Everything That Happens in Red Desert (26)

The story of the incident

This post focuses primarily on the topic of suicide.

Giuliana’s confession – for want of a better word – about the truth of her incidente is a pivotal moment in Red Desert. People who write about this film often describe Giuliana as suffering from depression caused by a car crash, which is indeed how her predicament is described by Ugo during the factory tour sequence. The twist, as we find out now if we haven’t guessed it before, is that her depression preceded the car crash, and that the crash was deliberate. No one dies in Red Desert – except perhaps the man who screams out from the infected ship – but it is a film about suicide and death, and what these things represent. That last part is the most important: we are asked to see Giuliana as someone who is telling a storia, initially a false one about an accident, and now one that is closer to the truth about suicide, but still a partial and imperfect self-representation. The crash was not an accident, but it was still an incident, an occurrence whose precise nature is hard to define, raising more questions than it answers. The questions have to do with the difficulty of existing in the world (as a person), or in the frame (as a performer), or in the act of making a work of art. For Antonioni, the acts of looking, making films, and being alive are inextricably linked. The act of telling stories belongs in this list as well, and is just as challenging, just as prone to lead the actor into a state of oblivion.

We are a few minutes into the SAROM oil rig sequence: Giuliana has just told Corrado that if she left her home, never to return, she would take him with her because he has become part of her life, part of what she has around her (attorno). Corrado, seeming to reciprocate Giuliana’s intimate tone, comes closer to her.

We then cut to an incongruous shot of the other side of the rig, where the characters were before, but which is now devoid of life.

We see a ship in the far distance, out to sea and half-visible in the fog. The black tubing, presumably still feeding oil to the nearby tanker, dominates the shot in the middle ground. To the right, we can see the black metal frame that Giuliana momentarily stood behind. When we cut back to Corrado and Giuliana, she has turned and moved away from him to stare at the ocean.

As Corrado approaches her again, she turns and looks at him, one hand holding her collar against her cheek, then looks away and says, ‘If Ugo had looked at me as you have in the last few days [in questi giorni], he would have understood many things.’

The sequence of shots conveys a disorienting combination of intimacy and distance, connection and separation. The characters come together but are separated during the desolate cut-away to the other side of the rig; their eyes meet but then they both look away.

Moreover, despite Giuliana’s comment here, this sequence has not provided much evidence of Corrado’s understanding gaze. If anything, he has seemed out of step with Giuliana, uncomprehending in the face of what she is trying to tell him. Perhaps that changes in this moment, when she tells him that he is part of her. There are some significant details in the screenplay’s description of what happens here:

Corrado approaches her, looking at her tenderly. Giuliana has a moment of intimate discovery towards him [un momento di scoperta intimità nei suoi confronti].1

My awkward translation underlines the emphasis, in this stage direction, on the separation between Corrado’s emotion and Giuliana’s. The moment of intimate discovery, or discovered intimacy, is one that she has, it is her response to him. She feels seen, discovered, and intimately understood, but she may or may not be correctly interpreting his expression of tenderness. Corrado has, on one level, been hitting on her, and that may be the only intent behind his mawkish expression and attempt at physical intimacy.

By explicitly contrasting Corrado with Ugo, Giuliana is beginning to speak more plainly and clearly than she has done so far in this sequence. She has moved from insisting on her own connectedness to things and people, to admitting that she feels alienated. In the context of Corrado’s quasi-amorous advances, the reference to her husband also alludes to the conventions of the adultery drama, a genre with which Red Desert has a complex relationship (see Parts 9 and 16). The lonely woman whose husband does not understand her, and who finds a rare sense of connection with the drifter who passes through town, reminds us again of Ossessione, but again the echo throws into relief a distinction between the two narratives. In Visconti’s film, the focus was on simple, primal desires: Gino’s hunger for food is connected with Giovanna’s sexual hunger and both characters are drawn to each other as though the relationship were a matter of survival.

Red Desert takes place in a different kind of world. Both food and sex are readily available to Giuliana but she misses something less tangible that transcends both these needs. However, as she reveals now, her sense of lack is no less a matter of survival.

