Everything That Happens in Red Desert (20)

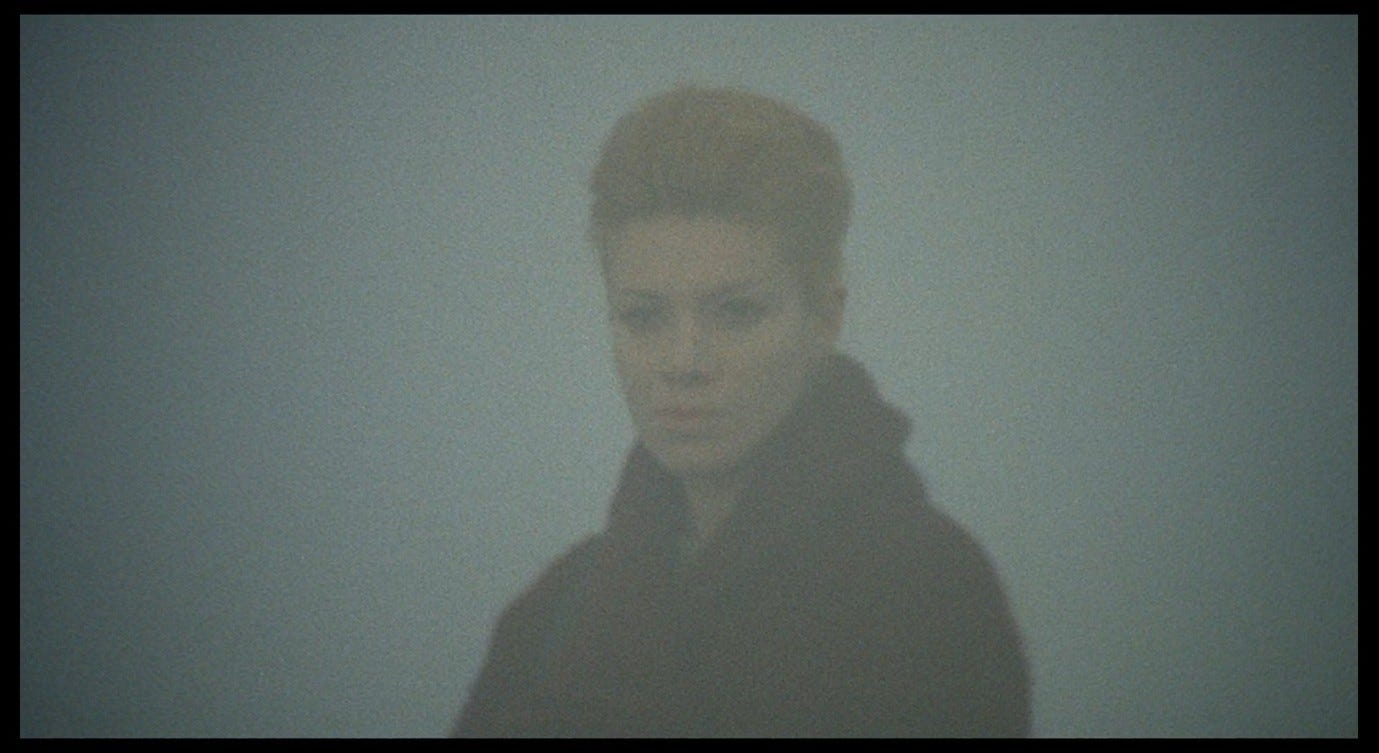

Something terrible in the fog

A blood-curdling cry of pain is heard outside Max’s shack. It seems to come from the fog that surrounds the port of Ravenna, and for a while nobody but Giuliana seems to have heard it. But the sense of nearby danger becomes overwhelming: the whole party flees the shack and runs down the pier towards their cars, only to be swallowed up by the fog that rolls in off the water. Something about this fog so terrifies Giuliana that she drives her car towards, and almost into, the sea, in what appears to be an attempt at suicide. This is the climax towards which the daytrip sequence has been building, and it will be helpful to explore the significance of this climax before we look more closely at the dialogues between Giuliana and Corrado (in Parts 21 and 22).

In ‘That Bowling Alley on the Tiber’, Antonioni tells the story of a man who, after a game of bowling, randomly murders two children. The setting is Rome’s Olympic Village, a modernist housing complex built for the 1960 Olympics but poorly maintained in the decades afterwards. The protagonist of ‘Bowling Alley’ sees the children playing in a field and experiences a mixture of emotions:

What strikes him in this place is a feeling that might be a feeling of peace if it weren’t, depressingly [pesantemente], a feeling of inertia, of death. The front of the low building is all peeling away, the fixtures have turned black, even the grass in the field and the trees seem resigned to neglect.1

The place resembles the periferia (on the outskirts of Milan) where Lidia wanders in La notte: a refuge from the bustle of the city, but infected with a heavy sense of lassitude and decay.

In ‘Bowling Alley’, the man watches the two children playing in a field, and his friendly manner causes them to approach him – they barely have time to register what is happening as they are shot dead. The man drives off as the children’s mother, unable to see the bodies in the long grass, calls out to them from a window of their home, in an echo of the opening scene from Fritz Lang’s M.

Such is the ‘action’ of this short story, but ‘Bowling Alley’ is less about the tale ostensibly being told, and more about the process whereby such an idea might (but in this case never will) turn into a feature film. Antonioni (in real life) sees a stranger leaving a bowling alley and imagines a story based around him. ‘Experience teaches me that when an intuition is beautiful [bella], it is also correct [giusta],’2 he says, which does not mean that the real-life stranger probably was a child murderer, but that the fantasy that came into Antonioni’s mind seemed like a viable idea for a film. The film, he says, would have to tackle the viewer’s questions about what had happened and why, but here, in this embryonic form, it can remain obscure:

Just as [Come] in Ferrara, where I was born, the winter fog descends so thickly that you cannot see a metre in front of you, just so [così] this idea came into my imagination. At a certain point one is lost [smarrita] in the fog.3

The word smarrita perhaps recalls the opening lines of Dante’s Commedia: Dante finds himself in a ‘dark wood [selva oscura]’ where ‘the right way was lost [la diritta via era smarrita].’4 Antonioni’s sentence is structured like a classical extended simile, with the Come…così structure sometimes used by Dante, as in:

Come d’autonno si levan le foglie […]

Così sen vanno su per l’onda bruna.5

But this classical tone is ironic, because Antonioni is explaining why this modest work of art will remain oscura and will never find the diritta via to become a coherent film treatment. He tries to ‘individuate, in this fog, a few certain points [individuare, in questa nebbia, alcuni punti certi],’ suggesting for instance that the man kills these children to spare them from what he presumes is a miserable existence; this is an ‘act of love’ and an act of ‘faith in something different,’ born out of a belief that these children deserve better.6 But in the final paragraph, Antonioni restores the thick Ferrarese mists, which are the key ingredient of the text:

The rest is fog. I’m used [abituato] to it. To the fogs that envelop our fantasies and the fog of Ferrara. Here, in winter, when the fog moved in, I liked walking the streets. It was the only moment when I could think I was somewhere else [essere altrove].7

The desire to essere altrove is akin to the desire (discussed in Part 17) to essere un’altra, to be another person, whether by looking in the mirror, acting a part, being in love, or otherwise displacing your problems onto a mirror-self. For Antonioni, the artistic process is a way of ‘being otherwise,’ of inhabiting other possible selves and settings. The fog enables this precisely by obscuring everything. It renders your surroundings invisible so that, rather than remembering what is ‘really there’ beneath the fog, you can imagine something else. When Antonioni sees a man acting weirdly in a car park outside a bowling alley, he does not introduce himself and take an interest this man’s actual life. Instead, he allows the fog to descend and his intuition to take over.

