Everything That Happens in Red Desert (17)

Giuliana's illness

This post includes some discussion of suicide and spoilers for Bellissima and Senso.

‘Perhaps the most pervasive and troublesome of all the unresolved mysteries,’ says Millicent Marcus in her analysis of Red Desert, ‘is the origin of Giuliana’s neurosis.’ She goes on to unpack (but not resolve) the nature and significance of this mystery:

Is it her unfulfilling family life, or some trauma in her past, or the inhumanity of the technological world to which Giuliana reacts as if she were an exposed nerve, registering its every assault on her fragile sensibility? Antonioni’s refusal to cast blame bespeaks not only his general indifference to questions of causality, but also his desire to posit the analogy between Giuliana’s vision and his own – an analogy that would suffer from too technical an explanation for her illness. If Giuliana’s neurosis were presented as a specific clinical condition attributable to concrete causes and susceptible to a given psychiatric treatment, we would dismiss her vision as just one more pathological symptom, rather than a viable model for Antonioni’s own aestheticizing approach.1

There are two crucially important insights about Red Desert here. One is that Giuliana’s illness is at the centre of the film, a pervasive and troublesome topic with many possible causes. The other is that the precise nature and origin of this illness are left uncertain so that the film can inhabit Giuliana’s ‘vision’, her perspective. As viewers, we are free to diagnose this character if we want to, to speculate about the causes of her problems and even to prescribe a treatment for them. But the film itself simply represents her point of view; what it shows us, as a work of art (in its ‘aestheticizing approach’), is what Giuliana sees, as a suicidally depressed person. I have made this point before, but it is worth bearing in mind – especially in the terms used by Marcus – as we look at the present sequence.

While following the development of Giuliana’s affair with Corrado during their road-trip to Ferrara and Medicina, we also learn more about her recent breakdown and her time in the clinic. She reveals herself hesitantly, unsure of how Corrado will respond. The conversation about Giuliana’s mental illness is triggered by a conversation about relationships – specifically how one relates to non-human creatures, and the overlap between loving them and eating them – and what she says about her illness in this sequence centres around her relationships with people, animals, objects, and the world in general.

Near the beginning of the Ferrara sequence, as Giuliana and Corrado walk past a fishmonger selling live eels, one of the eels falls to the ground near Giuliana’s feet. This is made clear in the screenplay, but the film obscures the action through a disorienting series of out-of-focus long-lens shots. We know from the dialogue that the customer wishes to buy a ‘live’ product, but we cannot be sure what the product is, or why Giuliana runs away, or what Corrado is laughing at. On the left in the background of the first shot below, we can see the eel being moved from one receptacle to another, but only eagle-eyed viewers (who are also attending to the background dialogue) will pick up on this.

After the encounter with the eel, a single wide-angle shot, perfectly focused, shows Giuliana hurrying through a portico. The clarity of this image throws into relief the haziness of the preceding shots, thereby accentuating our confusion over Giuliana’s behaviour.

While the action in this series of shots is not clear, the disorienting photography shows us, with great economy and clarity, how it feels not to be able to perceive or interpret the world we live in – to sense, in fact, that something important and dangerous is happening in the background of our story, in the part of the story that has been left out-of-focus. A moment later, Giuliana will begin talking about her fear of de-stabilisation, of blurred definitions and boundaries. Corrado talks about transparent fish in the lower depths of the sea, and she begs him not to tell her about such things: ‘They make me afraid. You can’t imagine what fears I have [le paure che ho io].’ As Giuliana says the word io, she stumbles, pauses, and looks down to see the wooden slats beneath her feet see-sawing back and forth. Corrado seems faintly amused by this on-the-nose symbol, which trivialises Giuliana’s angst. An eel that cannot stay in one place; dry land crawling with sea-creatures; fish you can see through, and therefore perhaps cannot see…these ‘wonders’ that amuse Corrado fill Giuliana with horror. They are reminders that what we think of as reality can disintegrate, that the boundaries between things are porous and changeable.

Inside the apartment, during the few minutes when Mario’s wife leaves them alone, Giuliana talks to Corrado about her car crash. She introduces the topic by asking Corrado whether he already knows about it. As in the previous scene, his response is vague, and he says, ‘It wasn’t serious, was it?’ On one level, he is being tactful (it would be impolite to say, ‘Yes, Ugo told me how deranged you are’) and giving her the option of playing down the seriousness of what happened. But there is also a sense, in this conversation, that it is better not to speak about such things too openly, that to bare one’s soul about a traumatic experience would not be (as Ugo might say) decoroso. This is why, for instance, Giuliana begins the conversation by asking, ‘Tell me the truth, has he spoken to you about it?’, without specifying which ‘he’ and which ‘it’ she is referring to, once again forcing Corrado to ask for clarification. She then says that she knew a woman; Corrado asks where; she says ‘there’, and he has to fill in the blank: ‘You mean in the clinic?’

It is in keeping with this decorous, oblique mode of discourse, and with Corrado’s polite but restrained expressions of interest, that Giuliana displaces her story onto a fictional ‘other woman’. Besides the stigma attached to mental illness and the consequent risk of embarrassment for Giuliana, she is considerately placing less responsibility onto Corrado. These problems are not hers but the other woman’s, so he has no obligation to care about them. But this act of displacement also frees Giuliana to speak frankly (‘She was very ill’). Away from the factories, away from her home, and displaced from her own self, Giuliana can finally discuss her problems. The very fact that such self-alienation is a prerequisite of self-expression also hints at the nature of those problems.

The other woman in the clinic, says Giuliana, ‘wanted to have everything [voleva avere tutto].’ Her doctors told her she should ‘learn to love.’ Specifically, Giuliana then explains, this woman was advised to ‘love a person or even a thing: her husband, her son, a job, or even a dog [my italics]… But not husband son job dog trees factories…’ In the transition from the first list to the second, the loss of the possessive pronouns and indefinite articles is supposed to indicate where the patient was going wrong. Specific, discrete individuals become abstract concepts that blur together. The addition of two new items to the second list – trees and factories – introduces plural nouns and reminds us of the opening (out-of-focus) shot of the film, in which the camera panned from a cluster of trees to a cluster of factories.

According to the doctors, it is dysfunctional to perceive the world in these terms. If the mind’s eye is a camera, it must learn to focus, to engage with one thing at a time, and to distinguish between things.

