Everything That Happens in Red Desert (28)

Shifting focus

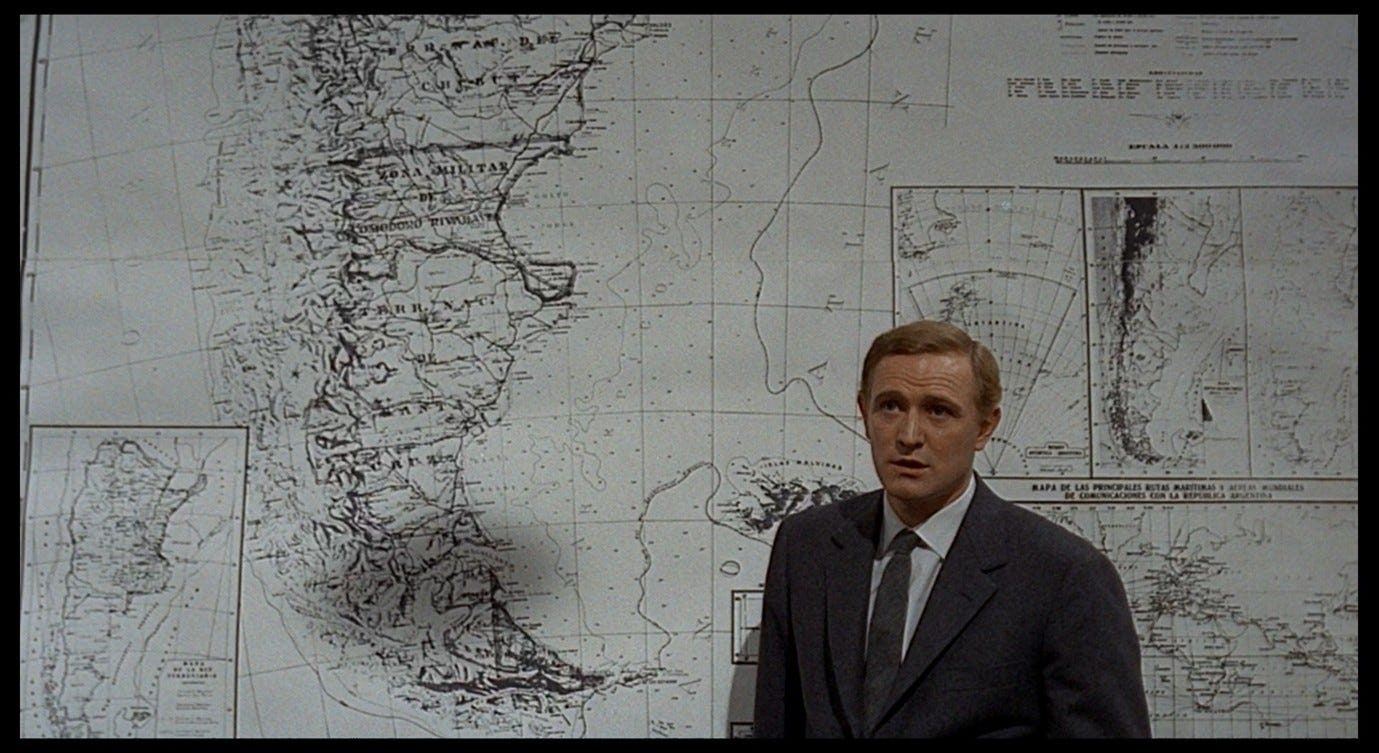

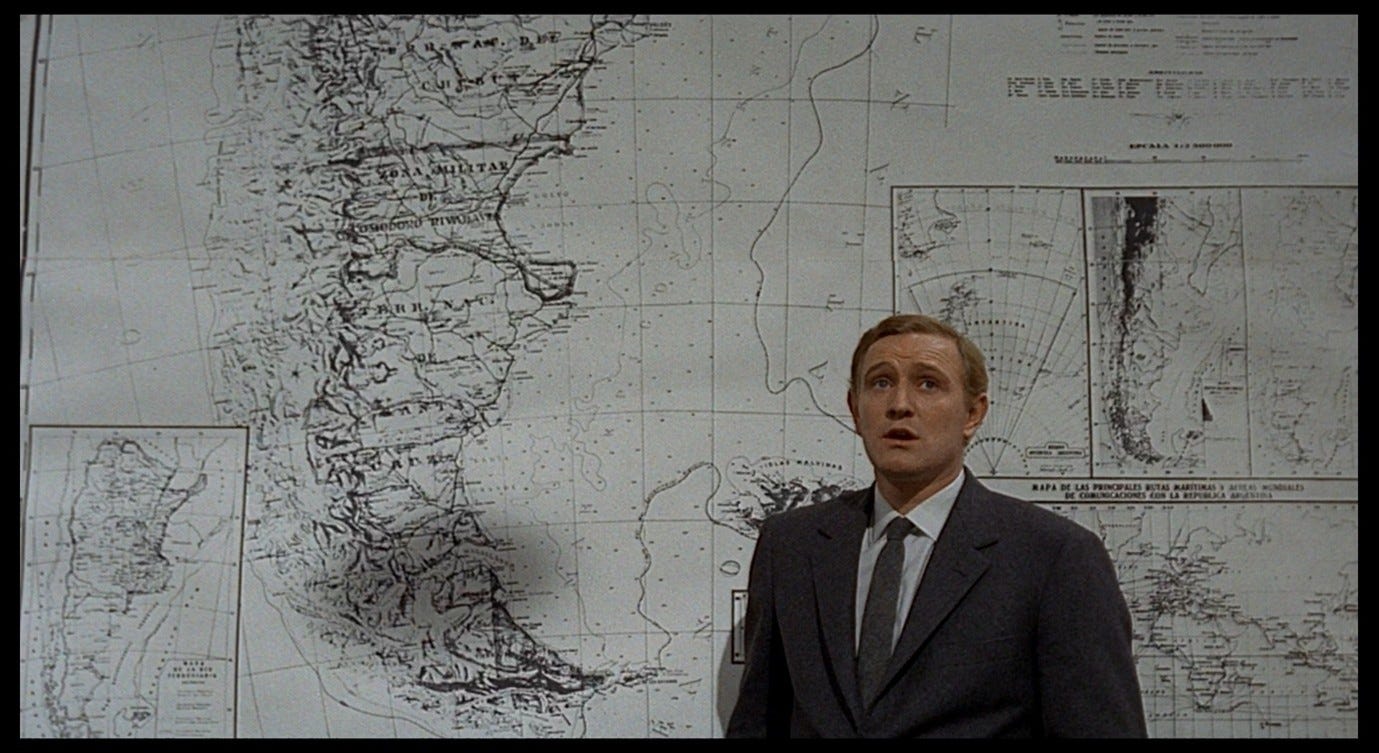

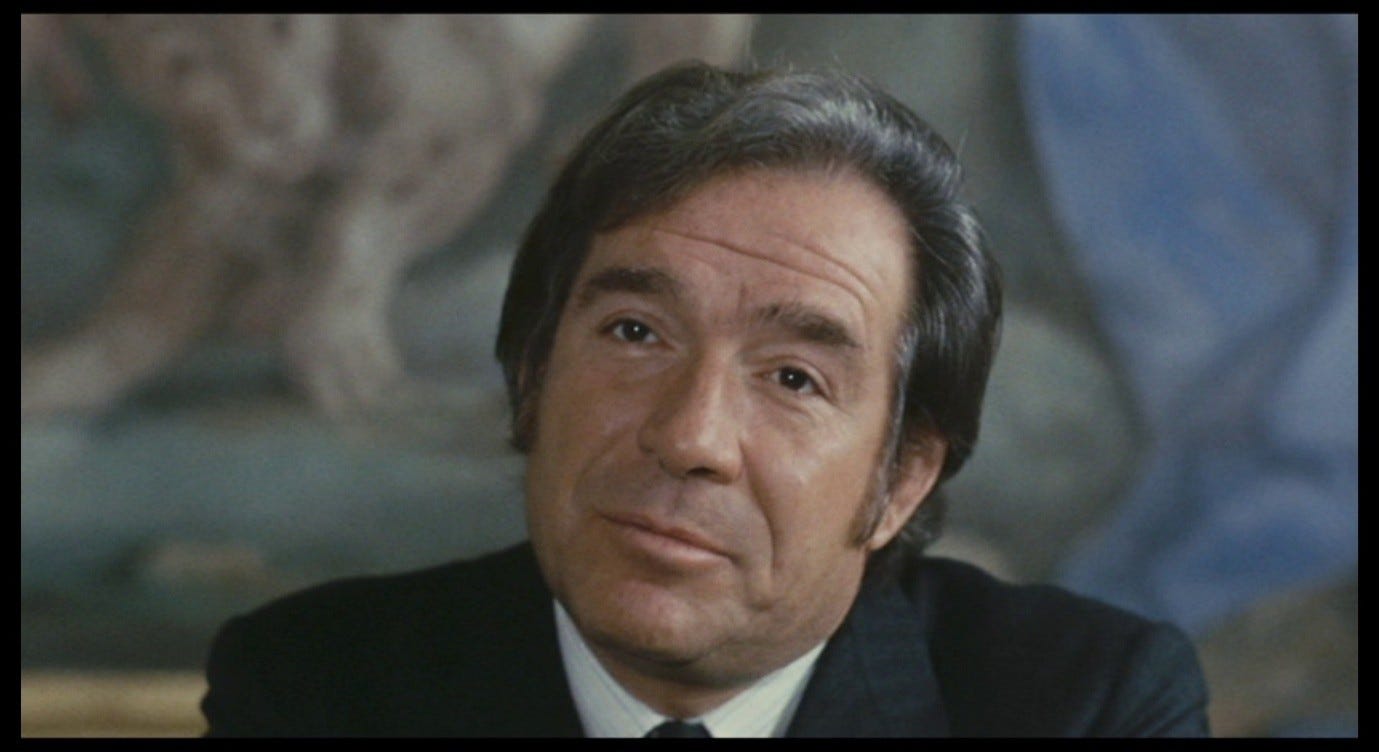

In Part 27, we looked at the establishing shots of the briefing sequence, and the beginning of the tense dialogue between Corrado and the workers he has recruited for his South American enterprise. Something changes when Corrado is asked an especially difficult question: how long until the workers’ wives can join them in Patagonia? Corrado looks up as though calculating the amount of time, as though this issue had not already been decided and needed to be figured out now.

