Everything That Happens in Red Desert (29)

What Corrado sees and feels

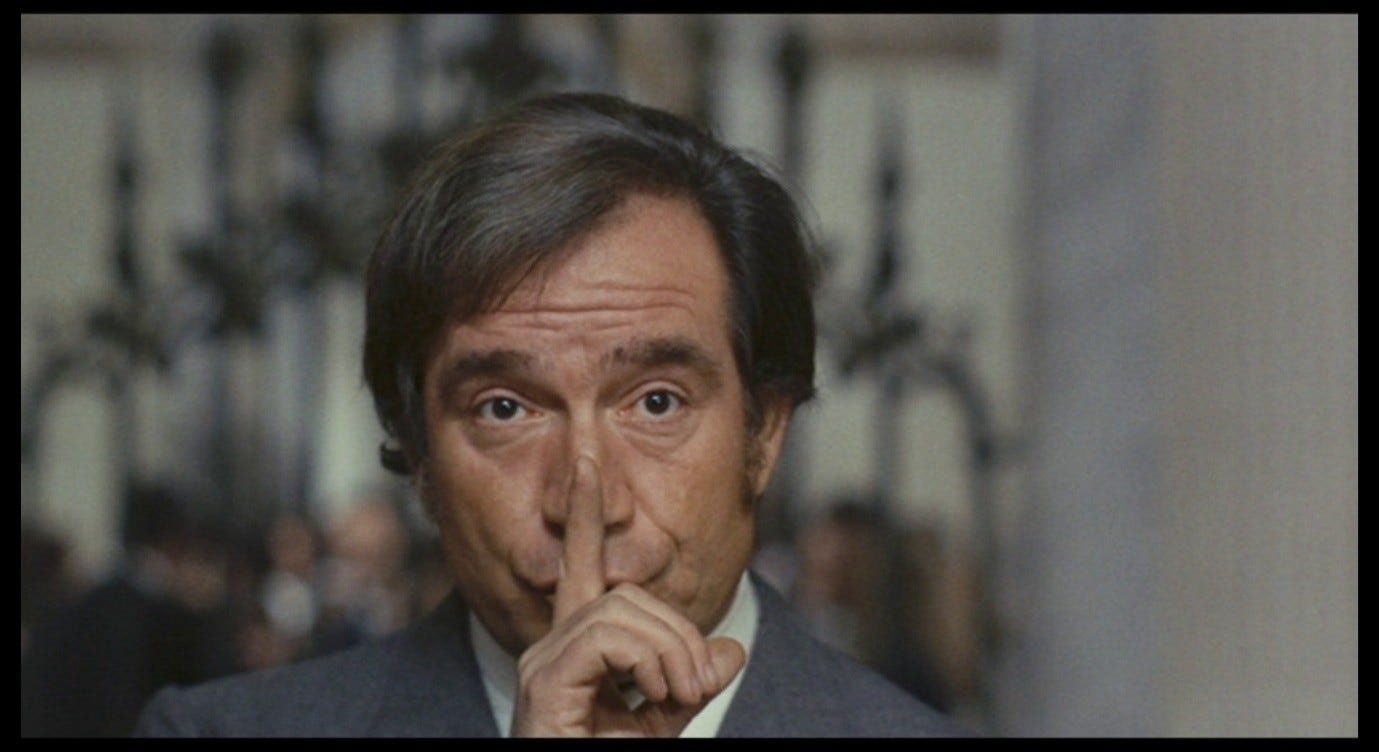

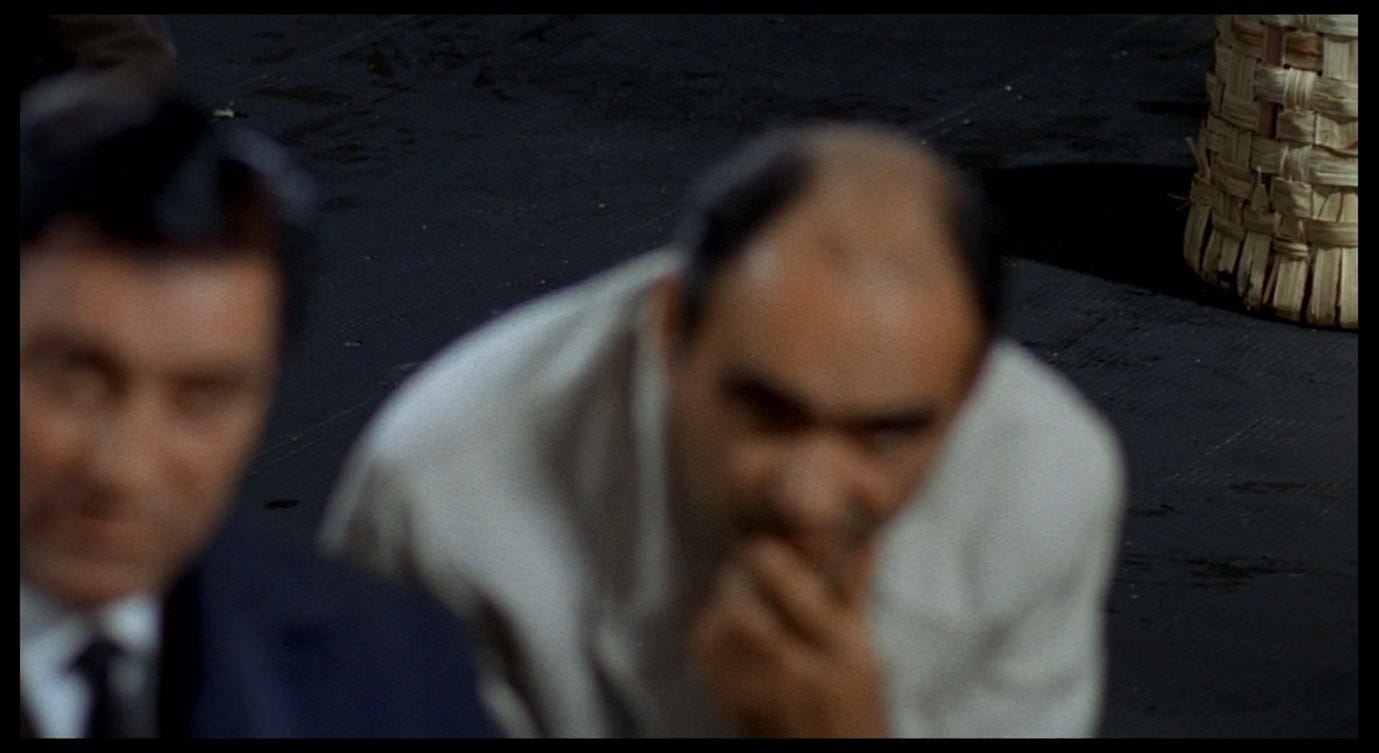

There are two more shots in the interior-set part of the briefing sequence, before Corrado leaves the warehouse. In the first, we see two men out of focus in the foreground, one of them stroking his chin and looking slowly up towards the camera (and presumably towards Corrado), with the grey floor and part of a wicker basket in focus in the background.

The man who looks up at us has one finger placed over his lips; he seems thoughtful, perhaps worried about the Patagonia trip, but his face is too blurred for his emotions to be legible. The man next to him is looking steadily in our direction, his face more thoroughly anonymised by the blurring effect.

