Everything That Happens in Red Desert (32)

Loneliness and childhood

Towards the end of The Sleepwalkers, Hermann Broch explores the themes of loneliness and alienation with reference to childhood, in ways that resonate with the childhood-centred aspects of Red Desert, and especially with the sequence (coming up in Parts 33-35) in which Valerio falls ill and Giuliana tells him the story of the pink beach. In Broch’s novel, children have an uncanny, disturbing quality, in part because they openly express or embody things – particularly loneliness – that the adult characters have learnt to disguise. In Red Desert, Valerio confronts Giuliana with her own loneliness in a way that provokes her climactic breakdown, and this same breakdown is also precipitated by Giuliana’s own expression of her loneliness through the avatar of the beach-dwelling girl in the story. The intersection of childhood and adult perspectives (on loneliness) is an important thread in the Broch-Antonioni connection, and one that will provide a useful way into the next sequence in Red Desert.

As well as the parallels between Hanna Wendling’s ‘nervousness’ and Giuliana’s ‘neurosis’ (discussed in Part 30), there is also an overlap in their increasing sense of alienation from their own homes and their own families. I cited some examples of this in Parts 10 and 11, with reference to the scene of Giuliana’s night terrors. Hanna Wendling’s home ceases to feel like her home, her child seems connected to her husband but not to her, and (linked to these forms of estrangement) her own bathroom mirror can no longer be relied upon to reflect a face that is ‘still hers.’1 She can barely look at her husband and son because they seem ‘absurdly alike... It was as though she had no share at all in the child.’2 Hanna’s experience of uncanny terror has something in common with Joachim’s and Elisabeth’s in their engagement scene (see Part 31). The narrator observes that Hanna is moving towards that ‘ultimate state of entropy [...] an absolute zero towards which all movement perpetually and of necessity strives,’ and that this state entails a blurring of boundaries between things and people:

[F]or the entropy of man implies his absolute isolation, and that which hitherto he has called harmony or equilibrium was perhaps only an image, an image of the social structure, which he made for himself, and could not help making, so long as he remained a part of it. But the more lonely he becomes, the more disintegrated and isolated will things seem to him, the more indifferent he must become to the connections between things, and finally he will scarcely be able any longer to see those connections. So Hanna Wendling walked through the house, walked through her garden, walked over paths which were laid with crazy-paving in the English style, and she no longer saw the pattern, no longer saw the windings of the white paths.3

There is a kind of paradox here, in that the dissolution of connections results partly from an awareness of those connections. Hanna becomes aware of the structures in her life, structures which she has helped to make and could not help making, as she is a part of them; but in recognising these as constructed things, she also sees them begin to dissolve and feels alienated from them. This feeling is succinctly encapsulated in the moment when she sees her husband and son side by side. The son is a perpetuation of his father, another Heinrich, and somehow this appearance of a pattern (like the patterns in her home or her garden) induces an awareness of how arbitrary and contingent those patterns are. Because everything is constructed, everything can be deconstructed, indeed everything might as well be deconstructed. This revelation is, so to speak, the ‘adult’ experience of loneliness, arrived at following years of careful home-construction and parenting.

Broch also portrays the onset of loneliness from the perspective of a child, through the character Marguerite, an eight-year-old war orphan in the 1918 section of the novel. During a prison riot, she stands outside and dances in time to the prisoners’ chant of ‘We’re hungry, we’re hungry.’ Joachim (now an elderly Major) is shaken by this juxtaposition:

The Major gazed at the building with the dreadful impenetrable windows, he gazed at the dancing child whose laughter seemed to him strangely mechanical, strangely evil, and horror overwhelmed him.4

Like Valerio’s mechanical side-stepping dance during the (equally mechanical) strike at the start of Red Desert, there is something disturbing about the ‘play’ of this child in this context.

Stephen Dowden reads the prison riot as ‘Broch’s scaled-down representation for World War One as the outburst of an entire culture’s bacchanalian drive to self-negation,’5 and he sees Marguerite as embodying something of modern humanity’s ‘kinship with the machine’s insensate functioning.’6 Watching her dance outside the prison, Joachim is on one level responding to the callousness of a child dancing to the sound of hungry, rioting prisoners. It is like the callousness of humanity in the face of war, a depressing reminder of how inert our feelings can be in contrast to the seeming progressiveness of the world we live in. It is also another manifestation of the paradox I noted above: like the son replicating the father, Marguerite imitates the prisoners’ chanting, but the connection thus formed is ‘strangely mechanical, strangely evil.’ Because these things are connected, connections disintegrate.