Perhaps he stalls for time because he knows his answer will not be well received. He tells the workers that they will have to wait at least a year, but they will be allowed one phone call per month in the meantime. We are reminded of Corrado’s conversation with Mario’s wife, in which he told her she could ‘eventually’ travel out to join her husband. She responded, glancing at Giuliana, by asking Corrado whether his wife would go with him. These two conversations also dovetail with the one on the SAROM rig about the things and people we take on our travels. The recurrence of this issue, in this moment, precipitates a breakdown in the orderly shot/reverse-shot structure of the briefing sequence.

A worker asks who will pay for the phone calls. We cut to a shot in which the recruits are out of focus in the foreground and a large wooden door is in focus in the background.

The door seems old and dilapidated, and above it we see (as the camera tilts upwards) splotches of white plaster, grey-and-brown stone, faded or half-scraped-off blue and light-blue paint, beige patches, scratches and cracks, and a tuft of old wires or cables jutting out of the wall.

During this shot, we hear Corrado’s voice answering the question – the company pays for one phone call a month, the workers can pay for any extra calls – but the camera seems to have lost interest in him and in the Q&A. We might assume that the shot represents Corrado’s point of view and that he is looking away distractedly while responding to the workers, but in the next shot he is looking in the other direction.

This resembles other disorienting moments, earlier in the film, in which the camera played a similarly ambiguous role, sometimes occupying Giuliana’s point of view, sometimes adopting a perspective of its own and exploring a space independently. I have noted before that the camera in Red Desert seems torn between empathising with Giuliana, coldly observing her, and even (at times) victimising her. It can make us see the world as she does or as the robots do; it can frame her as the only sane person in the room or as an indecorous embarrassment, or merely as an object among other objects. We are aware, by now, of all these perspectives and of the ways in which this film blurs them together.

In this case, the shot of the warehouse door and the cut back to Corrado looking the other way make us feel that the camera has become un-moored from the dialogic interactions in the Q&A, but then it seems to re-attach itself to Corrado’s point of view: he looks to his left, we cut to a panning shot that moves from left to right over the staring faces of the workers, and when we cut back to Corrado he is looking to his right.

That sense of being un-moored, created by the spatial confusions in the previous sequence of shots, is thus re-attached to Corrado: we were sharing his sense of spatial confusion, just as we sometimes share Giuliana’s feelings of being entrapped, examined, or dislocated thanks to the film’s strange editing choices.

The map is now out of focus behind Corrado and he seems not to hear the workers’ questions about getting Italian magazines in Patagonia. The screenplay describes his change of mood:

Corrado, whom we have seen behaving in a calm and somewhat detached manner throughout the discussion, now appears a little disturbed. His colleague responds on his behalf. […] Corrado experiences a sudden lack of interest in what is happening in the warehouse and starts looking at the surrounding objects [gli oggetti attorno], and the walls.1

In an interview with Jean-Luc Godard at the time of Red Desert’s release, when asked whether Corrado was meant to embody the ultra-modern ‘man of industry’ who is forging a new world, Antonioni denied this:

No, absolutely not. [Corrado] is an almost romantic figure, thinking of running away to Patagonia. He hasn’t the least idea of what he should be doing. He wants to go away; he thinks that in this way he will solve the problem of his life. But this problem is inside himself, not outside. In fact, meeting a woman is enough to make him doubt whether he really wants to leave. This encounter upsets him. […] He’s tired of all that talking. He’s thinking of Giuliana.2

Richard Letteri challenges the idea that Corrado is becoming preoccupied with Giuliana and that this is distracting him from the Patagonia project. Letteri argues instead that Corrado’s drifting gaze in the ‘briefing’ sequence embodies the cold, dehumanising eye of capitalism:

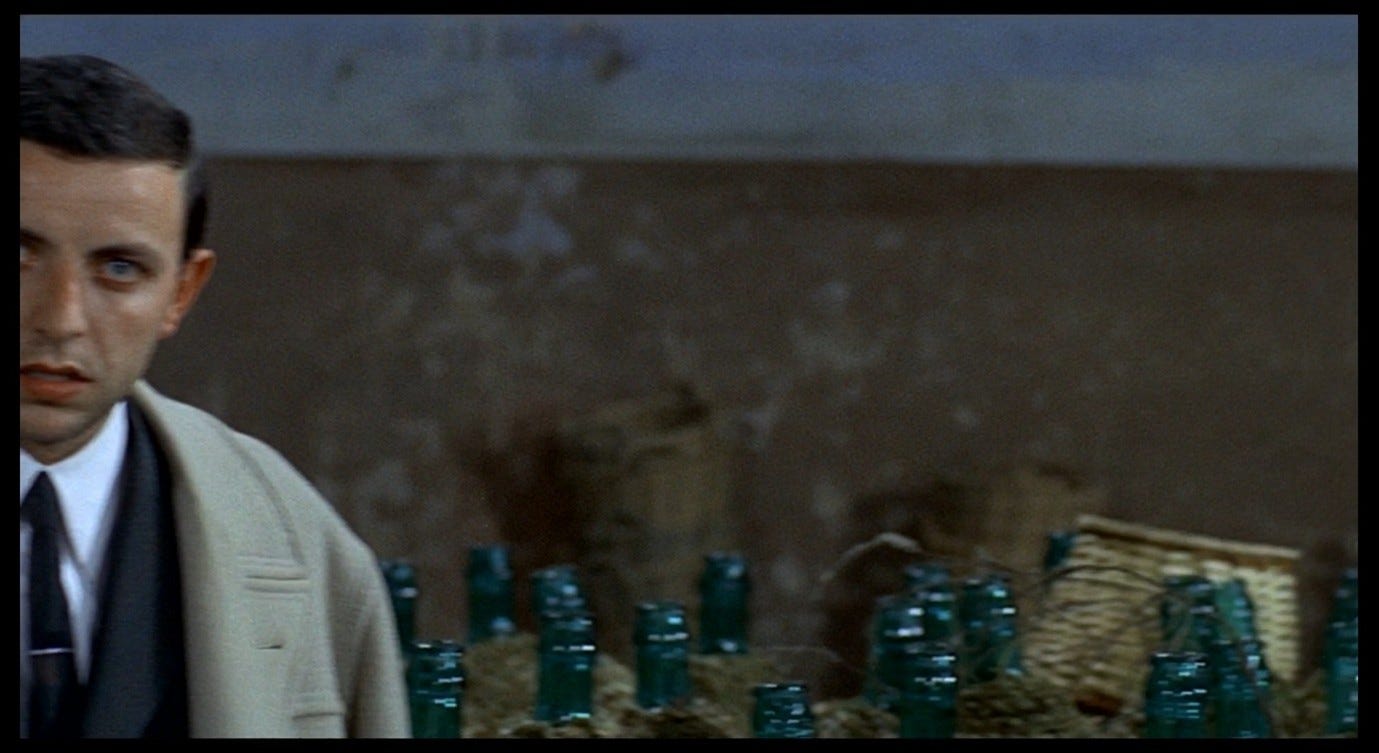

[A]lthough Antonioni claims that Corrado is drifting off to thoughts of Giuliana at this point in the meeting, [his] long shot of the workers surrounded by neat rows of demijohns followed by his point-of-view pan emanating from Corrado to the workers’ faces and then past the row of bottles suggests that Corrado’s vision is fully immersed in the capitalist axiomatic which renders workers and commodities alike in terms of their exchange value.3

However, these two readings are not mutually exclusive. Corrado’s gaze blurs the distinctions between people and objects, and this reflects the exploitative nature of his work. As Letteri points out, Corrado will end up ‘seducing’ Giuliana in a similarly exploitative way4 (to the point that we should arguably see his action as rape rather than seduction). But the rendering alike of workers and commodities is also a symptom of Giuliana’s illness. Part of Antonioni’s point, in the Godard interview, is that Corrado is not simply ‘drifting off to thoughts of Giuliana,’ but beginning to see the world as Giuliana does: beyond simply being attracted to her and wanting to have sex with her, he has been infected by the things she has said to him. We should remember Vittoria’s meditation in L’eclisse: ‘There are days when holding a needle, a piece of cloth, a book, a man…is the same thing.’ There is a strong relationship between this sentiment and the dehumanising capitalist gaze Letteri identifies in the sequence of shots we are looking at. Pasolini suggests something similar in Pigsty, when the industrialist Herdhitze proudly foresees a future where ‘there will be no trace of humanistic culture, and men will no longer have problems of conscience [problemi di coscienza].’ His Utopia is a world where people will be nothing more than pigs in a pen, or less than that – food for pigs, to be consumed and forgotten and never mentioned again.

But Pigsty is also about the personal crisis between Julian (like Corrado, an industrialist’s son expected to take over the business) and Ida (like Giuliana, a critic of industry, though a more politically engaged one). When we see the young lovers arguing back and forth, we think of Herdhitze and Klotz arguing back and forth.