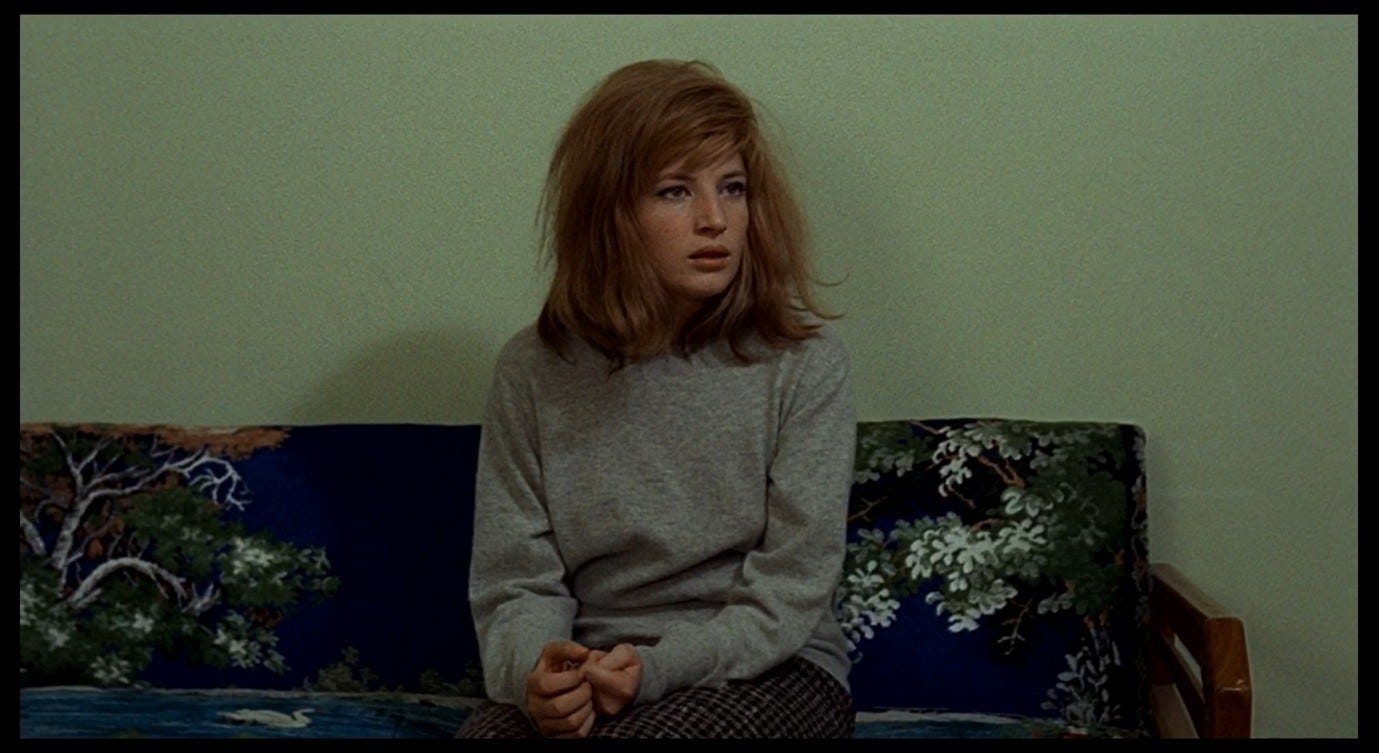

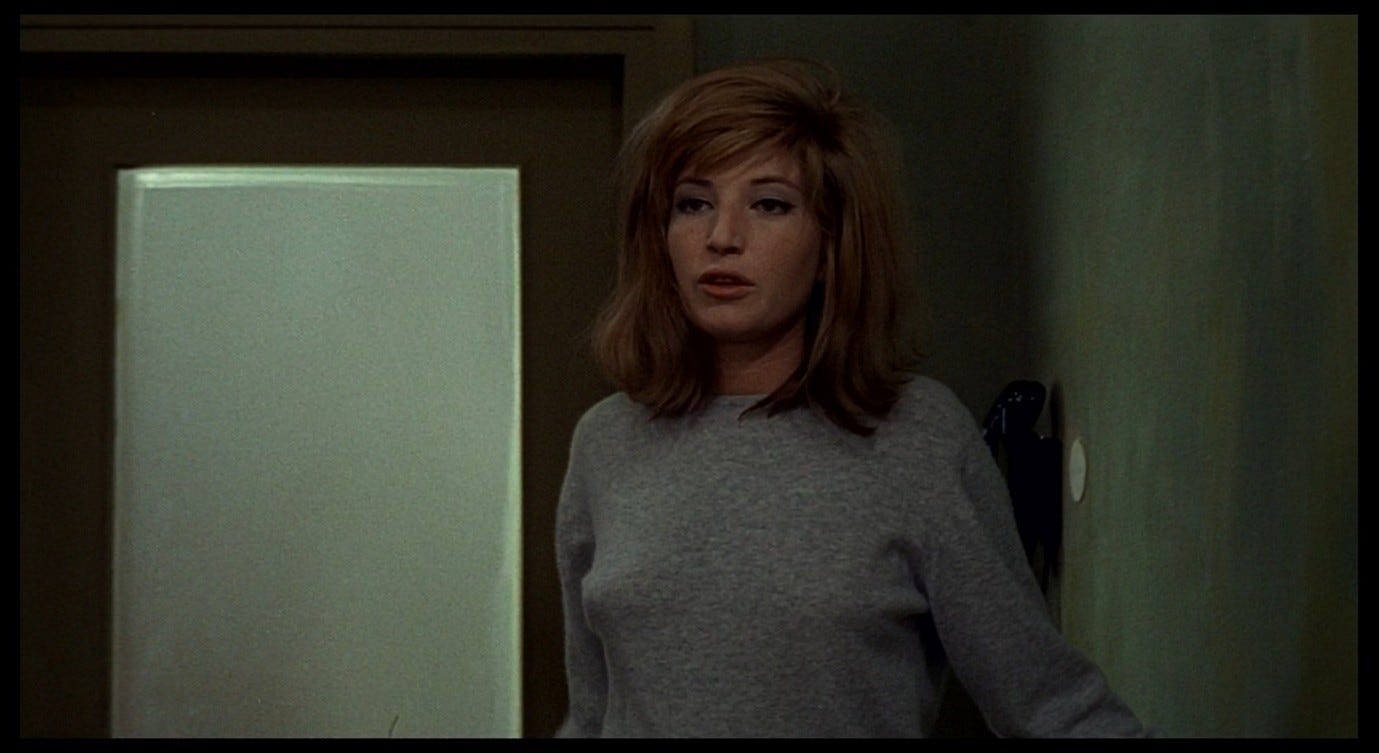

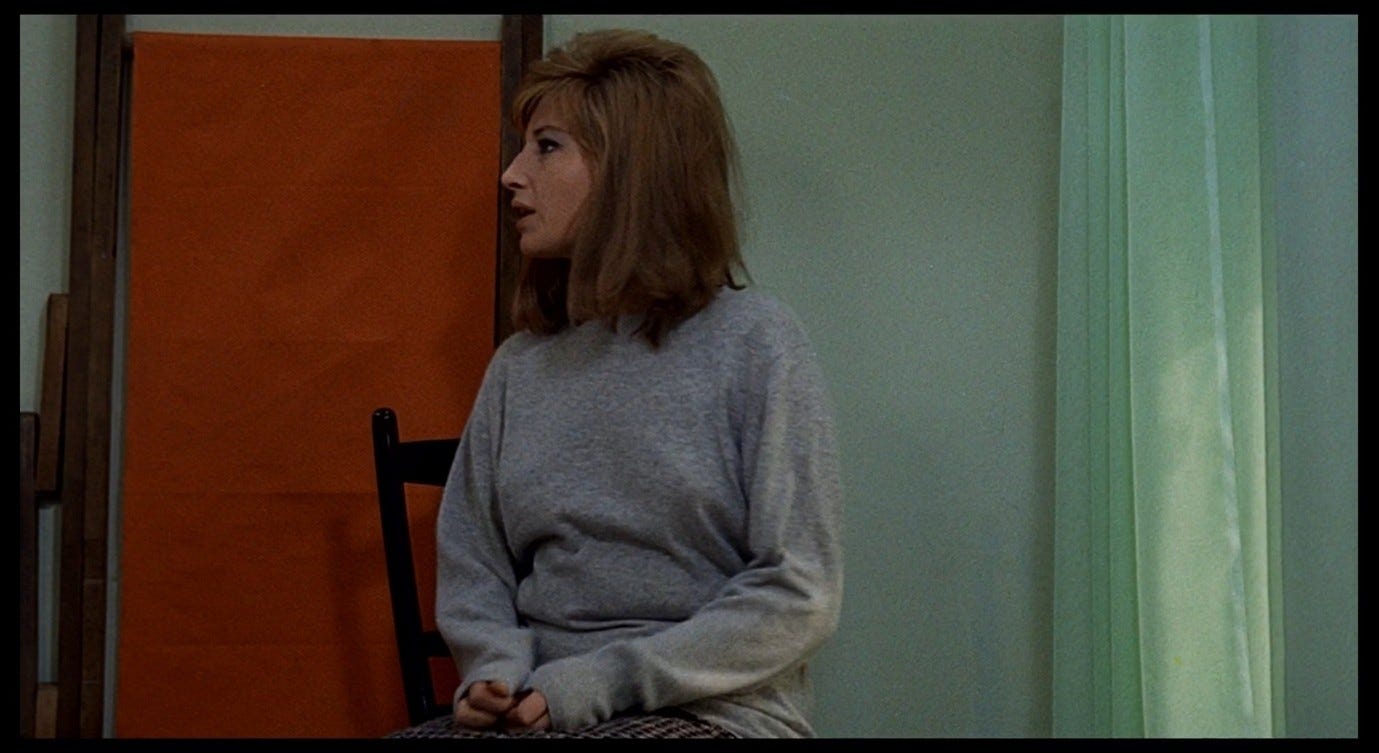

When Giuliana begins to talk about this ‘other woman’, she leans down to stare at the fabric on the sofa, rapping her knuckles over it and tracing the patterns with her fingers.

The camera observes these symptoms closely, intrusively, as does Corrado.

There is a sense of embarrassed self-consciousness in the way Giuliana then stops fidgeting and sits up straight.

Almost immediately, though, she begins playing with her fingers, alternately clutching her left thumb and then letting her hands splay out again.

