Everything That Happens in Red Desert (37)

An incurable need

This post contains discussion of suicide and (after the row of asterisks) spoilers for Madame de… and Eyes Wide Shut.

The first thing Corrado does, upon welcoming Giuliana into his hotel room, is to ask after her son. She tells him the good news about Valerio and the bad news about herself: ‘No, he’s fine. He doesn’t need me. I’m the one who needs him.’ She asks Corrado, ‘Tu non mi ami, vero?’ (literally ‘You don’t love me, true?’) and reflects ruefully on her own neediness: ‘It’s never enough for me. Why do I always need other people? I must be a cretin [crettina]: this is why I don’t know how to look after myself.’

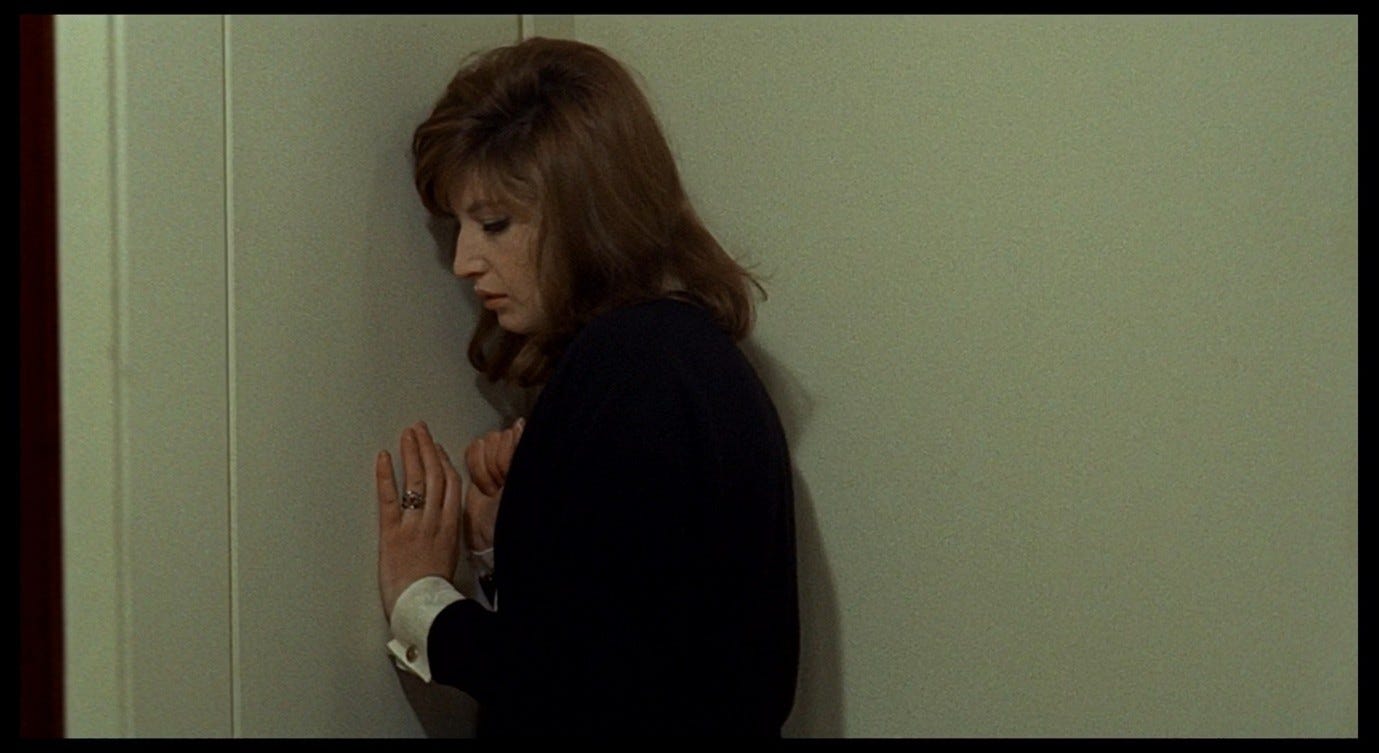

As she stands wedged into a corner of the room, she expresses her deepest wish: ‘You know what I’d like? All the people who have loved me…to have them all here, around me [intorno a me] like…a wall.’ Before now, she has described her illness in terms of her all-over-the-place love for and attachment to things and people, but in this dialogue there is something new about her specific focus on needing people. It appears to be this sense of need that brings her to the realisation that she is suffering from an incurable condition.

In Le amiche, Lorenzo is cheating on his wife (Nene) with the vulnerable Rosetta, who has recently attempted suicide. Near the end of the film, Nene ‘releases’ Lorenzo so that he can commit to Rosetta, and the two lovers find themselves alone in a dark, empty street in a depressed part of town. Rosetta is passionate and excited about committing to this relationship in earnest. ‘I know you need me,’ she tells Lorenzo.

But he backs away from her. ‘I have to tell you the truth,’ he says. ‘What truth?’ she asks, and for a long moment the camera lingers on her expression of dread. Lorenzo answers hesitatingly, as though confessing a shameful secret: ‘I...don’t need anyone.’ He walks away as Rosetta breaks down in tears and reaches out to him one last time.

Then she turns and walks the other way down the street, stumbling and sobbing all the way. A pianola plays deafeningly in the background, like a mocking counterpoint to her despair. After the fade to black, there is a jarring cut to Rosetta’s corpse lying on the bank of the river, covered in a white sheet.

Rosetta is a far less emotive character in Pavese’s novel, Among Women Only, and her suicide is not precipitated by a simple romantic disappointment. After Rosetta’s overdose, at the start of the novel, Momina questions whether it was even a suicide attempt:

‘[Romantic suicide is] no longer the fashion... Only servants or dressmakers’ assistants want to kill themselves after a night of love.’

‘A night and a day,’ said Fefé.

‘Nonsense. Three months wouldn’t have been enough. As far as I’m concerned, [Rosetta] was drunk and mistook the dosage.’1

The narrator, Clelia, offers another interpretation of Rosetta’s overdose:

At bottom it was true she had no motive for killing herself; certainly not because of that stupid story of her first love for Momina or for some other mess. She wanted to be alone [stare sola], wanted to isolate herself from the ruckus and you can’t be alone or do anything alone in her world [nel suo ambiente], unless you take yourself out of it completely.2

Shortly before the end of the novel (when she takes her own life), Rosetta argues that funerals should not be social affairs like baptisms and weddings:

‘[T]he dead ought to be left alone [lasciato solo]. Why keep on tormenting them? [...] People who committed suicide used to be buried secretly.’3

The causes of Rosetta’s suicide remain elusive to the end, but she is clearly sickened by the society she lives in, by the types of connections she has with other people, and by the activities in which they are engaged. As Clelia says, it is not so much that Rosetta wants to die as that she wants to be left alone, sola as in the novel’s Italian title, Tra donne sole. As long as she lives among the upper classes of post-war Turin, she will feel helplessly un-alone.

At first glance, the Rosetta in Le amiche seems an inversion of the one in Among Women Only. Far from wanting to be alone, she is fixated on her romantic attachment to Lorenzo, and losing him prompts her to take her own life. Lorenzo expresses something like the original Rosetta’s sense of jaded isolation when he says, ‘I don’t need anyone,’ but after her suicide he returns to Nene to re-affirm his deep need for her, begging her never to leave him alone. ‘Why do you still love me?’ he asks. ‘Perhaps because you cost me so much,’ she replies.