The story is built around seeming contradictions: between the man’s geniality and his murderous actions; between his concern for the children’s welfare and his destruction of them; and between Antonioni’s claim that this story is bella and the story’s focus on child murder. When the police investigate, they are unable to recognise the man as a murderer because ‘his crime fits [si inserisce] so well into the social context in which it happens, because it’s so normal, that is, among so many atrocious crimes.’8 That social context is like the fog as well: the crime gets lost (si smarrita) and becomes something else, something normal, as invisible as the corpses lying in the long grass of the neglected field. Antonioni is abituato to the fog, he says: to the literal fog of Ferrara, to the obscurity of the ideas that come to him, but also (perhaps) to the everyday atrocities of modern life, the violence that gives the red desert its colour.

Red Desert is about a woman who cannot habituate to modern life, and her panicked reaction to the fog in the present sequence is one among many symptoms of this failure to adapt. But the analogue of ‘That Bowling Alley on the Tiber’ suggests another way of looking at Giuliana. Just as Antonioni ‘individuates’ certain specific points within the mist, but then gives up and abandons everything else to the fog, so Giuliana struggles with individuation amidst the prevailing amorphousness. If she seems less sanguine about this than her cold-blooded creator, it is because she represents that part of him that can see those corpses in the grass, identify the man as a murderer, and feel the horror of both this crime and the social context in which it takes place. To me, one of the most striking details in ‘Bowling Alley’ is that the imagined murder takes place on ‘a strange day at the end of winter, no sun but bright, full of details.’9 In other words, if this were a scene in a film, there would not be any fog: Antonioni would show us every detail in that cold winter light. This is another contradiction, between the lucidity of the imagined images and the obscure mists that deliver those images to Antonioni’s mind. Giuliana sees out-of-focus, but also with a kind of clarity; she hears sounds that are not really there, but she also hears the scream that remains inaudible to others (or that they choose not to notice).

Max’s shack is supposed to be in a cleaner, safer space than Ugo’s, but when we look out of the windows, and especially when we see the shack from outside (in context, so to speak), there is something haunting about the dense fog that surrounds it on all sides.

The anguished cry from outside partakes of the same haunting quality as the fog. It is both clear and obscure: it is incorporated into the soundtrack in such a way that it does not quite seem to come from inside or outside; it seems to be from a different soundtrack, like a background notification from an unknown app. We see Giuliana react to the cry, which is how we know we really heard it ourselves. She rises up and looks alarmed, and Linda briefly exchanges glances with her (perhaps, we might think in this moment, in reaction to Giuliana’s movement). But the cry goes unacknowledged by everyone else, so Giuliana resumes her festive mood and reveals the egg in her palm, prompting the hilarity discussed in Part 19.

Later, when a doctor is seen boarding the recently arrived ship in the harbour, Linda suggests that he has come ‘to take away the person who cried out.’ Giuliana stands by in silence during the subsequent dialogue:

MAX: Who cried out?

LINDA: I don’t know… A little while ago, that cry [quel grido].

UGO: Sorry, what cry? Since the ship hadn’t yet arrived…

LINDA: What do you mean it hadn’t arrived?

UGO: No, it arrived when I went to stoke the fire.

EMILIA: But you’re crazy. It’s been there for half an hour.

MAX: Did you hear a cry?

CORRADO: I didn’t notice it.

LINDA: But I’m telling you… Is this a joke [Vogliamo scherzare]?

MAX: It must have been in your novel [romanzo].

LINDA: Do you think so [Dici]? Perhaps [Può darsi].

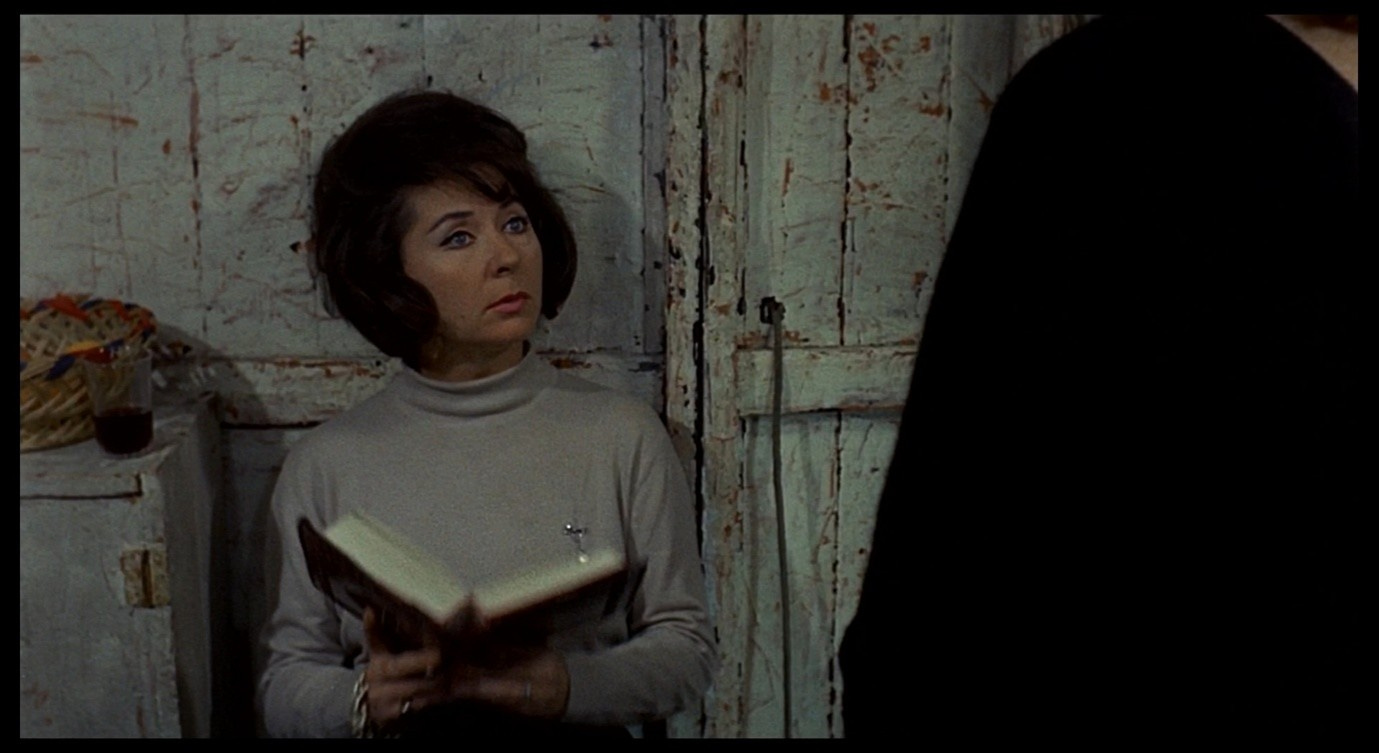

When Linda asks if her friends are joking, she literally says, ‘Do we want to joke?’ It is a sarcastic question about the collective decision that seems to have been made: ‘So we’ve all just decided to pretend we didn’t hear anything?’ When Max suggests that she heard a sound in her mind having read about it in her novel, she literally says ‘You say?’ The Italian word dici takes on an added resonance in the context of an argument over whether someone spoke (cried out) or not. Max’s utterance overwrites Linda’s and that of the anonymous crier, re-writing them as text that made its way from the novel into the reader’s mind’s ear. The cry was the stuff of a romanzo – ‘only a novel,’ as Jane Austen sarcastically put it10 – and Linda duly picks up her book, perhaps seeking evidence of the cry she heard or perhaps retreating into the realm of imagination to which her husband has consigned her. The Italian phrase può darsi literally means, ‘it could be given,’ and this is what Linda is doing: she could just give Max and the others their way and agree that there was no cry, so she does. Giuliana did the same thing when she heard the cry. Was it just in her head? Può darsi, since no one else heard it.

