Everything That Happens in Red Desert (23)

Valerio and the chemistry set

After Giuliana’s ambiguous suicide attempt and the confrontation at the end of the pier, Red Desert transitions into a seemingly tranquil domestic scene. Giuliana and Ugo are back at home, playing with their son. Ugo is about to leave on a week-long trip and Giuliana is packing his suitcase. The fallout from the previous scene pervades this one: beneath the amicable surface we can feel a tension between the couple, we can sense that Valerio picks up on this, and overall we can see the gulf widening between Giuliana and her family.

At the end of the daytrip sequence, there is a desolate long shot of the four characters standing by the car, surrounded by fog.

The moment is deeply uncomfortable: all four characters are upset and embarrassed, in different ways and for different reasons, and the situation cannot be resolved quickly or easily. All four people will have to get back in the car. One of them will have to drive in reverse very carefully from the edge of the pier, then even more carefully accomplish a three-point turn, in order to drive back to where Max and Mili are waiting (picking up Giuliana’s purse on the way), all while still feeling anxious about the quarantined ship nearby. The group will then have to part on friendly terms and go their separate ways.

This is a nightmare of social awkwardness, caused by the eruption of extreme, inexpressible emotions in a context where practical issues need to be resolved. To Ugo, Giuliana’s behaviour seems nonsensical: she was so scared of the ship, and yet she has driven back towards it; she feared death, and yet she has almost killed herself. He is unable or unwilling to see that she is afraid of something worse than a mere infectious disease or death by drowning, and that both these escape attempts – from the diseased ship and from the fog – were born of the same impulse.

Now we cut to a scene in which Ugo, not Giuliana, is escaping. She asks how long he will be away, and his answer – ‘five or six days’ – is vague enough to suggest that this trip has been arranged on the spur of the moment. Faced with issues he cannot understand, Ugo retreats into his work, which is focused on scientific problems that can be identified and solved, like the over-heating burners he dealt with in his first scene.

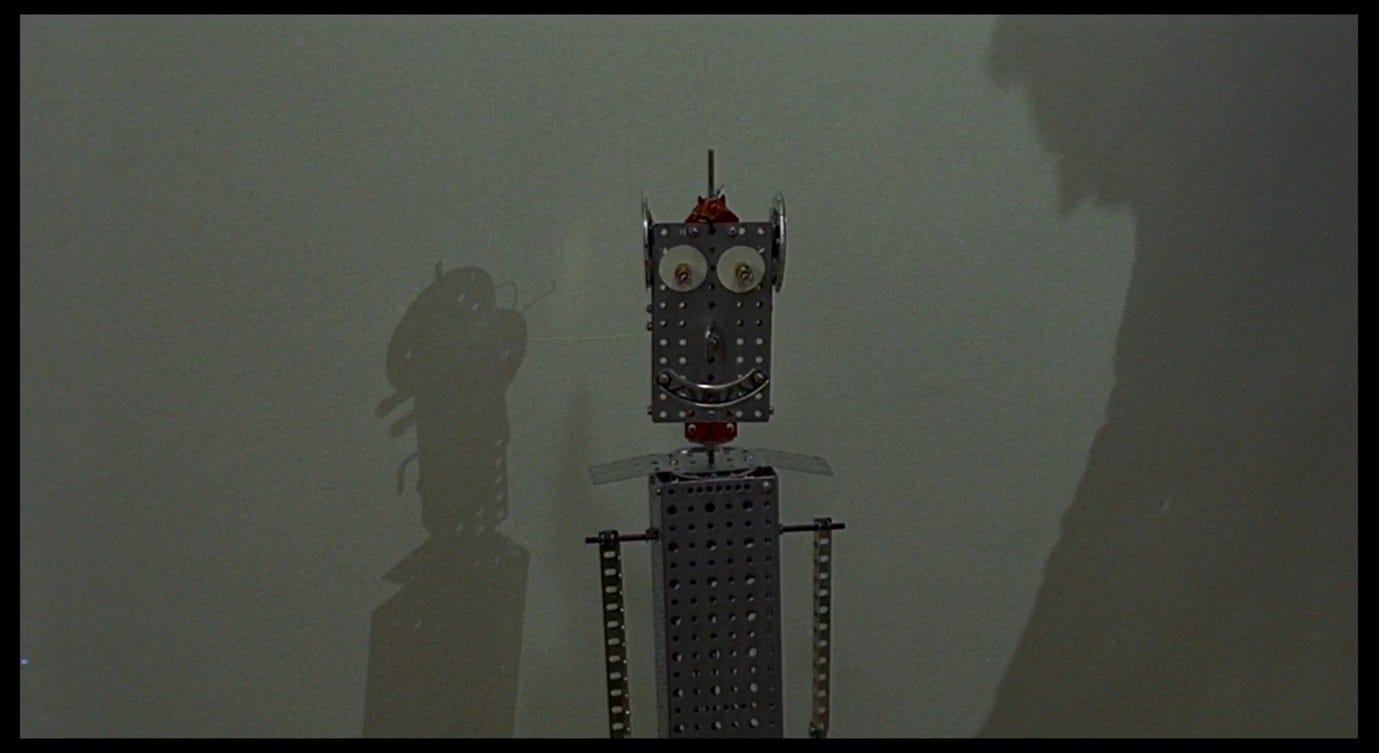

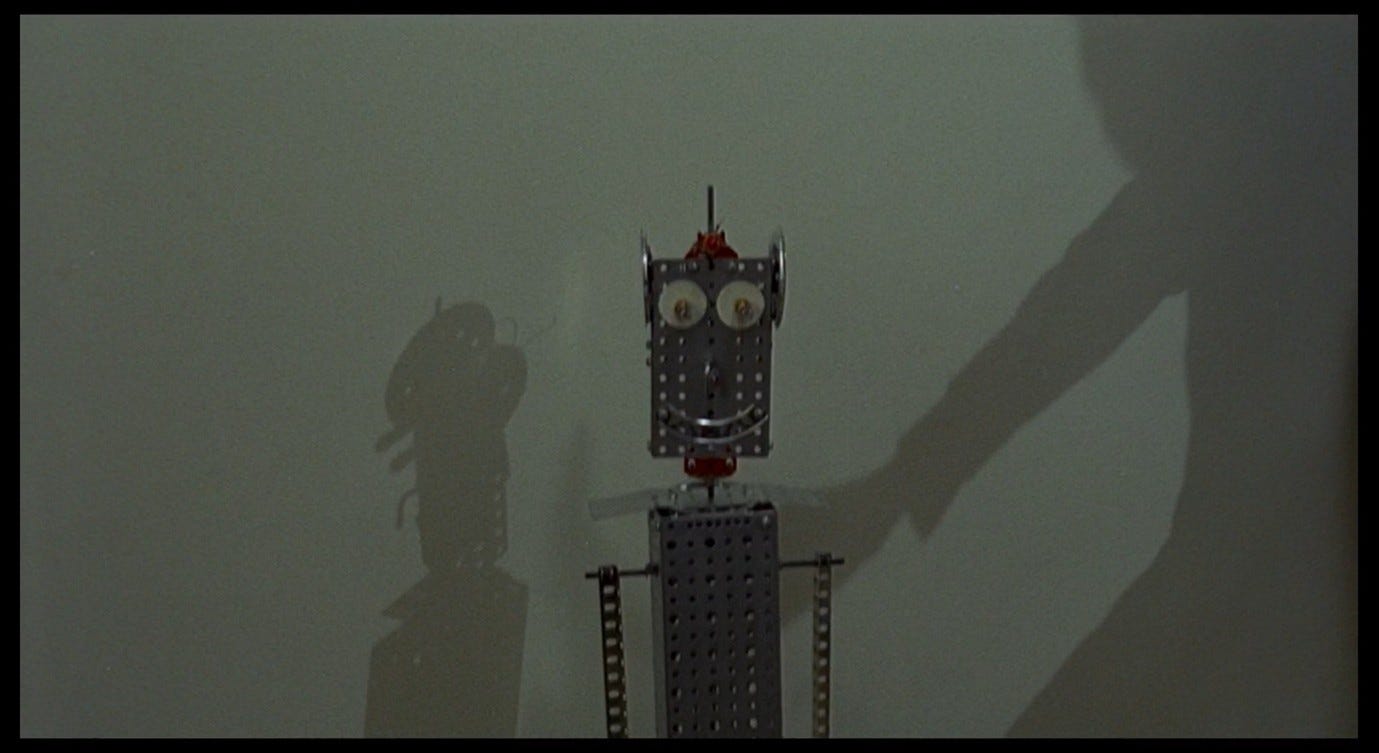

The first shot of this sequence underlines the theme of a ‘retreat into science.’ Valerio’s robot is immediately positioned at the centre of the frame, casting its shadow against the clear white wall of the apartment, with Ugo’s shadow to the right.

