Everything That Happens in Red Desert (43)

Something terrible in reality

Towards the end of Red Desert, Giuliana makes two pronouncements that seem to encapsulate (respectively) her problem and her way of coping with that problem: ‘There is something [qualcosa] terrible in reality,’ and ‘Everything [Tutto quello] that happens to me is my life.’ They are definitive statements that resonate through the entire film, but they are also characterised by vagueness and uncertainty. The qualcosa remains unknown, tutto quello means both ‘everything’ and ‘whatever,’ and the film itself will be inconclusive. It therefore seems appropriate that both statements are (at least partly) rooted in Robert Musil’s long, confusing, unfinished novel The Man Without Qualities, which is quoted in La notte and referred to in several documents relating to Red Desert in the Antonioni Archive.1 This novel is a treasure trove of Antonioni-isms, but it has a special relevance to Giuliana’s comments in the present scene, and to the clash between her perspective and Corrado’s.

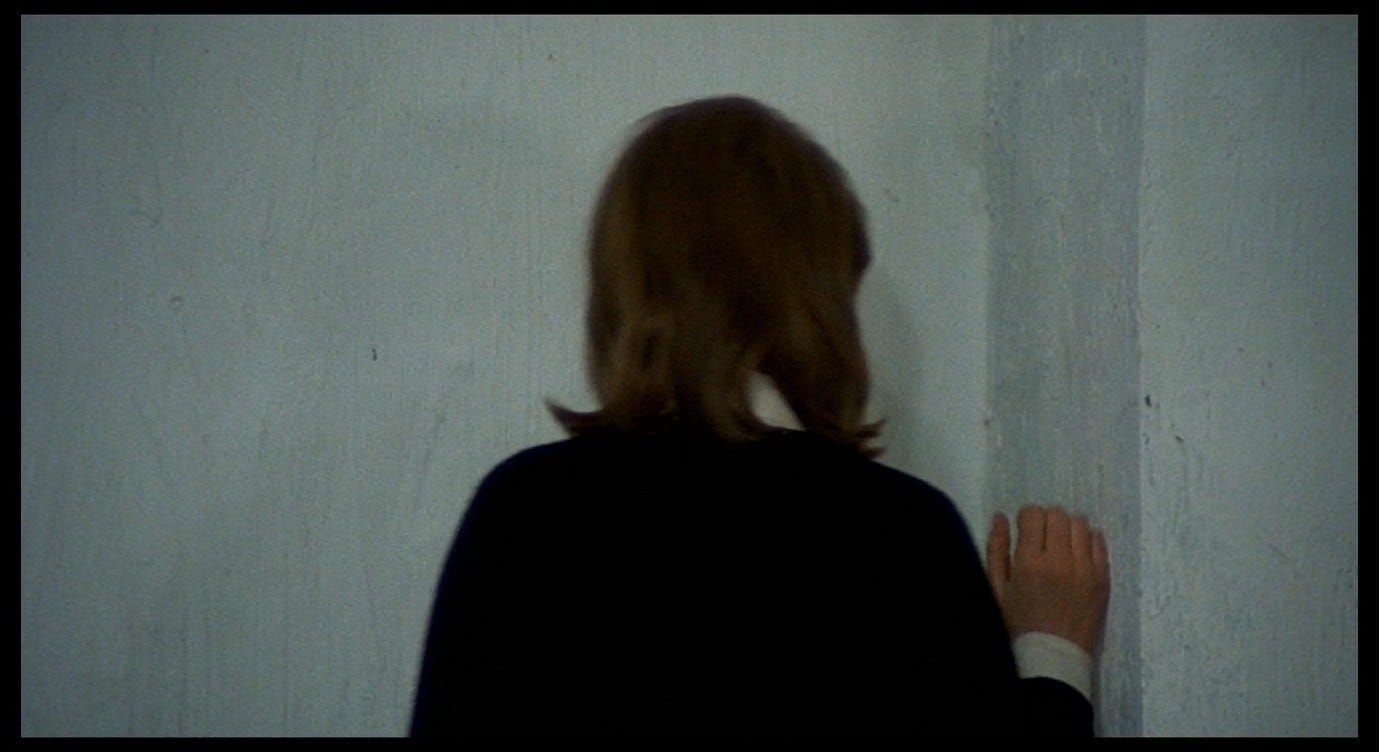

After her frenzied cry of ‘I can’t take it anymore!’, Giuliana suddenly falls still and silent. The bleakness of the following shot, in which she is framed diminutively against the white wall, is devastating.