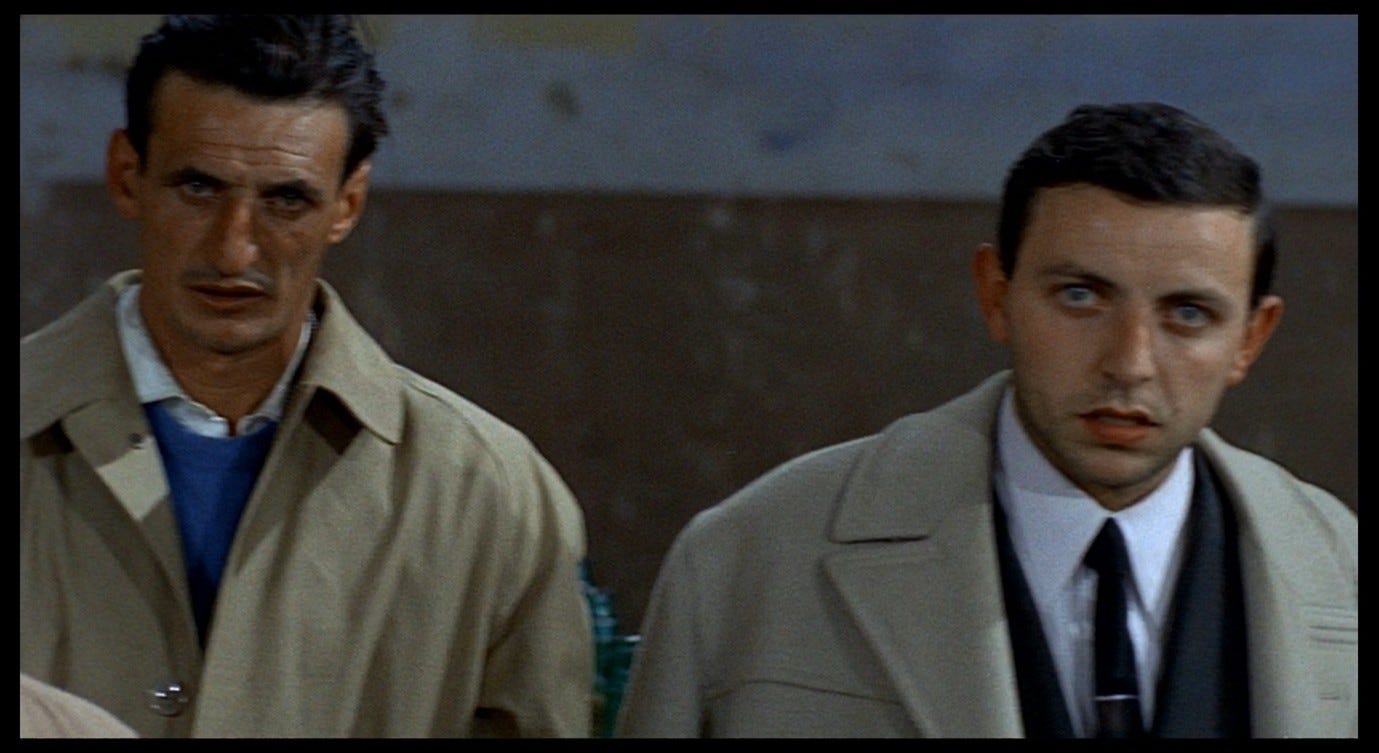

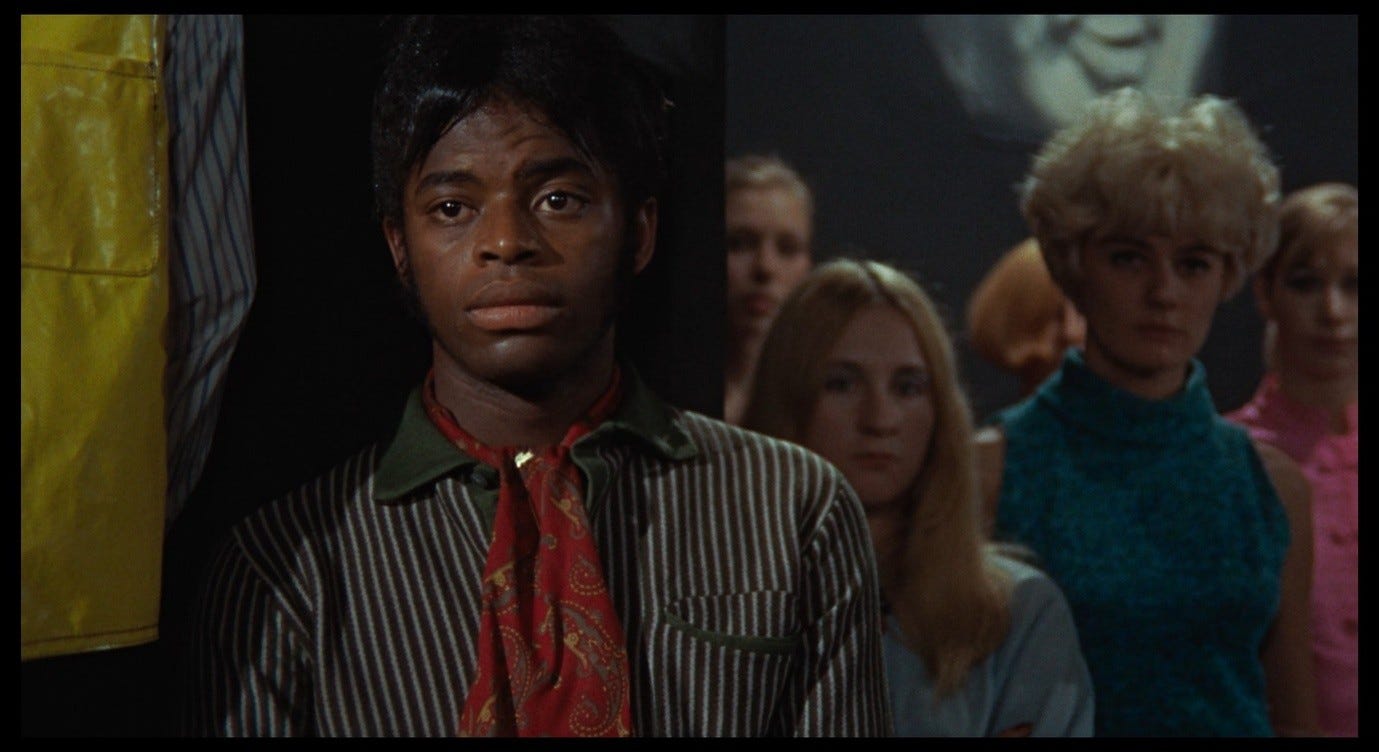

When Corrado looks at the men he is exploiting, he thinks of Giuliana and how her condition echoes theirs (and, in a way, his own). In the panning shot that scans the workers’ faces, the most striking face is that of the disgruntled young employee we saw in the background earlier.

Because he is wearing the exact same expression of sneering resentment as when we last saw him, there is a tension between the intensity and the stasis of his emotions. He looks as though he were on the verge of shouting at Corrado or attacking him, but he is perpetually on that verge and never crosses it. In ‘reality’, on the film set, Antonioni has told him how to look and told him to maintain that look in every shot, and the performer is doing a good job of performing his role. Perhaps the consistency of this performance makes us aware that these are non-professional actors and that Antonioni is giving them very precise, prescriptive directions; Richard Harris, a professional actor, walked off the set and refused to film his final scenes because he was fed up of receiving such prescriptive directions, unaccompanied by explanation or discussion. In this panning shot, we are seeing ‘real’ people, but also people treated as objects, required to behave like objects within a carefully composed image. These workers have a vividly unhappy and exploited look about them, but this look also seems like a pose they have been ordered to adopt. (I may be underestimating the agency of these non-professional actors: perhaps, like Tanino, the sneering young man showed a natural talent for making such faces, and Antonioni simply made use of this talent.)

As the camera pans to the right, we quickly leave behind the three disgruntled faces and spend several seconds scanning a row of empty demijohns in wicker baskets.

The shot draws an association between the gaping mouths of the two men in the back row and the open spouts of the glass bottles. These are all empty vessels in different senses: the workers have needs to be fulfilled (that probably will not be fulfilled) and functions to fulfil (that inevitably will be fulfilled); from the company’s point of view, they are vessels in the service of the liquid petrochemicals that will be the lifeblood of this project. On the soundtrack, we hear the workers voicing their desires for media and entertainment (they want magazines, television, topless women), while Corrado’s colleague reminds them they will be in Patagonia to work, not to be amused. The workers see themselves as consumers, the company sees them as consumables, and in this moment the film sees them as a mixture of both – and as something else that is harder to define.

