Everything That Happens in Red Desert (42)

Two failed projects

This post contains brief references to abuse and rape.

Corrado has driven Giuliana, not to her home as we might have expected, but to her empty shop on the Via Alighieri. This is a significant location for several reasons. Most obviously, it is the place where these two characters first spoke to each other (after their wordless introduction in Ugo’s factory), so it seems fitting that their relationship should end here. The would-be ceramics shop was also a glimmer of hope for Giuliana, a positive attempt at recovery on her part. These two failed projects – the attempted shop and the attempted relationship – are connected, although only the latter is explicitly referred to in the dialogue of this scene.

We cut from the exterior shot of Corrado’s car, leaving the hotel, to an out-of-focus close-up of a wall in Giuliana’s shop.

The image is divided, slightly unevenly, into two blocks of colour: pink on the left, blue on the right. We were first introduced to the Via Pietro Alighieri by a similarly disorienting (though in-focus) shot of a greenish-grey exterior wall, which became visually legible once the camera pulled back and we saw Corrado getting out of his car (see Part 12).

Here too there is an association with Corrado and his car, subliminally underlining the mirroring of this and the earlier sequence. Now, however, we are introduced to this space in a way that emphasises obscurity and abstraction. Instead of a tangible, real-world structure, we find ourselves looking at two-dimensional colour-blocks. In the previous sequence, and to some extent in the one before that (with the story of the pink beach), amorphous colour-shapes and objects (especially pink and blue ones) have been used to represent the turmoil in Giuliana’s mind and the menacing forces in the world around her. The sudden and inexplicable, though momentary, take-over of the film-image by this pink-and-blue haze creates a frisson of anxiety, like a hangover from the nightmare we just experienced in Corrado’s hotel room.

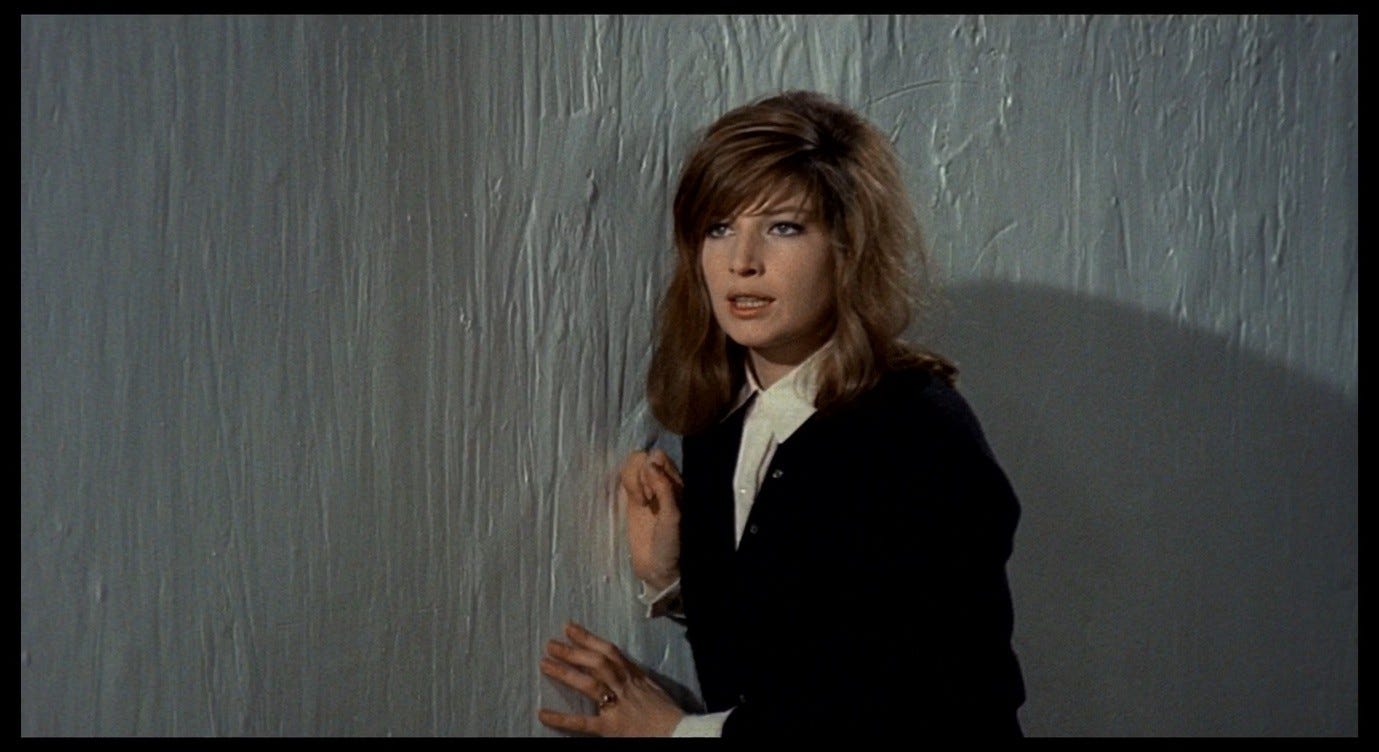

As Giuliana’s red hair enters the shot from the left, and the camera pans right to follow her, we realise where we are. These are the walls of her shop.