To some extent, Giuliana’s trust in Corrado is not misplaced. He recognises that she is not (or at least not primarily) expressing a sexual attraction to him, but that she is again trying to talk to him about her illness. When she says that Corrado has understood her in a way that Ugo has not, he immediately guesses what she means: ‘The story of the incident? And of the friend in the clinic?’ It does not require any unusual level of insight to figure out, as Corrado does, that this ‘friend’ was Giuliana herself – indeed, he clearly knew that when he heard this story in Mario’s apartment – but it does require something that Ugo is not capable of. When Giuliana says, ‘if Ugo had looked [guardata] at me as you have,’ she may simply mean that Corrado has paid some attention to her, that he has looked at her with something other than Ugo’s unseeing, robotic eyes, and that he assumes some form of connection (or at least the possibility of a connection) between him and her. Her use of the verb guardare sustains the motif of ‘looking’ set up in earlier scenes, reminding us of the contrast between her pathologically engaged sguardo (staring so hard at the ocean that she becomes absorbed by it) and the pathologically un-engaged sguardo of her husband. In the few days she has known him, Corrado has engaged with Giuliana, however problematically. He has listened, he has looked, and there has been some meaningful dialogue between them. From what we have seen, she has none of this with Ugo, or with Valerio, or with anyone else.

‘I didn’t want to tell you,’ says Giuliana. Each statement comes out haltingly: ‘I was ashamed. Not even Ugo knows. I had an agreement with the doctors. I had tried to kill myself.’ The sense of shame attached to her attempted suicide is emphasised by the gradual, tentative way she builds to this revelation. Corrado is similarly tentative in his enquiries, moving his hand up the rungs of a ladder as he moves from one question to the next.

This is a moment Giuliana has been working up to, stage by stage, throughout her friendship with Corrado, since that first pregnant look that passed between them in Ugo’s factory. When Corrado met Giuliana on the Via Alighieri, she asked what was ‘beginning’ between them, then asked what he had been told about her. In Mario’s apartment, she asked again how much he knew about the accident, and began revealing things through the displaced story of the ‘other woman.’ Now she is ready to take ownership of that story, and to take responsibility for the so-called accident that sent her to the clinic. Her journey, in this film, is one of gradual revelation, peeling back one layer after another until she reveals something like her self, something like the truth.

Before talking about her suicide attempt, Giuliana has re-positioned herself again in order to face Corrado from a slight distance.

More than a third of the frame on the left-hand side is occupied with an out-of-focus metal structure. Rusty, grey-and-white objects surround Giuliana, with a small amount of grey sky visible in the background. The image is bleak and claustrophobic, but not suggestive of entrapment. Appropriately, given what she is saying, Giuliana looks like she is hiding, and at the moment of revelation – when she says she tried to kill herself – she suddenly disappears out of the frame.

A parallel is drawn here between the act of concealing the truth and the act of ending one’s life; between hiding and making oneself disappear. To some extent, this has to do with the stigma attached to suicide, but if there is a moral or religious dimension to the shame Giuliana expresses, it remains implicit. By this point in the film, and especially following the incident on the pier and the tense aftermath with Ugo, we understand that Giuliana’s agreement with the doctors (to hush up the suicide attempt) was motivated by something other than Catholic guilt.