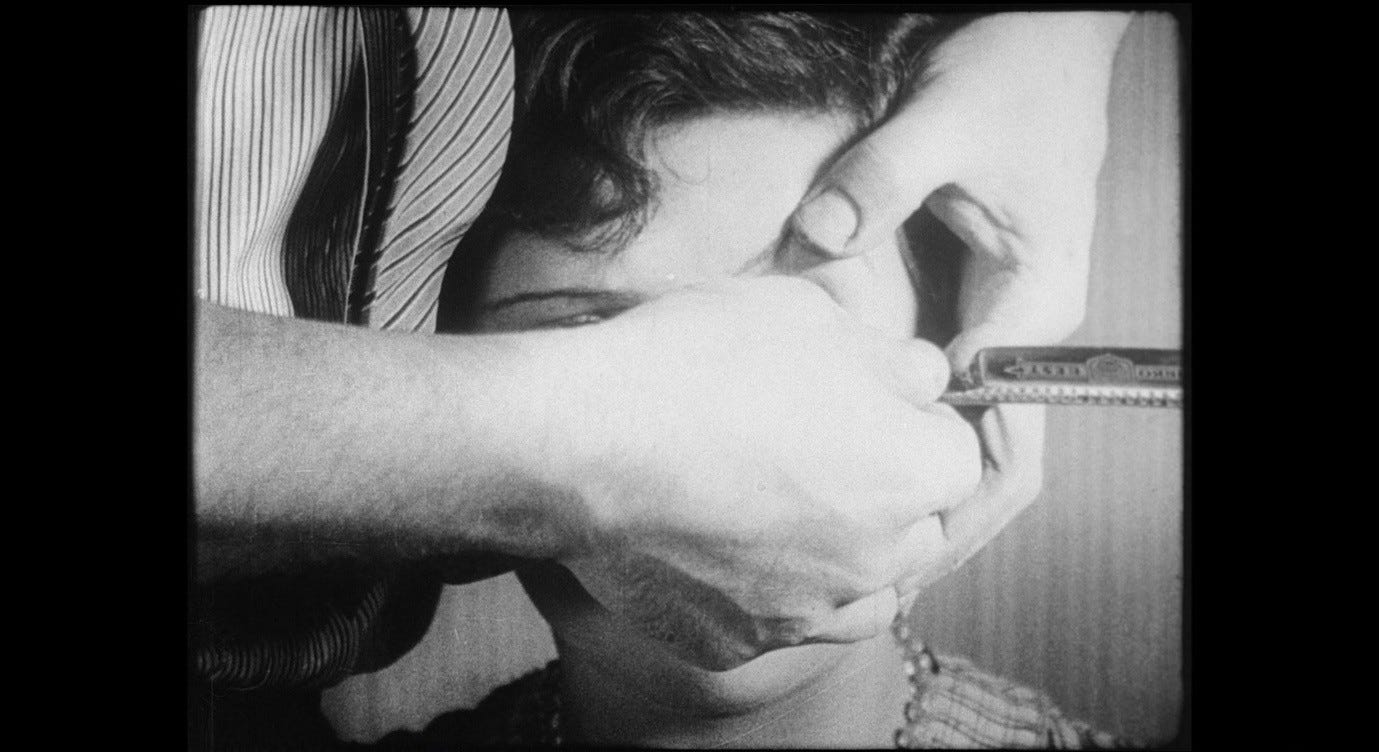

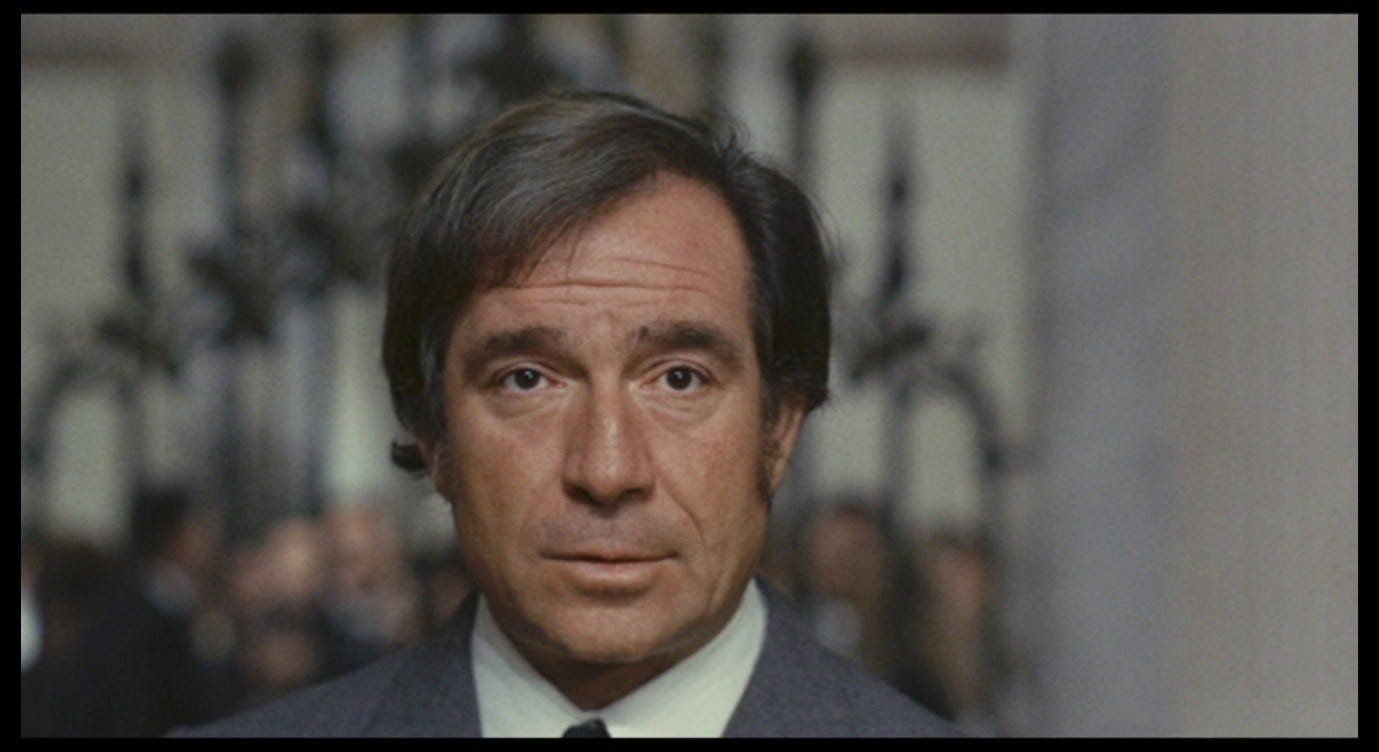

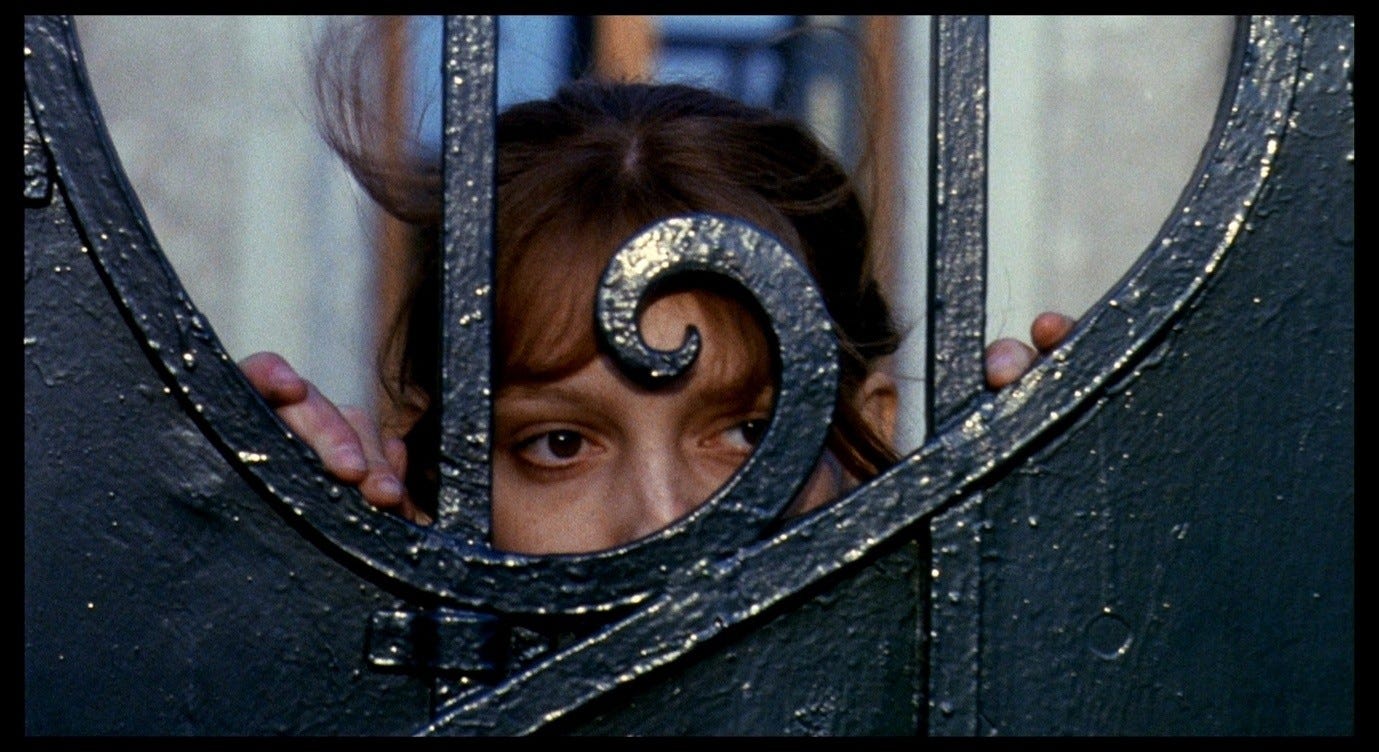

In the second shot, we are confronted with another face that is in focus and more easily legible. This young worker appears hauntingly vulnerable, like a soldier in a World War 1 photograph, and he looks at us (and, again, presumably at Corrado) as though he were pleading not to be sent to his death. One corner of his lip turns up slightly in a kind of wry smile, perhaps mirroring the cynicism we just saw in Corrado’s face. ‘Of course I must exploit this man.’ ‘Of course I must be exploited.’

The camera tilts upwards, away from the young recruit. Another face – much closer but out of focus, barely recognisable as a human face – passes through the far-left portion of the frame.

More than ever, the camera’s gaze fixates on inanimate objects. It follows the stack of wooden barrels, then adjusts focus slightly to follow the stack of wicker baskets piled high against the back wall, eventually leaving these behind to follow the course of a blue line painted on the wall, up to the point where it turns to the left (forming a corner of the blue-outlined rectangle we saw earlier in the sequence).

The questions we will focus on here – what is Corrado seeing, and how is he responding? – are not easily answered, and they are not supposed to be. Like most of Red Desert, this sequence is about a problematic interaction between people, and illegibility is a key part of the problem in this case. The workers and Corrado look at each other. Each side of the interaction finds something missing in the other, or fails to find something in the other. These workers seem to be saying, ‘Who are you?’ and ‘You don’t see us,’ while Corrado seems to be saying, ‘Who are you?’ and ‘You’re not there.’

Either the workers are out of focus or Corrado’s eye drifts away from them, but in any case he is drawn to ‘the surrounding objects [gli oggetti attorno],’ as the screenplay puts it.1 This phrase reminds us of Giuliana’s comments about what she has attorno in the SAROM sequence: her point was that Corrado was one of those oggetti that she would have to take with her if she went away, because the things she has around her are part of her. Earlier in that scene she was more focused on objects (‘even the ashtrays’), but as the conversation became more intimate she shifted her focus to an interpersonal connection. Corrado moves in the opposite direction, ceasing to interact with the people in front of him, failing to answer their questions, blind to the expressions on their faces, contemplating the baskets and the wall markings instead.

The shot that follows the blue line up the wall echoes the one near the start of the SAROM sequence, in which the camera traced the progress of the pipe conveying oil to the nearby ship.

