Everything That Happens in Red Desert (40)

What happens to Giuliana?

This post is primarily focused, from the outset and throughout, on the topics of emotional/physical abuse and rape. It also contains spoilers for A Day in the Country, The Red Shoes, and The Double Life of Véronique.

This scene in Red Desert has not, to my knowledge, been interpreted as a rape scene before. Framed in this way, some of the images reproduced below may be upsetting, but I have included them because they are crucial to the analysis of the scene. For the other films discussed, I have not included images that depict rape.

Antonioni admitted, in two separate interviews, to having abused Lucia Bosè (with whom he was in a relationship at the time - she was 19 and he was 38) on the set of Story of a Love Affair:

In the screen test, she revealed a dark and disturbing aura – which was very appropriate for the part. […] She was enchanting, intelligent, sharp, cheerful. Oh, how many blows poor Lucia had to take for the final scene! The film ended with her beaten up and sobbing, leaning against a doorway. And yet she was always happy, and it was difficult for her to pretend to be desperate. She was not an actress. To obtain the results I wanted I had to use psychological and physical violence. Insults, scolding, abuses, and hard slaps. In the end, she broke down, crying like a little baby. She played her part wonderfully.1

I had to use a different approach, which turned out to be helpful, even if it might seem – and maybe even is – mechanical and hideous. On the one hand – by resorting to events and feelings that had nothing to do with her character – I took apart her natural and youthful cheerfulness in order to create within her a state of mind suitable to the scene that she had to act out. On the other hand, I shook her up and got her excited. [The interviewer asks: ‘I have heard talk of slaps – is it true?’] Yes. I hope Lucia has forgiven me. I didn’t like to have to do that, but there was no other way, nor did she have any other technique to rely on.2

In a well-functioning film industry, such behaviour would at least get the director fired, and as I said in Part 11, it may put you off watching Antonioni’s films or continuing to read this blog.

I am not against ‘cancel culture,’ and to be honest it is hard to reconcile my attachment to Antonioni’s films with my knowledge of his behaviour. In what follows, I will not make any excuses for him, nor will I separate the art from the artist: rather than distinguishing the compassionate film Red Desert from the cruel behaviour of its director, I will make the case that the film contains something of that cruelty.

In earlier posts, I have talked about ‘my Red Desert,’ my preferred version of the film which is committed to ‘taking Giuliana’s side’ and asking the audience to identify with her. The hotel-room scene, as I experience it, is like something from a horror film, and specifically a horror film that sympathises with its protagonist. But in this post, I also want to explore a darker layer of this sequence, which is brought into focus by Antonioni’s admissions of abuse, by some of his other comments about this and other films, and by the ways in which critics have responded to the hotel-room scene.

I find this very difficult to write about, partly because it is a complex topic with many (sometimes contradictory) dimensions, but also because it entails discussing sensitive issues such as abuse and rape.

As a straight, white, cisgender man, and one who has no experience of being sexually harassed, sexually assaulted, or raped, my perspective on these issues is in many ways limited. As a lifelong devotee of classic films, I have a tendency to be defensive about these ‘great works of art,’ whereas others who are less invested in their greatness might reasonably see them as products of abusive men in an abusive industry, deserving of neglect rather than the breathless praise heaped on them by blogs like mine.

For what it’s worth, my intent in this blog is not really to celebrate Red Desert or Antonioni, but to try and communicate what happens inside me when I watch this film, and especially to explore those aspects of it that I find challenging. Even when I lapse into calling it a ‘great film,’ which I generally try not to do, this is a reductive way of saying that it provokes thoughts and emotions in me. For example, Red Desert (and Antonioni’s other films) helped me through a period of suicidal depression. This does not make me idealise Red Desert. Indeed, the film helped me because it is a powerful illustration of some of the social forces that have contributed to making me such a lonely, depressed individual, and even (strangely) because it is complicit in some of those forces. This troubles me, but I also learn something important from it.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s definition of story-telling is relevant here:

One person writing in a quiet room, trying to connect with another person, reading in another quiet – or maybe not so quiet – room. Stories can entertain, sometimes teach or argue a point. But for me the essential thing is that they communicate feelings. That they appeal to what we share as human beings across our borders and divides. There are large glamorous industries around stories; the book industry, the movie industry, the television industry, the theatre industry. But in the end, stories are about one person saying to another: This is the way it feels to me. Can you understand what I’m saying? Does it also feel this way to you?3

I am not an artist and this blog is not exactly a story, but I am writing all of this in order to say, to you, ‘This is the way it feels to me,’ using Red Desert as a sort of conduit for expressing these feelings. Ishiguro’s heart-warming definition of art becomes more problematic when the ‘person writing in their quiet room’ is a film director exploiting and abusing people, but I think the definition is still useful in this context. I want to talk about how it feels when I engage with Red Desert on this level because this is important to me personally, but also because, in a more general sense, I think these are important issues to talk about. I hope that what I say will resonate with you. Whether you agree or disagree with my take on Red Desert, I would love to hear your reactions in the comments section below, or through a direct message; any criticisms are welcome.