In addition to the politicised critique (of Corrado and the company) that Letteri finds here, there is also something of Giuliana’s critical gaze in these images of the workers among the demijohns. The men seem too posed, too static, impossible to engage with – like the worker whose sandwich Giuliana purchased at the start of the film, with whom she was unable to communicate beyond that awkward economic exchange. In the panning shot in the warehouse, the men’s faces occupy a space in the frame that is then left glaringly empty. Where there were human heads, there is now nothing, and below that there are the open spouts of the demijohns. These spouts are like gaping mouths but also like necks without heads attached. We feel an emptiness where the heads should be, a loss of humanity in the image. But we also see, in this empty space, an echo of the emptiness in the workers’ faces. There is a persistent ‘nothingness’ in these images, whether they have human faces in them or not.

There is a similar effect in a crowd scene in Blow-Up. When the photographer searches the audience at the Yardbirds concert, he finds a roomful of spectators who are – with the exception of one dancing couple – completely immobile, as though they were posing for (or trapped inside) a photograph.

When Jeff Beck smashes his guitar and throws its neck into the crowd, these spectators spring into motion, each one frenziedly trying to grab this priceless object. The photographer happens to catch it himself and escapes onto the street with it, only to discard it as soon as he realises the crowd has stopped chasing him. A stranger picks up the guitar neck, then discards it again.

The behaviour of the concert audience is disturbingly unified: they are programmed to listen in complete stillness, like the mannequins outside the club, except for the couple who are programmed to dance; they are all programmed to scramble for the guitar-neck when it is thrown at them; but none of them really cares about or is engaged by any of this. There is an assumed ‘value’ in attending the concert but no one is enjoying it. There is an assumed ‘value’ attached to owning the guitar-neck but it is a commodity without any real use – you might keep it because you care about the Yardbirds, but outside the concert no one does, so it is just another piece of trash. Peter Brunette sees this as an illustration of ‘[t]he importance of context and framing in the establishment of meaning,’5 and Juli Kearns builds on this idea when she locates the guitar-neck scene in the larger context of the film:

And so it is too with Thomas’ transformative experience [in the park] which, at least physically, has only left him with a token that no one else can decipher, in which no one will see the same material as he does, its meaning lost upon others. It becomes a useless artifact even to him outside the club.6

This is a very significant connection to make, because the remaining token of the Maryon Park murder is an image of the upper part of a corpse, cropped from the lower part and – thanks to this editing process – blown up beyond recognition, so that it no longer represents a head or a human.

