Everything That Happens in Red Desert (22)

How to see and how to live

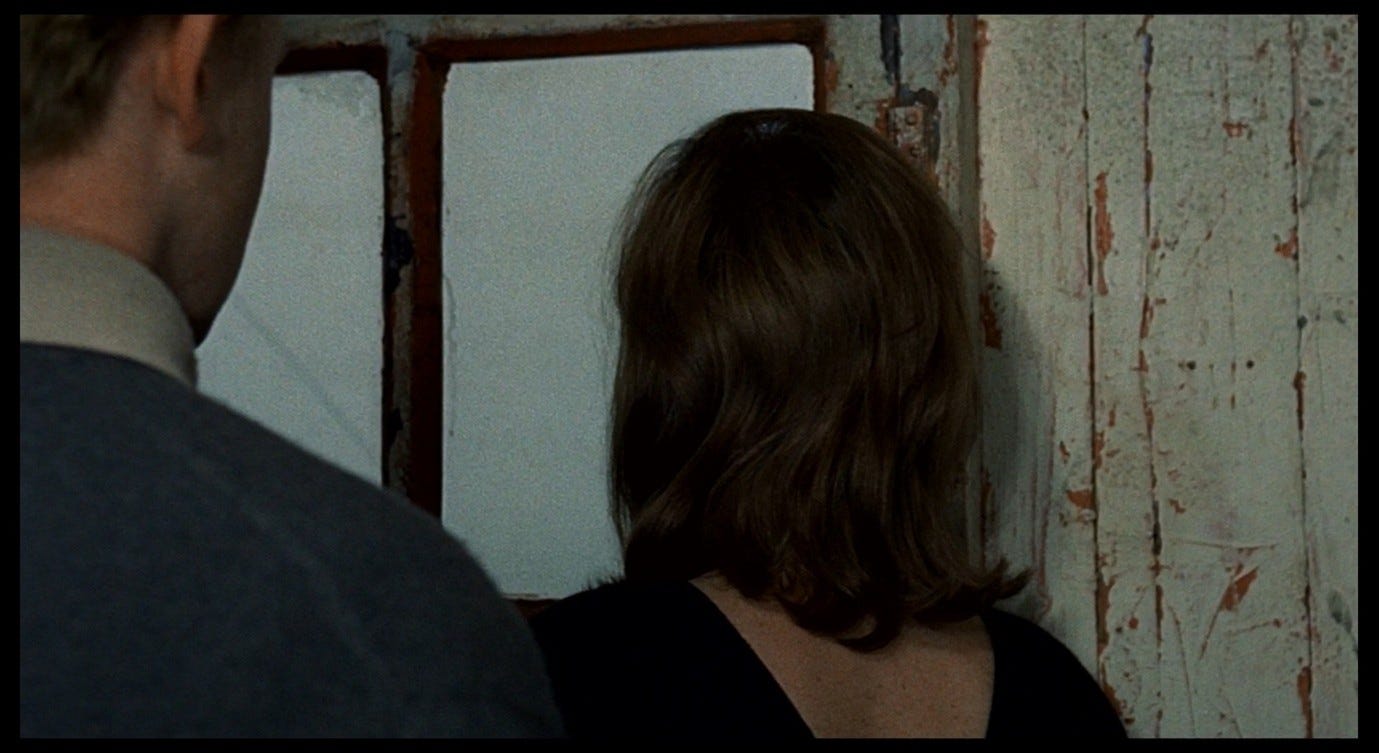

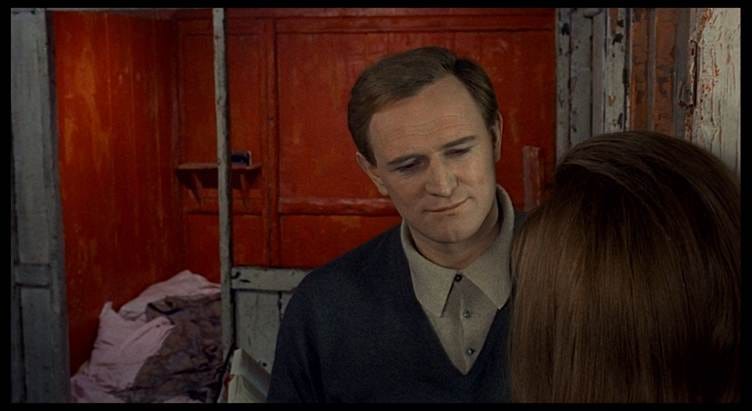

The ever-changing world around Giuliana constantly intrudes upon her experience of life, pulling the ground from beneath her feet. For Corrado, this is a desirable mode of existence – to be incessantly changing places, changing contexts, and renewing himself through a new ambiente. The tensions between Giuliana’s and Corrado’s sense of self and response to change are revealed in their conversation near the end of the daytrip sequence. They have just been tearing the shack apart to feed the stove, and the melancholy aftermath of that episode has just swept over them. Giuliana looks out of the window at the sea and says:

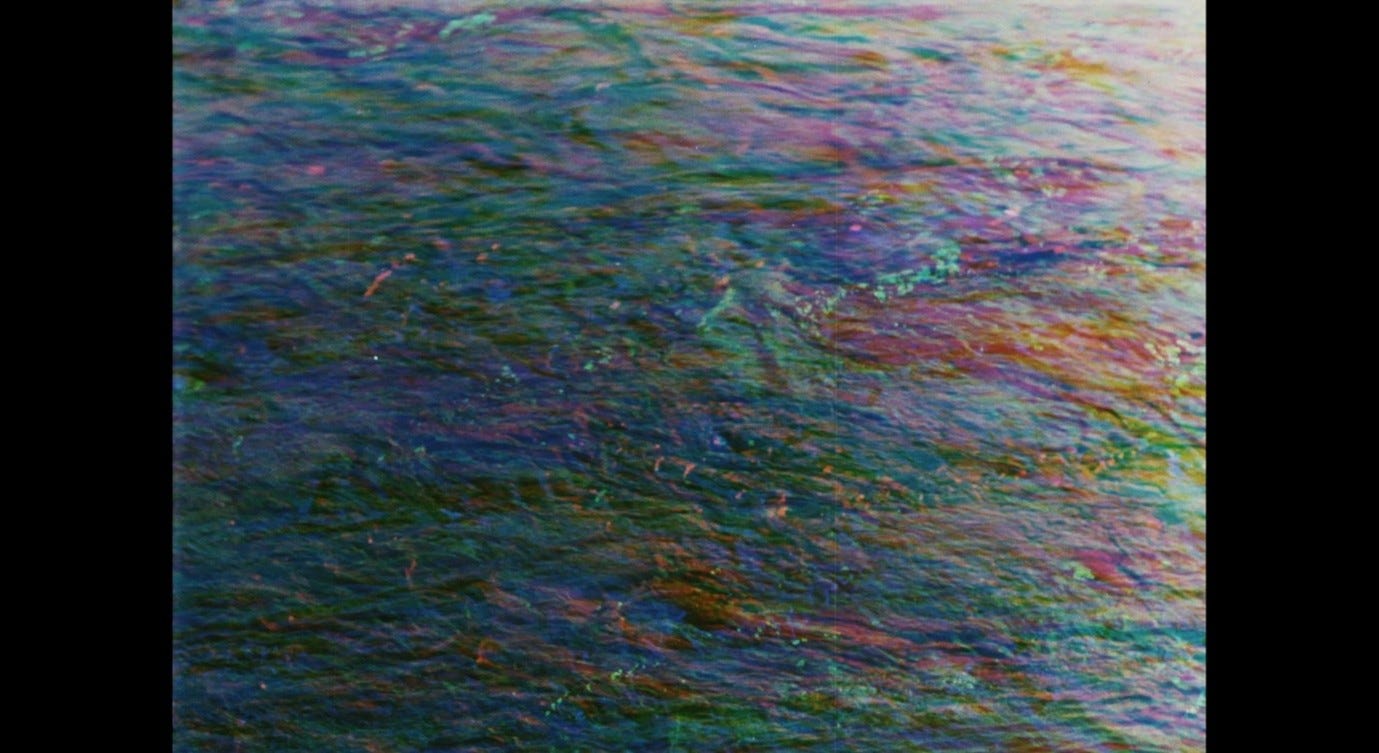

It never stays still, never, never [mai, mai]. I can’t look for too long at the sea, or I lose interest in what’s happening on land.