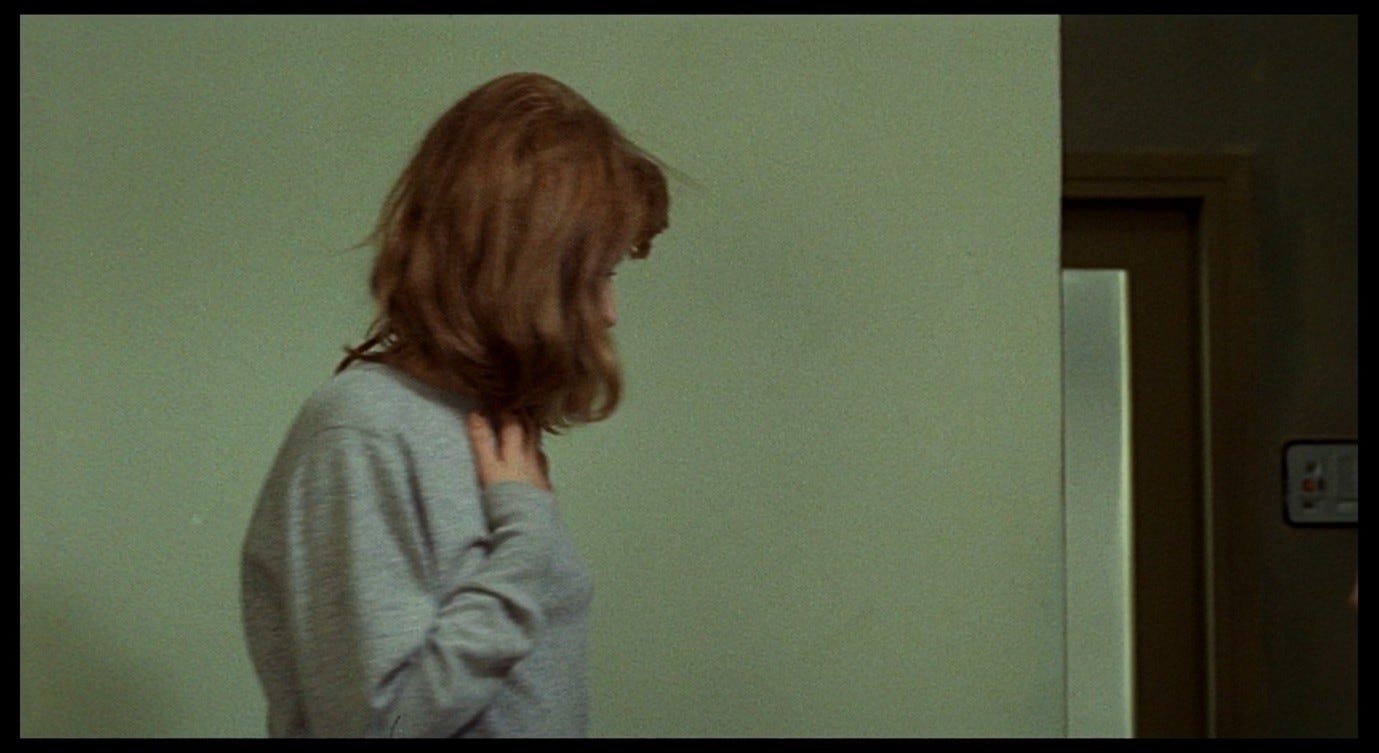

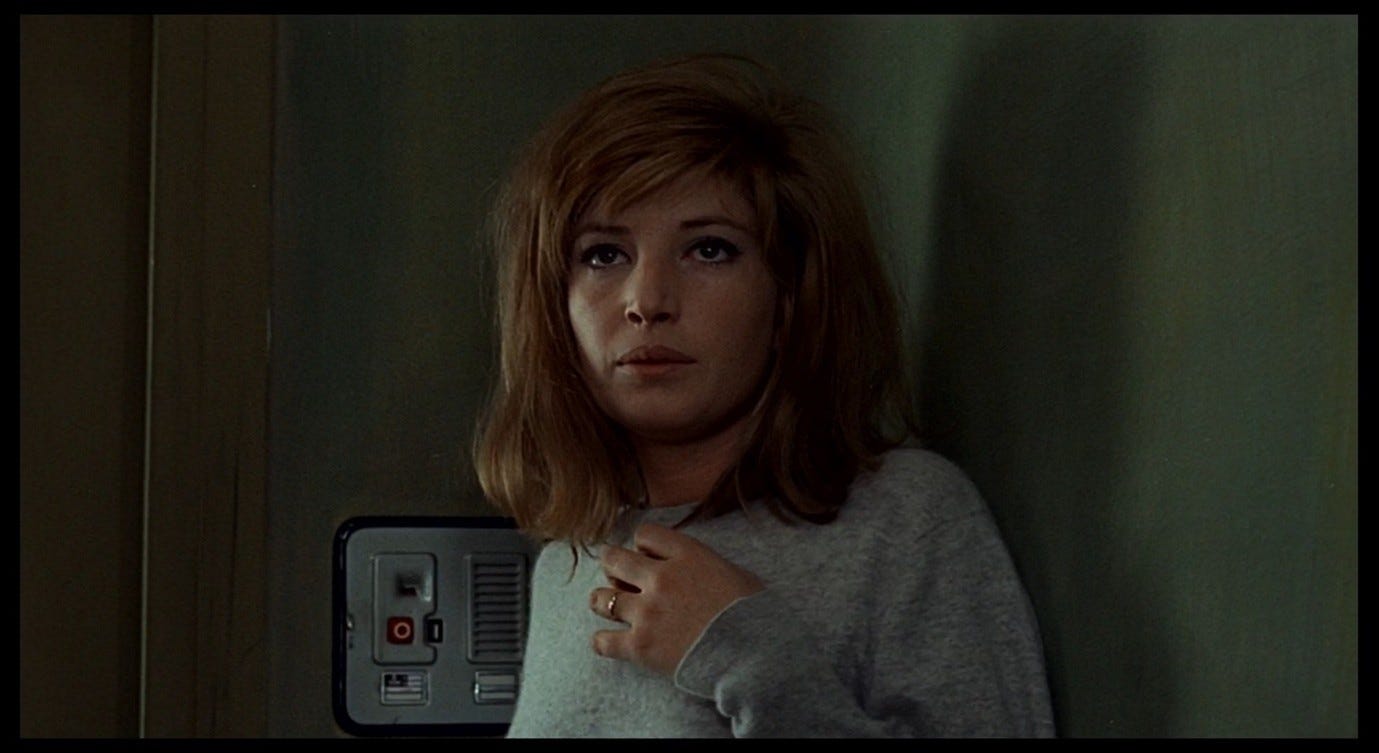

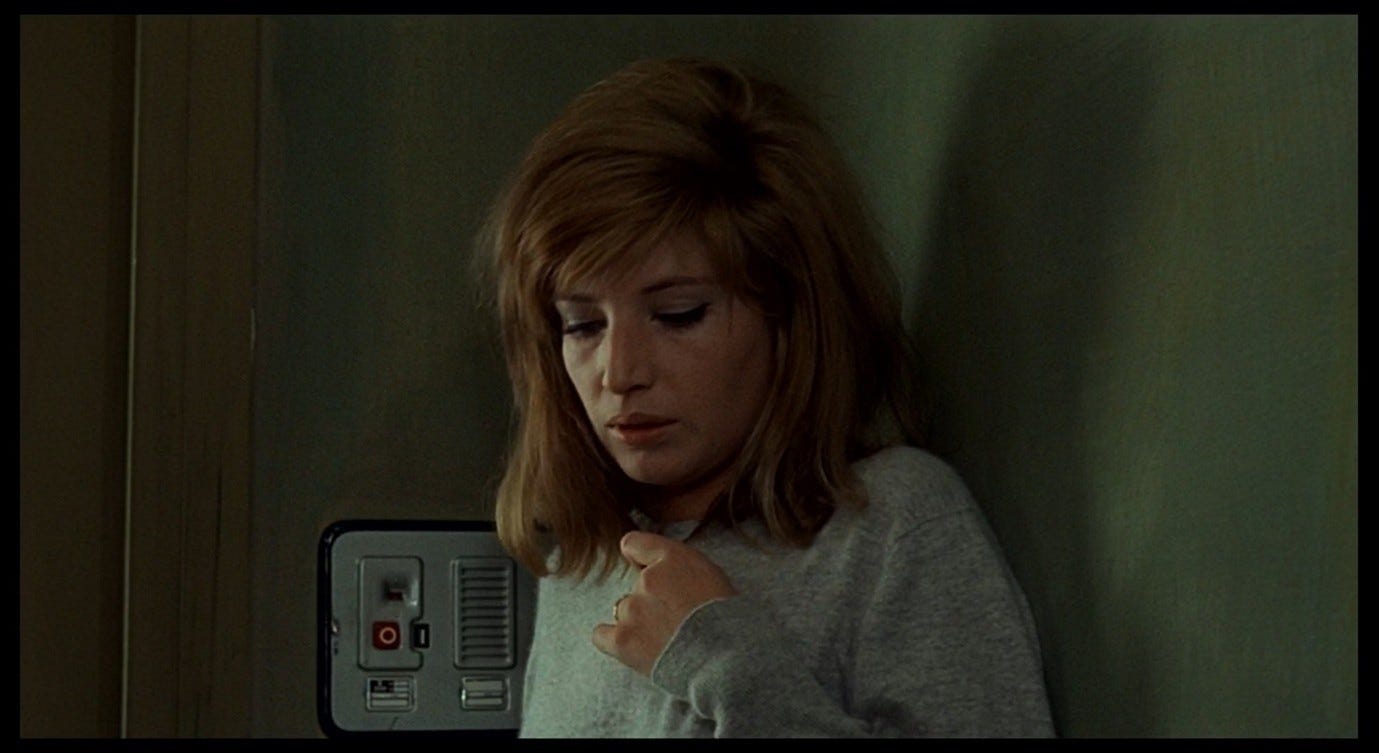

She is trying to follow the doctors’ advice, focusing on a single thread, clinging to a single digit, but her hands will not stay still and the fingers keep combining or exploding. Nor can she stay in one place. She gets up, her hands fidgeting at her throat, chest, and sweater.

