Everything That Happens in Red Desert (36)

The journey to the hotel

As Giuliana runs away from her son and from her home, the telephoto lens collapses the different layers of the domestic space into each other, making her escape seem logistically impossible. Somehow she reaches the staircase – the one she could not descend in the night-terrors sequence – but as she disappears from our view, the camera pans right and comes to rest on an out-of-focus image of the purple/yellow chalk-drawing on Valerio’s blackboard.

It is as if she has walked, not out of the house, but into the chalk-drawing. We cut to a similarly out-of-focus image of the docks outside.

The disturbing electronic hum on the soundtrack transitions (a split-second after the cut) to a slightly different electronic hum. The internal and external spaces are differentiated but literally seem to blur into each other: escaping from one into the other is no escape at all. Just as the fantasy cove turns out to be little more than a variation on the ‘real’ world Giuliana lives in, so her home is a variation on the industrial hellscape outside. The interiors of the house are conflated with each other, the domestic space is conflated with the harbour, and now Giuliana will flee to a different interior space – Corrado’s hotel room – where she will again find reality collapsing in on itself. This interlude, which traces Giuliana’s journey from home to hotel room, will use various means to reiterate the idea that this is not really a journey at all, but an ongoing condition of malevolent entrapment.

The blurry image that succeeds that of the chalk-drawing is quickly disrupted by Giuliana running into the frame.

The camera pans right to follow her, and she shifts in and out of focus as we become more oriented in this space, realising (for instance) that the blurry shape at the start of the shot was a boat in the harbour.

By the time the panning movement concludes, we have a clear, crisp view of a large ship in the distance, on whose deck stands a man, looking eerily in Giuliana’s direction. He is completely still, as though watching her or even waiting for her.

As in Giuliana’s free-associating fantasy of the pink beach, there is a kind of associative connection between the figures and places she moves from and to in this sequence: the stranger stands on the deck of the Tulipa, watching, and Corrado too will be a somewhat inscrutable scrutatore, standing waiting for her at the end of the hotel corridor, observing her with an eye that may or may not be benevolent. Like the man on the ship, Corrado is forever travelling, forever on the point of being swept away by the currents of industry. In her bedtime story to Valerio, Giuliana has fantasised about living by the sea, escaping from people, feeling drawn to a passing ship – but that story also grappled with the impossibility of escape, and with the inevitable disillusionment when the ship turns out to be vacant and sails away. This pattern will be repeated in Corrado’s hotel room.

The second exterior shot also begins with a disorienting image and only gradually tells us what we are looking at. We see a dark grey surface and some railings, then the camera zooms out (again beginning to move as Giuliana enters the frame) to reveal that this grey surface is a wall dividing a dirt-path from a complex of spherical edifices, all identical, each with a yellow stairway coiled around it.

Our old friend, the spouting flare-stack, is briefly visible in the far distance, though its distinctive song is not audible above the deafening noise created by the rest of the complex, and it is quickly excluded visually as well as aurally when the camera pans right. We have come a long way since that opening scene: now the factory buildings seem cosmically vast, like constellations of planets that cannot be perceived all at once by the human eye, only by an elevated, godlike camera. From a starting position at Giuliana’s level, with the frame matching her height, the camera’s zoom mechanism has shrunk her until she is confined to one diminutive layer of the image, totally overshadowed by the industrial orbs. We may just about notice the thin strand of green grass at the base of the wall, like a single remaining thread of the natural world along which Giuliana is precariously walking.

The effect of this image is similar to that of the piled blue demijohns at the end of the briefing sequence (see Part 29).

That shot expressed something about Corrado’s life and environment; this one expresses something about Giuliana’s. She lives, not among these things, but beneath them. She is not even ‘watched over’ by these grey, eye-like orbs. They exist on a higher plane, oblivious to her, gazing coolly up at the universe. She appears both shut out of and trapped within this world, incidental (and inessential) to its continued operation, yet incapable of freeing herself from it. The image of her walking along this path evokes devastation and loneliness, but also resignation. Giuliana is about to tell Corrado that her condition seems incurable, and this zoom-out image of her walking alongside the grey wall is a very beautiful expression of this feeling in visual terms, before it is verbalised.