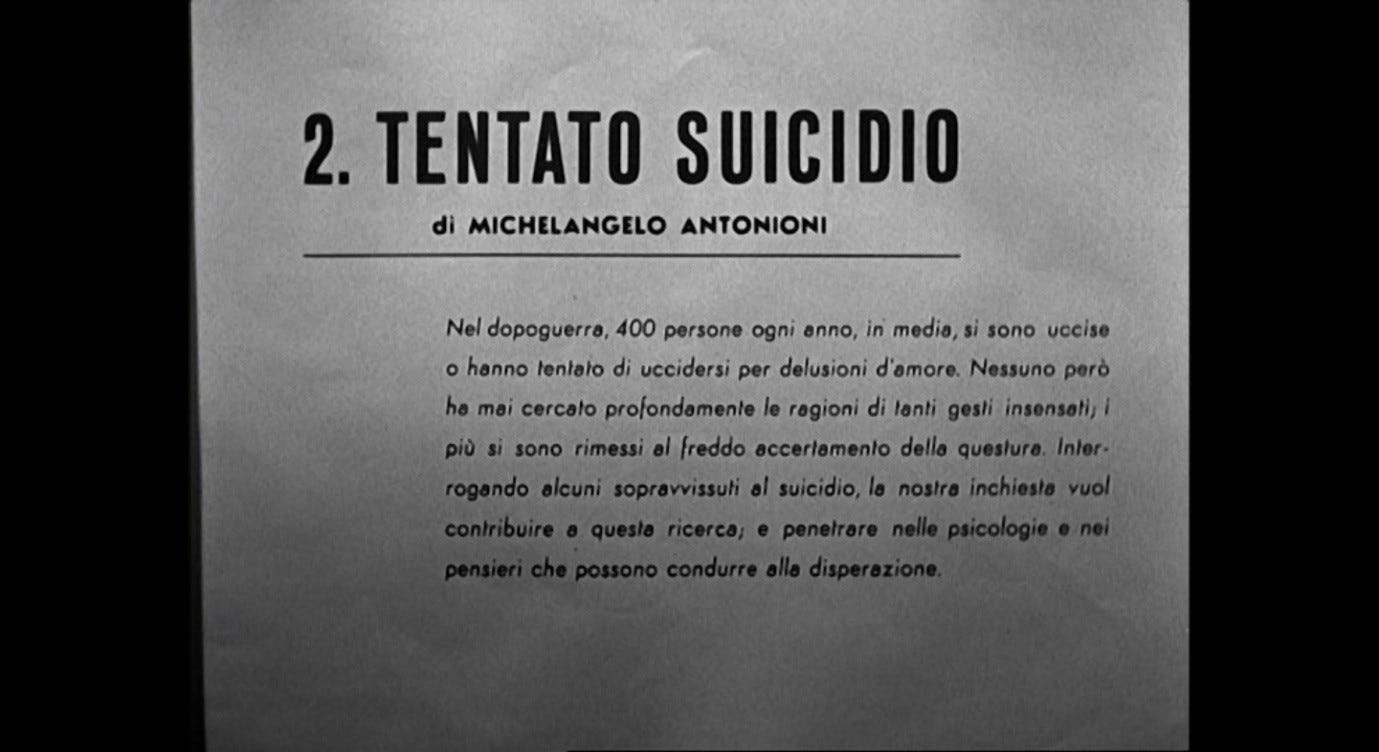

Ten years earlier, Antonioni contributed the segment ‘Attempted Suicide’ to the anthology film Love in the City. This 20-minute short is a fascinating mix of documentary and dramatic re-enactment, in which five women discuss their recent suicide attempts, all of which were motivated by amorous disappointments. The rather cold-blooded narrator observes that these women have ‘an almost morbid need [un bisogno quasi morboso] to make their stories known,’ both for their own and others’ sakes. One of the women explains that she wanted to participate in the film to try and make sense of what had happened, ‘by talking about it sincerely [con sincerità],’ and a similar intent seems to have motivated the film-makers: they are trying, through a serious and sincere discussion, to comprehend the nature of this phenomenon. But the film also casts doubt on the sincerity of these women, and in the process (perhaps unwittingly) calls into question its own posture of good-faith exploration.

‘Attempted Suicide’ opens with its subjects filing into a studio, where a fake building-front lies discarded to one side and a large white sheet has been erected as a backdrop for the scene we are watching.

Like the half-constructed (or de-constructed) film sets in La signora senza camelie, these explicit references to the artifice of cinema remind us that we are not seeing un-mediated reality.

Ned Rifkin argues that the film-making apparatus in ‘Attempted Suicide’ gives an insight into the divided selves of the interviewees:

The strong floodlights on these people […] cast dark shadows on the stark white wall behind them in the studio. In this context the extreme tonal contrast of the shadows of each person on the flat wall surface corresponding to, but not duplicating, their figures takes on another level of meaning. The discrepancy between themselves as totally secure human beings and the distorted forms which they project visually summarizes the acute problems of self-image from which these people suffer.2

I would question the distinction between the ‘totally secure human beings’ (in the flesh) and the ‘distorted forms which they project’ (in shadow). The film is interested in this dichotomy, and in the idea that these people might be distorting the truth in telling their stories, but there is a complex relationship between problems of self-image (how the interviewees see themselves) and other-image (how the film sees them).

The people are shadows, or rather silhouettes, when we first see them and when they file out at the end.

In between, the shadows they cast against the white sheet evoke the stories they tell: the shadow is the experience of attempting suicide, which is behind them now but still attached to them, still following them around.

And the people themselves seem anything but secure, especially in these opening moments. There is something performative about the way they file into the studio and stand around looking awkwardly at each other.