In Part 42, I mentioned that she was framed in the same way when she asked Corrado what she ought to sell in her shop. What she says now is a comment on what she was trying to do then:

I have done everything to reinsert myself [reinserirmi] in reality, as they say [dicono] in the clinic. One would say [Si direbbe] that I have succeeded. I have even succeeded in becoming an unfaithful wife.

For an instant she meshes her fingers together, then pulls them apart as she says reinserirmi, before bringing them back together again in a tangled, twisted mess. The gesture compares the process of ‘reinsertion’ to the pulling apart of her self; it also compares it to the distortion of that self by the attempt to jam it back into place.

Near the start of the film, when describing Giuliana’s illness to Corrado, Ugo said that even after her month-long stay in the clinic, ‘the gears still don’t mesh [ancora non riesce a riingranare].’ He held his hands up, with the fingers positioned to resemble the gears of a mechanism rotating but failing to mesh.

As I noted in Part 9, the Italian verb inserire is also used to describe putting a car in gear. Ugo’s hand-gesture indicates gears outside the head, trying to attach themselves to the temples in order to put the brain in gear, but it also suggests gears inside the head trying to mesh with each other. The problem, he is saying, exists both within Giuliana’s mind and in her failure to align with the world around her. When she says that she has tried to reinserirmi nella realtà, she stands in a corner, in an alcove. Giuliana often inserts herself into these demarcated spaces as though taking refuge in them, but also perhaps in an attempt to fit in with the physical world. She is always restless in these alcoves, however, and in this case the word realtà seems ironic when she is standing against this un-formed blank surface. If she fits into anything, it is a void, a state of non-existence in defiance of reality.

Giuliana is being ironic when she goes on to affirm her ‘successful’ reinsertion into reality. She twice uses the verb dire to invoke an external voice, first the collective voice of the clinicians (from whom she derives these terms of ‘reinsertion’ and ‘reality’) and then the indefinite third-person voice that would judge her reinsertion to be successful. When she invokes these voices, we see Corrado approach her, coming into focus as he steps forward, reinserting himself into her reality (so to speak).

In the reverse-shot of Giuliana, Corrado now occupies the right-hand side of the frame, but Giuliana looks away from him, into the middle distance, as she fidgets with her wedding ring and comments on her ‘success’ in becoming an unfaithful wife.

‘You shouldn’t think such things, Giuliana,’ Corrado says, looking down (with an air of embarrassment) at the floor and then up at her. Her comments are, as Ugo might say, not decorous.

In a medium close-up, Giuliana holds eye-contact with him as she responds with bitter irony, ‘Sure, it’s enough not to think about it [basta non pensarci]. Beautiful conclusion [Bella conclusione].’

Giuliana seems fully aware of the external standards and conventions to which she is supposed to adhere, and of the voices that communicate these standards. She is openly critical of the way these voices paper over the ‘reality’ into which she is supposed to insert herself. There is a normal way of feeling and talking about the avventura you have with your husband’s friend. If only she would not see that sexual encounter as she did in the hotel-room scene, and not brood over her condition as she does now – if only, in short, she would ‘not think about such things’ – she might be spoken of as guarita, cured, a successful case-study. What a bella conclusione that would be; a happy ending to the story.

She takes a few more steps into her alcove, touches the wall for a moment, then leans her back against it and looks sidelong at Corrado.

She is as fully ‘inserted’ into this space as she can be, cornered with no hope of escape, but her expression is now calm and confident. She implicitly rejects Corrado’s advice by expressing the most unthinkable thought, and by protesting against the failure of that generalised external voice to engage in any kind of dialogue with her about it:

There is something terrible in reality [qualcosa di terribile nella realtà], and I don’t know what it is. No one will tell me. Even you haven’t helped me, Corrado.

Perhaps, after all, the void Giuliana stands in is more real than the solid world she is being urged to return to. Perhaps she is the one who is most truly nella realtà at this moment, and the only one who will talk about it. In a sense, she herself (da sola) is that terrible thing, and this time no one can tell her what she is, or train her to explain this to her self.

