sun suddenly takes on a frightening, overwhelming quality, like a vision of reality that we are not equipped to deal with.

In a way, this is what the women (especially Mavi) have become for Niccolò as well. He feels compulsively drawn to them, but frightened by the consequences of getting too close and learning too much. To understand Mavi would be like staring into the sun – un-filtered reality rather than the ‘subtle filter’ that women represent to Antonioni. Another iteration of the ‘subtle filter’ comment suggests something about the source of Niccolò’s fear:

Women perhaps have a more subtle, more sincere way of filtering reality. Women instinctively possess an acumen that men don’t. They’re less hypocritical. Men are forced by their jobs, and by the daily relationships that they have with other men, to control themselves, to tone down their reactions, to hide their feelings. Women, less so. Of course, I could be wrong. Nevertheless, as a man, every day I am forced, often with a certain amount of surprise, to note how much more clear-sighted women are than men, and often how much braver they are too.7

Antonioni’s voice here is somewhat like Niccolò’s, not only because it is (perhaps consciously) patronising and misogynistic, but also because it expresses a mixture of admiration, envy, and terror in the face of women’s allegedly superior capacity for emotional expression. Peter Brunette critiques the above-quoted passage on the basis that

Besides its essentializing of certain so-called feminine characteristics (and its covert, but familiar strategy of associating women with the body or the animal through the use of words such as ‘instinctive’), Antonioni’s statement also implies that this filtered reality is ultimately the same for everyone, irrespective of gender: its essence, he might say, is just better shown by filtering it through women.8

I think this is indeed part of Antonioni’s meaning. As I said in Part 22, he seems to think that women experience reality in a more direct, sincere way, while men need filters (the subtler the better) like women or camera lenses in order to access this reality. The filter has to be clear-sighted and brave, capable of surprising the man who lives in a constant state of self-control, which (Antonioni implies) is really just hypocrisy. Brunette is neglecting this last point when he makes Antonioni sound so confident in using female filters to show the ‘essence of reality,’ or so confident in his knowledge that this reality is the same for all of us. In Identification of a Woman, Mavi knows things that Niccolò cannot, however much he strains to perceive them through her. This is why she is scared of the fog, highly sensitive in bed, and ultimately inaccessible to him; there is no possibility of a final conversation between them, let alone of an ongoing sexual relationship. Mavi ends up in a relationship (with another woman) into which neither Niccolò nor Antonioni’s film can give any insight. This may still be an essentialising view of men and women, as Brunette argues, but it is also shot through with uncertainty and punctuated by that characteristic refrain, ‘Of course I could be wrong.’

The example of Identification of a Woman tells us something important about the relationship between Corrado and Giuliana at the climax of Red Desert. Here too there is an emphasis on seeing and comprehension, as well as a divide between what each character can see and comprehend. Giuliana, like Mavi, occupies a plane of reality that is inaccessible to Corrado, and his violent erotic impulses seem in part to stem from his frustration at being shut out from something. His attempts to change the tone of the conversation are meant to bring Giuliana onto his wavelength, which is defined by self-control and hypocrisy. Whenever she tries to explain her feelings to him, he responds by flattening them out. He is not as overtly angry as Niccolò, but by the same token he seems more repressed and less self-aware. When he spaced out in the warehouse during the briefing scene, Corrado did not seem to know what he was feeling or why. It was no doubt something to do with Giuliana, but even now that he is face to face with her, he seems just as spaced out, staring at her and wanting her without knowing why. He is as distracted from her as he was from the workers he was busily exploiting.

Like Niccolò, Corrado is on a perpetual journey of discovery, but he is an industrialist rather than a film-maker. When we first met him, he explained that he began his career with mineral engineering (‘down’) and then moved into petrochemicals (‘up’) following the death of his father. Though he reversed his direction, he is still evading the ‘here and now,’ dedicating himself to the constant progress that industry demands. His dissatisfaction with this work is evident throughout the film, and resembles Niccolò’s hangdog cynicism about film-making. In a more conventional romance, Giuliana might represent a kind of escape, a breath of fresh air that makes Corrado re-assess his values. Instead, she represents something less attractive: a kind of end-point to his journey of discovery, but one that he cannot comprehend and does not want to arrive at.