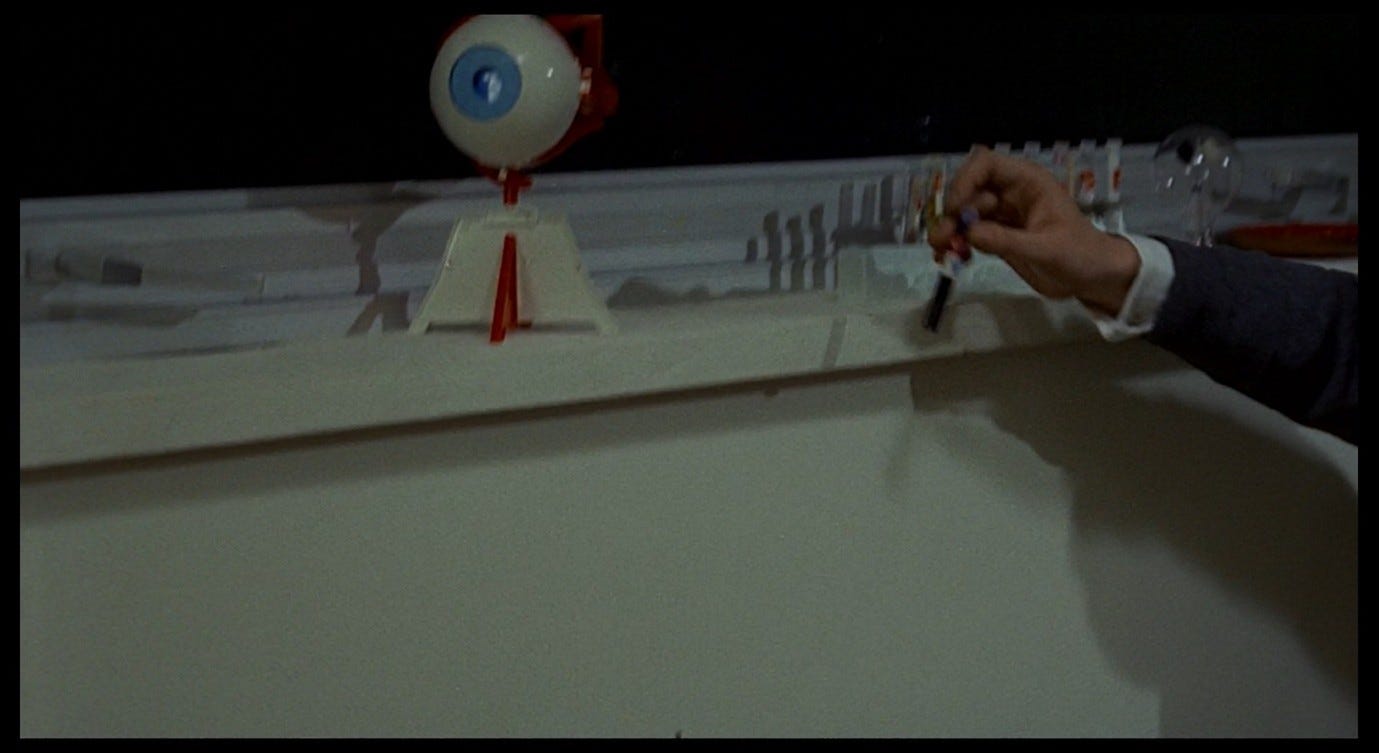

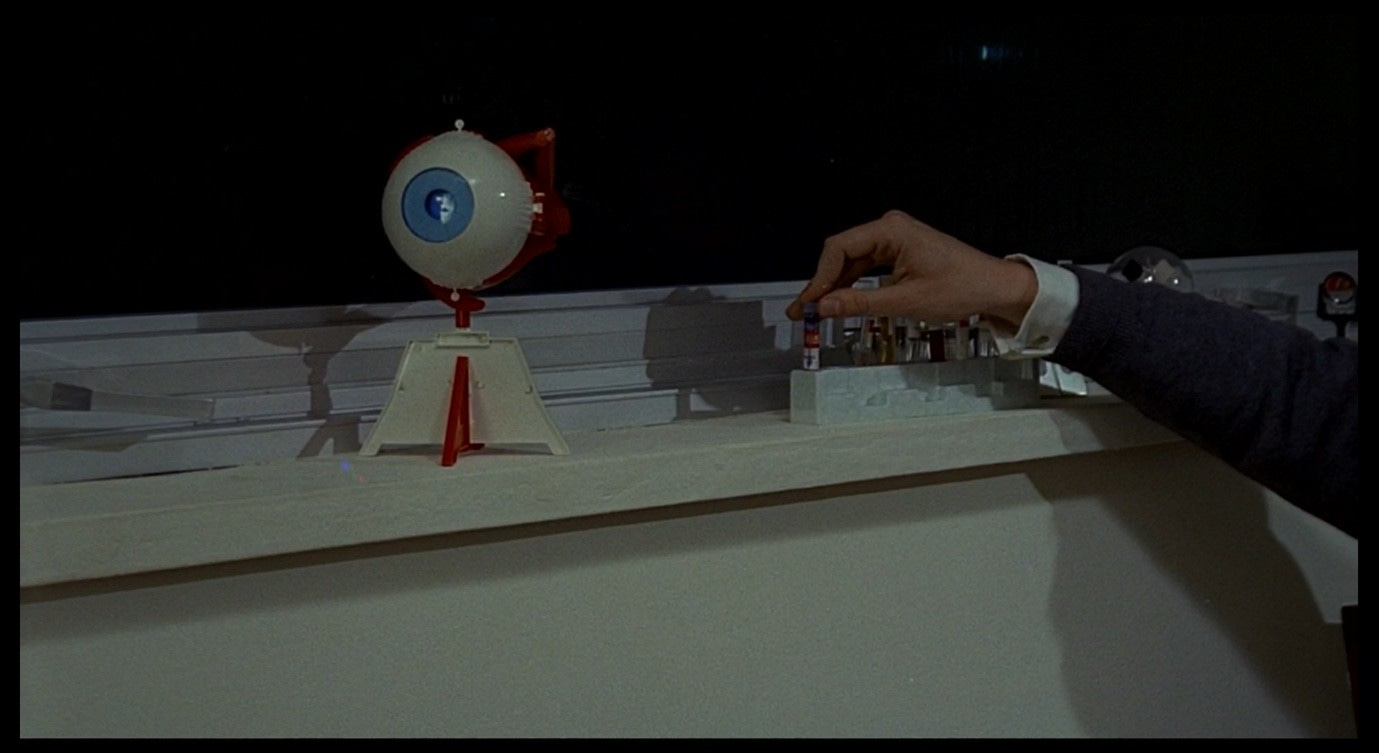

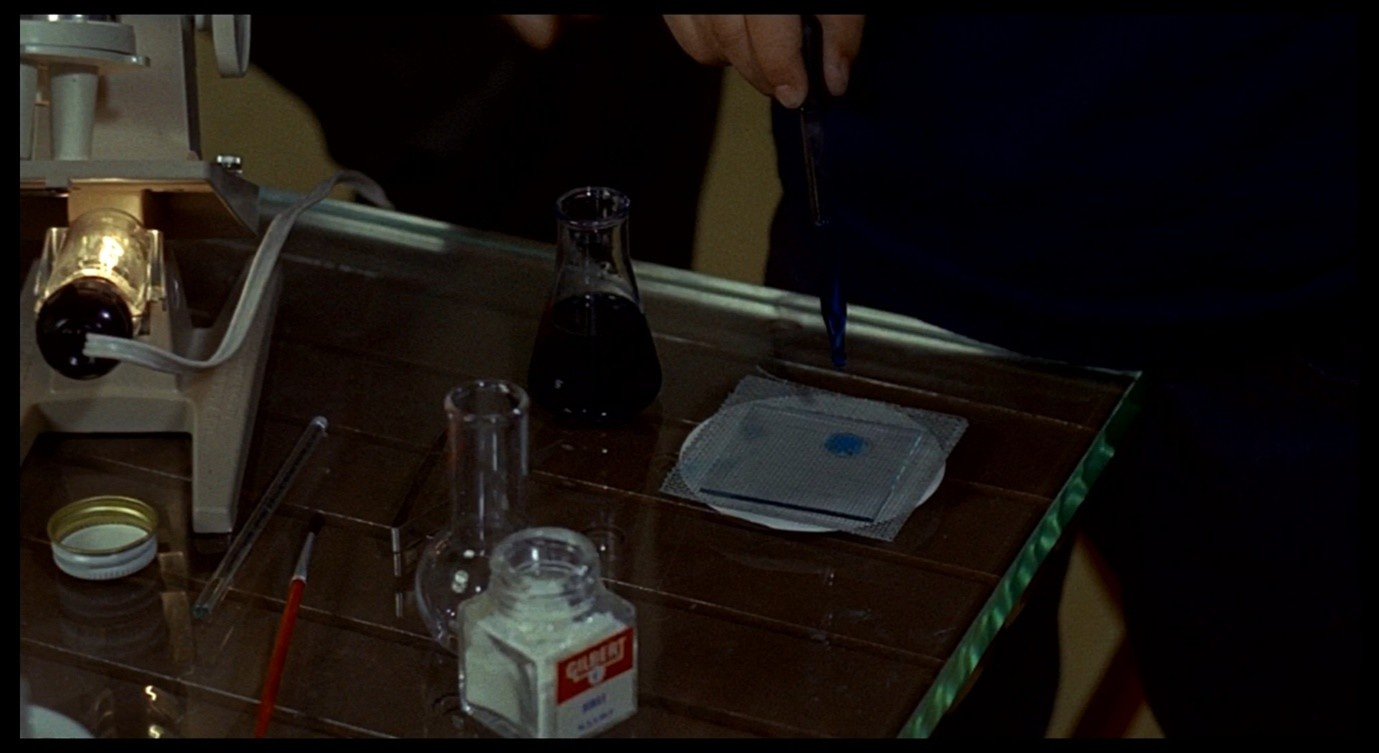

As Ugo’s hand enters the frame, the camera rises with it and watches it place a test-tube in a rack. The precise, mechanical eye of the camera sees its counterpart on the window-sill, a large plastic model of an eyeball mounted on a stand.

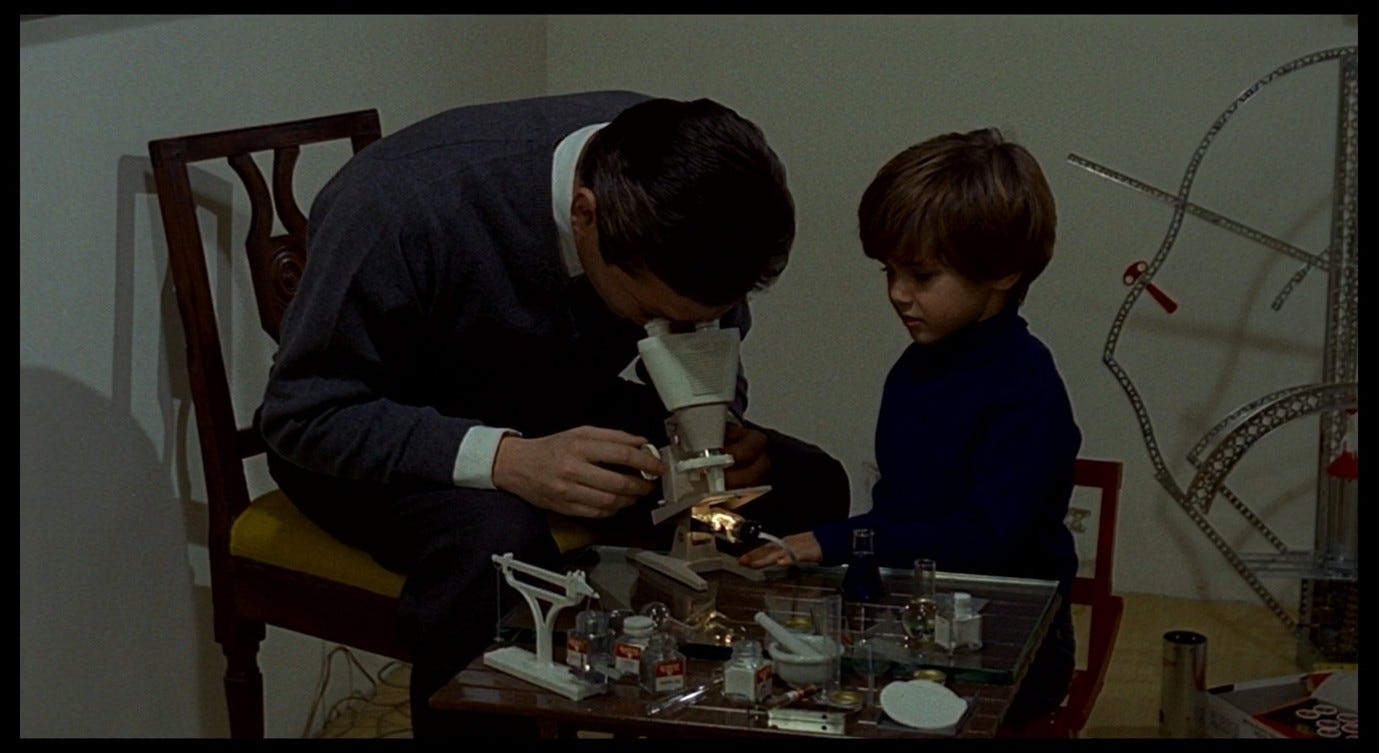

Then the camera-eye pans right to see Ugo examining a chemical mixture through a microscope (that is, a pair of mechanical eyes). ‘Ooh, how beautiful [che bello],’ he says, firmly back in his comfort zone.

Near the start of the film, in the ‘night terrors’ sequence, we saw the robot acting as a sentry in Valerio’s room, tirelessly marching up and down to guard him from danger while he slept. Giuliana switched the robot off – surely Valerio did not need it, he had his mother checking in on him – but its eyes continued to glow watchfully after she left.

Now we see it again, still keeping vigil in the little boy’s room, an emblem of cold, mechanical reason that feels like a corrective to the flailing mess of torment that Giuliana has become. When she had a nightmare, there was the robot doing its duty. Now, after her waking nightmare in the fog, the robot steps in again to maintain order. It moves autonomously, it sees in the dark, and it casts a long shadow in this home – and its shadow is visually equated with that of Ugo, because this is really his home more than Giuliana’s.

