Everything That Happens in Red Desert (47)

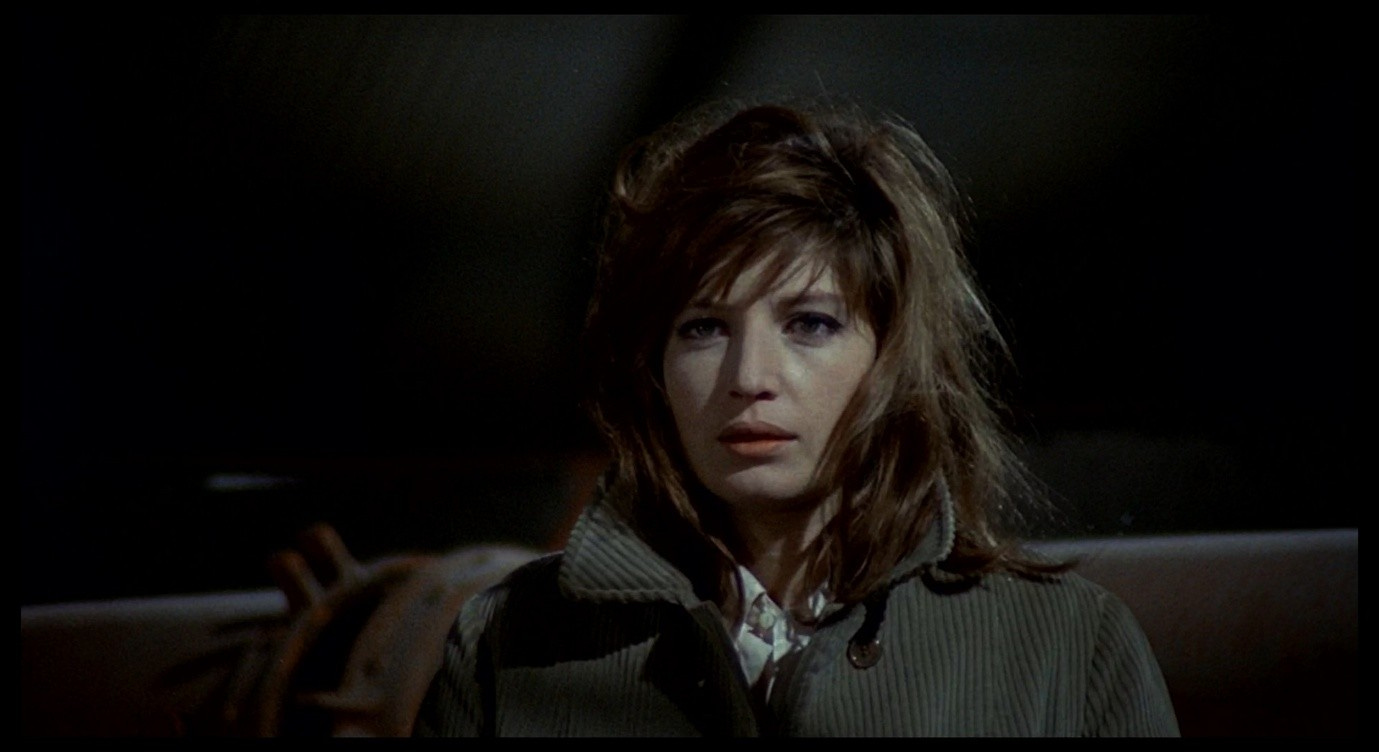

Giuliana's explanation

After her embarrassing quasi-conversation with the Turkish sailor, Giuliana descends back down the ramp. ‘I don’t understand,’ says the sailor, in Turkish. The screenplay suggests multiple reasons for her retreat:

As if the stranger could understand her, she runs for cover to minimise the significance of her question. […] The penetrating gaze [sguardo penetrante] of the Turk, trying to catch the meaning of her words or lip-movements, suddenly scares her. She steps back.1

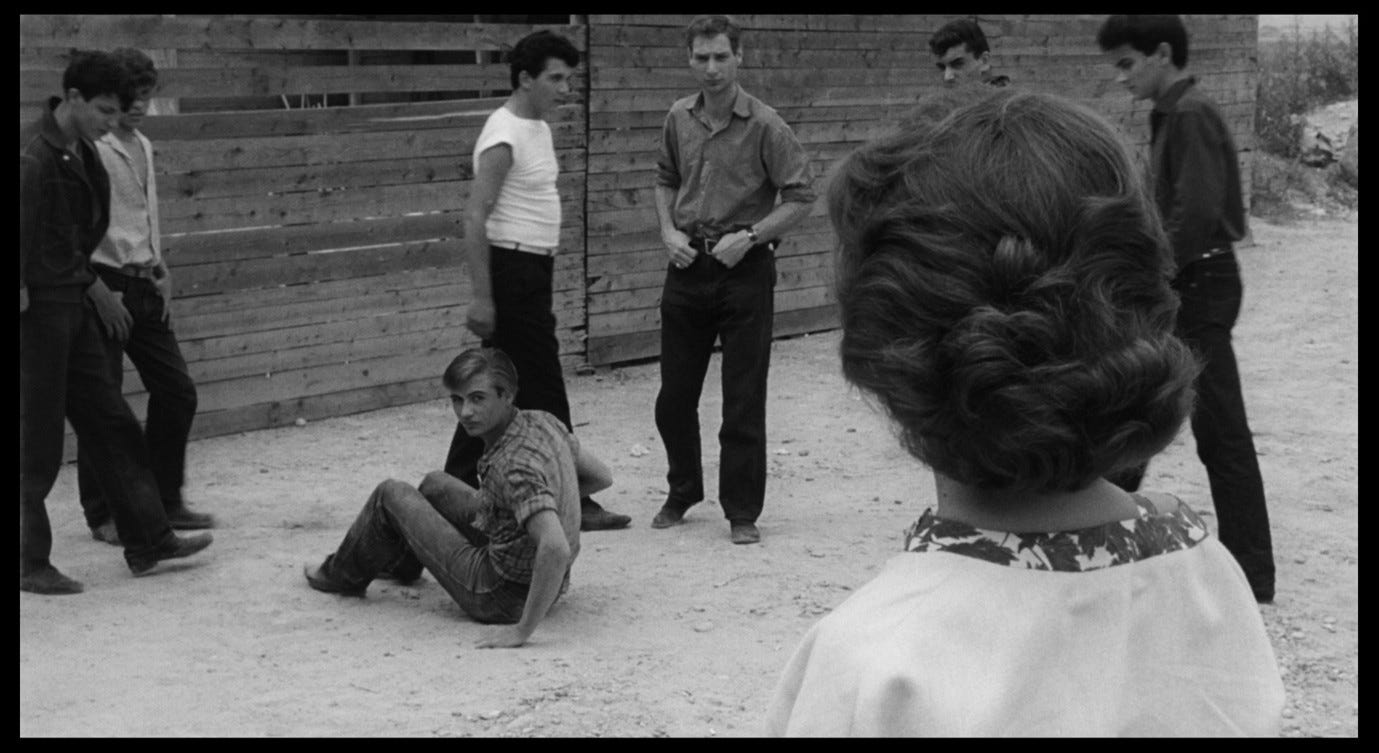

She has asked whether the ship takes passengers, and is afraid the sailor may actually have understood this question. This is also why his sguardo penetrante frightens her: it is specifically his attempt to decipher her meaning that makes her turn away. Strangers in Antonioni films often seem to pose a vague threat that is never fulfilled. Think of Rosina encountering the patients from the mental hospital in Il grido, Claudia surrounded by the ogling men in L’avventura, or Lidia’s encounter with the violent street gang in La notte.