They are performing insecurity because they have been directed to do so, but this performance in itself seems insecure and hesitant…which makes their insecurity seem all the more real. These women will give candid insights (con sincerità) into events that really took place, but their movements and utterances also seem well rehearsed, carefully blocked and photographed. One of the women talks of wanting to be an actor. Another says that she committed a ‘fake suicide [finto suicidio]’ before trying again in earnest. In La signora, too, Gianni’s attempted suicide is labelled a ‘gesture’ rather than a real attempt, and for the same reason – he has not swallowed enough pills.

Both films are reflexively interested in the relationship between reality and fiction, in the cinema’s (or the actor’s) capacity to explore something ‘real’ while also in some sense ‘faking it.’

‘Attempted Suicide’ focuses on the failed love-relationship as a motive for ending one’s life. Near the beginning, the narrator declares that ‘love helps us to endure everything, but if love ends, everything collapses.’ However, the tone is a long way from tragic romance. The on-screen text accompanying the title card announces an intent to ‘investigate the psychology and thought processes that can lead to despair.’ This clinical, academic tone is sustained by the narrator, who concludes by deferring to the judgement of psychologists.

Although this short film is ostensibly about the kind of despair linked to amore, like Story of a Love Affair it also questions and subverts our assumptions about love, in this case by implying that the suicidal impulse must stem from deeper psychological causes than a romantic break-up. ‘I am sure they were lying,’ said Antonioni in an interview, ‘that they were exaggerating for who knows what reason of vanity or masochism.’3 His dismissive contempt perhaps explains why there is something cold and unsatisfying about ‘Attempted Suicide’, in which the interview subjects seem uncomfortable telling their stories. They seem, in fact, to be reciting dialogue that was agreed upon and rehearsed beforehand; the film-maker’s suspicion that they are dishonest becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But Antonioni’s comment also indicates that he is interested in something beyond the suicidal impulse as such. The ‘when love goes wrong’ platitude that opens the film has a wider application to emotional attachments, and as such is more resonant and suggestive than it seems. To return again to La signora senza camelie, Clara’s problem in that film goes far deeper than her loveless marriage to Gianni or her desperate affair with Nardo. Like Giuliana in Red Desert, Clara seems un-moored not only in the context of her love life and her career, but in terms of her very identity. Like the women in ‘Attempted Suicide’, she is caught in a liminal space between reality and artifice, and although she does not literally contemplate suicide, she seems on the verge of being annihilated by her predicament.

When Giuliana confesses to attempting suicide, this retroactively casts her previous dialogues with Corrado as investigations into the suicidal mindset, like the interviews in ‘Attempted Suicide’. At one point in the earlier film, the interviewer talks to a woman who made multiple suicide attempts, who was confined in a mental hospital for 23 days, and who still expresses suicidal desires now. The interviewer asks whether the thought of her children would stop her from ending her life. ‘The children are very important, of course,’ she says, ‘but sometimes you lose your head.’ Like Giuliana, she walks out of view of the camera, punctuating her comment about ‘losing her head’ by losing her place in the frame. She leaves behind the open window that reminds us of the one she had tried to jump out of – the window that represents the prospect of escape from her suffocating domestic life.

Another woman is asked whether she thought of her fiancé when she attempted suicide. Both these moments are echoed in Red Desert, in Mario’s apartment, when Corrado asks questions about the ‘woman in the clinic’: didn’t she feel a sense of attachment to her husband, or to her son?

The pragmatic, patronising tone of the interviewer in ‘Attempted Suicide’ has something in common with Corrado’s ‘be reasonable now’ attitude when probing Giuliana. But if the earlier film hinted at a level of insight, in the interview subjects, that was unavailable to the interviewer himself, in Red Desert this is more than a hint: Giuliana seems to have glimpsed a profound truth through her near-death experience, and one that Corrado cannot quite access.

