Everything That Happens in Red Desert (27)

Briefing the workers

This three-minute sequence shows Corrado completing another preparatory task for his South American project. He and a colleague hold a meeting, in a large warehouse, with just over 30 workers who have been recruited for this job. There is a clear power imbalance between the two men who lead the meeting and the 30 men listening to them, and much of this sequence is focused on exploring the dynamic between them – the different perspectives, the nuances of the question-and-answer session, the emotions simmering beneath the surface – but like the camera itself, this focus drifts as the scene goes on, giving way to a roving fascination with objects and patterns in the warehouse. Although Giuliana is absent, the scene ends up being about her condition: how Corrado is thinking about it, how he is affected by it, and how the film itself is exploring the nature of Giuliana’s perspective on the world.

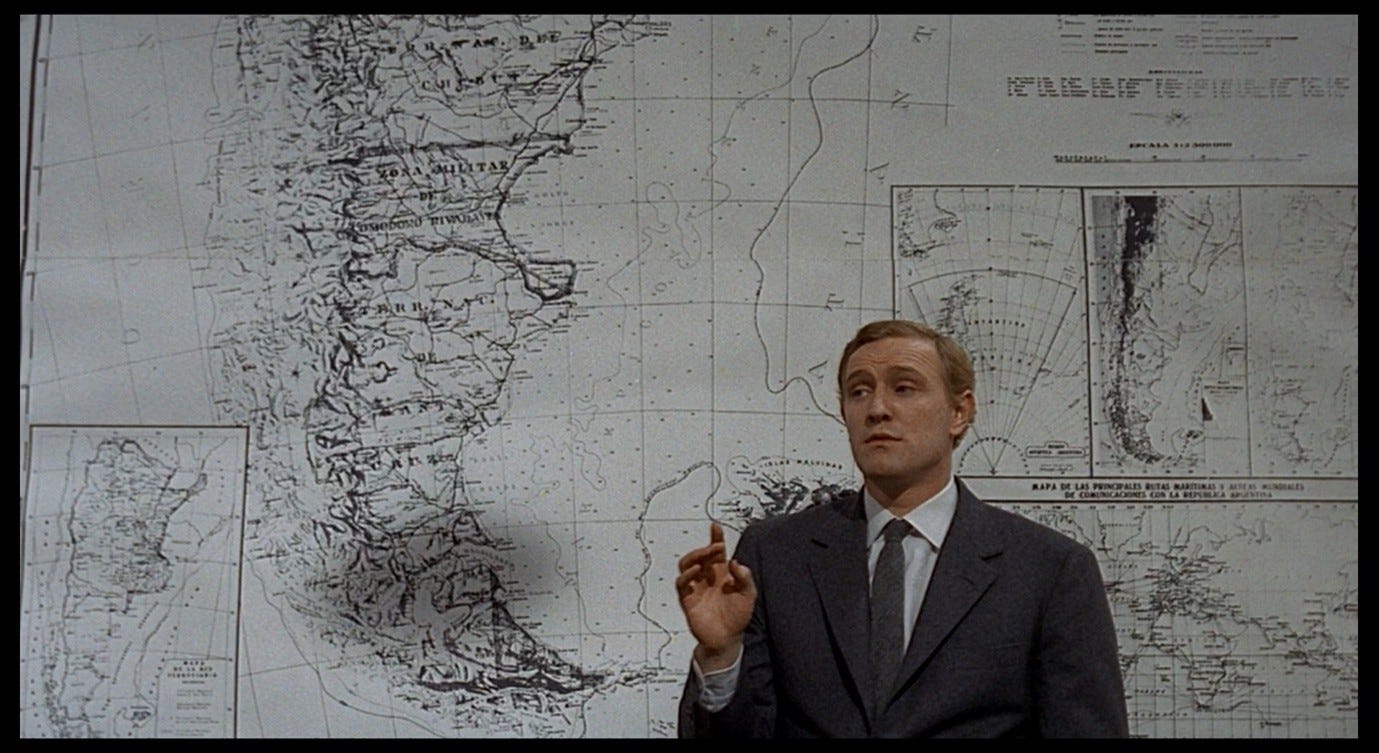

In the previous scene, we were inescapably conscious of the sea’s presence at all times, either because it filled the frame, or because it loomed large in the background, or because we could hear the waves beating against the pylons of the SAROM island. We now transition from the literal sea to a representation of the sea, and from the noise of crashing waves to complete silence. As we cut from Giuliana trying to leave the rig, a huge map of Argentina fills the screen.

The topographic lines on this black-and-white map make it harder to tell where the sea ends and the land begins, so that – like the wall at the start of the Via Alighieri sequence (discussed in Part 12) – the image is not instantly comprehensible. At the same time, there is something hyper-rational and analytical about it. On the right-hand side, under the title ‘Map of the Argentine Republic’, there is a key to aid interpretation, and beneath that there are smaller maps showing other kinds of useful data, some magnifying specific islands or regions, others taking a larger perspective to show the Americas in their entirety.

As in the Via Alighieri sequence, the arrival of Corrado brings clarity to the image, and in this case he is literally explaining it to us (‘As you see...’). The camera tilts down to find him using one of the mini-maps to comment on Patagonia’s proximity to the South Pole. His hand then ranges across the map to outline the route by which the project team will reach their destination.

In this opening shot, our whole attention is occupied by Corrado’s enterprise. This trip and its objectives are all-consuming, and for the moment they are seen in rather abstract, remote terms. We are traversing the planet via a piece of paper on a wall, with the casual ease of a hand-gesture. Our perspective in this shot is not unlike Corrado’s: as we have seen, he is single-mindedly preoccupied with the logistics of his work and somewhat detached from its more ‘human’ aspects.