But after hearing this argument between Linda and the others – another act of hearing without responding – Giuliana decides, belatedly, to intervene. ‘I heard it,’ she says.

Ugo tries to nip this in the bud: ‘Let’s drop this story [storia], please. Cry or no cry [Grido o non grido], what importance does it have?’

Like Max, he tries to reduce the grido to the level of an insignificant storia. But to everyone’s alarm, Giuliana vehemently insists that it is important: ‘Someone cried out, it’s true, Linda didn’t make it up!’

‘Okay Giuliana,’ says Ugo in a placatory tone, and he begins to affirm that the cry was real, but Giuliana sees that she is being humoured and she says, all in one breath: ‘No you shouldn’t agree with me as if to say, as if I were a...’

Turning to Linda, she pleads with her, ‘Why did you say “perhaps”?’ ‘Did I say “perhaps”?’ asks Linda absently, looking up from her novel.

Not only was she unsure of having heard the cry, now she is unsure of having said she was unsure of having heard it. Then she looks out of the window and sees the yellow flag on the ship, indicating the presence of a communicable disease.

Something important is at stake in this dispute over the cry. Most obviously, it is a question of Giuliana’s grasp on reality. Like the tormented wife in Gaslight who sees the light fluctuating and hears the footsteps in the attic, Giuliana feels – she has been made to feel – that she can no longer trust her senses. The doctors have told her that she sees false connections between things that are separate (husband-son-job-dog), and we have seen her gazing at slag heaps, pools of effluent, and passing ships as though there were something terrible in them that remains invisible to the eyes of the well-adjusted. When she hears the cry, we know why she does not remark upon it: clearly, she does not want the others to find out that she has heard something they haven’t. When she tells Ugo not to speak to her ‘as though she were a...’ the screenplay notes, ‘She interrupts herself as though her own words, especially those that remain unsaid, have terrified her.’11 To be accused of ‘just hearing things,’ or to be patronised as though she were incapable of realising that she is ‘just hearing things,’ is to be treated like an insane person, and Giuliana is terrified of being insane or being thought insane.

However, ‘insanity’ is a reductive term here. As we have seen before, the problem may not stem from what Giuliana is, but rather from how she relates to the world around her, or how it relates to her. If the cry in the fog had been heard only by us and Giuliana, we might think that she had imagined it, and that we were sharing her deluded perception. The world around her is not really blurred, as it appears to be when she wakes up from her nap in the red room, but we see it that way because she does (more on this later). When we find out that Linda also heard the cry, this validates it – for Giuliana and for us – as a phenomenon that ‘really happened,’ and when Ugo and Max nonetheless insist on its unreality, and when even Linda seems to comply with them, this alters the stakes of the conversation. ‘There is something terrible in reality,’ Giuliana will say later, ‘and I don’t know what it is. No one will tell me.’ The cry denotes something terrible, and it is ‘in reality’ because at least one other person heard it…and yet no one but Giuliana will acknowledge it.