‘There is something terrible [qualcosa di terribile] in reality,’ Giuliana will say to Corrado in the next scene, ‘but I don’t know what it is. No one will tell me.’ Ironically, she is the only person in the film who does know what this terrible thing is, because she has seen it in Corrado’s hotel room. In that from-behind-the-bed shot, when she sees the colourful entity on the ceiling, the layered composition recalls those oddly disturbing images of the lapping surf in Giuliana’s story. Her head and her hair merge with the fabrics and surfaces around them, all these things melding into each other and transmuting, just as the sand became the sea, the distant land, and the sky.

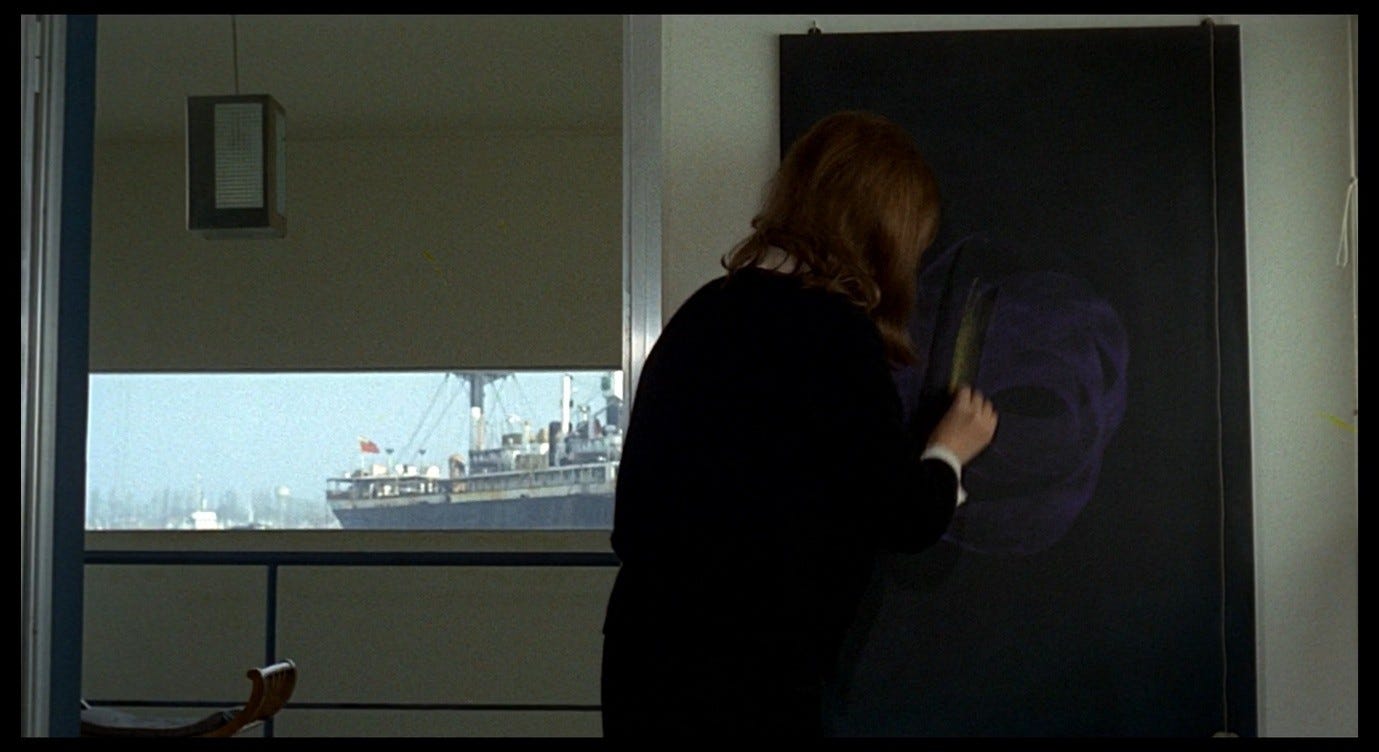

Crawling out from under the sheets, Giuliana rises to a kneeling position on the bed and shuffles backwards. She stops when she hears the clink of the red metal frame against the wall, signalling the physical boundary that was transgressed by the from-behind-the-bed shots, and that has now been restored and is making its presence felt. She turns to the wall and touches it with her fists, ‘as if to reassure herself that it is solid, that it will support her,’ as the screenplay says.9

In Satyajit Ray’s Devi, Doya makes a similar gesture when she is first mistaken for the goddess Kali. She turns from her worshippers, and from the camera, and drags her nails down a wall, leaving scratch-marks; after moving her nails vertically, she then drags them towards her, as though wanting to pull the wall closer for protection.