When Lorenzo claimed that he did not need anyone, was he lying to Rosetta to get rid of her, or was he exposing an uncomfortable truth that even he (let alone Rosetta) cannot tolerate for more than a few minutes? Is Lorenzo only ever playing at needing anyone – Rosetta or Nene – because that is the ‘done thing’ in his culture? Does Nene take him back at the end because she is disillusioned enough to tolerate this reality? Is living with that disillusionment the ‘cost’ she speaks of in her final line? Does she understand the nature of his condition – his inability either to commit to or abandon her – and does her pity for him transmute into love, as his more confused pity for Rosetta was easily mistaken for love? Does Lorenzo need others in the way that Sandro needs Anna, then Claudia, and then Gloria in L’avventura, compulsively and impulsively, almost as if these women were interchangeable? And is Rosetta’s suicide like Anna’s disappearance in L’avventura, and therefore not unlike the choice of Pavese’s Rosetta: a rejection of a world, and of a type of relationship, that sicken her, that (unlike Nene and Claudia) she simply cannot live with?

In Red Desert, Giuliana reads her son’s deception as a statement about their relationship, very much like Lorenzo’s confession to Rosetta. Valerio does not need her and perhaps does not need anyone. The context here is more primal. To live in a world dominated by people like Lorenzo and Momina in Le amiche, who use each other without any sense of real emotional investment, is depressing enough, but Giuliana’s world has gone beyond this. This child does not need his mother, and in a further inversion of the supposed natural order, she is the one who needs him. Her need, not only for her son but for anyone, is viewed (even by herself) as an aberration, a sign that she is a crettina, and the main reason why she is suffering a breakdown.

As Giuliana beats herself up in this intense display of internalised blame, we are left to consider the tension between her sickness and the sickness of the world around her. Is her son an exemplary member of the new and improved human race, and is Giuliana a weak, needy remnant of the previous evolutionary phase? Or is this need, including the need to be needed by others, a vital element of humanity without which we cannot survive? Are people like Rosetta and Giuliana simply not cut out for the demands of this world, or does their disintegration constitute an implicit critique of that world? For Antonioni as for Pavese, there are no simple answers to these questions. Giuliana’s condition may tell us that there is something seriously wrong with the world we live in, or it may be an inevitable (if unfortunate) by-product of human progress. We may take the side of that tinkling pianola that seems to say, ‘These casualties of reality are pitiable, but not to be taken seriously – life goes on.’ Or we may want to smash the pianola with a hammer.

