Everything That Happens in Red Desert (25)

The island of SAROM

This six-minute sequence takes place on the SAROM offshore oil rig, briefly referred to by Ugo in Max’s shack and known in Italian as the ‘steel island of SAROM.’ Like the earlier sequences outside and inside Ugo’s factory, and at the Medicina Radio Observatory, this one locates Giuliana among the edifices and paraphernalia of modern industry, and finds new ways to explore her emotional state through these juxtapositions. In talking to Corrado about his South American enterprise, Giuliana reflects on the connection between a person’s identity and their environment, and this in turn leads to the revelation that her ‘accident’ was a suicide attempt (which I will discuss in Part 26).

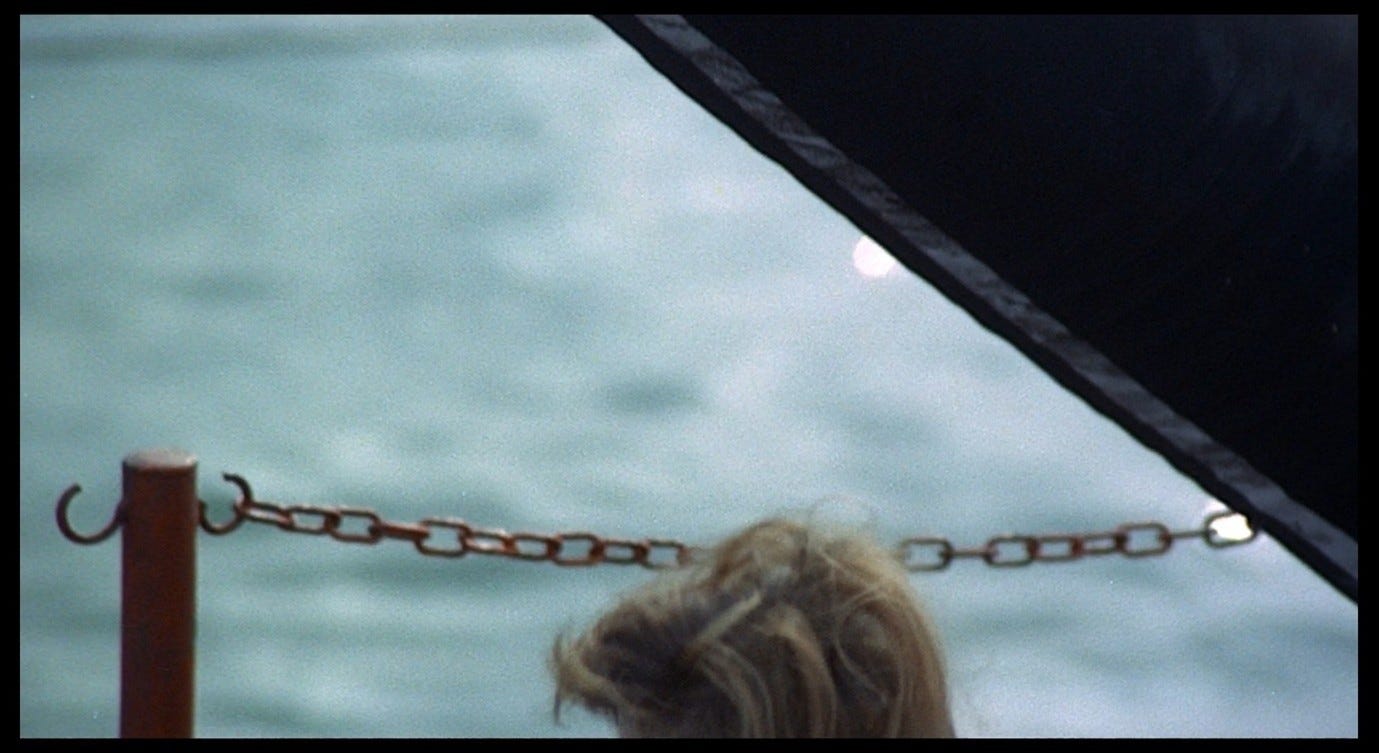

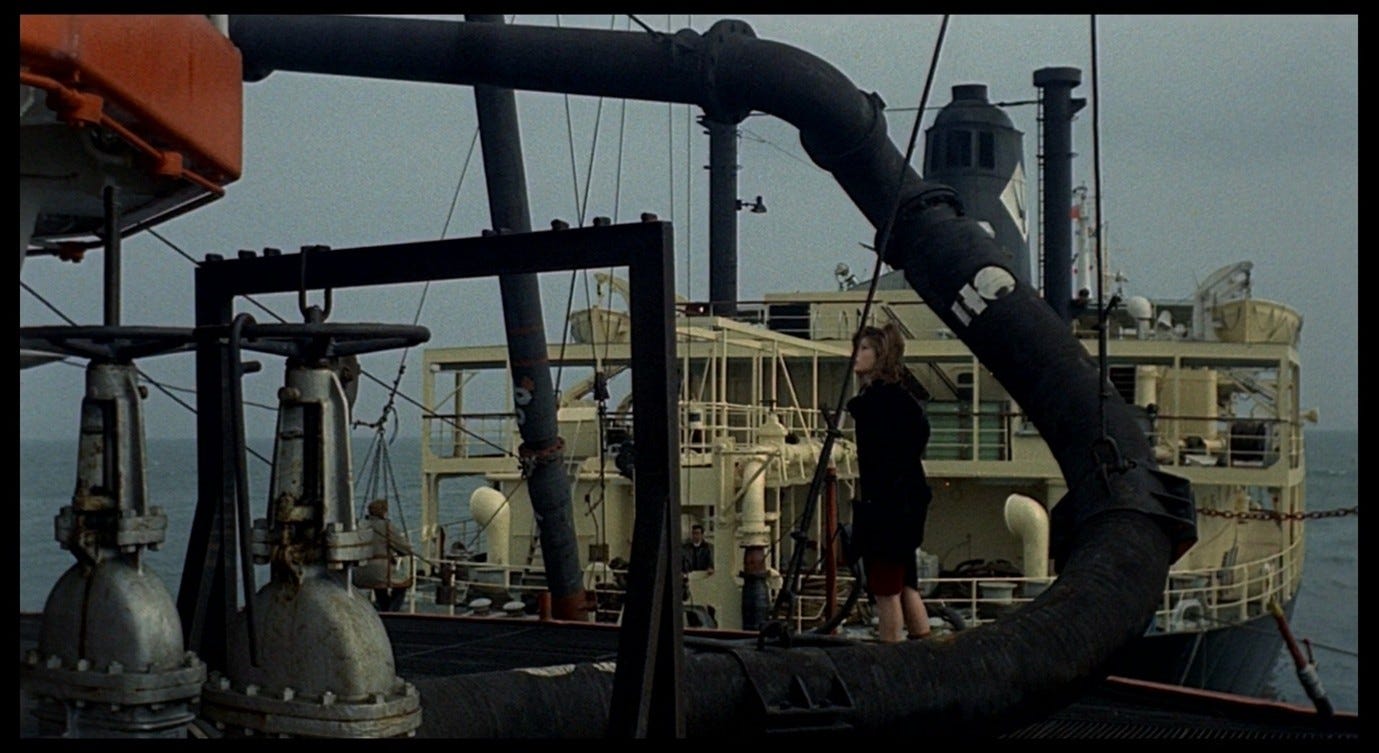

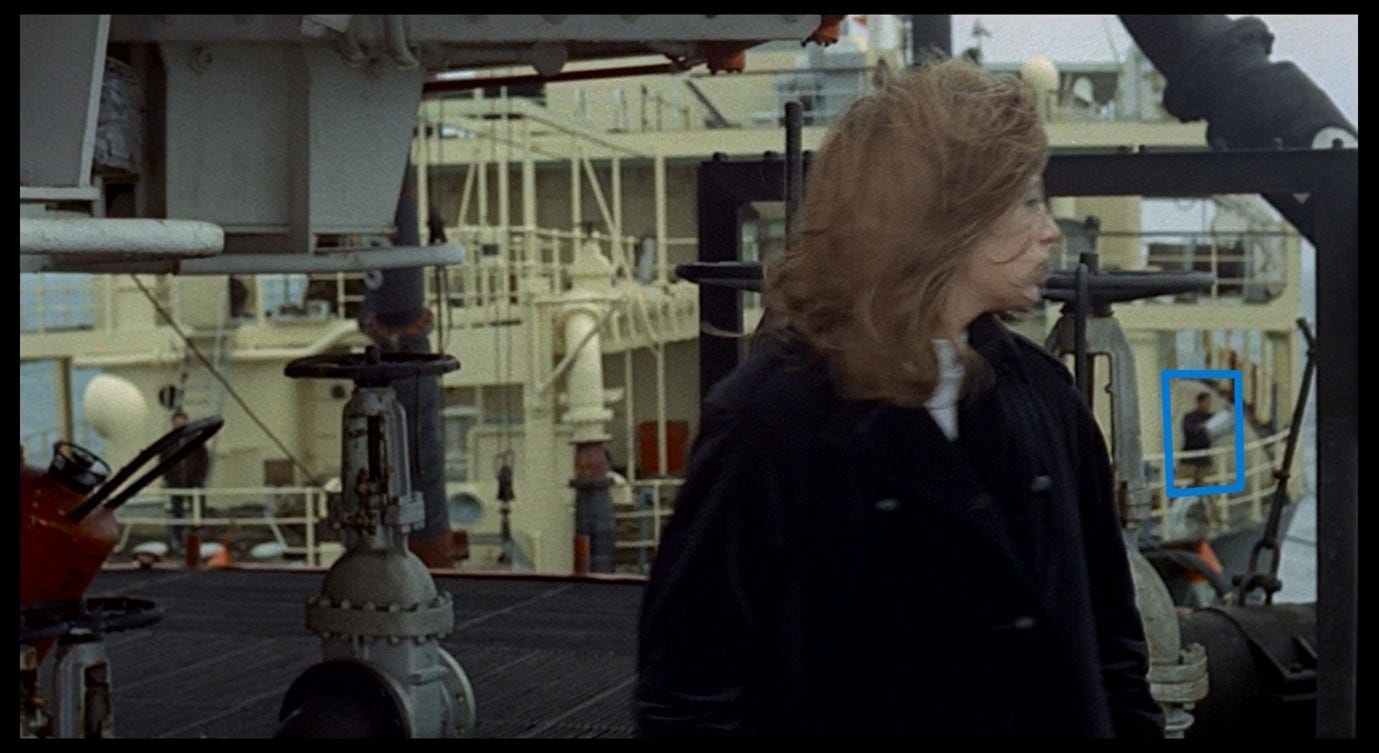

For the first minute, and intermittently throughout the rest of the sequence, we find ourselves simply observing the environment. The steel island and the tanker docked alongside it are established in the first three shots, beginning at a great distance, then coming closer, then closer still.