Giuliana’s plaintive comment turns out, as we discover in the reverse-shot, to be addressed to Corrado. After a moment’s hesitation he responds:

I sometimes wonder if it isn’t futile – how seriously one takes a job I mean. Doesn’t it seem [sembra] ridiculous to you?

She picks up on the word sembra but does not answer his question:

It seems [sembra] to me that my eyes are wet [bagnati]. But what do they want me to do with my eyes? What should I look at?

Corrado replies:

You say: ‘What should I look at?’ I say: ‘How should I live?’ It’s the same thing.

There is, in some sense, a real dialogue between these two people – they are ‘comparing notes’ in a meaningful way, which is more than Giuliana gets with anyone else – but the comparison repeatedly shows up the extent to which they inhabit different worlds. Giuliana is afraid of losing interest in the land. This un-grounded state is precisely what Corrado seeks out, what keeps him going. For Giuliana, looking at the sea makes her eyes feel ‘bathed,’ infected with the properties of the sea and rendered changeable, unable to rest. Her repetition of ‘never, never’ anticipates her later cry of despair (to Corrado) when she says ‘I will never be cured, never, never, never...’ The transience – or ‘progress’ – that enables Corrado to move easily from one job, one mindset, one relationship to the next, makes Giuliana incurably unwell. Her earnest soul-bearing clashes with Corrado’s ‘maybe jobs are bullshit’ flippancy. His work ‘seems’ ridiculous to him; her eyes ‘seem’ to be seeping out of her head. She is frantic when she asks what she should look at; he responds by complacently equating her question with his own, smiling at her with an air of dismissive reassurance as he says, ‘it’s the same thing.’ ‘Yet, he’s wrong: it’s not at all the same,’ says Murray Pomerance:

For Corrado, how to live means where to go, what to buy, what to make, who to employ – it’s all progress. For Giuliana, what to look at means where to stand, how to make boundaries, how to arrange surfaces, how to lose interest in the land when one gazes at the sea.1