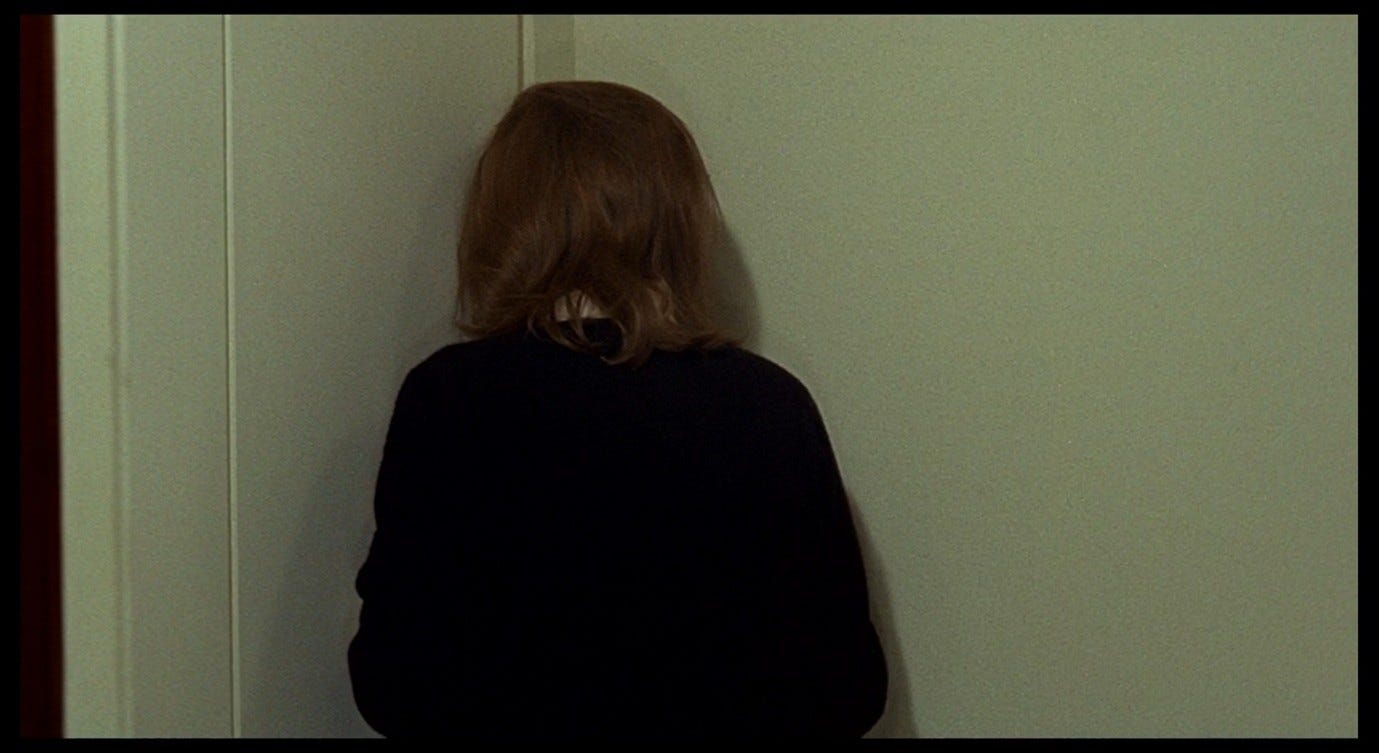

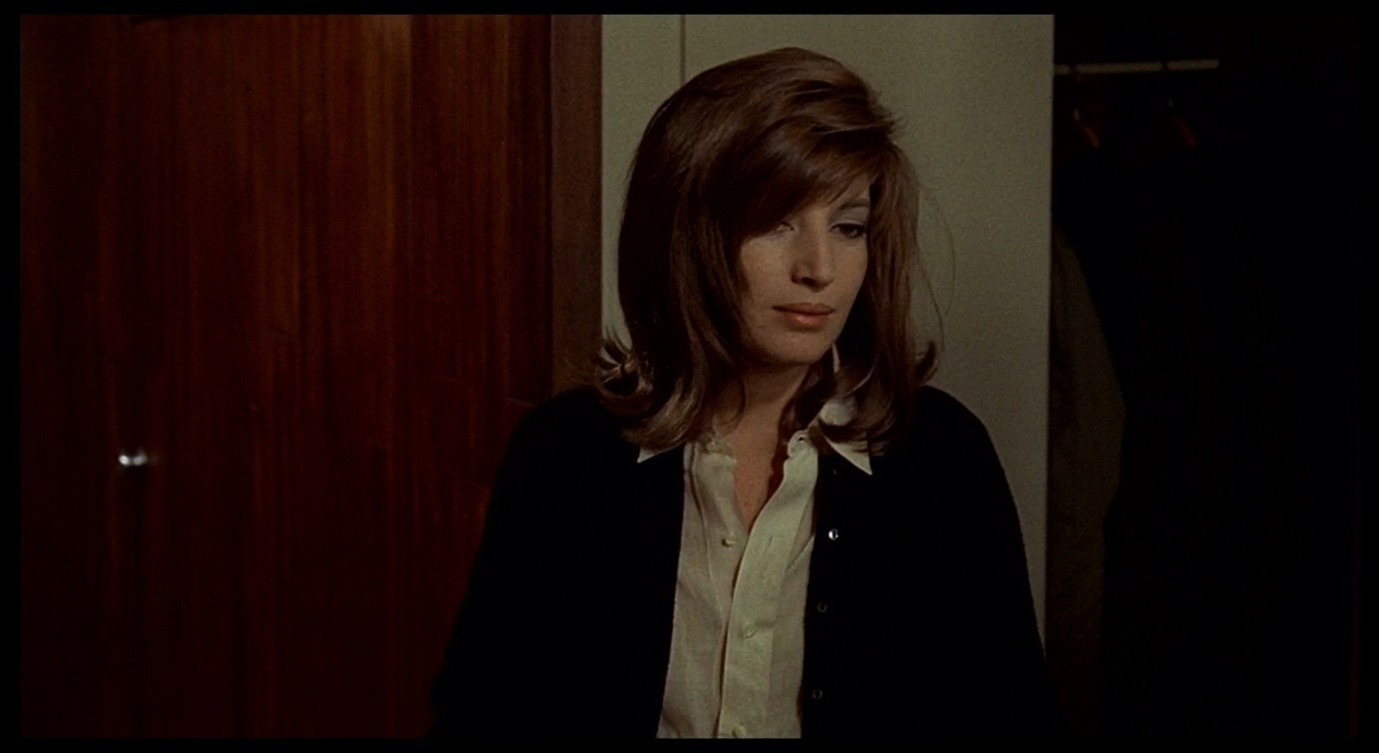

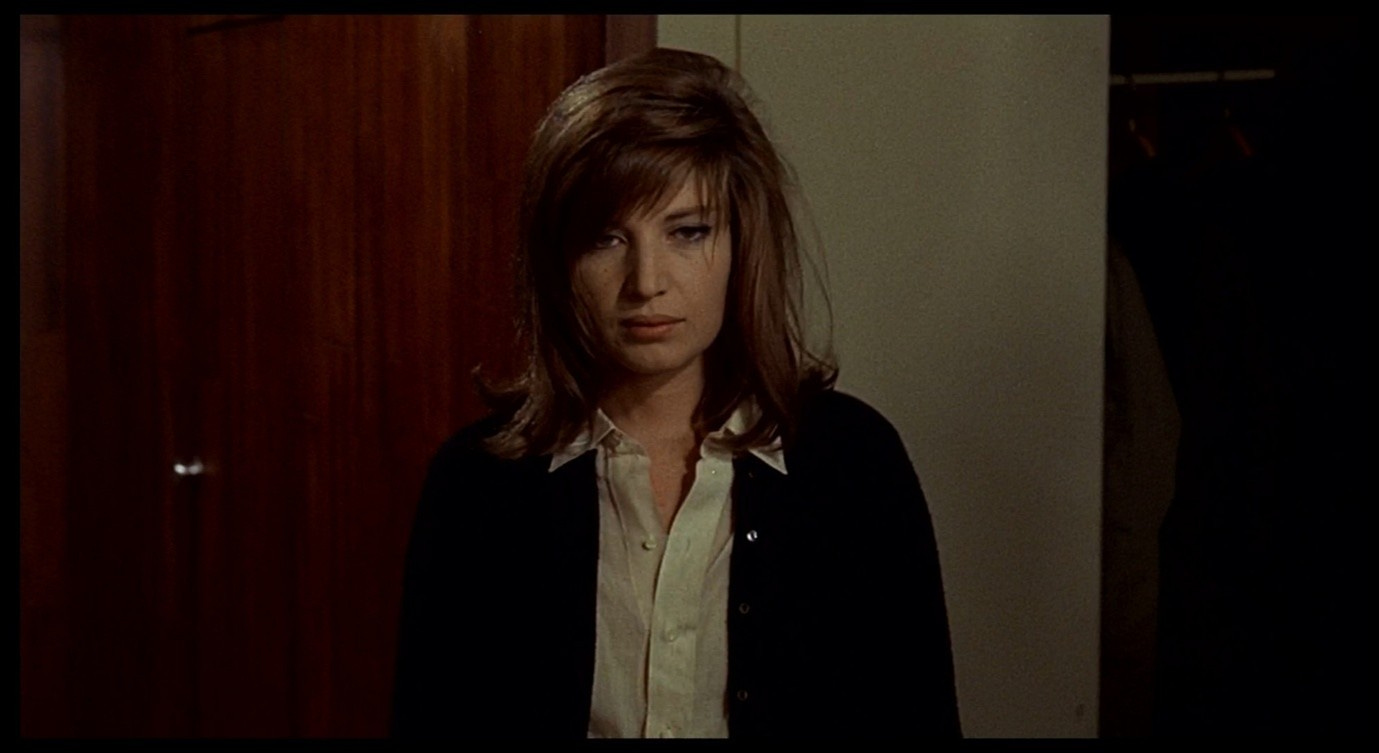

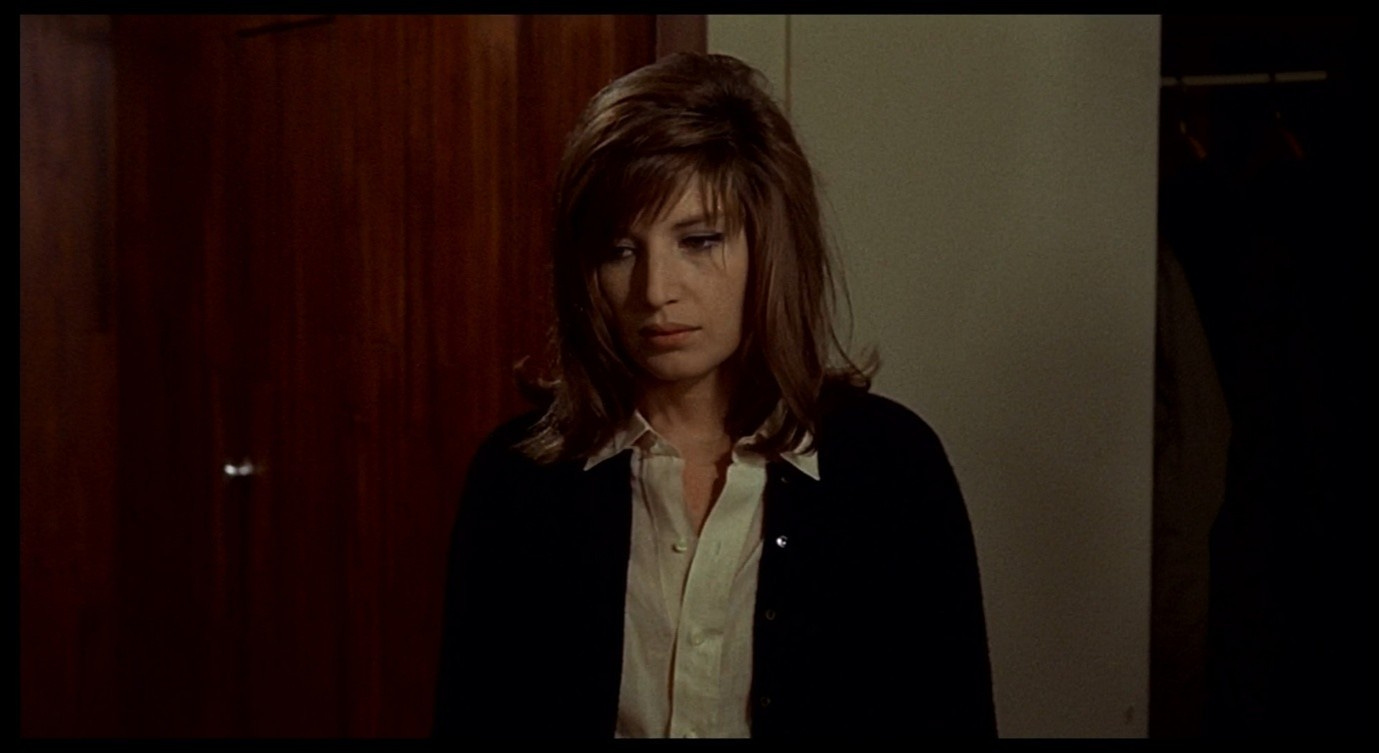

This is the dilemma Giuliana herself is dealing with. As she calls herself a crettina, she stands with her back to the wardrobe, whose open door obscures part of her face.

She then moves along the wall and hides her face in the corner, before half-turning to look towards Corrado, with her hands against the wall.

As in the hotel corridor, she is both clinging to the wall for stability and pushing against it in resistance. Her position also recalls the moment on the SAROM rig when she told Corrado about her suicide attempt, when she took refuge in a cramped nook of the industrial structure.

Here too Giuliana reveals a key piece of information: such moments often happen when she is backed into a corner or against a wall, as though she were trying to escape and had nowhere left to run, but also as though she had found a safe space in which she could hold onto something solid while revealing her most vulnerable thoughts.

When she says, ‘Do you know what I’d like?’, there is a tone of exhaustion in her voice. She is elaborating on her self-directed insult from a moment earlier – in a sense she is saying, ‘Do you want to know how much of a cretin I am?’ – but also expressing her deepest wish with a kind of relief at being able to put it into words. She speaks hesitantly, not unlike Lorenzo saying ‘I don’t need anyone,’ except that she is saying the opposite. Lorenzo was loved by two women and claimed not to need either of them, while Giuliana needs to be surrounded by everyone who has ever loved her.

There is a long pause as she says that these people would surround her ‘like...a wall [muro],’ and she hesitantly puts out one hand as she pictures this wall. She lingers over the word muro, savouring this fantasy of the many-become-one.

This is, I think, her definitive expression of how she loves other people, and again it captures a tension between amorphousness and solidity. She does not want to merge into her loved ones like a cloud, but to have them as a wall that surrounds her. There is a blurring of identities, and a blurring of the boundaries between animate and inanimate objects, but also a sense that she and the wall remain discrete and separate. In this fantasy, she is not only protected but also contained and isolated. This wall of love would keep out the rest of the world, so that like Pavese’s Rosetta she could be left alone; but like Antonioni’s Rosetta she also longs to never be alone, to always be held within the embrace of those who love her. The contrast with Guido Anselmi’s ring of loved-ones at the end of 8½ is very telling: he takes his wife’s hand and leads her into the ring itself, to become part of it, hands joined with the rest of the dancers as they begin their indefinite circular dance.