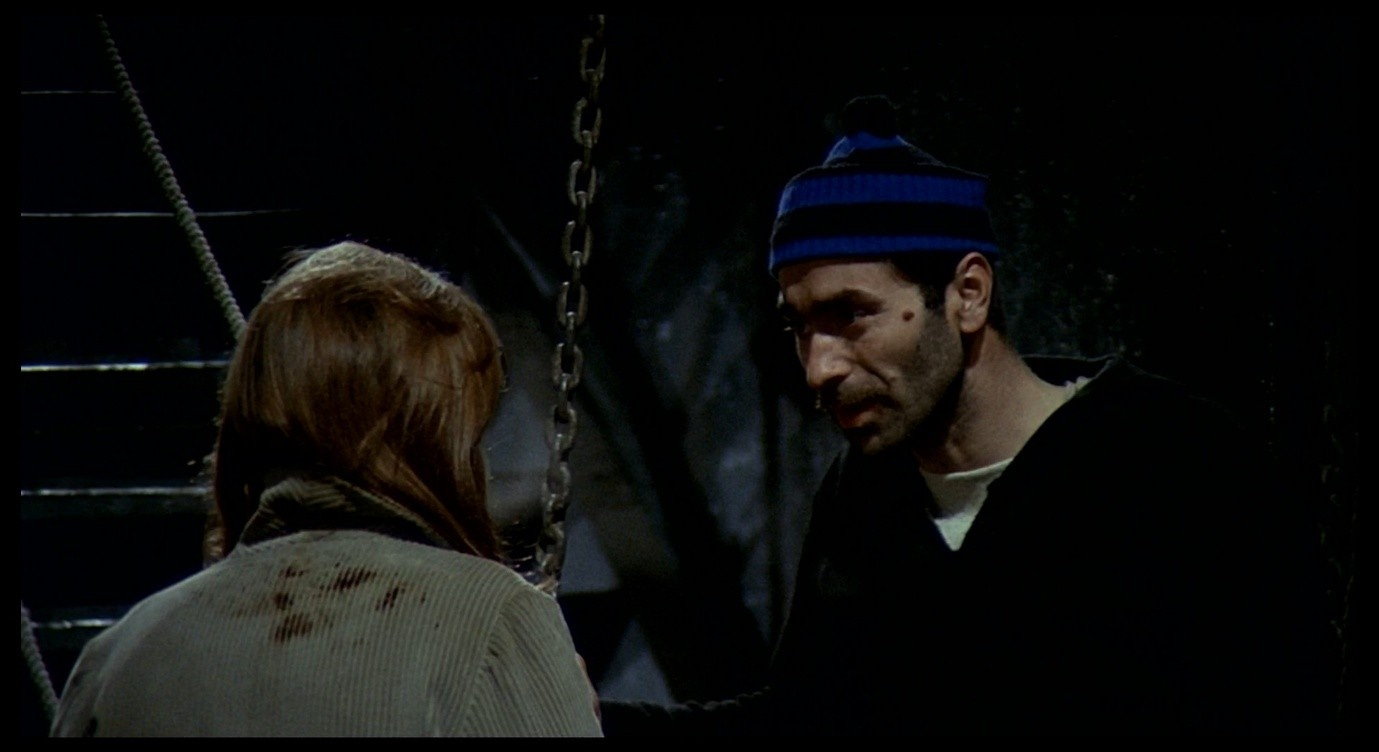

The shipyard scene in Red Desert takes place in the middle of the night, and when the sailor follows Giuliana down the gangway, there is a slight hint of danger.

But as the screenplay indicates, this fear is more about ‘being seen’ than being physically attacked. In all three of the examples just cited, or in the encounter with the fruit vendor earlier in Red Desert, or indeed in Lo sguardo di Michelangelo (discussed in Part 14), we get a powerful sense of that sguardo penetrante that reveals something extraordinary and terrifying, that penetrates in the sense of accessing another’s interior life, but that is by the same token invasive and alienating.