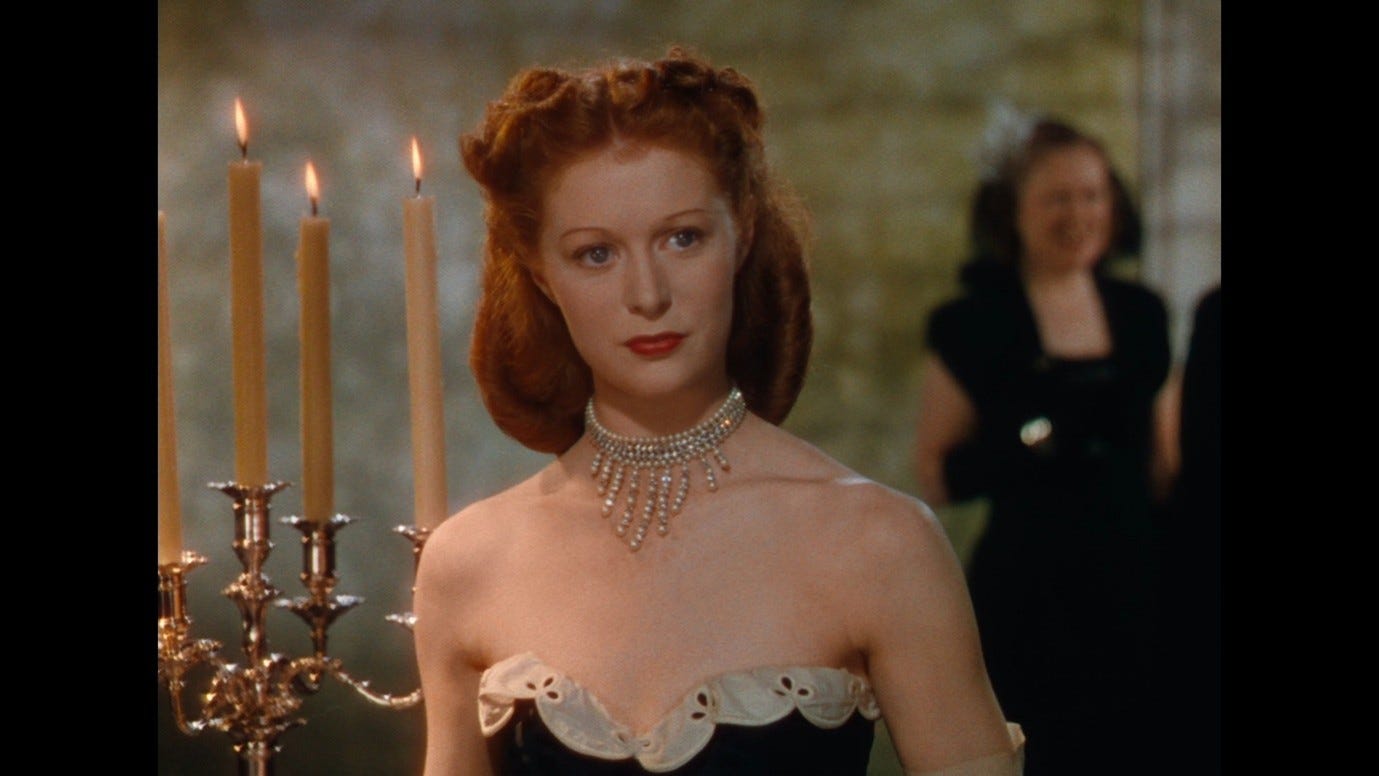

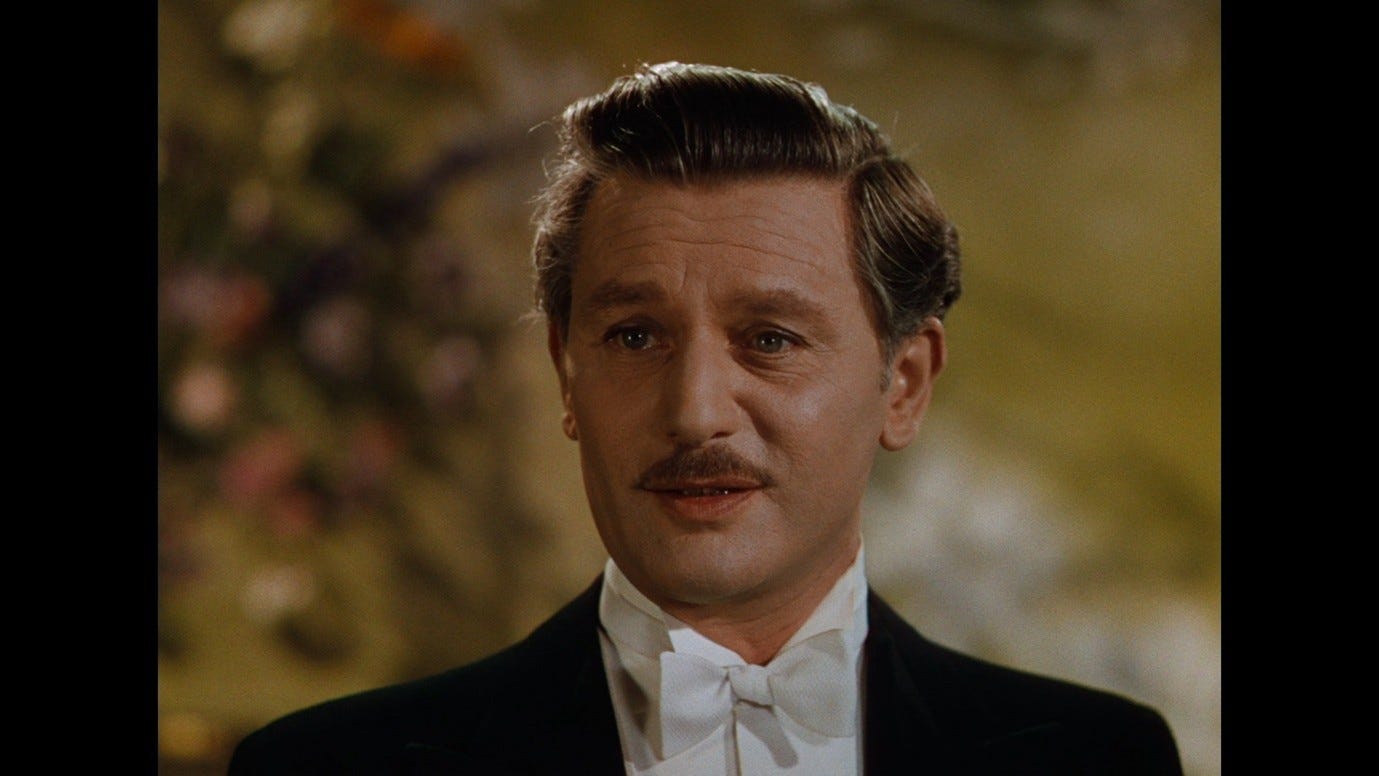

The way Pomerance phrases this clarifies something about the difference between the two characters. Corrado’s actions are not only about progress but also change: going somewhere else, acquiring new things, filling empty spaces with industrial edifices, assigning people to new roles. Giuliana’s actions, as Pomerance describes them, sound like those of a film-maker: where to position the camera, how to compose a shot, how to decorate a set, and how to make this film-world more absorbing than real life. ‘Giuliana’s questions,’ says Eugenia Paulicelli, ‘are similar to those of visual artists who might ask themselves how the canvas, and the frame, can contain what one feels and sees.’2 To the canvas and the frame we might add the ballet stage. In The Red Shoes, when the impresario Lermontov first meets the aspiring ballerina Vicky, he asks her, ‘Why do you want to dance?’

She thinks for a moment, then retorts, ‘Why do you want to live?’

‘I don’t know exactly why,’ says Lermontov, taken aback, ‘but I must.’ His expressions remind me of Corrado’s.

‘That’s my answer too,’ says Vicky. The conversation is alluded to later when the two characters discuss their shared devotion to their art, their sense that art is ‘more, much more’ than mere living. These questions are central to Powell and Pressburger’s film: can a person define their life in terms of art, or are life and art in conflict with each other? Do life and art hold each other back and does Vicky have to choose between them?

In the central ballet sequence of The Red Shoes, there is a parallel between the girl who cannot stop dancing, who is driven into solitude and death, and Vicky, whose art conflicts with her marriage and who is ultimately driven to suicide by this conflict. In Part 12 we looked at the moment in the Red Shoes ballet when Vicky dances with a newspaper that briefly transforms into a man, and I noted the parallel with Giuliana encountering the newspaper in the Via Alighieri. I suggested that Vicky’s lonely, imaginary interaction with a person who is not there – a paper-thin illusion – was comparable to the love affair in Red Desert. There is perhaps another parallel to be drawn between Vicky’s hallucinatory vision of a raging ocean, consuming the stage beneath her, and Giuliana’s fear of absorption as she stares at the sea.

If The Red Shoes pits life and art against each other and prompts us to consider whether Lermontov’s and Vicky’s questions really are the same, the exchange in Red Desert does something similar. Here the tension is between life and looking, which is significant given that looking is the core component of ‘art’ as Antonioni practises it – the title of his penultimate film literally means The look [sguardo] of Michelangelo. In a 1978 interview, Antonioni foregrounded the importance of looking and creating things to be looked at, while distancing himself from intellectual and philosophical discourse:

I have never been a man of learning who interpreted everything through culture. My way of seeing is in the eye, I believe in the force of the image, of its internal rhythm.3

In the preface to his published screenplays, he said:

[N]obody, more than us filmmakers, is inclined to look. Here is an occupation that I never get tired of: looking. I like almost all of what I see: landscapes, characters, situations. On the one hand, it is dangerous, but on the other, it is an advantage, because it allows for a complete fusion between life and work, between reality (or unreality) and cinema.4

He calls it ‘dangerous’ to be too absorbed in looking at the world, recalling Giuliana’s fear of looking for too long at the sea and being infected by it. But he nonetheless embraces this occupation precisely for the thing that makes it dangerous: like Lermontov in The Red Shoes, he seeks to fuse life and art, to dissolve the one in the other, to the point where (as in the Red Shoes ballet) it is not even clear whether art is capturing reality or unreality.

Giuliana is like Vicky, the ill-fated red-haired muse through whom Lermontov generates art. Red Desert is the artefact that results from the ‘fusion of life and work’ that Antonioni describes. It is like seeing this ‘dangerous’ way of looking translated into a film, with the same breakdown between reality and fantasy that we saw in The Red Shoes. Just as Lermontov needs the ballerina to bring his artistic vision to life, so Antonioni (problematically) needs female characters like Giuliana as vehicles for communicating his sguardo:

Women provide a much more subtle and uneasy filtering of reality than men do and they are much more capable of making sacrifices and feeling love. While living around women, I have often had moments of complete exasperation, and I have felt locked in, suffocated, with a strong urge to escape. And sometimes I did leave. The truth is that I still like women very much.5

Giuliana in Red Desert is a subtle, uneasy, uncomfortably emotive ‘filter of reality,’ exasperating to the other characters in the film and no doubt to many viewers, perhaps including Antonioni himself. If we follow her journey with a sense of empathy, we will feel locked in and suffocated as she does, and may be relieved to escape in the end. In the comments quoted above, Antonioni comes across as someone who has acknowledged the dangers of engaging with the world in a certain way, and who sees the abyss of extreme emotions he might fall into, but who subsumes these emotions into the artistic process and displaces them onto a feminine ‘filter of reality.’ This is, as he implies, a kind of ‘sacrifice’ on the part of this feminine filter. Like Niccolò in Identification of a Woman, Antonioni relates to women as though doing so were a stressful but rewarding artistic endeavour, one that will both excite and upset him (and possibly damage the women in question), but from which he will ultimately remain detached.

We see something like this dynamic in the relationship between Giuliana and Corrado, especially in Max’s shack. She experiences reality without any filter – for Antonioni, the female protagonist is the filter – and is traumatised both by the sensory overload and the insight she gains from seeing the world with such lucidity. This is devastating and debilitating for her, making it hard for her to function in the world, hard for her gears to mesh. Ugo and others are, to varying degrees, fed up with her. But – she protests – what do they expect her to do? Reality happens to her, it surrounds and imprisons her, and she has to react in some way. The question ‘what should I look at?’ conveys this sense of passivity and reactivity. If you are in the middle of the sea, or a cloud of fog, you have no choice but to look at it. An environment you did not create surrounds you and you cannot help but be affected by it. Giuliana’s point is that she is not trying, or choosing, to be disintegrated by the world she lives in. It is just what happens to her.