Giuliana does not long for a dancing ring in an outdoor circus, but for a still, solid wall; and she does not want to be part of the wall, but contained within it and (by implication) at a certain distance from it.

Rather than engaging with any of this, Corrado asks Giuliana what has happened. He evidently believes that something must have happened, if not to her son then to her.

But she snaps out of her fragile intensity into a more casual mode, walking across the room and shrugging as she replies, ‘Nothing – just imagine [pensa un po’]: nothing.’

This is in part a response to Corrado’s tacit dismissal of everything she just said. To him, her agonised fantasies are indeed niente, and the important thing is to identify the real-world event that has upset her. Giuliana adopts the matter-of-fact demeanour that Corrado wants to see, conceding that her breakdown is without cause. As she did in the clinic, she becomes another Giuliana, one who can explain to her unwell self that there is ‘nothing’ wrong, but now the well-splaining Giuliana speaks in a tone of half-comic resignation about her terminally sick alter-ego. The phrase pensa un po’ is like a shrug of despair: just imagine being so upset over absolutely nothing. What a lost cause this unwell self is.

In several earlier scenes, we have heard a sinister electronic whine accompanying Giuliana’s moments of crisis: her night terrors at home, her encounter with the grey fruit-seller, and most recently the exposure of Valerio’s deception. Similar noises occur intermittently throughout the hotel room sequence, building in intensity in tandem with Giuliana’s panic. Near the start of the scene, when she walks past a window and a yellow light suddenly comes on outside, a disturbing hum occurs at the same time.

In her ‘like a wall’ dialogue with Corrado, when she says, ‘Nothing – just imagine: nothing,’ the high-pitched whine starts up again with the second niente, and Giuliana’s face darkens.

The frightening noises in earlier scenes gave us an impression of the sensory world that Giuliana lives in, where the eerie sounds of mechanical or electronic objects resonate painfully through her mind and body. When she first enters Corrado’s hotel room, Giuliana says that her hair, eyes, throat, and mouth hurt, while tilting her head to one side as though she had a neck injury.

The painful vibrations on the soundtrack help us to understand what she means. Because we did not hear them for a while – between the Via Alighieri and Valerio’s ruse – they also spell returning danger, as if that monster she saw in the darkness during the night-terrors sequence had come back to menace her again. The monster appears in the form of Valerio, the yellow light outside, the atmosphere of the hotel room, and other manifestations that are harder to pin down. All this contributes to the climactic tone of the hotel room sequence, in which Giuliana confronts the monster more directly than in any other scene, and after which the film’s emotional intensity will subside.