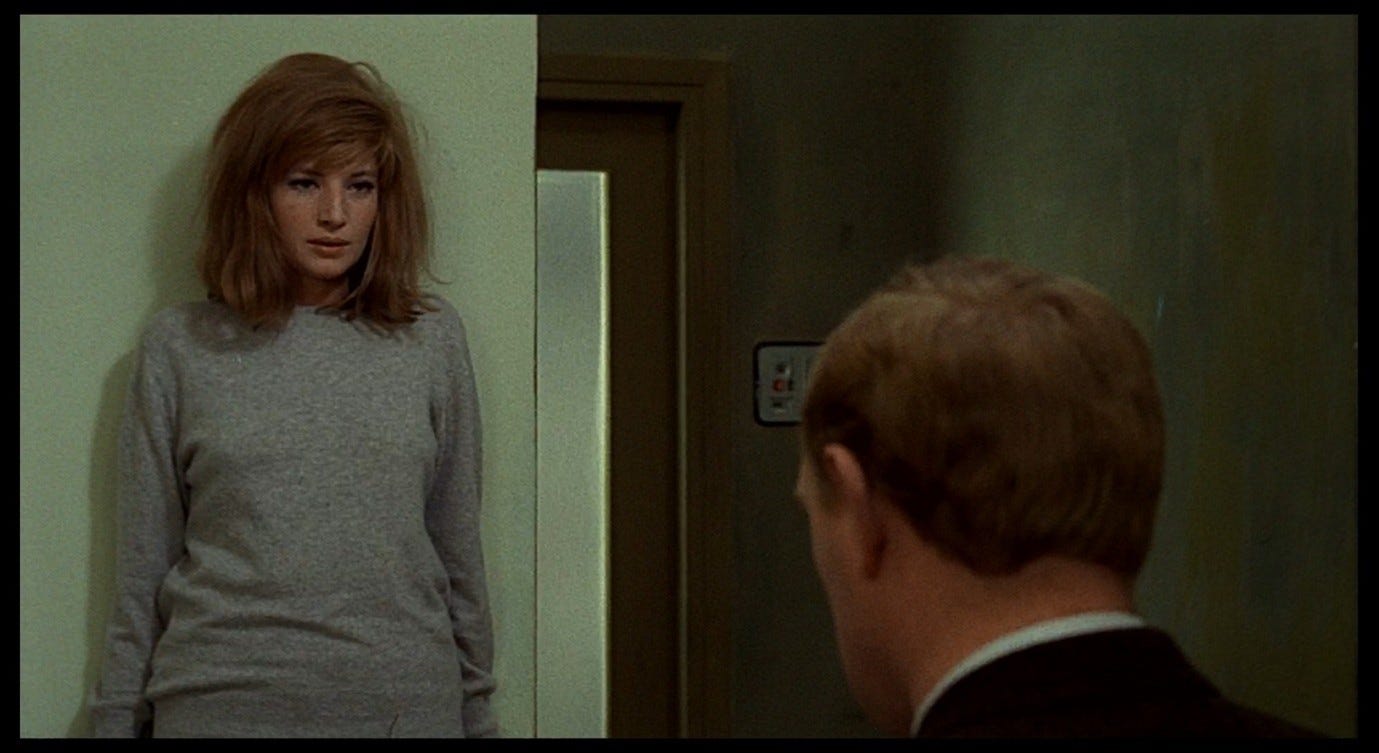

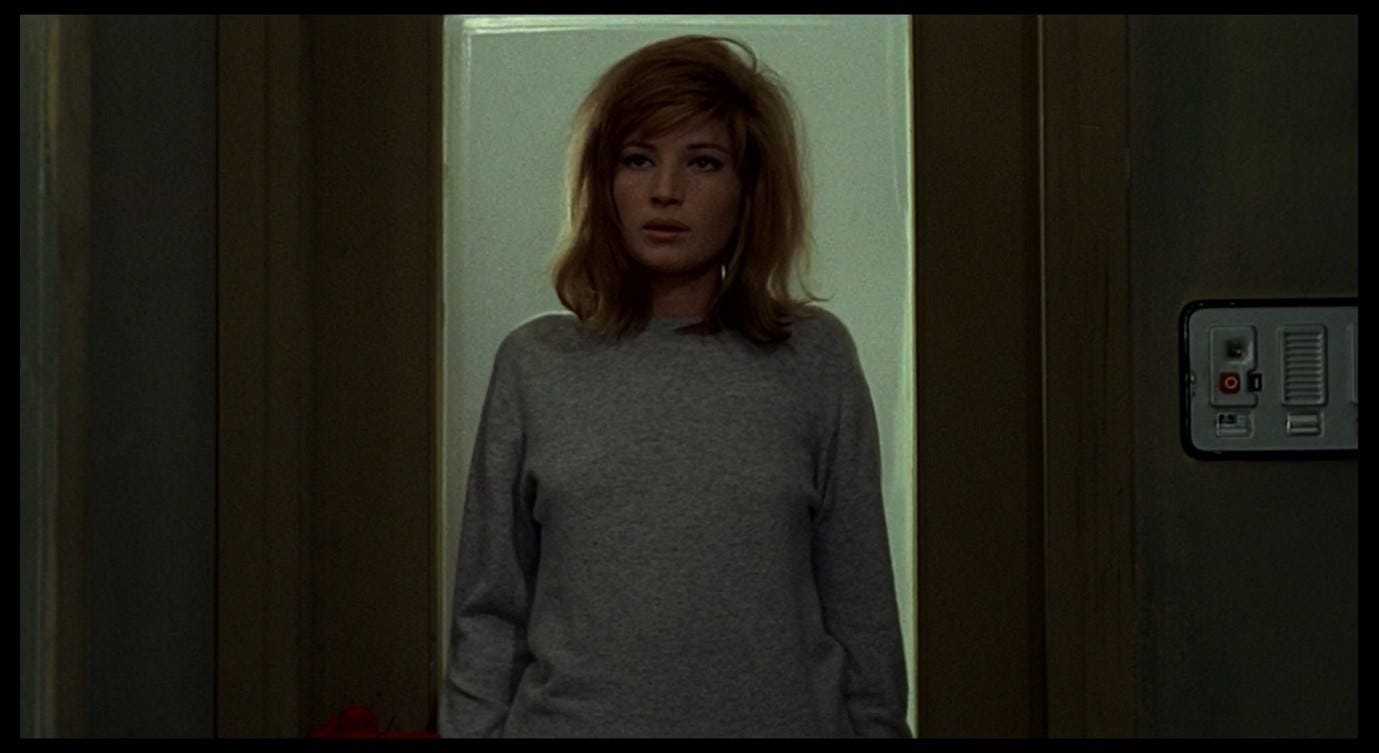

She stands against one wall as she recites the list of discrete loved-ones prescribed by the doctors, then backs fearfully into another, darker wall as she recites the second, more amorphous list.

The still-intrusive camera pursues her relentlessly as she backs into the wall, in a rapid dolly-movement, looking at her from a low angle like a four-legged creature closing in for the kill. Her terror seems in part a response to this predatory all-seeing eye. The reverse shots of Corrado looking at her continue to portray him in an ambiguous light.

He perhaps seems attentive and sympathetic, but without being over-solicitous. Or he perhaps seems imbued with a subtle air of menace. We have to wonder – as with his pursuit of Mario – what he is hunting for and what he plans to do when he catches it. But his perspective overlaps with that of the camera, and with ours as well: why is Antonioni making this film and why are we watching it? What do we want from this woman? The doctors in the clinic taught her how to relate to the world, how to ‘love’ it; but we might ask critical questions about how those doctors, Corrado, the camera, and the cinema audience relate to (‘love’) Giuliana.

Joseph Luzzi argues that Red Desert’s

principal visual tension lies in the contrast between subjectivity and objectivity, between free indirect point-of-view shots that give us Giuliana’s perceptions, and tracking shots that render her a pointedly sexual object. These tracking shots deprive her of the very subjectivity that filters the film’s world into such weirdly compelling colors and compositions. For example, when Giuliana and Corrado go on a recruiting trip to a worker’s apartment in Ferrara, Antonioni’s camera follows her movements with almost suffocating precision.2

I think the camera movement analysed above both illustrates and challenges this reading of the film. The gaze that pursues Giuliana is indeed suffocating in its precision, but that precision lies in the precise tracking of Giuliana’s emotions. If the camera did not follow her around the room, and did not take the trouble to dolly so quickly towards her when she backs into the corner, we might not share in Giuliana’s sense of panic. Rather than depriving her of the subjectivity that filters the world around her, this camera movement makes Mario’s apartment alive with predatory danger, which is how Giuliana experiences it. And Luzzi is right that there is a sexualising element to the way the camera looks at Giuliana, but I do not think it is pointedly sexual in most instances. We sense that Corrado is attracted to her, and that he plans to do something about this, so the predatory danger embodied by the camera reflects this; but again, I would argue that it is not Corrado’s desire, but Giuliana’s fear of Corrado’s (and, earlier in the film, Ugo’s) desire that we are being asked to empathise with. Luzzi goes on to say that Antonioni has a tendency to keep sex at bay in his films because it ‘represents a possible threat to his controlled compositions […] we do not feel the heat of bodies; we see instead the awkward chaos of desire.’3 This describes Giuliana’s point of view as well: as she describes the terror of her love-connections with others, the rapidly moving camera is like the body-heat between her and Corrado, the awkward chaos of desire threatening to bring them together. The threat posed by sex is, as Luzzi argues, a threat to the ‘control’ one has over the composition of oneself and one’s environment, but it is also more complex than that, and its complexity will be suggested, later in Red Desert, by those ‘weirdly compelling colours and compositions’ that emerge from Giuliana’s subjectivity.

It is particularly striking that the learning process recommended to the woman in the clinic is framed as ‘learning to love,’ as though someone who loves husband-son-job-dog-trees-factories does not in fact love at all. There is an implicit question here about the definition of love, or of human sentiments in general, and Corrado follows up on this by asking whether the woman in the clinic ever told Giuliana about her feelings. In the screenplay he says, ‘Ma che cosa si sentiva?’; in the finished film, he says ‘Ti ha mai detto che cosa sentiva?’, literally ‘Did she ever tell you what thing she felt?’ Corrado does not presume that Giuliana knows what this other person felt, but acknowledges that she would need to have been told, tactfully playing along with the game of displacement. He is also affirming that people need to express their feelings in order to form a connection. The woman in the clinic might not have expressed herself, leaving Giuliana with no insight into her condition and no way of bonding with her. If Giuliana does not express herself to Corrado, they cannot be friends or lovers…or anything. He stands up as he asks the question, bringing himself closer to her, urging her to confide in him.

This is another definition of ‘how to love,’ and like that of the doctors it focuses on the need for clarity. The object of love must be defined and distinguished from others; sentiments must be clarified and put into words.

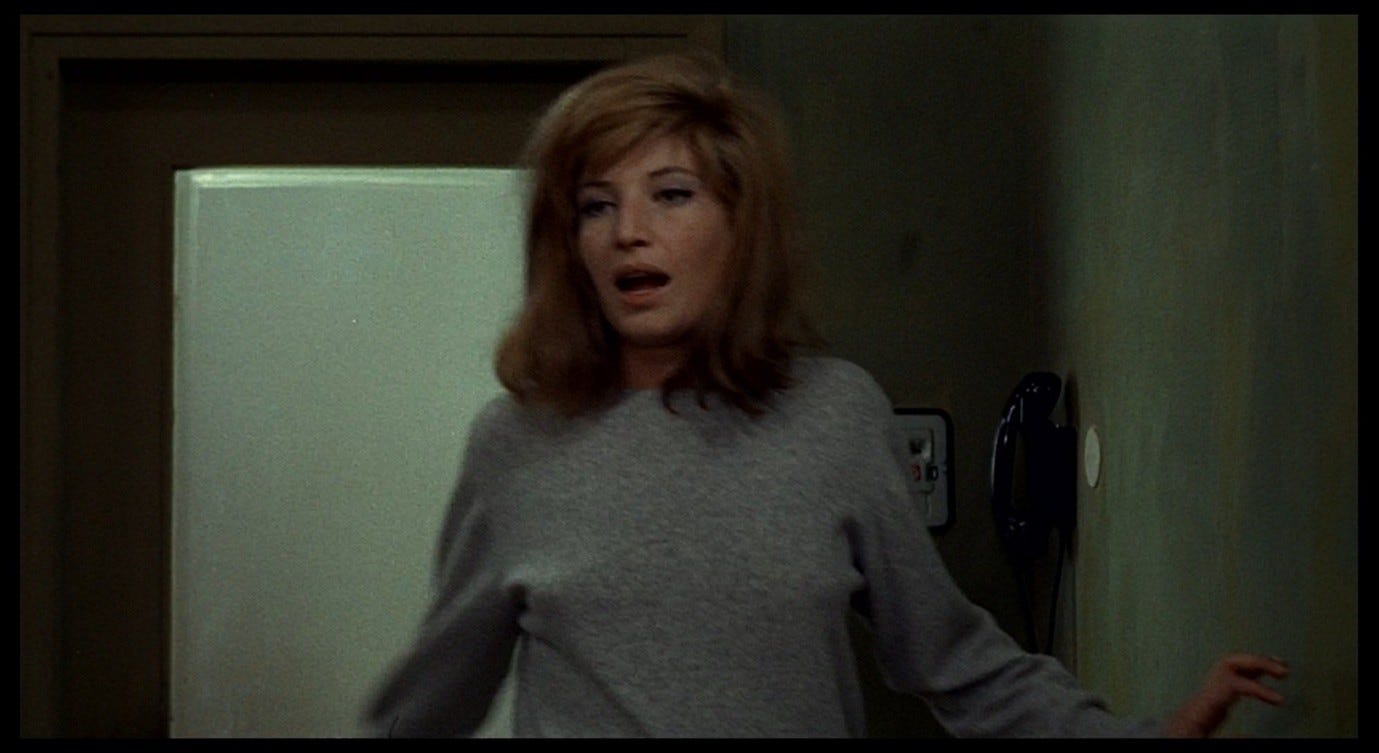

Giuliana, who has been looking at Corrado with an expression of panic, now looks down and seems to calm herself, preparing her explanation.