From this limited perspective, we switch to the exact opposite, a wide shot from high up in the corner of the warehouse, allowing us to see the entire setting.

Like the map we were just looking at, this sequence will show us the same location at different scales, through different lenses, and with different focal points. If Corrado’s map serves to contextualise his project and illustrate how the team will reach their destination, the camera’s mapping of this warehouse and its inhabitants will trace a different kind of transitional narrative. Corrado’s fixation upon the South American project is wavering, and something else – something that cannot be illustrated on paper, but that is also more tangible and ‘human’ – is preoccupying him. The succession of moving images in this sequence will convey a sense of Corrado’s altered engagement with the world around him.

In his previous film, L’eclisse, Antonioni carefully establishes a series of spaces and objects around Piero and Vittoria when we see them together.

At the end of the film, we find that although these spaces and objects are firmly associated with the film’s characters, they resonate differently in the characters’ absence.

There is something of this technique in the briefing sequence in Red Desert. The wide establishing shot of the warehouse seems to show a setting with people at the centre and numerous inanimate components around them; but as the scene goes on, we will find our attention drifting away from the people and fixating on those inanimate components. What do these objects mean when we look at them in a way that obscures, erases, or object-ifies the nearby humans?

There are eye-catching wicker baskets piled haphazardly around the walls. They occupy almost every part of the wall except for the doorways and the space where Corrado and his colleague are standing. In one corner is a work-table that is presumably used to weave the baskets; it seems comically small given the hundreds of baskets that fill the room. We may notice a cluster of baskets made from wooden slats, standing out among the woven baskets at the far end of the room. Positioned nearer the centre is a more orderly stack of baskets, most of which are occupied by blue glass demijohns (as we will see more clearly later), but some of which are yet to be filled. Nearby there is a cluster of empty baskets, overturned to provide seating for the workers. In one glance, we see the labourers, the space in which they work, the machine that facilitates their work, the products they make, and the uses to which these products can be put. Even the unintended usage of the baskets (as seating rather than as containers) serves the needs of industry: this space, like the SAROM island, seems designed for entirely work-oriented living.