To be clear, I do not think that Antonioni is extolling suicide as a way of grasping the mysteries of the universe. Indeed, I would reiterate that it is not suicide that interests him, but rather the notion, and the experience, of self-annihilation, which takes many different forms throughout his filmography. Rosetta in Le amiche unambiguously dies by suicide; Aldo in Il grido may or may not intentionally end his life; Anna in L’avventura may or may not even be dead; the characters in L’eclisse and Blow-Up simply disappear; Mark in Zabriskie Point, David in The Passenger, and several characters in I vinti go more or less willingly to their own (sometimes off-screen) deaths; Daria in Zabriskie Point, Niccolò in Identification of a Woman, and Antonioni in Lo sguardo di Michelangelo picture themselves as driving, or flying, or limping into the sun, in a way that suggests a flight into oblivion; the director in Beyond the Clouds withdraws into the darkness of his hotel room while (perhaps paradoxically) philosophising about exposing reality.

Antonioni frequently draws a link between self-annihilation and failed attachments. Ending one’s life, or assuming another’s identity, or blowing up a mansion and driving into the sunset, are just some of the spasmodic impulses through which people might respond to the malattia dei sentimenti that these films explore. This sickness is defined by a sense that love has gone wrong, that one’s partner, friends, children, colleagues, audience, or government – or even the subjects of one’s art – have ceased to be ‘relatable’, that one no longer ‘feels’ them, as Anna no longer feels Sandro. Sam Rohdie frames Antonioni’s treatment of suicide in a way that recalls the discussions about mirrors, being oneself, and being someone else that we found in Pavese and Visconti in Part 17:

Suicide, which is a kind of imagining of yourself as no longer and an acting out of your own obliteration, is an imagining both of death and of yourself as an other; it is a situation in which identity is uncertain, the line between being subject and object quivers, and all meanings and their location are made ambiguous.4

Rohdie’s phrasing draws a link between suicide, role-playing, and looking at oneself in the mirror, but it also suggests the central importance of relationships in Antonioni’s treatment of this theme. For the ‘line between subject and object’ to be compromised might entail a commingling of subjectivities, a romantic dissolution of one’s self into that of another; but in Antonioni’s world, it entails a dissolution of one’s self and the other’s self into objects that have no subjectivity, that cannot feel each other at all.

Giuliana’s attempted suicide comes to light in the context of a discussion about her (desired) connection to things that are sottomano, those tangible things that are physically attorno, but which she can no longer sense. Throughout the SAROM sequence, she is surrounded by objects and structures that seem especially ‘unrelatable’ (the de-humanised steel island, the all-assimilating ocean behind it). In the moment when she refers to self-destruction she dashes outside the film image: she ceases to find a place among these filmed objects. This ‘disappearance’ is another variation on the pivotal moment in L’avventura, when Anna, hiding herself amongst the rocks of Lisca Bianca, dissolves into the sea.

‘[T]he human figures in the foreground reveal their transience by disappearing from the frame,’ says William Arrowsmith, ‘and the world that was once background becomes the subject.’5 In this formulation, it is not Antonioni or the camera making the statement, but the character themselves. It is as if Anna and Giuliana were saying, ‘Look at this image of me, and now look at this same image without me – the sea, the rocks, the grey metal that were previously “background.” What does this say about what I am, or what you are, or what we are to each other?’

Unlike Anna, Giuliana immediately walks back into frame in the next shot. Having previously huddled among white/grey structures, she now stands exposed to the elements, framed against black cables, pipes, and the rectangular frame she stood behind earlier.

The blackness of these objects matches her black coat and is thrown into relief by the light beige of the ship in the background and the ever-present grey of the sky and ocean. It is obviously appropriate for a sudden burst of funereal darkness to accompany the moment when death enters the conversation, but the image here also continues to develop the motif of ‘connectedness’ that dominates this sequence. Giuliana appears caught in a network of ‘ties’: black cables that merge into her black coat but that seem tenuous and unstable as they sway in the wind; in the background we see tendrils of rope flapping about, matching the chaotic movements of Giuliana’s red hair. These things are literally ‘what she has around her’ in this image, but they also reflect the literal and metaphorical circumstances of her life. These are the kinds of objects, and the kinds of relations, among and within which she lives.

When Giuliana was framed against the antennae at Medicina, the red girders of that structure seemed to reflect something about her inner state – her troubled nerves projected behind her as she claimed to be ‘very well’ – but they were also the cold metallic blood vessels of her robotic surroundings.

The equivalent image on the SAROM island occurs in a subtly different context. The earlier sequence was more focused on Giuliana’s inner state, while in this one the emphasis falls more heavily on the things around her. There is a natural progression from the earlier discussion of her (supposedly) dysfunctional way of loving everything-at-once, to the current discussion of her (supposedly) dysfunctional desire to travel with everything-at-once.