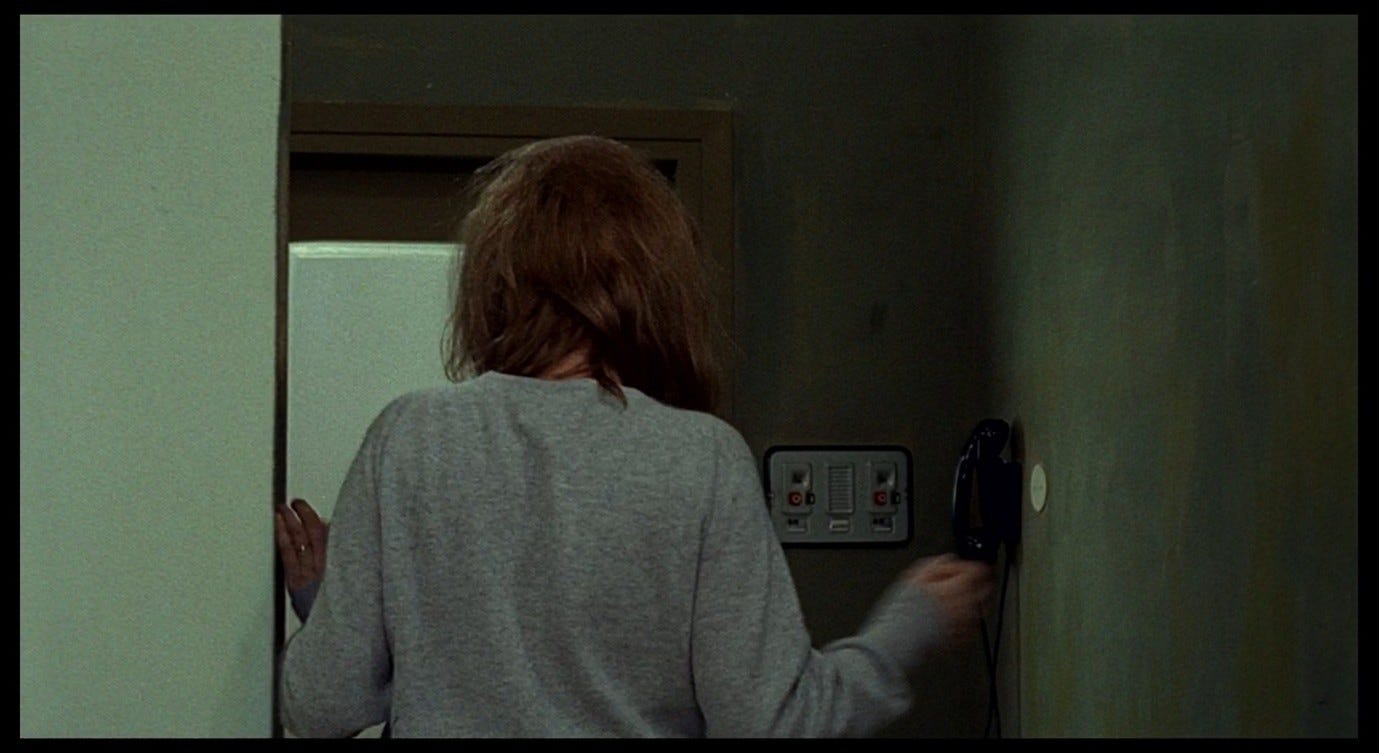

She frames herself against the frosted glass in the doorway and immediately begins talking about the disintegration of her surroundings.

The woman in the clinic, says Giuliana, had lost the ground beneath her feet. This reminds us of the unstable slats in the walkway a few minutes earlier, and the frosted glass reminds us of the out-of-focus images during the encounter with the eel. After saying ‘Le mancava il pavimento’ in one breath, rushing the words out before she can stop herself, Giuliana then stammers over the next two ‘p’ sounds as she says, ‘L’impressione di scivolare su un piano inclinato [my italics].’ Both the inclined plane she is falling down and her impression of this plane are hard to cling onto. They elude both her grasp and her powers of expression. Was this really how she felt, or has she not found the right words? Was this really what happened to her, or did she mis-perceive it?

Giuliana’s description of sinking ‘down, down,’ and drowning – or being on the point of drowning, ‘lí lí per affogare’ – is familiar from her nightmare earlier in the film. Now she holds up her hands, palms outward, again seeking to illustrate her point visually: ‘e non hai niente,’ she says.

The screenplay suggests that the hand gesture clarifies her statement, indicating that this woman had ‘nothing to hold onto,’4 but the comment ‘non hai niente’ is more ambiguous than that. It suggests that the woman ‘had nothing’ to hold onto, but also that she simply ‘had nothing’ full stop; and as well as suggesting that there was nothing to hold onto, it might also suggest that the terrors she imagined were not really there, that she had no evidence to show her husband, for example, to prove that she really was sinking. The inability to rely on one’s perception of reality, the sense that one might be on firm ground and drowning, breathing normally and suffocating, happily married and completely alone – all at the same time – these ideas complement each other and coalesce in Giuliana’s outburst.

For a moment, the image of Giuliana framed against the hazy glass, with the dark-green door frame around it, her hands raised like someone descending a helter-skelter, makes us feel that we are watching her fall into oblivion. But then we cut to a two-shot including Corrado, who leans against the corner of the wall, with the rest of the neat and ‘tacky’ living room visible around Giuliana. The nightmare image is dispelled and undercut. Giuliana seems vaguely embarrassed as she puts her hands down, containing them at the centre of her chest, and steps away from the door. This is a characteristic gesture for her: a burst of intense feeling, then a sheepish retreat into normality.

Corrado’s questions – what about this woman’s husband, or her son? – seem sympathetic, sceptical, and accusatory at the same time. How can a happily married mother feel so alone? The question about the son, in particular, is spoken in a mawkish tone – ‘Not even…her son?’ – that is worlds away from the suffocating terror Giuliana has just expressed.

Her husband was elsewhere, she says (a point Corrado will follow up on later), and to the question about her son she responds with a dutifully affectionate tone (‘Him, yes’) before contradicting herself: ‘But this woman didn’t have a son.’ On one level, this is a half-hearted attempt to keep up the ‘other woman’ pretence, but Giuliana is also refuting Corrado’s sentimental preconception and offering a counterpoint to her own sentimental response: ‘Of course I love my son…but I also don’t have one.’ We have seen enough of her life at home to have some sense of what she means, and we will come to understand this more fully as the film progresses.

During this exchange, Giuliana has moved across the room, pausing very close to Corrado as she responds to his questions, and now she sits down again, facing the sofa where she was before.

This positioning is significant given that she now talks about having to explain something to herself, to this other woman: ‘When she left the clinic she was at a point [a un punto] where she asked herself: but who am I [ma io chi sono]? She had to have it explained to her…by me.’ Giuliana is looking across the room, towards the sofa, as she says this.

Near the end of the film, she will complain that doctors ‘talk to me about me,’ but that her illness affects her when she is alone. It is all very well for other people to assign an identity to her, but she needs one that works for herself as well. Her speech in Mario’s apartment helps to explain the problem, especially if we map the progression of her story onto her physical progress around the living room. When she was on the sofa, she began talking about her other self as a patient in the clinic, to whom the doctors explained things; she moved away from the seating area and framed herself against the frosted glass to recount her sense of disintegration, her total displacement and loss of identity; she denied her family attachments as she returned to the seating area; and now she takes up the place of this ‘other woman’, sitting across from the sofa she occupied at the start of the conversation. Having left the clinic, divested of concerned doctors and loving family members alike, she now has to explain to the original Giuliana who she is. It is as if she has one self in the clinic and another when she leaves; one self insofar as she is connected to other people, and another when she is alone. Her displacement of her own condition onto a different self indicates a desire to put that disturbed self behind her, to say (as she does to Corrado, hastily and nervously) ‘Now she is cured,’ and thus to be cured of being that person.

But this doubling also indicates the persistence of her condition. It was the other woman who was cured, not Giuliana. It was the other woman who received the explanation as to who she was, not Giuliana (who no longer identifies with that woman).

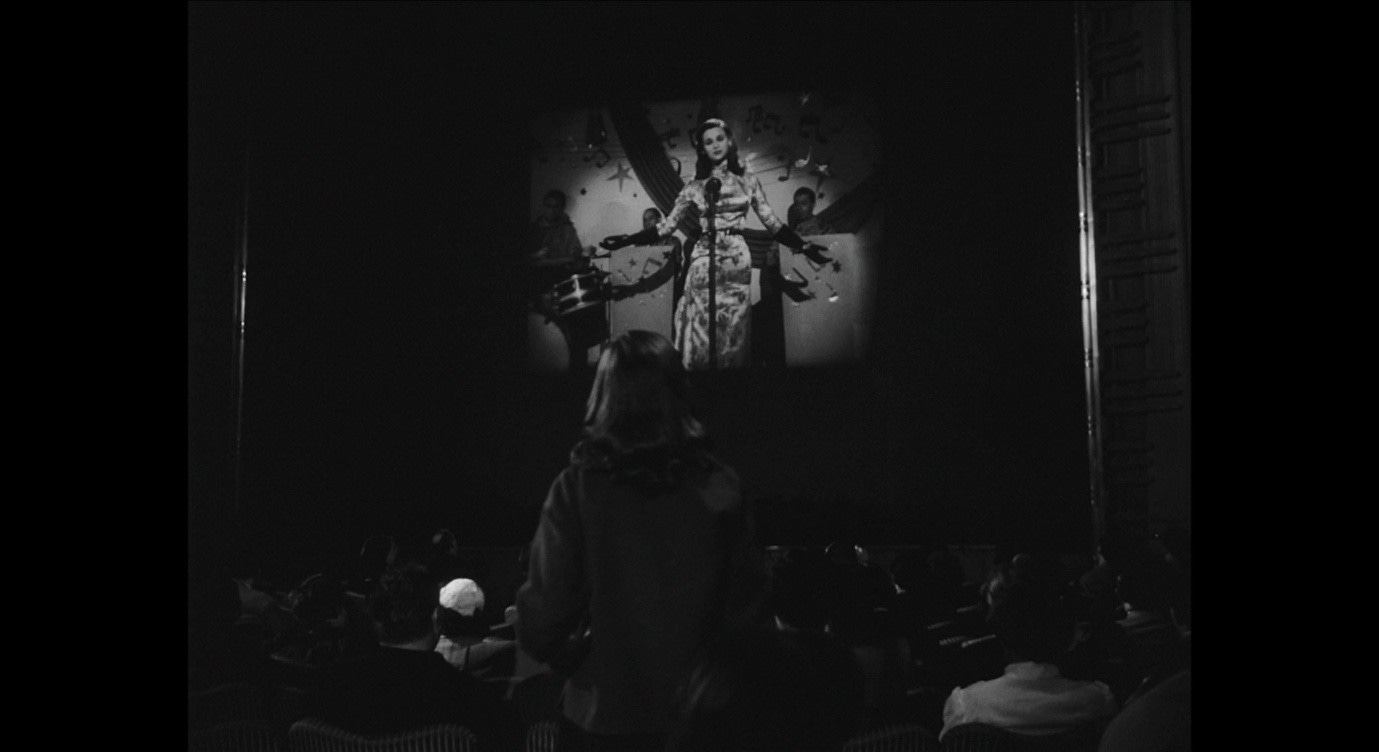

Clara Manni, in La signora senza camelie, saw herself on the cinema screen and had to keep repeating, ‘Sono io, io,’ meaning both ‘It’s me [on the screen]’ but also ‘I am “I”, I am myself.’

Clara was disturbed by the spectacle of her self ‘represented’, projected on a screen, and appropriated from all sides by film-makers and audiences. She feels the same way in her relationship with Gianni: here too she has to keep repeating to herself, ‘Sono io, io.’ Tellingly, he refuses to look at her when she says this. The Clara he relates to is like a recorded performance that runs through a projector in his mind. The connection between this ‘Clara’ and the real person has long since dissolved.