I have not heard any stories of on-set abuse regarding Red Desert, or regarding Antonioni’s relationship with Monica Vitti, but we only know about his treatment of Lucia Bosè because he volunteered the information in interviews. I have no reason to think that this behaviour was atypical for him, or that he did not abuse or coerce people in less obviously violent ways at other times. His problematic behaviour also has a bearing on his portrayal of sexuality. During the making of Beyond the Clouds, Wim Wenders expressed concern over sex scenes that were, by his account, uncomfortable for the actors to film and uncomfortably pornographic to watch in their unedited form; he observed that Antonioni seemed to derive some gratification from filming these scenes.4 Some might argue that Antonioni’s debilitated, post-stroke condition (he could barely speak) should mitigate our judgement about this behaviour, but I do think that ‘leering’ tendency is already visible in Blow-Up, and that even the less graphic sex scene in Red Desert may be read as a would-be titillating portrayal of rape. Murray Pomerance quotes a contemporary report by Jeanne Molli, from the set of Red Desert:

Due to the love scene with Monica Vitti, members of the crew are already convinced that one result is certain. Every Italian spectator worth his salt as a male – and there are no Italian males who think they are not – will leave the theater in hot pursuit of the nearest neurotic woman he can find.5

Perhaps Antonioni would have disapproved, or perhaps these crew members were just giving an accurate report of the mood on set. I find it hard to imagine that anyone is turned on by this scene in Red Desert, as it appears in the finished film, and in the below analysis I will not ‘make the case’ for this kind of interpretation. In line with Ishiguro’s ‘this is how it feels’ formula, I would read the objectifying gaze of the camera in this scene as a component of Giuliana’s environment, and would read it as more clinical and critical than sexualising as such. But others may legitimately find something creepier in this scene, and (to reiterate the trigger warning from the top of this post) the images below may be more disturbing in this light.

As a way into analysing this sequence, let’s consider the relationship between Antonioni’s descriptions of on-set abuse and his conception of women as ‘subtle filters of reality’:

Women perhaps have a more subtle, more sincere way of filtering reality. Women instinctively possess an acumen that men don’t. They’re less hypocritical. Men are forced by their jobs, and by the daily relationships that they have with other men, to control themselves, to tone down their reactions, to hide their feelings. Women, less so. Of course, I could be wrong. Nevertheless, as a man, every day I am forced, often with a certain amount of surprise, to note how much more clear-sighted women are than men, and often how much braver they are too.6

The problem with Lucia Bosè was, according to Antonioni, her lack of talent for hypocrisy, which amounted (in his eyes) to a lack of acting talent. She was happy and could not pretend to be sad; women express emotions directly and sincerely; so she had to be made genuinely miserable in order to perform as required. When Antonioni calls his approach ‘mechanical’ he is admitting to a kind of hypocrisy, and a kind that many artists engage in when ‘obtaining the results they want.’ Andrei Tarkovsky orchestrated and filmed the agonising death of a horse in order to lament the cruelty of humanity in Andrei Rublev, and Ken Loach decried corporal punishment by inflicting such punishment on actual children in Kes. Antonioni’s intent in Story of a Love Affair was, as he said:

to examine the individual himself, to look inside the individual and see, after all he had been through (the war, the immediate postwar situation, all the events that were currently taking place and which were of sufficient gravity to leave their mark upon society and the individual) – out of all this, to see what remained inside the individual. […] And so I began with Story of a Love Affair.7

Paola’s devastation at the end of the film is a vital element in this project, as is Guido’s impassivity. She senses the disintegration of their relationship and is fully overwhelmed by her emotions; he shuts down, lies to her, and disappears. This, the film implies, is the state of play in human relationships in 1950. It is painfully ironic that Antonioni inflicted trauma on an otherwise happy person in order to ‘describe’ the profound unhappiness of his time. He saw it as his job to ‘create within her a state of mind suitable to the scene that she had to act out,’ just as he would later paint (and thus pollute) the landscapes of Red Desert in order to make them ‘act out’ scenes of environmental devastation.

This is a paradoxical conception of art, in which the (male) artist engages in constant hypocrisy – planting evidence and then pretending to discover it – but depends on the (female) actor’s sincerity. The emotion is what the film is about: not the causes of that emotion, as we saw in Part 38, but its symptoms and effects, the ways in which it is acted out. The point is not to trace these feelings back to their origins in the war, in the post-war recovery, or in the slaps and insults inflicted on the actor just before the cameras roll. The point is to conjure that sincere, direct filter of reality on the cinema screen, by any means necessary, so that it can express the emotions that the hypocrite-artist himself cannot.