When we saw Giuliana framed against the red girders, she was talking to Mario, and now she refers to him again, explaining to Corrado that he was another patient in the clinic who was ‘very ill.’ Corrado asks, hesitantly, whether Mario also tried to kill himself. Giuliana shakes her head and says, ‘No – him, no.’ Corrado observes that Mario must have recovered, since he has returned to work. Giuliana nods, looks at Corrado, then lowers her eyes and walks towards him, once again leaving the frame empty.

In the encounter with Mario, Giuliana seemed quietly devastated by the recovery of her former friend and by the seeming necessity to declare herself ‘very well.’ When discussing this with Corrado, she seems to feel the same things again. She presumably brings Mario into the conversation to draw a connection between herself and him, but Corrado’s comments only serve to reiterate the contrasts: Mario was not suicidal, Mario recovered, Mario is back at work. Giuliana visibly retreats back into her shell, glancing at Corrado with a now-familiar ‘misunderstood’ look before ending the conversation. Like Mario, Corrado asks Giuliana how she is now, and again she lies and says ‘well.’

The moment is in stark contrast to the one in ‘Attempted Suicide’ when the interviewer asks a woman, ‘But now you’re happy, no?’ and she replies, ‘Now, yes,’ smiling earnestly, as her new (rather stone-faced) lover stands behind her.

The moment in Red Desert is, however, true to the overall tone of this encounter in ‘Attempted Suicide’, which creates a haunting sense of things left unsaid, or of things that are unsayable in this context. The interviewer’s mind-numbingly common-sensical attitude seems to operate on a different plane from the imagery of the preceding sequence, in which this woman re-visits both the site of her suicide attempt and the feelings that accompanied it. She descends a vertiginous set of steps to the river-bank, far below the bustle of civilisation.

The film is called Love in the City, but here we see failed love driving a person beneath and beyond the city, into a river that flows through many cities. The woman finds herself in a place where land seems to merge into water.

‘Did you jump?’ asks the interviewer. ‘No, I walked in slowly,’ she replies, staring into the abyss of the water.

The camera itself then floats into this abyss, repeating her near-death journey. At first, the water that fills the frame reflects dazzling sunlight, but as the camera travels the sunlight disappears and we see only murk and shadows.

We home in compulsively on a rippling eddy at the corner of the bridge abutment: it is like the eddy that pulled this woman down and almost killed her. We are made to stare at it for several seconds.

After being immersed in this first-person drowning simulation, how do we respond to the interview subject’s performance of wellness, set against the artificial backdrop in the studio? This is a sad story with a happy ending, showing that one can sink to the lowest point and still recover, but even in this most redemptive part of ‘Attempted Suicide’, there is a premonition of the bleakness of Red Desert. The journey out of the city, out of the earth, into the oblivion of the Tiber, is hard to forget. Perhaps it becomes even harder to forget in those moments when it is hardest to describe – when some ostensibly well-meaning person asks, ‘But you’re okay now, right?’

After Giuliana nods and walks towards Corrado, we cut (for the second time during this sequence) to a shot of seagulls flying over the ocean.

We then cut to an overhead shot in which we see Giuliana nod at Corrado and walk towards and past him, before turning back to look at him.

Then the camera is looking over Corrado’s shoulder as Giuliana walks past him, and she looks back at him as he asks her how she feels now.

Once again, the film disturbs its own continuity: does Giuliana nod twice, and turn back twice, or are we seeing the same actions from different angles? Are these sincere and spontaneous gestures or choreographed movements within a fictional narrative, performed and filmed multiple times before being edited together? Obviously they are the latter, but why in this moment does Red Desert want us to become conscious of its fakeness?

The artificiality of the acting in this scene is thrown into relief by the shots of seagulls winging freely through the air. These images remind us that the SAROM island intrudes upon a natural habitat. There is a correlation between the birds’ restless flight (we never see them land or perch anywhere on the rig or the ship) and the sense of landless-ness described by Giuliana. At the end of the film, there will be a similar correlation between Giuliana and the birds who have learnt to avoid industrial pollutants. In the final image of the SAROM sequence, we see Giuliana trying to disembark from this artificial island.

When we next see her, she will be dreaming of a very different kind of island – one that is more real, more ‘natural’, but that is at the same time a complete fantasy.