Like the relic from Jeff Beck’s guitar, it seemed in its earlier context to be superlatively meaningful, but in its isolated, decapitated state, it is just visual noise on photographic paper.

The disembodied guitar-neck and the headless demijohn-necks are both images through which Antonioni expresses a sense of lack, or removal, or dis-memberment. Like Giuliana, we find ourselves asking, ‘What should I look at?’, and with her eyes we look for something that is not there anymore – we find something missing. Giuliana experienced this most intensely in the ‘lost in the fog’ sequence on the pier, when she watched the four human figures standing inertly (like the factory workers and the concert audience) and staring at her, or at nothing, before they were obliterated entirely by the mist.

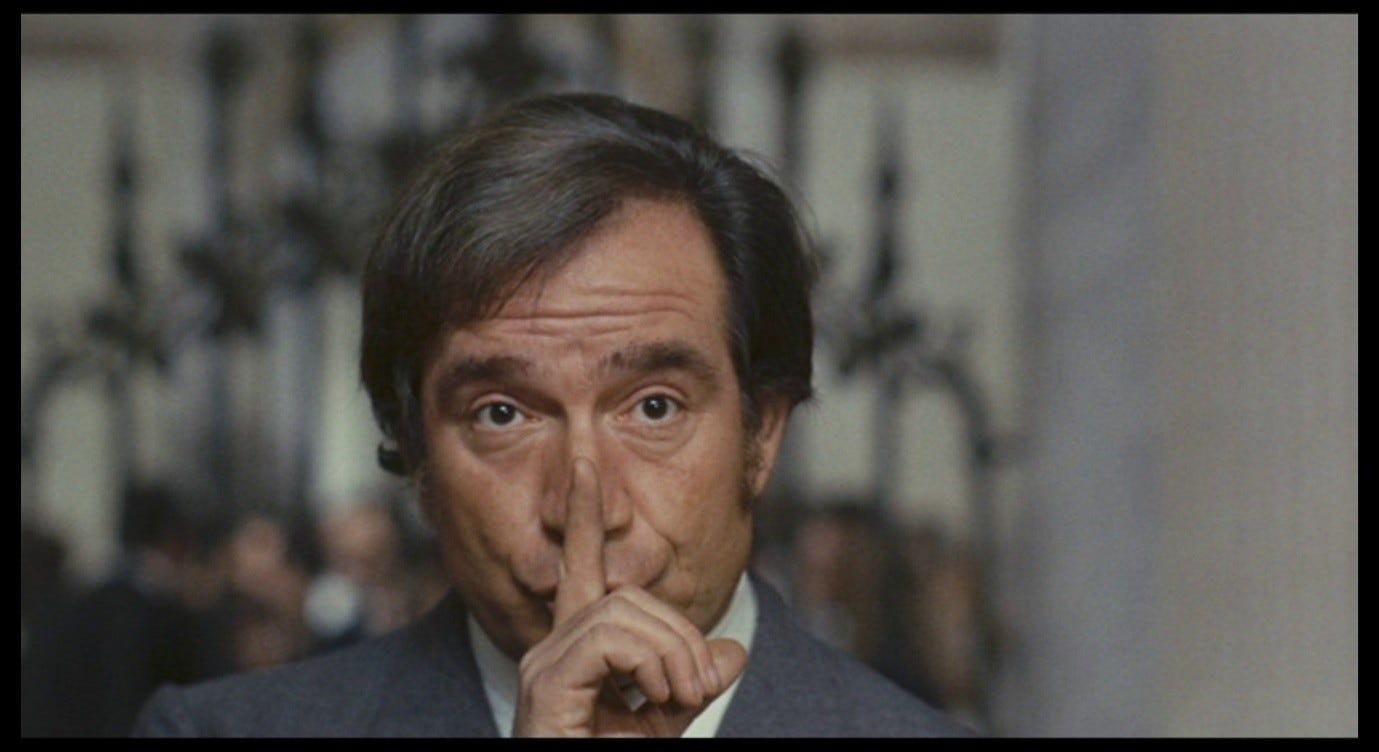

Something was missing from those people. They were not quite there, even before the mist rolled in. Now, as he briefs the workers, Corrado seems to have a similar experience. We cut back to him after the panning shot, his eyes now looking to the right, the map still out of focus behind him, an inscrutable look on his face.

What he sees is like what Giuliana saw in the fog, but unlike her he does not appear to react with anxiety and terror. Instead, there is a kind of wry cynicism in his look as he slowly takes in the scene before him.

The tone of his look, and of this whole sequence, reminds me of how Chantal Akerman looks at New York in News From Home. Her camera rigorously pursues de-humanising effects, divesting the images of any sense that they are (or should be) focused on people. We see a woman on a street corner, slightly out of focus; the focus keeps shifting as though threatening to make her the protagonist of this scene, but she always reverts back into an anonymous haze.