The abusive hypocrisy Antonioni displayed on Story of a Love Affair casts a kind of gloomy light on the portrayal of abusive behaviour in his later films. The men in these films are seen, for the most part, with a clear and critical eye, and the women’s emotions are centred and taken seriously. But there is, in these men, something of the Antonioni who resorted to ‘hideous and mechanical’ means to force an expression of emotion in Lucia Bosè, and there is something of Bosè in these women, who seem burdened with a trauma that is not exactly theirs – that has been imposed on them. At the end of La notte, when Giovanni rapes Lidia in the sandpit while she says, over and over again, ‘You don’t love me! Say it!’, we feel that she is confronting him with a reality he refuses to see, and that the rape is expressive of that refusal. It stems from Giovanni’s profound denial of reality, from his lack of self-awareness. Here too Antonioni spoke of hypocrisy, but also seemed to want to redeem Giovanni:

The man becomes hypocritical, he refuses to go on with the conversation because he knows quite well that if he openly expresses his feelings at that moment, everything would be finished. But even this attitude indicates a desire on his part to maintain the relationship, so then the more optimistic side of the situation is brought out.8

The camera drifts away from the sandpit as if there were nothing to see here, making itself complicit in Giovanni’s hypocrisy and refusing to acknowledge the end of the relationship; but it also seems to take Lidia’s side in affirming that, whatever Giovanni says or does, ‘everything is finished.’

The hotel-room scene in Red Desert is in some ways more straightforwardly critical of the abusive man, and more ‘on the side of’ the woman he is abusing. This is how Antonioni described it:

I would like to emphasize one moment in the film which is intended as a criticism of the old world. When the woman, in the middle of her crisis, needs help, she meets a man who takes advantage of her [profite d’elle] and her crisis. She finds herself face to face with the old things [vieilles choses], and it is these old things which agitate her and overwhelm her.9

This frames the sexual encounter between Giuliana and Corrado in unambiguously negative terms. It does not say whether the sex is consensual or not, and does not explicitly define what happens as ‘rape’ – this issue is buried in the allegorical reading about being overwhelmed by vieilles choses – but it draws a very clear distinction between what Giuliana wants or needs and what Corrado does. By using the language of profit and crisis, Antonioni recalls Mili’s bitter remark about Max, the predatory industrialist: ‘He’s like a crow. Always ready to swoop down on a bankrupt factory or a woman in crisis.’ In Antonioni’s description of Corrado’s behaviour, there is little sense that this character ‘means well,’ or that he accidentally does more harm than good. Corrado sees Giuliana’s crisis as an opportunity and he profits from it.

Critics have often tried to read this scene in more positive, or at least more ambivalent terms. The sexual encounter is sometimes described as ‘love-making,’ as in Robin Wood’s account:

Corrado makes love to Giuliana because she is on the verge of insanity. […] Antonioni […] sees him merely as ‘taking advantage of her’ […] but it is at least as valid (and the two views, though seemingly contradictory, are not incompatible) to see his actions as motivated by an extreme protective tenderness which is as much concern for his own vulnerability as for hers.10

The two views expressed here – of Corrado taking advantage and Corrado being protective – are not incompatible because, Wood implies, the protectiveness is itself deeply self-interested, and is a way of taking advantage. This tortuous effort to make Corrado more sympathetic turns back in on itself and reaffirms the point Wood is ostensibly challenging. In doing so, it captures something about how Antonioni sympathises with (or tries to sympathise with) his male characters, in a way that contradicts his hyper-critical attitude towards them and yet somehow is not incompatible with it.

The stage directions for the hotel-room scene, in the Red Desert screenplay, mark this quite clearly as a rape scene (though without using the word ‘rape’), while also introducing some more ambiguous elements that chime with Wood’s reading:

Corrado, for his part, embraces her and begins to caress her tenderly, as though to calm her down [come per calmarla]. But then his gestures, previously hesitant, become more purposeful [acquistano una sapienza precisa, literally ‘take on a specific wisdom/awareness’], his caresses become increasingly overt [esplicite]. Giuliana is not even able to notice. So when Corrado lays her on the bed, she lets him do it and is inert. Corrado begins to kiss her. Giuliana’s entire body is in spasm. A kind of frenzy, an unconscious fornication [impudicizia incosciente], mixed with impulses of resistance and discovered pleasure [piacere scoperto].11

The first two sentences in this paragraph are a kind of microcosm of Corrado’s relationship with Giuliana. He embraces her tenderly at first, as though to calm her down, but the phrase come per indicates that this is an interpretation, an appearance, like the superficial protectiveness that Wood identified and that turns out to be something else. Corrado’s behaviour then becomes more transparent. The sapienza precisa referred to in the next sentence is both Corrado’s awareness – he knows what he is doing – and ours, as his esplicite actions no longer challenge our capacity for interpretation. His seeming tenderness and desire to ‘calm’ Giuliana (throughout the film) have led to this moment when his actual intentions are revealed. It is not that Corrado is a moustache-twirling villain with an intricate plan to rape Giuliana, and I think he has complex motives for pursuing her; but sexual desire is one of his key motives, he has been gradually trying to ‘seduce’ Giuliana, and in this moment he decides to consummate that long-term project.