In Part 25, I argued that there was an ambiguous relationship between the camera’s gaze and Giuliana’s: she was exploring the rig and looking at its various mechanisms, but the camera seemed to be doing the same thing independently of her, perhaps with a steadier eye and one more sympathetic to these industrial marvels. There is some of this ambiguity in the briefing sequence, especially in the moment (discussed in Part 28) when the camera glances at a doorway, then shows Corrado looking in the other direction. However, in the subsequent shots of workers staring at the camera, there is a stronger sense that we are inhabiting Corrado’s point of view, that the camera is seeing as he sees.

On the one hand, Corrado’s vision is becoming infected by Giuliana’s, distracting him from his work. On the other hand, his vision remains that of the capitalist robot-eye that prefers objects (especially functional ones) to people. He is troubled by a breakdown in definitions and distinctions but he still sees these workers as things to be exploited. Most importantly, Corrado is losing his sense of why the South American project is important, but that investment in his work is not replaced by an investment in human relationships. This is not the sort of film where Corrado would realise he has been searching for love all along, abandon his work meeting, and run to Giuliana to tell her she has opened his eyes to the true meaning of connectedness.

In his essay, ‘The Cinema of Poetry’, Pier Paolo Pasolini identified Red Desert as marking a significant advance in Antonioni’s use of cinematic ‘free indirect discourse’:

In Red Desert Antonioni no longer superimposes his own formalistic vision of the world on a generally committed content (the problem of neuroses caused by alienation), as he had done in his earlier films in a somewhat clumsy blending. Instead, he looks at the world by immersing himself in his neurotic protagonist, re-animating the facts through her eyes [...] By means of this stylistic device, Antonioni has freed his most deeply felt moment [il proprio momento più reale]: he has finally been able to represent the world seen through his eyes, because he has substituted in toto for the world-view of a neurotic his own delirious [delirante] view of aesthetics, a wholesale substitution which is justified by the possible analogy of the two views.2

For Pasolini, Antonioni’s ‘delirious’ gaze is analogous to that of the ‘neurotic’ Giuliana: by filming the world as he sees it, Antonioni can thereby evoke Giuliana’s state of mind (and vice versa, evoking his own world-view through her). But the distinctions between the protagonist’s and the film-maker’s gaze are also important. In one interview, Antonioni situates the three central characters of Red Desert on a spectrum, with Giuliana and Ugo at opposite ends and Corrado in the middle:

Giuliana cannot adapt to the new ‘way’ of life and she goes through a crisis, while her husband, on the other hand, is content with his lot in life. And then there is Corrado. He has almost got to the point of neurosis and thinks he can cure himself by going to Patagonia.3

In the Godard interview, Antonioni ruefully describes his encounters with cutting-edge researchers, and with young people who are at ease with the latest advances:

I look at all this with great envy. I really wish I were already part of that new world. Unfortunately, we are not there yet, and for older generations, such as mine, yours, or that of people born just after the war, this is a real tragedy.4

Following up on the passage just quoted, Godard comments, ‘And yet the male heroes of your films are part of this mentality. They are engineers; they are part of this new world.’ If Antonioni feels shut out from the new world, how can he write these ultra-modern male protagonists? ‘No, absolutely not,’ replies Antonioni, and proceeds to explain why Corrado is an ‘almost romantic figure’ who ‘hasn’t the least idea of what he should be doing.’ (This was the passage, quoted in Part 28, that prompted Richard Letteri to challenge the notion of Corrado’s ‘romanticism’.)

If Ugo is a robot and Giuliana is a human, Corrado is a kind of hybrid entity, embodying the tension between these two states. Antonioni’s conflicted comments about the ‘new world’ – he is fascinated by it and eager to belong to it, but also feels alienated and excluded from it – represent one manifestation of this tension, and Corrado represents another. In Part 21, I noted the overlaps between Corrado’s and Antonioni’s comments about having a ‘peaceful conscience.’ In Part 26, I noted the similarity between Corrado’s questioning of Giuliana and the behaviour of the interviewer in ‘Attempted Suicide’ (who seemed to be an ambiguous stand-in for the director). Now, in the briefing sequence, we see an alignment between the camera’s curious, distracted gaze and that of Corrado. It would be reductive to call him a stand-in for the director, but he does seem to share many of Antonioni’s conflicted feelings about the world he lives in.

As Antonioni also said to Godard, in response to a question about whether Red Desert helped him solve any personal issues:

Filmmaking means living, and so it also means solving personal issues [...] The new themes that we can deal with today are the ones I have already mentioned. I don’t yet know how to deal with them, how they should be presented. In Red Desert, I think I have at least touched upon one of them, even if I haven’t treated it fully.5

This hesitancy, this sense of not having dealt with these themes fully, may have something to do with the inscrutability of Corrado as a character, and the sense that he is not fully or coherently developed (which may in turn explain Richard Harris’s frustration with the role). At one end of the spectrum, Ugo is stable to the point of dullness, a one-dimensional character who is exactly what he seems; at the other, Giuliana is correspondingly complex, a subtle filter of reality and an endlessly fascinating subject for analysis. The one is a chilling utopian ideal, fully at ease with the new world; the other is nightmarishly victimised, and all but destroyed, by that same world. Corrado is on the verge of becoming both of these figures: he is about to fulfil his project in Patagonia and he is about to undergo his own ‘neurotic’ breakdown.

With this in mind, let’s return to the ‘blue line’ shot. This is one of several poetic moments Pasolini singles out as testifying ‘to a deep, mysterious, and – at times – great intensity in the formal idea that excites the fantasy of Antonioni.’ He describes the shot as a

close-up of a distressingly ‘real’ [struggentemente ‘vero’] Emilian worker, followed by an insane pan [folle panoramica] from the bottom up along an electric blue stripe on the whitewashed wall of the warehouse.6

As with the other examples he cites, Pasolini frames this one in terms of dramatic contrasts. The worker is authentic, specifically ‘Emilian’ (i.e. he looks like he really comes from the Emilia-Romagna region in which Ravenna is located), to the point that the effect is distressing: his unhappy, exploited look appears un-simulated. By contrast, the camera movement that takes us away from him is ‘insane,’ and is therefore close to being one of those rare cases Pasolini celebrates ‘in which the poetic quality of the language is foregrounded beyond all reason’ (here he is referring to Un chien Andalou).7

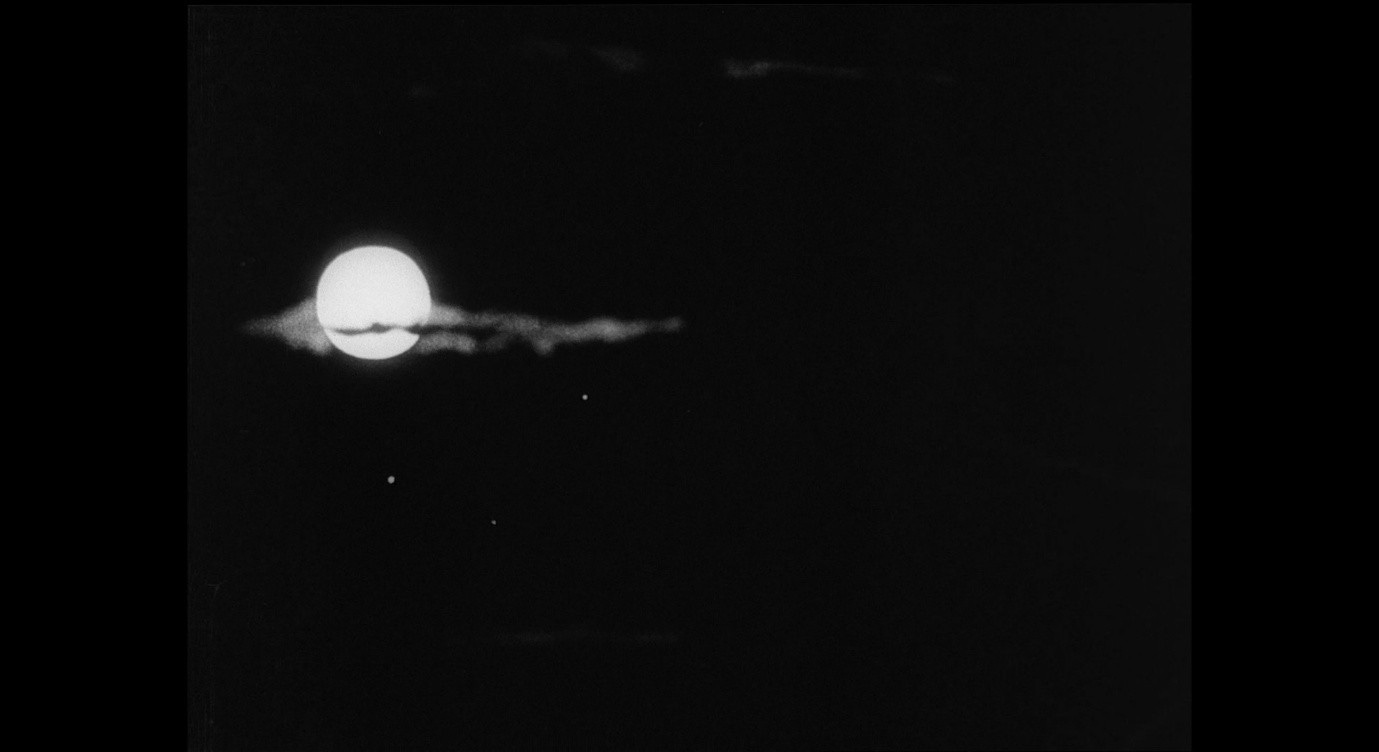

The non-insane version of the blue-line shot in Red Desert would linger on the realness and authenticity of the Emilian worker, building our understanding of him and his colleagues, but here the camera defies reason. The documentary-like image of a non-professional actor is merely the starting-point for a journey into complete abstraction. As in Un chien Andalou, when the razor-across-the-eye is intercut with a thin, dark cloud crossing the moon, there is a sort of ‘cause and effect’ operating in this shot, but it is dream-cause-and-effect, without any clear sense of reason or logic. Hence its ‘deep and mysterious intensity.’