However, Joachim’s reaction to Marguerite’s behaviour is limited and reductive, as the narrator reveals shortly afterwards. We last see Marguerite wandering out of the town, into the countryside, towards an unknown fate, and this final journey of hers – the end of her story in the novel, and perhaps the end of her life – prompts the narrator to reflect on the true significance of children’s seemingly idle or uncanny laughter. He begins with children’s relationship to nature, but connects this to their way of processing fear and loneliness:

Children have a more restricted and yet a more intense feeling for nature than grown-ups. They will never linger at a beautiful prospect to absorb the whole of a landscape, but a tree standing on a distant hill can attract them so strongly that they feel as if they could take it in their mouths and must run to touch it. And when a great valley spreads before their feet they do not want to gaze at it, but to fling themselves into it as if they could fling their own fears in too; that is why children are in such constant and often purposeless movement, rolling in the grass, climbing trees, trying to eat leaves, and finally concealing themselves in the top of a tree or deep in the dark security of a bush. Much, therefore, of what is generally ascribed to the sheer inexhaustibility of a youth’s unfolding powers and to its purposeless yet purposeful exuberance is really nothing else than the naked fear of the creature that has begun to die in realizing its own loneliness; a child rushes to and fro because in so many senses it is wandering about at the beginning of its course; the laughter of a child, so often censured by adults as idle, is the laughter of one who sees himself surprised and mastered by loneliness: so [...] an eight-year-old may decide to go out into the world in an extraordinary, one might almost say, an heroic and final attempt to concentrate her own loneliness and conquer within that the greater loneliness, to challenge infinity by unity and unity by infinity.7

Childhood play is, Broch argues, rooted in fear. The child looks at a landscape and wants to grab and consume a tree in the far distance, or to hide in the ‘dark security’ of foliage; or they want to fling themselves into the landscape, ‘as if they could fling their own fears in too.’ These impulses are contrasted with the adult gaze that appreciates the view and ‘absorbs’ it, as though mastering it. The child’s impulses are also attempts at control, but more confused and spasmodic, doomed to failure, purposeful and purposeless at the same time. The child sees the tree at a great distance and they feel like they can collapse that difference. They think that by flinging themselves into the landscape they can expunge an unwanted part of themselves. But they are ‘wandering about at the beginning of their course,’ and in the process discovering that these feats are impossible. As such, they are ‘surprised and mastered by loneliness.’

From an adult point of view, one might be absorbing and appreciating a landscape and then suddenly realise how arbitrary and de-construct-able one’s sense of appreciation is, how artificial are the aesthetic preconceptions one imposes on this view. The child has none of these preconceptions, but has a more visceral realisation of their connectedness and disconnectedness: the world is so vast and plural and they are so small and singular; they feel so intensely engaged with the objects of their desire and yet helplessly alienated from them; their fears seem to be located in external things, or capable of being externalised (as if one could fling them away), and yet they remain internal, inextricable from the individual’s experience of life. Antonioni explored something like this state of mind in his story, ‘Two Telegrams’, of whose protagonist the narrator says:

The indifference of Nature was the dramatic discovery of her adolescence. It wasn’t enough for her to look at those vast green and yellow landscapes, she wanted somehow to be part of them, to upset their undulations, their cadences.8

As an adult, she longs for her ‘relations to others to be less bound to conventions,’9 and in her office she experiences an ‘intersection of loneliness [compenetrarsi di solitudini],’10 literally an interpenetration of lonelinesses – that of her inner state and that embodied in her surroundings, the ‘relation between inside and outside [rapporto interno-esterno]’11 – a collapse of the conventions that govern what she is or is not connected to and part of. In the end she attacks her colleagues with a pair of scissors. ‘No matter who,’ she thinks; ‘One of them.’12

The child who confronts Nature and is ‘surprised and mastered by loneliness’ expresses this feeling through exuberant, idle play, but their play represents in miniature the violence into which it will bloom in adulthood. Marguerite’s dance outside the prison is the mirror-image of the horror Joachim feels when he watches her dancing, and this 1918 horror is related to the horror he felt in the company of Bertrand and Elisabeth in the first part of the novel. Like the child wanting to grasp the faraway tree, Marguerite senses the distance between herself and the prisoners – and her distance from their hunger and distress – and illustrates this through her seemingly (deliberately) callous, mechanical dance. Her venturing out into the wild is a way of grappling with the same feelings on a cosmic scale. This ‘almost heroic’ journey is said to ‘concentrate’ Marguerite’s loneliness, as if the journey were a kind of symbolic gesture representing the isolation of the orphaned and un-moored. But the journey is also meant to ‘conquer within that the greater loneliness, to challenge infinity by unity and unity by infinity.’ Embodying loneliness conquers loneliness; the single entity and the boundless sea are pitted against each other; connections indicate disconnection.