During the first part of the ‘terrible thing in reality’ speech, we see the back of Giuliana’s head (in focus) juxtaposed with Corrado’s impassive face (out of focus), seen at a 45-degree angle.

He has spoken his last line of dialogue in the film, and in this shot he is reduced to a closed-off, inscrutable emblem of the world that will not talk to Giuliana. He has just told her she should not think such things, and now he is silent; it is enough (basta) not to think or to talk. There is a chilling blankness about Corrado in this scene. All his genial charm, his attempts at friendliness or seduction, are gone. Is this because he has got what he wanted and lost interest, because Giuliana has in some sense found him out, or because she is beyond being helped (at least by him)?

Corrado too represents the ‘terrible thing in reality.’ By making Giuliana into an ‘unfaithful wife’ – a phrase she utters in, I think, a tone of resentment rather than guilt – he has facilitated the successful reinsertion she just described, while reaffirming the lack of autonomy that sustains her illness. The approved recovery process, and the standards by which one is judged to be reintegrated in reality, are terrible, and Corrado’s cold, intractable refusal to think or talk about this is terrible as well. The Italian phrase qualcosa di terribile marks the terrible-ness as a quality ‘of’ the something, an aspect that has been discovered within it. There is something in there, beneath the surface, that cannot be named, and ultimately the film suggests that it is terrible in large part because it is unnameable, because of the silence that surrounds it.

The prescription of not-thinking and not-talking about the problem at hand recalls Giovanni’s attitude towards Lidia at the end of La notte, when he refuses to acknowledge the rupture between them. This ending is obliquely foreshadowed by the literary debate earlier in the film, triggered by Roberto’s quotation of this passage (with minor alterations) from The Man Without Qualities:

We are living in an unphilosophical, dispirited age; it doesn’t have the courage to decide what is valuable and what isn’t, and democracy means, expressed most succinctly: Do whatever is happening!2

Giovanni retorts:

I know those words – they are by a writer I love – but said here, they horrify me a little. […] This man here said it with a certain complacency, while the author wrote it in despair.

In fact, in its original context the quoted passage is not as tonally straightforward as Giovanni suggests. The words are spoken not by Musil’s omniscient narrator, but by the pretentious quasi-intellectual Meingast. Later, when his protégée Clarisse confronts him with his own grandiose opinions, he no longer feels so invested in them:

‘And then there’s your marvelously contemptuous formulation,’ Clarisse cried, ‘that in modern life people only do what is happening anyway.’ Meingast stopped and looked down; one might have said that he was either inclining an ear or studying a pebble lying before him on the path, slightly to the right. […] ‘When you say, for instance, that one must decide against the lesser value for the sake of the higher value,’ she cried, ‘it means that there’s a life in an immense and boundless ecstasy!’ […] Meingast shook his head. Denial filled him on hearing this altered and impassioned version of his words; it was a startled, almost frightened denial.3