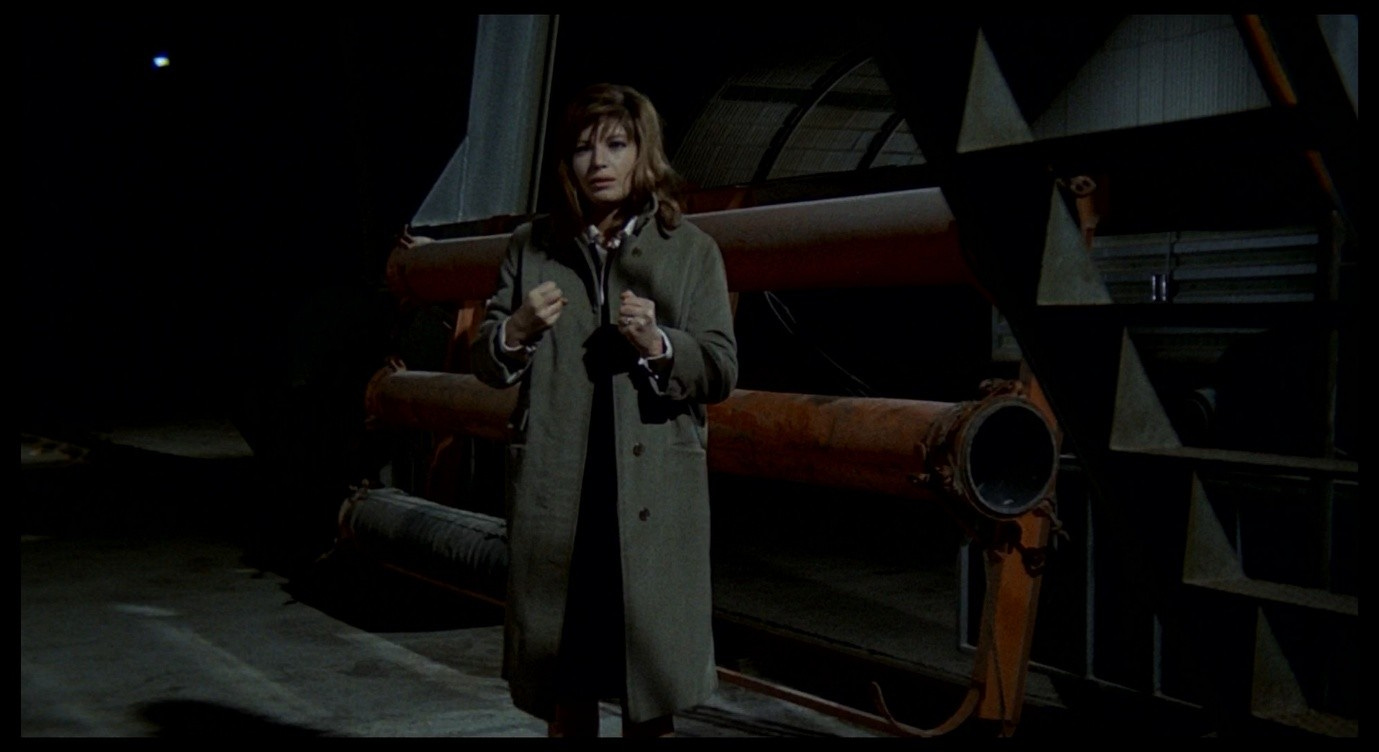

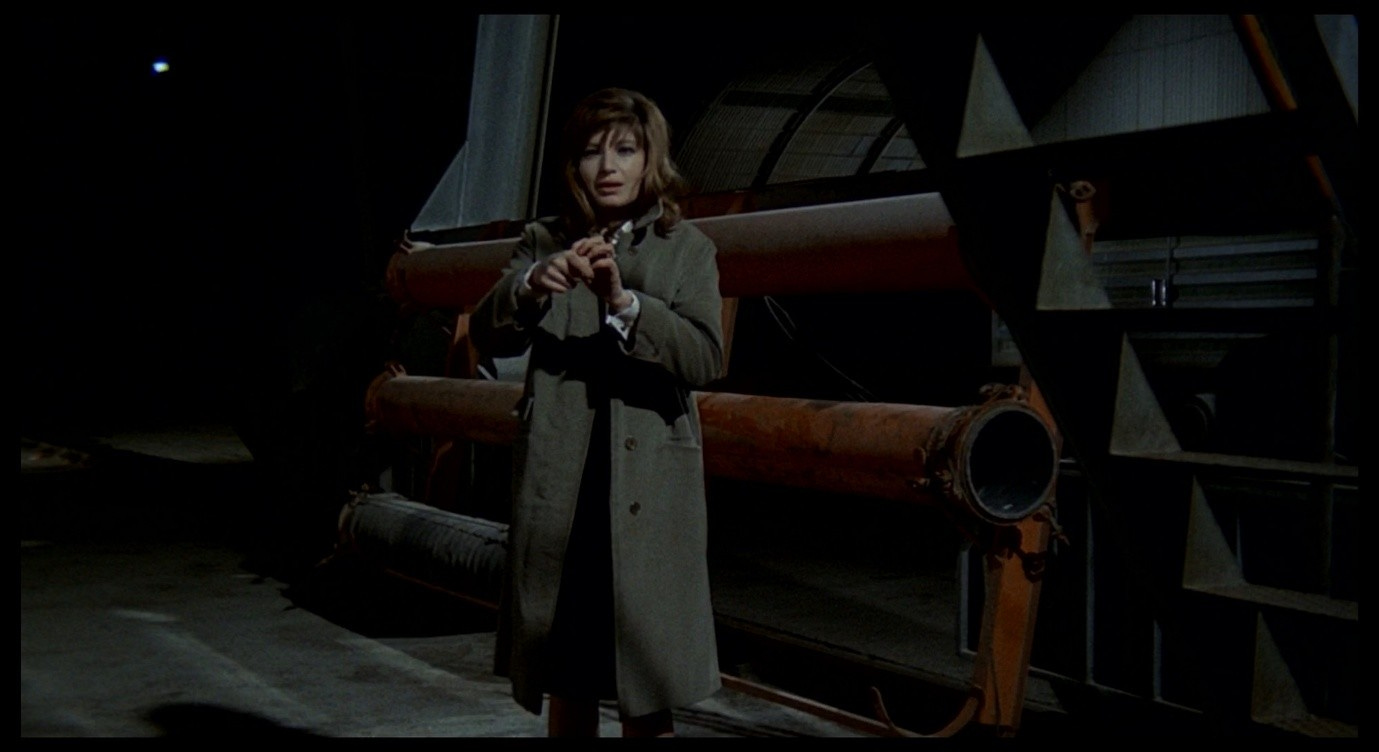

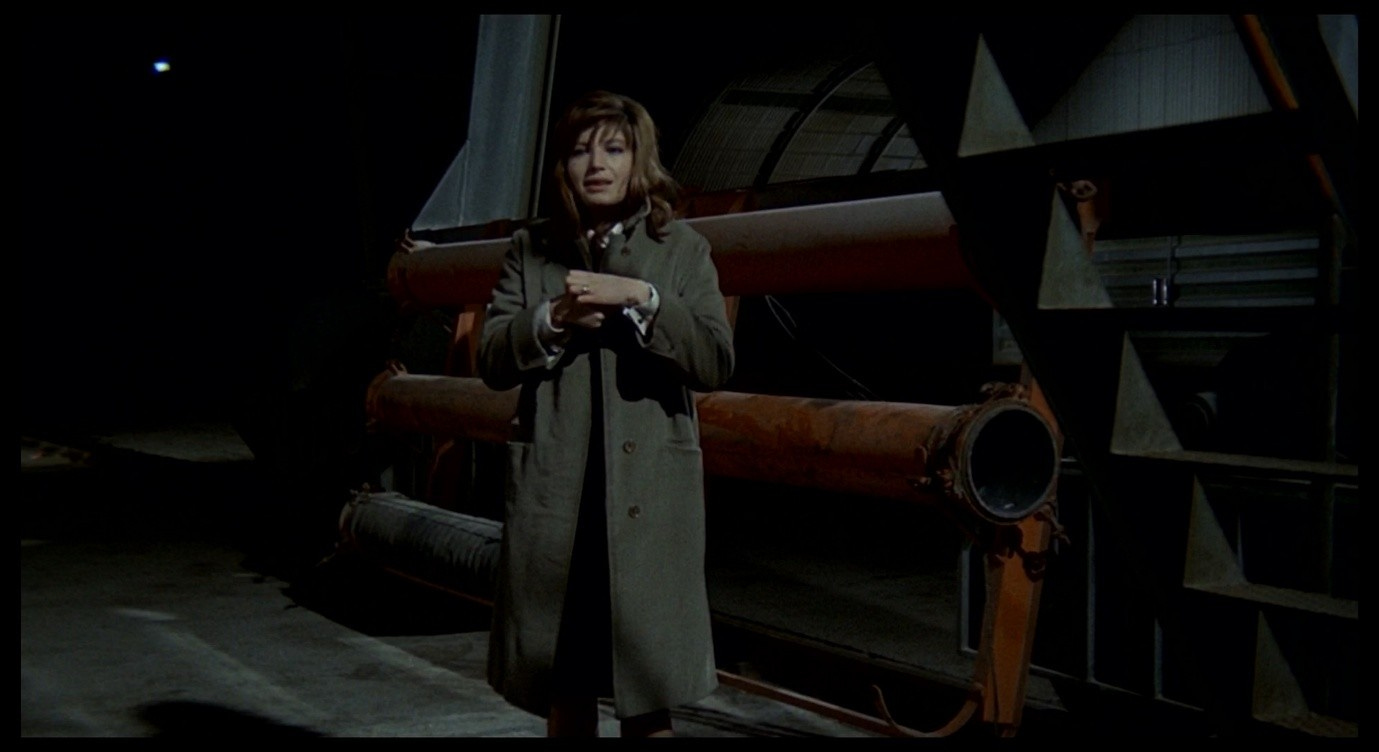

Giuliana flees from the danger of being understood, the sailor reciprocates by saying that he does not understand, and a distance opens up between them. In two successive shots, she walks past a large metal structure that blurrily dominates the foreground of the long-lens images.