This echoes (in reverse) the establishing shots of the flare stack at the start of the film. In that case, the camera began in a position that no living being could safely occupy, then withdrew by stages to a more ‘human’ perspective, in order to survey the factory complex.

Here, too, the camera begins with a machine-perspective and progresses to a human one. At first, we are in the middle of the ocean, as far as possible from any signs of life. The image sways gently as though the camera were positioned on Valerio’s gyroscope toy, travelling safely across the rough seas that sometimes prevented Antonioni from filming on the SAROM rig.1 The cut to a closer angle, then to an even closer one, again gives the impression of an omnipotent camera that can be anywhere at any time.

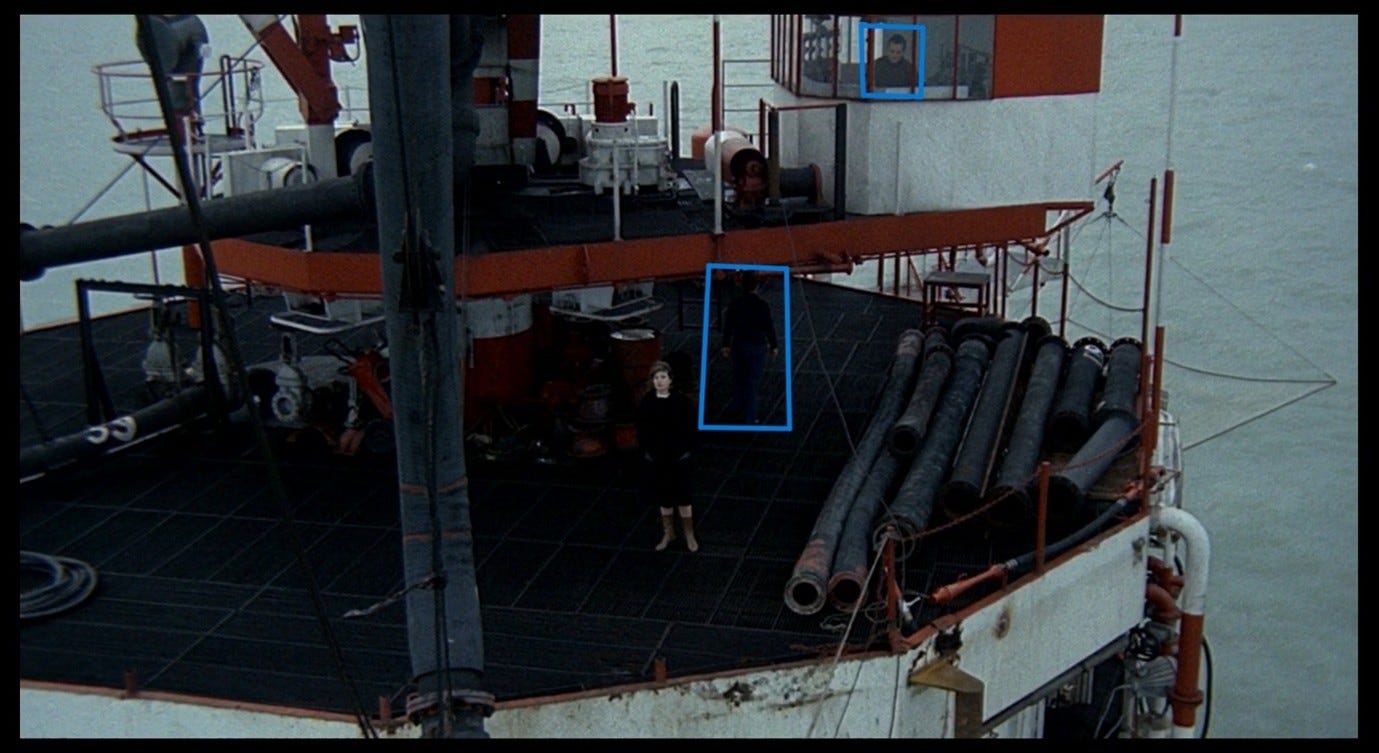

As this sequence proceeds, Antonioni takes advantage of the industrial structures to film from different perspectives. In the fourth shot, the camera looks down at Giuliana from a high angle (and she looks up at it), as it dangles from the pulley system that will soon transport Corrado back onto the rig.

Like the Medicina observatory, the rig has been designed so that every part of it is accessible, in one way or another, to the people working on it. The camera uses this design feature for a less utilitarian purpose, to find new ways of looking at the setting and new relations between it and the characters.

The transition from the previous scene, triggered by Ugo’s reference to rough seas, suggests a link between Giuliana anxiously looking down at the gyroscope-toy and Giuliana anxiously looking around her at the offshore rig, as though she had been miniaturised and transported into the toy.

Here too is an ingenious man-made structure that can remain stable even in the harshest conditions, a stark contrast with the unstable Giuliana.

In 1962, the newsreel La Settimana Incom featured a segment about the oil industry in the port of Ravenna.2 We see a huge buoy used to transport oil across the sea. The buoy somewhat resembles Valerio’s gyroscope, and like Ugo the newsreel marvels at the technology that facilitates Italy’s economic miracle.

The camera gazes into a vat of oil whose surface has the same texture as the pond near Ugo’s shack. As the scum on the surface contracts over a small, clean circle of oil (presumably left by an object that has just been dropped in), the narrator says, ‘This is the heart of contemporary civilisation.’

He rhapsodises over the achievement of those who built the SAROM island itself: ‘The engineers’ imagination has surpassed that of the artists and writers of science-fiction. These workers operate in an environment that would amaze Jules Verne.’ This, the newsreel suggests, is a place where childhood dreams of the future come true, but for the sake of quantifiable economic benefits rather than useless entertainment. ‘The new industrial landscape inspires artists as well,’ claims the voiceover, showing factory-themed paintings.

The functioning of the imagination and the aesthetic standards to which it adheres have been improved by technological and economic advances, and at the same time rendered subordinate to them.

Some of the images in this newsreel may well have inspired Antonioni to use SAROM as a filming location, and may even have inspired specific camera set-ups.

Like the paintings in the newsreel, Red Desert is a work of art shaped by industry. Karl Schoonover argues that

film’s visual strength stems from its adaptation of waste. From this perspective, [Red Desert] is itself a glorious by-product of the petrochemical industry, a form of aesthetic adaptation not unlike plastic.3

This is the kind of ‘adaptation’ modelled in the SAROM newsreel: the role of today’s artist is to work in harmony with these miraculous industrial processes to create ‘glorious by-products’ imbued with ‘visual strength.’ Such products are the exact inverse of our protagonist, Giuliana, who feels herself to be a distinctly inglorious by-product (‘casualty’ would be the more humanising term) defined by a lack of ‘visual strength,’ both in her role as a seer and as an object of the gaze. In Part 8, I discussed Schoonover’s comparison of Sette canne, un vestito (Antonioni’s rhapsodic industrial short from 1949) with Red Desert, and Leonardo Quaresima makes the same connection:

A most futuristic industrial plant is at the centre of Sette canne, un vestito. […] [E]verything refers to technologically advanced modes of production, which were at the vanguard of Italian industry at the dawn of the 1950s. The film’s emphasis on modern forms as well as its almost systematically complete exclusion of the artisanal, intensify its thematic orientation. The plant, isolated in the countryside, almost resembles the space station of a science-fiction film. (The voice-over commentary, in an attempt to lessen the spectators’ disorientation, makes reference, by contrast, to more familiar models by comparing the factory to a ‘mysterious castle’.) The buildings of the factory, framed from below, appear to us like skyscrapers of an American metropolis; the network of the pipes of the chemical plant recalls the configurations (and the imagery) of a new era. Here, as is evident, we are in perfect continuity with the sceneries and modernist-industrial ambivalences of Il deserto rosso.4