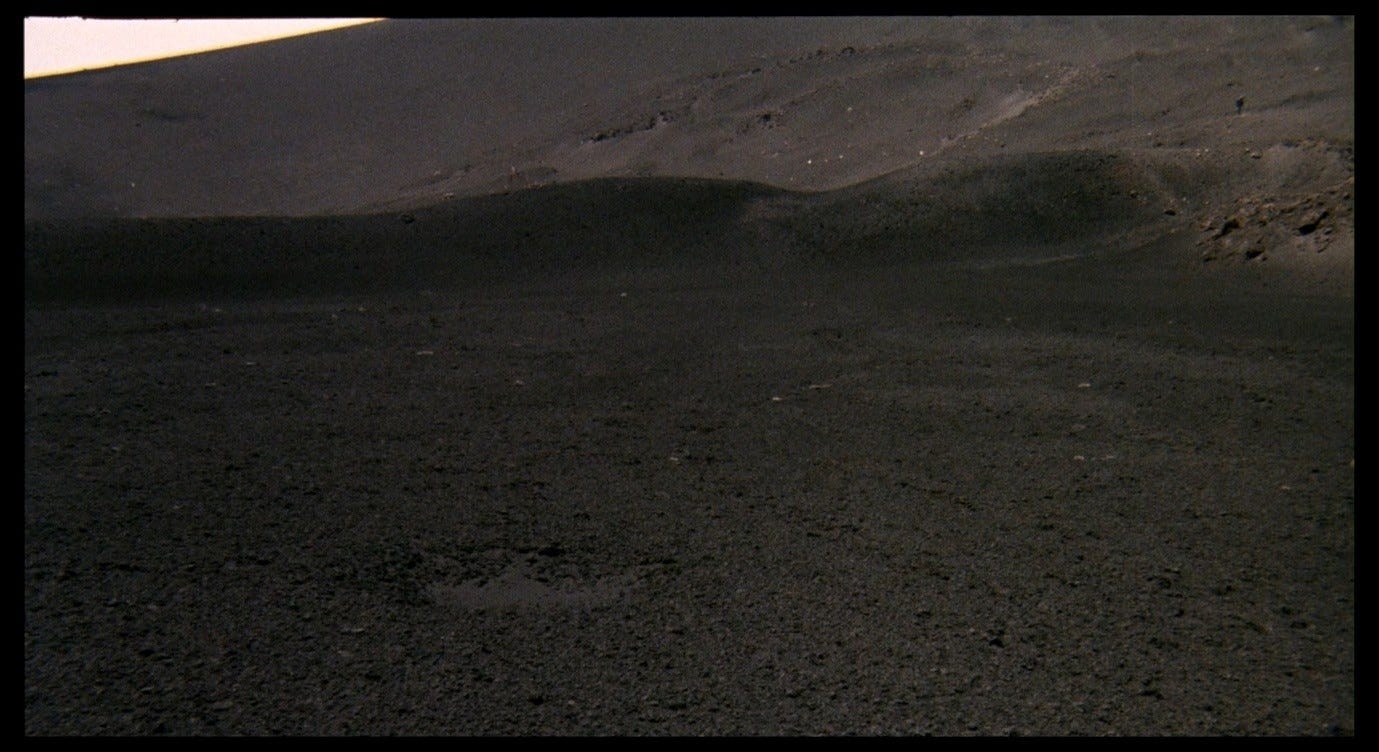

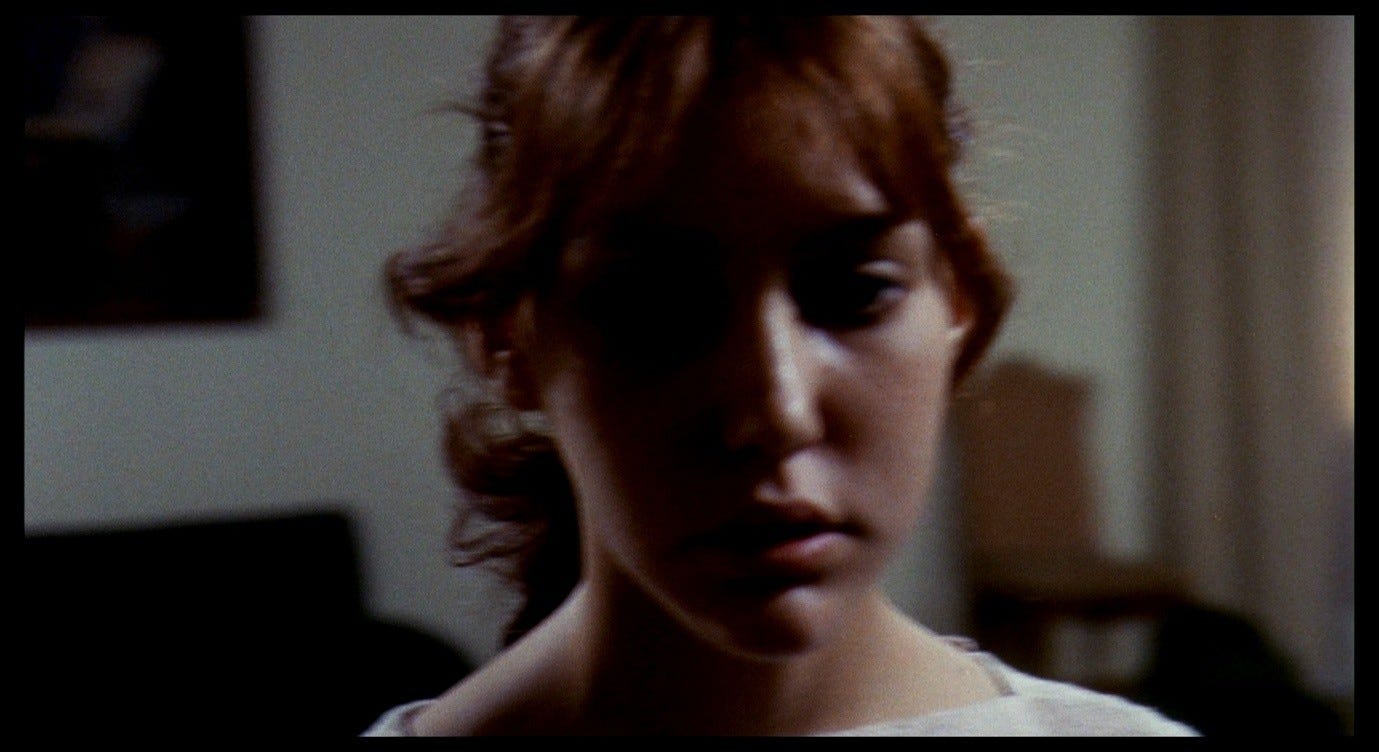

Pasolini himself uses similar effects in Theorem, inserting images of a volcanic desert throughout the film to suggest something about the characters’ experience. Paolo, played by Massimo Girotti, is undergoing a crisis like Corrado’s, his sense of professional identity (as an industrialist) shaken to its core. The camera adopts his point of view as he staggers through his bedroom, holding up a hand against the sunlight pouring through the out-of-focus window.

We cut to an image of the desert plain, over which clouds cast moving shadows, blocking out the sun as Paolo blocks it from his eyes; perhaps Pasolini was thinking of the moon, cloud, and eyeball in Buñuel and Dalí’s film.

Then we are back at the window with Paolo, looking out at the lawn, on which the trees cast spindly shadows.

In case we feel too secure in reading the inserted shot of the desert as portraying an internal state – a legible symbol for Paolo’s mental condition – the film’s final sequence ‘blurs the distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic, [and] challenges even our symbolic interpretation,’ as Simona Bondavalli puts it.8 We see Paolo literally walking naked into the desert, spreading his arms and letting out a primal scream. Paolo carries out this action, Pasolini says in the novel of Theorem (written at the same time as the film was being made),

as if he could not distinguish reality from its symbols; or else, perhaps, as if he had decided to cross, once and for all, the vain and illusory boundaries which divide reality from its representation.9

In Pasolini’s next film, Pigsty, those vain and illusory boundaries have dissolved even further: the modern narrative about the industrialist and his son is intercut with a story of medieval cannibals in a volcanic desert. Ninetto Davoli appears in both story threads, like a time-travelling witness to the ambiguous poetic connections Pasolini is making.

Both films are using these juxtapositions to draw associations between certain feelings and ideas. Paolo blinded by the sun is like Paul on the road to Damascus or other biblical figures made to wander in deserts, but his revelation cannot be encapsulated neatly in words: it issues in a scream that transcends reason. As Paolo says in the poem that concludes the novel:

the symbol of reality

has something reality does not have:

it does not represent any meaning

and yet it adds to it – by its very

representative nature – a new meaning.