Giuliana, too, is offered endless ‘representations’ of herself by others. The allegedly healthy form of object relations being sold to her requires her to see herself as though from others’ points of view, as someone with a defined relationship to her husband, son, job, or dog, and as someone who loves each of them separately. This would enable her to play a range of discrete roles – wife, mother, ceramicist, dog-owner – which cannot be played all at once. To play them all at once, to blur the lines between them, is to reject the business of role-playing altogether, to reject ‘love’ as she is required to understand it, and to reject the culture she lives in.

When Mario’s wife returns from the kitchen, she tries to discourage Corrado from pursuing this recruitment drive. She would rather keep her husband at home; once, when he went away for a few days, she was terrified (‘I thought I would go mad [credevo di diventar matta].’

To diventar matta because of a lost or interrupted connection with a loved-one clearly mirrors Giuliana’s own experience of ‘going mad’, at least as her doctors interpret her condition. John David Rhodes reads the protests of Mario’s wife in the context of Corrado’s capitalist venture, and weaves this reading into an interpretation of the focus shifts I discussed in Part 16:

In the scene in which Giuliana and Corrado pay a visit to the worker’s flat in the housing estate, the movement – across a single shot – of objects from large to small, background to foreground, focus to out of focus – absorbs our attention as much as any words that pass between the two characters at this moment. Antonioni’s style here functions as a means of distancing and approximation. The nearly too-intimate encounter with the worker’s wife (as this scene develops), who clearly does not want her husband to emigrate for fear of its impact on his mental health, operates as well through an economy of distance and proximity. She would keep her husband close; global capital would draw him far away, to Patagonia. […] [T]he style’s flattening and distancing, its drawing near and pushing away might be said to literalise – at the level and on the surface of the image – the film’s preoccupation with the distortions of near and far that occur under global capitalism. […] Style presents an over-abundance of visual material that is entirely abstract, but that also asks us to read this visual abstraction as the legible sign of the abstraction of economic and social life.5

This also makes me think of the distortions of perspective in Gianni Dova’s ‘flattened’ Rite of Spring (see Part 11), whose prominent place in Giuliana’s home seems like another ‘legible sign of the abstraction of economic and social life.’

Giuliana is like the sacrificed dancer at the centre of that painting, who is robbed of shape, identity, and depth but also placed in a too-intimate relation with the other quasi-human figures to the right and left. Giuliana’s relation to the apartment complex in Ferrara – to the eel that jumps out at her, to the pathway that see-saws under her feet, to the pink flowers that are always behind her and somehow pervasively present in the space she inhabits – is characterised by this play between distance and proximity. (There is also more to say about the colours in Mario’s home, but I will come back to this in Part 19.)

Corrado tells Mario’s wife that she can join him in Patagonia, as though this would be the easiest thing in the world. He, as we have seen, has no firm sense of being anywhere in particular, so of course he does not understand this woman’s anxieties. Richard Letteri, like Rhodes, reads this conflict in terms of the impact of capitalism:

[Giuliana’s] acknowledgement during her conversation with Corrado at the oil rig that Mario, the worker from Ferrara, was in the hospital with her provides us with a larger sense of the ill effects that capitalism deterritorialisation has not only on Giuliana, but on workers like Mario. Likewise, his wife, who [asserts], perhaps in an attempt to cover up her husband’s mental instability, that she would go crazy if Mario left for Patagonia serves to indicate the negative psychological effects the pursuit of capitalist gains would have on many Italians. That Giuliana, Mario, and perhaps his wife, suffer from the same neurotic condition indicates that the ills wrought by capitalist deterritorialisation traverses both gender and class lines.6

Letteri persuasively argues for a connection between these three characters. Something about their sense of identity and belonging, their relation to their local and global contexts, has been altered by schemes like Corrado’s and by industrialisation more generally. What once seemed close is now far away, and vice versa. But to suggest that Giuliana, Mario, and his wife may suffer from ‘the same neurotic condition’ is to flatten out the distinctions between them in a way that Giuliana might find troubling. Does Ugo’s departure, later in Red Desert, affect her in the way Mario’s would affect his wife? When Rhodes and Letteri talk about ‘the distortions of near and far that occur under global capitalism’ and ‘the ills wrought by capitalist deterritorialisation’ I think they are talking about the distortions and ills that put Mario in the clinic, and from which he has recovered by re-negotiating his place within ‘industry’, by being the kind of worker who would immediately turn down Corrado’s offer of international work. We get the impression that Mario and his wife are still in a precarious state – she is rattled by Corrado’s visit; perhaps Mario is too – but they are also presented as a couple who are on the same page when it comes to ‘work’ and ‘home’ in a way that Giuliana and Ugo (or indeed Giuliana and Corrado) definitely are not.

This is not to dismiss the connections highlighted by Rhodes and Letteri, or the idea that Giuliana’s illness has something to do with the effects of capitalism. One of my recurring arguments in this series is that the ‘problem’ in Red Desert is not simply (and perhaps not at all) in Giuliana herself. Her world really is changing, really has changed, at a rapid pace. It really does shift beneath her feet. The people in it are not what they used to be, nor can they even be relied on to remain recognisably human, recognisably distinct from inanimate objects. Vittoria expresses this fear in L’eclisse when she tells a friend about her long drawn-out break-up conversation with Riccardo:

All that time spent talking. And what then? […] What do you want me to tell you… There are days when holding a needle, a piece of cloth, a book, a man…is the same thing.

In that film, the protagonists are replaced in the final seven minutes by similar-looking (or dissimilar-looking) strangers, or by the places and objects they have interacted with, as if they are indeed interchangeable. Things and people are duplicated, replaced, eclipsed, blurred into each other.

In Red Desert, Giuliana lives in this post-eclipse world. If trees can be obliterated by carbon black and factories have replaced forests, how is she supposed to distinguish between them? If the boundaries between people, machines, and objects have also become blurred, how is she supposed to maintain healthy attachments with them? As well as being a response to the proliferation of industrial buildings and processes, Giuliana’s illness is also a manifestation of a more profound sickness, one which Antonioni located in the modern attitude towards love, and I will say more about this in Part 19. For now, it is important to note that Giuliana’s illness entails a rejection of role-playing and self-representation: her frustration echoes Clara Manni’s frustration with the film industry and Vittoria’s frustration with the clichés of romantic break-ups.

The topic of role-playing opens up other ways of thinking about Giuliana’s issues with attachment. Christine Henderson provides an eloquent and carefully delineated diagnosis of Giuliana’s illness, and one which to some extent agrees with the diagnosis offered in the clinic:

Interior and exterior landscapes are inextricably intertwined: this is what endows the forms and contours of the built environment with their menacing and often uncanny quality, and explains why Giuliana encounters them as traumatic and anxiety-provoking. Giuliana is unable to differentiate the two: self and world. She has no clear boundaries, but knows only a state of more or less pronounced continuity, experienced as alarming, even potentially annihilating. […] [H]er moments of isolation are experienced in the manner of a deeply painful, intolerable severance. […] [H]er inability to lose, to accept the constitutional split that is the basis of differentiation, means that she is actually incapable of real love, feeling, desire in a world of particulars, of objects that are separate and distinct from the subject.7

Seen from this point of view, through a Kristevan psychoanalytic lens, Giuliana becomes what the clinic makes of her – a person with a mistaken view of self, others, and the world – who needs to (and, in Henderson’s analysis, eventually does) complete the necessary stages of subject formation in order to be ‘cured’. This may well be the diagnosis and prescription Giuliana and/or Antonioni need, but Red Desert is more exploratory and less optimistic than the film Henderson seems to describe here. It is less interested in tracing the wrong turns in Giuliana’s subject formation, from a clinical or therapeutic perspective, than it is in representing (from Giuliana’s own perspective) her sense of alienation from self, others, and the world.

For example, we might see Visconti’s Bellissima as more conducive to the kind of analysis Henderson is engaged in. Maddalena, the proud mother trying to make a film star out of her daughter, gazes into a mirror and reflects on the nature of acting: ‘After all, what is acting? If I imagined myself to be someone else, if I pretended to be someone else, I’d be acting.’ Then she turns to her daughter, Maria, and combs the child’s hair back from her face (‘like mamma’), just as she combed her own hair in the mirror a few seconds earlier. She holds Maria’s chin as she looks down at her, and for a moment it is as though the child’s face were a hand-mirror, obediently reflecting back the expected image. ‘A mirror, a light, and the room becomes a stage or a set,’ comments Francesco Casetti; ‘What is acting? A synonym for living.’8 As in La signora senza camelie, the ‘performance’ problem dovetails with the ‘relationship’ problem.

Millicent Marcus reads Bellissima’s mother-daughter relationship in the light of Lacan’s theory of the ‘mirror phase’:

Gazing at her reflection in the looking glass, primping and posing to make that image ever more glamorous as she fantasizes about the acting career she never had, Maddalena both recognizes herself yet sees the image as the more accomplished individual she longed to become. Acting, the art of pretending to be someone else, would have let her embrace that ‘better’ self, enabling her to remedy the split between consciousness and image that has left her so frustrated and incomplete. Clinging to this belief, Maddalena has remained in a state of arrested development, caught up in the process of narcissistic identification that keeps her hostage to the imaginary and will not let her progress to a mature recognition of others as autonomous beings with their own distinct consciousness and needs. To get beyond the mirror phase, to transcend infantile narcissism, is to use the process of misrecognition, of perceiving the image to be a better self, as a step on the road to intersubjectivity. […] She cannot acknowledge the link between the ideal image in the mirror and an autonomous other with whom she can some day identify and relate. Thus when she turns from the looking glass to confront Maria with her thwarted dreams, her daughter simply becomes another mirror, a surface onto which Maddalena will displace her frustrated desire to embrace an ego ideal through acting.9

Sure enough, at the climax of the film, Maddalena snaps out of her deluded and unhealthy fixation on her daughter’s acting career, in what Marcus calls a ‘psychocinematic pun, where the technological and emotional meanings of projection come together to expose the abuses of cinematic enchantment.’10 Maria’s traumatic audition is projected on the screen and Maddalena watches from the projection booth. The child, held in her mother’s arms, watches the film as well, but after a minute Maddalena covers Maria’s eyes to protect her from this awful spectacle.

Afterwards, when the studio offers Maria a part in a film, Maddalena furiously rejects this opportunity:

[She] reveals her acceptance of the child as other, come tutte le altre [like all the others], and thereby signals her passage, beyond the looking glass, to the other side, or to put it more appropriately, to the side of the other, where reflection gives way to relation and daughters can become autonomous selves.11

Bellissima is a complex film in many ways, but on one level it functions as a cautionary tale with a happy ending, in which the protagonist learns to relate more healthily to her own image in the mirror and to the daughter she has been projecting onto. Maddalena, though wonderfully three-dimensional, is also eminently diagnosable and curable.