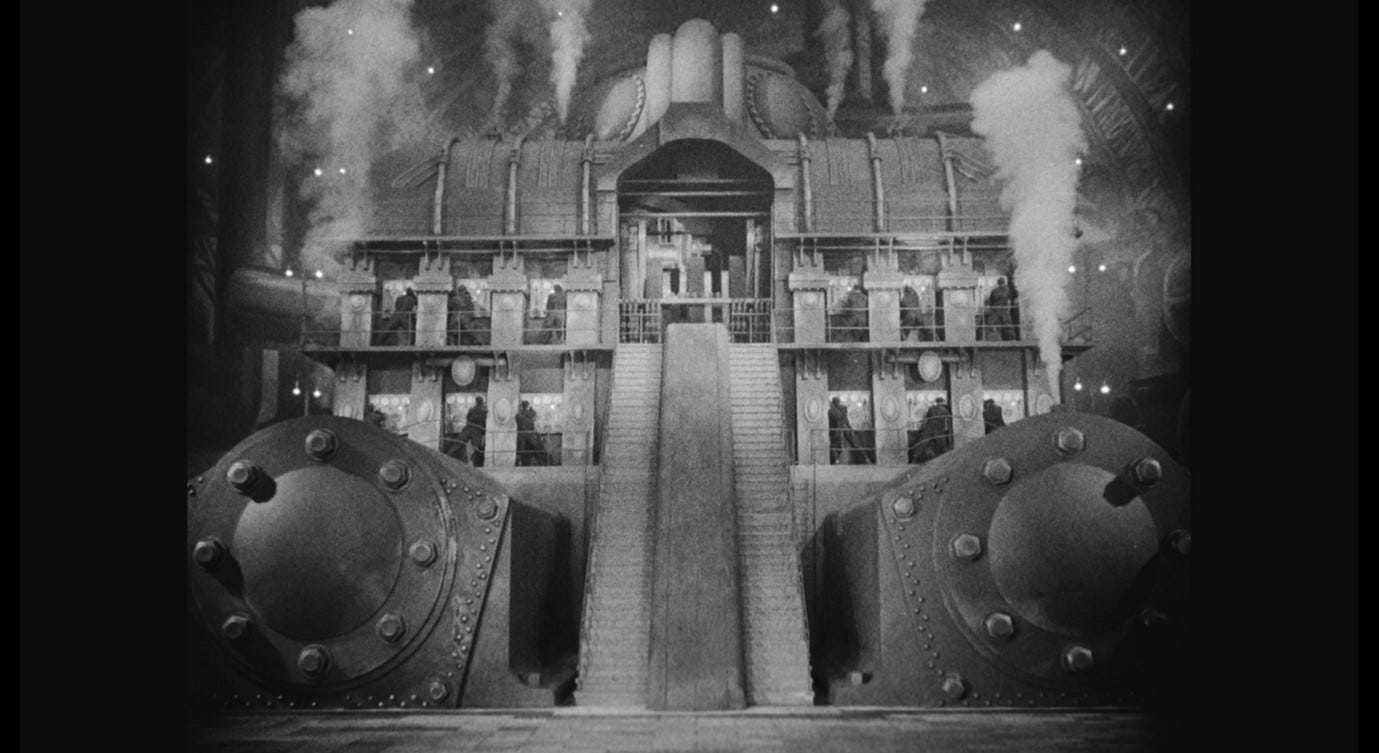

Quaresima highlights Sette canne’s ‘exclusion of the artisanal,’ its reduction of people to servants of machine-gods rather than skilled ‘makers’ in their own right. He distinguishes between science fiction and the ‘more familiar models’ of mythic fantasy, but his allusion to Metropolis is a reminder of how well these two models mesh together: Lang’s film gazes up at the towering M-machine and likens it to the ancient god Moloch.

The pipes in Sette canne’s rayon factory suggest to Quaresima ‘the configurations and imagery of a new era,’ that is, the intricate networks of wiring, girders, and roads that provide the infrastructure – at the micro and macro levels – of the modern world, but also the patterns found in modern paintings, sculptures, and films.

An artist might invent such patterns from their own imagination, reproduce them faithfully, or simply ‘discover’ them in their original industrial setting and allow that setting to direct the formation of the artwork.

We see examples of how this can work in several moments during the SAROM island sequence in Red Desert. Elena Past comments on the reflexive qualities of a specific shot, in which Giuliana navigates her way around a large black pipe, and the camera abandons her in favour of the pipe:

In shooting the black tubing, the camera moves smoothly along its curvatures: up, then left, up again, then left, and then down, down, precipitously, to where Corrado hangs in a chair lift over the water. This mobile camera traveling along the pathways of liquid fuel offers a moment of reflexive petrocinema, where the technology of the film industry investigates the petrochemical industry upon which it is based. […] Petrochemical modernity is built in the image of the liquid hydrocarbons that drive nearly every aspect of contemporary life. Both in form and subject, Red Desert traces the shape of this dynamic landscape.5

Indeed, from one point of view we can see an enquiring, curious spirit in Antonioni’s camera, eager to explore every inch of this structure from every possible angle. But rather than seeing the film as actively ‘investigating’ or ‘tracing’ the shapes and landscapes of petrochemical industry, we could instead see it as more passively being ‘dictated’ and ‘determined’ by its setting, not unlike the propagandist newsreel that obediently tells us what the petroleum industry wants us to hear. This scene becomes ‘petrocinema’ almost by necessity because it operates in a context where there is nothing else to become, no other form of art to be made. We feel driven along this pipe like petrol, like the effluent that ‘has to end up somewhere’ and cannot really choose where it ends up, or like Antonioni’s characters whose lives and actions are shaped by impulses they do not understand (see Parts 18 and 19).

When Giuliana glances at the black pipe, she seems characteristically uncertain where to look or what to make of her surroundings, but the camera moves with confidence. We might remember Giuliana’s attempt to trace the embroidered thread on the sofa in Mario’s apartment.

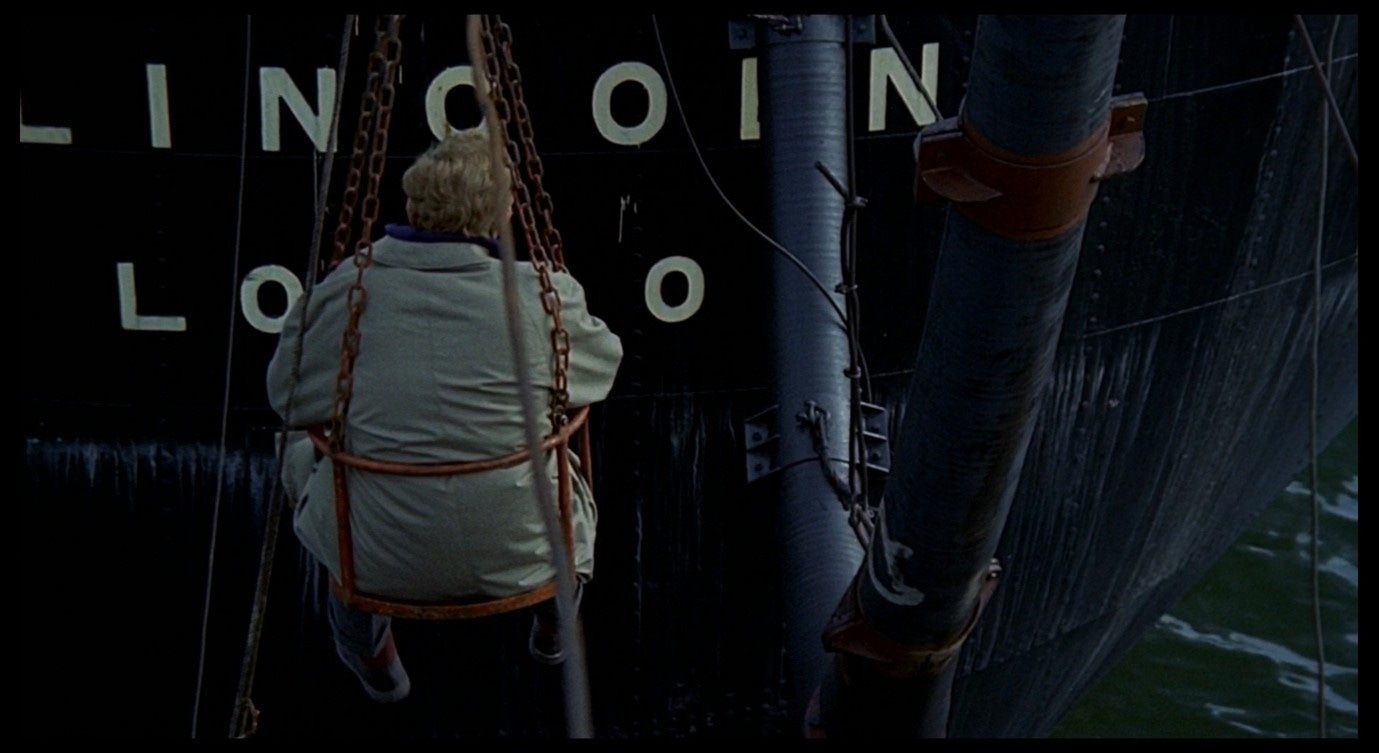

Whereas in that case she quickly lost the thread and began gesturing nervously with her hands, here the camera follows the oil-pipe until its destination (the ship docked beside the rig) becomes clear. The camera movement is completed at this moment of clarity; in the same moment, it finds Corrado being transferred back to the rig. As well as being perfectly timed, the shot establishes a pleasing symmetry between the journey of the black pipe (transferring oil from the rig to the ship) and the journey of the chair-lift (transferring Corrado in the other direction). While Giuliana explores her surroundings in a state of confusion, we do so with a robotic lucidity.

After the long-lens panning shot of the black pipe, the camera switches to a wide-angle shot in which we can clearly see almost the entire pipe and the context in which it operates. Giuliana hesitantly takes a few steps, unwittingly finding herself at the centre of a large metal frame.