But – certainly not as for the people of Israel or the apostle Paul –

this new meaning remains indecipherable to me. […]

It is impossible to say what my scream

is like; […]

In any case this is certain: that whatever

this scream of mine tries to say [voglia significare]

it is fated to last beyond any possible end [fine].10

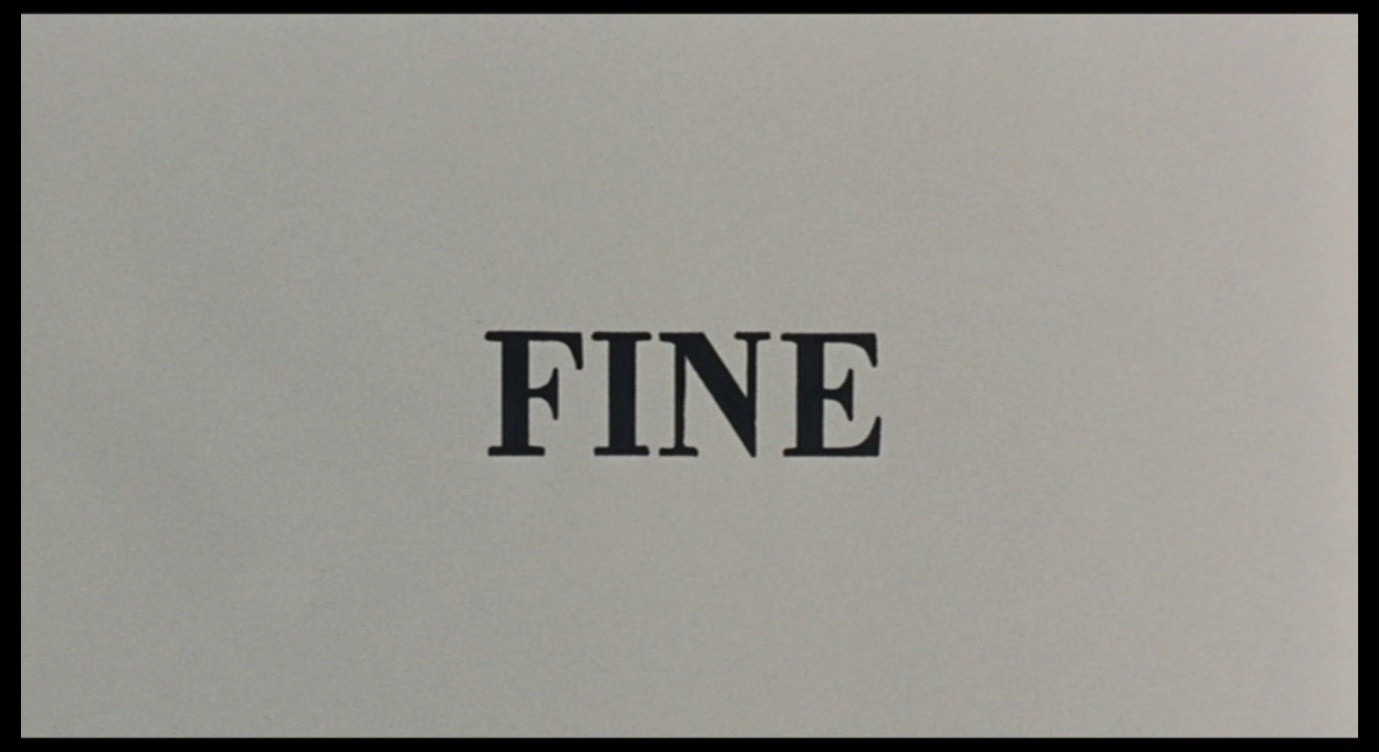

The symbol’s meaning is indecipherable, so what it signifies – or its will to signify something – therefore extends beyond the ‘FINE’ that marks the end-point of the work of art. In the film, Paolo has turned away from the camera and is still screaming when we cut to the ending title-card. His gesture travels away from us, into the smoke rising from Etna.

Pigsty draws associations between modern industry, the Holocaust, medieval soldiers scavenging for food, and a young man having sex with pigs (who ultimately devour him), and it ends not with a scream but with an injunction to be silent. What happened in the pigsty will stay in the pigsty: rather than lasting beyond the end of the film, the meaning in this case is inexpressible because it has been consumed and disposed of, again through the language of cinematic poetry.

More than Antonioni, Pasolini is advancing arguments and ideas – as the title of Theorem suggests, his way of seeing the world is more that of an intellectual poet than of a delirious neurotic – but there are times when he leans into the more emotive Red Desert mode of seeing. ‘They don’t offer results or solutions,’ he said of Theorem and Pigsty. ‘[T]hey are “poems in the form of a howl of despair.”’11 In Theorem, when Odetta goes mad (if that is the right word), the camera circles her and she twirls with it, gradually raising her eyes until they lock with the gaze of the camera-lens.

This folle panoramica is like the circling shot of Giuliana in the red room, but it also partakes of the ‘insane’ quality Pasolini found in the blue-line shot. Theorem is about ‘the irruption of a poetic look into a bourgeois lifestyle,’ says Bondavalli, and the ‘poetic lens offered by the mysterious Guest to his hosts is placed on the camera as well.’12 Odetta goes outside and looks over the driveway gate, in which a metal ornament (framed in front of her head) contorts in on itself; her hair flies up in similar patterns.

Then she runs along the dark twirling lines in the driveway cobbles, the camera breathlessly following her rapid movements.

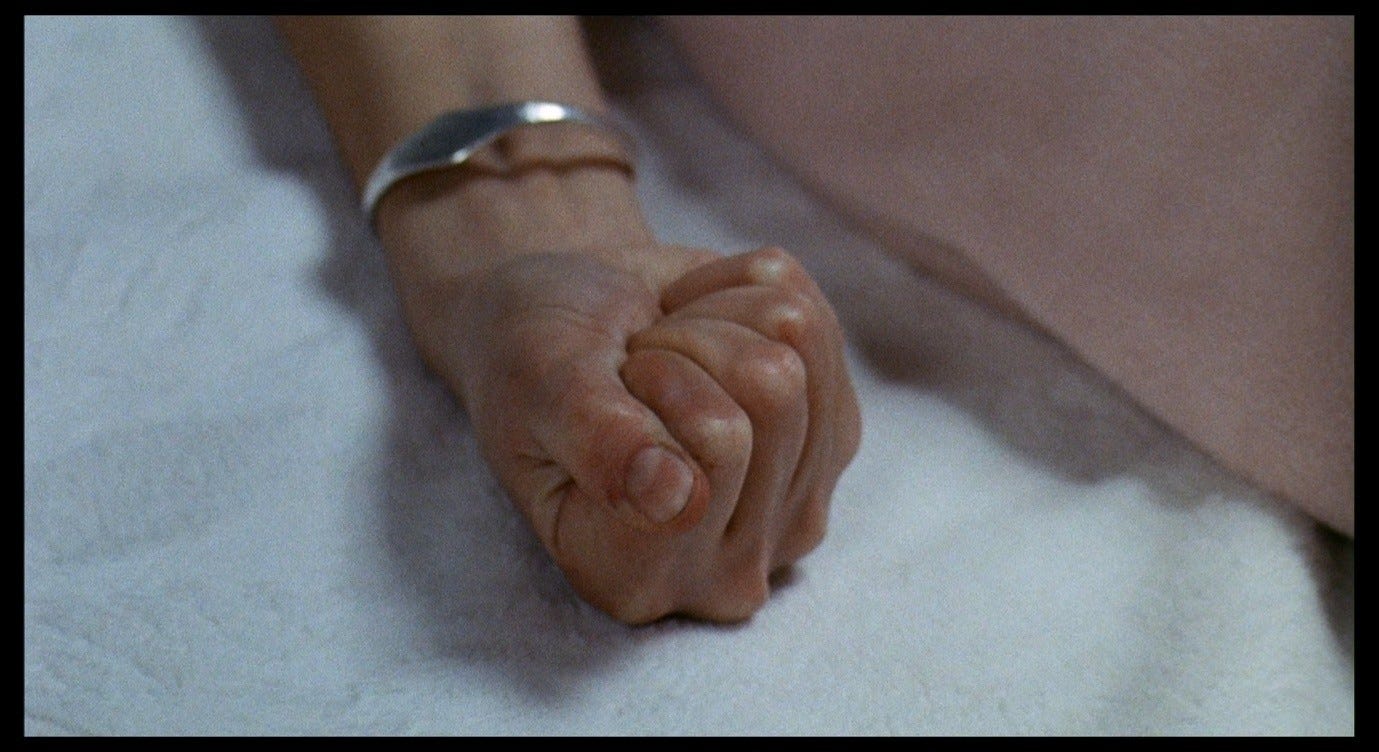

Soon after this, she retreats into the catatonic state she remains in for the rest of the film. Her terminally clenched fist is intercut with an image of the desert: like her father, she is more there than she is here. A volcanic red pervades her bedroom.

The gaze, and the movement of the body, are still connected to the shapes and lines of ‘reality’, but in a way that sends the gaze and the body along arbitrary, irrational paths. Those structures through which the world made sense now expose that same world as nonsense, reduce it in fact to a smoking wasteland. The mobile camera, the effects of editing, and especially the grammar that governs the connections between our eyes, the camera’s eye, and the characters’ eyes – all these tools give cinema its unique capacity for deeply, mysteriously intense poetic effects.

Here are some specific examples of how the dream-cause-and-effect operates in the blue-line shot in Red Desert. The slight upward curl of one corner of the worker’s mouth, coupled with the poignant eye-contact he makes with us (and with Corrado?), triggers our upward journey. Perhaps we infer something critical from this facial gesture and are looking away from it in distress or fear, or perhaps the worker is directing our gaze; perhaps his look and his smile tell us that he wants us to look at the products of his work.

The wooden baskets behind him rise upwards, so we (i.e. the camera) have to raise our eyes to follow them, marvelling at their quantity. What are they for and why are there so many of them? Behind them, a stack of wicker baskets seems excessively copious, to the point that the stack is leaning to the left, threatening to take us off course if our eyes follow, like Odetta losing her way amongst the twirling lines on the driveway. There are too many baskets, perhaps too many to look at – and yet there always seem to be more.