A man on the subway sees Akerman’s camera, stares at it for a while, then moves into another carriage to ensure that this strange woman’s film – whatever it is about – will not be about him. By the end of the shot, we can only see his hand clinging to a distant pole.

We watch the subway carriage doors open at a stop, and no one gets on or off the train: in the absence of any human interest, this moment is (at least for me) about the striking blue pillar on the platform.

As the train starts to move again, I notice the other blue pillars racing by, then the dark blueness in the tunnel outside and the blue of the cigarette advert reflected in the window.

When we reach another stop and the doors open again, it is not the people that seem to be missing – it is a relief that they remain absent – but the blue pillar. The image seems deficient without it.

At the stop after that, we are rewarded with a large blue wooden panel on the wall - an improvement on the pillar, a pleasant surprise - only slightly tarnished by the humans who come between us and it.

The film displaces our interest away from people and towards the inanimate world around them, much as Antonioni did at the end of L’eclisse or (using colour to draw the eye) in Red Desert.

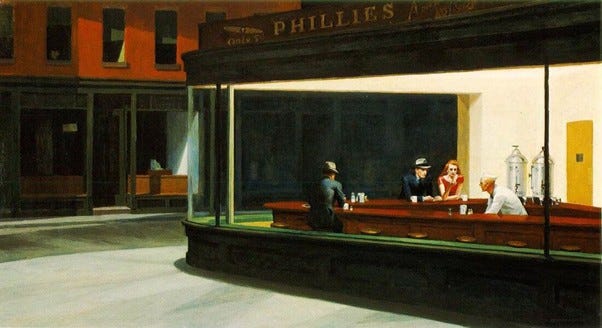

On the soundtrack of News From Home, Akerman reads letters from her mother, who is back at home in Belgium. The mother complains relentlessly about Akerman’s letters to her: there are not enough of them, they are not informative enough, they all say the same thing. We never hear Akerman’s letters, but the film represents a kind of response to the mother. ‘I live to the rhythm of your letters,’ Natalia tells her daughter. As we watch the film, we experience New York to the rhythm of the mother’s letters, and the letters to the rhythm of New York; at times, the noise of the city mingles with and drowns out the voiceover. Natalia is glad to hear her daughter is not lonely, but the images conflict with the lies Akerman is sending home. Not even in Taxi Driver or Eyes Wide Shut has New York been transformed so vividly into a landscape of the mind, a desert space isolated from the rest of humanity. We see a diner like the one in Edward Hopper’s ‘Nighthawks’,7 but this one is closed and empty and juxtaposed with frighteningly loud traffic noises from outside the frame.

In the final minutes of News From Home, the voice of Akerman (and her mother) disappears from the soundtrack, and we travel by an unseen ferry into the harbour, withdrawing slowly from the city. The cityscape drifts away from us, deeper and deeper into a cloud of fog-and-smog that obscures the tops of the Twin Towers.

This is ‘home’ now: the film’s title is in English, locating home in New York, or at any rate in a place divorced from the language of Akerman’s family home. Her news, communicated to her mother through these images, is that her life is drifting further and further away, into a lonely de-humanised fog. Her mother can complain all she wants. There is literally nothing to write home about.

Akerman’s perspective and that of her mother are like Corrado’s and Giuliana’s, in that they haunt each other and are ambiguously in conflict but also blurred together. We see New York as Akerman sees it, but also as her mother imagines it, and as Akerman imagines it, and as Akerman imagines her mother imagines it. ‘He wants to go away; he thinks that in this way he will solve the problem of his life,’ said Antonioni of Corrado; ‘he doesn’t realise that the problem is inside himself, not outside.’ The encounter with Giuliana triggers his dawning realisation, in the briefing sequence, that his constant changes in ambiente storico are a distraction from an interior problem. Akerman seems to say to her mother, ‘This is how I see and experience New York, not as a new place but as a manifestation of something inside me.’ In the final moments of the Red Desert briefing sequence, Corrado will see and experience his surroundings as a manifestation of something inside himself, and specifically of something that causes a rift between him and other people, shifting them out of focus and out of his field of vision.

Next: Part 29, What Corrado sees and feels.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 483

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; pp. 291, 295. In the French text, Antonioni says that Corrado is trying to resolve ‘le problème de sa vie.’ Taylor translates this as ‘his existential crisis,’ but I have opted for a more literal translation here. French text from Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘La nuit, l’éclipse, l’aurore’, in Cahiers du Cinéma 160 (November 1964), pp. 8-17; p. 15.

Letteri, Richard, ‘Becoming Giuliana: Antonioni’s Red Desert and the Capitalist Social Machine’, Deleuze and Guattari Studies 15.1 (2021), pp. 91-116; p. 100

Letteri, Richard, ‘Becoming Giuliana: Antonioni’s Red Desert and the Capitalist Social Machine’, Deleuze and Guattari Studies 15.1 (2021), pp. 91-116; p. 97

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 117

Kearns, Juli, ‘Analysis of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up’, Idyllopus Press, Part 4

Hopper, Edward, ‘Nighthawks’ (1942), Friends of American Art Collection, image from edwardhopper.net