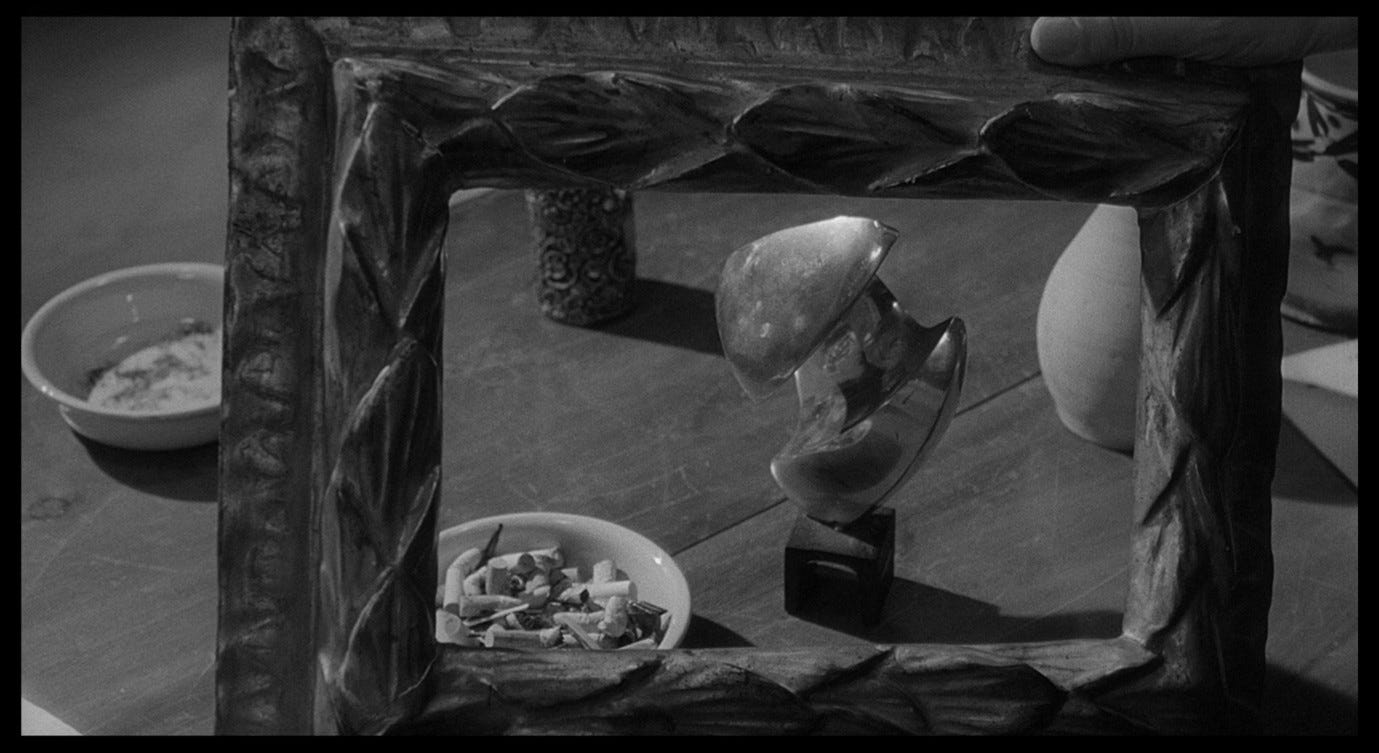

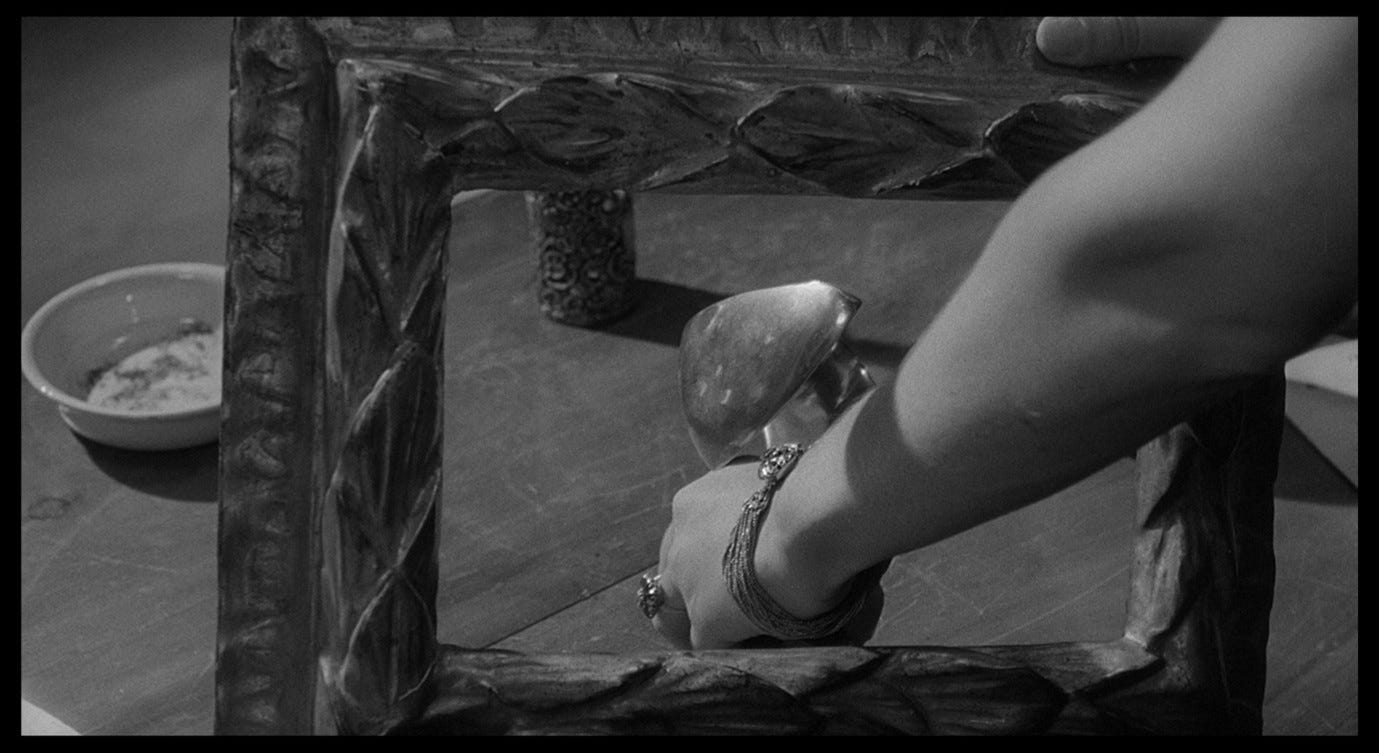

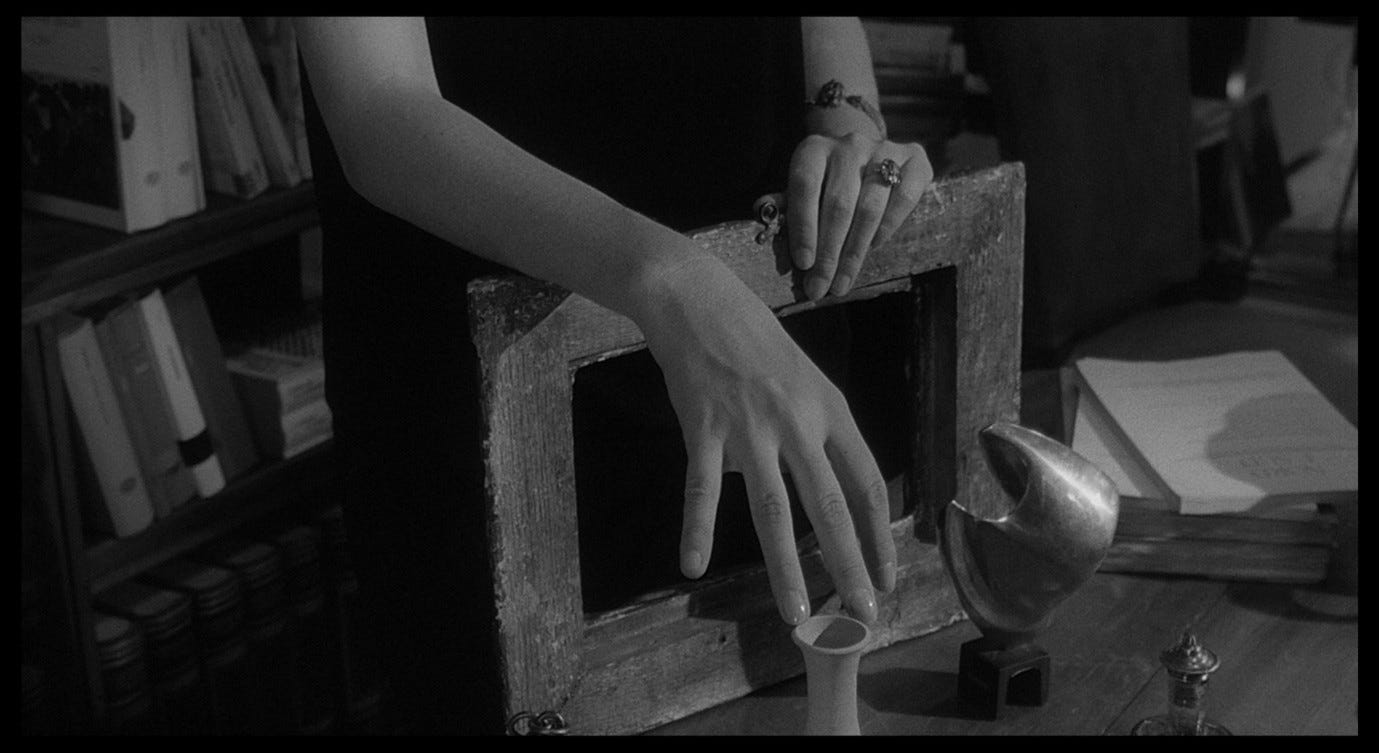

‘Every time I enter a strange office, public place, or private home, I get the urge to rearrange the scene,’ Antonioni once said, speculating that this probably stemmed from ‘the instinctive urge to feel myself in physical harmony with my surroundings.’6 By the same token, his films are attuned to the disharmony a person might feel when they are at odds with their environment, especially if they do not have the power to rearrange it. At the beginning of L’eclisse, Vittoria idly moves objects behind an empty picture-frame, seemingly to create a more pleasing or decorous composition. For a moment, the picture-frame prompts her to treat her immediate surroundings as though they were a work of art, but she gives up with a sigh of ennui, unable to create even the smallest oasis of harmony amidst the clutter of Riccardo’s living room.