These dizzying tensions and contradictions are like the ones Giuliana faces in Red Desert, as she longs for but also fears the blurred-together world, as she rejects the world of discrete, single things but also tries to find a single thread to focus on. Her suicide attempts – driving headlong into traffic or into the sea – are like Marguerite’s ‘flinging’ of herself into the unknown.

And Valerio’s ‘one plus one’ trick, which immediately follows that second suicide attempt, challenges unity with infinity and infinity with unity: the drops could be multiplied forever and still only form ‘one’ enormous body of water; the isolated individual can take on infinite proportions, but by the same token they will remain an isolated individual.

It is a childish joke but Valerio executes it without a trace of a smile, sensing on a primal level how deeply this joke will cut into his mother’s existential crisis. He hears her saying, ‘I’m hungry!’ and he echoes this back at her in a tone of mockery.

Before leaving Marguerite to her fate, the narrator of The Sleepwalkers offers some final insights into the child’s state of mind, and some final reflections on the significance of her quest:

She is suddenly aware that there is no fixed goal for her, that her casting about and seeking for a goal has been in vain, that only the infinite distance itself can be a goal. The child does not formulate this thought, but she answers with her actions the question she has not posed, she flings herself into the strangeness, she flees along the road, she flees along the road that stretches without end, she loses her wits and cannot even weep in her breathless race that is like a suspension of movement between the moveless masses of cloud. And when the evening really steals upon her through the clouds, when the moon becomes a bright patch in the cloudy roof, when the clouds are then washed away by some noiseless force and all the stars are vaulted above her, when the stillness of dusk is superseded by the immobility of night, she finds herself in an unknown village, stumbling through silent alleys in which here and there a cart is standing without its horses. It is almost a matter of no account how far Marguerite will penetrate, whether she will ever be brought back or whether she will fall a prey to some wandering tramp – the sleepwalking of the infinite has seized upon her and never more will let her go.13

The sense of lacking a ‘fixed goal’ is a response to the sickness with which Broch diagnoses the modern world, that ‘singleness of purpose’ which dictates that all things, people, and objects must serve specific functions. Marguerite’s goal-less-ness is both an allergic reaction to that mindset and a kind of antidote to it. All goals and purposes fall away as the ‘infinite distance’ opens up around her, first in the form of the ‘road that stretches without end,’ then in the sky that clears to reveal the stars, then in the shift from ‘stillness’ to ‘immobility’ as the night wears on. Again, Marguerite’s actions have a symbolic, expressive quality that she cannot articulate in words: ‘they answer the question she has not posed.’ Through these actions, she ‘loses her wits,’ cannot express emotions outwardly (‘she cannot even weep’), and ultimately becomes immune to all external influences. Whatever happens to her, whether she is saved or destroyed, ‘the sleepwalking of the infinite has seized upon her and never more will let her go.’ This is a permanent, incurable condition, for Marguerite as for Hanna, Joachim, or Elisabeth, whether they die young or grow old.

To describe this condition as ‘sleepwalking’ presents us with another variation on the central paradox Broch is exploring. A sleepwalker is a contradictory figure, asleep but active, and Marguerite’s sleepwalking combines awareness and obliviousness. She becomes oblivious to the things around her and to her own rational faculties, but aware of (to the point of being merged with) ‘the infinite,’ the endlessly expanding universe that has ‘stolen upon her’ or ‘seized upon her.’ Giuliana, in Red Desert, often appears to be sleep-walking in a similar fashion, un-meshed from the mechanical gears of her literal surroundings but thoroughly in touch with another plane of reality. She is nearly always tired and dazed, unsure of where to go or what to do, yet she is alert to phenomena that escape everyone else’s attention. Gazing at a landscape, she becomes intensely absorbed in specific aspects of it – disintegrating slag-heaps, burnt-out houses, ships moving through forests – and has to be woken up and dragged away.