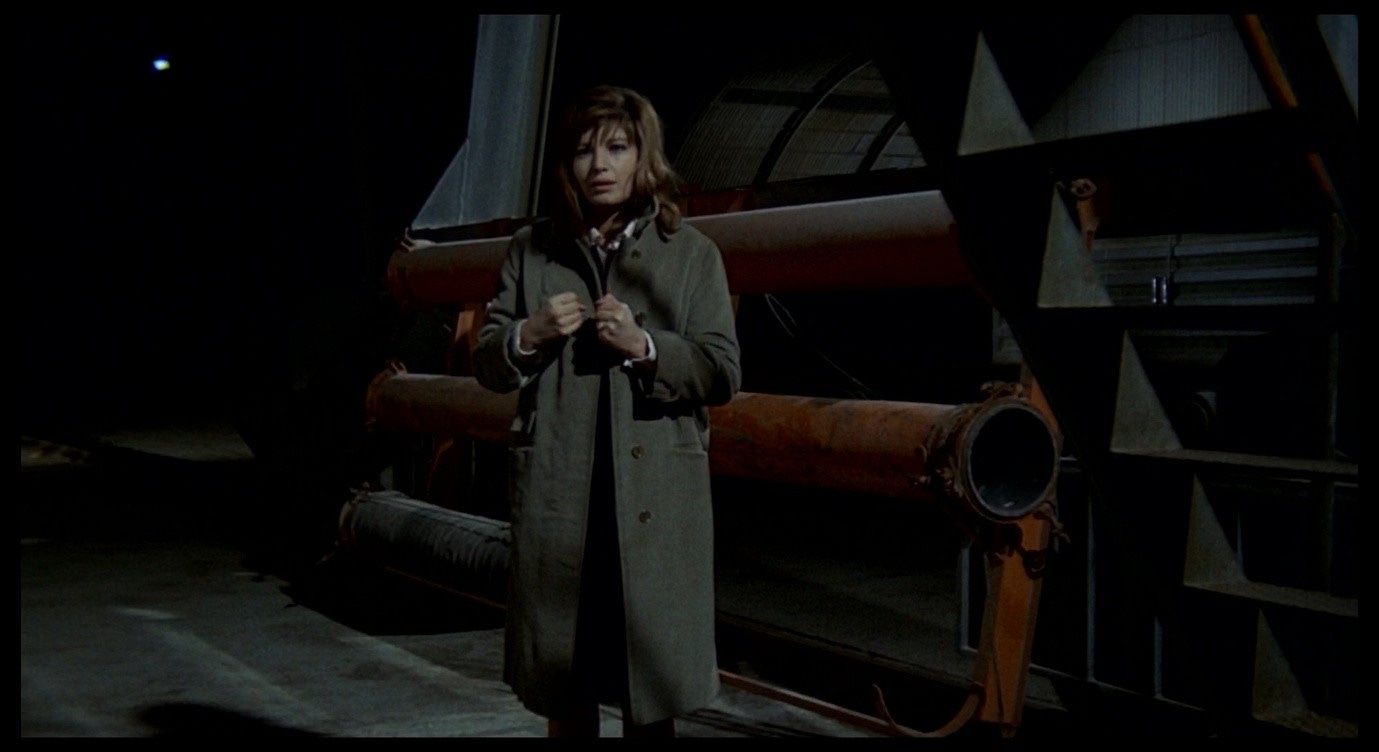

The screenplay specifies that this machinery contains ‘the motors for loading and unloading ships,’2 appropriately enough for this moment that hinges on Giuliana’s decision whether to join the rest of the cargo or stay on land. She now stands on the other side of this contraption, positioning herself firmly on land and away from the transitional space of the gangway. She spends a few seconds finding the right position from which to speak, distancing herself from the sailor’s gaze and perhaps also from what he represents (a peripatetic life, un-moored from land, home, human connections, and native language).

Just as she was afraid of looking at the ocean because she felt it would dissolve her connection to the land (see Part 22), so she seems afraid of the dissolution she would experience if the sailor continued to stare back at her as he has been doing. It is significant that there are no reverse-shots of his reaction during Giuliana’s speech, as there were none of Mario in the encounter at Medicina (see Part 17), and for similar reasons. In a sense, Giuliana is not talking to this sailor and does not want him to hear or understand her. In protecting herself from him, she also isolates herself, and the speech she now gives will expand on this lonely condition.

The idea that her question (‘Does this ship take people?’) may have been understood is embarrassing to Giuliana, in part because it reflects her desire to leave her family. She begins her speech by referring to these family ties, and by trying to clarify what kind of separation is at stake here:

I cannot decide, because I am not a single woman [donna sola]. However [Per quanto], at times, it’s as if…separated [è come…separata]. No, not from my husband, no. The bodies are…separated. If you prick me, you don’t suffer, eh?

The phrase donna sola (as in Pavese’s Tra donne sole) can mean ‘single woman’, ‘woman alone’, ‘woman only’, and ‘lonely woman’, and this part of Giuliana’s speech is infused with a sense of how these meanings co-exist. She begins with a denial of agency: it is not simply that she cannot board the ship, but that she cannot make a decision at all. The decision has been made for her, because she is not sola, she is connected to other people. It is not so much a question of her familial responsibilities as of her lack of autonomy. In the previous scene, she complained that the doctors mi parlano di me, or ‘talk to me about myself,’ but then her problems would afflict her when she was sola. Who Giuliana is, and what she does, is dictated by other people, by the surrounding structures over which she has no control. The result is that she has no power to act of her own accord.

On the other hand (per quanto) she is alone in the sense of being disconnected. The phrase è come separata removes any reference to herself: she does not say, ‘I feel separated’ or ‘It’s like being separated.’ It is as if she were describing another person or thing, not herself. In the clinic, she was required to regard herself as another person, to whom she had to explain who ‘she’ was. There is a continuity between that predicament and the present speech, in which Giuliana cannot function or make decisions da sola (by herself) and describes a feeling of profound and un-specified separateness, from her ‘self’ as well as from others.