But another stack of baskets behind them is more upright, so we follow that stack’s trajectory instead. How can there still be more of these things? How can these people have made so many baskets? And why are we looking at them – or rather, are we really looking at them? Unlike in the Pasolini films, we do not actually cut to a desert, but are we in some sense looking at the red desert here? The trajectory of this stack takes us into the even straighter vertical line of blue paint, and what can we do but follow this as well, like Paolo walking helplessly into the wilderness? The blue line on the white wall is all we see for a few seconds.

A moment ago, we were looking at the baskets, and before that we were looking at the people, but now we have left both of those things behind. Then this straight line also takes a left turn.

Rather than follow it we simply stop; it made sense to follow it upwards, but not sideways; indeed, this is our cue to abandon the warehouse interior altogether. Odetta’s decision to stop dancing around the driveway, to stop doing anything at all and become an inanimate object, seemed similarly arbitrary, yet also poetically apt, struggentemente vero.

Perhaps, in the warehouse with Corrado, we were never looking at people or baskets at all, but only following lines and shapes with our eyes, directing our gaze according to unconscious, irrational principles. Why did we follow the black tubing on the SAROM island until we found Corrado on the chair-lift? Why do we pan sideways across the workers and demijohns in the factory, and then tilt upwards until the vertical line takes a horizontal turn? When Godard asked Antonioni about his habit of starting or ending shots on abstract shapes, Antonioni explained:

I feel the need to express reality in terms that are not completely realistic. The white abstract line that breaks into the shot of the little grey road interests me much more than the car which is coming toward us. It’s a way of getting close to the character by starting from things instead of from her life – which, after all, is of only relative importance to me.13

In his un-filmed screenplay, The Color of Jealousy, Antonioni describes the effects by which he intends to evoke the main character’s state of mind:

Matteo is driving, holding the wheel with two fingers. The white line down the center of the road seems to run along with a life of its own, curving and twisting through the turns in the road. Matteo stares at the line which gradually gets wider and wider until it becomes the whole glistening white road. […] The headlights of other cars catching up to him are like yellow dots in the rearview mirror which get larger and larger until they fill it completely and cast a yellow glow inside the car. The headlights of oncoming cars are two blinding white spots shooting their beams into his windshield like bullets. The brake lights of cars that Matteo manages to overtake are like two red dots that light up for a moment as he passes them and then go out. Matteo is a bit dazed by it all. […] Matteo’s face seems to focus on a single thought.

MATTEO (voice-over): I wonder what Yvonne is doing right now?14

From the character’s point of view, the movement of the car he is driving has the same effect as a camera movement, causing the static white line on the road to take on a life of its own, then to take over his vision entirely. This happens again when the yellow dots fill the rearview mirror and their colour pervades the interior of the car. This is the poetic language of cinema foregrounded beyond reason, consuming the image, drawing the gaze of the character, the camera, and the audience down a path of ‘neurosis’ and ‘insanity’, in this case specifically related to jealousy. Like Corrado in the briefing sequence, Matteo is thinking about a woman; Corrado may also be wondering, ‘What is Giuliana doing right now?’ But whereas Matteo, in his jealousy, seems beset by threatening forces, Corrado finds himself positioned as the threatening force, eliciting anxious, defensive glances from the men he is exploiting. Within the larger context of the film, we will find that his anxiety is not about being betrayed by a woman, but about betraying her. Something about the juxtaposition of these workers and his thoughts of Giuliana prompts him to find in his surroundings a manifestation of that anxiety.

The upward movement of the blue-line shot evokes the Corrado who, early in Red Desert, ruefully noted that his ambition to work ‘downwards’ (as a mining engineer) has, after his father’s death, been replaced by a duty to build ‘upwards’ in the petrochemical industry. The trajectory of the shot and the copiousness of the products in the warehouse (outnumbering and crowding out the human workers) could also evoke the capitalist mindset, always producing, accumulating, creating a perpetual surplus to keep the profit line ascending towards infinity. Corrado may be confronting his own internalisation of this mindset, or his mindless pursuit of its dictates, and wondering how his crisis might relate to Giuliana’s, or to his developing relationship with Giuliana. And yet even this seems too neat a summary of what Corrado sees and feels. The whole sequence, with its foregrounding of exploitative worker-manager relations, seems designed to hint at these meanings, but also to defy them with the ‘insanity’ that Pasolini celebrates. This is not Ingrid Bergman confronting the dehumanising labour of the factory workers in Europa ’51, nor Gian Maria Volonté exposing (by example) the consequences of treating people as machines in The Working Class Goes to Heaven. As Antonioni says, the drift into abstraction is ‘a way of getting close to the character,’ in part by getting away from the ‘distressingly real’ (to use Pasolini’s phrase) aspects of their actual life.

We are finding our way back to Giuliana here. She was concerned for the fate of Mario, the worker Corrado wanted to exploit, but her concern was more rooted in her own sense of dislocation from reality (and her projection of this crisis onto others) than in socialist or anti-capitalist ideals. At the start of the film she tried to connect with the striking workers, but not by joining their protest or aligning with them politically. Because she confronts and challenges aspects of the industrial environment, her ‘protest’ against these things cannot help but seem political at times. But it is not primarily political, and not primarily a protest. It is, rather, a revelation: she clashes with the world because she sees something terrible in it.

In a similar way, what Corrado sees in the warehouse and the way in which he sees it cannot help but have a politicised edge, but his revelation is more disturbing than a moral crisis about the nature of his work. The effect of the blue-line shot goes beyond ‘What am I doing to my employees?’, into the realm of ‘What am I looking at?’, ‘What should I look at?’, and ‘What am I supposed to do with my eyes?’ It makes sense that part of the horror in this revelation consists in the blending of perspectives: this is Corrado’s gaze, and Giuliana’s, and Antonioni’s, and the camera’s, and the robot’s, and capitalism’s. The film even makes us unsure of whose eyes we are looking through, let alone what they are seeing or why they are looking at things in this way. This blending of perspectives is all the more unsettling because what we see – ‘reality’ – appears to have been affected by the gaze, or the mindset, of the entity (or entities) looking at it. As well as being distressingly real, the workers are also posed and artificial, as if they really have become like the inanimate objects with which they are visually equated; as if a film could render them inanimate by suggesting this equation. This is their existential crisis too, and we see them as they see (or sense) themselves, lost amongst the empty vessels, unable to retain the focused attention of anyone who might determine their fate.

If all this seems dizzyingly complex, I think its ultimate effect is quite simple. In this moment, we are Corrado, preoccupied with thoughts of Giuliana and haunted by her way of seeing the world, which is in turn haunted by an awareness of other gazes (some of them exploited, exploitative, mechanical, robotic). We feel a certain terror when faced with these revelations, but we cannot fully confront or process that terror, so we repress it. This repressive tendency is a notable aspect of Antonioni’s reflections in interviews – that fascination with Giuliana from which he retreats into an identification with Corrado – and the sequence makes us feel some of that placid alienation, that out-of-place-ness in the ‘new world,’ that he expressed. We are on the verge of a revelation but cannot cross that verge, and this is just as well because the revelation might destroy us, as it all but destroys Giuliana. Part of the placidity in this response rests on a complacent acceptance of, and even appreciation for, the new world. Progress, industry, innovation – these things that are destructive and dehumanising from one point of view are beautiful from another. The film gazes at this beauty with a kind of uncomprehending delight that mingles with and anaesthetises the sensation of terror.