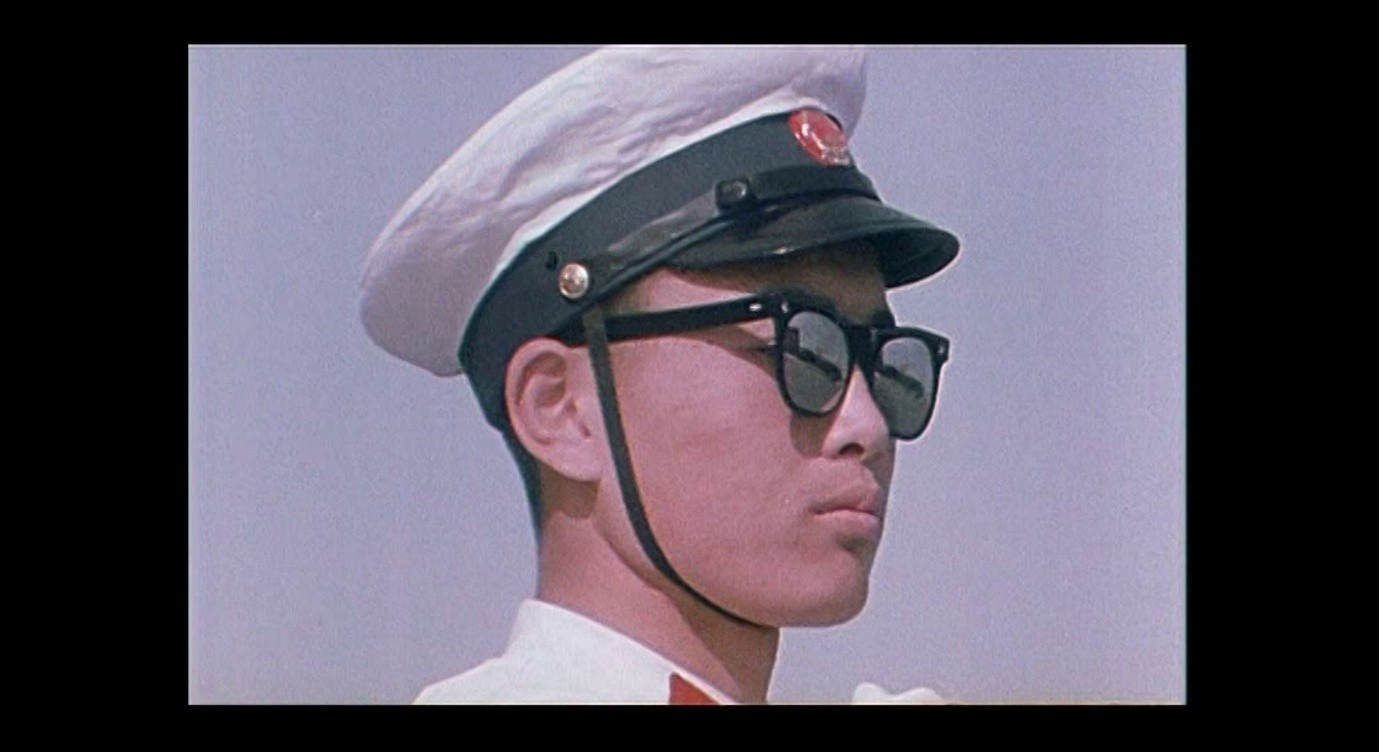

Beginning close to the wall and then zooming out to reveal something of its scale – though not its full scale, since it extends indefinitely beyond the left and right edges of the frame – underlines the enormity and monotony of Giuliana’s environment. To reach her goal, to walk along the full length of this wall, seems less and less feasible as the zoom continues. This, the image tells us, is what Giuliana is up against. Antonioni uses the zoom in similar ways in Chung Kuo: Cina, for example when he begins with a close-up of a traffic officer whose sunglasses reflect the city around him, then zooms out to locate him in the context of a busy intersection near the Forbidden City.

Later, there is a shot of a woman sitting in a window, watching the camera. She is already seen from a distance, marginalised at the far right of the frame, but as we zoom out to reveal the frames-within-frames that surround her, she fades into relative darkness and we can barely see her face anymore.