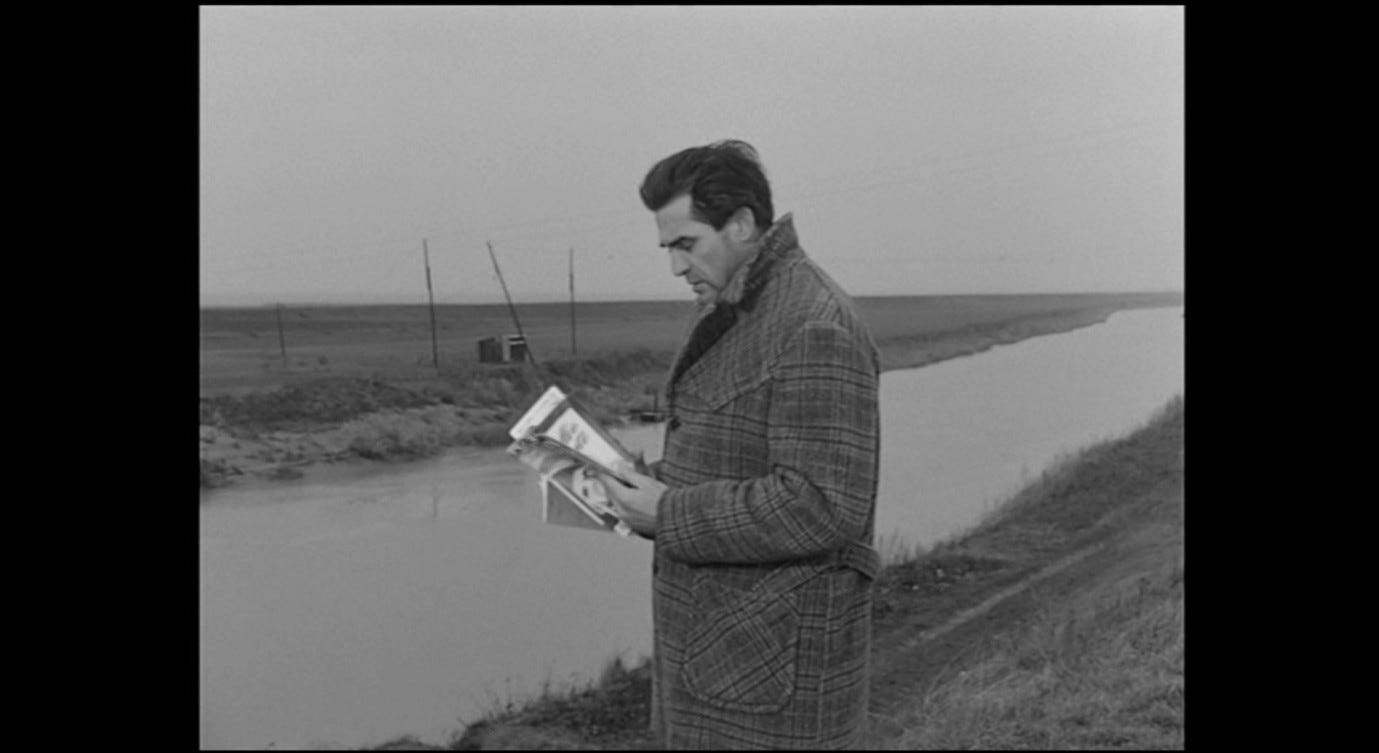

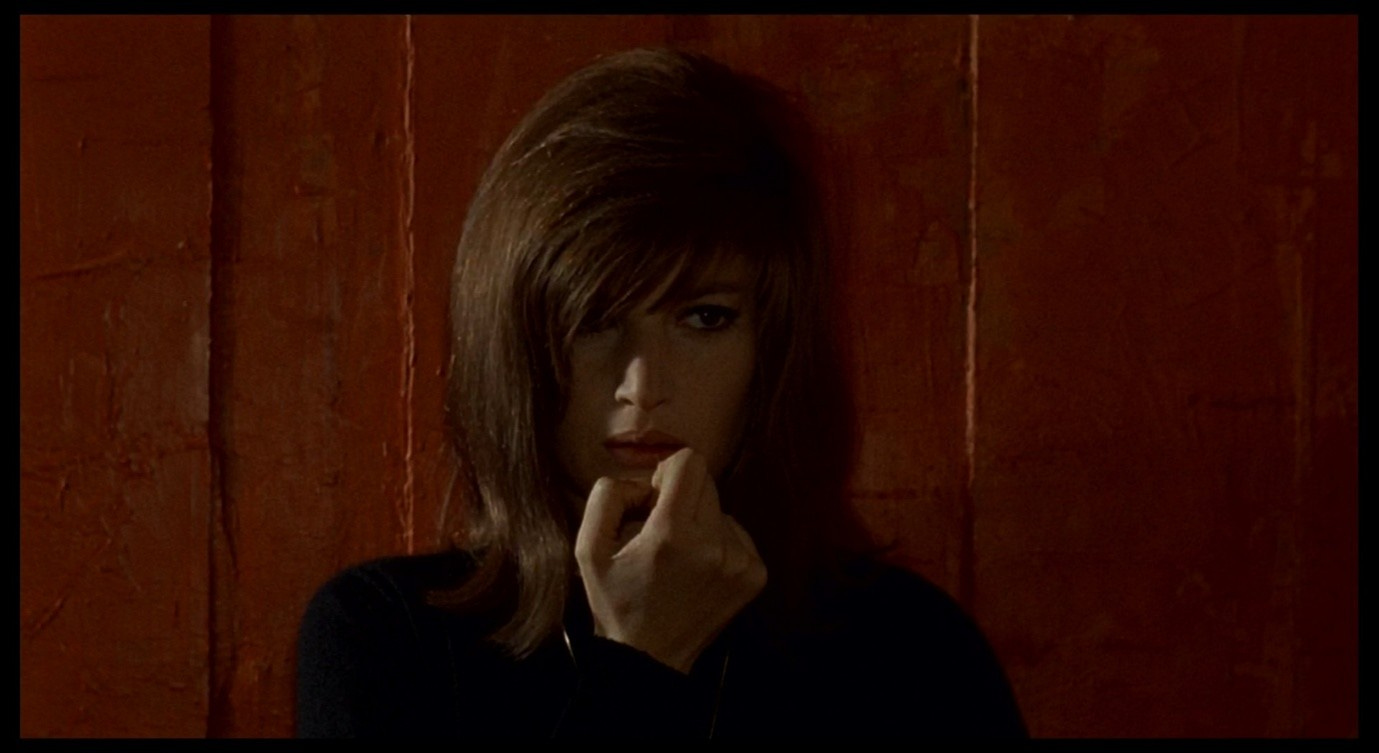

In Il grido, the titular ‘cry’ seemed to represent something terrible but ambiguous about reality, and about human relationships in particular. On the most superficial level, that film is about a man who loses the attachment that defines his life – his common-law marriage to Irma, with whom he has a daughter – which ends abruptly the moment her husband dies. Like the illicit relationship in Story of a Love Affair, Aldo and Irma’s connection persists only as long as there is an obstacle in its way. Once the inconvenient husband is gone, the emptiness of the affair becomes apparent. By the end of the film, Irma has established a more stable and respectable home, with a new (more legitimate) husband and child.

Il grido is built around the motif of feelings dying out and giving way to a sense of shame and futility. In the course of Aldo’s odyssey through a series of erotic encounters, he digs deeper and deeper into the malattia dei sentimenti. With each disappointment, Aldo murmurs the name ‘Irma’, but this is not simply a cry of unrequited love. The grido in this case responds to the terrible but unnameable thing that was exposed by the break-up with Irma. It has something to do with the transience and ephemerality of the love that seemed to exist between them, but that now seems never to have existed at all. Sam Rohdie comments on the omnipresence, in this film, of the Po river,

whose horizons, mist, fogs, changing tones provide not only a landscape for the emotions of Aldo but a play of alterations in shapes, and a tenuousness of mood and in life itself.12

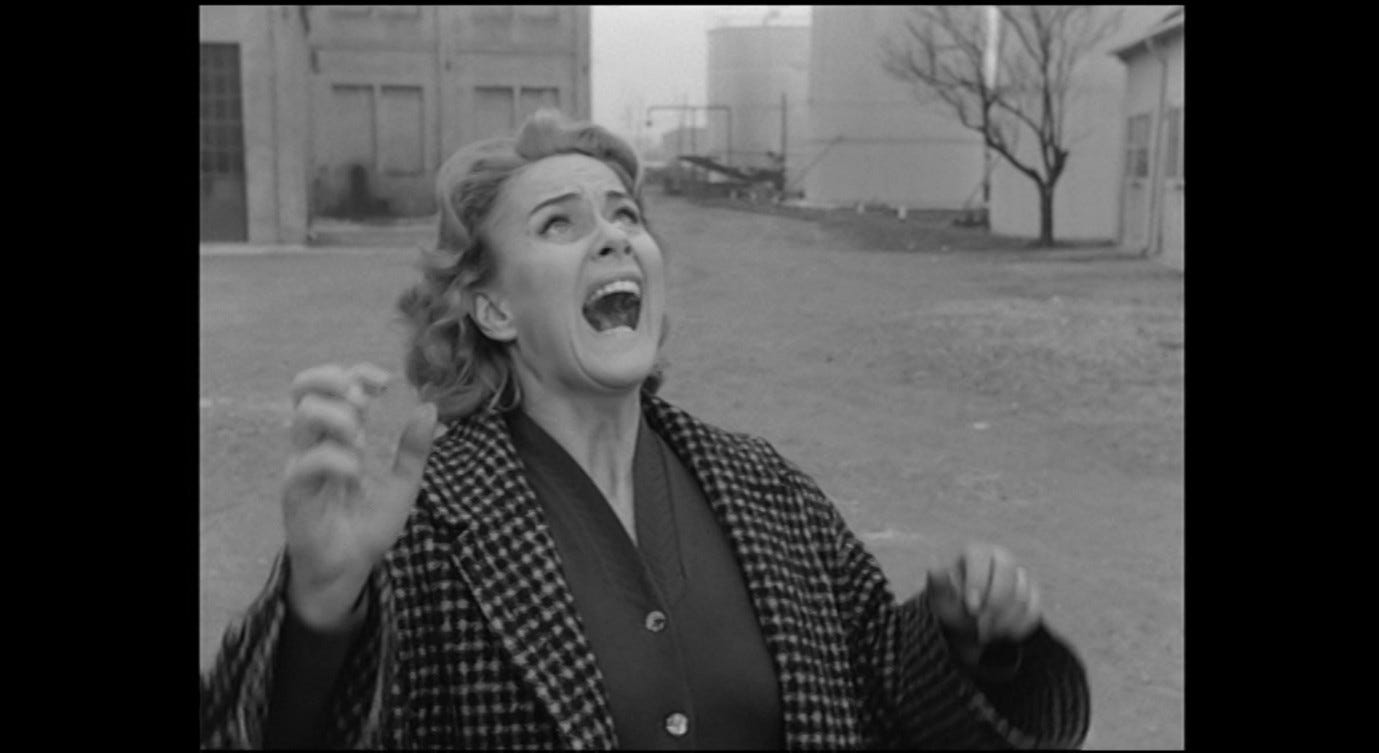

At the end of Il grido, Irma watches Aldo climb the refinery tower where he used to work. When he reaches the top, he waves at her and then – apparently losing his balance – falls to his death. As he falls, Irma screams, and her scream cuts off abruptly when he hits the ground. She is screaming in horror at Aldo’s fall and death, at the unknowability of its cause (accident or suicide), and at the impermanence of her own feelings: even the feeling behind this cry lasts only as long as it takes for a human body to fall to earth.