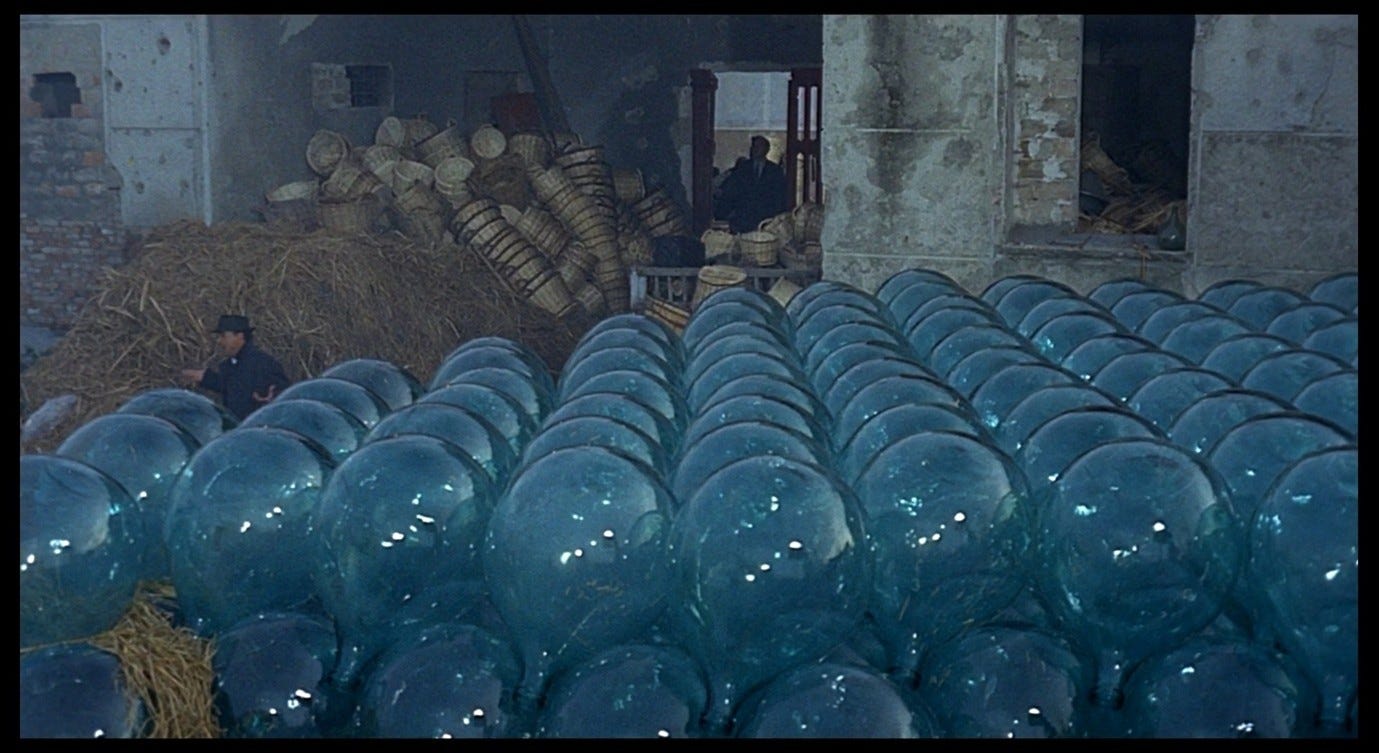

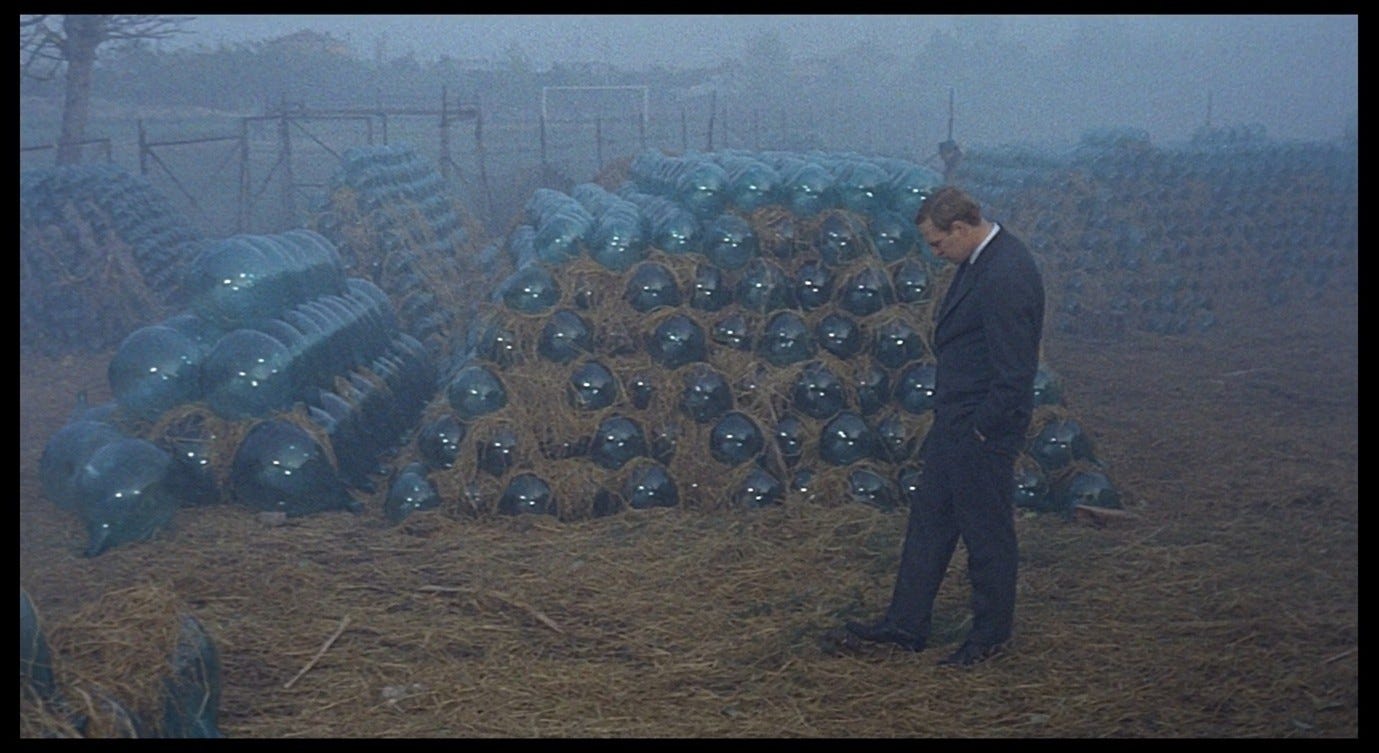

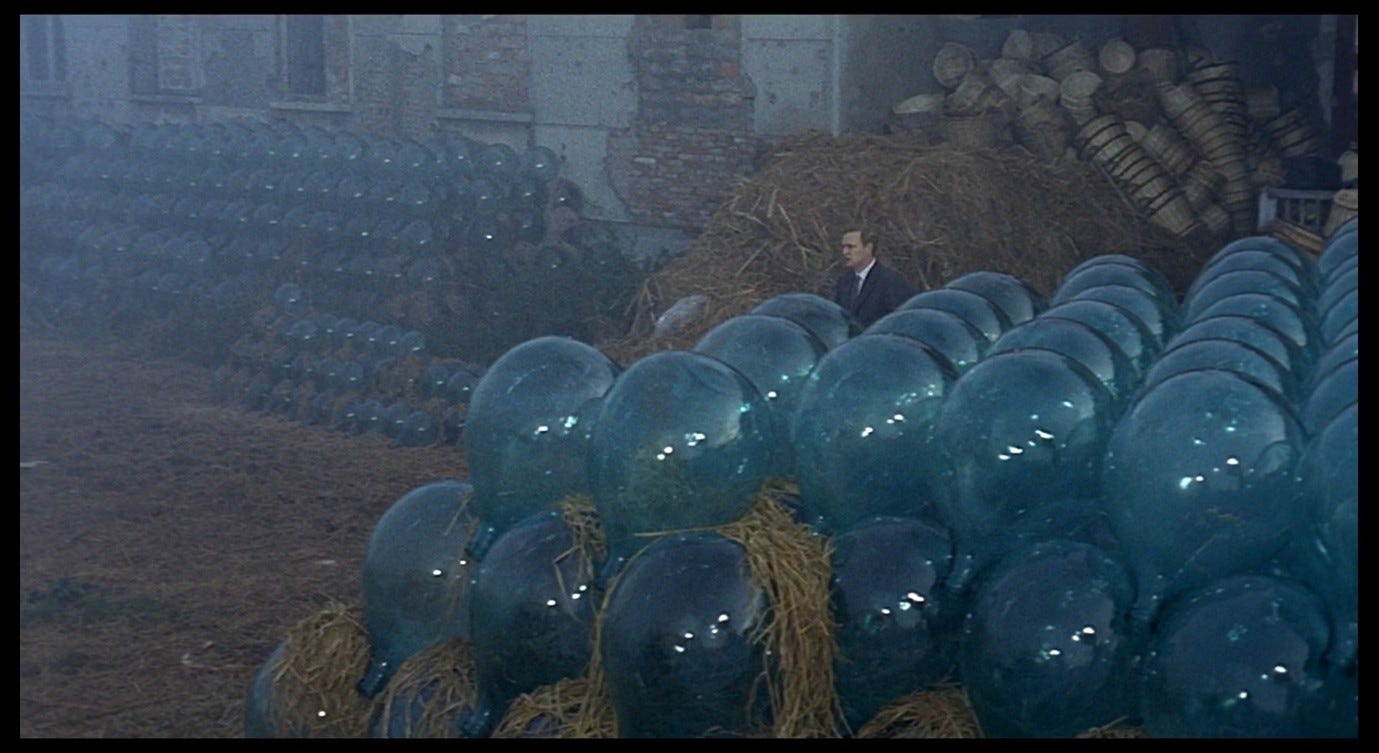

We now venture outside the warehouse. For me, this is the moment when the sheer aesthetic beauty of Red Desert reaches its apex. Corrado strolls into a courtyard filled with vast stacks of luminous blue demijohns.

Angela Dalle Vacche provides some useful historical context for this scene:

[T]he camera surveys a large quantity of blue glass globes and yellow straw containers – an innumerable series of mute demijohns whose proliferation diminishes the size of Corrado’s figure timidly crossing the storehouse. […] While the oversized containers seem to take over the space surrounding Corrado as if they were threatening, artificial creatures at the beginning of a new age, these demijohns are also relics from the past. In fact, the huge shed where Corrado speaks is a glass-blowing factory that has stopped producing demijohns – an important means of transporting and storing wine in Italy for centuries – because everybody now buys or sells wine in expensive liter bottles.15

John David Rhodes, calling this a moment of ‘intense pictorial abstraction,’ finds another layer in the scene’s commentary on modern industry:

The demijohns are particularly interesting here insofar as they metonymise the traditional commodities (oil and wine) associated with Italian agricultural labour and commerce. These workers are being plucked from an artisanal and ancient mode of work and trading in order to be inserted into the dynamised and more radically globalised world (oil) economy. […] [The demijohns’] deployment as material for stylistic expression, or articulation, asks that they be thought in terms of relation and difference. Style connects them […], but they are also media of connection – through trade […] and other modes of consumption.16

What I want to draw out from the two passages just quoted are a cluster of familiar ideas: a pictorial (and colour-coded) abstraction taking over the image, in a quasi-threatening manner; cinematic style foregrounded beyond reason, beyond the normal grammar by which stories are told, but for the sake of communicating something about the character’s state of mind; a sense of relation and difference between the old world and the new, between one kind of oil and another, between the gleaming utopia and the grey fruit-seller; and above all, the centrality of ‘media of connection,’ the blurring-together of the modes (professional and personal) by which we relate to each other.