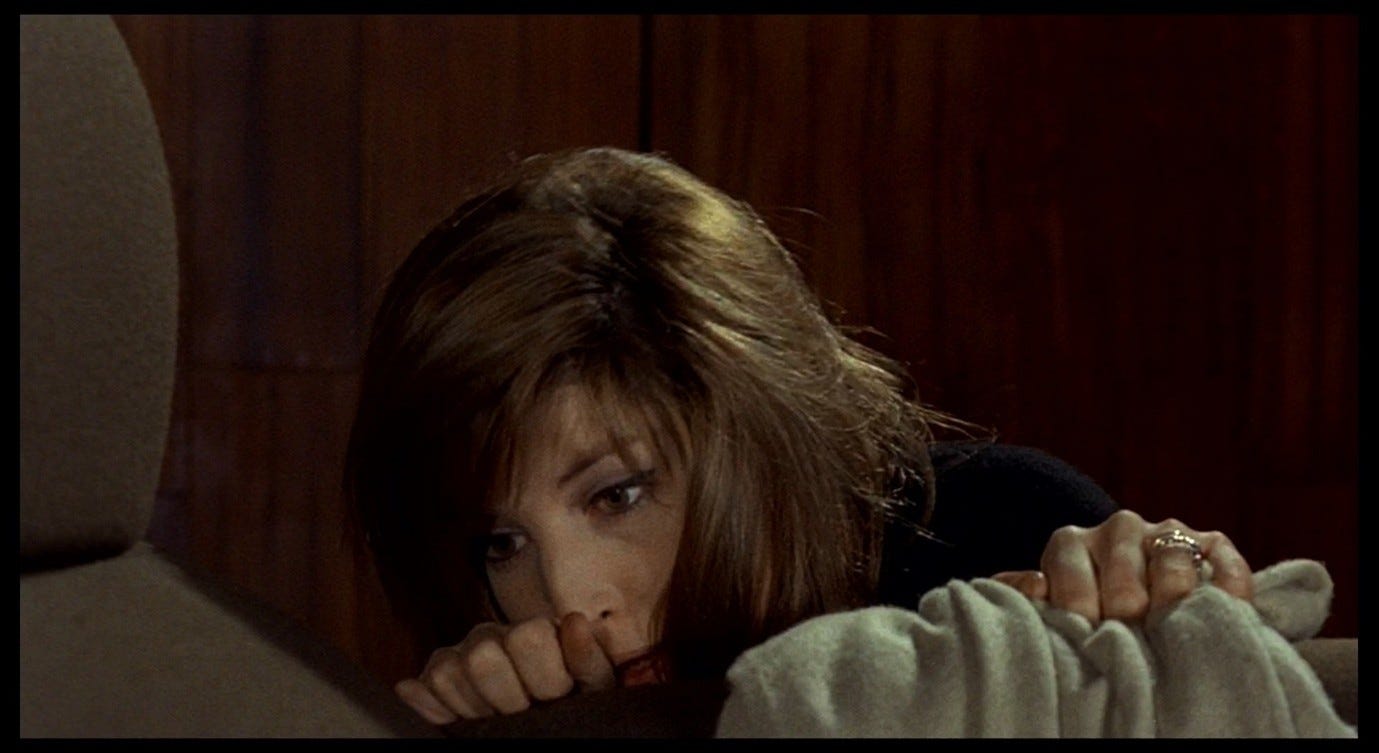

Her casual dismissal of her own sickness with the repeated word niente is undercut by the menacing hum on the soundtrack. When she hears this noise, her casual stroll across the room turns into something else. After looking at Corrado when she says niente, she suddenly turns away from him and walks over to an armchair. Rather than sitting down and continuing to speak calmly, Giuliana falls to her knees and clutches the arm of the chair.

Out of context, this composition might evoke an experience of loss or abandonment: a grief-stricken woman kneeling by an empty chair, the clothes and possessions of her absent loved one strewn about her. And in a way, this moment is about Giuliana’s loneliness. There is something about Corrado that she cannot connect with, so she turns away from him and finds another secret corner, an empty space where she can be alone and give voice to her feelings. Her collapse tells us that this is not niente, but it is also a reaction to that voice (the voice of the other Giuliana) that said niente. Giuliana lives in a world where the causes of her illness cannot be acknowledged, and this is one reason why, as she now says, she remains un-cured and incurable.

After lingering for a moment on the view of Giuliana from behind, kneeling by the chair and facing away from us, the camera cuts to a reverse-shot close-up of Giuliana’s face. She looks towards the area behind the camera and says, ‘I am not cured [Io non sono guarita],’ shaking her head slightly.

She seems sad and almost resigned. But as the screenplay says, ‘This lightning-bolt thought terrifies her, and another one quickly follows it.’4 She goes on, ‘I’ll never be cured. Never...never... [Non guarirò mai. Mai…mai…]’ The Italian verb guarire can be both transitive (‘to cure’) and intransitive (‘to recover’), and we should note the ambiguity here, between the feeling that one ‘has not been cured’ and the feeling that one ‘will never recover.’

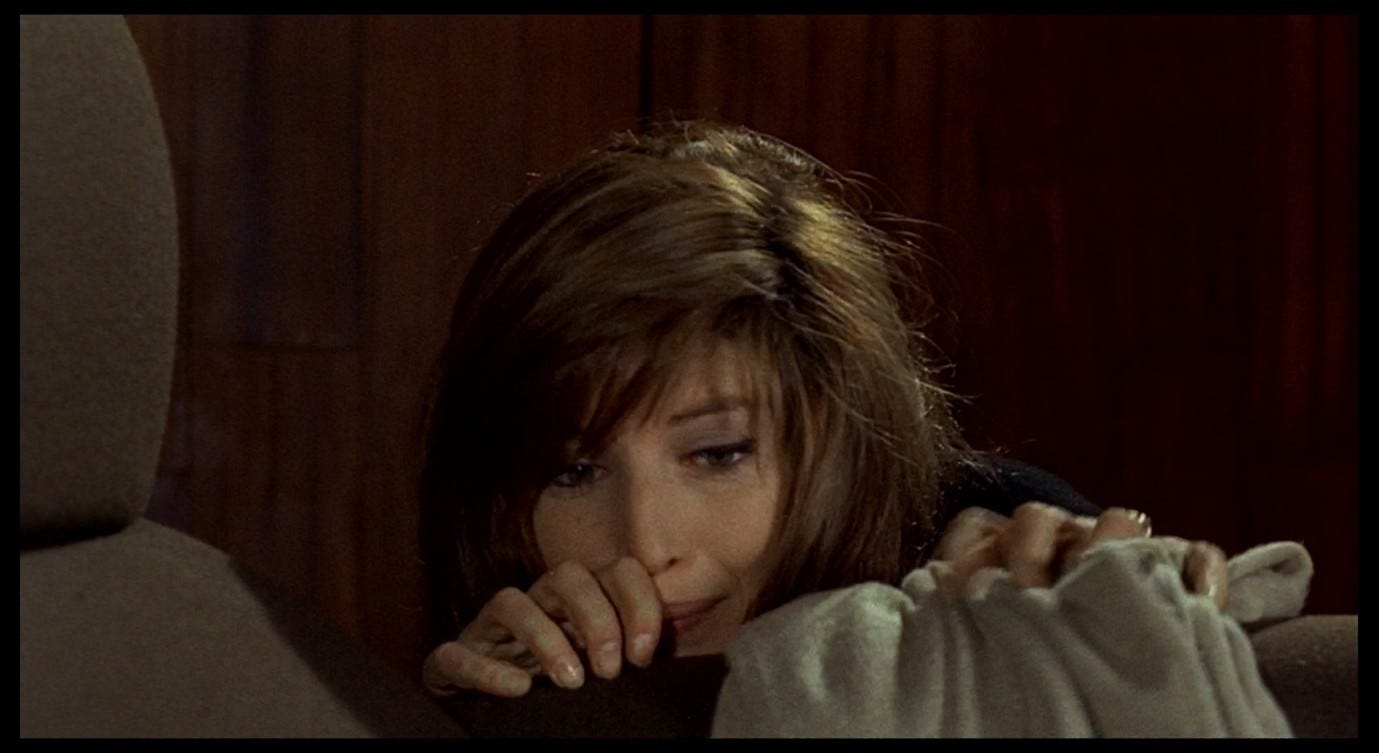

When Giuliana first says mai, her voice breaks slightly. The prospect of never being cured hits her for the first time, and we hear this from the audible sob in that last word. The shaking of her head continues and begins to seem involuntary, like the nervous trembling we saw when she spoke to the concierge. She buries her face in the arm of the chair again, perhaps to stop her head from shaking. She clutches desperately at the chair and at the shirt draped over it.