The non-specific phrasing of è come separata prompts Giuliana to clarify what she does not mean: she is not saying, ‘It’s as if I were divorced from my husband.’ Her near-escape on the ship is not specifically an attempt to leave Ugo, but a more symbolic gesture that expresses her alienation from everyone. In explaining this, Giuliana focuses on the concept of bodies, and provides an illustrative example. The line, ‘If you prick me, you don’t suffer,’ alludes ironically to Shylock’s protest, ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’,3 which invoked a universal bodily experience. What Giuliana describes is just as universal, but closer to Edgar Allan Poe’s grim meditation at the start of ‘The Premature Burial’: ‘That the ghastly extremes of agony are endured by man the unit, and never by man the mass – for this let us thank a merciful God!’4 True empathy, in other words, is not encoded in the human body, as it is not literally possible to share feelings. As T. S. Eliot said in The Waste Land, ‘We think of the key, each in his prison / Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison.’5

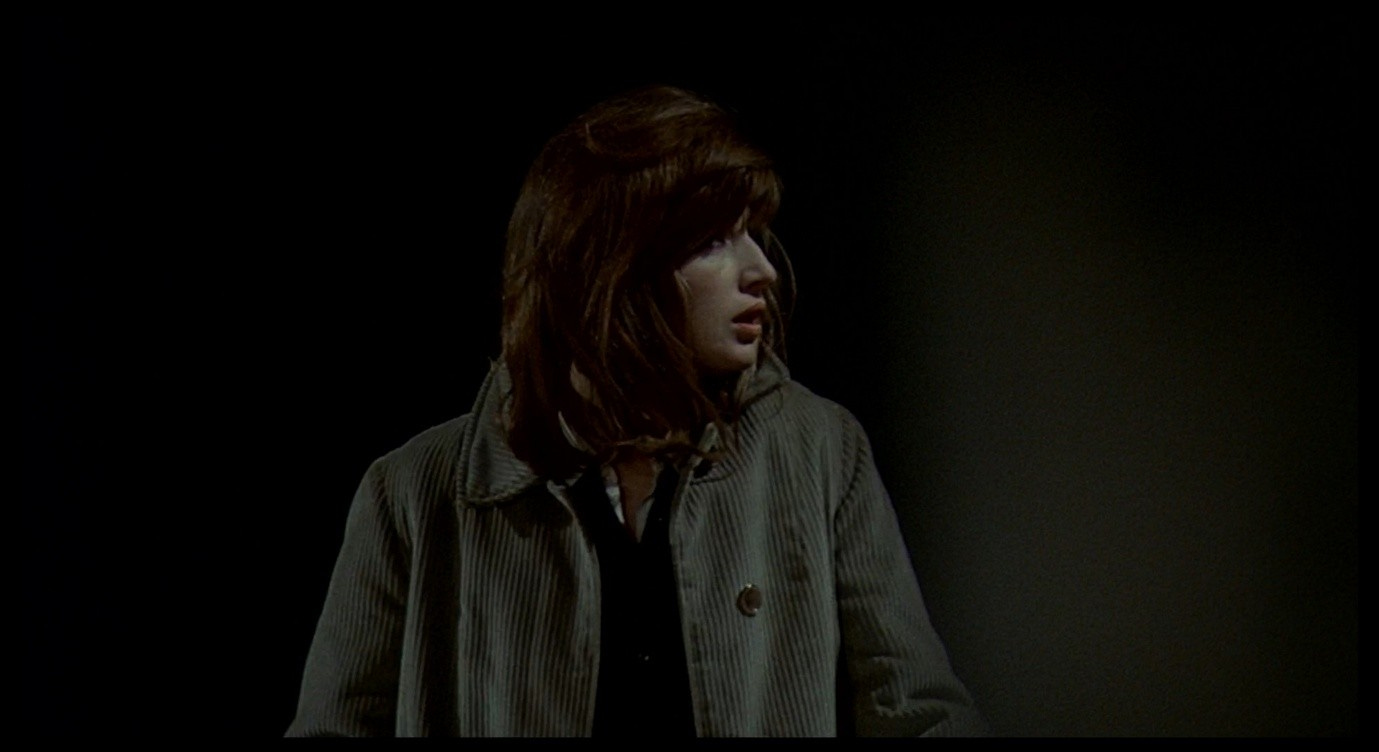

Until she says ‘If you prick me,’ we have been watching Giuliana give her speech in a medium close-up with no clear view of her surroundings, but now we cut to a wide shot and see the shadowy docklands behind her.

Suspended on a metal rack are two long red pipes and, below them, one corrugated grey pipe that is half their length. Like the shapes in that abstract painting in Corrado’s hotel room, the pipes are parallel to each other but not touching, suspended in a state of separation that defies their purpose.

These pipes, in their detached and/or shortened states, are incapable of transmitting or even containing the liquids or gases they were designed for. To the right, a flight of metal stairs appears to lead nowhere (but presumably gives access to the loading equipment), and in the deep background there is an empty-looking hangar and a pitch-black void. Like the white wall Giuliana stood in front of when she talked about reinserting herself into reality, this backdrop is powerfully evocative of the emotional state she is describing. There she seemed alone and isolated in a nebulous void, here she seems alone and isolated among dis-connected objects.