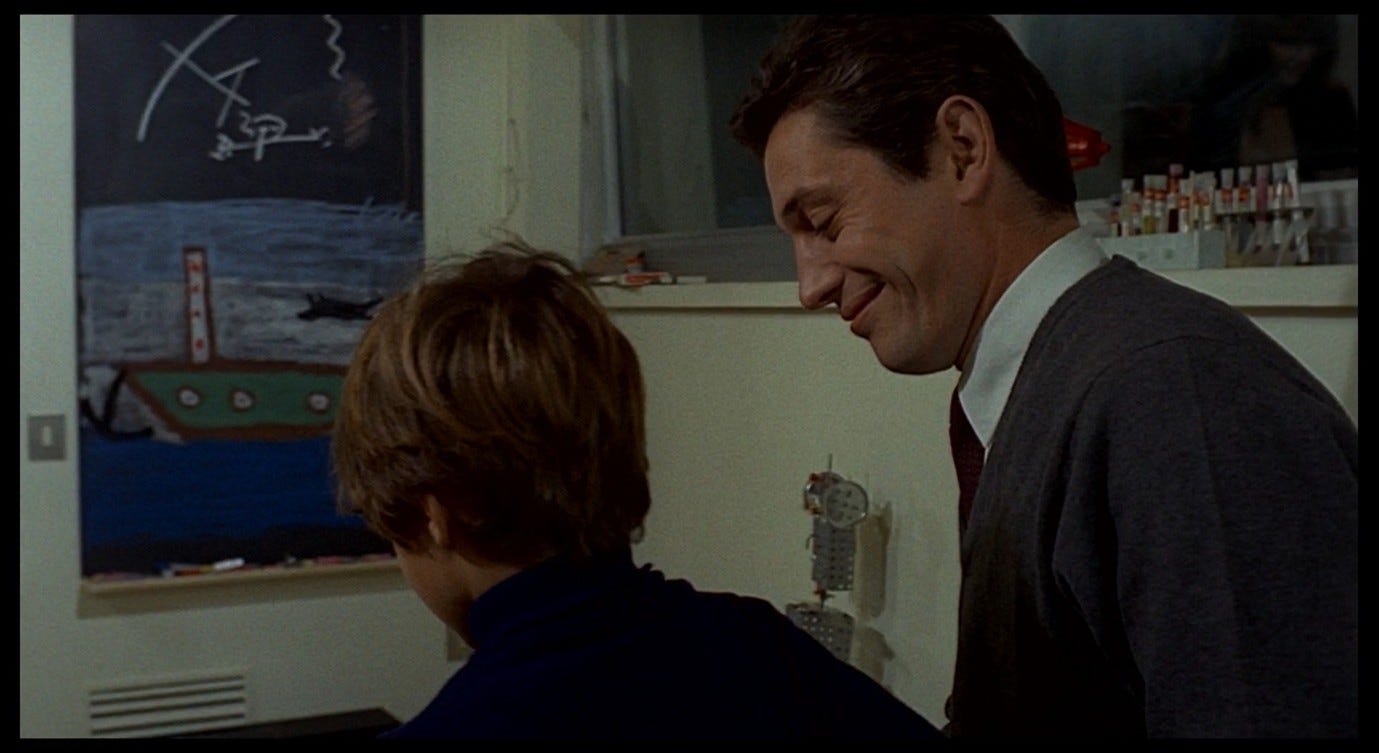

Ugo is engaged in an experiment, combining two liquids from test-tubes to see how they interact. It is an experiment in relationships, where one substance can be mixed with another to create a predictable result. When you look through the microscope at this result, you do not feel surprise: you remark upon the beauty of the chemical reaction (‘Ooh, che bello!’), which is presumably ‘beautiful’ for definable, scientific reasons. In this case, the experiment is for Valerio’s benefit – either Ugo is showing it to him or he is showing it to Ugo, perhaps following instructions from a chemistry set – and when Ugo remarks on the beauty of the chemical reaction, he is both modelling the correct response (so his son can emulate it) and complimenting Valerio’s work (for the sake of positive reinforcement). Ugo leans back from the microscope, allowing Valerio to follow his lead by looking through the eye-piece.

The shot has moved from the robot to Ugo to Valerio, locating Ugo at the centre (and in control) of the environment in which his son is developing.