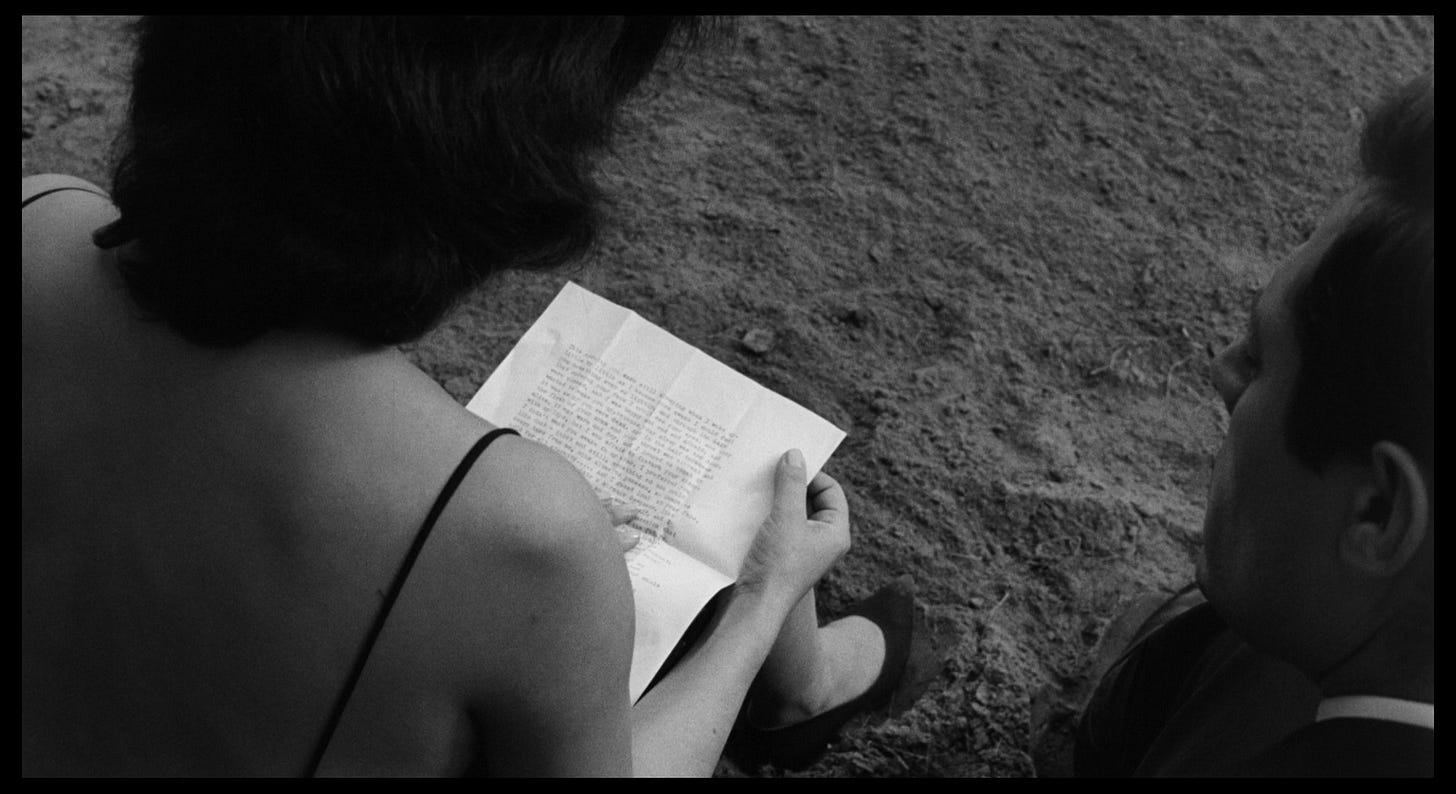

Meingast’s distracted gestures and denial of his own words make me think of Giovanni when Lidia reads out his old love letter and he fails to recognise it.

Both men are seemingly profound thinkers who turn out to have spoken (or written) complacently, without serious conviction. Ulrich, the protagonist of Musil’s novel, immediately recognises Meingast as a charlatan, but is himself often torn between the intellectual (and influential) role he finds himself playing and his internal sense of futility. In one passage, this conflict is figured in terms of a ‘doubling’ of Ulrich’s personality:

But while the Ulrich smiling at these reflections walked on through the hovering evening, the other had his fists clenched in pain and rage. He was the less visible of the two and was searching for a magic formula, a possible handle to grasp, the real mind of the mind, the missing piece, perhaps only a small one, that would close the broken circle. This second Ulrich had no words at his disposal. Words leap like monkeys from tree to tree, but in that dark place where a man has his roots he is deprived of their kind mediation. The ground streamed away under his feet.4

What horrifies Giovanni about Roberto’s quotation is (he says) its tone of complacency, as opposed to the alleged despair of the original, but a recurring motif in The Man Without Qualities is the complacent smile that covers a deep well of despair, the articulate man of letters who is, in his heart of hearts, a speechless wreck. Roberto, in La notte, barely speaks any words of his own. In one memorable scene, he talks to Lidia in his car, but his words are drowned out by the rainstorm.

By quoting Meingast at the party, he is holding up a mirror to Giovanni. He is saying, ‘You are like one of Musil’s fatuous, complacent intellectuals.’ Giovanni does not recognise this complacency as his own, just as he does not recognise his amorous platitudes when Lidia reads them back to him. He high-mindedly scoffs at the idea that anyone at this party could have read The Sleepwalkers, but he is the only major character in the film who seems not to have understood Broch’s or Musil’s work (see Part 30). He is like Meingast, fully absorbed in his own importance but incapable of living up to it, and incapable of facing his inner conflicts as Ulrich does. He talks easily, leaping from tree to tree, unwilling to connect with the dark roots down below.