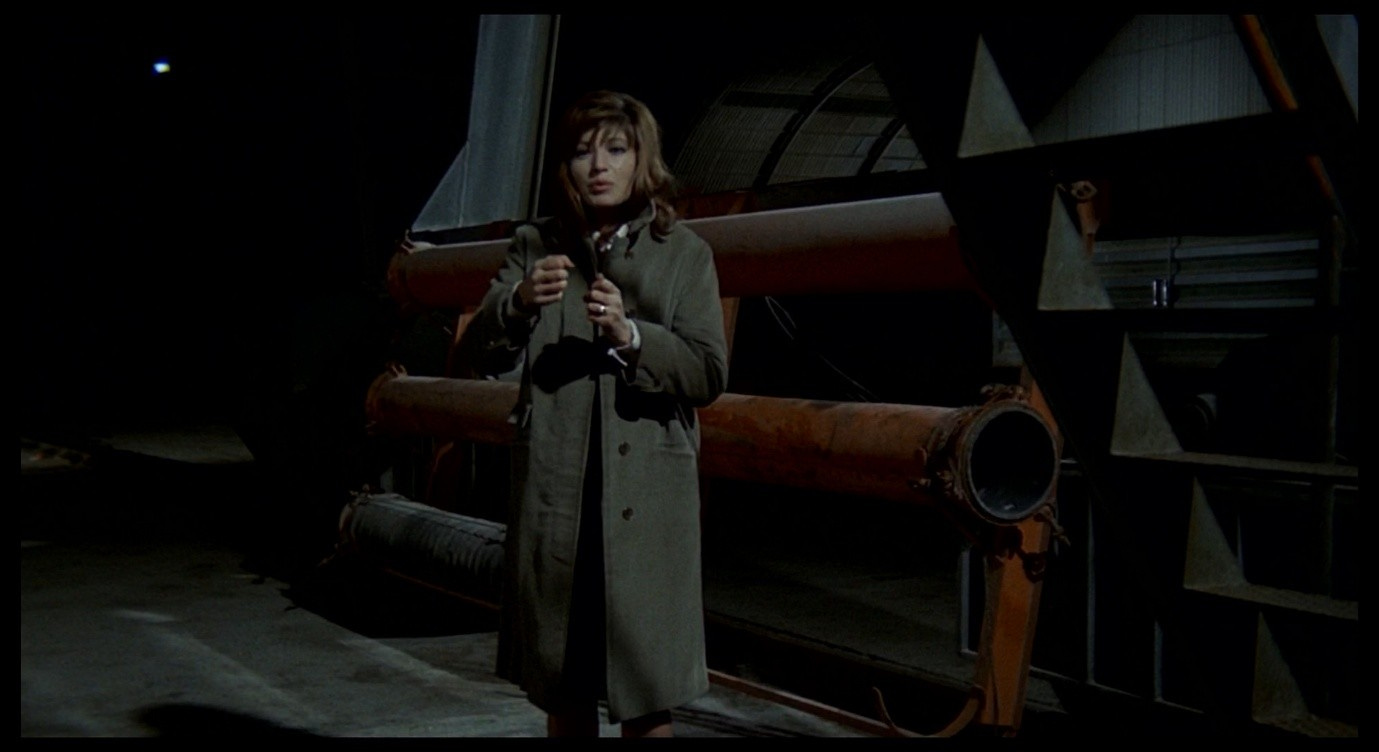

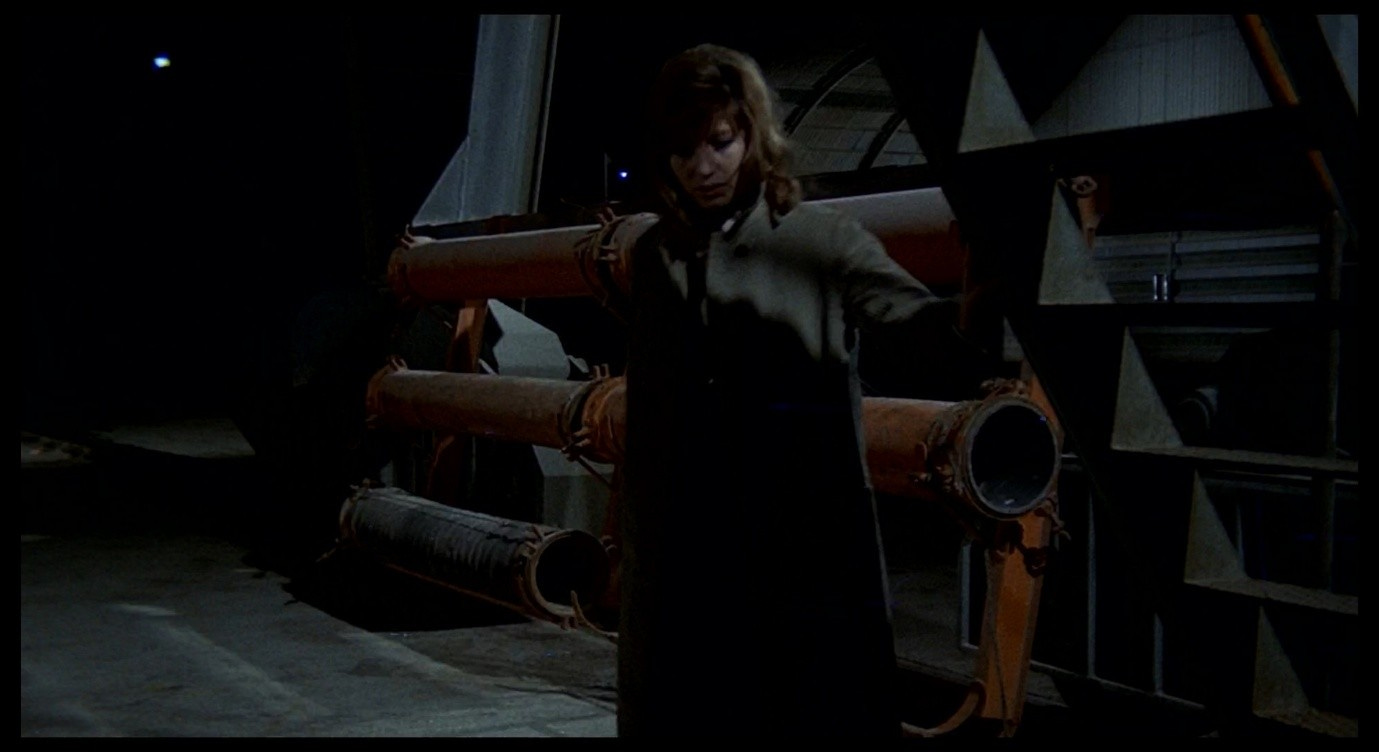

Giuliana points at the sailor when she says ‘If you prick me,’ then scratches one of her hands with the fingers of the other hand.

Earlier, I argued that she is not really talking to the sailor here, and that she does not really want him to understand her, but these gestures would seem to belie this argument. Giuliana goes out of her way to engage the sailor, to act out her words so as to overcome the language barrier, and to rhetorically invite his agreement with her ‘Eh?’ at the end of the sentence.

But of course, he cannot possibly know what she is saying. This very communication failure proves her point. If he pricked her, he would not suffer, and whatever idea she has in her head cannot be transferred into his. This is why she is saying these things to this specific person. Giuliana is sharing her revelation with someone who cannot share it, because this is precisely the kind of insurmountable separation she is trying to describe.