She repeats the word mai, and her face reappears above the chair, a look of frantic, animal terror on it as she looks off to one side and says mai again.

Her voice no longer sounds like a sob, but like a whisper. She is compelled to repeat the word as the realisation sinks in deeper and deeper, but scared to say it out loud because of what it means. The sinister noise on the soundtrack dies down but then rises up to a higher pitch, like a migraine subsiding only to return with greater intensity, or like a frightening idea being buried in layers of denial and then boiling up through the cracks. Giuliana’s gaze begins to dart around as she continues to grip the chair and say mai, only now this word (like il nome in the hotel reception) disintegrates into its component parts until it sounds like she is saying ma and io.

The ‘never-ness’ of her condition has several layers, which are all captured in this moment: ‘It’s nothing but I’ll never be cured’; ‘I’ll never be cured but I must go on living’; and there is also a cyclical tension between mai, ma, and io, where the ma functions both as a plea for relief (‘But I must have hope’) and a denial of relief (‘But I have no hope’).

This is the single bleakest moment in Red Desert. It conveys a similar idea to the line, ‘You can’t get rid of the Babadook,’ affirming that the mental illness from which Giuliana suffers will never fully disappear. This is a notoriously challenging concept to come to terms with, and a potentially dangerous one as it can engender an all-consuming despair that stands in the way of recovery. It is also, however, a dangerous idea not to talk about, to dismiss as niente or to drown out with pianola music. Giuliana’s armchair soliloquy feels bleak, not primarily because of what she is saying, but because she has to be alone in order to say it – because she does not say it to Corrado, and because (whether he is within earshot or not) he does not hear it or engage with it. Again, remember the emphasis on need in this sequence, on Giuliana’s dependency. She sees this as a sign of weakness and stupidity, but it can also be seen as a critique of her cold, unsympathetic environment.

William Arrowsmith describes Giuliana as being torn between a desire to protect herself from the poisons that threaten her world and a fear that the protection itself may be poisonous to her:

Her profoundest instinct is to build an unbreachable wall against everything that might change her world. […] But reality breaks through her screen. […] [D]espite her defenses, reality keeps intruding. No shelter is proof against it. […] But with another part of herself, […] she resists her instinct to find shelter – an instinct that, in her more conscious moments, compares to drowning, to sliding down a slope, or sleeping on quicksand. Offered the containment of physical love, she instinctively, with one part of herself, resists, even while she hungers for it too. […] Whether she is with Ugo or Corrado, she responds to physical love with desperate need but equally desperate fear – fear of somehow losing herself in their need, of becoming them, at the same time that she wants nothing more than the warmth and security of their being, to be part of them fused in a single identity.5

Arrowsmith claims that Giuliana’s ‘desperate need’ is partly a hunger for physical love, but I think the film pushes us to be more sceptical about this. Yes, she says she wants to make love in Max’s shack, and some of her gestures when interacting with Ugo and Corrado might perhaps be read as expressing a need that is specifically sexual. But those gestures are, I think, far more easily interpreted as ones of resistance, and her voglia to make love is not expressed as a desperate need. The connection, as described by Arrowsmith, between the desire for a protective wall and the falling/drowning sensations, captures something of the double-bind Giuliana finds herself in. I am not sure that her fear is of becoming Ugo or Corrado by having sex with them; rather, I think she fears confronting the discrepancy between her own needs and the perception of those needs (and of how they should be fulfilled) by those around her. What Ugo and Corrado express are not needs, and perhaps not even desires, but are more like interpretations or prescriptions. Her frustration with her own neediness is like that of a suffering patient, cursing themselves for having an illness that medical science can only treat in the most misguided, counter-productive ways.

Sequenze di fabbrica is a multimedia artwork composed by Adriano Zanni, consisting of a book of photographs – taken among the Ravenna factories where Red Desert was filmed – and five musical tracks incorporating dialogue from the film.6 In the second track, ‘Mi fanno male i capelli’, we hear Giuliana’s words in the hotel room scene, culminating in ‘I will never be cured.’ Leading into this moment, we hear a multi-layered drone, sinister but quiet, behind the dialogue. But after Giuliana utters the second mai, a loud, dramatic, low-pitched electronic chord breaks in, preceded (a split-second earlier) by a slightly quieter version of itself, as though we ‘saw’ the chord being struck some distance away but the sound took an instant longer to reach us. We are inhabiting the mind and body of a spectator – another spectator, not us – who is watching the film, sharing their senses as it resonates with them, though at a slight remove. Likewise, Zanni’s photographs are familiar from Red Desert but also new and different, in black-and-white, taken from different angles. ‘None of that profound vitality that Antonioni saw in the factories […] shines through the artist’s images,’ says Alberto Giorgio Cassani, not as a criticism but to acknowledge the deliberate difference between Sequenze di fabbrica and Red Desert.7 Those overwhelming orbs that Giuliana walked beneath as she made her way to the hotel are shown, by Zanni, from a lower and more human angle, revealing the orbs more completely and depriving them of some of their mystery. We can see the poles anchoring them to the earth and the bases of the ladders we could climb if we wanted to ascend these structures.8

But as in all the photographs in Sequenze di fabbrica, the industrial zone is deserted. An apocalypse seems to have taken place, draining the world of all living things. The dramatic chord after Giuliana’s second mai achieves a similar effect: it represents the terror someone might feel in watching the hotel room scene, just as the photographs represent the grey desert someone might find themselves in, emotionally speaking, after gazing into the red desert for two hours.

This is all the more powerful because it is so deliberately removed from Red Desert itself, despite being inspired by and (on the aural level) constructed from the film. Accompanied by Vittorio Gelmetti’s electronic score, Giuliana’s despair is underlined by a less dramatic high-pitched whine, which I have before compared to a tinnitus-whine because this suggests both its internalised nature – Corrado cannot hear it – and its pitiless indifference to its host’s suffering. Giuliana’s incurable need is like the need for that terrible ringing noise to stop. Hearing it slowly increase in volume as she clutches the arm of the chair, we feel her pain at the realisation that it will not stop; but in another sense we remain separated from her, and for us the noise does stop.

What Zanni expresses is the pain of that mingled empathy-and-separation. His dramatic chord resembles the one at the end of Identification of a Woman (see Part 35), following the nephew’s quietly devastating question, ‘And then?’ As such, it is cathartic in a way that Red Desert itself is not. Just as the chord in Identification expressed something of the taciturn Niccolò’s low-flame despair, so the one in ‘Mi fanno male i capelli’ affirms that this other kind of despair can be expressed, that an electronic chord can be found to match the feeling of suicidal depression. But whereas John Foxx’s music for Identification develops, over the end credits, into a sad but serene electronic song that eases us out of the film, Zanni’s note of devastation persists for an uncomfortably long time. He composes music to try and articulate the emotions the film elicits from him, but finds the music extending indefinitely and, in a way, turning back into the tinnitus-whine that coldly afflicts Giuliana. He visits the factories to try and see them as Giuliana did, but finds them inescapably different, his Ravenna rather than hers. ‘The bodies are separate,’ Giuliana will explain later in the film, to a man who cannot understand a word she says. ‘If you prick me, you don’t suffer.’ There are many ways to respond to this, including through beautiful and moving works of art, but there is no cure for it.