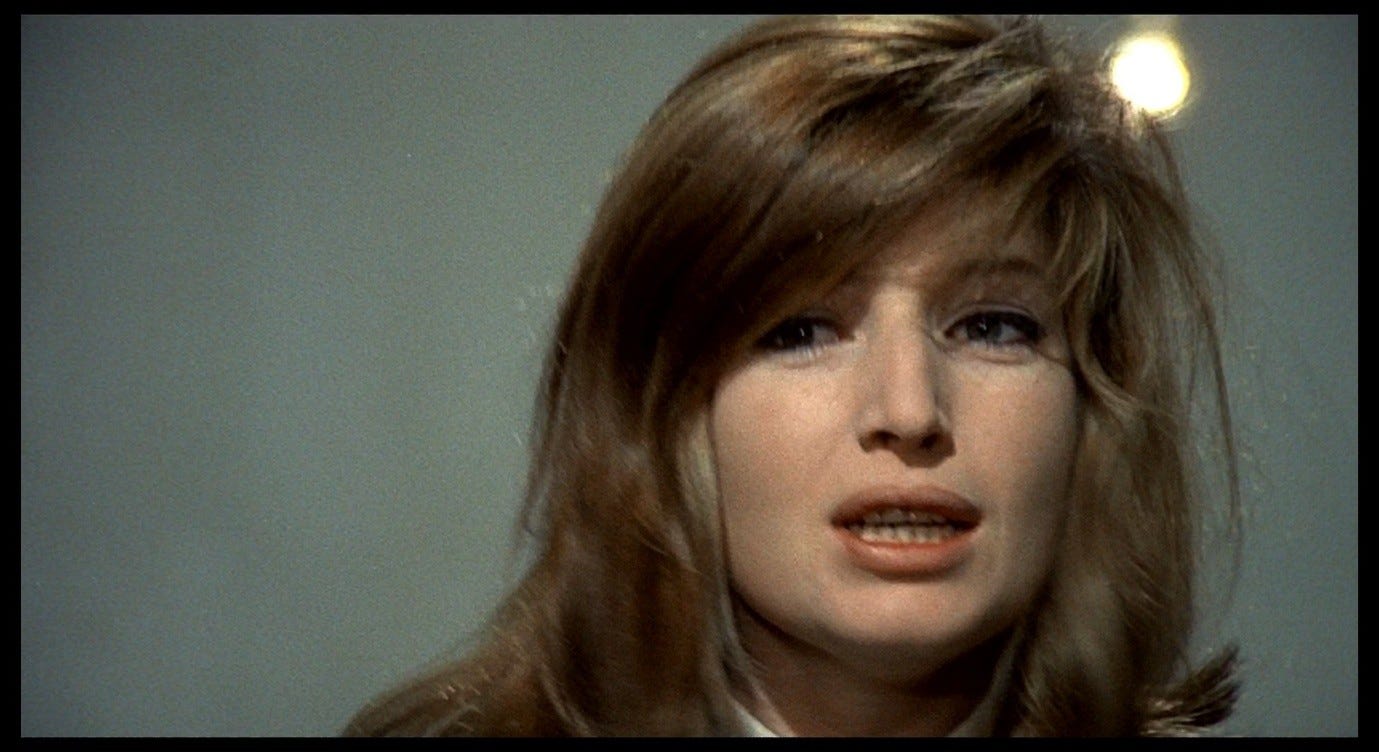

As the image comes into focus, we see Giuliana turn to look at the walls and ceiling as she did when Corrado first visited.

Those 2-D blocks are the daubs of paint she applied to the walls in her attempt to find the right colour-scheme. She had proposed celeste e verde (light blue and green) on the basis that they were cool colours and would not disturb the objects being sold. The pink we have just seen on the left of the screen may remind us of the pink-coated hotel room, in which everything became the same colour as the ‘objects on display’ – the pink bodies of Corrado and Giuliana – and the effect was both highly neutralising (the bodies seemed sedated, inert) and highly disturbing (everything looked like human flesh). Now, as the camera pans away from the pink-blue haze, we see Giuliana standing against a white background, and much of this scene will play out within this white void. In its near-emptiness, it is even more of a void than the reception of the hotel, which was at least strewn with (white) objects. Here, there are just bare walls whose uneven surfaces recall the once-liquid state of the plaster and paint, their waves and streaks now solidified but still visually suggestive of movement. The colour and texture of this space – as well as its emptiness, illuminated by the bare light-bulb dangling overhead – denote its ‘unfinished’ status. It is a place that never quite comes into being, just as Giuliana’s relationship with Corrado never quite becomes substantial. Giuliana looks at these surroundings with a wry, ironic half-smile, contemplating the absurdity of her failed enterprise.