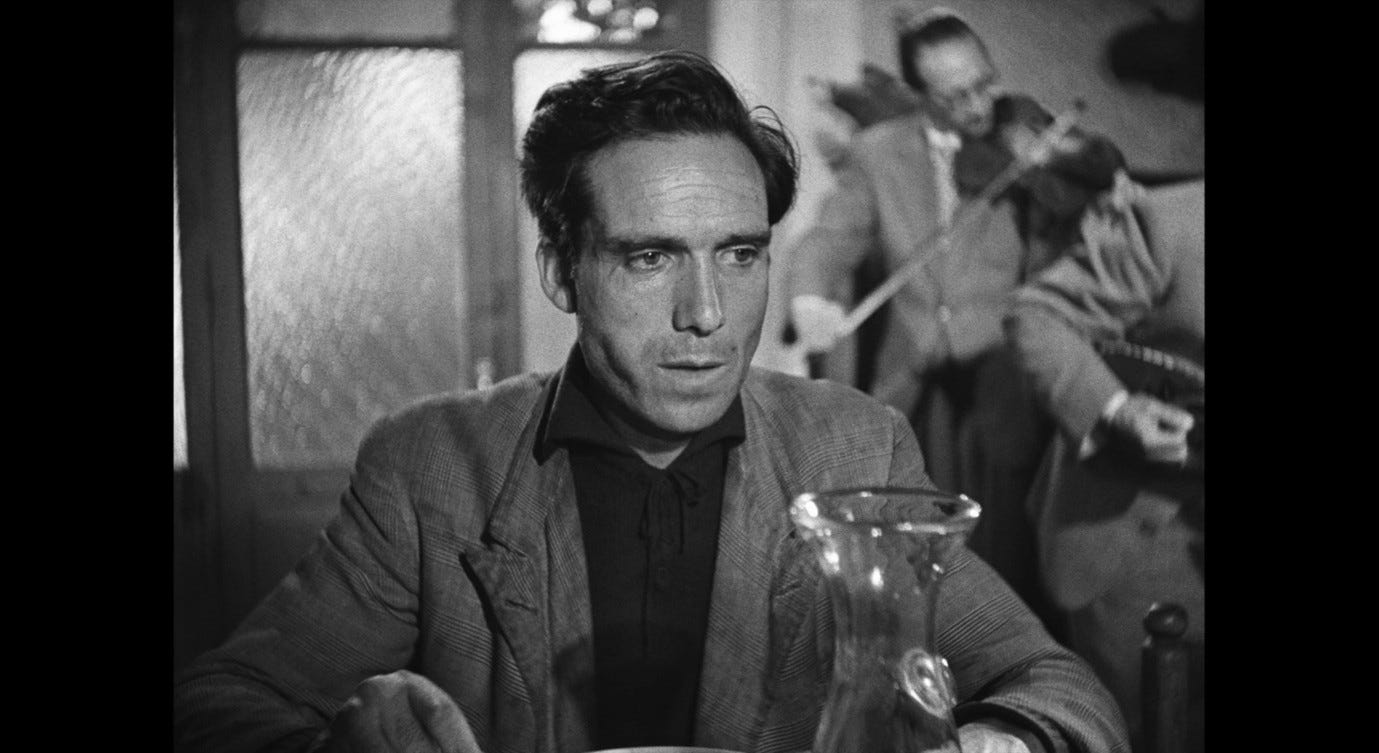

In this respect she has a lot in common with Aldo in Il grido, whose relationship with his daughter Rosina is a precursor to the parent/child dynamic in Red Desert. After his break-up with Irma, Aldo takes Rosina on a months-long odyssey from one temporary dwelling to another in the Po valley. He is by turns oblivious to Rosina’s presence and spasmodically solicitous over her. In one scene, she approaches a school gate behind which some children are playing football. When the ball flies over the gate, Rosina runs across the road to retrieve it, and is almost hit by a car. Aldo grabs her and slaps her for being so careless, and she runs away into a small valley alongside a nearby crop-field, like the child Broch described ‘flinging themselves into a valley as if they could fling their own fears in too.’

There, Rosina encounters a group of men from a local asylum: she walks among them, looking curiously up at them as they ignore her, absorbed as they are in their own realities. Then one of the men shows an interest in her and tentatively reaches out his hand. Rosina becomes terrified and begins to cry, prompting the man to withdraw. At this point, Aldo catches up to her and carries her away, comforting her and saying, ‘Don’t cry, don’t cry.’

The sequence is a re-working of the one in Bicycle Thieves when Antonio slaps Bruno (for criticising his approach to retrieving the bicycle) and Bruno bursts into tears and refuses to come near him.