When it comes to looking in mirrors and relating to others, I think Antonioni is more in tune with Cesare Pavese’s Among Women Only, the novel on which Le amiche is based. In the following passage, the narrator, Clelia, is talking with her new friends Momina and Rosetta. The conversation is about Rosetta’s recent suicide attempt, what she was thinking about at the time, and whether she looked in the mirror before doing it (she says she didn’t). Clelia tells an anecdote:

‘I knew a cashier in Rome,’ I said, ‘who went crazy from seeing herself all the time in the mirror behind the bar [a forza di vedersi allo specchio, lo specchio dietro il banco, diventò pazza]… She got to thinking she was somebody else [Credeva di essere un’ altra].’

Momina said, ‘One should look at oneself in the mirror… You’ve never had the courage, Rosetta…’

We talked on like that, about mirrors and the eyes of a person killing himself [dello specchio e degli occhi di chi si uccide].12

Note the repetition of specchio in the first paragraph, which is left out of Paige’s translation: ‘from seeing herself in the mirror, the mirror behind the bar…’ In the final paragraph, the singular form of specchio is hard to translate elegantly, so Paige converts this to the plural ‘mirrors’, but Clelia is thinking of ‘the mirror’ as a concept. In her anecdote she has to repeat the word in order to clarify that she is referring to a specific mirror – the one this unfortunate cashier had to stare at all day long – but this conversation is really about Rosetta’s relationship (i.e. the suicidal person’s relationship) with ‘the mirror’ as such.

The next day, Rosetta confides in Clelia:

‘I’d like to be someone else [Vorrei essere un’altra], like that cashier in Rome. Even crazy like her.’13

Towards the end of the novel, Momina refutes the idea that Rosetta is unhappy because of a thwarted lesbian relationship between them. The problem, Momina says, is deeper than that:

‘I don’t like women, and neither does Rosetta. […] It’s an idea Rosetta’s got into her head. It happened three years ago […] She came into a room and found me… I wasn’t alone [Non ero sola]. […] Then she wanted to be daring, but the impression stuck and she considers me… something… her reflection in a mirror [mi considera… qualcosa… come il suo specchio].’14

Again, the translation (understandably) dilutes Pavese’s reference to the specchio. Rosetta does not consider Momina her ‘reflection in a mirror,’ she considers Momina ‘her mirror’ as such. The word qualcosa, drifting between ellipses, captures the elusive nature of Momina’s insight into her friend’s illness. As with Giuliana, it is reductive to see Rosetta as suffering from a ‘love problem’, here figured in terms of unrequited or transgressive love. It is, according to Rosetta, also reductive to see her as ‘mad’ – she wishes she were mad, like the cashier who ended up thinking she was someone else. Rosetta cannot look in the mirror because Momina is that mirror, and unlike in Le amiche there is little sense that Momina is a toxic, abusive friend who is somehow responsible for Rosetta’s death. The ‘something’ that Momina stands for in Rosetta’s mind is inexpressible, it mirrors something that cannot be seen in itself or by reflection. Among Women Only attempts to portray that thing, to make us feel it, without its being shown or verbalised.

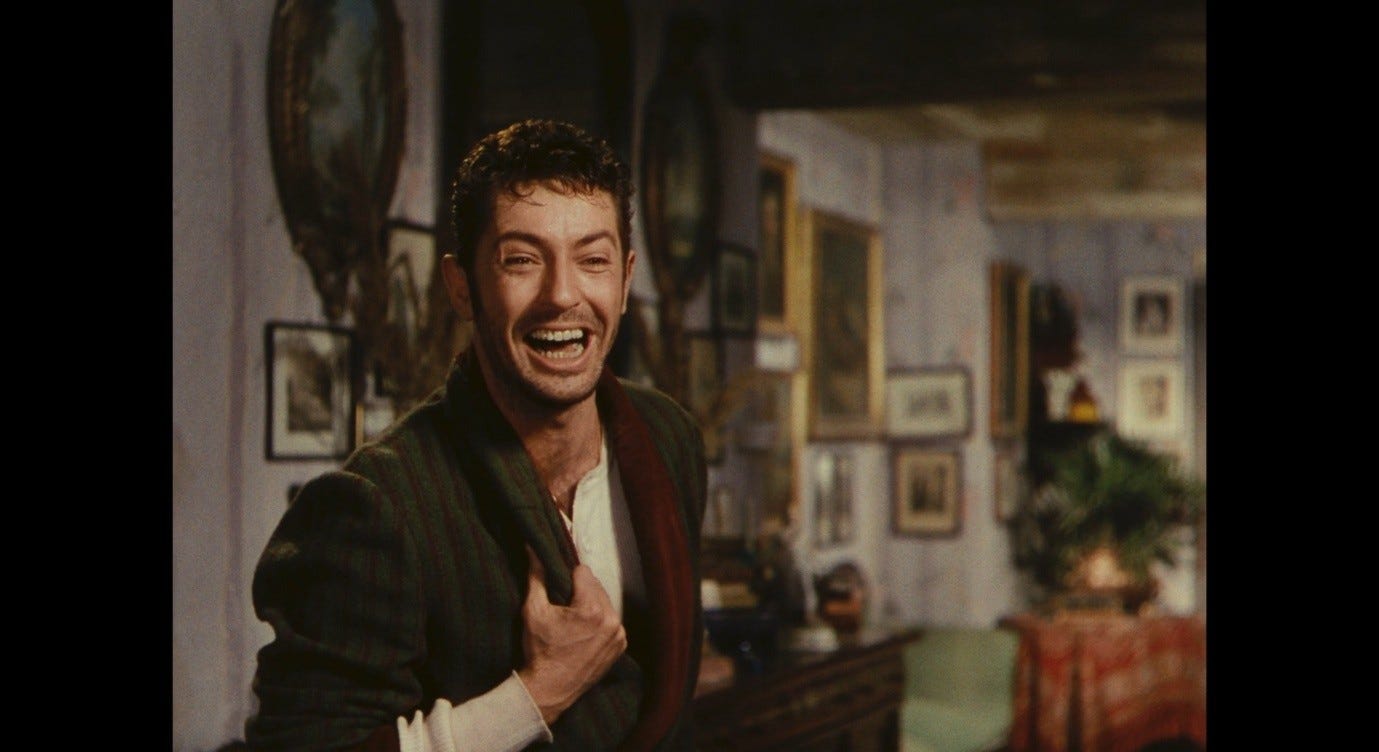

For me, what is evoked in Pavese’s novel is weirdly similar to what Visconti evokes in Senso, which also plays with mirrors, selves, and ‘others’ in a way that is not easily framed as a psychoanalytic cautionary tale. Franz, the preening lieutenant, says that he never passes a mirror without looking at his reflection, ‘to be sure that I am me [per essere sicuro che sono io].’ He and Livia are sitting beside a deep, dark well, a murky abyss that might also ‘reflect’ something of Franz’s character - he tosses the mirror fragment into it.

‘To be that which I am [Per essere quello che sono],’ he says when Livia asks what he was ‘born for,’ and at the climax of the film he exposes his true nature to her: ‘Who am I [Chi sono io]?’ he asks rhetorically, before revealing what a treacherous scoundrel he is. ‘Tell me, who do you think you are [chi ti credi di essere]?’ he asks Livia, as though making himself into her mirror: this is an act of mutually assured destruction on his part, meant to induce a state of total self-knowledge, self-loathing, and self-annihilation in both himself and her. A reverse-shot of Livia shows her looking at Franz, and at the camera (at us) so we can identify with her, and we feel the full intensity of her despair as she lets out a guttural scream. Franz’s grin is like the Babadook’s – a howl that looks like a laugh – and Livia mirrors it back at him.

In Part 20, I will talk about Alida Valli’s scream at the end of Il grido, which is harrowing but noticeably transient – it is a grido (a cry) that dissipates within a moment. Valli’s scream in Senso is supposed to haunt us for a long time after the film has ended, because it represents that confrontation with reality, that look-in-the-mirror, that Rosetta (according to Momina) did not have the courage for. Angela Dalle Vacche, referring to the mirror-fragment scene in Senso, argues that ‘Livia does not have the gift of self-knowledge,’ and that at the film’s climax she ‘acquires a pathological identity as soon as she cannot be the female alter-ego of any male character.’15 Indeed, her madness and her status as an alter-ego are intertwined, and are intertwined with Franz’s own pathology and alienation from himself. Paradoxically, his awareness of that alienation is the form his ‘self-knowledge’ takes. Franz’s seeming narcissism as he looked into that mirror-fragment was just a cover for the deep well of self-hatred that he shows Livia at the end of the film. Perhaps part of him, like Rosetta, wanted to love someone per essere un’altra, to be otherwise than he was through attachment to another. Instead, he is driven not only to essere quello che sono, but to drag Livia into that dark well and make her like him, to make her ‘what he is.’

Clara Manni’s defiant but tormented cry of ‘Sono io, io’ resonates through all of these stories: that insistence on one’s own identity, mixed with a horror at the role one finds oneself trapped in, hopelessly externalised and just as hopelessly internalised. In Red Desert, it is in the hope of imposing a kind of role on someone that Corrado travels to Medicina, and in this case the role is emphatically rejected (to Giuliana’s delight). However, the key emotional beat in the Medicina sequence is the encounter between Giuliana and Mario, which distinguishes his stability and self-assurance from her intense vulnerability. Mario does not even recognise Giuliana until she greets him. This echoes her alienation from the factory workers at the start of the film. It would not occur to Mario that he might have a personal connection with this well-dressed woman visiting his construction site (note how he glances at her coat when he walks past).

When they do speak to each other, Mario is filmed from behind or from a distance, his face obscure and his tone of voice neutral.

To Giuliana’s earnest enquiry about his health, he replies politely that he is well. When he turns the question back on her, she is just as polite: ‘I too am very well, thank you [Anch’io, molto bene, grazie].’

As mentioned above, it will turn out that Giuliana and Mario were both patients in the clinic. In this man’s home, in his absence, and speaking to her own spectral alter-ego on his sofa, Giuliana has just been telling her story through the medium of a fictional ‘other patient’. Now she encounters a real-life other patient whose illness, we are left to presume, resembled her own in some way. The woman in the clinic was cured but Giuliana was not; Mario seems to have been cured as well, to the point that he no longer recognises his fellow patient, leaving Giuliana feeling yet more isolated.