At the end of the film, Giuliana will reach an uneasy resolution by saying, ‘everything that happens to me is my life,’ and by doing her best to avoid the more poisonous aspects of her environment. Corrado comes at this from the other direction. For him, Giuliana’s question (‘what should I look at?’) is the same as his (‘how should I live?’) because the answer to his question is ‘by looking.’ Besides the interesting parallels between Italo Calvino’s The Watcher and Red Desert (discussed in Part 21), the mere presence of a book about a scrutatore (a ‘watcher’) on Corrado’s bedside table illuminates his role in the film. Giuliana is a victim of the world but (by the same token) deeply engaged with it, like a film-maker compulsively driven to capture something in their ‘reality,’ some aspect of their environment that affects them. Corrado watches – a position seemingly invested with more agency – but keeps his distance. He also resembles a film-maker in that he treats the world and the people in it as objects to be looked at, explored, exploited, and then discarded. Throughout the film, he is clearly fascinated by Giuliana, eager to connect with the experiences and emotions of this intense ‘filter of reality.’ But he is a tourist in her life. He will look at her more openly and attentively than anyone else does, and will come to understand her better, but he will not help her. Ultimately, the truth of her experience will remain beyond his grasp. It is not hard to see the appeal of Antonioni’s approach to art: he gets to see and feel vicariously through Giuliana, but he also gets to live and function more-or-less normally, like Corrado.

The ‘how to see’ / ‘how to live’ exchange takes on an even richer set of meanings when we situate it in relation to the immediately preceding action (the tearing up of the shack) and what comes after it (the infected ship and the vision in the fog). Both of those episodes have some bearing on Giuliana’s and Corrado’s questions. Tearing away the outer planks of the red room means exposing and perhaps subverting that room and its purpose. In the first establishing shot of the shack interior, that room was a glaring fragment of red hemmed in by more muted colours, like a secret no one was ready to acknowledge.

After the hilarity of feeding the stove, it has become a gaping red maw that makes everyone feel ashamed.

How the room looks and what people do in it are inextricably linked. When the characters become shrouded in fog, this effects a different kind of change in the looked-at environment. It becomes difficult to see anyone or anything, and somehow the fact of their invisibility seems linked to the fact of their stillness.

Consider Antonioni’s description of the incident that inspired L’eclisse:

I am in Florence, to see and film a solar eclipse. Unexpected and intense cold. Silence different from all other silences. Wan light [Luce terrea], different from all other lights. And then darkness. Total stillness. All I’m capable of thinking is that during an eclipse even feelings probably come to a halt.6

An alteration in the look of reality – a change in lighting – brings about a unique kind of silence, and then even the light itself seems to change substance. The word terrea literally means ‘earthen,’ and elsewhere Antonioni referred to the eclipse-light as ‘ashen [cinerea].’7 These are the effects he tries to evoke through the grey street and the cloud of fog in Red Desert. Corrado may after all be right about ‘how to see’ and ‘how to live’ being the same thing: every aspect of how we experience life is affected by the way things are lit, coloured, focused, or framed.

The anarchic revelry in Max’s shack – when a place built in a certain way to prompt certain behaviours is deconstructed and subverted – finds a more joyful analogue in the climax of Jacques Tati’s PlayTime, when the pretentious restaurant is deconstructed. Like Max’s shack, the restaurant is in a fragile state, not because it is dilapidated but for the opposite reason: it is not quite finished and not quite ready to open for business. All the over-determined ways in which the restaurant staff try to create a high-class dining experience are gradually foiled by disintegrations – broken floor tiles, over-seasoned food, torn or defaced clothing – which are more conducive to ‘play’ and genuine enjoyment. Monsieur Hulot and some of the other patrons eventually make a home for themselves in a corner of the restaurant, fenced off with pieces of broken décor, in which a spirit of hedonistic freedom reigns supreme.

A little like in Red Desert, Tati’s revelry is followed by the onset of melancholy, as the characters dissipate into the alienating traffic jams of the modern world. However, there is an irrepressible hilarity still lurking within this traffic jam and the cold modern buildings that surround it, in contrast to the more absolute depression that descends (with the fog) in Red Desert.

PlayTime is famously concerned with the question of ‘how to see,’ in that it gives the audience too many things – too many jokes – to notice at any one moment. The climactic restaurant-within-a-restaurant, the pocket of fun tucked away in the margin of a larger space, brings to the fore a motif that runs through the whole film. This is a question of how to live as well, not just for the characters but for the viewer. A film is something you look at but it is also two hours’ worth of your life, and in this case your choices regarding how you look at the film will radically affect how you experience it – how much fun you have.

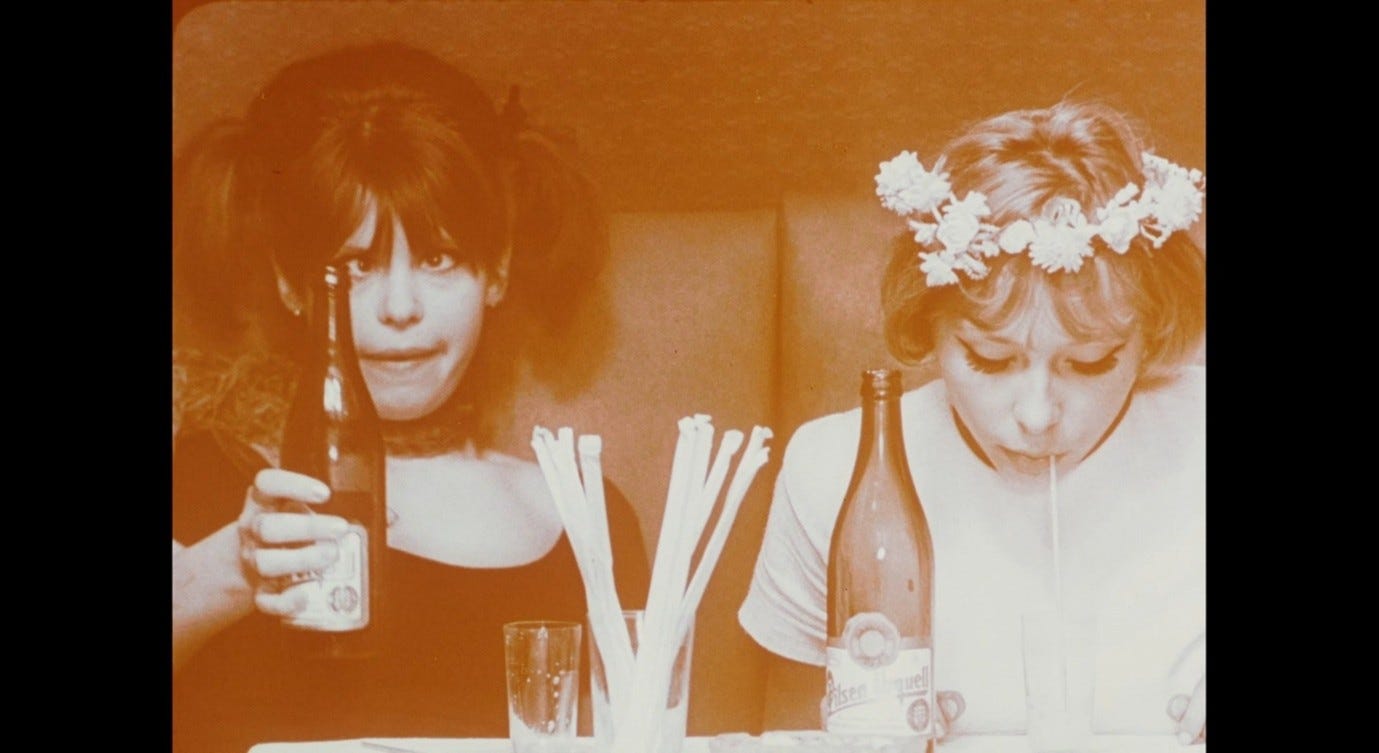

Věra Chytilová’s Daisies offers a similarly playful, but much more disturbing, take on the looking/living dichotomy, and one that is closer to what we find in Red Desert. ‘No one is paying attention to us,’ say the young women around whom the film revolves, as they wander through a grey street much like Red Desert’s Via Alighieri, dressed in blue and green and standing against complementary green and blue doors as they pose for the camera.

‘See how you look?’ says one of the women, opaquely, after letting a veil drift across her face.