In the moment we are looking at in Red Desert, the stationary camera observes the industrial machinery and quietly allows Giuliana to take her place within it. The frame-within-the-frame in this case has no aesthetic function, but seems designed to facilitate control of the black pipe, and now (for a few seconds) to facilitate control of Giuliana. Vittoria treats the world as an artwork that cannot be properly composed; the world treats Giuliana like equipment that cannot help but become part of an industrialised composition. The moment in L’eclisse feels lethargic and disillusioned, depressed by the revelation that reality is just a series of endlessly reorganised frames-within-frames; the moment in Red Desert feels passive and cold, quietly allowing the setting to determine the content of the frame, and of the frame within the frame.

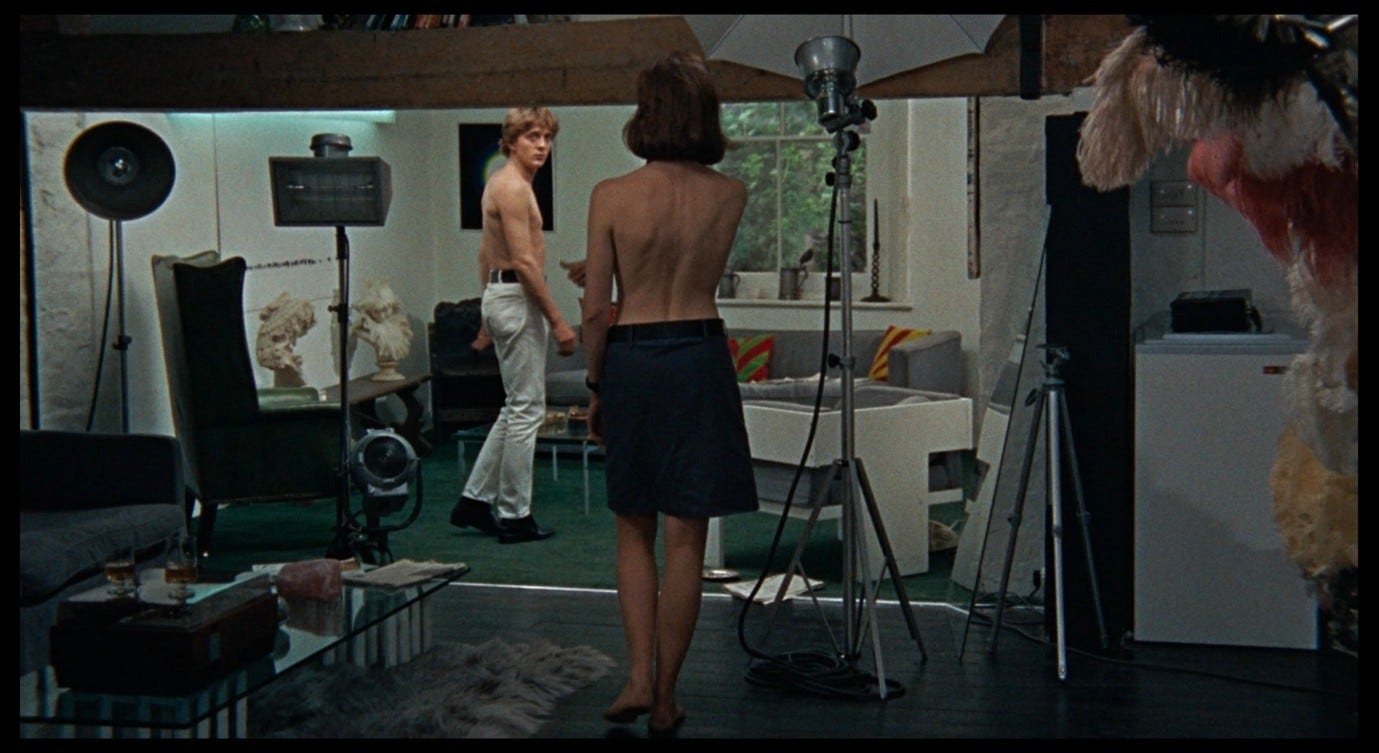

In another reflexive sequence in Antonioni’s next film, Blow-Up, the photographer is visited by the woman he photographed in the park. The propeller he bought in an earlier scene has just been delivered to his home, and he and the woman discuss where he will put it. She approves of his choice: ‘It’ll look good there, it’ll break up the straight lines.’ He needs to keep the photos of her for the same reason, because they will allow for the emotional contrast he needs at the end of his forthcoming collection.

The first minute of the SAROM sequence in Red Desert seems similarly concerned with how the space is ‘broken up,’ looking from different angles to explore how the pipes, girders, cables, and bits of equipment left lying around can be arranged to create different aesthetic effects, or to evoke different feelings. On this level, the sequence becomes more like the ‘investigation’ Past refers to, more challenging in its relation to the industrial structures. How does this space change depending on how we look at it? What happens when contrasting processes (pipe and chair-lift) and substances (oil and person) are visually equated with each other? If we look closely at the black tubing inch by inch, is it more legible, or easier to engage with, than when we look at it all at once from a distance?

What makes these questions disturbing is that the answers to them, if they exist, are beyond our reach. Just as the photographer in Blow-Up and Vittoria in L’eclisse are ultimately frustrated in their attempts to find meaning, coherence, or pleasing aesthetic effects in the world around them, so Giuliana seems lost among the objects of the steel island. This setting might make sense to a robot and is easily navigable for the film camera, but from a human perspective it is an intricate maze of patterns, endlessly broken up and then broken up again as we examine it from different positions. The camera’s investigation of the industrial space is like Niccolò’s ‘identification of a woman.’ It is exploratory but not informative; it shows us a great deal but does not fill in the context that would aid our understanding.

Only when Corrado is winched back onto the oil rig do we find out why we are here: he has visited the nearby ship to discuss his plans for the South American venture. For a man in Corrado’s line of work, even basic interactions require considerable time and effort. The SAROM island only exists because tankers are too heavy to safely enter the shallow waters in the port of Ravenna, meaning they need to collect oil and other supplies at offshore rigs. This also means that if someone from Ravenna needs to board one of these tankers, they need to take a boat to a rig. Then, to get from the rig to the ship and back again, they need to take the chair-lift. We infer all this, if only unconsciously, at the moment when Corrado’s professional interaction has been successfully completed. If we pause to think about it, or to see the situation through Giuliana’s eyes, we might find it extraordinary that such ingenious circumventions of nature have become part of everyday life, and that men like Corrado and Ugo take all this in their stride.

As he disembarks from the chair-lift, Corrado proudly tells Giuliana about the expenses he will save on materials and personnel. Unlike the attempt to recruit Mario, this business trip has gone well.

His boast reiterates the utilitarian mindset that defines this setting, where functionality and efficiency drive every decision. Both of his answers to Giuliana’s question (‘What will you take with you?’) underline this point: he thinks first of the ‘equipment needed for the project [l’attrezzatura dell’impresa],’ and names several specific items, but when pressed to say what personal things he will take, he says, ‘Nothing; two or three suitcases.’

Perhaps when we hear him say ‘nothing’ and realise he has no personal belongings to speak of, we also notice that there is hardly anything personal in the setting of this sequence. We hear Corrado exchange goodbyes with the colleague he was just speaking to on the ship, but we only glimpse that colleague for a second as the camera tilts past him. By the time Corrado is back in the frame, the other man is out of it.

Later, in the background, we will glimpse someone on the ship tossing a bucket of waste into the sea.

On the SAROM island, the worker we see walking past Giuliana and the worker operating the chair-lift from the small control room seem to blend into the rest of the attrezzatura of this setting.

We might connect the medium shot of the man in the control room with the wave of thanks Corrado gives as he arrives safely on the rig, or we might just as easily miss these details and assume that the chair-lift moves automatically.

The people here serve the same functions as levers and pipes, starting and stopping mechanisms and disposing of waste products. We may remember Giuliana’s brief, humanising exchanges with the workers at the observatory, and notice that there are no such humanising moments on the island of SAROM.

When Corrado talks about equipment, Giuliana gives him a blankly frustrated look and explains that she wants to know what he will be taking ‘of yours [di tuo],’ what personal things.

When he smilingly admits that the answer to that question is ‘nothing,’ Giuliana looks to one side with a quiet laugh, amused both by Corrado and herself, and by the difference between them.