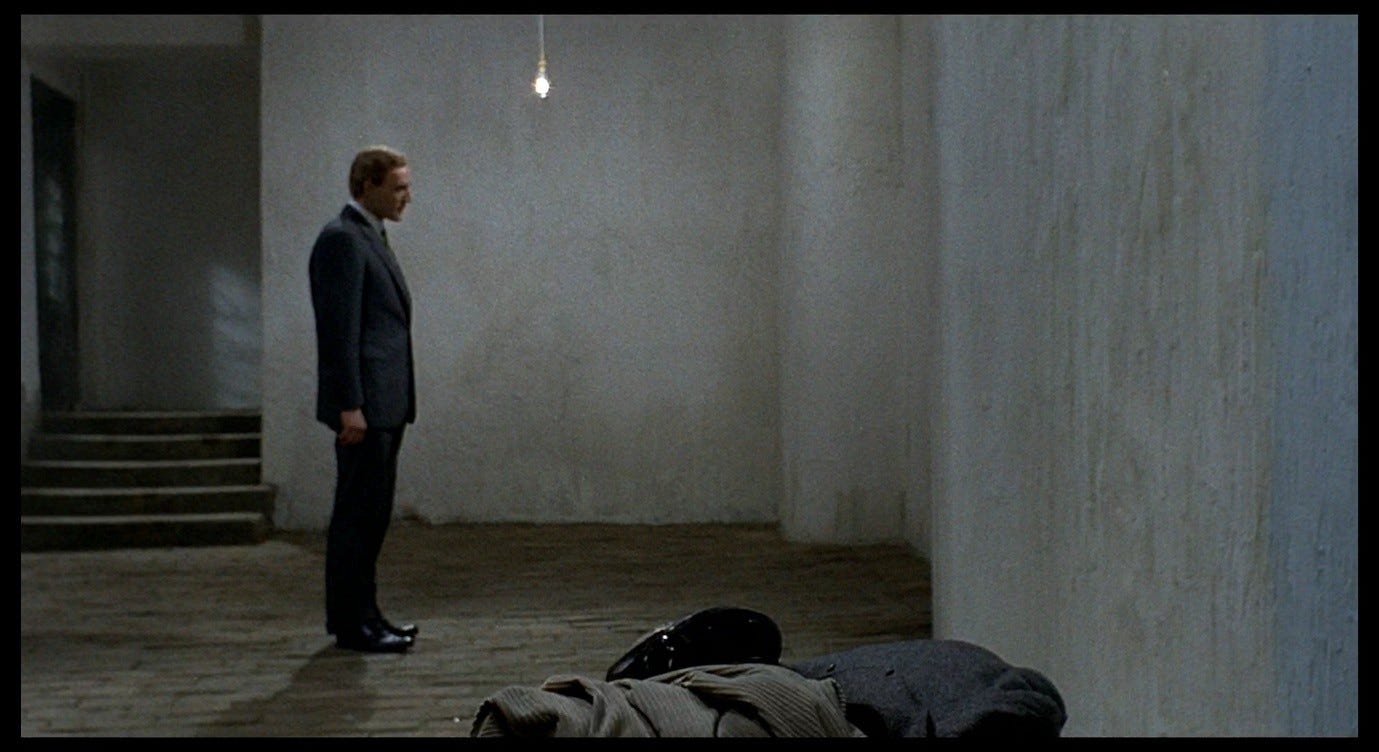

‘Giuliana,’ Corrado says, in the condescending tone of an adult trying to get a child to pay attention. We see him from the side, in a wide shot that takes in most of the room but conspicuously excludes Giuliana, who is hidden in an alcove to the right.

As in earlier scenes, the continuity between one shot and another is dubious. We cannot now see the window Giuliana walked past a moment ago, which I think is on the other side of the room. Like the hotel, this is a place where internal states might shape external reality, where Giuliana might change position instantly based on the psychological or emotional configuration between her and Corrado. The composition here looks like a ‘farewell’ image, an act of separation rendered visually. Corrado appears to be saying a final goodbye to a person who is already absent, and we anticipate that he will soon collect his coat from the stool in the foreground, then turn around and exit through the door we see on the left.

First, though, he changes position in a deliberate and choreographed way, stepping from one side of the light-bulb (which illuminates his face) to the other, so that it now illuminates the back of his head, leaving his face in shadow from Giuliana’s perspective.

As he steps forward, he addresses Giuliana in a demanding tone: ‘Tell me what your intentions are. What do you want to do?’ From her hiding place, Giuliana repeats the significant trigger-word from the previous scene, ‘Niente.’ ‘But that’s absurd!’ exclaims Corrado, barely moving a muscle. The source of the condescension in his tone is, ostensibly, his concern for her. She ought to be doing something to help herself, to recover from her illness. She ought to have some plan, some intention (such as pursuing a relationship with him, perhaps?). To have none – to intend ‘nothing’ – is absurdly irresponsible. Corrado evidently sees his rape of Giuliana as an attempt to help her, and her subsequent rejection of him as a refusal of help. So, he passive-aggressively asks, what is her recovery plan?

Though he moves closer to Giuliana, Corrado becomes literally more obscure, his face darkening as it moves past the light-bulb. His words and his tone indicate the widening distance between them. He seems cold, unsympathetic, uninterested in hearing or understanding her point of view. This is not only in contrast with the ostensible warmth and intimacy of his behaviour in the hotel room, it shows up how false that warmth and intimacy were. Corrado’s final scene shows him as he ‘really is,’ with all the seductive geniality stripped away. Like Piero in L’eclisse or the photographer in Blow-Up, he seems chillingly empty and cold when pared down to his self-alone, as if he were (like Giuliana’s shop, like their relationship) not quite there, not quite real.