There is a striking irony in the above-quoted passage from the screenplay: when Corrado’s motives become more explicit, Giuliana herself is unable to share in this sapienza precisa. At this point in the scene, she does not notice what he is doing. Following her ‘streets, factories, colours’ outburst, Giuliana has embraced Corrado frantically, not with any hint of erotic desire, but more like someone who feels themselves collapsing and is trying to stay upright.

Then, in the reverse-shot (the same camera set-up as the one where he told her to calm down and asked what she was afraid of), we see Corrado seamlessly transition into erotic caresses, and he begins to remove her clothes.

While he does this, she conspicuously fails to respond in kind. Her head and arms writhe about and her hands occasionally make gestures as though to say ‘stop.’

When Corrado forcibly lowers her onto the bed, she throws her head back and we see a brief flash of her bared teeth. We cut on this action to a closer view of her face (with Corrado’s obscured by the red bar) staring up at us, her mouth opening.

The screenplay describes this in terms that, problematically, suggest a mixture of inertia, resistance, and enjoyment: the stage directions say that she ‘lets’ Corrado do this to her; that the act of fornication is unconscious (incosciente) for her; that she also resists him with some of her gestures; and that to some extent she is ‘discovering’ some pleasure through this experience. The finished film does not explain Giuliana’s emotions to us in this way, but leaves us to interpret what we see. When she bares her teeth or her mouth gapes, or when her hands tense and curl around Corrado’s body, the spectator has the option of interpreting these gestures (at least some of them) as evidence of that piacere scoperto the screenplay refers to. Seymour Chatman grapples with this problem in his conflicted analysis of this scene:

In II deserto rosso, sexuality is a palpable mechanism of neurotic relief. At her most desperate moment, not knowing where else to turn, Giuliana goes to Corrado’s hotel room. In an ecstasy of ambivalence, she both fights him off and embraces him. And she does experience some relief, however fleeting. […] [Corrado] does his best to be supportive, but he […] cannot resist sexual temptation, nor does he bother to ask whether lovemaking is the appropriate response to her writhings, which may be expressions of anguish and not sexual at all. The look on his face seems to say, ‘Let me take care of your problem: “masculinity” knows best.’12

These statements, from two different chapters of Chatman’s book, are contradictory: sex is a ‘palpable mechanism of neurotic relief’ and Giuliana’s resistance/acceptance of Corrado is summed up as a kind of ‘ecstasy’ which soothes her; and yet Chatman recognises the lack of consent in this encounter (Corrado ‘does not bother to ask’) and notes that Giuliana’s ‘ecstasy’ may instead by ‘anguish’. His comment about sex being a ‘mechanism of neurotic relief’ for a woman enjoying an ‘ecstasy of ambivalence’ arguably sounds like the masculinity-knows-best voice he later ascribes to Corrado.

Christine Henderson argues that Giuliana

reaches for Corrado just as, with equal force and indecision, she pushes him away, trying to negotiate the conflict between her desire to fuse with him, to seek an erotic containment, and the annihilating threat that his desire poses to her fragile sense of subjectivity.13

Peter Brunette similarly finds a ‘delicate ambiguity as to whether she actually wants to make love with Corrado,’ but goes on to say that the scene

raises the question of what it would mean for someone as disturbed as Giuliana is to ‘want’ anything. In her state, is it possible for her to be responsible for her acts? The elliptical cutting signifying the passage of time also extends the ambiguity to the point that it is not clear exactly what has taken place here.14

I think Henderson and Brunette overstate and understate (respectively) Giuliana’s agency in this scene. Henderson frames Giuliana as sending out mixed messages, reaching for Corrado but also pushing him away, ‘with equal force and indecision’: she really wants to make love to him but also really does not, and her indecisiveness is evidence of the ‘fragile subjectivity’ that she needs to strengthen. Brunette frames her as being so disturbed that she is beyond ‘wanting’ anything, beyond any form of responsibility, and this explains the disturbed editing of the scene which renders it unaccountable, illegible. I do not think that Giuliana ‘reaches for Corrado’ in the sense of trying to initiate sex with him, and indeed she shows herself more than capable, at several moments, of expressing what she does not want. But again, these critics are picking up on something that is in the film, namely its ambivalent attitude towards Giuliana.