He is so blithely efficient, so un-attached to the things around him; she represents the opposite extreme. She says that she would want to take ‘everything’ with her – everything she sees or touches (literally what she has ‘under hand [sottomano]’) every day – even the ashtrays.

In his typical, cheerfully patronising tone, Corrado explains how misguided this is: you would end up taking your entire home town with you everywhere you go, and you might as well stay where you are. As in earlier scenes, he peppers his speech with small rhetorical gestures, staring into the distance as he imagines the impossible things one would have to pack for such a trip, before cocking his head and smiling at Giuliana as he comes back to earth for the ‘so you see...’ conclusion.

We do not see Giuliana’s face when she reacts. By turning and walking away, leaving him smiling awkwardly, she seems to reject whatever point (or joke) he was trying to make.

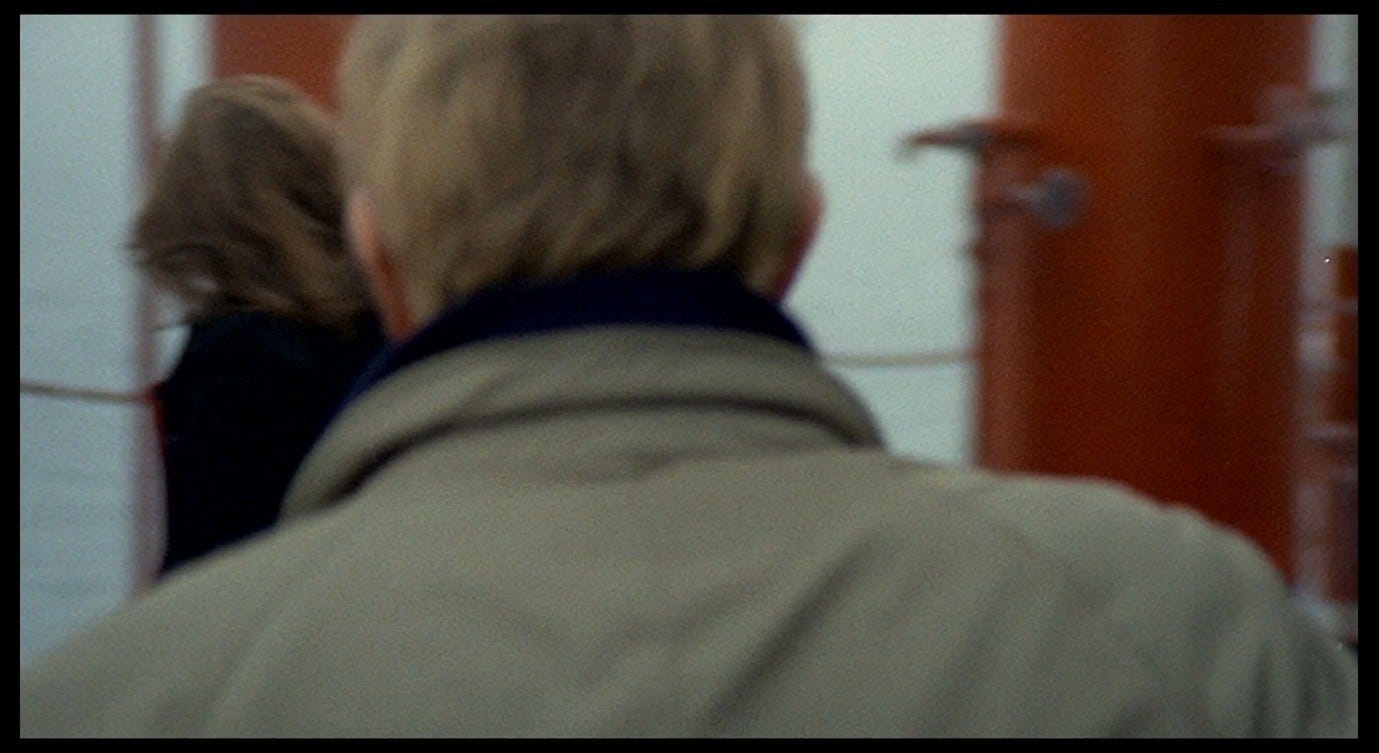

Up to this moment, Corrado and especially Giuliana have not been perfectly in focus. This may have been an accident due to the difficult filming conditions. The effect gives certain shots an almost documentary feel, reminding us that this was a hasty location shoot and that the workers we see in this sequence are real-life SAROM employees. However, the effect also dovetails with the frequent use of blurred images throughout the rest of the film. The two characters are, so to speak, not quite in focus for each other, not quite talking about the same thing. Corrado is absorbed in the practicalities of his work, while Giuliana could not be less interested in these – she is trying to change the subject.

When she turns away from him, the camera changes position, switches to a wider lens, and switches from a mode of static shot/reverse-shot to a dolly that moves backwards across the rig, with Giuliana walking towards the camera. Now she is perfectly in focus and the image is crisp and clear, more like a ‘movie’ than a documentary.

Giuliana is moving herself and Corrado into a new position, to reorient their dialogue and the way in which they relate to each other. Even the diegetic mechanical hum that has persisted on the soundtrack until this moment suddenly dies away, almost exactly when the camera begins to dolly backwards.

It is significant that Giuliana walks and faces away from Corrado while giving a speech on the topic of ‘leaving’ and ‘abandoning’:

Sometimes you read in the announcements, in the papers, ‘for sale because we are moving out.’ As if that were a reason to abandon everything one has, or even a part of it. Why? It shouldn’t be like that. How do you know what you’ll need? And then the things and the people you leave behind – will you find them again when you come back? And if you find them, will they be the same?

As the characters traverse the rig, the camera changes position again, twice: first to capture their movement with a long lens, retaining our sense of proximity to them and causing some spatial confusion; then to register the characters’ new location with a wide shot.

By the time Giuliana asks, ‘How do you know what you’ll need?’, she has come to rest in front of a girder, with a ladder beside her, and Corrado is standing by the railing in front of her, so that they are facing each other again. The migration from one side of the rig to the other helps to illustrate Giuliana’s point. She and Corrado leave one place and re-locate to another but she takes him with her, and when they are back together they arrange themselves in more or less the same position as before. They lose each other for a moment, then find each other. In the process, they, their context, and the nature of their conversation may have changed.

In her speech, Giuliana is half-seriously judgemental about people who sell their belongings – any belongings – when they move house. In literal terms, she is expressing a kind of hoarder mentality that refuses to throw anything away. In response to Corrado’s literal-minded comment about ‘taking your home with you,’ she doubles down and insists that there is something strange about leaving or abandoning anything or anyone that is a part of your life. Beyond her literal meaning, though, she is trying to tell Corrado something about herself and her state of crisis. Giuliana feels a desperate need for connection and attachment. The problem, as we see throughout the film, is not so much that she cannot let go of such attachments, as that she simply does not have any. Corrado’s account of his personal belongings – ‘nothing’ – could be Giuliana’s as well. In her state of extreme loneliness she longs to connect with everything, even inanimate objects. To be so casual about these failed connections seems unthinkable to her.

While they talk, Giuliana stands with her hands in her pockets (she is clearly very cold) and Corrado holds onto a nearby railing, then a nearby ladder, with one hand.

His attachment to the world is casual, easily formed and easily broken. Like a buoy with a gyroscope, he can lean in different directions without becoming de-stabilised. She appears more exposed and isolated, more in danger of falling or sinking. At the end of this sequence, we will see her poised on the edge of the rig, precipitously close to the ocean (as when she drove to the end of the pier), reaching out repeatedly to a boat that needs to come closer in order to pick her up, but never does.

The camera travels all over the rig but withholds context and explanations, keeping us in a state of un-moored confusion. Giuliana is similarly un-moored, and seems especially so in a setting like this one, appearing as lonely on the rig as the rig appears in the ocean.

Earlier, in Mario’s apartment, she described a feeling (attributed to the ‘other woman’ in the clinic) of losing the ground beneath her feet, and of feeling as though she might drown or suffocate. Now here she is on a so-called island, but with no actual ground beneath her feet: the screenplay notes that on the soundtrack we should hear ‘the sea that beats constantly against the iron pylons supporting the island.’7 As I mentioned above, this location was sometimes too perilous to film in, and the fears Giuliana expresses in this setting are fundamentally to do with the precarity of human relations, or of human existence itself. Her fear of leaving people and then finding them changed when you come back recalls Anna’s fear at the beginning of L’avventura, when she hesitates to reunite with Sandro: something has changed during their separation and she will now find him literally present but, on some deeper level, completely absent, like solid ground that is not really there.

In response to Giuliana’s concerns, Corrado posits that one might simply leave and never return. As we have already learnt, constant change – travelling to new places and changing his ‘historical context’ – is a way of life for him, and this does represent a kind of solution to the problem Giuliana faces. The world around her is constantly changing, her relations to things and people slipping away from her; Corrado instead is constantly slipping away into new worlds, preventing the formation of any new relations. He is also, of course, hitting on Giuliana. Her husband is away; Corrado will soon be leaving as well, perhaps never to return; their window of opportunity (for having sex) is closing.

Typically, Giuliana backs away from these hints – literally moving backwards, holding onto the ladder for stability before settling against the pillar behind her and putting her hands back in her pockets – with a slight, dismissive laugh. At the same time, and just as typically, she surprises Corrado by striking a tone of emotional intimacy:

If I had to leave, never to return, I would take you with me too. Yes, because now you’re part of me; that is, of what I have around me [quello che ho attorno].