The Czech phrase, ty ale vypadáš, literally translates (I think) as ‘but you look,’ the verb vypadat meaning ‘look’ in the sense of seeming or appearing. But there is a play on the act of looking as well, because the other woman, having been asked to contemplate her appearance, does not look into a mirror but into the camera lens, which looks at her. When we first cut to her, she is looking up; she brings her eyes (and then her whole face) down so they are level with the camera lens, and we see how elaborately painted the skin around her eyes is.

If these components of her ‘look’ – the upward gaze, the movement of the eyes to meet the camera, the heavy make-up – seem highly artificial, the artifice is disrupted by a quick movement of her mouth, a kind of ironic smile, which feels more natural and quotidian, like Claudia’s shrugs and silly faces in L’avventura.

Chytilová plays with the dynamic of looking/looked-at in a way that tends towards nihilism: what if you are all made up but no one is looking, or what if you look intensely but find (with a shrug) that there is nothing to look at? There is something comically futile about looking at a person’s ‘look,’ as in Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida when Pandarus runs out of ways to praise Hector and is reduced to saying, ‘Look how he looks.’8 The women in Daisies go to a river to reflect on their identity crisis, standing in a rocking boat with water filling the frame around them:

Know what worried me? That we were invisible! I thought we’d evaporated! Why didn’t they notice us? Why is there water here? Why? Why is there a river here? Why?

As in Red Desert, this fear of turning to liquid and then vapour is triggered by a meeting – or failed meeting – of looks, a sense that we cannot be seen by other people and that they do not appear to us.

Daisies begins with its two protagonists deciding that the world around them has become so irredeemably awful that they have no choice but to sink to its level, and to find worse and worse ways to live. Living badly, for these two women, is intimately tied up with ways of looking. Their disruption of social norms takes a similar form as in the climax of PlayTime, in that they target clubs, restaurants, and dining rooms. But whereas Tati connected the restaurant-within-a-restaurant with his own margin-conscious approach to composition, Chytilová connects the women’s violation of spaces with her own disruption of cinematic conventions, constantly ‘messing up’ the colouring, editing, and sound design so that we struggle to know how to look at (or listen to) the film.

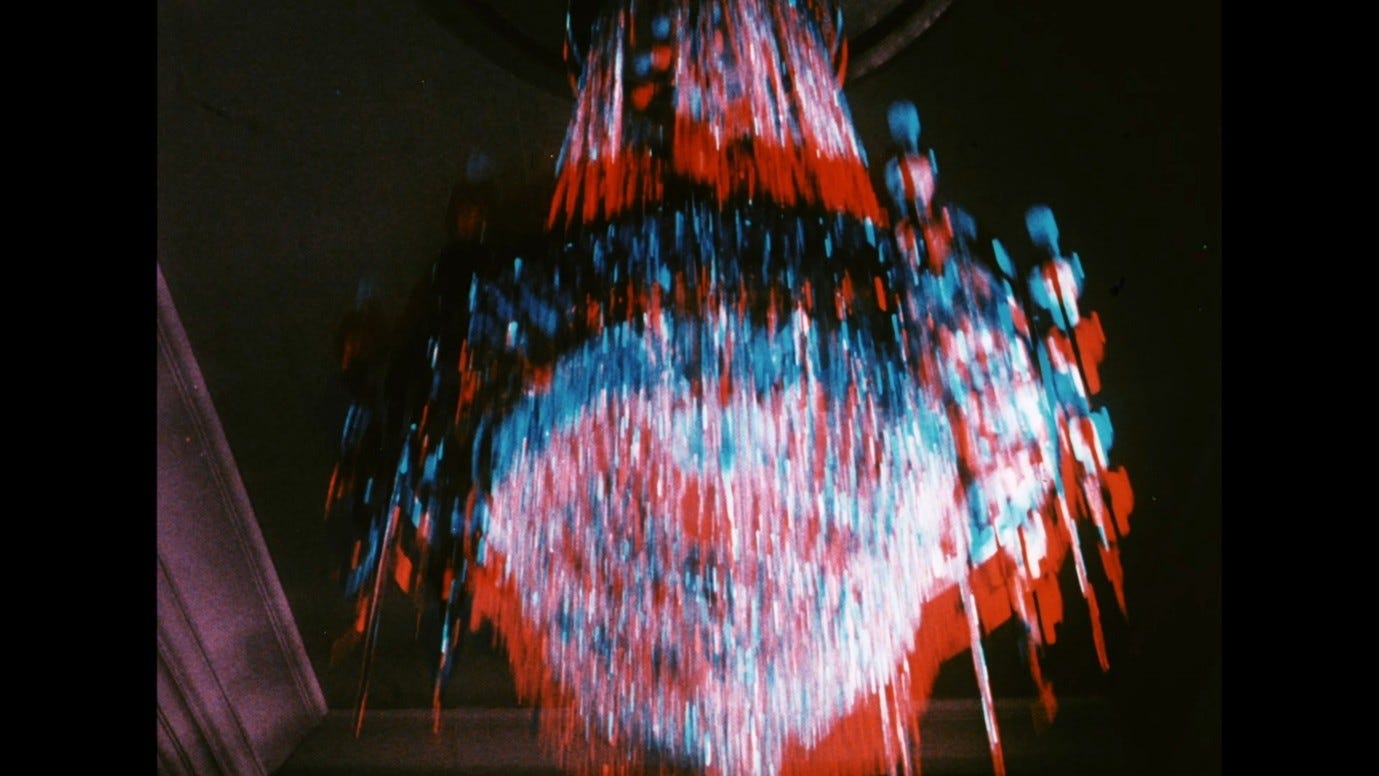

We might remember the red room in Max’s shack when we see the two women sitting in a red booth set within a greenish-beige proscenium at a club.

The red is appropriately confrontational, given that the women are heckling the performers and bothering the nearby customers. Then, suddenly, the whole screen is tinted red, as the women’s anarchic sensibility infects their environment.

When one of them downs a pitcher of beer too quickly, the red tint turns yellow and then green to show how her physical state determines the colour of her surroundings.

As the colours keep changing, we understand that these women are ‘living badly’ in part by refusing to let us look at them in any one stable way.