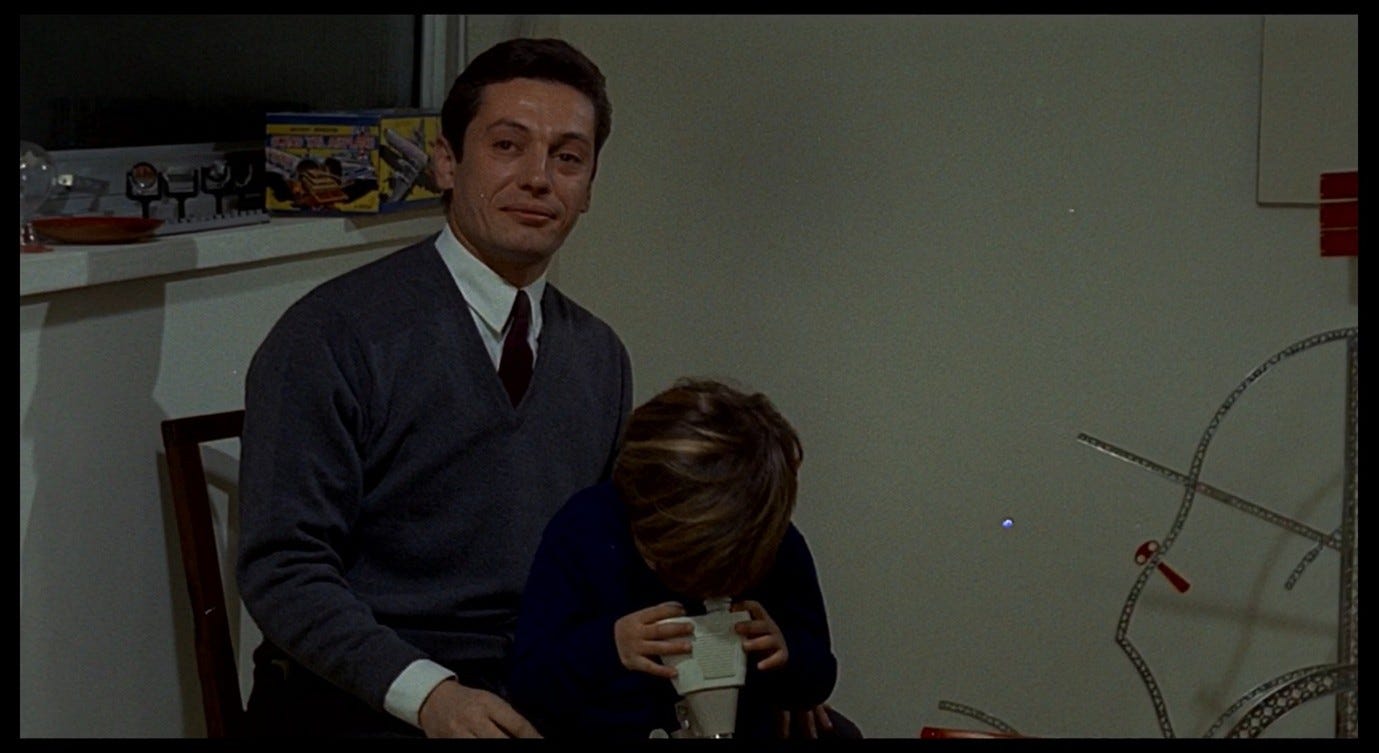

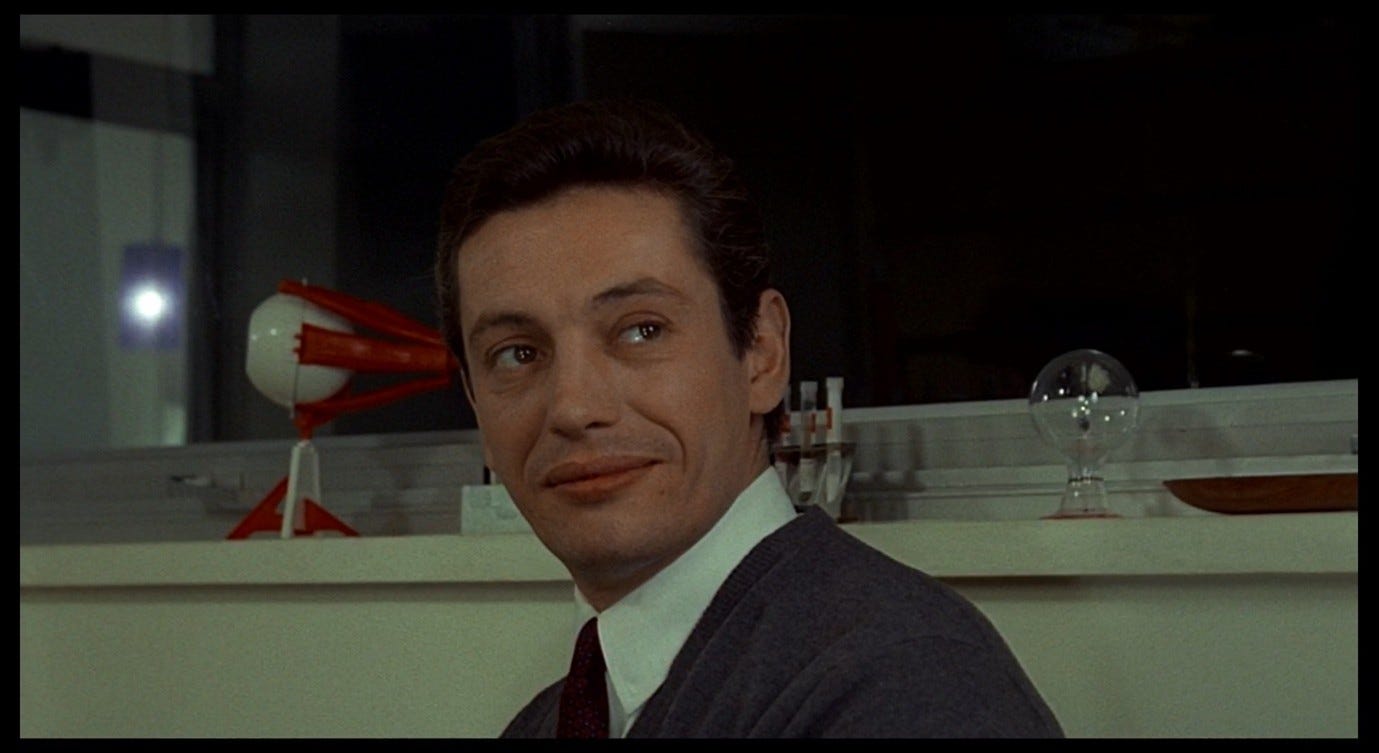

We hear footsteps approaching, and Ugo looks up just before Giuliana speaks. In this momentary pause, we have time to register a change in Ugo’s expression. The complacent smile elicited by the chemistry set now breaks down very slightly, the facial muscles relaxing as the head rises.

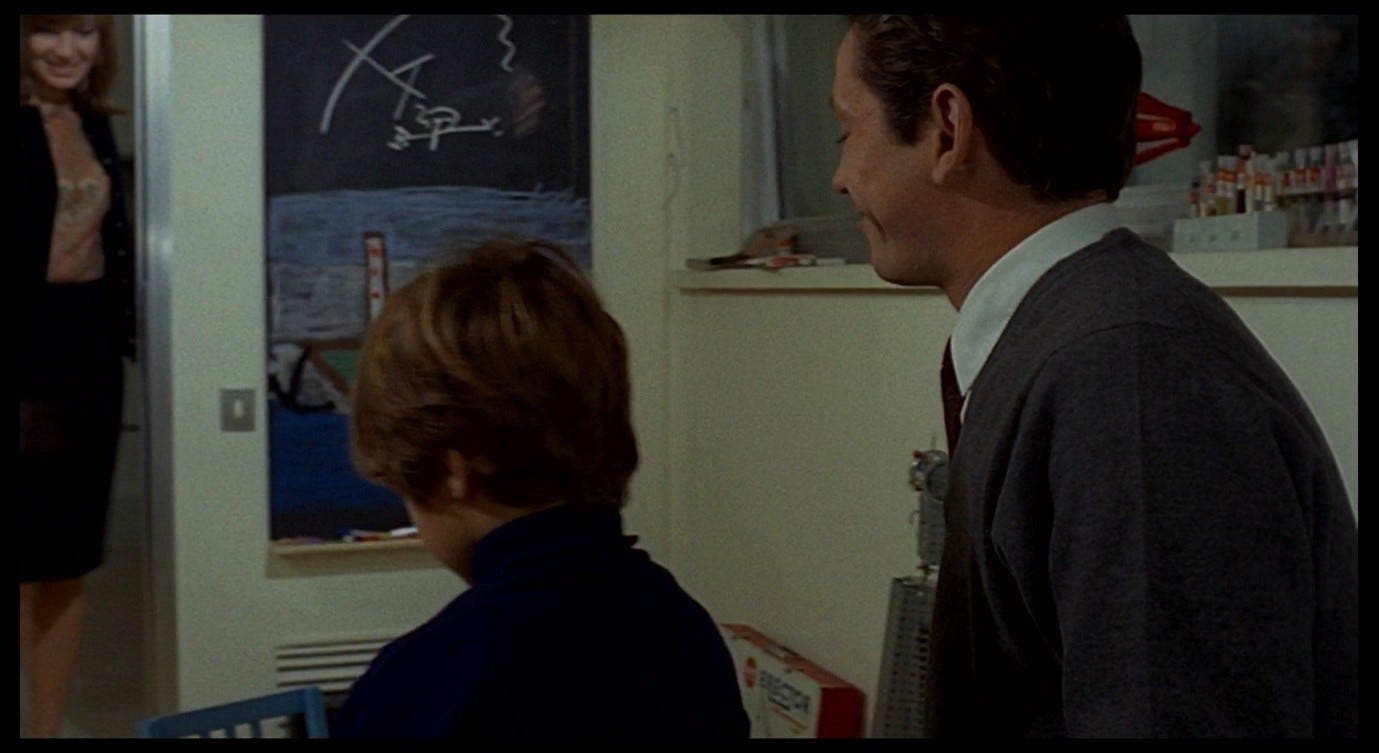

Ugo does not scowl at Giuliana, but neither is he happy to see her. His face contains the lingering sourness of the (possibly silent) argument that must have passed between them after the previous scene. Ugo also seems protective of Valerio and of the father/son bonding that is taking place: he does not invite Giuliana to share in this moment. If anything, he seems worried that she might intrude upon it. In the next shot, Giuliana hesitates in the doorway, slightly less in-focus than Valerio and Ugo in the foreground, scrutinised by Ugo and by the plastic eye that shares his eye-line, its garish red extra-ocular muscles ‘directing the eye’ towards Giuliana.

We cannot see the robot now, but we know it is down there, watching her too. All these eyes on Giuliana are guarding Valerio, who is safely absorbed in looking through the microscope.

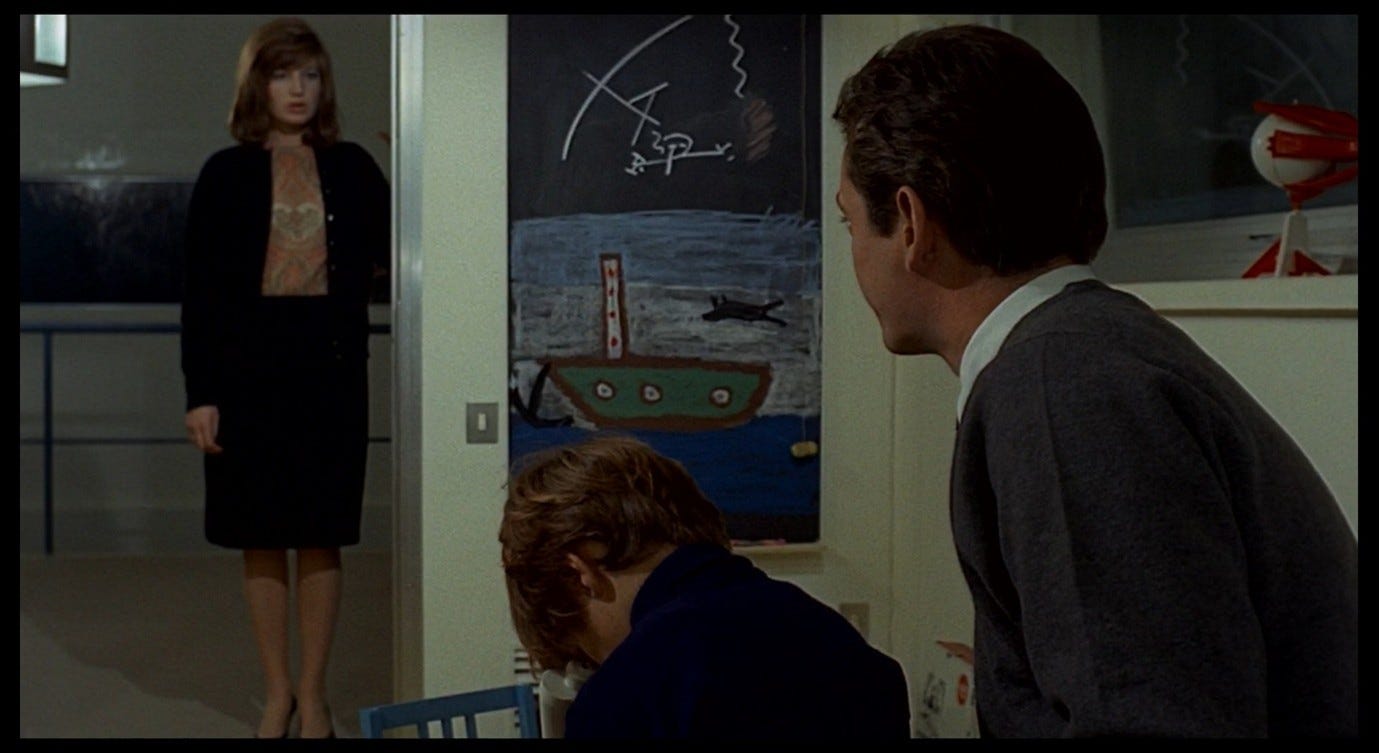

Paired with Valerio at the centre of the frame, between Giuliana and Ugo, is a blackboard on which Valerio (presumably) has drawn a ship against a background of black sky, grey fog, and blue sea.