In one type of precedent for scenes like this, the woman would be framed as repressed and frigid, and the man would force her to ‘discover’ the pleasures of sex. Boudu Saved from Drowning and Gone with the Wind both show a woman being raped and then ‘awakening’ afterwards with a look of ‘discovered pleasure.’ Both films play into a long tradition of rape narratives, in which women discourage their male suitors but ultimately succumb and are ‘better off’ for it. This rape myth serves the interests of the perpetrator’s desire, while disingenuously claiming to benefit the victim as well.

In A Day in the Country, Henriette tries to fight Henri when he embraces her on the river-bank, but then she pauses and suddenly kisses him back. Here too there is a kind of rape-myth propaganda at work: Henri is simply taking the relationship where it needs (or ought) to go, consummating their love even though unjust circumstances mean they cannot be together in the long term. Henriette resists strenuously because the morality of her culture (a different manifestation of those vieilles choses) tells her this is wrong, but when she ultimately ‘gives in’ this is, the film asks us to believe, expressive of what she truly wanted all along. Years later, when Henriette is married to the repugnant Anatole, she sees Henri nearby and seems to grieve for the lost happiness he represents.

Her ‘discovered pleasure’ turns to sadness now that it has been cruelly buried by the demands of her bourgeois existence. Despite some differences, we are dealing here with the same rape myth as in Boudu: the woman’s resistance is still seen as a denial of something inevitable and necessary (and pleasurable), and the film is critical of the social conventions that necessitate this resistance.