The point here is not so much that she has added Corrado to the inventory of animate and inanimate belongings she intends to carry with her wherever she goes. It is her failure to connect with the things she has attorno that is plaguing her. Later, she will express a wish to have all the people who have loved her ‘around me [intorno a me], like a wall,’ but her problem is that they are not there: there is no wall. There are just people she wishes to relate to in that way, but cannot.

As I said above, the workers on the SAROM island and the nearby ship are part of the attrezzatura of the impresa constituted by this structure-vessel relationship. Like the other industrial labourers in Red Desert, they are marginal figures, but pointedly marginal. When we first met Giuliana, she was failing to engage with the striking workers, and that encounter sensitised us to notice these people who lurk around the edges of the film without ever quite being centralised. Mario is a good example: we become aware of him as Giuliana’s former fellow patient in the clinic, as the potential victim of Corrado’s exploitative recruitment drive, and as the interlocutor who prompts that famous image of Giuliana against the out-of-focus red girders. But we never get a good look at him, so he remains more or less as anonymous as the other workers in Medicina. The marginality of the SAROM workers is particularly interesting because, as at the observatory, there is a notable contrast between the hugeness of the structure and the smallness of those who keep it functioning, but in this case the workers are more insistently de-emphasised, more thoroughly excluded from the film image.

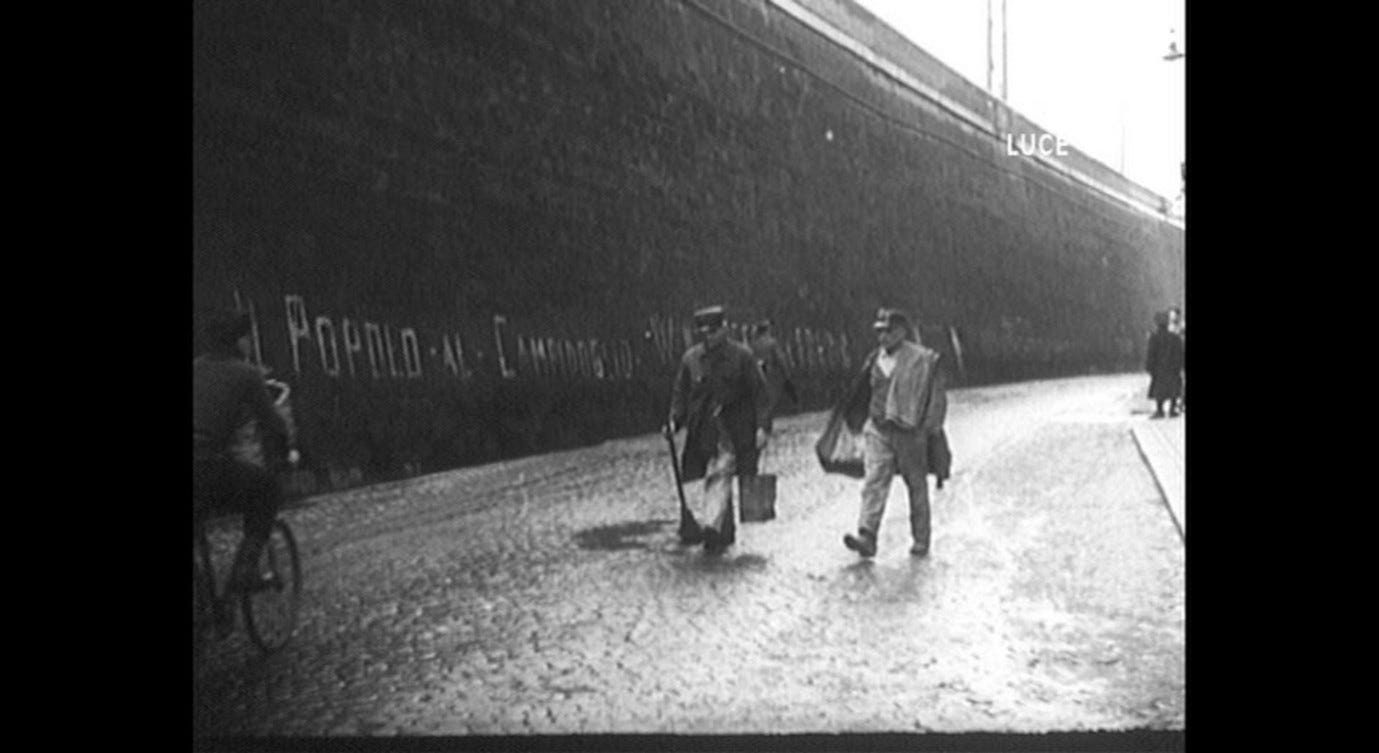

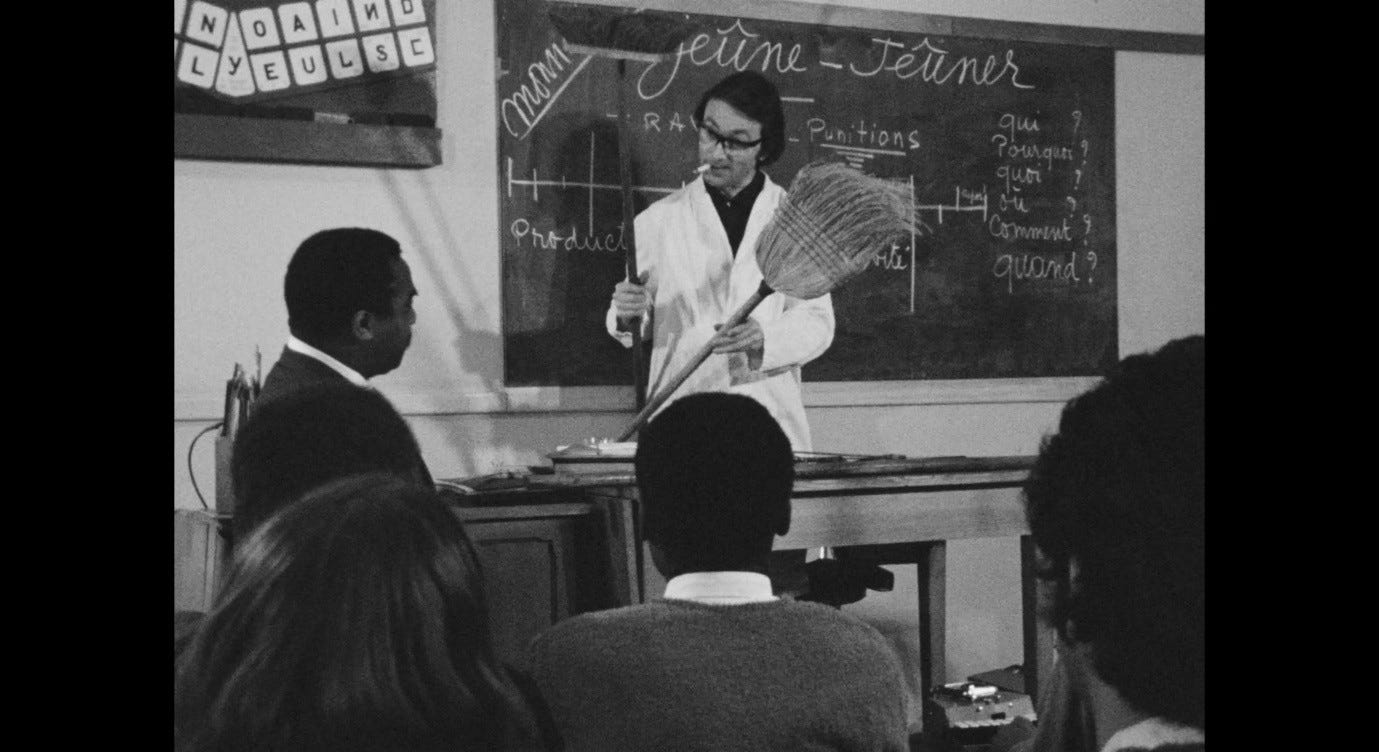

In 1948, Antonioni made the short film N.U. (which stands for Nettezza urbana, the city sanitation department), portraying the lives of street-cleaners in Rome. The brief narration at the start emphasises the marginality of these people:

In the course of a day, we encounter many people, many things and labours [lavori] that seem habitual and familiar, but about which we instead know very little. All the rest [beyond the little we know] is a mystery to us. Who are they, and how do they live, these street-cleaners [spazzini, which also means ‘scavengers’], these humble and quiet workers to whom no one deigns to give a look [sguardo] or a word? It does not seem to concern us [Sembra non ci riguardi]. The street-cleaners are part of the city, like something inanimate, and yet no one shares in the life of the city more than they do. With what eyes do they see it [Con quali occhi la vedranno]? Their work has begun a while ago by the time the city wakes up.

The line about the street-cleaners being part of city like inanimate objects (i.e. lifeless), but conversely being more involved in the life of the city than anyone else, recalls the ambiguity around life-like statues and corpse-like living people in Journey to Italy. N.U. reorients our focus towards a dimension of Rome that is vital to the city’s functioning, and to its beauty, but that is taken for granted and normally goes unseen. It asks us to see the city through others’ eyes, to look with a new sguardo and an altered sense of what concerns us (ci riguardi).

The film begins by tilting down from a speeding elevated train to a cluster of shacks beneath it, where street-cleaners are being assigned their daily tasks.

This visual link-and-contrast, reminiscent of Metropolis, between above and below, the speeding train and the trudging labourers, is then repeated with variations. The ancient Flaminio Obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo is juxtaposed with the sweeper on the ground, rinsing his broom in the water spouted by a reclining stone lion.