The ship’s anchor hovers above the blue. Is it meant to be on the sea-bed, and is this a childish mistake? Or is Valerio picturing the moment before the anchor breaks the surface of the water? Or does the grey represent the sea and the blue the sea-bed, and has the ship sunk? The latter interpretation would explain the strange black creature that floats nearby, like an upside-down lizard, unless this is supposed to represent a bird or a cloud. A small yellow object, drawn against the blue, could be a floating buoy or an object stuck in the sea-bed. In the upper portion of the board, there are two geometrical diagrams and a squiggly line that transitions into a pinkish smudge.

This striking image, or set of images, reminds us of Valerio’s paintings in his parents’ bedroom: hard to make sense of, a little disturbing, comparable to the abstract modern art seen elsewhere in the apartment and in Ugo’s factory, and clearly influenced by the industrial setting in which Valerio lives.

The chalk drawing on the blackboard plays with distinctions between air, earth, and water, between animate and inanimate objects, between figurative and abstract art, and between pictorial art and scientific diagrams. It adds to our impression that Valerio is comfortable with the world he lives in and with this world’s blurring of states and boundaries. Despite its ambiguity, the keynote of the drawing is stability. Wherever the anchor is supposed to be, the ship seems stable. The diagram suspended above it (probably drawn by Ugo to illustrate a lesson) suggests an orderly scientific mindset.

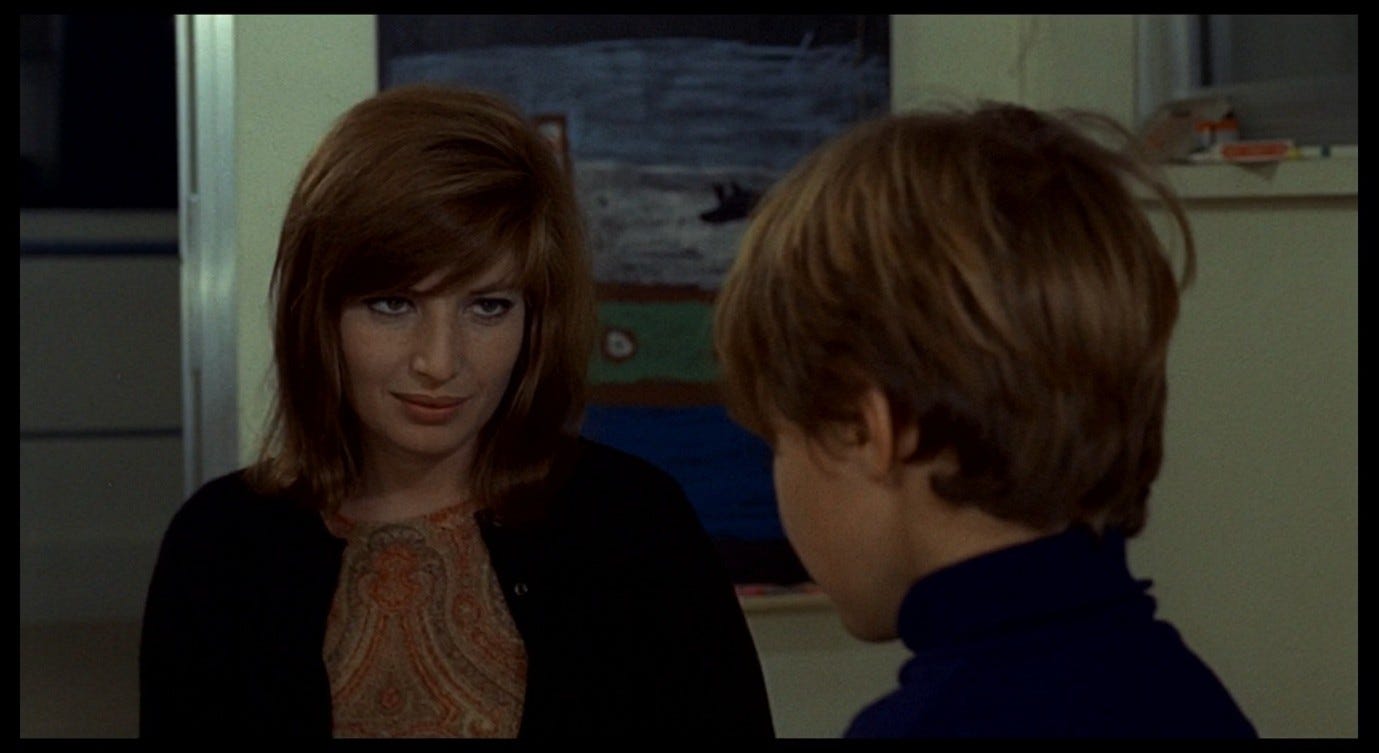

On all sides, Valerio’s bedroom works to exclude Giuliana, so she hovers nervously on the threshold. As she starts to leave (to resume packing Ugo’s suitcase), Valerio looks up and calls her back. Giuliana smiles happily as she enters the room to see her son’s trick.

‘What is one plus one?’ he asks. ‘What a question,’ she says. ‘Two, no?’ As Giuliana comes closer, the camera tracks and pans to keep her excluded and focus on Valerio, with Ugo beside him smiling proudly.

In the next shot the camera is positioned on Giuliana’s side of the table: we see Valerio releasing two drops onto the slide, carefully hitting the same spot both times.

‘One...one two [Una…una due],’ he says, then holds the slide up for his mother’s inspection and demands, ‘How many?’

His face as he says this is provoking, stern, almost angry. He is confronting her with her mistake: ‘If one plus one is two, what do you call this?’ Her smile has fallen somewhat. ‘One, it’s true,’ she says. ‘Will you look at that [Ma guarda un po’].’ Her eyes follow the slide as Valerio puts it down, then she looks at him. He does not meet her gaze.

So far, in this scene, we have picked up on the tension between Giuliana and Ugo, and on the sense that he is protecting Valerio from her influence. When the boy calls his mother into the room, for a moment he seems to be trying to dispel the tension, to bring his mother back into the fold. She is clearly delighted that he wants her and she happily plays along with whatever this game is. But the game turns out to be a trick at her expense, and Valerio plays it without any sense of playfulness, but rather with an air of vindictive cruelty. He taunts his mother with the amorphousness of reality, with the phenomenon of entities blurring into each other, which is a recurring motif in her experience of the world. It is like showing her a picture of two people and then blurring it to make them appear as one. This is the effect of the dissolving fog that pervades Giuliana’s world. She has a tendency to relate to the world as an indistinguishable mass of things, to love ‘husband-son-job-dog,’ rather than doing as the doctors have prescribed and relating to things as discrete, separate objects.

An alternate version of this scene might have had Valerio demonstrating ‘separation’ rather than ‘assimilation’: he might have mixed two different substances and shown them refusing to mix with each other. Such a demonstration would have felt more instructive, a lesson to Giuliana in how the world really works and in how she needs to engage with it if she is to make her gears mesh. Instead, he shows her something which seems to mirror her own dysfunction. It mirrors her isolation too, by showing the ‘one’ attempting to connect with a ‘two,’ but still ending up alone. ‘[I]t is a terrible scene from Giuliana’s perspective,’ says Sam Rohdie; ‘it further dissolves her very tenuous grasp on herself and on the world, and separates her from a love and connection to her little son.’1 Rohdie’s phrasing evokes the sense that there is a ‘love and connection’ here, a version of Giuliana who enjoys such a connection, but that she (the other Giuliana) is separated from it.