* * * * *

Giuliana’s line near the start of the hotel room scene, ‘You don’t love me, do you?’, carries an echo of Madame de…, in which the heroine says to her extra-marital lover, ‘But you don’t love me anymore, do you?’ In that case too there is no direct reply from the man, but it is apparent from Louise’s tearful breakdown that Baron Donati is still visibly in love with her, and that he will therefore go to his death in a duel with Louise’s husband.

Madame de… is a classic example of the kind of adultery drama Red Desert is invoking, with a cold high-status husband, a dashing but slightly hapless outsider, and a female protagonist suffering from painful emotional needs that her marriage (and her broader ambiente storico) cannot satisfy. There are tense interactions between the husband and the lover that anticipate some of the two-shots of Ugo and Corrado in Red Desert.

In Ophüls’ film, very little time is spent on fleshing out Louise’s relationship with Baron Donati. We can see very quickly that his light, easy manner is in stark contrast to the General’s military discipline and conformity. But as well as deploying short-hand and tropes, the film also comments reflexively on the narrative conventions into which these characters are slotted. ‘I never liked the character [personnage] you made me into,’ says Louise’s husband, as though finding himself in a fiction written by her. ‘I wouldn’t have chosen it.’

The word personnage also turns up in an earlier Ophüls film, La ronde, in the recurring song of the master of ceremonies: ‘Tournent, tournent, mes personnages,’ he sings as the characters whirl from one amour to the next, in an image of compelled, benign promiscuity that perhaps inspired the circus-ring at the end of 8½.

Ophüls, like Antonioni, is often drawn to characters who become self-aware about the larger structures they find themselves operating in, and who struggle with the conflict between those structures and their own needs and desires. At the start of Madame de…, Louise needs money and pawns her earrings; at the end, she needs Donati to live and gives her earrings away in an attempt to save him. The point is not so much that she becomes less materialistic or more pious, but rather that her need for human connection overrides all other concerns, to the extent that it ultimately kills both Donati and (when she learns of his death) Louise herself. ‘I detest the world,’ she tells her lover. ‘I only want to be seen by you.’

Like Giuliana, she experiences a kind of doubling of herself: ‘The woman I am suffers because of the woman I was.’ Her habitual way of life has been exposed as a prison, and the personnage to which she was assigned in this prison has, like her personnage-husband, become an enemy to her current happiness.

In Eyes Wide Shut, Stanley Kubrick’s most Ophüls-ian film (based, like La ronde, on a text by Arthur Schnitzler), a married couple is thrown into crisis by a confrontation with their own and each other’s suppressed adulterous desires. The wife, Alice, dances with a dashing Hungarian stranger named Sandor Szavost who looks somewhat like Vittorio de Sica (who played Donati in Madame de…), and although they do not fall in love the encounter triggers an argument with her husband about her capacity to desire other men.

In Schnitzler’s Dream Story, the husband reflects on his increasing sense of alienation after learning about his wife’s unknown inner life:

Strange how homeless, how rejected he felt […] [E]ver since his evening conversation with Albertine he had been moving away from the habitual sphere of his existence, into some other remote and unfamiliar world. […] [Fridolin] had the sense that all this order, balance and security in his life were really an illusion and a lie.9

Fridolin’s would-be illicit encounters with women, as he wanders the streets at night, are not like ‘experiences’ but more like ‘enchantment[s] that must not gain power over him,’ or fever dreams induced by sickness.10 This malattia dei sentimenti compels both him and his wife to want to cheat on each other, but with a desire that is always conflicted. When she describes her erotic dream, she is torn between two emotions:

‘[J]ust as that […] feeling of horror and shame transcended anything conceivable in a wakeful state, it would be equally hard to conceive of anything in normal conscious life that could equal the freedom, the abandon, the sheer bliss I experienced in that dream.’11

Fridolin imagines taking revenge on her by replicating this conflict in his own life:

[T]he idea of betrayal, lying, infidelity and a bit of hanky-panky here and there, all under the noses of Marianne, Albertine, the good Dr Roediger, all the world – the thought of leading a kind of double life, of being at once a hard-working reliable progressive doctor, a decent husband, family man and father, and at the same time a profligate, seducer and cynic who played with men and women as his whim dictated – this prospect seemed to him at that moment peculiarly agreeable.12

He goes even further, and imagines doing what Anna perhaps does in L’avventura, and what later Antonioni protagonists (in The Passenger and The Crew) would in fact do:

[H]e thought of driving to some station, taking a train to wherever it might be and vanishing from the lives of everyone who knew him, to resurface somewhere overseas and begin a new life as someone else. […] True, such things happened very rarely, but they had been authenticated none the less. And in a milder form they were experienced by a great many people. What about when one awoke from dreams, for example? Of course, there one could remember … But there were also surly dreams which one forgot completely, of which nothing remained but some mysterious aura, some obscure bemusement.13

The dream is the realm of unconscious or repressed desires. Anna’s avventura, when she flings herself out of her habitual life and into something alien and new, is like the affair Sandro then begins with Claudia, or like Fridolin’s urge to leave the country. It is that sense that real life is no longer real to you, that to live in the dream-world – a reality removed from this one – would somehow be more real.

Ophüls’ famously mobile camera conjures this feeling beautifully in Madame de…, in the waltz-montage that shows Louise falling in love with Baron Donati: tracking shots, punctuated by dance-themed paintings and sculptures, seem to spiral into each other, deeper and deeper into a way of life that is removed from reality but in which long-dormant needs can at last be fulfilled.

Huge mirrors cover the walls of the ballroom, reflecting the other dancers but making them seem to inhabit an alternate dimension, on the other side of the glass.

On the one hand, Kate McQuiston argues,

Ophüls privileges the waltz among musical genres; it is perfect accompaniment for his circular images and turning camera and for symbolizing the closed and ineluctable paths his characters must take. The very premise and eponymous central motif of Ophüls’s La Ronde is exemplary. The characters cannot quit their compulsive, seemingly mindless coupling and recoupling throughout the story, as dictated by the merry-go round and its waltz.14

But on the other hand,

Waltzing provides an opportunity for Ophüls’s characters to escape the constraints of the social situations that prohibit their love and creates a temporary postponement of their separation or demise. […] The exclusivity of the waltz is what makes the affair between Louise and Baron Donati […] possible in the first place.15

I would lean more towards the latter point of view: I think there is more of an emphasis on escape than on entrapment in Ophüls’ waltzes. In La ronde, for instance, the compère explains that most people – the characters in this film, for instance – do not understand reality because they see only a small part of it, whereas he sees everything en rond, in the round. He explains to the chambermaid that she is about to lose her job, but then he transports her two months into the future, to her next amorous encounter.

The material constraints of life fall by the wayside of the merry-go-round, a metaphor that evokes unconstrained though transient joy.

At several moments, the compère acknowledges the artifice of the film we are watching, liberating us from the seemingly compulsive narrative by showing how it is put together, reminding us that it is a story we are being told.

In Eyes Wide Shut, as Alice dances with Sandor, the ballroom around them seems hazy and unreal.