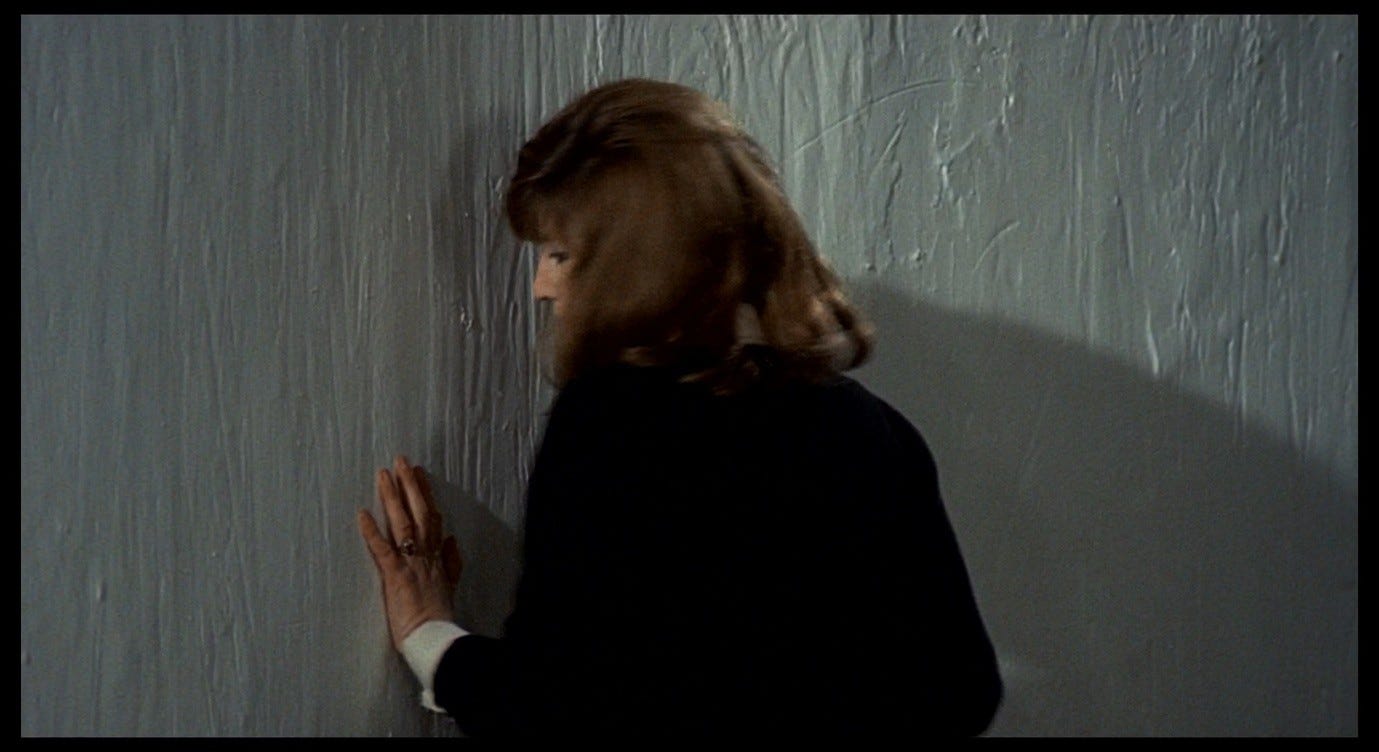

His robotic stillness is, as usual, contrasted with Giuliana’s agitation. She gingerly emerges from her alcove and walks across the room towards us, muttering that it is useless for Corrado to worry about her.