In Tender is the Night (the book Anna takes on holiday in L’avventura, along with the Bible), Nicole Diver’s mental illness affects the way she sees and relates to the world, especially the way she sees and relates to her family. When she and her husband, Dick, are searching for their children in a fairground, Nicole seems reluctant to find them:

Evil-eyed, Nicole stood apart, denying the children, resenting them as part of a downright world she sought to make amorphous.2

As they drive away having found the children, she attempts to crash the car and kill all of them, as though to fulfil this urge towards dissolution. Earlier in the same passage, Dick is overcome with despair in the face of Nicole’s schizophrenic episode:

A wave of agony went over him. It was awful that such a fine tower should not be erected, only suspended, suspended from him. Up to a point that was right: men were for that, beam and idea, girder and logarithm; but somehow Dick and Nicole had become one and equal, not apposite and complementary; she was Dick too, the drought in the marrow of his bones. He could not watch her disintegrations without participating in them.3

In Dick’s mind, the married couple are supposed to be ‘complementary,’ two discrete beings that remain separate but related to each other, like two separately erected but inseparable towers (the ones we see at the beginning and end of Red Desert, for instance). The woman might depend upon the man’s mathematically precise structural integrity but she should not partake of it, nor should he partake of her weakness and dependency. In this case, though, Nicole is like a fine structure that dangles precariously from Dick and infects him with her un-groundedness, her ‘disintegrations.’ He is emasculated and rendered impotent as though by venereal disease (‘the drought in the marrow of his bones’), robbed of his proper, masculine, husbandly, fatherly role. ‘Fifteen minutes ago,’ he thinks to himself, ‘they had been a family. Now [...] he saw them all, child and man, as a perilous accident.’4

F. Scott Fitzgerald made use of experiences from his own marriage to Zelda Sayre in this novel, and was deeply resentful when she tried to do something similar:

Zelda’s novel – which would be published as Save Me The Waltz – proved to be deeply autobiographical and thus touched on material and situations that Fitzgerald planned to use in Tender is the Night. […] The Baltimore doctors were inclined to agree with the argument that Zelda’s experiences shared with her husband were ‘common property’ when it came to writing about them. But Fitzgerald refused to concede this point and insisted that there be significant changes to Zelda’s text before it could be considered for publication.5

Something about the refusal to see their life together as ‘common property’ resonates with Dick Diver’s anxieties about Nicole. Perhaps Fitzgerald was disturbed by the idea that ‘Scott and Zelda had become one and equal, that she was Scott too.’

In Red Desert, we experience this dynamic from the perspective of the recently institutionalised and perhaps soon-to-be-re-institutionalised wife. Giuliana’s illness will not be permitted to infect her husband or her son. There will be no disintegration or emasculation for Ugo, who is able (as Dick Diver was not) to focus on his work when Giuliana is sick, and who has trained his son to protect himself from his mother’s influence. With his ‘one plus one’ trick, Valerio is saying to his mother: ‘You are shut out from this family, and when you try to come back in, you will find yourself alone.’ Giuliana-plus-husband-and-son is still Giuliana-alone. Monica Vitti beautifully conveys her character’s quiet desolation in this moment. She is still smiling, outwardly calm, and duly impressed by her son’s cleverness. But the way she stares at the blob on the slide, as it is placed on the table, tells us that she sees something devastating in it; and worse, the look in her face as she stares at her son tells us how deeply he has hurt her. She looks at him with a kind of wonder. Is he being deliberately cruel? Or was this just a harmless joke that inadvertently triggered her?

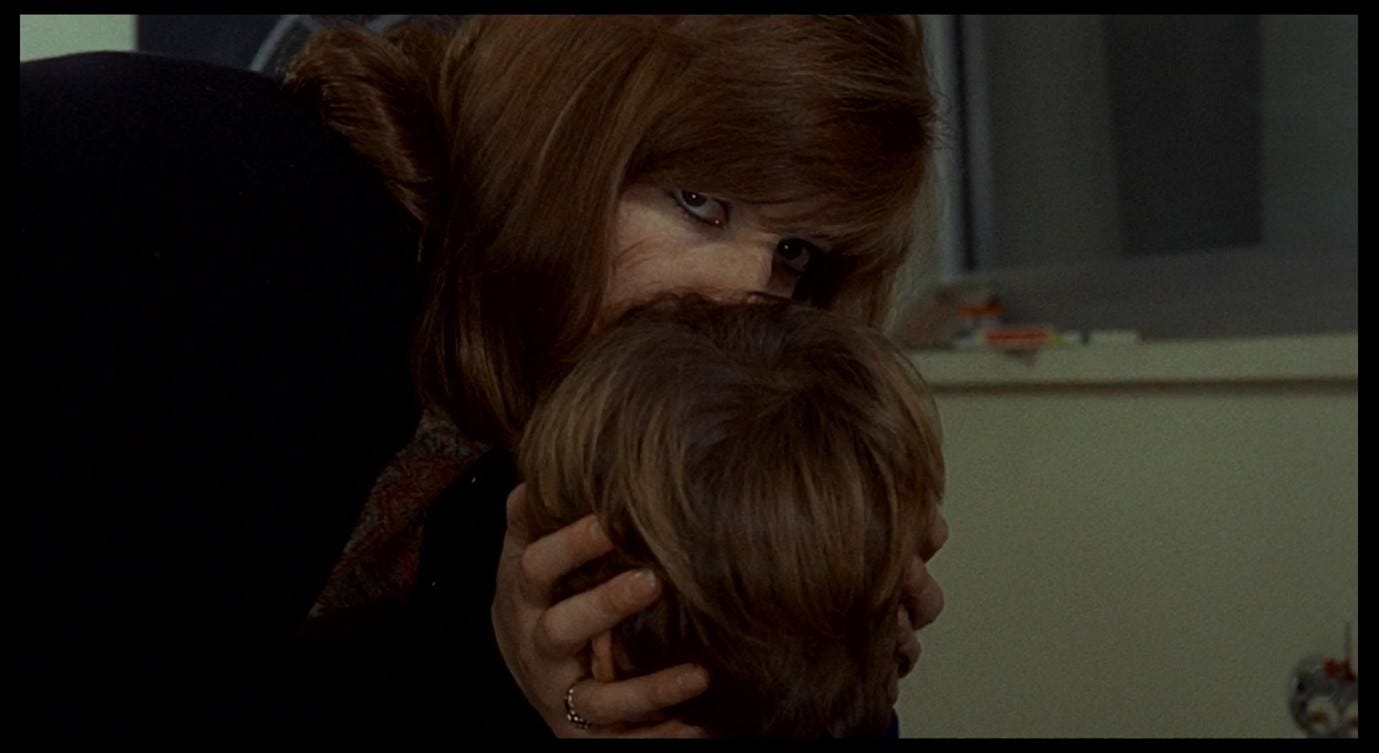

When Giuliana leans forward to kiss her son’s head, there is a desperate, feverish quality to the gesture, as if she were trying to force an emotional bond at the moment when she feels most alienated from the boy.

She completes the gesture by pausing with Valerio’s head in her hands and staring towards the camera.

For a moment we might think she is looking at Ugo, but as she gets up and walks away the camera pans to reveal that he was positioned to the right of the camera. We see his gaze follow her as she leaves. As at the beginning of the scene, his smile subsides almost imperceptibly, and his eyes are level with the plastic eye on the window-sill.

It is never revealed what Giuliana was looking at in this moment, and indeed the geography of this shot and the next is unclear. She seems to be looking towards the back of Valerio’s room but the next cut finds her in the master bedroom, taking Ugo’s clothes out of a cupboard.

This disorienting transition affects how we read Giuliana’s haunted stare: she was not looking at anything that could be empirically observed by the camera, but at something that only she could see, and something that in that moment was perhaps embodied by the camera itself. She is watched by the robot, the plastic eye, and Ugo, and her son’s trick makes her feel uncomfortably ‘seen’ by him as well. And there we are, watching the whole thing through the camera lens, coldly observing the torment she is trying to hold inside.

There is a similar moment in The Babadook, when Samuel performs a magic trick for his mother. He is nicer to his mother (in this moment) than Valerio is to Giuliana, but his sternness when he says ‘I haven’t finished!’ is reminiscent of Valerio’s confrontational ‘How many?’