Her gesture is a protest against the disintegration of her reality, which has just begun. Later, when the disintegration is almost total, she will appear in front of a window through which the sun is shining so brightly that the light seems to dissolve both her and the wall and windows behind her.

It is a moment of sun-like revelation-through-madness, but as in Family Life there is no doubt that Doya’s ‘madness’ has been induced by the madness of her environment, and could have been avoided if reason had prevailed. Her divinity is simply a delusion; the blinding effect of the sunlight symbolises that delusion. Devika Girish reads Devi as ‘[dramatising] the ways in which the symbolic deification of women comes at the cost of their material agency;’ Doya is ‘frozen into an ideal before she can become her own person.’10 I do not think that Antonioni portrays women as goddesses or idealises them into symbols without agency, but there are some interesting overlaps here with his projection onto them of a more ‘sincere’ or ‘direct’ way of communing with reality.

Giuliana’s sense that her surroundings are falling apart is (arguably) not rooted in delusion, but in a lucidity that is experienced like that intolerable knowledge of the sun that Niccolò could only speculate about. She is overcome with terror and begs Corrado to help her: ‘Help me! Help me, please! I’m afraid I won’t make it! I’m afraid!’

Corrado grabs her by the shoulders and says, ‘Don’t do that, calm down. Why are you afraid? Of what [Di che cosa]?’ Her later comment about the qualcosa di terribile in reality is a kind of belated answer to Corrado’s di che cosa?, but for now she responds: ‘Of the streets, of the factories, of colours, of people, of everything [di tutto]!’

We see her in an intense close-up when she says this. At first, she looks into the middle distance and speaks almost blankly, in a kind of trance, but the terror in her voice builds as she continues to list things, as if those things were all crowding in on her at this moment. By the end of the list, she is hoarse with panic and she clutches Corrado desperately.

Giuliana’s list of frightening things echoes her list of love-objects in Mario’s apartment. There, she explained that the doctors advised her to love her husband, son, job, or dog, but not husband-son-job-dog-trees-factories, and as she pronounced the extended and hyphenated version of this list she became overwhelmed with fear and backed away into a corner.

The way she joined these words together, rather than listing them, indicated her desire for ‘everything [tutto],’ which was seen as transgressive by the doctors and which terrified Giuliana. At the end of her tale of the pink beach, she said that the mysterious song came from tutti; in Part 35, I argued that this was both a wish-fulfilment fantasy and an unsettling bad dream.

In the hotel room sequence we see that Giuliana is disturbed by her need for others: husband-son-job-dog-trees-factories becomes the protective wall made of loved-ones, which in turn becomes the ‘streets, factories, colours, people, tutto’ of which she is so frightened. Clearly, Giuliana’s fear is linked to her desire. Something about these wants and needs, this urge to connect with everything at once, which caused her bedtime story to dissolve back into reality, also makes her feel like she cannot survive. As she arrived in the hotel room, she said that she felt pain in her hair, her eyes, her throat, and her mouth – another list – and she looked down at her trembling limbs. Every part of her body suffers from sensory overload, to the point that this overload threatens to disintegrate her entirely. What is also clear by now is that the horror of her own desires is linked to the horror of Corrado’s. When she clutches him at the end of her final outburst, the gesture seems akin to the way she hid in the corner of the room, on the floor by the armchair, or against the wall behind the bed. It is not an amorous embrace – she has come here looking for refuge – but Corrado treats it as one.

Next: Part 40, What happens to Giuliana?

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 492

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 32-33

Mancini, Michele, Alessandro Cappabianca, Ciriaco Tiso, Jobst Grapow, ‘I am tired of today’s cinema’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 168-184; p. 180

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 132

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 492

Tornabuoni, Lietta, ‘Myself and cinema, myself and women’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 185-192; p. 191

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘A documentary on women’, in Unfinished Business, trans. Andrew Taylor (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 111-115; pp. 113-114

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 8-9

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 492

Girish, Devika, ‘Devi: Seeing and Believing’, Criterion.com (26 October 2021)