The ‘second Ulrich,’ the less visible one who is consumed by pain and rage, comes into being at the level of those roots, but like Giuliana he does not find himself grounded or rooted as a result: ‘the ground streamed away under his feet’ just as Giuliana’s ‘second self’ (her friend in the clinic) lacked any firm ground to stand on. Musil’s novel revolves around this existential crisis, which is figured as a response to the very serious problem that Meingast describes so complacently. Something has happened to the age we live in, akin to the disintegration of values that Broch was describing around the same time, but seen here through the lens of Musil’s wry humour:

In Goethe’s world the clattering of looms was still considered a disturbing noise. In Ulrich’s time people were just beginning to discover the music of machine shops, steam hammers, and factory sirens. One must not believe that people were quick to notice that a skyscraper is bigger than a man on a horse. On the contrary, even today those who want to make an impression will mount not a skyscraper but a high horse. […] Their feelings have not yet learned to make use of their intellect. […] So it was no slight advantage to realize, as Ulrich did when barely out of his teens, that a man’s conduct with respect to what seem to him the Higher Things in life is far more old-fashioned than his machines are. […] Who could still be captivated by the thousand years of chatter about the meaning of good and evil when it turns out that they are not constants at all but functional values, so that the goodness of works depends on historical circumstances, while human goodness depends on the psychotechnical skills with which people’s qualities are exploited? Looked at from a technical point of view, the world is simply ridiculous: impractical in all that concerns human relations, and extremely uneconomic and imprecise in its methods; anyone accustomed to solving his problems with a slide rule cannot take seriously a good half of the assertions people make.5

The flip-side of this apparent complacency is a very Red Desert-esque feeling of self-annihilation:

‘What is left of me?’ Ulrich thought bitterly. ‘Possibly someone who has courage and is not for sale, and likes to think that for the sake of his inner freedom he respects only a few external laws. But this inner freedom consists of being able to think whatever one likes; it means knowing, in every human situation, why one doesn’t need to be bound by it, but never knowing what one wants to be bound by!’ […] [H]e had nothing but an ability to see two sides to everything – that moral ambivalence that marked almost all his contemporaries and was the disposition of his generation, or perhaps their fate. His connections to the world had become pale, shadowy, and negative.6

The advances of the 19th and early 20th centuries have exposed something terrible in reality, and something which will be further exposed by World War I (referred to in a throwaway line about ‘millions of dead men in the wake of a shattering war.’)7 We can see in the above passages some clear parallels with Antonioni’s comments in his Cannes statement (see Part 19) about our moral and emotional intelligence lagging behind technological progress, and with his interest in futurism and musique concrète (see Parts 3 and 4). Most importantly, The Man Without Qualities provides a model for how these meditations on contemporary life can be explored through vividly drawn human characters. In Ulrich’s agonised ‘What is left of me?’, his sense of un-boundedness and vague longing to be re-bound to something, and his ‘pale, shadowy, and negative’ connections to the world around him, we find a precursor to Giuliana and hints at the visual motifs that Antonioni will use to represent her experience.

Giuliana appears in other guises elsewhere in the novel, as when Musil’s narrator imagines the plight of a hypothetical person who goes against the grain of their ever-shifting environment:

‘What people are’ evidently keeps changing as rapidly as ‘What people are wearing,’ and both have in common the fact that no one, not even those in the fashion business, knows the real secret of who ‘these people’ are. But anyone trying to run counter to this would look silly, like a person caught between the opposing currents of an electric therapy machine, wildly twitching and jerking without anyone’s being able to see his attacker. For the enemy is not those quick-witted enough to take advantage of the given business situation; it’s the gaseous fluidity and instability of the general state of affairs itself, the confluence of innumerable currents from all directions that constitute it, its unlimited capacity for new combinations and permutations, plus, on the receiving end, the absence or breakdown of valid, sustaining, and ordering principles. To find a secure foothold in this flow of phenomena is like trying to hammer a nail into a fountain’s jet of water; and yet there is a certain constant in it. […] Something unstated is at work here. […] Something more is left unsaid.8

The comment about ‘those quick-witted enough to take advantage of the given business situation’ might prompt us to think of Max, the predatory industrialist in Red Desert who is always ready to swoop on a factory (or a woman) in crisis. Likewise, Musil’s dismissal of the problem of exploitation might make us think of how Max disappears, along with everyone else, in the fog that rolls in from the harbour.