As she looks down at Aldo’s now-lifeless body, though she is still visibly upset, Irma is calm and collected. We get little sense that this incident will have a lasting impact on her, or that it should have such an impact.

The film does not suggest that Aldo’s life was important or worth remembering. Part of what makes Il grido so powerful is that it is a film about nothing, about a man realising he is nothing, about a certain perspective on life that makes life itself seem like nothing. Even to wave at another person is to overstate how connected we are. Giovanni Fusco’s occasionally sentimental score strives for an unwarranted degree of pathos, one that Aldo himself would probably sneer at. Some of Antonioni’s other films, including Red Desert, protest against this nihilism, or at least mourn it, but there is something bracing about the cold-eyed, hard-nosed way in which Il grido, Blow-Up, and The Passenger embrace this sense of nothingness.

In an un-filmed scene from L’avventura, one character speculates about Anna’s disappearance: ‘Maybe she simply drowned.’ Claudia responds, ‘Simply?’, and the characters look at each other in dismay. ‘This is it,’ commented Antonioni, ‘This dismay is the meaning of the film.’13 The dismay he refers to is essentially the same thing as the cry in Il grido and in Red Desert. In all three cases the dismay or the cry relates to death or mortal danger – the cry from the fog in Red Desert sounds like someone dying – and there is something terrible about the simplicity, mundanity, and insignificance of death in each case. Claudia might watch Il grido and ask: how can a person’s life mean so little, and end so bathetically, as Aldo’s does? How can the vanished Anna be written off so easily as having ‘simply drowned’? How, in Red Desert, can the cry of a dying man occur next door to some bourgeois twits having a frivolous quasi-orgy, and not even be noticed or acknowledged?

For Max and Ugo to deny this reality, or to deny that it matters whether the cry was real or imagined, means more than just questioning Giuliana’s sanity. It means that even the ‘dismay’ felt by the characters in L’avventura no longer has a place in this world. It would be like Irma not noticing that Aldo has fallen from the tower, not crying out, not even saying that he ‘simply’ fell – not saying anything at all. Millicent Marcus argues that the controversy over the cry is less about what is ‘true’ and more about human empathy:

[Giuliana grants] importance not so much to this proof of her sanity as to the human suffering betokened by the cry. Had the contested sound been a bell or a horn, she probably would not have bothered to insist, but a cry of pain or alarm which falls on the deaf ears of her companions proves once more their ruling defect – the failure of empathy that prevents them from imagining or participating in another’s plight.14

Marcus persuasively argues for the importance of this theme in Red Desert, citing other failures of empathy throughout the film. Giuliana’s problem has been described, by her husband, not as insanity, but as a failure to get in gear (ingranare). Later, Giuliana will describe it as a failure to re-insert herself (reinserirmi) into reality. But perhaps she does not fit into one reality because she inhabits a different one; perhaps she is the only recognisable human being left in her world. We might think of Antonioni’s use of the phrase si inserisce in ‘That Bowling Alley on the Tiber’, to describe how the murder fits into a social context where atrocities have become commonplace; a culture whose ‘ruling defect,’ as Marcus puts it, is its inability to ‘imagine or participate in’ human suffering. Marcus’s phrasing is significant given that ‘Bowling Alley’ was explicitly framed as a work of and about imagination, a way of imagining oneself elsewhere. Such creative acts mean stepping out into the periferia, and even, in the case of that story, imagining and participating in the mindset of a killer. This is not a sentimental conception of empathy; it is not about sympathising with or pitying the crying human, the murdered children, or their murderer. Contrary to Marcus, I think the ‘proof of sanity’ is extremely important in Red Desert, because in this context sanity is bound up with the perception of reality, including the kind of reality we access through fantasy and intuition. The social context in ‘Bowling Alley’ is insane. Antonioni’s fog-shrouded fantasy, even though it transports him beyond the literal truth of his surroundings, is bella and giusta because it sees the dead bodies, it hears the cry, and it thus disentangles itself from that sick social context. To mesh with the gears, to be inserted in reality, can also entail a detachment from and denial of reality.

Once the yellow quarantine-flag has been spotted on the nearby ship, it is Giuliana who takes this mortal threat seriously, insisting that they must all leave. But like the previous acts of escape around which the daytrip sequence is structured, this one leads to new dangers: the characters plunge into the fog from which the unearthly cry and the diseased ship originated. We see them running down the pier, with the ship and its yellow flag towering behind them. They seem to be getting clear of the enveloping fog, but in the next shot (from the reverse angle) they are running directly into another fog bank.

We are reminded of the sequence in the factory courtyard, in which Ugo and Corrado watched as a cloud of steam quickly took over the world and then subsided even more quickly (discussed in Part 8).

It is a suggestive visual metaphor for the transience, displacement, and somewhere-elseness that define the malattia dei sentimenti. All these features of Giuliana’s environment – the disease, the effluent, the fog – whether directly related to industry or not, cumulatively embody the multi-faceted sickness that afflicts her from within and without.

Giuliana has no sooner reached the safety of her car than she realises she must return to the shack to retrieve her purse, which eagle-eyed viewers may have noticed her dropping on the steps as she looked around in confusion.

However, she is too scared to return to the quarantined area herself, and she cannot bear to send either Corrado or Ugo.

An ambulance speeds down the pier towards the ship, underlining the potential risks of following in its wake; by definition, it is going to where the danger is.

When Corrado moves as if to run after it, Giuliana stops him, and they both turn around to face the rest of their party. As Giuliana stares at the others, they stare back at her, completely impassive and increasingly motionless.

From this point on, the encounter plays out across 10 shots:

Shot 1: We see Corrado and Giuliana, from behind, positioned in the foreground. Some distance away, we see Ugo and Mili (positioned between Corrado and Giuliana), and Max and Linda (positioned to the right). The sound of a foghorn emanates from the other end of the pier. Ugo glances back at the others and the camera cuts on this action.

Shot 2: A series of medium close-ups now focuses on each character (with the exception of Corrado), beginning with Linda…

Shot 3: …then Max.

Shot 4: The series of close-ups is interrupted by a reverse-shot of Giuliana slightly adjusting her position. She appears to have let go of Corrado’s arm.

Shot 5: Then we have a medium close-up of Mili…

Shot 6: …and of Ugo.

Shot 7: Giuliana comes closer to the camera and surveys the group.

Shot 8: A set-up like Shot 1, but with the camera moved forward to exclude Corrado and Giuliana, as though to represent only her point of view. We watch as Ugo, Mili, Max, and Linda, now completely motionless, are consumed by the fog rolling in from the sea.

Shot 9: A reverse-shot of Giuliana surveying them once more and then walking towards the camera.