In making this documentary about China, Antonioni seems constantly preoccupied with the place of the individual within overwhelming structures, but also with questions (implicit in shots like these) about how the camera relates to both individual and structure. The traffic officer’s sunglasses prevent us from looking into his eyes, instead presenting us with a reflection of the larger world around him – in fact, with a view not unlike the one we will get once the camera has zoomed out, of the other side of the intersection. Perhaps this man does not want to be looked at, in this moment, as an individual with feelings, but rather in terms of his role and function as a facilitator of Beijing’s circulating traffic. The woman in the window disappears into the shadows, but was she any more ‘visible’ when we saw her up close? Does the zoom-out, by making her small and obscure, in some way constitute an interpretation of what her look says to us: ‘Step away, do not look at me, leave me alone in the dark’?

Wim Wenders, early in the making of Beyond the Clouds, objected to Antonioni’s use of two cameras to film a scene from different angles, and (for similar reasons) to his use of the zoom lens:

Unquestionably, it’s a technique that makes for greater distance from the characters: the narrator’s point of view isn’t that of the actors. It’s purely Michelangelo’s point of view; he’s standing alongside the characters, not identifying with them at all. […] [W]hat I’ve always done in my films is empathize with my characters. Michelangelo’s point of view is considerably cooler, which isn’t to say that it’s necessarily ‘dispassionate.’ What his cameras show doesn’t tally with any one individual’s eye, but represents an ‘objective view.’ And that’s also the only way I have of justifying to myself Michelangelo’s liberal use of the zoom lens. That piece of equipment really is my bête noire, because it doesn’t correspond to the vision of a human eye; it’s an artificial vision. Human beings need to go up to something to see it closely, and the way you do that with a camera is to move it up. You can’t make a thing ‘zoom’ into close-up just with your eye.1

However, the zoom-out of Giuliana in Red Desert is a good illustration of how this distancing effect can simultaneously prompt empathy. Not only is the eventual wide shot expressive of her feeling of being dwarfed by the industrial landscape, but the zoom-out itself suggests something of that ‘step away’ feeling communicated by the similar shots in Chung Kuo: Cina. To understand what is about to happen in Corrado’s hotel room, it is vital that we grasp this counterintuitive aspect of Giuliana’s emotional state. At this point in the story, in an obvious sense, she is looking for connection, but less obviously – and perhaps more importantly – she is trying to push something away from her, to create a space between it and herself. We would not know that she felt this way if the camera were ‘empathising’ with her by looking at her in a more human-like manner. The human eye is limited, when it comes to seeing other people, in ways that the camera eye is not. The two-camera technique referred to by Wenders (and not showcased in this particular sequence) may also be in service of something more than an ‘objective’ view. It may instead represent two subjective views, or a single subjective view defined by conflict and ambivalence.

The foyer of Corrado’s hotel has a vacant feel, primarily due to its almost universal whiteness. The walls, floors, ashtrays, and even the fake plants are painted white.

The greyness of the Via Alighieri was suggestive of age, decay, and neglect, but the interior of this hotel appears brand new. Like the white hospital at the start of La notte, or Giuliana’s own white-walled apartment, this foyer is clean and clinical, but also de-humanising. People appear stark and lonely against a background like this, isolated from the world around them. It is a space devoid of colour, literally blank, as though the decorators had forgotten to paint it. This reinforces the impression of a temporary space, a place-holder home where Corrado lives until it is time to move on.

It also makes the foyer seem a little unreal, like an incomplete corner of reality. In Pabst’s Secrets of a Soul, we see the protagonist’s waking experiences reproduced, when he describes them to a psychoanalyst, against stark white backgrounds and from different angles.

These are images from the life of the mind, registering the aspects of experience that have an emotional impact and excluding all the other details that a camera would automatically pick up. Not only that, but the mind heightens and distorts these emotional experiences, causing the man to remember the affectionate smiles of his colleagues as cruel, mocking laughter.

There is something of this in the white hotel foyer in Red Desert. Although we are not inhabiting Giuliana’s memory, we will from now on be increasingly conscious of seeing things as she feels them, not necessarily as they ‘are’ in a literal sense. Objects, colours, and sounds may be isolated, accentuated, and even distorted while we inhabit her point of view. Arguably, this frames Giuliana as a neurotic woman beset by misguided fears of the world around her, whom we are invited to view critically and at a distance; as in, ‘The foyer can’t possibly be this white, she’s just going crazy, she should go back to the clinic.’ This is not how I respond to the film – rather, I recognise the feeling of reality going blank around me, and find it vividly captured here – but it is important to acknowledge that we are not forced to empathise with Giuliana, that we can see her from another point of view (the second camera, so to speak), and that we may judge her to be as sick and in need of psychiatric care as the hero of Pabst’s film. Nuanced combinations of these two attitudes are, of course, also available to us.