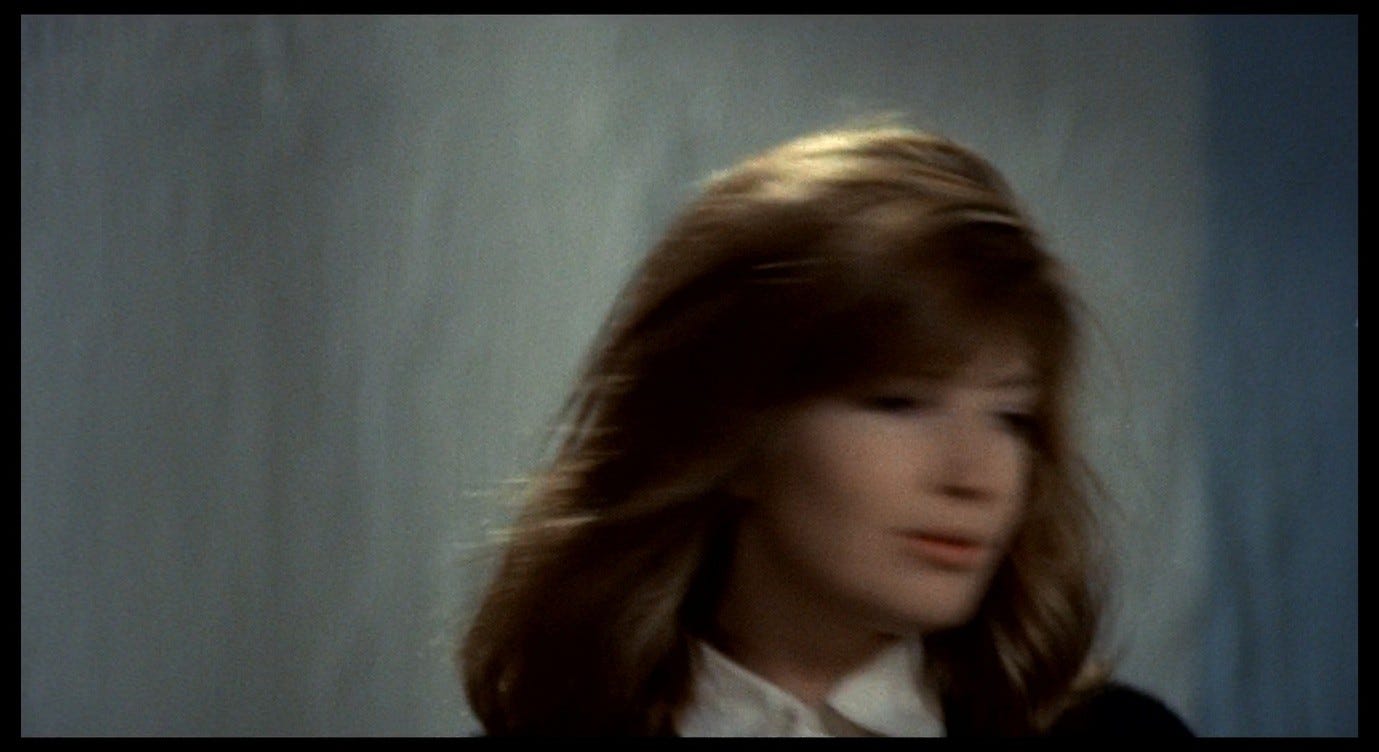

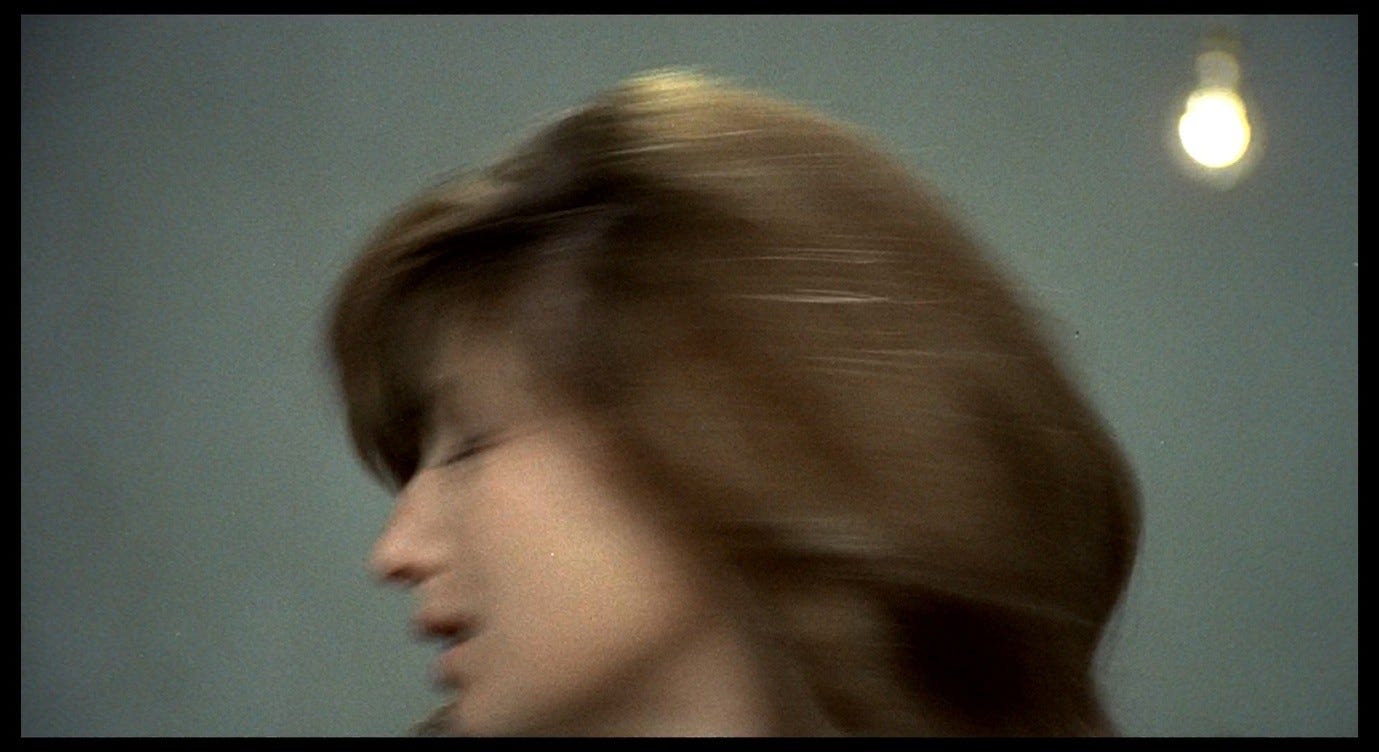

After this static wide shot, there are two mobile long-lens shots that follow Giuliana’s increasingly panicked back-and-forth pacing across this empty room. We cut on Giuliana’s turns: first when she turns from her alcove towards the bare wall.

Then when she has approached the camera again and suddenly turned back.