Shot 10: Cutting on this action, the camera reverts to the set-up of Shot 1: Giuliana disrupts the tableau by striding into the fog, towards her car. We hear the foghorn again.

Throughout the daytrip sequence, the adulterous ‘love triangle’ has developed through a series of awkward moments. Corrado annoys Ugo by asking him whether he came home to look after Giuliana following her accident.

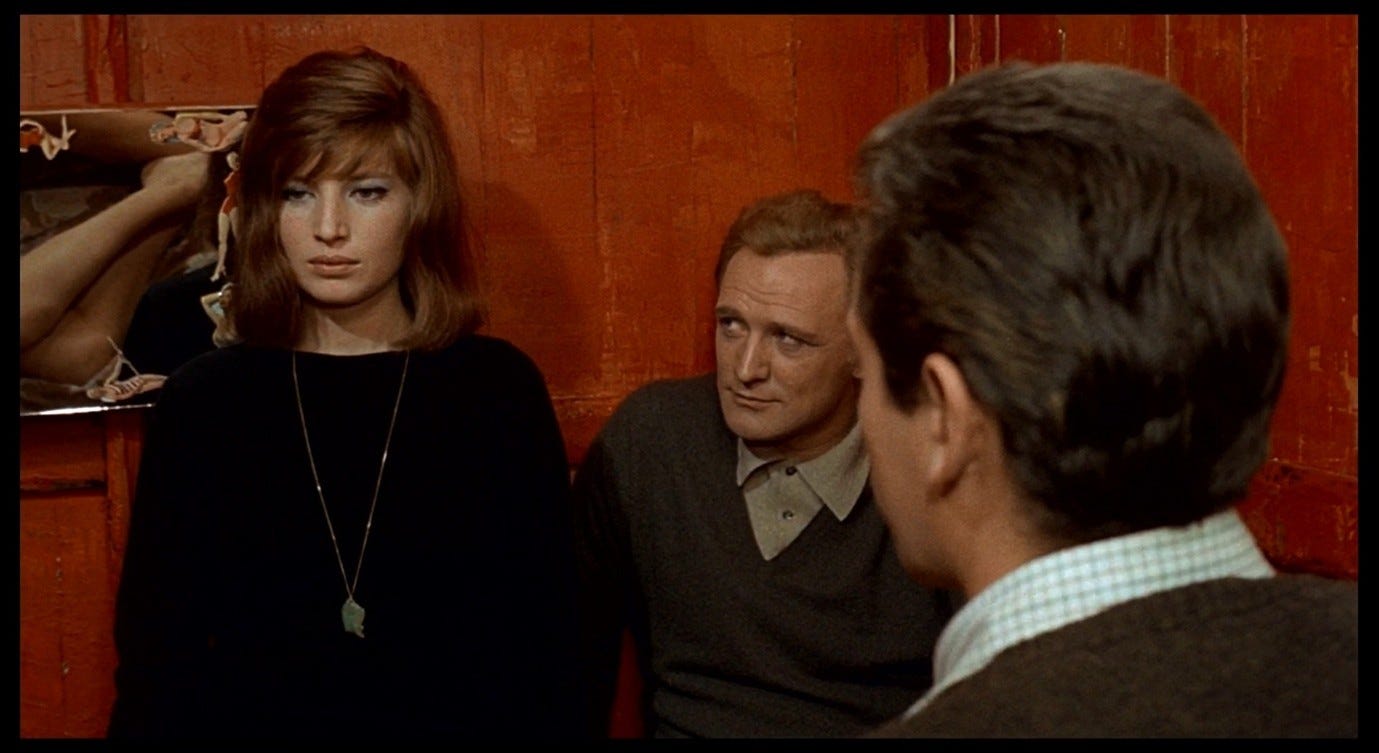

In the shack, there are various moments of physical intimacy between Giuliana and Corrado, or moments when he looks yearningly at her.

These moments are suggestive but carry little weight, and feel almost like perfunctory gestures towards the kind of will-they-won’t-they goings-on we might expect in a typical adultery drama. In Red Desert, the awkward moments do not escalate as we would expect them to. Ugo does not seem especially jealous (just mildly irritated by what he perceives as a rebuke), Corrado is not proactively hitting on Giuliana, and Giuliana herself shows no clear sign of being romantically interested in him.

When she grabs Corrado on the pier and they both turn to look at the others, the moment resembles another cliché of adultery drama: the telling sign of intimacy that makes the husband (and/or other onlookers) realise these two people are in love.

However, as in Mario’s apartment when Giuliana was mistaken for Corrado’s wife, the film refuses to hit the expected notes of shame and embarrassment. Ugo’s quick glance at the other ‘witnesses’ in Shot 1 might be the gesture of a humiliated cuckold, checking to see if his friends have noticed the same thing he has and perhaps also looking to them for support.

But what follows is stranger and more elusive. The close-ups on Linda and Max (Shots 2 and 3) might have shown them looking embarrassed, perhaps glancing at Giuliana, Ugo, and each other as though unsure of how to deal with the situation. Instead, these two stare impassively into the middle distance. There is little to no sense that they are making eye-contact with Giuliana or Corrado.