When they speak to each other, he is not given a close-up but she is. If the exchange had been filmed as a typical shot/reverse-shot, we might see the close-up of Giuliana as representing Mario’s point of view. Without the corresponding close-up of Mario, we are shut out from his perspective and thereby made to feel that he does not see Giuliana: not only did he not recognise her at first glance, but in his cured state he can no longer really ‘see’ her at all. We see her, though, and intimately enough to be able to track the progress of her facial expressions. There is a pause as she takes in the news of his recovery, with a hint of sadness and disappointment, her eyes flickering slightly as she looks him up and down.

There is an exaggerated series of little nods and the attempt at a smile as she says she is very well.

Her whole face falls as she says ‘grazie,’ her eyes looking down as though she cannot bear to keep looking at this man.

Then she quickly looks back up and gives her characteristic wry smile.

She gives a series of looks (down, up, and to the side) as she resets her brain and directs Mario towards Corrado.

And finally there is the steady, friendly gaze to make sure that she leaves the conversation on a positive note.

Throughout this remarkable shot, Giuliana is framed against the red girders of the observatory’s antennae. We have seen these antennae from a distance, as identical mass-produced technological wonders stretching into infinity.

We have also seen them close-up, from perspectives that make it seem as though the camera has been incorporated into the antennae.

As in Ugo’s factory, there is a sense that the machines have a life of their own and that they are watching the humans who walk among them. But in this famous medium close-up of Giuliana, the antennae have become abstract shapes.

Arranged in a series of large criss-crossing lines, with each line containing a web of smaller criss-crossing lines, the antennae resemble a network of veins and capillaries. They also resemble an image in T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’:

It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen:

Would it have been worth while

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

‘That is not it at all,

That is not what I meant, at all.’16

These lines articulate the difficulty of self-expression, the fear of misunderstanding and being misunderstood. For a moment, we imagine that a person’s feelings – their entire nervous system – could be represented externally for all to see, and that it would appear ‘in patterns’, in a form that would make sense. Could a person finally make themselves understood in this way? Or would such a vulnerable act of self-exhibition result in misunderstanding and social embarrassment (‘That is not what I meant, at all’)? What Giuliana feels is not the same as what Mario feels; what she ‘means’ is not legible, and it would clash with Mario’s ‘meaning’; so it is better to just say ‘Very well, thank you.’

Giuliana’s nerves are projected on the cinema-screen we are watching, but they remain in the background and out of focus, belying (for us) her performance of wellness and remaining unseen by Mario. As well as representing something in Giuliana, they also represent something external to her. These are the blood vessels of the quasi-sentient machines that loom menacingly behind her, just as the fire-spouting flare stack did at the start of the film. Murray Pomerance makes a convincing case for these antennae as constituting a manifestation of the ‘red desert’, though his reading of the encounter with Mario differs from mine:

The red towers say nothing, hear nothing. They form an antenna for ‘listening to the stars.’ Given that they beckon meaning, but offer none, they constitute a kind of ‘desert,’ a vast and empty, but magnificent, potentiality. It is in this ‘desert’ setting, a place purified of all bias, that we see Giuliana, briefly, in conversation with the worker and recognize that they share something deep and personal.17

Perhaps, contrary to what I said above, this shot of Giuliana’s fluctuating expressions is supposed to create a sense that this moment between her and Mario is profound and intimate. In Pomerance’s reading, this encounter is a fulfilment of what Clara wished for in the desert space where she took Nardo (see Part 12): a place of potentiality, without bias, that can facilitate meaning without imposing it. But when I watch Giuliana’s reaction to Mario’s gaze, I see something like Clara’s dismay in the face of Nardo’s incomprehension – that ‘instead…’ that trails off in despair of being able to say what has not been comprehended (‘It is impossible to say just what I mean!’).

Matthew Gandy’s reading of the film’s use of colour and long lenses is enlightening here, especially in the way it overlaps with Rhodes’ point about shifts in focus:

The deliberate artificiality of colour in Red Desert mimics the technological artifice of the industrial landscape and also emphasizes the complexities of colour perception. […] The repeated use of a narrow focal range, for example, enables Antonioni to emphasize very specific elements in the frame, such as a human face or the surface of a wall. In so doing, our attention is shifted between different elements in the landscape and there is a clear break with any attempt to emulate cinematic realism in its narrow sense.18

The scene in Medicina illustrates this even more clearly than the one in Ferrara, dramatically shifting our attention between disparate objects, isolating Giuliana against them, and confronting us with the artificiality of colour – we can see that not all the girders have been painted red yet – to make this scene feel as non-realistic as possible.

When we see Giuliana against the red girders, we seem to be inside the world conjured by Prufrock’s magic lantern. Those are not antennae but exposed nerves, and this is not a dialogue between two people but a moment of inexpressible angst (‘something…her mirror…’) in the mind of one person. Antonioni said he chose the image of a desert ‘because there are few oases left’ and the colour red ‘because it’s blood. The living, bleeding desert, full of the flesh of men.’19 Something about the observatory and her encounter with Mario makes Giuliana sense the living, bleeding desert all around her. Antonioni’s description of this desert connotes a ‘left behind’ feeling: the oases have been destroyed and the desert is left behind; the flesh that constitutes that desert is still living and bleeding, though it appears to be as dead and white as Zabriskie Point.

Antonioni filmed this scene at the Medicina Radio Observatory, at a time when it was still under construction (according to the History page on the observatory’s website). The workers carrying metal pipes and climbing precariously inside the antennae make us aware of the human labour required to build these impressive structures.

A black house, pointedly emphasised in the opening shots of this sequence, re-appears in the background throughout (not unlike the pink flowers in the previous scene). Although the house is far away from the carbon-black deserts generated by the factories, its blackness makes it seem like a charred, abandoned ruin when juxtaposed with the gleaming red antennae that dominate the landscape like scorpions’ tails. Giuliana seems fascinated by the house, pausing to stare at it when she arrives.

Moments later, she is just as fascinated by the antennae. The contrast between the two types of structure clearly resonates with her condition and with the contrast between her and Mario. The house seems poignantly archaic, isolated, depressed, and uninhabited; the antennae are as modern as could be, and even from a distance we can see they are crawling with people. The house is grounded in the earth, visually associated with the long yellow grass in the foreground and the bare, lightly reddened tree nearby. The antennae reach into the sky and are designed to capture the sounds of the stars (rumori delle stelle). ‘Can I listen too?’ asks Giuliana. The worker, deftly moving among the girders high above, replies that she would need to climb up to his level, which of course she is too scared to do – she cannot comprehend the worker’s fearlessness.

It is not literally true that Giuliana would have to climb into the antenna to hear the cosmic sounds being received, but the joke underlines how inaccessible this place is for her. These rumori delle stelle are as inaccessible as those produced by the intonarumori of Luigi Russolo, or the other kinds of futurist music discussed in Parts 3 and 4. The encounter at Medicina is yet another de-stabilising, boundary-breaking event in Giuliana’s world, blurring the definition of the world itself by connecting it with (potentially) the entire universe. Mario, like a pod person (or ultracorpo) in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, ‘reborn into an untroubled world,’ has joined the rest of the human race in making peace with these new developments. Giuliana is left behind. The final image of the sequence reiterates the juxtaposition of red girders and abandoned house, both out of focus and abstracted behind Giuliana. They remain on screen for a few seconds of dead time after she has left.

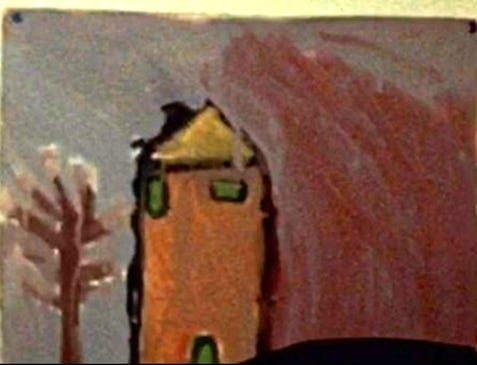

There is perhaps a subliminal association with Valerio’s painting of the isolated house and smoke-covered tree about to be overrun by a wave-like red shape.

In both these images, we see Giuliana’s territory – home, self, io – threatened by an encroaching force, but we also share her sense that for everyone else the images are innocuous; a child’s painting, a landscape under renewal. This tension between Giuliana’s perspective and those of the people around her will come to a head in the next sequence, when she has to navigate a complex social encounter in another kind of red desert.

Next: Part 18, The daytrip gone wrong.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), pp. 196-197

Luzzi, Joseph, ‘Red Desert (Il deserto rosso) (review)’, Modernism/Modernity (18.1, 2011), pp. 205-209; p. 207

Luzzi, Joseph, ‘Red Desert (Il deserto rosso) (review)’, Modernism/Modernity (18.1, 2011), pp. 205-209; p. 207

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 451

Rhodes, John David, ‘Antonioni and The Development of Style’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 276-300; pp. 292-293

Letteri, Richard, ‘Becoming Giuliana: Antonioni’s Red Desert and the Capitalist Social Machine’, Deleuze and Guattari Studies 15.1 (2021), pp. 91-116; p. 99

Henderson, Christine, ‘The Trials of Individuation in Late Modernity: Exploring Subject Formation in Antonioni’s Red Desert’, Film-Philosophy 15 (2011), pp. 161-178; pp. 163, 167

Casetti, Francesco, ‘Cinema in the cinema in Italian films of the fifties: Bellissima and La signora senza camelie’, Screen 33.4 (Winter 1992), pp. 375–393; p. 384

Marcus, Millicent, After Fellini: National Cinema in the Postmodern Age (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), pp. 55-56

Marcus, Millicent, After Fellini: National Cinema in the Postmodern Age (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), p. 56

Marcus, Millicent, After Fellini: National Cinema in the Postmodern Age (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), p. 57

Pavese, Cesare, Among Women Only (1949), trans. D. D. Paige (London: Peter Owen, 1953), p. 92. Italian text from Pavese, Cesare, Tra donne sole (Torino: Einaudi, 1998), p. 91.

Pavese, Cesare, Among Women Only (1949), trans. D. D. Paige (London: Peter Owen, 1953), p. 93. Italian text from Pavese, Cesare, Tra donne sole (Torino: Einaudi, 1998), p. 92.

Pavese, Cesare, Among Women Only (1949), trans. D. D. Paige (London: Peter Owen, 1953), pp. 115-116. Italian text from Pavese, Cesare, Tra donne sole (Torino: Einaudi, 1998), p. 116.

Dalle Vacche, Angela, The Body in the Mirror: Shapes of History in Italian Cinema (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 139, 153

Eliot, T.S., ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, in The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot (London: Faber, 2011), pp. 13-16; p. 16

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 97

Gandy, Matthew, ‘Landscapes of deliquescence in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, 28.2 (2003), pp. 218-237; p. 227