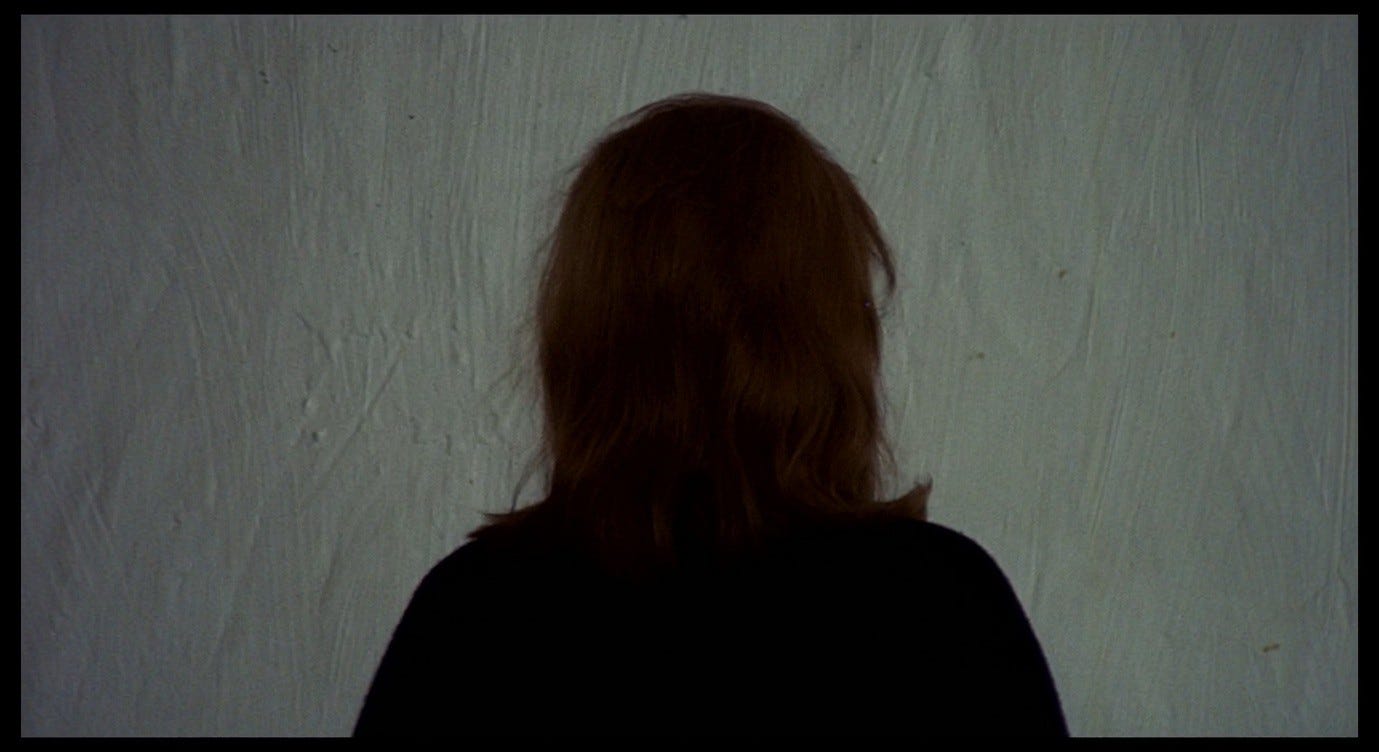

After she has once again approached the camera (which dollies backwards, tracking her movements as she zig-zags across the room) and whipped around to face Corrado, we hold for a moment on the back of her head, and she becomes still.

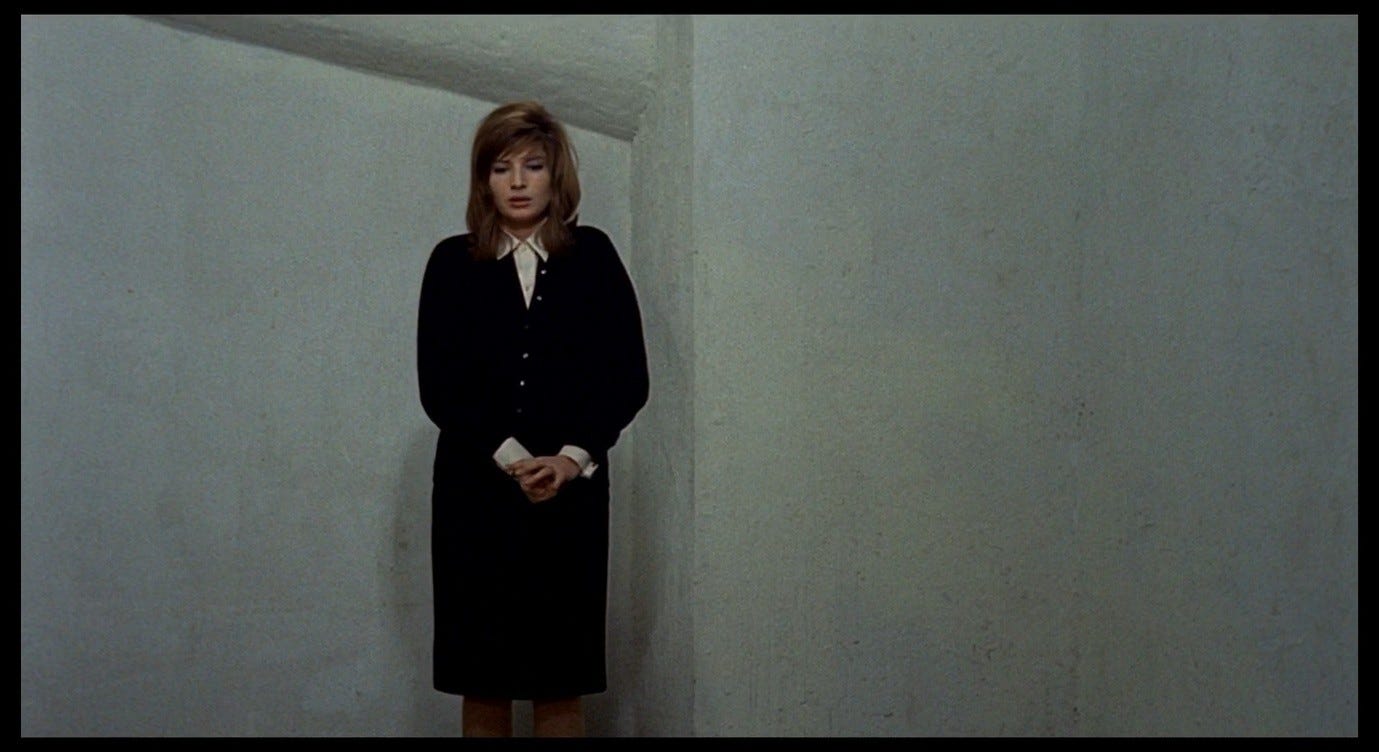

After this moment of stillness, we cut to a wide-shot of Giuliana standing against a bare wall, the same one she stood against earlier in the film when she asked Corrado what products she ought to sell (see Part 15).

She asked that question in an attempt to connect, to establish a dialogue between herself and this other person. Now, she has given up on any such attempts.

During those frenetic travelling shots, when we follow Giuliana’s movements in claustrophobic close-ups, she explains why there is no point in Corrado worrying about her:

For months, everyone has done nothing else. I go to the doctors and they talk to me about me [mi parlano di me]. And instead it’s when I am alone that I am unwell [è quando resto sola che sto male]. I can’t take it anymore [Io non ne posso piú]!

She paces back and forth and the camera picks her up again and again at each turn, like the solicitous people in her life who observe and analyse her, to whom she turns for help but from whom she is also desperate to escape. The way in which the film repeatedly captures her image and then edits these images together – blurs them together, too, in the loss of focus sometimes caused by the rapid camera movements – is like the process of ‘talking to her about her,’ creating a narrative from (and imposing a narrative upon) these recorded observations of Giuliana. Bookending the frenetic paparazzi-shots are the static wide shots in which she seems trapped in a different way: pinned against one wall by Corrado; pinned against another wall by the camera.