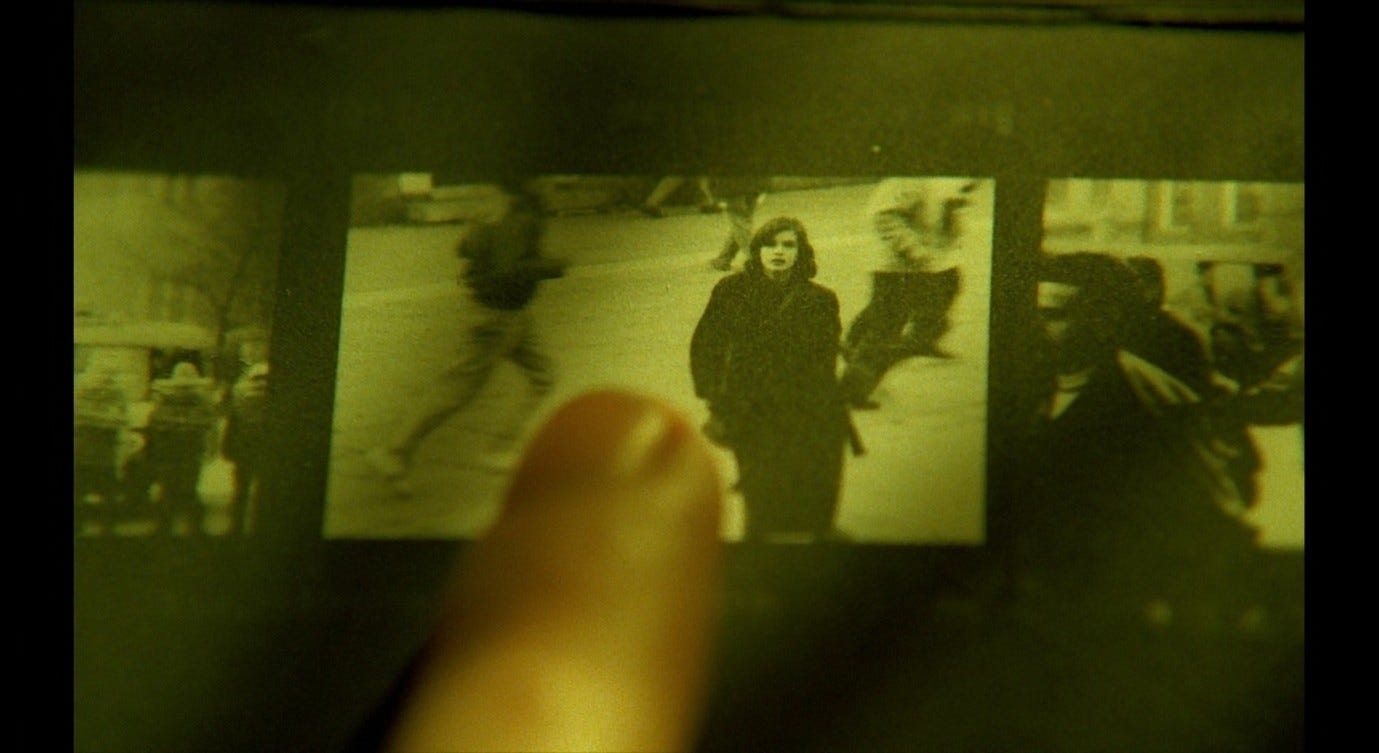

The Double Life of Véronique presents a more complex version of this trope, and one that bears a closer resemblance to the sex scene in Red Desert. Alexandre, the puppeteer, courts Véronique in ways that he intends to be romantic, but that ultimately come across as sinister. This pursuit culminates with the two having sex in Alexandre’s hotel room, in a context where Véronique does not initiate or (I think) want a sexual encounter. Indeed, like Giuliana, she is profoundly upset. She has just discovered an image of her other self – Weronika, her Polish alter-ego – in a set of holiday photos. Seeing this image, Véronique realises that her recent, inexplicable feeling of loss must have been a response to this alter-ego’s death. That sense of loss flared up in her, earlier in the film, while she was making love to her previous boyfriend. She sent him away in order to be able to process this feeling alone. Now, in the hotel room with Alexandre, she fully realises the nature and cause of her grief, while he (without getting consent) obliviously has sex with her.

As in the other examples discussed here – and again, problematically – there is an emphasis on ‘discovered pleasure,’ and in this case we see Véronique have an orgasm. But her pleasure is highly ambiguous, as is the relationship she has begun with Alexandre. For one thing, Véronique’s attention is absorbed by the picture of her ‘other self’ during this sex scene, like Mavi looking into the mirror in Identification of a Woman. There is a link between Véronique’s orgasm (the petite mort) and the ecstatic, ultimately fatal pleasure Weronika took in singing - the moment pictured below is the one just before her on-stage death.

To reach this extremity of emotion entails both a fulfilment of the self and a loss of the self: it completes her and it destroys her. Véronique has always been comforted by the feeling that she is not alone in the world, but when it turns out that this feeling reflected her awareness of the unknown ‘twin’ in Poland, she realises that the sudden loss of this feeling must have been caused by Weronika’s death. In short, this is the moment when she realises she is alone in the world, when that recently discovered loneliness is validated. When the feeling began, she sent her boyfriend away; when the feeling becomes an inescapable fact, she is raped by Alexandre. The rape coincides with the moment when reality forces itself upon Véronique. The ‘other’ really is gone, and she is truly alone.

Kieślowski allows for a certain amount of ambiguity about Alexandre’s intentions, or about whether this relationship will be fulfilling for Véronique. At times, the film might seem to suggest that Alexandre has been sent by the universe to make up for the death of Weronika, and that when these two have sex this marks Véronique’s acceptance of loss and her progression to a new, truly fulfilling relationship with another ‘other’. Various supernatural signs and coincidences seem to lead Véronique to Alexandre, as though the spirit of her alter-ego were encouraging her to pursue this relationship. However, upon seeing the holiday photo from Poland, I think Véronique realises that those signs – insofar as they were supernatural – were not intended to couple her with Alexandre or to mark him as her soul-mate. Rather, he is the instrument through which the existence of the alter-ego is revealed, as he is the one who points out Weronika in one of the photos. Just as his value to her is purely instrumental, so Véronique is only important to him as a sex-object and a source of material to feed his work. When she learns that he began communicating with her as a kind of experiment, to test out a story he was planning to write, she temporarily shuns him. At the end of the film, when he reveals his creepy Weronika/Véronique-inspired twin-puppets, she realises that her instincts were correct, and that he is still just using her. The story he intends to write about her has the same title as the film we are watching, exacerbating the sense that Véronique is trapped in an exploitative construct.

In a conversation between film critic Tadeusz Szczepański, screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz, and director Krzysztof Kieślowski, a provocative connection is drawn between Alexandre, God, and (implicitly) the film-maker:

Szczepański: [The] puppeteer is also a metaphor for God. And it turns out that God may be malign, cynical. […]

Piesiewicz: Of course, it was not the case that we wanted to show a great guy with whom a girl falls in love. If there is a person who performs tricks and brings inanimate objects to life and creates such a situation that we start to believe that dolls are alive, then we assign to him certain attributes…

Kieślowski: Of a manipulator, for instance.15

The director, too, uses tricks to make us believe that the personnages on the screen are real, and as with Alexandre those tricks can entail manipulation or outright abuse. The film’s ending is not entirely bleak, but Véronique does appear to leave Alexandre for good, and there is a strong sense that she will now have to come to terms with her new-found solitude. Kieślowski filmed but then abandoned an ending in which Véronique is seen reuniting with her father. Instead, on the verge of arriving at his house, she reaches out to touch a tree, as if to affirm a sense of connectedness that does not depend on human relationships, or on any definable bond with another person. Perhaps it is telling that her decision also prevents the film from resolving, from becoming a completed work of art.