The dome of St. Peter’s looms over another gang of sweepers from behind an iron railing: first we see the spazzini from a low angle, and one of them briefly obscures the dome as he passes the camera; then we see them from a high angle, their eyes on the ground as they clear leaves from the cobbles.

A man pushes a wheelbarrow past the Fontana dei Dioscuri, pausing to toss his used cigarette into the barrow but not to glance at the fountain.

Towards the end of the film, we see several street-sweepers with their brooms dragging along behind them – even in moments of leisure, they are still cleaning the streets.

The last of these broom-draggers is juxtaposed, as in the first shot, with a speeding train. The train roars past the camera, leaving in its wake a classic Antonioni desert, a wide avenue glistening with rain (there are dark grey clouds overhead). A lone street-cleaner enters from the right and begins his slow walk towards the horizon, his broom positioned so close to his legs that it seems to merge with them.

The train – a symbol of speed, progress, and modernity – seems to have left this man (and the camera) behind, to have discarded him. But for the purposes of this film he is the concluding, defining image, indeed the only sign of life that remains in this final shot.

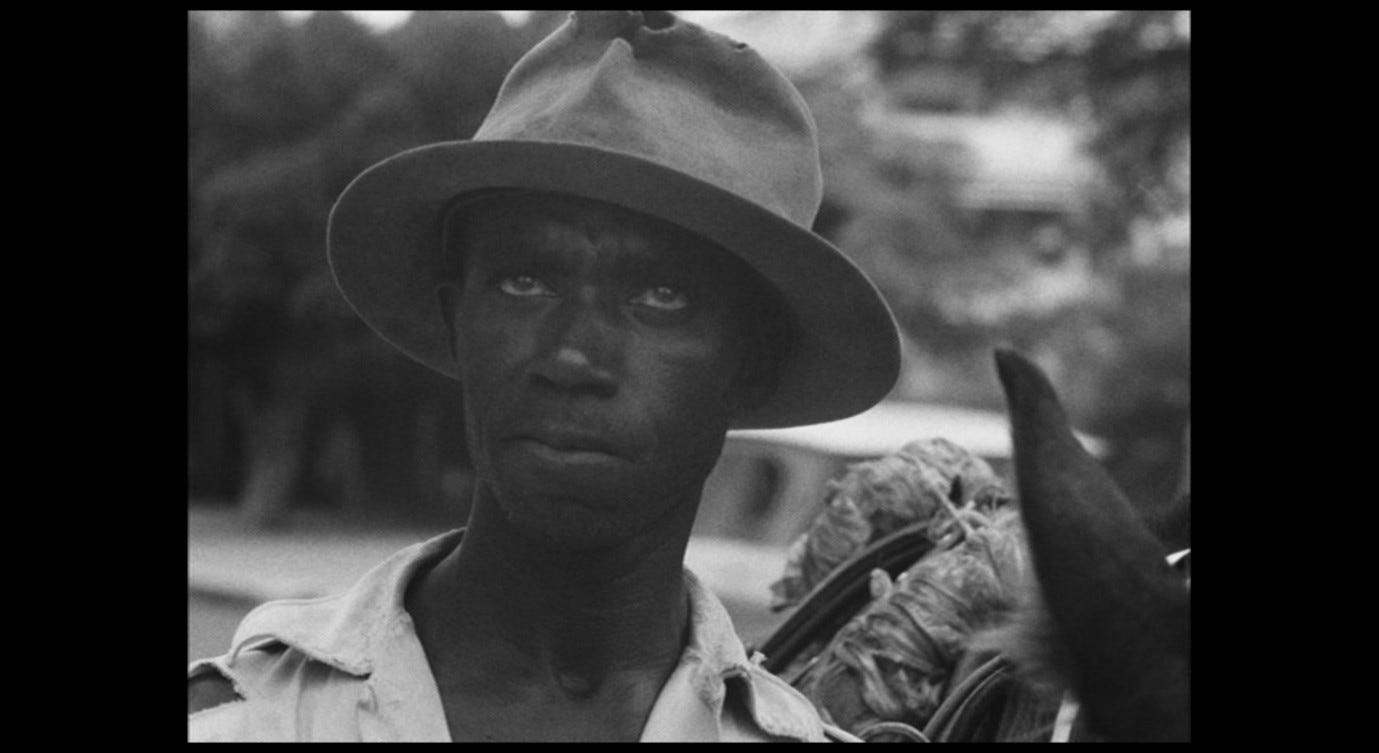

In Mandabi, Ousmane Sembène uses the same kinds of imagery and juxtapositions as N.U. to portray Abdou’s life in Paris. This brief montage accompanies the reading of Abdou’s letter to his uncle in Dakar, in which he explains how his 25,000-franc money order should be divided up and kept safe. Abdou has earned this money through street-cleaning: indeed, he is in a similar position to the protagonist of Soleil Ô, whose French language lessons become comically fixated on the word balai (broom) because the teacher has decided this is the only word these immigrants will need to know.

Abdou, unlike Hondo’s characters, is not angry. From his point of view, he is working hard, being duly rewarded, and providing for his family back at home. But the rest of Mandabi will show how all of Abdou’s money is frittered away or stolen once it arrives in a Senegal that is now independent from France, but still profoundly colonised.

Mandabi’s Paris montage begins by looking up at the Eiffel Tower, then tilts down to find Abdou sweeping the street – we see his broom before we see him.

The shape of his broom provides an ironic visual rhyme with that of the tower: as in N.U., we are asked to see these over-exposed monuments that define this famous city (the tilt-down is repeated with the Arc de Triomphe) as being maintained by un-regarded labourers down below.

At the end of the montage, Abdou looks out of a train window at the Eiffel Tower, whose pinnacle he cannot see from this vantage point. Then we see the train running along an elevated track, disappearing into the urban jungle.

As at the end of N.U., we sense that the person we have been watching is being ‘left behind’ or discarded, but this time we lose sight of the street-cleaner altogether amidst a space that is the opposite of a desert. The heavily built-up structures of Paris are like the forest of bureaucratic and deceptive traps that eat up the money order. Abdou, for all his integrity and dignity, is powerless to overcome these malevolent forces.

Sembène includes an even more Antonioni-esque moment in his earlier film, Borom Sarret, whose protagonist is a cart-driver living on the outskirts of Dakar. He makes a prohibited trip into the heavily European-ised city centre and is punished by having his cart confiscated. As he slowly walks his horse back home, he looks up at the huge apartment blocks in which he cannot afford to live, and at the traffic lights that force him to pause and reflect on his situation.

We hear his inner thoughts:

Red light. We always have to stop. Leaving. Going to sleep. When? This is jail. This is modern life. This is the life in this country. Go. I’m moving forward. These homes. This is it, these homes. Yesterday it was the same. We work for nothing.

His insistent repetition of ‘ça c’est la vie moderne, c’est ça, ces maisons, c’est ça’ capture his feeling of revelation, the sense of ‘this is it’ as something terrible crystallises in the reality around him. The buildings he looks at are like the ones at the end of L’eclisse, a repetitive series of sharp angles framed bleakly against the sky, taking over Dakar as they have taken over Rome.

The wagoner recognises that something has happened to his country, as well as to him personally, with the onset of ‘modern life.’ As he walks home, he passes the Place de l’Obélisque, in which a monument celebrates Senegal’s independence, with the year 1960 inscribed in Roman numerals. Sembène pans and tilts from the wagoner to the monument, then lingers on this image with the same bitter irony he would direct at the Eiffel Tower in Mandabi.

Giuliana, in Red Desert, is equivalent to the residents of the buildings Sembène’s wagoner looks up at, or to the middle-class Parisians who pass Abdou on the street, or to the distraught wife in N.U. whose husband tears up a letter and tosses the pieces on the ground. The street-cleaner who calmly picks up those fragments, and just as calmly allows some of them to drift away on the wind, might well be having the same thoughts as the wagoner in Borom Sarret.

With what eyes do they see this city?’ asks the N.U. narrator; Sembène answers this in words as well as images. Red Desert tends to focus on how these feelings – of being left behind, being imprisoned, being in thrall to the systems and structures around us – are experienced by Giuliana. But the pointedly marginal presence of industrial labourers, at key moments in the unravelling of Giuliana’s psychic drama, represents an important clue to the nature of her problem. It is as though she hears the thoughts of Sembène’s wagoner from inside her alienating modern flat. This does not prompt an awakening of social conscience, but an awakening of personal existential dread. The monumental presence of a structure like the SAROM island, the smallness and invisibility of the men who operate its mechanisms, and her recognition of her own place within these structures, makes her realise: ‘This is it, this is prison, this is modern life.’ I will come back to this topic in Parts 27-29, when we will meet the most oppressed and disgruntled (though still pointedly marginalised) workers in Red Desert.

Next: Part 26, The story of the incident.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Niccolini, Flavio, ‘Diary’ (1964), trans. Maggie Fritz-Morkin, Words Without Borders (02 March, 2011). The original Italian text is published in Michelangelo Antonioni, Il deserto rosso, ed. Carlo di Carlo (Bologna: Capelli, 1964).

‘La Settimana Incom: Numero unico dedicato a Ravenna e all’attività del porto. La raffineria di Sarom.’ Available on YouTube via the Istituto Luce online archive. All translations mine.

Schoonover, Karl, ‘Antonioni’s Waste Management’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 235-53; p. 248

Quaresima, Leonardo, ‘“Making Love on the Shores of the River Po”: Antonioni’s Documentaries’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 115-133; p. 117

Past, Elena, Italian Ecocinema: Beyond the Human (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), pp. 35-36

‘Let’s talk about Zabriskie Point’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 94-106; pp. 105-106

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 480