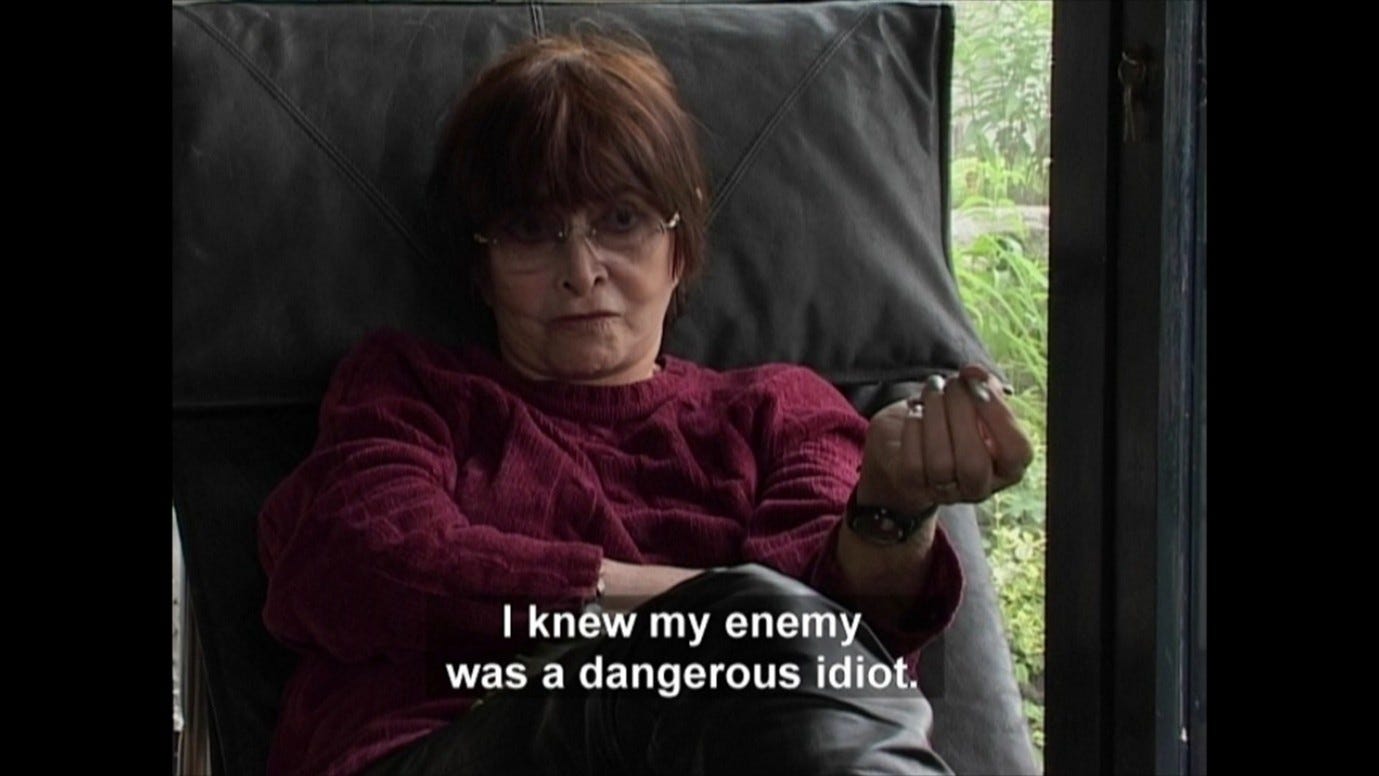

Chytilová spoke of having to ‘make scenes’ to get her way with male film producers, playing on their fear of hysterical women: ‘I knew my enemy was a dangerous idiot,’ she said.9

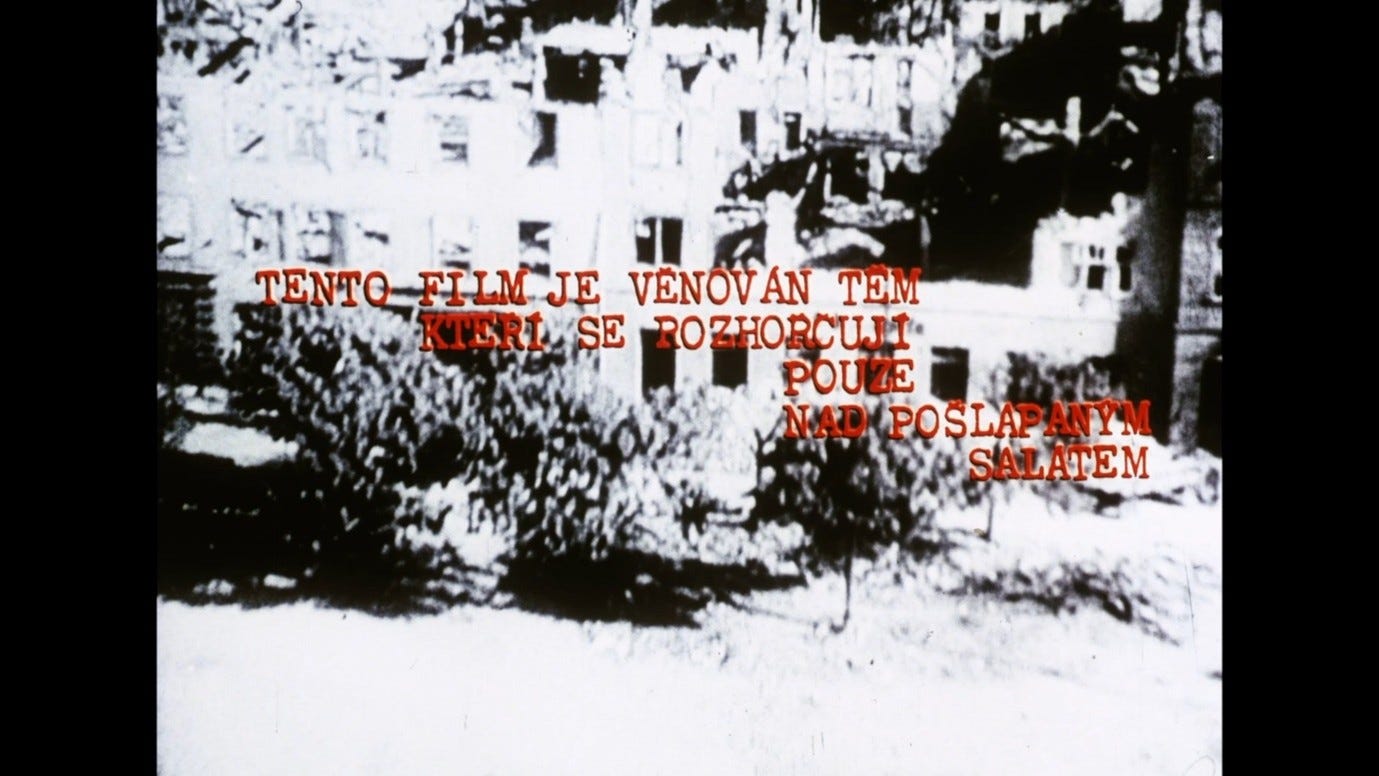

Daisies is intent on driving us out of our minds, if we are the kind of viewers who get upset by stamped-on trifles and improper film grammar. Those elaborate meals, those pretentious establishments, all those ways of doing things – they are the work of dangerous idiots, like the footage of bombing raids that are quoted at the beginning and end of the film.