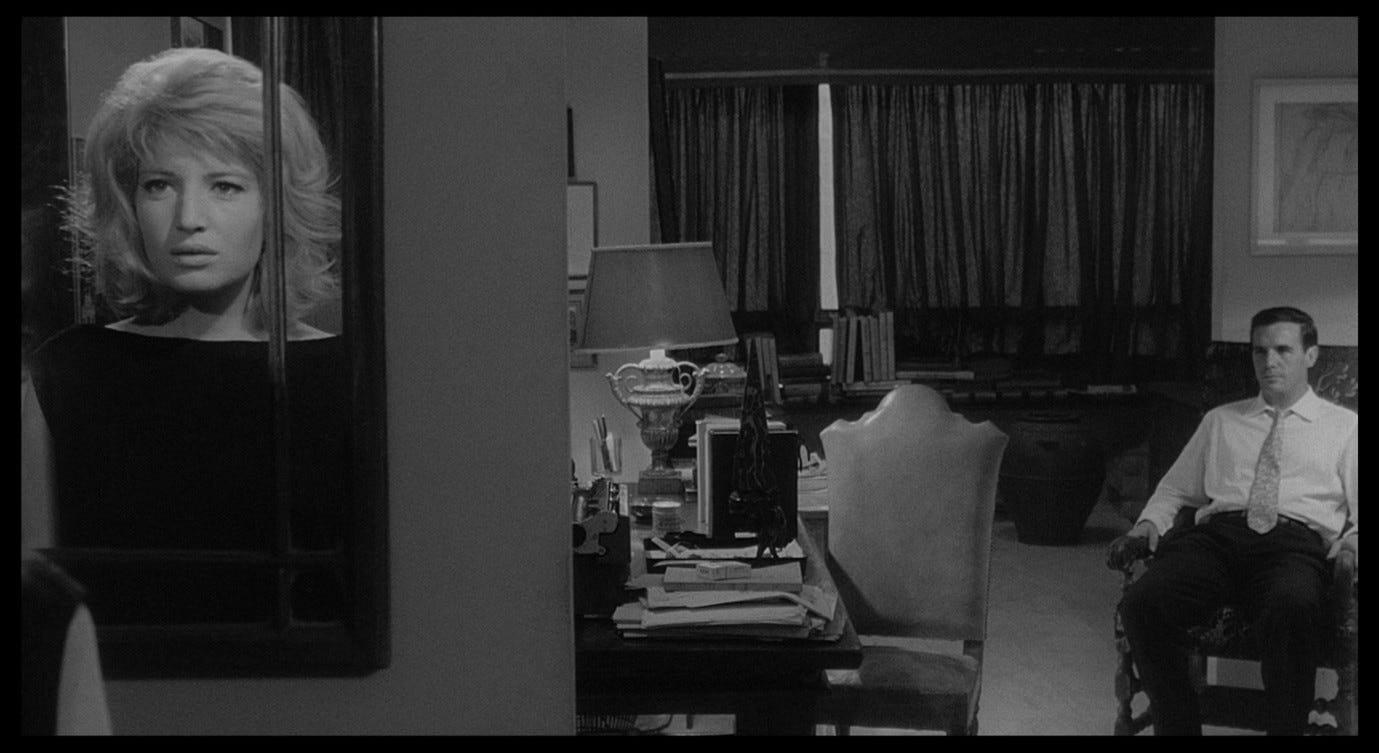

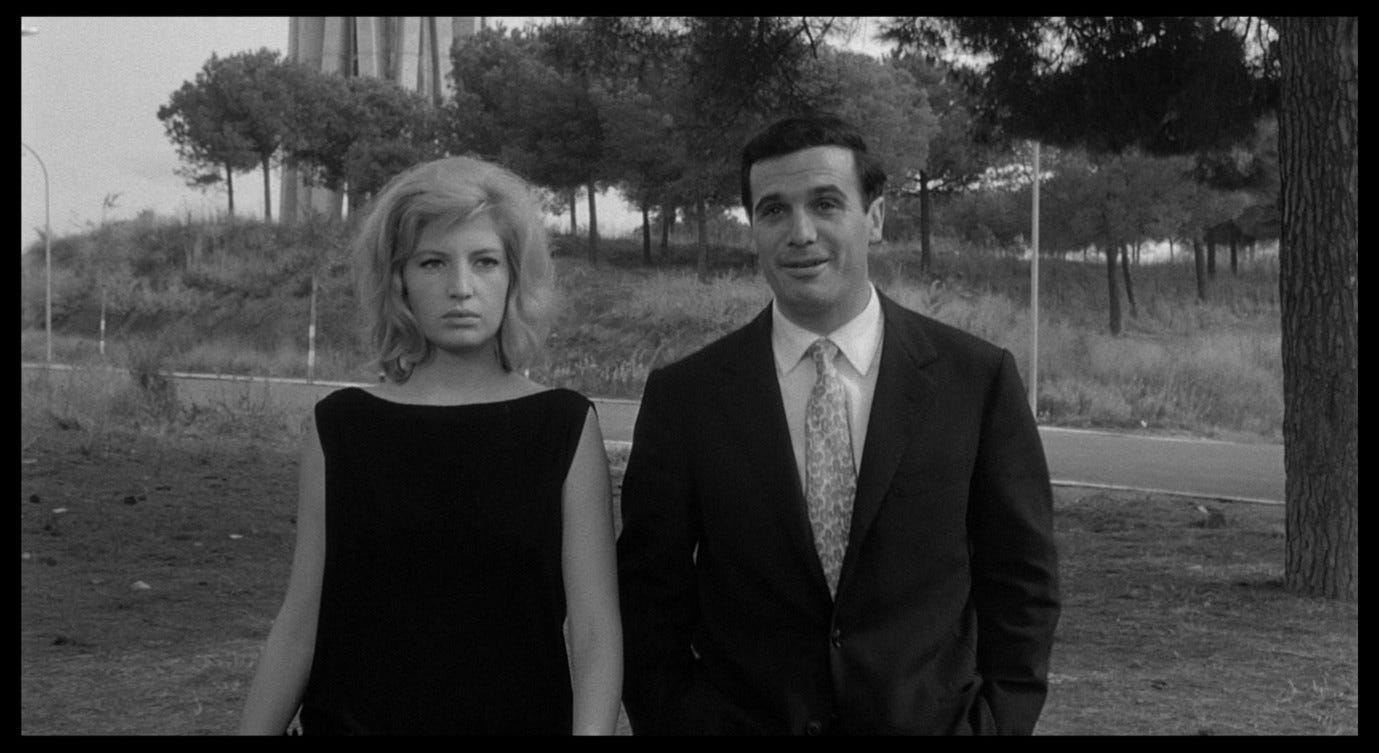

They resemble Riccardo in the opening scene of L’eclisse, who sits unnervingly still in an armchair, staring ahead like a robot that has been switched off.

That scene was also a variation on a melodramatic cliché – the break-up argument – rendered surreal and unsettling by having all the emotion drained out of it. Riccardo has gone into standby mode until the moment comes for his next pre-programmed speech and actions. Minutes later, he malfunctions and behaves as though the break-up had never happened, strolling alongside Vittoria and holding her hand. Her unnerved reactions are comparable to Giuliana’s when staring at her fog-shrouded friends.

In Shot 4 of the fog sequence in Red Desert, the reverse-shot of Giuliana’s reaction (to Linda and Max) isolates her, de-emphasising the relation between her and Corrado.

This moment is no longer about those two being seen by the others, it is about the others being seen by Giuliana. Just as they do not look like characters witnessing an illicit relationship, so she does not look like a woman caught cheating on her husband, sharing the awkward moment with her equally embarrassed lover. As she looks from right to left, we see the next two figures, Mili and Ugo (Shots 5 and 6). These two are just as inscrutable as Linda and Max. Mili stands at a 45-degree angle to the camera as though posing, not exactly looking at anyone or anything, but simply preparing to be looked at. Ugo looks head-on, is a little closer, is photographed in even softer focus than the others, and is more obscured by the fog, his typically blank stare becoming almost invisible as the vapour consumes it.

It is Ugo that Giuliana seems to be looking at so fixedly in Shot 7, as she moves towards the camera.

At first glance, her face too is blank – the make-up and the shadows around her eyes are very pronounced, making them almost seem painted on – but then she changes position and her eyes move as though searching for or trying to read something.

Her slightly open mouth suggests that she is reflecting, on the verge of a revelation, in contrast to the closed mouths of the people she is looking at. We have no idea what they are feeling or thinking, if they are feeling or thinking anything, but we understand that Giuliana is afraid. Whatever frightened her about the cry in the fog, or the denial of that cry, or the diseased ship, that frightening thing looms larger than ever at this moment.

Her eyes move from Ugo back to the other three figures, and at this moment we cut to Shot 8, seeing exactly what she sees. The stasis in which the four figures are trapped is more conspicuous now that they are all in frame at once. Their arrangement seems more artificial, more like a painting – one whose background is unfinished and (as the shot progresses and the fog comes in) one that is being wiped out by the painter, replaced with a Rothko-like wall of pale grey. Our world seems to be on the precipice of fading out of existence. The figures who are farthest away disappear first, while the one closest to Giuliana – Ugo – remains visible the longest, though he too is just about to vanish when we cut to Shot 9, in which Giuliana’s gaze searches for some remnant of these people.

Unable to find them, like Anna in L’avventura telling Sandro ‘I don’t feel you anymore,’ Giuliana is overcome with emotion and runs – then drives – head-first into the fog, into oblivion. This gesture, like the highly artificial image Giuliana has just been gazing at, feels symbolic. As her car speeds into the fog, it is as though she were trying to make her world fade out of existence for real, like a person embracing death in order to end a nightmare.