Giuliana’s entry into this space is characteristically impulsive and spasmodic.

There is an obvious contrast between the way the concierge steps calmly into the frame and looks up at his customer, and the way in which Giuliana dashes into the frame as though she arrived late on set and is trying to hit her mark.

She just about reaches the correct spot in time to meet the camera’s gaze, as it pans left. However, she then seems to have forgotten her lines, staring in blind panic at her fellow actor for a moment.

No sooner has she managed to deliver her first line – ‘Which room does he have?’ – than the conversation is derailed by the concierge’s apologetic question, ‘Sorry, madame...who?’ Giuliana is both desperate to reach her destination and unsure of what (or who) this destination is. There is something arbitrary about her coming here, and a sense that Corrado’s individual identity may not matter.

From another perspective, we might argue that Giuliana’s motivation is quite clear. Her son’s inhuman, robotic behaviour drives her to seek out a flesh-and-blood human being, any human being; her lack of connection with Valerio, even in the moment of embracing him, drives her to seek out a connection, any connection. Again, the anonymity of the man on the Tulipa foreshadows the any-port-in-a-storm mindset of this visit to Corrado’s hotel, and of Giuliana’s subsequent encounter with the unnamed Turkish sailor.

The concierge’s question, ‘Don’t you remember the name [il nome]?’, triggers an extraordinary series of gestures from Giuliana. She looks around at different points in the space as she tries to access the desired name.

Echoing her earlier questions about what she should look at, how she should look, or what she should do with her eyes, she seems to be trying to find the right eye-movements to get her mind to function properly, to make the gears mesh. She thrashes her head from side to side, shaking her hair about, and at one point she runs her hand down the right side of her face, moving it through the curve of her hair towards her mouth.

Giuliana tries to bring not only her eyes, but her head, her hair, and her mouth into some kind of alignment so that she can respond coherently. Once again, she displays that everything-at-once tendency the doctors tried to cure: rather than accessing the name in her mind, then expressing it with her mouth, she responds with mind-head-eyes-hair-mouth in a way that makes her seem on the verge of disintegration.

As she repeats the phrase, il nome, she also deconstructs the two words into their component parts, each of which is in turn distorted into a different word. The word il comes to sound like io, then she fixates on the no of nome, and even the vowel sound at the end of nome becomes obscure enough that it could be mi or me. The concept of a name, an identity – the thing that represents who this person is – transforms into a negation: ‘the, I, no, not, me.’ Giuliana’s head shakes rapidly, suggesting both a continued attempt to shake herself into order, to snap out of it, and a desire for self-destruction, for self-negation.

The shot focuses entirely on Giuliana, with the concierge a deathly-still blur on the right-hand side of the frame. When we finally cut to her point of view, we see the back of her head – her wave of red hair – in focus in the foreground, while the concierge seems to dissolve into his blank surroundings in the background.

As Giuliana runs upstairs, we hear the concierge trying to call her back, but we still do not see his face. His hand enters and then leaves the frame as he picks up the phone to warn Corrado about this unexpected visitor.

The film wilfully resists giving us any sense of an interaction between these two characters. The scene is about Giuliana and the concierge is a barely-present amorphous shape on the fringe of her reality.

Once again we might think of the standard adultery drama, in which this encounter with an insinuating desk-clerk would prompt shame and embarrassment in the protagonist, making her hesitate to name her lover. But this desk-clerk is not insinuating, indeed we hardly get any sense of his response to Giuliana. At most he seems mildly perplexed by her inability to communicate, then mildly agitated when she runs upstairs. Our protagonist’s embarrassment has nothing to do with the illicit affair (which I do not think she is actively pursuing), but with a more fundamental violation of social structures, namely those concerned with the coherence of people’s discrete identities. When she spits out the word ‘Corrado’, she feels an evident relief at having found the name, but equally evident pain at having had to wrench it out, at having had to name and individualise Corrado. She is humiliated by her own seeming incompetence and also somehow indignant at the concierge’s unreasonable demand. Why does he need the name? Why does the name matter?