Antonioni’s unmade film, The Crew, was to be set largely at sea, and to revolve around a central character who has gone missing and is thought to have drowned himself. But suicide in this case seems unlikely, as the narrator says:

I don’t believe that a man who owns a boat like that […] on which he spends the most carefree hours of his life, a man who loves the sea – I don’t believe that a man like that who wants to die chooses the ocean as his means of dying. A man like that knows that in death at sea there’s an instant when the whole world takes on the color of the wave that smacks you in the face and smothers you. And he knows that at that instant he’ll hate the ocean. No, that isn’t the feeling a man like that chooses to die with.6

This makes me think of the woman in ‘Attempted Suicide’ who walks into the Tiber, and of Rosetta in Le amiche who drowns herself in the Po.

In Gente del Po and ‘That Bowling Alley on the Tiber’, Antonioni sees these rivers as defining features of place: they may pass through multiple cities but they represent something elemental and inescapable about the locations or the ways of life being portrayed, including the inescapable transience that surrounds the Po with fog or that Giuliana evokes when she says, of the ocean, ‘it never stops, never, never.’ Unlike the protagonist of The Crew, those women may have wanted to end their lives in the river because they already hated it, and hated what it represented: the unceasing instability of here-and-now, the ambiente (physical, historical, social) in which they find themselves trapped. This was after all the motive of the child-murderer in ‘Bowling Alley’, who wanted to save his victims from the miserable life they would inevitably have in this place.

In The Crew, there was to be a moment when the hero, Powers, found himself piloting his beloved boat while under threat of death from the other people on board. Antonioni describes the character’s feelings as he watches the sea passing beneath him:

This direct contact with Nature encourages him after the depression that [overcame] him spending all day locked in the little cabin in the bow. It reinvigorates him, like food and water. Powers feels as if he’s a part of Nature too. Beneath him, the fish engage in their struggle against each other, as he too must fight against his own kind above. The laws of Nature are the same for all.7

Like the Tiber and the Po, the sea here embodies an essentialist conception of ‘Nature’ that is ‘the same for all,’ a universal truth about what it means to be alive, including the ugliness and terror of the conflicts between all living creatures. At the end of the story, upon returning to land, Powers imagines resuming his banal everyday life, but recoils from this and decides to become a homeless drifter instead:

As he walks off, he thrusts his hands into his pockets, walking into the darkness with the swaying gait of a man who is used to the sea.8

Powers is one of those Antonioni characters – they are usually men – who are ‘used to the sea,’ who arrive at a sense of harmony with the world they live in, and who allow themselves to be happily absorbed into a state of oblivion.

There is an instructive contrast between this serene renunciation to Nature and Giuliana’s suicidal impulse. Powers sails his boat on his beloved ocean, Giuliana drives her car into traffic or into the sea. When Giuliana looks out from the SAROM oil rig, the flocks of seagulls are like the shoals of fish in The Crew, an emblem of Nature following its universal laws, except that here the presence of the oil rig seems disruptive, and the birds’ restless flight seems to mirror Giuliana’s unhappy relationship with her own environment. Powers, disgusted with the civilised life he has built up for himself, is moved by his near-death experience to give that life up, but in so doing he seems to find a state of equilibrium with the universe. Giuliana’s walk into the darkness, as we will see in Red Desert’s penultimate scene, is quite different. Notice how, in the SAROM sequence, she goes from shielding her face behind her collar, to secreting herself amongst the machinery as she tells the true story of the incident, to rushing out of that composition to stand in the open.

She will never be ‘used to’ these elements that surround her – the man-made or the natural ones – but as such she has a kind of power that Powers does not. The laws of Nature are not the same for all, she seems to say as she tells Corrado what has happened to her. This encounter troubles him, in ways that will be obliquely suggested in the next scene.

Next: Part 27, Briefing the workers.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 481

Rifkin, Ned, Antonioni’s Visual Language (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982), p. 41

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 109

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), pp. 106-107

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 54

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Four men at sea’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 55-64; pp. 58-59. A more concise version of this sentiment was included in the longer treatment for The Crew: see Unfinished Business, p. 186)

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The Crew’, in Unfinished Business, trans. Andrew Taylor (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 181-196; p. 194

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The Crew’, in Unfinished Business, trans. Andrew Taylor (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 181-196; p. 196