William Arrowsmith reads this sequence as a premonition of Giuliana’s later speech about the ‘separateness’ of human bodies, but also as referring back to earlier images in the ‘shack’ sequence. The characters in the fog are seen

not huddling together in a warm, sleep-blurred group in the red-walled shack but suddenly there, seized in individual isolation before dissolving into the anonymous fog. For the first time she sees them alone and then as a group, ‘alone’ together, discretely, in their separation from each other and from her; then she sees them together, linked by a common extinction, all slowly folded in the fog.15

The sequence in Max’s shack can be divided into two parts, each of which has its own typically disorienting establishing shot. The first begins with a close-up of the embers in the stove, before introducing Mili’s feet.

The second, which Arrowsmith refers to, begins with an out-of-focus image of the characters in the red room, blurred together and napping. Then Giuliana’s head enters the frame as she wakes up and looks at her friends.

Arrowsmith describes the characters as ‘huddling together in a warm, sleep-blurred group,’ but the reverse-shot of Giuliana suggests that she finds this image disturbing – Ugo has to repeat himself to get her attention.

There is indeed a dramatic contrast between the blurred-together people in the shack and the separated people in the fog; but there is also a blurring-together of the effects these images have on Giuliana. We can trace a progression from one phase of this scene to another. It begins with the stove and the introduction to Mili (who is then associated with Giuliana). By the time Giuliana wakes up from her nap, the way she sees these people is coloured by the experience of the various flirtations and harassments that take place in the red room. Between then and the lost-in-the-fog sequence, she overhears Mili’s comments about Max’s predatory behaviour, participates in the plank-breaking and the shame that follows in its wake, and argues with the other characters over the anguished cry from outside. Giuliana’s escalating anxiety is not only provoked by her sense of how separate and lonely people are. As Arrowsmith says, it is the simultaneity of ‘alone’ and ‘together’ that accounts for the impact of the fog-shrouded tableau. Why, for example, is Linda’s può darsi so upsetting? It is not because of her separateness from Max, but because Max can so easily influence her perception of reality, and because Giuliana sees here an echo of something in her own marriage. The encounters with various kinds of exploitation and emotional sickness in the shack (and in earlier scenes) have built towards this moment on the pier – in a sense, it is from all these encounters that Giuliana is trying to escape when she drives away.

Seconds after her flight into oblivion, Giuliana is discovered at the end of the pier, her car poised on the slope that leads into the sea.

The fog is no longer so pervasive, the foghorn (which had been distant and spectral before) is now loud and close, and everything is embarrassingly visible. This is the embarrassment of attempting a symbolic gesture and ending up in a literally and mundanely inconvenient position. Ugo is exasperated by Giuliana’s inconsistent behaviour: first she was terrified of the diseased ship, now she drives straight towards it? He (apparently) fails to register that this might have been an abortive suicide attempt, and Giuliana seems to want to forestall this realisation when she begs Ugo, in a frenzied tone and with her hair flying about in the wind, to believe that she was trying to go home, that she simply took a wrong turn.

But if she were going home, why would she have driven off without Ugo? And if she simply took a wrong turn, why would she be this upset, rather than just mildly ashamed by her own absent-mindedness?

Linda, who heard the cry in the fog but talked herself out of having heard it, is a significant extra character to have as a bystander in this scene (Max and Mili have stayed with the cars). Linda says nothing but bursts into tears; we perhaps infer that she recognises Giuliana’s suicide attempt, but that she cannot verbalise this thought or the emotions that come with it. Giuliana, trying to justify herself to Ugo, interrupts herself to lash out at Linda: ‘What do you have to cry about [Cosa hai che piangere tu]?’ Linda duly attempts to rein herself in and stop crying.

There is no more dialogue for the last few seconds of this painful scene. We watch from a distance as Giuliana turns from Linda to stare at the sea she almost drove into.

Corrado stands close behind Giuliana as he did during the lost-in-the-fog sequence, grimacing in the severe weather and looking from one person to another. He is his usual inscrutable self, neither as sympathetic as Linda nor as judgemental as Ugo, but simply present and attentive to what is happening. We are primed to think that he is assessing the state of Giuliana’s marriage, especially in the light of her husband’s response to her illness, but we still do not know for certain whether he wants to help Giuliana or just have sex with her.

The hard cut at the end of this sequence is the final ‘escape,’ mercifully transporting us away from the pain and embarrassment. Although she does not take her own life, there is something of Aldo’s fall in Giuliana’s drive to the end of the pier. It is a cry of pain and despair that does not amount to anything; it is humiliating for everyone involved. There is something especially telling about the wry joke on which the scene ends. Giuliana has tried to express an emotion – a very deep and intense emotion – but she is not crying and Linda is. Even the communication of feelings has been appropriated by the wrong person. Giuliana’s question (‘Why are you crying?’) underlines the absurdity of the crying gesture being attached to the person who is not upset, while the person who is upset cannot find any words or gestures to express herself. This tableau is the bathetic mirror-image of the more dramatic one in the fog a minute earlier: this too represents the ‘something terrible,’ which consists not only in the incommunicability of feelings but also in their triviality. Perhaps (that word that so bothered Giuliana) when someone cries out in the fog, it really doesn’t matter whether anyone hears it or not.

Next: Part 21, Corrado’s philosophy.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘That bowling alley on the Tiber’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 69-74; p. 72. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Quel bowling sul Tevere’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 79-86; p. 82

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Quel bowling sul Tevere’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 79-86; p. 81. Arrowsmith translates this as ‘Experience teaches me that when an institution has its own beauty, it’s a good one’ (p. 71). The original text says intuizione, so ‘institution’ is a mis-reading or a typo; I am not sure that ‘has its own’ is there in the original text; and ‘good’ is perhaps a more elegant translation of giusta but in this case I read it as meaning ‘right’ or ‘correct’.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Quel bowling sul Tevere’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 79-86; p. 84. Arrowsmith translates the first sentence as: ‘In Ferrara, where I was born, the winter fog moves in so thickly you can’t see three feet away, and this was how, in my imagination, it happened’ (p. 74). In this version, the ‘it’ seems to refer to the action of the story, as if to say that the man killed the children while surrounded by (metaphorical?) fog. But I think Antonioni is referring to the way the story came to him. The original text reads: ‘Come su Ferrara, dove io sono nato, d’inverno scende la nebbia talmente fitta che non si vede a un metro di distanza, cosí è accaduto alla mia imaginazione.’

Alighieri, Dante, The Divine Comedy, Inferno, Canto 1, ll. 2-3; text from World of Dante.

Alighieri, Dante, The Divine Comedy, Inferno, Canto 3, ll. 112, 118; text from World of Dante. The lines mean, ‘As in autumn the leaves fall […] So they [the souls] go across the dark wave.’

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘That bowling alley on the Tiber’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 69-74; p. 74. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Quel bowling sul Tevere’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 79-86; p. 84

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘That bowling alley on the Tiber’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 69-74; p. 74. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Quel bowling sul Tevere’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 79-86; p. 85

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘That bowling alley on the Tiber’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 69-74; p. 74. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Quel bowling sul Tevere’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 79-86; p. 84

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘That bowling alley on the Tiber’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 69-74; p. 72

Austen, Jane, Northanger Abbey, Chapter 5. Text from Project Gutenberg.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 473

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 26

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The Adventures of L’avventura’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 78-81; p. 81

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), pp. 198-199

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 87