If individuals – Giuliana, Corrado, the concierge – seem to be disintegrating, so too does the world around them. Above, I suggested that the hotel foyer looks unfinished, as though the decorators forgot to add colour. But it also looks drained of colour. This space is the flip-side of the blackened ground and vegetation outside the factories.

Now we see a blanched interior space where all colour and ornamentation have been burnt away, leaving only the ‘functional’ in place. From Giuliana’s perspective, this space seems pared down almost to the point of non-existence.

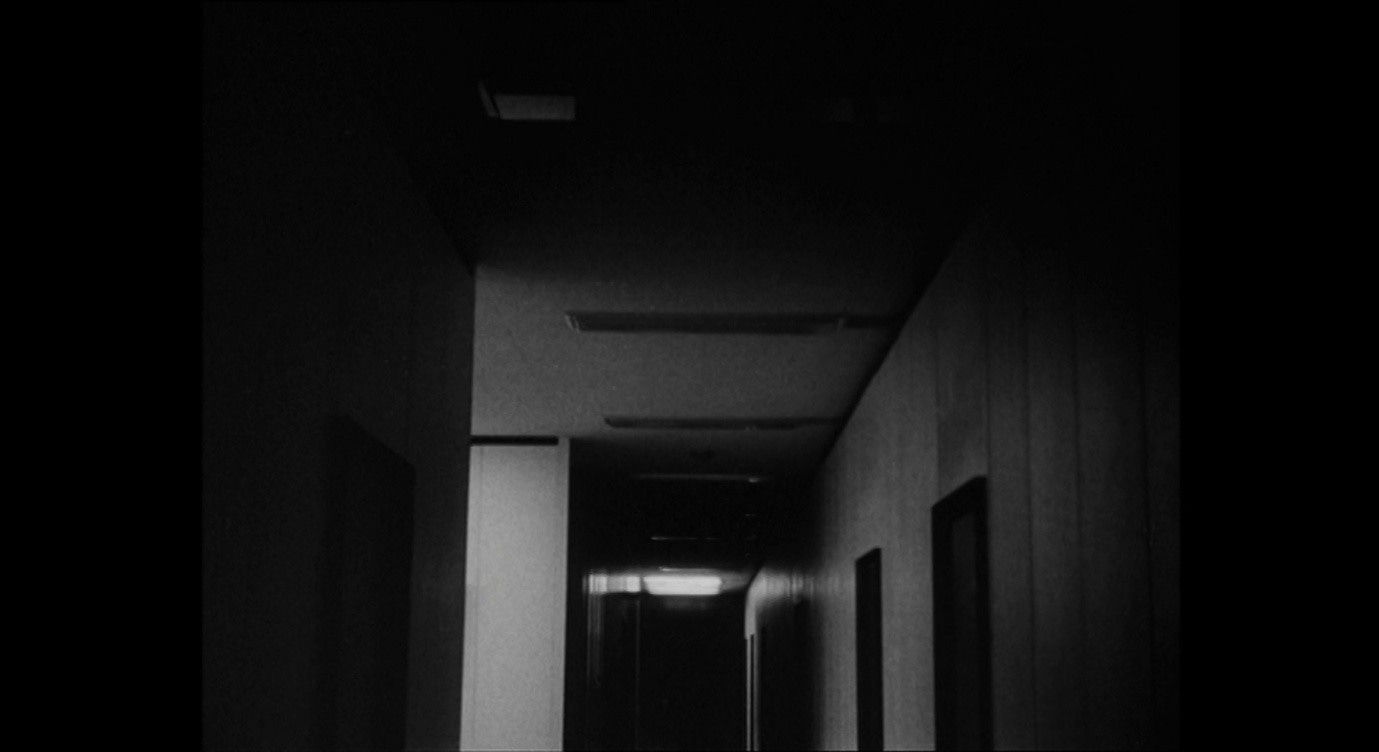

As she staggers along the corridor towards Corrado’s room, she clings to the wall with each step.

She is not in danger of falling to the floor, but of falling through it. In Mario’s apartment, she stood in front of the grey haze of the frosted window and raised her hands as she described the ground falling away from her.