The problem, she insists, comes when she is alone, or when she stays alone (quando resto sola). Sola can mean alone, single, or lonely, and the phrase da sola means ‘by oneself,’ as in ‘I cannot manage by myself.’ Part of Giuliana’s meaning refers to a contrast between the impositions of others and her own autonomy. She is not saying that she needs constant companionship. We have seen that being with other people – husband, son, friends, lover, etc. – is often deeply problematic for Giuliana. The wish she expressed in the hotel room, of having her loved ones around her like a wall, represented a desire to feel protected and supported enough that she could function well da sola, not a desire to spend all her time with those loved ones. What she gets instead is a kind of parody of that wish, in which others form an inescapable wall that is constantly holding up a mirror to show her who and what she is, how she ought to behave. Giuliana lives in an environment of constant sensory overload and constant surveillance, where she can never be alone or at peace, and where everything around her is imposing specific categories and functions on her.

A key part of the problem here is that these voices that ‘talk to Giuliana about Giuliana’ are not really engaging with her at all. The clue, as in the conjuring of her doppelganger in Mario’s apartment (see Part 17), is in the doubling effect of the phrase mi parlano di me. The doctors create a second Giuliana and talk about her, and demand that Giuliana talk to her as well – she has to explain to this second Giuliana who she is. This has an annihilating effect on Giuliana herself, Giuliana da sola. The uncanny post-coital Giuliana, lying quietly in bed with Corrado at the end of the hotel room sequence, was at odds with the Giuliana we saw a moment later, running out into the street. Corrado, in dismissing her wishes and feelings, effectively caused a second Giuliana to come into being.

This doubling could be likened to traumatic dissociation, and I think Giuliana is invoking this concept when she describes feeling isolated in her illness while everyone around her talks (to her) about her. Her final outburst, ‘Io non ne posso piú!’, explains her previous answer of ‘Niente’ to Corrado. Deprived of any sense of self or autonomy, she feels incapable in a directionless, all-encompassing manner, and upon declaring this she suddenly falls still and silent.

This act, of falling silent in front of an expansive blank wall, calls to mind the existential and artistic crisis at the centre of La noia (Boredom), Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel. La noia’s protagonist, Dino, describes his boredom as

a malady affecting external objects and consisting of a withering process; an almost instantaneous loss of vitality – just as though one saw a flower change in a few seconds from a bud to decay and dust. The feeling of boredom originates for me in a sense of the absurdity of a reality which is insufficient, or anyhow unable, to convince me of its own effective existence. […] Boredom, for me, was like a kind of fog in which my thought was constantly losing its way […] like a person in a thick mist who catches a glimpse now of the corner of a house, now of the figure of a passer-by, now of some other object, but only for an instant, before they vanish.1

The boredom that manifests as an alienation from reality (Alienation was the novel’s working title) also alienates Dino from his work as an artist: ‘I am no longer a painter because I have nothing to paint,’ he says, ‘that is, I have no relationship with anything real.’2 The novel begins with Dino slashing one canvas to ribbons and then replacing it with a blank one. Somehow, these two gestures become a lucid expression of his alienated state of mind:

I had been working on that canvas for the last two months, doggedly and without pause; slashing it to ribbons with a knife was equivalent, fundamentally, to finishing it – in a negative manner, perhaps, as regards external results, which in any case had little interest for me, but positively, in relation to my own inspiration. In fact my destruction of the canvas meant that I had reached the conclusion of a long discourse which I had been holding with myself for an interminable time. It meant that I had at last planted my foot on solid ground. And so the empty canvas that now stood on the easel was not just an ordinary canvas which had not yet been used; it was a particular canvas that I had placed on the easel at the termination of a long job of work.3

I wonder if Antonioni was thinking of these gestures when he filmed the farewell scene in Giuliana’s shop. In a publicity still, which may represent an un-filmed alternate version of this scene, we see Giuliana standing in her shop, facing both Ugo and Corrado, framed by the paint-streaks she has splashed over the walls.4

The opened, dribbling cans of Tintal paint in the lower-right corner suggest that the paint-streaks must have been multi-coloured, but in black-and-white they are somehow suggestive (at least to my diseased eyes) of blood. In La noia, Dino later repeats his canvas-slashing gesture in a nightmare, in which the canvas turns out to be the body of a female model who is ‘now bleeding from a large number of thin, vertical wounds,’ and whose body is eventually ‘covered with a network of blood.’5 Thomas Peterson suggests that Moravia was inspired by the futurist painter Lucio Fontana, who sliced his canvases with a razor, ‘replacing the image as something rendered or depicted with a sculptural and optical event.’6 As we saw in Part 11, Fontana was inspired by Red Desert to paint a blood-red canvas and then slash it, as though to suggest a body that was all blood on the outside and all shadows on the inside.

The year after Red Desert, in Il provino, Antonioni showed Princess Soraya trying out different wigs and different personae in front of a mirror, before splashing black paint over it and over her own image, with a look of defiance.

These creative acts have several important things in common. They all express a sense of alienation from an absurd reality: that face in the mirror, that image to be depicted on the canvas, those walls to be decorated; these things do not really exist, and their non-existence, their absurdity, prompts a violent act, an event. Tearing the canvas, splashing the black paint, and then replacing the defaced surface with a completely empty one, are all confrontational gestures. In that publicity still from the lost scene of Red Desert, Giuliana looks half-apologetic, half-defiant as she faces Ugo and Corrado. It is as though they have caught her vandalising her own shop, and now she has to justify this act to them.