The rape scene in Red Desert explores many of the same issues as the one in Véronique. Giuliana too grapples with a feeling that she is both ‘never alone’ and ‘completely alone’ at the same time. She is confronting a sense of alienation, not only in her relationships with other people, but in her relationship with the entire universe. In her outburst to Corrado, she expresses this more clearly than ever before: her reasons to be fearful accumulate until she screams out the word tutto, and this is the moment when Corrado crosses the line and begins to rape her. She has already told him, as Lidia told Giovanni at the end of La notte, that he does not love her (Giuliana phrases this as a rhetorical question), but now she is telling him something else. Nothing loves her, nothing loves anything, everything is a threat. Her not-aloneness does not entail the existence of a cosmic twin, but is rather like being attached by interdependent puppet-strings to every component of her ambiente.

Giuliana’s bodily reactions to Corrado follow on seamlessly from her outburst of terror, and from the existential crisis we have seen brewing in her up to this point. She wants her loved ones around her like a wall; but a wall would never come closer to her or touch her; but a wall would also be a claustrophobic prison… She feels hemmed in and threatened by all the people and things in the universe; but she wants to be at one with that universe; but she is also terrified of dissolution… If, as the screenplay suggests, and as some critics have concurred, Giuliana can sometimes be understood as expressing pleasure (as well as pain) in this scene, this ambivalence reflects her anguish over her own desires, her way of loving, her need for other people. However, it is an open question whether any of her gestures do convey pleasure, or whether they merely appear to because of cultural preconceptions (not least those perpetuated by the movies). In one shot, we see Corrado from behind while Giuliana’s arms reach over his shoulders. One arm stops writhing, relaxes, and settles tenderly, as though in acceptance of Corrado’s love-making.

This moment invokes another rape trope, familiar from A Day in the Country, On the Waterfront, and other films where the woman fights the man off but eventually succumbs and wraps her arms around him. In Red Desert, if we have been paying attention (in this scene and in the film as a whole), we will be too familiar with Giuliana’s spasmodic gestures – the way she alternates between frenzied movement and inertia – to interpret this one simplistically. Her arm, in fact, does not settle but continues to writhe. In the reverse-shot that follows, we see Giuliana herself (not just her arm), and she seems disturbed and confused. If we felt, for a moment, that we were seeing another iteration of that resistance/acceptance cliché, this feeling is quickly undermined by the camera’s renewed attention to Giuliana’s facial expressions.

At this moment, the oscillating hum intensifies on the soundtrack. Giuliana moves away from Corrado to close the wardrobe door, as if this might stop the noise – but it does not, and she turns to look in our direction.

Then we see what she is looking at: the window on the other side of the room with the white light coming through it (the yellow light comes through a different window).

Giuliana walks out ahead of the camera and opens the curtains. The camera follows until it is positioned behind her and just above her head, looking out of the window. Then it tilts down, leaving Giuliana herself at the very edge of the frame. Following the tilt, her reflection is visible in the window.

The view down to the street is intersected by criss-crossing wires, dividing the image into unequal quadrants. In one quadrant, an elderly man in a grey coat emerges and walks across the cobble-stones, with the aid of a walking-stick.

As Giuliana moves away from the window, we see her reflection passing through the right-hand quadrant, travelling in the opposite direction to that of the old man. Neatly framed within Giuliana’s quadrant are the black-bordered death notices, overlapping, partially torn, and crammed into a corner of the curved beige wall.

The old man outside is a variation on Tanino, the fruit-seller in the Via Alighieri, and the death-notices are a reminder of the ‘absolute zero’ into which Tanino was about to disappear (in Flavio Niccolini’s account; see Part 13). Niccolini also saw the old man as facilitating a ‘revelation of tragic truth,’ which is what Giuliana seems to experience again here. She comes away from the window looking profoundly depressed. The room itself seems to have darkened around her. The abstract painting on the wall expresses something like the loneliness of that image in the window.

The shapes in the painting are placed side by side but appear hopelessly separate, like the quadrants in the street-image, or like the two human shadows going their separate ways in their separate quadrants. The shapes in the painting are black-on-grey, like burnt, misshapen corpses laid out on the ground. The black shadow of the old man walks through a grey world, and the posters on the wall (seen from such a distance) make the dead seem anonymous, identical, and interchangeable as they are plastered in overlapping layers onto this beige void.

Giuliana sits down despondently, staring into the middle distance. As we watch her, a grey shape looms into the left half of the frame: it is Corrado.

He sits down in front of Giuliana, but only when he reaches out to her does she notice him, and at this point she becomes alert again. She repeats the gesture I noted earlier, extending her hands with palms facing outwards, and now it is clear that she means ‘stop’: her wrists are pressed against Corrado’s shoulders, leaving her hands visible above them.

Giuliana’s gesture recalls a pivotal moment in The Red Shoes. During the Red Shoes ballet, Vicky faces the Shoemaker and clutches her red hair in terror. As she looks at him and the spotlight turns on and off, he transforms into Lermontov and then Julian, the two men vying for her allegiance.