That blank void is all around her now, and her hands clutch at any solid object for stability. At the same time, the film sustains the ambiguity of Giuliana’s fear of and desire for an amorphous reality. Is this wall a refuge that keeps her anchored in the world or an obstacle that keeps her trapped in it? Is she clinging to the wall for safety or bumping into it as she tries to break free?

Corrado reaches out his hand to support her, but she avoids it and walks past him on her way to his room: she wants to be with him, near him, but (at least for the moment) she does not want to touch him.

The screenplay comments, ‘the only concrete thing before her eyes is him, Corrado.’2 And yet, in the finished film, she pointedly refuses physical contact with him, as though wanting to deny his concreteness. Like Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night (see Part 23), ‘denying [her] children, resenting them as part of a downright world she sought to make amorphous,’3 does Giuliana find Corrado too concrete? Or is it the opposite, contradicting the screenplay’s stage direction in a different way: is Corrado too nebulous, too unstable, to cling to in this moment of crisis?

There is something chilling about the suddenness of Corrado’s appearance at the end of the corridor. We have just seen Giuliana begin to run up the stairs from the ground floor; now we cut directly to the third-floor corridor, where Corrado emerges from his room a few seconds before Giuliana arrives.

Corrado is positioned at (or as) the vanishing point towards which Giuliana is heading. If the wall she grasps at is both a refuge and a barrier, the lines of the image are both guiding her to safety and leading her to danger. Corrado is there for her, available and sympathetic, but he also looms ominously on the horizon, like the spectral sailor on the Tulipa. His image is reflected in the overhead light-fittings, endlessly repeated, anonymised, and de-constructed into its component parts, making Corrado into a man of fragments and illusory images, not what he seems and not at all concrete. Although the clichés of the adultery drama have been subverted in some ways, Giuliana’s story is about to lapse into those same clichés with a sad inevitability. She will, as she phrases it later on, ‘succeed in becoming an unfaithful wife,’ but she will fail to get the help she was actually looking for.

Rolando Caputo argues that this shot of the hotel corridor inspired the numerous similar shots in Godard’s Alphaville.4

In 1964, speaking to Godard about Red Desert, Antonioni described his encounter with an early form of artificial intelligence, which he called ‘one of the most extraordinary discoveries in the world’:

It was in a tiny box, mounted on a load of tubes: there were cells, made up of gold and other substances, in a chemical solution. These cells have a life of their own and have certain reactions: if you walk into a room, they take on one shape, whereas if I walk in, they take on another, and so on. In that little box there were a few million cells, but from such basis you can actually reconstruct a human brain. […] [I]t was so incredible that at a certain point I couldn’t follow [the scientist’s explanation] anymore. Yet, a child who has played with robots from his earliest years would understand perfectly; such a child would have no problem going into space on a rocket, if he wanted to. I feel very envious of such people. I really wish I were already part of that new world.5

Godard’s take on the ‘new world’ in Alphaville, though inspired by this conversation, is very different from Antonioni’s. Rather than marvelling at the AI brain and wanting to join the younger generation on some intersidereal mission, Godard pictures the futuristic city as a dystopia in which love, poetry, and other ‘illogical’ things are punishable by death. We might think of Giuliana when we hear about the Alphaville inhabitants who cannot adapt to the new order and commit suicide, or when a poet cries out, just before being executed, ‘We see a truth which you, the normal ones, no longer see!’

The outsider, Lemmy Caution, comes here to destroy the computer overlord, Alpha 60, and when he travels into the stars at the end (in his car) it is to escape the future, not join it. Where Antonioni mourns his own inability to adapt, Godard revels in it as a sign of humanity persisting against the encroaching robots. Where Antonioni portrays the escape (via pink-sanded beach or sun-proof spaceship; see Part 35) as a self-dismantling fantasy, Godard uses it as an allegory for re-discovering love and hope amidst the darkness of the modern world.

Like Fellini in 8½, Godard conjures a mood of science fiction by filming at night with artificial lights floating eerily in the pitch-black void.

Antonioni used a similar method to make Cinecittà seem like an other-worldly space in Il provino, with glowing strip-lights marking the curves of the road that leads to the studio.

The mid-60s film industry is here figured as a place of supreme artifice, building intricately programmed screen personae just as a scientist might build a robot that cannot be distinguished from a real human being.