In Antonioni’s next film, the short segment ‘Il provino’ from I tre volti, there is an overhead shot of the film studio that resembles that of the warehouse in Red Desert.

We see the vast, empty space surrounding the closed-off film set where Princess Soraya’s screen-test is to be filmed: the three walls of this set are propped up by poles, there are lights around the top of these walls and more lights to one side, as well as strange contraptions we will later discover are wind-machines. As in the warehouse, we then cut to a low-angle view from the other side of the set, looking into the carefully constructed filming space that was not visible from our previous position.

From the high angle, the set is nothing – a whitish box in the middle of a desert – but from the lower angle, it almost fills the screen. As the camera dollies forward, the wall-edges disappear and we have the impression of being inside an opulent living room in somebody’s home, as though we were now watching the film Soraya is supposedly acting in.

The operative word is ‘supposedly’ because this is only a screen-test, not a scene in an actual film. This adds an extra layer to the illusion: the crew are pretending to film a scene in which Soraya is pretending to play a role. (Moreover, this is a ‘scene in an actual film,’ carefully directed by Antonioni.) Later, we will see the set from another vertiginously high angle, with Soraya taking her place among a set of triangulated light panels, pinned down by them like a butterfly in a glass case.

As in Red Desert, Antonioni is taking a huge space and making it seem strangely claustrophobic. Both the warehouse and the film studio have been constructed with a singleness of purpose that makes them unsettling. They represent the operations of two different industries that are bent on creating sealed-off environments in which control can be exerted over every aspect of the perceptible world and the behaviour of those who inhabit it. The film viewer must see the constructed and decorated set as ‘the world,’ and be completely absorbed by the equally authentic-but-illusory performance of Soraya. But by making a film about a screen-test, Antonioni asks us to see and reflect on the workings of this illusion.

The similar camera set-ups in Red Desert have a similar effect on the portrayal of Corrado’s meeting with the workers. Those workers are like a cinema audience watching a screen – the map of South America – and being inducted into the new reality that is to constitute their existence. When we see this meeting in context, from a corner of the ceiling, the empty space around it, coupled with the excessively copious stacks of baskets, makes the Patagonian enterprise seem like Soraya’s screen-test: a misguided folly that induces fear and loneliness in everyone involved. It is as though the camera were repeating Ivana’s question to Aldo (in the story, ‘A film to be made or not made’) when she says ‘Do you see that it makes no sense?’ (see Part 16).1 This is the question echoing inside Corrado’s head as he addresses his audience. Like Soraya, tasked with performing for the camera (and the audience), Corrado will quietly experience a breakdown in his relationship with his work. Both characters struggle to inhabit their assigned roles as they see this artificial world dissolving around them.

The barrenness and dilapidation of the warehouse are also striking, and in this sense the space differs from the industrial settings we have seen before. Baskets and glassware are antiquated artisanal crafts, like the ceramics Giuliana wanted to sell in her shop. The faded walls and floors of this warehouse, bearing old scars where structures or cables used to be, with a single light-bulb dangling overhead, subliminally remind us of that first conversation between Giuliana and Corrado in her shop, just as the impassive, resentful faces of the workers will remind us of the fruit-seller Tanino.

The daubs of colour on the walls of Giuliana’s shop are echoed here by the white square, surrounded by a dark blue outline, on the far wall of the warehouse, which stands out from the predominant light blue (celeste, one of Giuliana’s preferred colours). Presumably this square section of wall once served a purpose or housed a piece of equipment, but now – like the grey fruit-cart and the polluted ponds – it no longer ‘is’ what it used to be, and has come to resemble a work of abstract art, a kind of inverted International Klein Blue painting with a central white void and a vivid blue frame.

One of the workers interrupts Corrado’s speech to ask what the housing in Patagonia will be like, and this question is immediately followed by a cut to another perspective: we now find ourselves among the workers, hearing one of them ask a different question about payment.