Like Huguenau in The Sleepwalkers, Max is an adequate child of his era, going with the flow of those ‘innumerable currents’ amidst the general state of ‘gaseous fluidity and instability.’ No one could maintain their integrity or a sense of fixed identity in such a world, and yet Musil insists that there is some form of ‘constant’ at work here; like Giuliana, he sees something terrible in reality but marks it as ‘unstated, unsaid.’ As in Red Desert, the unspoken-ness is tied up in the powerful influence of norms and conventions:

[W]hen we feel that we can lay claim to every quality as naturally as to none; or when it seems to us that what happens is only semblances prevailing, because life – bursting with conceit over its here-and-now but really a most uncertain, even a downright unreal condition – pours itself headlong into the few dozen cake molds of which reality consists; or that in all the orbits in which we keep revolving there is a piece missing; or that of all the systems we have set up, none has the secret of staying at rest: then all these things, however different they look, are also bound up with each other like the branches of a tree, completely concealing the trunk on all sides.9

Like the tree described here, this sentence is intricate and tangled, rendering its meaning obscure. This is, after all, the feeling Musil wants to describe: myriad possibilities crowding in on us, all of potentially equal value, preventing the emergence of any clear sense of what ‘is’ (reality) as opposed to what ‘could be.’ The clause I want to emphasise here is the one about ‘life.’ Everything that happens seems determined by ‘semblances’ because of the way in which life pours itself into the ‘cake molds of which reality consists.’ Life itself, though, despite having the semblance of ‘here-and-now’ reality, is in fact an ‘uncertain and unreal’ condition. What we call reality is nothing more than a set of restrictive norms within which we are used to living; it is one of those ‘systems we have set up’ and it provides no real stability. A person could be everything, or nothing; what ‘is’ could just be what ‘seems to be’; things that appear unrelated could be the intertwined branches of a single tree, hiding and strangling that tree.

If Ulrich seems on the verge of suffering a breakdown as a consequence of this dislocation from reality, two of the novel’s female characters represent even clearer precedents for Giuliana, because they fall prey to a kind of ‘madness’ that may be a lucid perception of something terrible (or wonderful) in reality. Here is Clarisse (Meingast’s troublesome protégée) trying to co-opt Ulrich into taking his subversion of the reality-cake-moulds a few steps further:

‘Didn’t you once say yourself that the way we live is full of cracks through which we can see the impossible state of affairs underneath, as it were? […] We all want to have our lives in order, but nobody has! I play the piano or paint a picture, but it’s like putting up a screen to hide a hole in the wall. […] [W]e avoid looking at the hole out of habit or laziness, or else we let ourselves be distracted from it by bad things. Well, there’s a simple answer: That’s the hole we have to escape through! And I know how! There are days when I can slip out of myself. […] [O]ne feels connected by the air with everything there is, like a Siamese twin. It’s an incredible, marvelous feeling; everything turns into music and color and rhythm, and I’m no longer the citizen Clarisse, as I was baptized, but perhaps a shining splinter pressing into some immense unfathomable happiness. But you know all about that. That’s what you meant when you said that there’s something impossible about reality, and that one’s experiences should not be turned inward, as something personal and real, but must be turned outward, like a song or a painting, and so on and so forth.’10

Instead of being plagued by ‘possibilities’ or by all the things that could be real (between which no one can make distinctions in the modern world), Clarisse advocates embracing the ‘something impossible in reality,’ the unreality that is an escape from the self and a merging into the universe. Rather than processing one’s experiences inwardly and thereby devising a personal definition of reality, one should externalise those experiences: for Clarisse, playing music or painting a picture is a form of denial, because the music and the picture are displaced from her; instead, just as she is at one with her experiences, so she (and they) will be the song or the painting. ‘Tutti cantavi,’ as Giuliana might say, while the world around her is gradually taken over by paint and music. It is as though Giuliana were fulfilling Clarisse’s wish, but in a way that turns the dream into a nightmare, not an ‘immense unfathomable happiness’ but a condition of boundless terror, not a Siamese-twin-like connection to existence but a deeper-than-ever sense of alienation from those entities one has merged with.