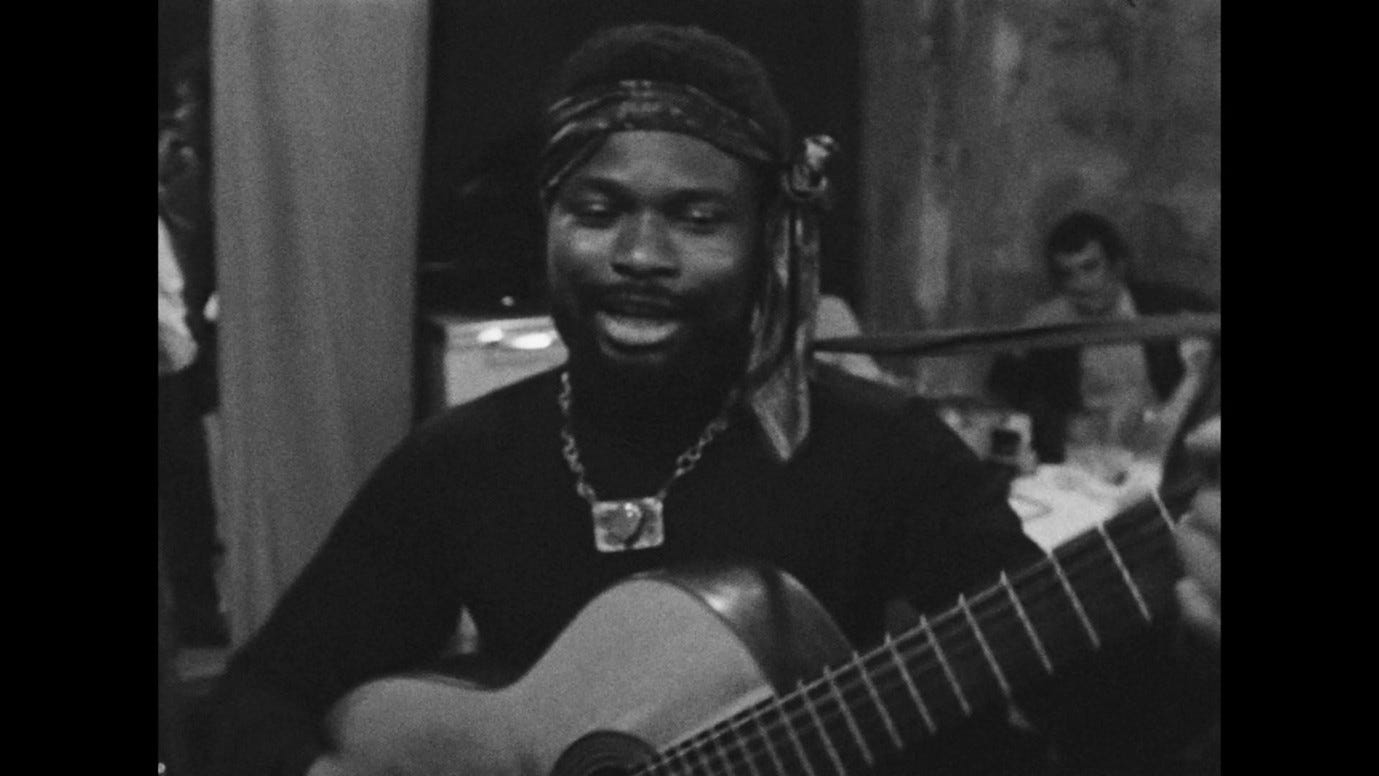

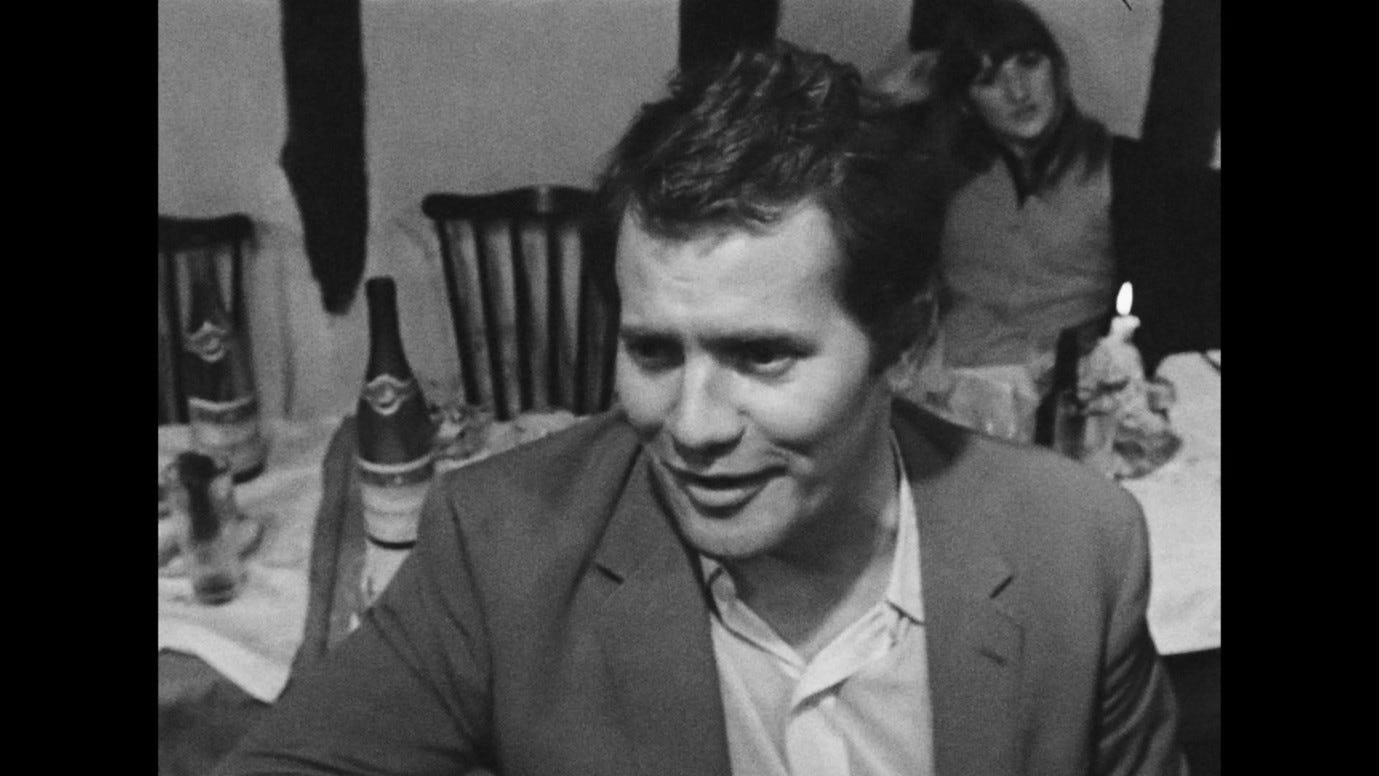

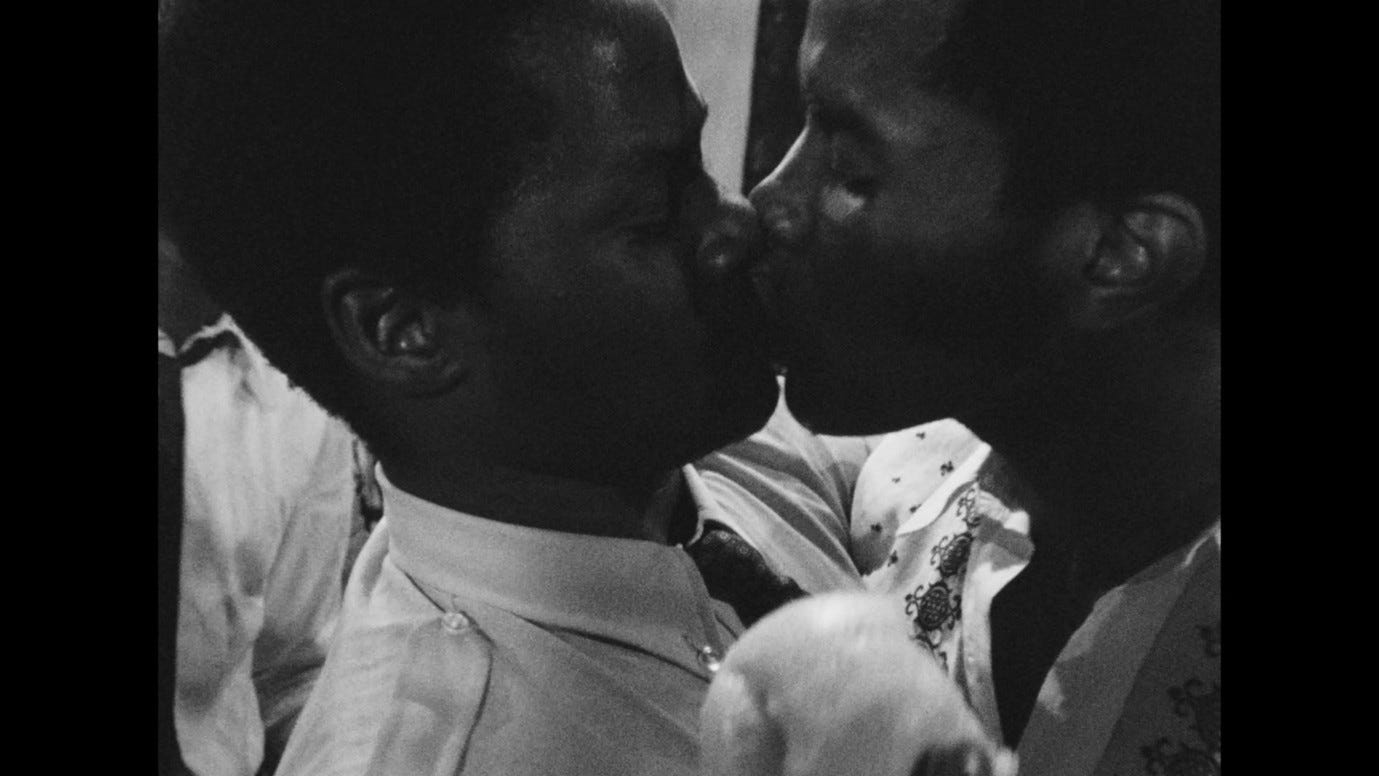

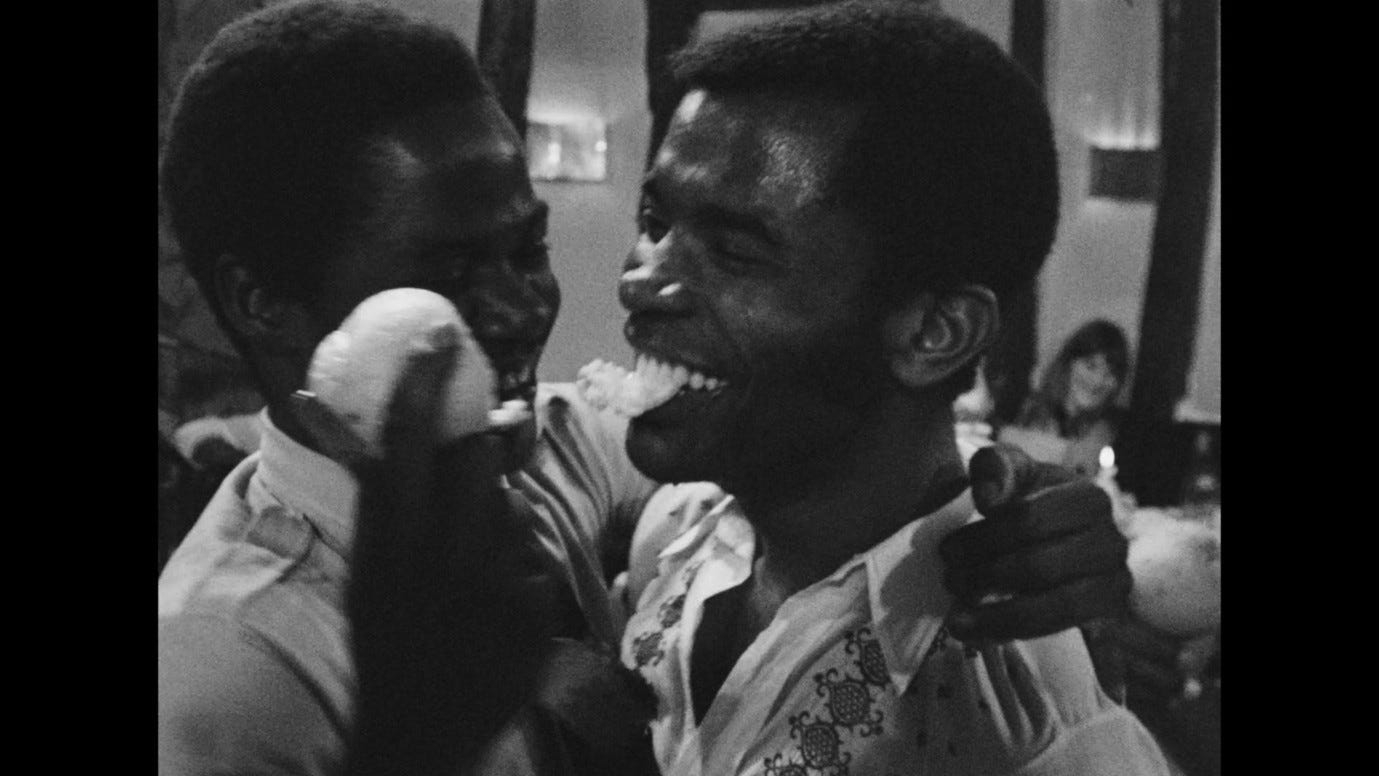

Near the end of Soleil Ô, the film’s protagonist enjoys a rare moment of communal joy, singing and dancing with friends in an atmosphere of liberated play.

But as the Visitor staggers home, depression descends on him again. His inner monologue becomes both more furious and more ironic:

You become good Whites, good Blacks. All of you compassionate. All good Christians. But you know that all contact is out of self-interest. All dialogue is commerce. All aid is investment. All gifts are for future return. All truth can be bought.

He mutters this to himself as he runs from the city to the woods, disgusted by the pretence of ‘goodness,’ the social harmony that papers over the impact of colonialism in this ‘post-colonial’ world. Out in the countryside, he shares a meal with a middle-class family. The children stamp all over the food, to the delighted laughter of the parents.

In this context, anarchic playtime is an object of horror and disgust, an allegory for the complacent, wasteful frivolity of the class that has made the hero’s life intolerable. They smile and laugh and sleep well at night, with a tranquil conscience, all the while nurturing the systemic racism that prevents the Visitor from finding work, a home, or a community.

Daisies has nothing to say about racism, but its climactic feast-and-food-fight has something in common with the one in Hondo’s film. Whereas the children in Soleil Ô were encouraged to waste food by their parents, the women in Daisies have discovered a banquet about to be consumed/wasted by some unspecified dignitaries, who (it is implied) will be outraged by the indignities wrought upon these sophisticated dishes.

The women do not waste the food, they eat it, even after throwing it at each other. Indeed, part of what makes them transgressive is that, throughout the film, they care more about eating than the social infrastructure that is kept in place by fancy meals like this one.

When our heroines, wrapped in newspaper, try to make up for their bad behaviour by putting the broken food back onto the broken plates, this is a parody of the same self-deluding rectitude that Soleil Ô rails at, and a come-down from the liberated play that has dominated the film until now. Again, the keynotes are hypocrisy and futility: for all the women’s efforts to tidy up, the chandelier still falls on them, the bombs still blow everything up. You cannot watch this film properly and you cannot live properly. If you think you can, Daisies tells you, you are not paying attention.