Antonio leaves Bruno standing by a bridge while he goes off to look for the bicycle thief, but after a few moments he hears people screaming for help because a boy is drowning in the Tiber. He runs over to them and is relieved to see that the boy – who has been rescued – is not Bruno. When father and son are then reunited, Antonio repairs their bond by taking Bruno for a nice meal, even though they cannot afford the expense.

It is a brilliant and moving scene that shows how poverty affects interpersonal relationships: the loss of Antonio’s livelihood threatens his connection with Bruno (whose outraged reaction shows that his father does not normally slap him), and the thing that repairs that connection in turn threatens their livelihood (Bruno’s delight shows that he is not used to eating like this). ‘You need to earn a million a month to eat here,’ says Antonio ruefully as they half-enjoy their food.

The differences between these two scenes illustrate very clearly what Antonioni meant when he talked about the ‘problem of the bicycle,’ that is, the difference between the economic pressures explored by Italian film-makers in the immediate post-war years and the psychological pressures that came to the fore as the economy recovered (see Part 16). Il grido is not about a man who loses his livelihood. Aldo has a secure job at the sugar refinery in Goriano, but the disintegration of his common-law marriage with Irma prompts him to become an itinerant labourer. His struggles to find a job have more to do with his unusual status as a drifter-with-a-daughter (the child cannot live on a construction site, nor can they afford to live in a big city) than with any job shortage. When he slaps Rosina, the context is not a falling-out over how they can sustain their material needs. It is Rosina’s longing to return to her normal life, to go to school, play with other children, and escape from the dark cloud of depression that envelops her psychically devastated father. Her near-miss with the speeding car echoes several moments in Bicycle Thieves when Bruno is almost run over, or falls in the street, or is in danger of being molested, and Antonio is too busy worrying about his bicycle to notice.

Aldo, by contrast, notices that Rosina is in danger, but he is angered by his own sense of guilt. It is his fault that she is on the dangerous side of the school gate, and unlike in Bicycle Thieves there are no financial straits forcing them into this situation, just Aldo’s own sense of inertia.

Rosina’s encounter with the asylum inmates is a telling variation on Bruno’s supposed drowning in the Tiber and his encounter with the would-be child molester. Rosina is not in either kind of danger – the asylum inmates are not violent, nor does their interest in her come across as predatory – but she still recoils in distress and has to be rescued by her father. When Aldo reaches out to comfort her, the framing is very similar to the moment when the old man reached out to her, and when father and daughter walk away at the end of the scene, they are moving towards (and in the same direction as) the asylum inmates. Aldo is taking Rosina along the same path she took to get away from him.

The landscape is so shrouded in fog that the sky seems to dissolve into the land, and vice versa. It evokes Broch’s description of the girl who ‘flees along the road that stretches without end, in her breathless race that is like a suspension of movement between the moveless masses of cloud.’ The catch-22 from Bicycle Thieves takes on a different form here: it is something dark inside Aldo that ruptures his bond with Rosina, and when that bond is repaired it brings her back into proximity with that inner darkness. Aldo ultimately sends Rosina back to Goriano and to her mother, saying to her as she leaves, ‘Your father can’t explain why he doesn’t have the will [voglia] to work anymore.’ She seems stable in the foreground, looking out of the window of the bus, while he becomes blurry and indistinct as he runs alongside – this is the last time Rosina will see her father alive. When we next see her (at the end of the film) she seems to be living happily with Irma and a new father-figure.

However, the dynamic here is more nuanced than a binary opposition between the well-adjusted child and the maladjusted father. In an interview, Antonioni commented on the encounter with the asylum inmates in Il grido:

I liked the sequence with all the lunatics – and almost all of them were lunatics in real life. I always got along well with mentally ill people. One of my uncles was mentally ill, and when I was a child the family entrusted him to me and we got along very well. Mentally ill people see things that we cannot see. I do not believe in reason too much.14

As Rosina walks among these men enjoying their day out, it is apparent that they ‘see things that we cannot see,’ as they look in alarm towards the camera, or off into the distance, or at some imaginary interlocutor.

One of them cradles a doll as though it were alive, then wanders off as though offended when Rosina looks at him.

What terrifies her about the other man’s gesture is the sense that, far from being ignored or avoided by these people, she might be noticed by and connected with them – that if they can see her, she can see what they see, and see it in herself.