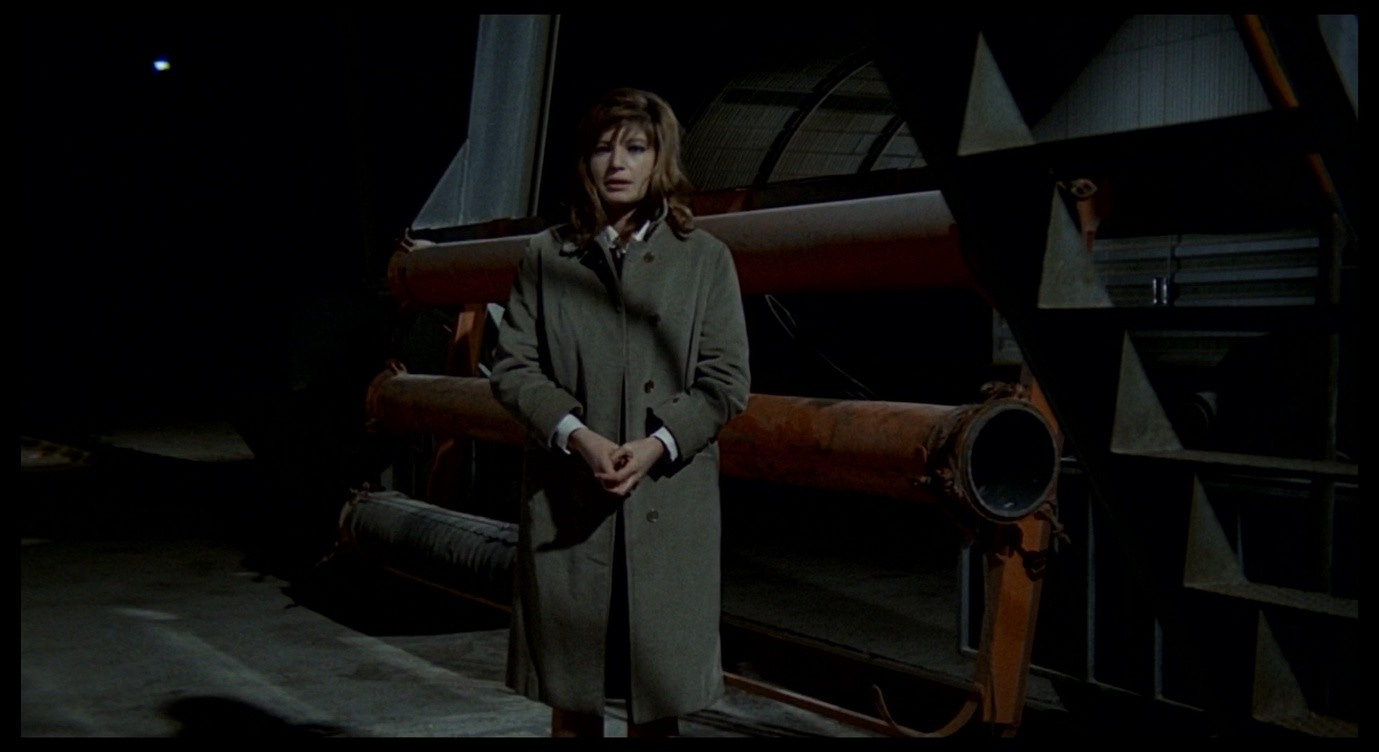

The cut to a wide shot reflects Giuliana’s shift into an explanatory mode, where she stands back from her own thoughts, gains some perspective on them, and considers how to lend them more clarity. This is like standing outside herself to explain who ‘she’ is, so naturally Giuliana experiences a moment of disorientation. After illustrating her point with the hand-scratching gesture, she asks, ‘What was I saying?’, and there is an uncomfortably long pause.

She has put herself at a distance from her own speech, losing the thread, and providing yet another illustration of her point. If he pricks her, he won’t suffer; if she has an idea in her head, he cannot share it; if she tries to see things from his point of view, she loses track of her own. When she remembers what she was about to say (‘Ah yes…’), we cut back to the medium close-up.

That fleeting sense of perspective, that potential for connecting with the world around her, is lost again – the world around her is visibly incapable of being connected with – and we return to a focus on Giuliana alone. Now we may notice the dark gap between the two sections of piping behind her, not visible in the wide shot. The sections have been brought close enough together to create that small shadowy chasm, without actually being joined up.

If Giuliana is hurt and suffering, this experience is confined to her own mind and body, and within these confines she will have to find a resolution to her problems. When she finishes speaking, we will cut back to the ‘If you prick me’ wide shot, but only to see her apologetically shuffle out of frame.

The conclusion she arrives at will be simple and self-centred, a credo that by definition can only be meaningful to her, while to anyone else it will appear empty and tautological. At the end of this scene she will appear lost, directionless, stumbling away from the sailor as he says, ‘Lady, if you don’t feel well, let me help you. Why don’t you go home? It’s very cold out here. I don’t understand, I don’t understand.’ Giuliana is aware of how stupid or crazy she might appear to this stranger, and somewhat ashamed of this as she haltingly exits the scene. But from our privileged perspective, we may be able to appreciate the significance of her statement, ‘Everything that happens to me is my life.’

William Arrowsmith, citing the ‘think of the key’ passage from The Waste Land, relates it to the specific kinds of ‘sick Eros’ that Antonioni portrays:

The individual is driven violently toward transcendence by the need to obliterate all barriers in compulsive or serial intimacy. […] The danger […] is that the individual may lose himself in a solitude or solipsism like Ugolino’s prison as described by T.S. Eliot. […] Antonioni’s characters believe that the prison can be obliterated through erotic transference. On the one side, loneliness and self-incarceration; on the other, deliberate, obsessive immersion (another incarceration), in the destructive element of another’s being, in the self-extinction of an Eros that aims at self-extinction, or that confuses self-extinction with otherness. The dangers of this destructive element are very real, especially for Antonioni’s women; Red Desert is transparently an effort to deal with the neurosis, even pathology, of this Eros.6

This formulation emphasises agency: the individual pursues sexual encounters with a transcendent goal in mind, but either makes herself lonely through promiscuity or annihilates herself through over-immersion in a single other. Thus Giuliana, in the wake of the hotel room scene, could be read as grappling with the loneliness attendant on becoming an ‘unfaithful wife’ and/or with the sense of self-annihilation she experienced when her body mingled with Corrado’s and the entire room turned pink. One way or another, she is afflicted with some form of erotic pathology which has made her go astray, and she must try to ‘deal with this neurosis.’

Later, Arrowsmith says of the ‘bodies are separate’ speech:

Here, stated with the compelling slowness of conscious realization and pained understanding, is the adult recognition of separateness and loneliness, which divides child from woman, neurotic from healthy.7

There is a moralistic element to this reading, and a certainty about the realities to be ‘realised, understood, and recognised,’ that are alien to what I find in Red Desert. Giuliana’s speech to the sailor is demonstrably concerned with what she ‘should’ do and think, but these prescriptions are shot through with uncertainty. If Dante’s Ugolino is cruelly imprisoned as a result of his own treachery, Eliot’s re-working of the prison motif suggests a more universal condition, and one that we may not have inflicted on ourselves. Someone has locked us in this cell: thinking of the key ‘confirms a prison,’ it does not create that prison; our fantasy of openness and connection is like an outline drawn around our closed and alienated self. Giuliana does not make communication impossible between herself and the sailor, it simply is impossible, and she describes their relationship in such a way as to confirm that impossibility. This is why it is so important to acknowledge what she says about her lack of agency. Paradoxically, it is her insight into this lack of agency that accounts for the richness and profundity of what she says in this scene.

In the end-notes to The Waste Land, Eliot links the ‘think of the key’ passage not only to Dante but also to this passage from F. H. Bradley’s Appearance and Reality:

My external sensations are no less private to my self than are my thoughts or my feelings. In either case my experience falls within my own circle, a circle closed on the outside; and, with all its elements alike, every sphere is opaque to the others which surround it…. In brief, regarded as an existence which appears in a soul, the whole world for each is peculiar and private to that soul.8

The phrasing here reminds me of Secrets of a Soul and its recreations of external reality in the white-bordered interior world revealed by psychoanalysis (see Part 36). It is not only the thoughts and emotions that remain incommunicable, but even the physical sensations: how it feels to touch, or to be pricked. Bradley’s phrase, ‘the whole world for each,’ is something like what Giuliana refers to when she says, ‘Everything that happens to me is my life,’ but there is another source-text for this line that is more radically unsettling and Antonioni-esque.