The roaming Steadicam and ubiquitous Christmas lights (multiplied by reflective surfaces) turn ordinary spaces into wonderlands where our peripheral vision is pervaded by strange, blurry colours.

The hints of existential angst in La ronde and Madame de… are expanded on in Kubrick’s film, where a frustration with decorum and habit turns into a conflict with reality itself, and where the need crying out for fulfilment is not exactly the need to be loved (as in Louise’s case), but something harder to define that expresses itself in an urge towards universal promiscuity. Fridolin in Dream Story realises that he is conflating his wife with all the other women he encounters:

[He] felt as though he were obliged to conquer her as well, as though she could not, should not be his again until he had betrayed her with all the others he had met that night.16

His and Albertine’s fantasies are, in a way, similar to Giuliana’s longing to have everyone she has ever loved around her like a wall, though their contexts seem very different. The overtones of betrayal and revenge in Dream Story and Eyes Wide Shut mark these as stories that are specifically about the desire to cheat on one’s spouse, but this desire is just the uppermost layer of a more complex urge. These characters are reacting not only to a (conceptual) marital betrayal, but to a discovery that disturbs their relation to friends, strangers, and the world itself.

Eyes Wide Shut, unlike Dream Story, ends with an affirmation of need:

ALICE: I do love you. And you know, there is something very important we need to do as soon as possible.

BILL: What’s that?

ALICE: Fuck.

Coming as it does at the conclusion of such a long, strange, and challenging film, this final line constitutes a wry joke at the expense of Eyes Wide Shut’s apparent self-importance. Perhaps all this drama could have been avoided if Bill and Alice had simply taken the trouble to maintain a more regular sex life. But there is a lingering uncertainty as to whether this is really the urgent need this couple should attend to. As McQuiston says:

The dualities of the film persist through the final word, ‘Fuck,’ […] which describes sexual union for the couple but is at the same time a shrugging dismissal of the unresolved issues that trouble their world. Like a waltz, the sexual act is repetitive and compulsive, and maintains what Kubrick shows to be a bifurcated, repressive, and even deadly status quo.17

Ophüls’ films and Eyes Wide Shut explore the idea that the respectable world in which these characters live militates against their happiness because, among other things, that world is confused and repressed about sex. However, sexual repression is associated with a more wide-ranging dysfunction in how this world’s inhabitants relate to each other. In Madame de…, Louise and the General are shown glumly retreating to separate beds in separate rooms, whereas Louise and Baron Donati embrace each other (on the dancefloor or in the back of a carriage) with overt, irresistible desire.

But the problem is not simply the absence of carnal pleasure in Louise’s life. She loves Donati because he represents a more radical escape from a more deeply rooted problem, visible not only in the alienation between the two marital beds but in every aspect of how these people live.

Eyes Wide Shut, set in the present but faithful to its early-1900s-set source text, takes an Antonioni-esque view of human progress. We appear to have made advances and to have become more frank about sexuality, but in many ways we are still living in accord with centuries-old assumptions, prone to spasmodic, destructive impulses, and drawn to transgressive encounters without knowing why they excite us (or being able to follow through with any of them). Alice’s prescription in the final line is incisive but tinged with irony. Sex is inextricably tied up with all the ‘unresolved issues that trouble their world,’ to use McQuiston’s phrase, but an orgasm will not resolve those issues. ‘To fuck’ has been an option all through the film, and one that husband and wife have been pursuing (in dreams or in reality), but there are reasons for the constant deferral of the act itself. Those reasons constitute the basis of the entire film; once they are dismissed, the film abruptly ends. The couple seem to face each other with eyes wide open; then we cut to black, and the eyes close.

Ophüls frames adultery as a fleeting liberation from repressive structures that tend to reassert themselves by the end of the film. The reckless moment (to invoke the title of my favourite Ophüls film) is also the only truly meaningful one in the protagonist’s life, a dream-like glimpse of fulfilment that vanishes all too quickly. In Eyes Wide Shut, there is no such glimpse of fulfilment. Alice’s dance with Sandor is not a waltz, and her dance partner is no Baron Donati – he is strange and creepy. The drift into other dimensions is revelatory but not liberating. It is a glimpse of something that makes ‘reality’ seem nonsensical, not of a better reality the characters could build together if they wanted to. In Red Desert, we follow a protagonist who is somewhat like Louise in Madame de…, having awakened to the coldness of her surroundings and the intensity of her emotional needs, but her journey through the film is more like the husband’s in Eyes Wide Shut. Fleeing from her home and seeking to understand why she feels alienated from it, Giuliana drifts through a series of disturbing but oddly inconsequential encounters. ‘Why do I need other people?’ she asks. The ‘why’ is also a ‘what’: what is it that Giuliana needs from people, or from that people-wall she imagines forming around her? Corrado is like a nightmare amalgam of Donati, Sandor, and Alice, a handsome but hollow would-be lover who dismisses Giuliana’s anxieties by telling her that all she needs is a good fuck. He is unwilling to engage with the fact that her (and his) world is more broken than that, and as a result his imposed solution will only inflict more damage.

Next: Part 38, Giuliana and her environment.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Pavese, Cesare, Among Women Only (1949), trans. D. D. Paige (London: Peter Owen, 1953), p. 19

Pavese, Cesare, Among Women Only (1949), trans. D. D. Paige (London: Peter Owen, 1953), p. 106. Italian text from Pavese, Cesare, Tra donne sole (Torino: Einaudi, 1998), p. 104.

Pavese, Cesare, Among Women Only (1949), trans. D. D. Paige (London: Peter Owen, 1953), p. 133. Italian text from Pavese, Cesare, Tra donne sole (Torino: Einaudi, 1998), p. 132.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 491.

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 88

Zanni, Adriano, Sequenze di fabbrica (Boring Machines, 2024). Book and music available via Bandcamp.

Cassani, Alberto Giorgio, ‘Uno sguardo al nuovo libro di Adriano Zanni, tra documenti di civiltà e barbarie’, Ravenna e Dintorni (26 May, 2025)

These images can be found in Zanni, Adriano, Sequenze di fabbrica (Boring Machines, 2024), pp. 50-53. The digital versions reproduced here were posted by Boring Machines on BlueSky (07 September 2025).

Schnitzler, Arthur, Dream Story (1926), trans. J.M.Q. Davies (London: Penguin Books, 1999), pp. 41, 88

Schnitzler, Arthur, Dream Story (1926), trans. J.M.Q. Davies (London: Penguin Books, 1999), pp. 34, 69

Schnitzler, Arthur, Dream Story (1926), trans. J.M.Q. Davies (London: Penguin Books, 1999), p. 76

Schnitzler, Arthur, Dream Story (1926), trans. J.M.Q. Davies (London: Penguin Books, 1999), p. 89

Schnitzler, Arthur, Dream Story (1926), trans. J.M.Q. Davies (London: Penguin Books, 1999), p. 92

McQuiston, Kate, We’ll Meet Again: Musical Design in the Films of Stanley Kubrick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 186

McQuiston, Kate, We’ll Meet Again: Musical Design in the Films of Stanley Kubrick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 186-187

Schnitzler, Arthur, Dream Story (1926), trans. J.M.Q. Davies (London: Penguin Books, 1999), p. 69

McQuiston, Kate, We’ll Meet Again: Musical Design in the Films of Stanley Kubrick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 199