Ulrich’s sister, Agathe, is less given than Clarisse to ecstatic flights of fancy, and more like Giuliana in her ambivalent desire to tap into a seeming unreality that is perhaps a deeper layer of reality:

[Agathe felt] that everything that moved her so strongly was not entirely free of a persistent hint that it was merely illusion. But it was just as true that every illusion contained a reality, however fluid and dissolved: perhaps a reality not yet solidified into earth, she thought; and in one of those wonderful moments when the place where she was standing seemed to melt away, she was able to believe that behind her, in that space into which one could never see, God might be standing. This was too much, and she recoiled from it. An awesome immensity and emptiness suddenly flooded through her, a shoreless radiance darkened her mind and overwhelmed her heart with fear. Her youth, easily prone to such anxieties as come with a lack of experience, whispered to her that she might be in danger of allowing an incipient madness to grow in her; she struggled to back away.11

Agathe is like Karin in Through a Glass Darkly, longing for an encounter with God but recoiling when God emerges from ‘that space into which one could never see’ (see Part 10). The above-quoted passage beautifully captures the insoluble tension in the positions occupied by all these characters: they sense a conflict between truth and illusion, but they live in an age when these things cannot help but be equated with each other; they are conscious of so-called reality’s contingency and constructed-ness, but fearful of the un-structured chaos that opens up in its stead; they reject the norms of sanity and decorum that are imposed on them, but cannot dispel their anxiety at the prospect of ‘incipient madness.’

The refusal to resolve this tension is a powerful gesture in itself. Broch looked ahead, optimistically, to a time of renewal on the other side of disintegration, but Musil (at least in this novel) treats such optimism with irony, as in this dialogue between Ulrich and Agathe:

‘We’re living at a time when morality is either dissolving or in convulsions. But for the sake of a world yet to come, one should keep oneself pure.’

‘Do you really think that will have any effect on whether it comes or not?’ Agathe asked skeptically.

‘No, I’m afraid I don’t think that. Or at most I think like this: If even those people who understand don’t act as they should, it certainly won’t come at all, and there’s no way to stop everything from falling apart!’

‘And what do you care whether it’s any different five hundred years from now or not?’

Ulrich hesitated. ‘I’m doing my duty, don’t you see? Maybe like a soldier.’12

In this and other clashes between men and women in Musil’s novel, we see something of Giuliana’s confrontation with Corrado. Ulrich, in the above passage, lapses back into convention, duty, the tranquil conscience (see Part 21), and a vague sense that we should preserve moral values for some imagined better future. Agathe’s questions and challenges provoke discomfort, hesitation, and ultimately resentment. Giuliana too has questioned Corrado about his career, his philosophy, and the nature of his connections with other people, in a way that makes visible the cracks and fissures in all these things. Not only does Corrado become anxious about his own life, he can also tell that, like The Man Without Qualities, Giuliana’s story will not arrive at a satisfying conclusion. She is not about to resolve her problems, and whatever she is about to do instead, Corrado does not want to see it.

Next: Part 44, Corrado’s exit.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 1195

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), pp. 1312, 1317

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 232

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 61

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 393

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 602

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 670

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 866

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 961

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 1231

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), p. 1367

Very interesting. I will have to see the film, A few thoughts: The idea of succeeding in committing adultery may be inspired by Musil's story, The Completion [or Perfection] of Love, in Unions. Another thing, while you really lucidly describe the despairing moments in Musil's novel, in my reading, there is another aspect you and maybe Antonioni are not appreciating enough: that is, the positive aspect of the possibility sense, of being open. While on the one hand there is a sense of void and meaninglessness, there is also a countervailing freedom and creative force always present, not to mention repeated moments of mystical wholeness and ecstatic higher experience. Everything is (at least) two sided. The inner Ulrich is not only filled with rage at the shallowness of the world's conforming and coercing patterns, but also with love of life and of experiences. Otherwise how would he see that so many people are living in such dull superficiality? He is earnestly searching for something more meaningful--though not ever solid or final, never fully harmonious or complete--a different way of being in the world, more authentically and more alive. It is to be found through art and ethics. My sense from your lovely essay is that Antonioni is more focused on the dark aspects, on the void, than on this other essential part of Musil's quest.