Princess Soraya does not seem destined to survive this process. Like the journalists who get stuck in a bleak side-alley of the studio, shut out by a row of locked doors, we end up outside the studio with a very un-glamorous view.

In the final shot, we see the futuristic road to Cinecittà transformed into a mundane driveway by the onset of the grey dawn. Finally, we are left at the side of the road, watching the traffic race past us; in some sense this is where Soraya, emotionally and psychologically, remains while her ‘star’ identity performs in the subsequent sections of I tre volti.

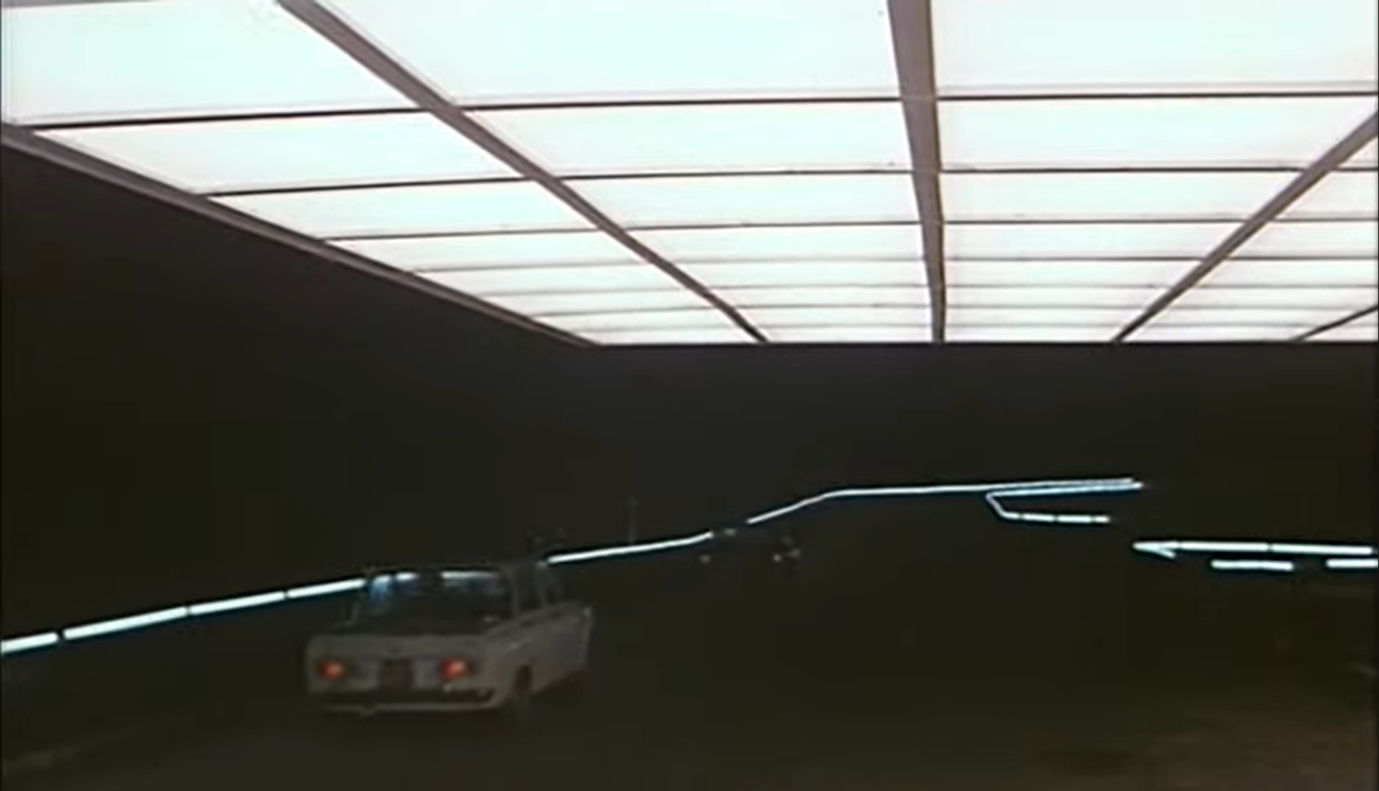

Godard briefly shows us a view of Alphaville in daylight, not lit up with mundane clarity but shrouded in fog (or smog).