The change from this version of the scene to the blank-walled one is like Dino’s shift from slashing the canvas to enshrining an empty one. Even vandalism would be too much of an engagement with reality; the perfectly clean white surface is, in a way, a more subversive and despairing gesture.

La noia’s relationship with Red Desert becomes more complicated when we look at the similarities between Dino and Corrado. The plot of Moravia’s novel centres upon the 35-year-old Dino’s affair with a 17-year-old girl, Cecilia. (Moravia himself was about to leave his wife for a woman 29 years his junior.) Dino becomes obsessed with Cecilia because she is, in some way, inextricably linked to his all-consuming noia:

I reflected that the canvas was blank because I did not succeed in getting possession of any kind of reality, in the same way that my own mind was blank when confronted with a Cecilia who eluded me and whom I could not succeed in possessing. […] I felt that there was a link between the crisis in my painting and my relationship with Cecilia; between my inability to paint on the canvas that stood on the easel and my inability to possess Cecilia upon the cushions of the divan […] It was an obscure, sinister link; there is a similar significance, for a traveler lost in the middle of a desert, in the white bones scattered on the sand.7

The problem revolves around possession and mastery: a man possesses a woman, Dino thinks, by having sex with her, just as an artist possesses some aspect of reality by depicting it. He is abusive and coercive in his treatment of Cecilia, who remains (as Moravia paints her, or as Dino perceives her) largely impassive and serene. She is another component of that absurd, elusive reality that Dino can no longer engage with, and he reads this – like a man interpreting bones in a desert – as a forecast of his own annihilation. At one point, Dino asks Cecilia what she thinks about him, and she says:

‘Nothing.’ ‘But just now you said you thought lots of things.’ ‘Yes, I said so, but I see I was wrong.’ ‘But don’t you find it tiresome to think nothing, absolutely nothing, about the man you make love with?’8

I think there is a clue, here, to the source of Corrado’s strangely disgruntled tone in the farewell scene. When he asks Giuliana what she intends to do and she says ‘Nothing,’ he angrily protests that this is absurd – but why is it absurd? What exactly does he expect her to say, or what plans does he expect her to have formulated? Antonioni saw Corrado as a confused character, looking for a way to ‘solve the problem of his life’ through various actions but failing to realise that ‘this problem is inside himself, not outside.’9 He has ‘almost got to the point of neurosis,’10 so that for him, Giuliana serves as a harbinger of his own imminent breakdown. His spaced-out disengagement during the briefing sequence is like Dino’s sense of being infinitely distanced from his surroundings in his studio:

When I entered the studio and sat down in the armchair in front of the empty canvas which still glimmered white upon the easel, I said to myself: ‘I am here and they are there.’ By ‘they’ I meant the objects around me – the canvas on the easel, the round table in the middle, the screen in the corner to the left behind which the bed was concealed, the terra cotta stove with its pipe going up into the ceiling, the chairs with notebooks lying on them, the bookshelf and the books. They were there and I was here, and between them and me there was nothing, truly nothing, just as, perhaps, in the interstellar spaces, there is nothing between the stars, millions of light-years distant from each other.11

Like Corrado, Dino is in the midst of a professional crisis which is then exacerbated by a personal one, and together these crises place him in a vast desert, or in the vacuum of space. Tellingly, when he first encounters Cecilia, he experiences a kind of nausea:

the same feeling of nausea that probably everyone experiences when on the threshold of some unknown, vague reality; or perhaps, more simply, of reality unadulterated, if one has become accustomed, over a long period, to not facing it.12

She becomes, in other words, a personification of the noia that afflicts him, an almost allegorical figure:

It was as though she had been born with the detachment from external things which to me seemed an intolerable change from a very different original state; as though what to me seemed a sort of sickness was, in her, a sane and normal fact.13

In one obvious sense, this is a reversal of the relationship at the centre of Red Desert: Giuliana is anything but sanguine about her detachment from her surroundings, while Corrado seems to regard himself as a relatively sane, normal person. But the similarities operate on a deeper level. Dino is frustrated with Cecilia for being so stubbornly, pathologically afflicted with (or symbolic of) the illness to which he is now succumbing. More specifically, he is frustrated with Cecilia for implicitly suggesting that this illness is not constituted by a lack of connection with reality, but by a lucid perception of ‘reality unadulterated,’ with a reality defined by alienation. It is that same kind of reality Antonioni saw as being hidden beneath infinite layers of images, and therefore unattainable. Encountering Cecilia, Dino sees himself where he truly is – in the bone-strewn desert – and his aggressive, abusive, resentful attitude is symptomatic of his unwillingness to acknowledge this desert. He is a strange mixture of Giuliana and Corrado: insistent and defiant when it comes to his boredom and his empty canvas, but deeply and violently in denial about the malattia dei sentimenti that haunts his current relationship.

Next: Part 43, Something terrible in reality.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), pp. 3, 63

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), p. 90

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), pp. 3-4

‘Scena del film “Il deserto rosso”’, from the photography archive on the Regione Lombardia website

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), p. 69

Peterson, Thomas E., Alberto Moravia (New York: Twayne, 1996), p. 91

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), pp. 220, 256

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), p. 210

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 291. In the French text, Antonioni says that Corrado is trying to resolve ‘le problème de sa vie.’ Taylor translates this as ‘his existential crisis,’ but I have opted for a more literal translation here. French text from Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘La nuit, l’éclipse, l’aurore’, in Cahiers du Cinéma 160 (November 1964), pp. 8-17; p. 15.

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; p. 284

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), p. 130

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), p. 63

Moravia, Alberto, Boredom (1960), trans. Angus Davidson (New York: The New York Review of Books, 1999), p. 102