Our first perspective in this scene could be called that of ‘the project,’ entirely absorbed in the map. Corrado’s voice brought the camera tilting down to his level, to provide a second perspective. The wide shot then gave us the perspective of a neutral, fly-on-the-wall observer. And when the workers begin to speak, we are brought to their level. Again, the project and Corrado look different from this perspective. They are not small and insignificant, but remote in a different sense. Our point of view is noticeably lower now, and the part of the frame we occupy is noticeably darker and more crowded than the bright, open space Corrado occupies. No sooner have we assumed the perspective of an employee than we find ourselves being (literally and figuratively) overshadowed and talked down to, as Corrado’s colleague holds up an admonishing hand and tells the audience to ask one question at a time.

The fact that a worker interrupts the presentation, and that a second worker interrupts the first, and that they are immediately asked to conduct themselves in a more orderly fashion, creates an atmosphere of muted unrest. We were first made aware of the industrial workforce through their (again, rather muted) strike action at the start of the film, so we already associate them with discontentment. Corrado’s somewhat unscrupulous efforts to recruit Mario, and to persuade Mario’s wife of the benefits of the Patagonia job, underlined the exploitative power dynamic between managers and workers. Now Corrado is once again pitching the enterprise to a crowd of underlings who, unlike Mario, no longer seem to have a choice as to whether they join the project or not. Nonetheless, they know their rights and guard them vigilantly. The workers are quick to dismiss Corrado’s irrelevant talk about the journey to Patagonia – the map seems distant and illegible from here – and they move the conversation to more important matters regarding their living conditions.

Peter Brunette argues that there is a sharp contrast between these issues and the ones that Red Desert is predominantly focused on:

The workers’ concerns are the exact opposite, and almost a parody of, the kinds of stresses that the middle-class characters, especially Giuliana, have been experiencing. Instead of worrying about their hold on reality, they wonder whether they will have access to television and sports newspapers, and how often they will be able to telephone their wives. Their concerns seem almost silly in light of the existential and psychological crisis that Giuliana is undergoing, but they have a specificity and substantiality for which Antonioni seems to be nostalgic.2

Specificity and substantiality are redolent of the ‘downright world’ that Nicole Diver ‘sought to make amorphous’ in Tender is the Night (see Part 23).3 As we have seen, Giuliana’s crisis centres on this conflict between the downright and the amorphous, between the kind of nostalgia Brunette invokes – a desire for the tangible and specific – and a longing to blur those tangible, specific things into one undifferentiated mass. I think Brunette overstates the differentiation between these two sets of anxieties, and that he misreads the tone of this scene when he says that the workers’ concerns seem ‘almost silly,’ or that they do not worry about their hold on reality. In Parts 28 and 29, we will see how their down-to-earth questions are juxtaposed (and connected) with images of both the workers and Corrado visibly undergoing precisely the kind of existential crisis Brunette sees as being reserved for the middle-class characters.

This meeting is a tense one and the changes in perspective make us feel this tension on both sides of the discussion. We now switch to a diametrically opposed point of view, facing the workers, as the first one repeats his question regarding accommodation.

We see the workers more or less as Corrado does, although we are closer to them (and more on their level) than he is: they look past the camera and slightly upwards as they address him. Our perspective makes us feel challenged by them, but perhaps more in sympathy with them than Corrado is. Earlier, when describing his philosophy of life to Giuliana, he proposed that one should believe in ‘socialism, perhaps’ and in ‘humanity, in a certain sense.’ There is something of this ambivalence in the way the camera treats the workers in the briefing sequence. Their resentment and suspicion towards Corrado are not unreasonable, and we are made to see him through their eyes; but we also see them through his eyes, as an anonymous, amorphous, and potentially obstructive mass. They care about themselves, not the work, and they have no reason to make this work easier for Corrado.