A note in the Antonioni Archive (made during the filming of Red Desert) highlights a specific passage in Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, volume 2, page 270 onwards.9 In the Italian translation from 1958, on those pages, we find the following passage (spoken by Ulrich to his sister):

When I remember as far back as I can, I’d say that there was hardly any separation between inside and outside. When I crawled toward something, it came on wings to meet me; when something important happened, the excitement was not just in us, but the things themselves came to a boil. I won’t claim that we were happier then than we were later on. After all, we hadn’t yet taken charge of ourselves [non possedevamo ancora noi stessi]. In fact, we didn’t really yet exist; our personal condition was not yet separated from the world’s. It sounds strange, but it’s true: our feelings [i nostri sentimenti], our desires [le nostre volizioni], our very selves [il nostro io], were not yet quite inside ourselves. What’s even stranger is that I might as easily say: they were not yet quite taken away from us. If you should sometime happen to ask yourself today, when you think you’re entirely in possession of yourself, who you really are, you will discover that you always see yourself from the outside, as an object. […] No matter how intensely you try to look at yourself, you may at most find out something about the outside, but you’ll never get inside yourself [riescirai tutt’al piú a scoprirti, mai però a entrarti dentro]. Whatever you do, you remain outside yourself. […] It’s true that as adults we’ve made up for this by being able to think at any time that ‘I am [Io sono]’ – if you think that’s fun. You see a car, and somehow in a shadowy way you also see: ‘I am seeing a car.’ You’re in love, or sad, and see that it’s you. But neither the car, nor your sadness, nor your love, nor even yourself, is quite fully there. Nothing is as completely there as it once was in childhood; everything you touch [tutto quello che tocchi], including your inmost self, is more or less congealed [assiderato] from the moment you have achieved your ‘personality,’ and what’s left is a ghostly hanging thread [una nebbia spettrale] of self-awareness and murky self-regard, wrapped up in a wholly external existence. What’s gone wrong? There’s a feeling that something might still be salvaged. Surely you can’t claim that a child’s experience is all that different from a man’s? I don’t know any real answer, even if there may be this or that idea about it [chi pensa questo e chi pensa quello]. But for a long time I’ve responded by having lost my love for this kind of ‘being myself’ and for this kind of world [ogni amore per questa specie di Io e per questa specie di mondo].10

The description of childhood as a time when one felt a sense of connection to one’s surroundings recalls Musil’s contemporary, Hermann Broch, who saw childhood in similar terms in The Sleepwalkers (see Part 32). Here too, connectedness is associated both with a kind of (lost) happiness and with a sense of solitude. Becoming an adult, one learns to say Io sono, but in the process one conjures a specie di Io that is separate from oneself. This self is il nostro io, but as soon as Ulrich speaks of this io being installed inside the person, he has to contradict himself by describing it as being separated from the person, along with that person’s sentimenti and volizioni. The latter term is more evocative of volition and agency than the English translation’s ‘desires’. Our will, the feelings that drive it, and the self to which will and feelings are ascribed, are all detached from us. Our sense (in childhood) of a unity between our feelings and those of the world around us becomes (in adulthood) a sense that everything we touch, including our self, is assiderato, frozen, like Ugolino in his lake of ice.

Ulrich’s phrase, tutto quello che tocchi, anticipates Giuliana’s tutto quello che mi capita (‘everything that happens to me’): he takes this positive action, the hand reaching out to touch something, and turns it into a revelation of helpless passivity; we think of the ice melting and thereby confirm the ice-prison. When you look in the mirror you can only scoprirti (‘discover yourself’), not entrarti dentro (‘enter yourself’), and likewise with all the other people and things around you. ‘Every sphere is opaque to the others which surround it,’ said Bradley, but for Musil each sphere is opaque even to itself, drifting helplessly beside this thing called io and its volizioni. Giuliana’s tutto quello che mi capita speaks to a similar kind of passivity. Like Ulrich, she has fallen out of love with the kind of io and the kind of mondo that she is supposed to feel invested in. Be oneself and love another, say the doctors; know who ‘you’ are and interact accordingly with the world ‘you’ inhabit; acquire that understanding which, Arrowsmith says, divides the neurotic from the healthy. But this division is not clear-cut in Antonioni’s world. Clara in La signora senza camelie would find herself compulsively repeating, ‘Sono io, io!’ There she was on the cinema screen, herself but also a personnage, a character; there she was married to Gianni, herself but also the wife he imagined her to be; not just io but io, io. In the end, neither self is really hers.

Both Clara and Giuliana also share Ulrich’s sense of uncertainty. Just as Musil’s novel refuses to end, Ulrich refuses to arrive at a conclusion, chi pensa questo e chi pensa quello. People can think this or think that, but he is a man without qualities. He is nothing, and thinks nothing, with any consistency. Corrado and the doctors have told Giuliana what she should (and should not) think, and now she will tell herself what she should and should not think, but this seemingly positive action – pensare – also seems to be something she discovers herself doing, watches herself doing, rather than a stable conclusion she arrives at. This passivity is frightening but strangely powerful, because it keeps us on the precipice, like Karin at the summit of the volcano in Stromboli, never knowing what will happen next and embracing that uncertainty. Resolved narratives, well-articulated beliefs, neuroses that have been dealt with, men with qualities, all seem to melt into one great nebbia spettrale by comparison.

Next: Part 48, Absurdity and the desert.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; pp. 495-496

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 496

Shakespeare, William, The Merchant of Venice, Act 3, Scene 1, ll. 63-64, The Folger Shakespeare

Poe, Edgar Allan, ‘The Premature Burial’, Project Gutenberg

Eliot, T. S., ‘The Waste Land’, in The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot (London: Faber, 2011), pp. 60-80; p. 74, ll. 414-415

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 72-73

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 94

Eliot, T. S., ‘The Waste Land’, in The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot (London: Faber, 2011), pp. 60-80; p. 80

‘Appunti per “Deserto rosso” [1963 - 1964]’, b. 8C/5, fasc. 41C, ArchivioAntonioni

Musil, Robert, The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), trans. Sophie Wilkins (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2017), pp. 1290-1291. Italian text from L’uomo senza qualità, trans. Anita Rho, vol. 2 (Torino: Einaudi, 1958), pp. 270-271; this specific volume is also listed in the Antonioni Archive.

Again, very interesting, and here you do begin to articulate the energy in openness! Again, again, I really don't think Ulrich ultimately thinks NOTHING, not Whatever, but possibly many things, with distinct strong opinions and some limits.... Think of it like relativity science, or Emergence. That reality is not to be understood using the old measurements of cause and effect or simple equations, but will need to be approached through more complex means, each element in a shifting relation to each other element, always shifting, but by no means anything or nothing//and not even everything. Just more than usually taken into consideration, and seen from more angles, in different new ways. Also...I have to tell you that Musil disdained Broch's Sleepwalkers and felt he was not up to the philosophizing he tried to do.