When the trick is completed, Amelia embraces her son and says, ‘Happy Birthday, sweetheart.’ She cannot tell him she loves him, though – she never says this in the course of the film – and as she holds his head she looks away into the middle distance, then closes her eyes. The low, mournful growl of the Babadook can be heard on the soundtrack, mingling with the wind that blows through the trees. We can feel a tension and a distance between these two characters, quietly persisting in spite of their apparent closeness.

There are also echoes of the Giuliana/Valerio relationship in Laurent Cantet’s Time Out, when Vincent comes home to his family and embraces his children in the same manner: clutching their heads but staring past them or over them.

As in Red Desert and The Babadook, we are seeing a parent who has just experienced, or is in the midst of experiencing, a mental breakdown. In each case the parent looks into the child’s face but then has to look somewhere else, as if unable to bear a head-on confrontation with this relationship (or lack of relationship) in the wake of what has just happened. Vincent’s wife, like Ugo, looks on anxiously, trying to measure the possible damage this embrace might cause.

One day, Samuel will have to confront the Babadook himself. His magic tricks are his way of engaging with the uncomfortable truth that ‘life is not always as it seems,’ that there are invisible monsters in our brains, and that we may never be able to banish them. He gets angry with his mother because he needs her to engage with this truth as well. Vincent’s children – especially his eldest, Julien – are clearly affected by their father’s breakdown, and will have to come to terms with it as they grow up. Julien rages at his father for his perceived callousness towards the rest of the family, but as his father embraces him, Julien realises that the problem is deeper and more complex. Both Samuel and Julien end up seeing (at least partially) what their mentally ill parent sees, and we watch them struggling to process this revelation.

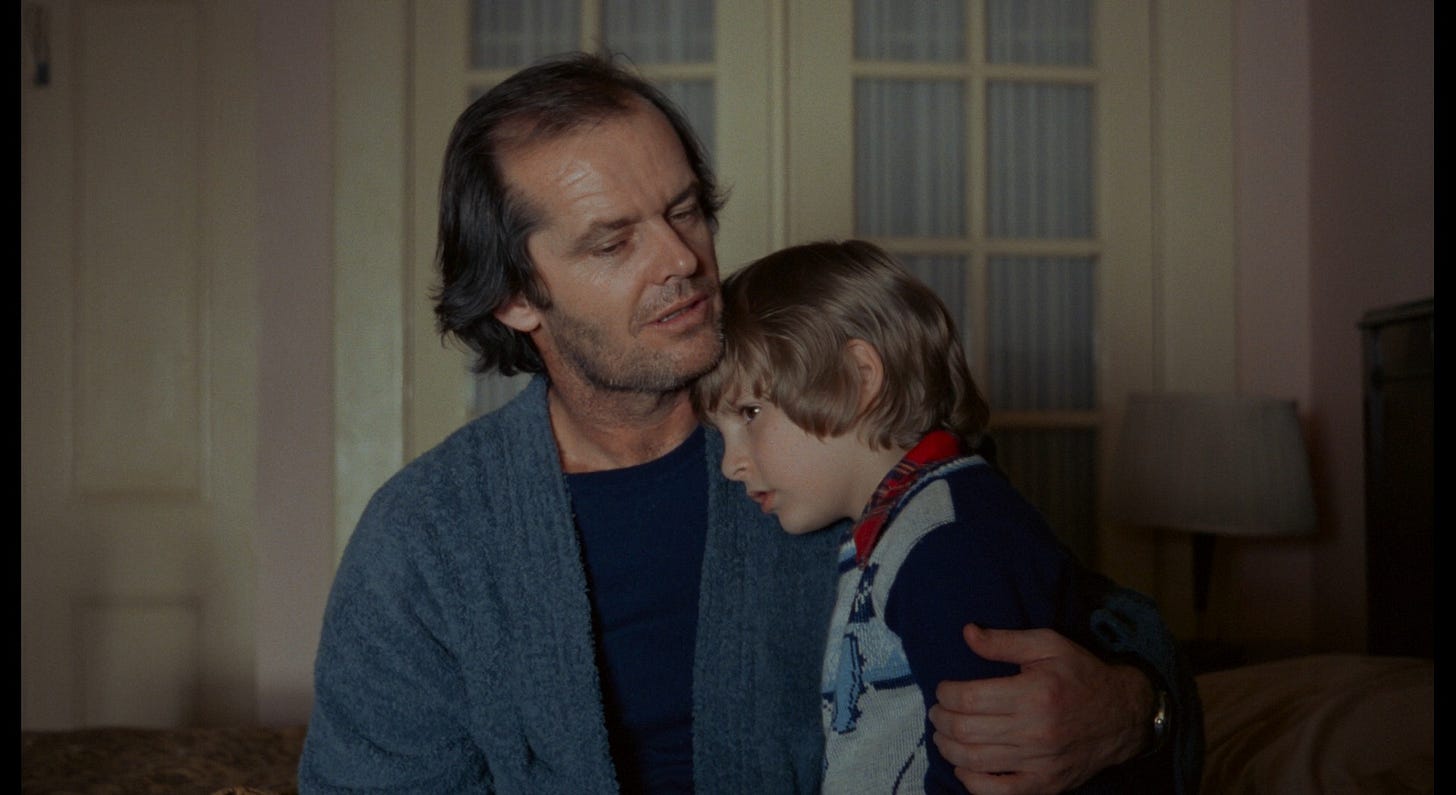

This motif – of the parent embracing the child but looking over their head – also occurs in Carrie and The Shining, at moments when the appearance of warmth and affection masks the imminent eruption of murderous violence.

It is easy to see why such a motif would be used so often in horror films. In real life, it does not necessarily feel unsettling to embrace someone without seeing their face, but when we watch a film we are constantly reading the characters’ faces to understand the relationships between them. It is disturbing to be deprived of a reaction-shot when we would normally expect one, but it can be even more disturbing to see a reaction shot that the other character cannot see. The camera has a special ability to re-frame an affectionate hug as a moment of profound alienation. Valerio, Samuel, Julien, Carrie, and Danny can only feel that they are being hugged, but the camera can look at the parent’s face and show us how they really feel.

Time Out revolves around this dynamic: the seemingly successful husband and father has in fact been unemployed for months, driving aimlessly for days at a time and conning his former colleagues out of their money. The shot of him embracing Julien but looking away from him, while explaining how hard he has worked to conceal the truth and maintain their way of life, dramatises in miniature what has been going on throughout the film. In Red Desert, Giuliana does not just look beyond her son, she looks into the camera: what is being ‘dramatised in miniature’ here is the crisis Giuliana discussed with Corrado, centred upon the difficulty of seeing and being seen. She cannot look at her son; she cannot avoid being seen by the camera; she cannot avoid seeing the camera looking at her; and she cannot avoid being seen by Ugo as well. It is not just that she is unwell and wishes no one could see her illness. The constant, inescapable sguardo – hers and other people’s – is part of that illness, and the medium of cinema is uniquely equipped to show this.

Compared to the films mentioned above, in Red Desert the other components of the family unit seem less vulnerable, more self-sufficient, to the point that they sometimes appear (from our Giuliana-centred point of view) callous or even cruel. Valerio’s games, unlike Samuel’s, are focused on the empirically observable world, on stable, intricate structures (like the Meccano sets along the far wall of his room), and on phenomena that can be examined under a microscope. Whatever Giuliana sees when she looks over Valerio’s head, she is the only one in the world to see it. Because she seems to be looking at us, or at least in our direction, we feel a chilling sense of contact with this unknown horror as well. We also feel that it has something to do with the act of looking or being looked at. It is something that Giuliana sees or something about how she sees; something that looks at her or something about how she is looked at.

Next: Part 24, The suitcase and the gyroscope.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 116

Fitzgerald, F. Scott, Tender is the Night (1934 edition), ed. Arnold Goldman (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 270

Fitzgerald, F. Scott, Tender is the Night (1934 edition), ed. Arnold Goldman (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 270

Fitzgerald, F. Scott, Tender is the Night (1934 edition), ed. Arnold Goldman (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 269

Hook, Andrew, F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Literary Life (Gordonsville: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), p. 105