The alternately be-nighted and be-fogged exteriors mirror the interior settings, where the familiar seems infused with dread. Richard Brody quotes and comments upon Godard’s description of his approach:

‘The sensitive film gives the image a lunar aspect,’ Godard explained. ‘It was very important to me. I wanted an expressionistic style. In filming things that we see every day, I wanted them to arouse fear. Without cheating. The things are there. One looks at them. And suddenly, one discovers that they are not at all as one thought.’ The camera in Alphaville shows not a distortion of reality but a hidden or inner reality: what appears to the naked eye as an adequate brightness is revealed in fact to be a dangerous darkness, exactly as a person of apparently healthy aspect can be revealed by X-ray or MRI to be seriously ill. Here, Godard used the movie camera as a scientific instrument, attempting to put his faith not in the way things appeared but in what filming them might reveal.6

These effects are most apparent in the corridor shots, where the ‘adequate brightness’ seems to partake of the same obscurity (night and/or fog) that we saw outside. Alpha 60 is housed within a labyrinth of identical corridors, much like the one in Corrado’s hotel. ‘Le jour se lève!’ declares one of the computer’s enforcers as the lights flicker on in response to his and Lemmy’s arrival; this is how the sun rises in Alphaville.

The camera prowls behind Lemmy Caution as the croaking voice of the super-computer declares each room occupé or libre.

These corridors, in which the language of occupation and liberation is used for exclusively bureaucratic purposes, are rhymed visually with Alpha 60’s data stacks.

In this new world, we are all just pieces of code stored in and sorted by a vast computer. There is an air of paranoia in the way the mirrored ceilings capture Lemmy’s image as he walks beneath them: the building not only senses his presence but keeps a close eye on his every step.

Indeed, Alpha 60 wields total control over the human slaves who circulate through its corridors. When Lemmy causes the computer to self-destruct, the humans lose control of their bodies, flopping from wall to wall as they slowly die.

Like Giuliana, Natasha struggles to make her way down these corridors, clutching at one wall then another as though clinging to this ordered, logical world she has come to depend on. But Lemmy keeps grabbing her and holding her close to him.

Unlike Corrado, Lemmy is figured as a genuine saviour to this woman, taking her out of Alphaville and teaching her, in the film’s final moments, to say ‘I love you.’ In other words, he accomplishes what the doctors failed to accomplish in the clinic with Giuliana: he teaches this sick woman how to love.

Where Godard’s camera dollied aggressively up and down the corridors, joining Lemmy Caution in his quest to penetrate and dismantle these oppressive structures, Antonioni’s camera stands perfectly still and watches Giuliana struggle onwards.

The reflections in the ceiling, as in Alphaville, make the characters seem ‘watched’ by their environment, but the tone here is less paranoid: the people in Red Desert are seen with eyes like Ugo’s, dispassionate and lightly judgemental.

There is no evil computer bent on destroying dissidents, just a world of inescapably reflective surfaces reminding us how easily we can be broken up and replicated. The Antonioni corridor, or the street or pathway that extends towards a vanishing point, does not invite the camera to travel down it in the pursuit of any particular goal. It shows us a static set of parallel lines that seem – even when we can see the end of the corridor, as in the hotel in Red Desert – to go on forever. If there is someone walking down this path, they are not going anywhere, they are just ‘going on’ with their current existence. The street-sweepers in N.U., Paola and Guido at the Idroscalo in Story of a Love Affair, Aubrey setting out on his quest for fame in I vinti – whether still or in motion, these people all seem locked into and trapped between those parallel lines.

Lemmy and Natasha, by contrast, are last seen speeding towards a better place (at the end of a long road) with the camera keeping pace behind them.

‘I love you,’ says Natasha, cathartically, at the end of Alphaville. ‘You don’t love me, do you?’ says Giuliana to Corrado, moments after entering his hotel room, in a tone that suggests she expects neither an answer nor any form of catharsis at the end of this journey.

Next: Part 37, An incurable need.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Wenders, Wim, My Time with Antonioni, trans. Michael Hofmann (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), pp. 3-4

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 489

Fitzgerald, F. Scott, Tender is the Night (1934 edition), ed. Arnold Goldman (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 270

Caputo, Rolando, Commentary track, Red Desert (DVD, Madman Entertainment 2006)

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 291

Brody, Richard, Everything is Cinema: the Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2008), p. 280