In both of the crowd-shots in this part of the sequence (which alternate with reverse-shots of Corrado), we can see the workers’ faces clearly, and each one seems individuated. In the first, the three most conspicuous figures are the two men in the front row – one young, anxious, and vulnerable, the other older, weary, and knowing – and the man asking the question about accommodation, who folds his arms and speaks with the cynical tone of someone who is used to being exploited. On the back row, we may notice a more aggressively resentful-looking young man who stares directly at the camera, and whom we will see again in a moment.

In the second crowd-shot, positioned further to the right, we have a similar gallery of differentiated faces: in the front row is an older man who looks worn down; behind him is a man wearing sunglasses with his arms folded defensively; further back, the one asking the question about pay is trying to sound reasonable, hesitantly making the case for giving the workers some small guarantee.

Not only do we get a strong sense of the exploitation occurring here, we also get a sense of how the workers respond to it in different ways. Some hope the bosses will be reasonable; some are losing that sense of hope; some lost it a long time ago; some are looking out for signs of exploitation and are ready to plead against it; some see nothing but exploitation and are ready to fight it; and some are numb and disassociated. In The General Line, the massed workers look ominously at the shifty priest who is conning them: their faces convey a unified spirit of protest, so that a single intertitle (‘Deceit?’) can speak for this whole series of images.

Red Desert shows a group of workers who all have similar concerns but manifest these in a range of different ways, and the film does not simply validate (or invalidate) the workers’ feelings. Perhaps the conditions in Patagonia will be good, perhaps they will not. The film does not adopt a political stance, but delineates the nuances of the dialogue between these men, the bosses, and their environment.

For instance, notice how Corrado’s colleague rebukes the second worker (who asks about money) by saying ‘one at a time!’, but then how Corrado repeats the same rebuke when this question is repeated after the first has been answered: ‘We’ll talk about that later, have patience, one problem at a time.’

Why can’t the issue of payment be discussed now – why does that question always have to be tabled for later? The initial rebuke comes to seem less like a reasonable request for orderly discussion and more like a disingenuous deferral of an issue the managers do not want to talk about. However many times you ask about pay, the response will always be, ‘one at a time!’ Unlike Eisenstein, Antonioni is not primarily expressing outrage at the injustice of this exchange, but using it as another instance of incommunicability, similar to the deflection of Giuliana’s difficult questions or the controversy over the cry outside Max’s shack. These disgruntled workers are not going to rise up in protest, or if they do the strike will be mild and will end fairly quickly. The miserable state of their relationship with the bosses is simply how things are, and the film’s job is to observe this in a way that suggests parallels with Giuliana’s story.

The light blue colour that pervades the walls (and the demijohns) may remind us that Giuliana wanted to use celeste and verde in her shop because they were neutral, non-disturbing colours. Antonioni himself cited the use of such colours in workplaces to maintain calm among factory workers (see also Part 7):

[S]tudies and experiments have been done about it. The inside of the factory in the film was painted red; in the space of two weeks, the workers on the set had come to blows. The experiment was repeated, painting everything pale green, and calm was restored. The workers’ eyes need to be soothed.4

In the briefing sequence, we can sense a relationship between the colour of the warehouse walls and the mood of those inhabiting the space. When the camera is positioned among the workers, the light-blue wall fills most of our vision, like an oppressive visual sedative.

There is a connection between the predominance of this blue in the frame and the vagueness of the shadowy, marginal space below (which we occupy). This warehouse is designed to placate us, just as Corrado’s answers are consistently placatory. As much as we feel the men’s resentment, we also feel how it is suppressed. Strikes are inevitable but inevitably fizzle out; these briefings are inevitably tense, but the project goes ahead anyway.

Next: Part 28, Shifting focus.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘A film to be made (or not made)’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 175-180; p. 178

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 101

Fitzgerald, F. Scott, Tender is the Night (1934 edition), ed. Arnold Goldman (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 270

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 294