Later, Rosina bonds with Virginia’s elderly father, who – like the asylum inmates – gets put away in a home where he will pose less of a danger (or inconvenience) to those around him. Rosina and the old man mirror each other’s delight in playing with the goods that have fallen off a passing truck, and this is the last straw for Virginia: her father acts ‘like a child,’ so he has to go into a home. By the same token, Rosina was acting like the old man, finding a kinship with him that has something in common with her more unsettling kinship with the asylum inmates.

Happy as Rosina seems at the end of Il grido, there is a lingering sense that what she saw during those few months alone with her father will stay with her and have a lasting impact. Broch’s ‘child surprised by loneliness,’ laughing and playing when faced with mortality, yet at the same time shaken to the core by this confrontation, seized by ‘the sleepwalking of the infinite,’ is a useful analogue for Rosina. Broch imagines the tangible dangers Marguerite might fall prey to as she vanishes into the wilderness, including being murdered by a ‘wandering tramp,’ but the literal reality of what happens to her is ‘almost a matter of no account’ because, on a deeper level, the child has been seized by something far more consequential. Antonioni’s task, as he saw it, was

to examine the individual himself, to look inside the individual and see, after all he had been through (the war, the immediate postwar situation, all the events that were currently taking place and which were of sufficient gravity to leave their mark upon society and the individual) – out of all this, to see what remained inside the individual.15

Rosina’s encounter with the wandering asylum inmates is like Marguerite’s with the murderous tramp: what literally happens here is almost of no account compared to its existential significance. The man who is lost in his own version of reality, asleep and yet awake, oblivious to his surroundings and yet seeing something that others cannot, helplessly isolated and yet reaching out to make a connection – this man is a mirror-image of Rosina’s father, who is in turn a mirror-image of something terrible in reality.

When Rosina sees Aldo and Virginia making love by the roadside, she is appalled and runs away. Aldo watches her go, slumps his head, and mutters, ‘Irma…’

In a more sentimental film, the point of this scene would be that Rosina is upset over the break-up of her parents’ marriage, and that Aldo too remembers his lost love and longs to have her back. But Aldo’s repeated cries of ‘Irma’ mean something more than romantic yearning. The loss of Irma is like Broch’s disintegration of values, or the disappearance of Anna in L’avventura, or Aldo’s own ambiguous death at the end of Il grido. As I argued in Part 20, Irma’s cry when she sees Aldo fall expresses a complex kind of pain – both the pain of seeing someone die and the pain of seeing that their death is ‘of almost no account.’

When Aldo says ‘Irma,’ he is talking more about loss as such than about the specific person lost; he is reckoning with the implications of that loss as he replays it compulsively with every other person he encounters.

After Il grido, Antonioni’s films draw even less of a distinction between those who are seized by sleepwalking and those who are wide awake. The vanishing of Anna has an irreparable effect on Claudia’s and Sandro’s sense of what it means to still be ‘here,’ and the night and the eclipse envelop all the characters in La notte and L’eclisse. Red Desert reprises the dynamic of Il grido, but with an even more Broch-like ‘child surprised by loneliness’ witnessing the parent’s breakdown, and then a second child illustrating that breakdown through their encounter with nature. Valerio and the girl on the beach, in the next sequence of Red Desert, are both grappling with new forms of awareness, new understandings of how they relate to the world. They act in a way that might seem inexplicable, or even – in the case of Valerio – cruel and callous to an adult, but like Marguerite in The Sleepwalkers, they may simply be expressing their discovery of the connecting-but-isolating universe in which they suddenly find themselves.

Next: Part 33, Valerio’s paralysis.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 6955

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 8498

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 7217

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 10570

Dowden, Stephen D., Sympathy for the Abyss: A Study in the Novel of German Modernism: Kafka, Broch, Musil, and Thomas Mann (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1986), p. 54

Dowden, Stephen D., Sympathy for the Abyss: A Study in the Novel of German Modernism: Kafka, Broch, Musil, and Thomas Mann (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1986), p. 52

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 10890-10900

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Two Telegrams’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 15-22; p. 17

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Two Telegrams’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 15-22; p. 17

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Two Telegrams’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 15-22; p. 22. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Due telegrammi’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 19-28; p. 26.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Two Telegrams’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 15-22; p. 22. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Due telegrammi’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 19-28; p. 26.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Two Telegrams’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 15-22; p. 22

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers (1930-1932), trans. Willa and Edwin Muir (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), Kindle edition, loc. 10934-43

Tornabuoni, Lietta, ‘Myself and Cinema, Myself and Women’, trans. Dana Renga, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 185-192; p. 192

‘A Talk with Antonioni on His Work’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; pp. 22-23