The overwhelming copiousness of the demijohns is perhaps the most crucial factor here. It undercuts the sense that they are products of skilled artisans, and makes them seem like they must have been created by machines, or at least by a highly mechanised, dehumanising industrial process. Dalle Vacche also cites Andy Warhol’s declaration:

I paint cans of soup because I want to be a machine. ... It doesn’t matter who did it. Everybody thinks the same, and every year that goes by we resemble each other more and more.17

In Red Desert, art belongs to the machines. It is the very proliferation of these identical objects that makes them beautiful: a single demijohn, or just a dozen of them, or a large number of visibly different ones, would not amaze us in the same way.

The ground of the courtyard is covered with straw, and straw has been carefully placed between the demijohns to cushion them in their un-wickered state. In leaving the warehouse, we have been transported to a world where all materials and surfaces are either soft or luminous, a sort of cloud-land made of hay, celestial bubbles, and of course the ever-present fog. The demijohns, though associated with traditional Italian crafts, create a futuristic effect when stacked up like this. Their soothing blue colour also echoes the predominant colour in the warehouse, and this final shot in the briefing sequence hits us like a breath of fresh air. Dalle Vacche noted the sense of menace in this scene, the feeling that we are surrounded by ‘threatening, artificial creatures at the beginning of a new age,’ but through another lens, the blue orbs are pleasant and calming to look at.

Corrado strolls through this courtyard. Someone else has left just before him and we can see there are people still inside the warehouse. After the meeting, Corrado seems to be in the same mood as when we last saw him. He walks slowly and aimlessly, his left hand in his pocket. He hangs his head, glances around, kicks a small brown bottle out of his way, then kicks at the air or the hay a few times. Finally, he comes to a stop and looks out into the fog as we cut to the next scene.

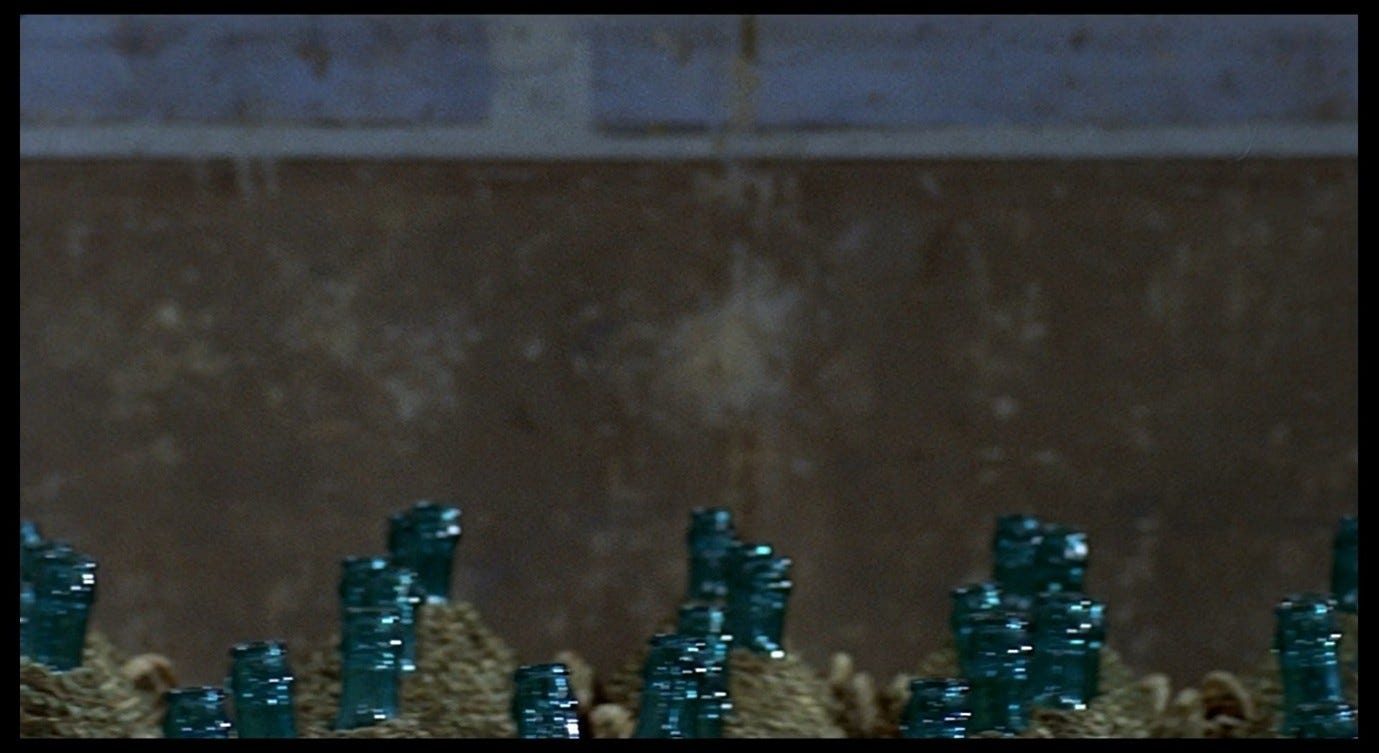

The imagery in this shot is well aligned with Corrado’s mood. The blueness of the demijohns is suggestive of melancholy as well as calm, and their hollowness seems emblematic of vanity and emptiness. Placed this way up, the bottles also respond to their ‘headless’ counterparts in the earlier shot inside the warehouse: there, the bottlenecks seemed to be missing something, leaving the part of the frame empty where the heads should be (and where the heads of workers were at the start of the shot).

Here, we see nothing but heads. They are still so many empty vessels, but now it seems beside the point whether they will be filled or not; they are there to be empty and infinite. The same constellation of lights is reflected in each vessel, like little electronic eyes, so that we are also reminded of the disembodied eye (and glowing robot eyes) in Valerio’s bedroom. Finally, we may be aware that these reflected gleams are the film crew’s lights, illuminating the set for the benefit of the camera-eye. As the camera pans with Corrado’s movement, he appears to be surrounded by eyes that follow his progress.

Corrado looks small and insignificant among the blue orbs, unable to comprehend or otherwise engage with them. They do not precisely ‘stand for’ the project he is working towards, but they help to underline his growing sense of alienation from that project. There is a progression from the oggetti that surrounded him inside the warehouse to those that surround him outside the warehouse: these are the things he has attorno, the things that define him. They seem to be accumulating indefinitely, for no apparent reason, like the blue line that follows itself around a white wall forever. They have a kind of beauty but it belongs to them (and to the machines), not to us. All we can do is be impressed – perhaps frightened, perhaps numbed – and continue our work.

The men in the warehouse, if they have until now been working in a glassware factory, can easily be transplanted to the Patagonia project because their skills are transferable. Corrado’s work too seems distinctly transferable, consisting mostly of getting the necessary personnel and equipment in place so that a new set of machines can begin producing a new stream of products – petrochemical products rather than blue demijohns, but at this moment the difference feels arbitrary.

We leave Corrado on this melancholy note, foreshadowing his final appearance in the film, when we will see him slouch across another (emptier) space having not quite confronted the existential horror before him. His sedated, repressed attitude stands in contrast to Giuliana’s, which is intensely emotive. Corrado ambles through the industrial landscape, squinting quizzically at it, asking his question, ‘How should I live?’ He wonders whether he is going through the right motions but he keeps going through them anyway. Giuliana stares, wide-eyed, at the same landscape, and asks, ‘What should I look at?’, which is also like asking ‘What am I looking at?’ Corrado’s gaze, drifting over the workers and the objects in the warehouse, does not really want to see or understand these things, whereas Giuliana’s seems compelled to see and understand everything.

Next: Part 30, The disintegration of values.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 483

Pasolini, Pier Paolo, ‘The Cinema of Poetry’, in Heretical Empiricism, ed. Louise K. Barnett, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise K. Barnett, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), pp. 167-186; pp. 179-180. Italian text from Pasolini, ‘Il cinema di poesia’, Scraps From the Loft (11 September, 2020).

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; p. 284

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 291. Taylor translates ‘Je regarde tout cela avec beaucoup d’envie’ as ‘I feel very envious of such people,’ but I have opted for a more literal translation. For the original French text, see Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘La nuit, l’éclipse, l’aurore’, in Cahiers du Cinéma 160 (November 1964), pp. 8-17; p. 15.

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 293. Taylor translates ‘on peut’ as ‘have to,’ but I think Antonioni is talking about themes which can now be treated in the post-post-war context. Taylor also leaves ‘aujourd’hui’ un-translated.

Pasolini, Pier Paolo, ‘The Cinema of Poetry’, in Heretical Empiricism, ed. Louise K. Barnett, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise K. Barnett, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), pp. 167-186; p. 178. Italian text from Pasolini, ‘Il cinema di poesia’, Scraps From the Loft (11 September, 2020).

Pasolini, Pier Paolo, ‘The Cinema of Poetry’, in Heretical Empiricism, ed. Louise K. Barnett, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise K. Barnett, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), pp. 167-186; p. 174

Bondavalli, Simona, Fictions of Youth: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Adolescence, Fascisms (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), p. 177

Pasolini, Pier Paolo, Theorem, trans. Stuart Hood (New York: New York Review Books, 1992), p. 169

Pasolini, Pier Paolo, Theorem, trans. Stuart Hood (New York: New York Review Books, 1992), pp. 176-177. Italian text from Pasolini, Teorema (Milano: Garzanti, 1968), Kindle edition, loc. 2284.

Bondavalli, Simona, Fictions of Youth: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Adolescence, Fascisms (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), p. 169

Bondavalli, Simona, Fictions of Youth: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Adolescence, Fascisms (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), p. 178

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 293

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The Color of Jealousy’ (trans. Andrew Taylor), in Unfinished Business: Screenplays, Scenarios and Ideas, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 117-172; pp. 126-127

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 66

Rhodes, John David, ‘Antonioni and the Development of Style’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 276-300; p. 290

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 66