Red Desert has a place amongst these films because it asks the same questions – how to see and how to live – in the context of a similar shift in tone. There is the anarchic, free-spirited explosion of joy, then there is the come-down and the movement into grey depression, into that feeling of being ‘lost’ embodied by the fog in Red Desert, the forest in Soleil Ô, the traffic jam in PlayTime, and the whispering clean-up-and-annihilation at the end of Daisies. The most important thing these films have in common is a spirit of radical questioning. There is no one answer, and perhaps no answer at all, to either of the questions Giuliana and Corrado ask each other. As Giuliana stares into the sea, or into the fog, we feel the intensity of her crisis: her way of looking and her way of living seem fundamentally at odds with what is prescribed by the world around her. As in the other films just mentioned, I think we are also meant to feel that this reflects a problem in that world, in all of us – a problem in how we look (and are looked at) that renders our way of life untenable.

Next: Part 23, Valerio and the chemistry set.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 99

Paulicelli, Eugenia, Italian Style: Fashion and Film from Early Cinema to the Digital Age (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p. 287

Tornabuoni, Lietta, ‘Myself and cinema, myself and women’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 185-192; p. 188

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Preface to six films’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 57-70; p. 62

Tornabuoni, Lietta, ‘Myself and cinema, myself and women’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 185-192; p. 191

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Preface to six films’ (trans. Allison Cooper), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 57-70; p. 59. Italian text from Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), p. xi.

Tassone, Aldo, ‘The history of cinema is made on film’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 193-216; p. 196. Italian text from Ferraro, Pietro, ‘Alain Delon: 10 film e curiosità per ricordare l’attore di “Zorro” e “Rocco e i suoi fratelli” morto a 88 anni’, Cineblog (18 August 2024)

Shakespeare, William, Troilus and Cressida, Act 1, Scene 2, ll. 206-207, The Folger Shakespeare.

Bralic, Jasmina (dir.), Cesta (2004), from Daisies (blu-ray, Second Run 2018)