Wearing the red shoes, in the fiction of the ballet, is somehow related to the opposing demands of ‘art’ (Lermontov) and ‘life’ (Julian). Like the evil Shoemaker, both men seek to control Vicky, and their unwavering ultimatums will drive her to her death. Just as the red shoes deprive the girl in the story of her agency, so Vicky’s feet will respond to these men’s demands by running (as though controlled by an external force) into death. But at this moment in the ballet, Vicky runs towards the image of Julian, colliding with it (the light goes off, rendering the image an insubstantial black void), then turning around and extending her hands with the palms facing outwards.

The gesture is directed both at Vicky’s ‘self’ (the self that occupied the position she was just in, which she is now facing) and at the two men she saw in this vision (responding to the blocking, domineering, predatory gesture they made with their arms). It is both a rejection – ‘keep away from me’ – and a plea for help – ‘save me’ – that encapsulates the complex triangulation of desire and dependency between Vicky, Lermontov, and Julian. Vicky’s final leap from the balcony onto the train tracks will display a mixture of agency and helplessness, so in this running-and-reaching-out gesture during the ballet, Vicky is both seizing control and succumbing to a vortex that drags her into another dimension.

Giuliana’s hand-gesture in Red Desert makes me think of The Red Shoes, partly because of the other allusions I identified in Parts 12 and 22, but also because that same combination of a rejection and a plea for help seems to be in play here. Giuliana puts her hands out against the ‘wall’ that is Corrado, wanting that wall to be there for her, supporting her, but also wanting to stop it from closing in on her. Earlier, in Mario’s apartment, we saw Giuliana move around the room and then address the space (on the sofa) she previously occupied, as she spoke about the ‘other woman’ in the clinic whose identity needed to be explained to her (by Giuliana). It was supposedly her mode of ‘loving’ that caused that identity crisis, that split in her self, and now in the hotel room her mode of loving and Corrado’s are in conflict. The doctors had warned her that she was loving in the wrong way, that she needed to love one single, discrete thing at a time. Vicky, in The Red Shoes, could not sustain an attachment to both Lermontov and Julian, could not (so she was told) be an artist and have a personal life, and needed to choose between them. Corrado too is imposing a specific kind of ‘love’ on Giuliana, perhaps believing that the specificity of having sex with one man will cure her of her everything-at-once emotional crisis. But Giuliana rejects this proposition. It is not the kind of help she needs, and if anything it will exacerbate her crisis.

Having made this ‘stop’ gesture to Corrado, Giuliana looks intently at him, searching his face as though trying to read it, or to reason with him. The reverse-shot of Corrado shows his face to be blank and implacable. He has taken off his grey sweater and his shirt is half-unbuttoned.

When he leans in closer, we cut back to Giuliana as she tries to get up, but Corrado holds her arms and makes her sit down again. Her searching gaze is more obviously hurt and confused now. Giuliana’s eyes look down at Corrado’s mouth, which is closing in to try and kiss her.

Her whole body then makes a sudden darting movement to the left of the frame, not unlike the darting movement with which she arrived in the hotel foyer, or the one we see in the next shot when her hand rushes in from the right-hand side.

As with her ‘stop’ gesture, these spasmodic movements represent both a flight away from danger and a flight towards refuge. So much of the danger that Giuliana faces has to do with ‘looking’: how Corrado looks at her, what she sees in his face, how the rest of the world looks at her, what she sees in the world around her. As in many earlier scenes, the camera is both a sympathetic witness who makes us see and understand Giuliana, and a persecutory voyeur who traps her within compositions that she is desperate to escape.

Giuliana escapes from the frame, disappearing to the left, only for the next shot to capture her hand entering from the right, extending horizontally along the red bar of the bed-frame. This continuity error creates a nightmarish effect, like leaving a room by one door only to find oneself entering it by another. Earlier in the scene, the red bar marked the boundary that Corrado had to traverse in order to reach Giuliana. Now, Giuliana herself is identified with this red line and seems to dissolve into it. The camera pans rapidly to the left as her arm shoots along the bar; the panning movement stops at the edge of the bed-frame where the red line turns downwards.

This is reminiscent of the shot in the warehouse (discussed in Part 29) when the camera looked at the ‘distressingly real’ recruit, then tilted upwards following the stack of baskets and the vertical trajectory of the blue line, eventually stopping when that line turned 90 degrees to the left. In that shot, we began with a human face, saw another face out of focus on the left of the frame, abandoned these men in favour of inanimate objects (the baskets), and finally left those behind in favour of a two-dimensional shape on a blank wall.

In the bed-frame shot, we also begin with a person, or a part of one. Having been ‘reduced’ to her legs by Corrado’s gaze earlier, now Giuliana is seen only as a hand lunging for safety. We glimpse her fingers, vanishing from the bottom-right corner of the frame as the camera pans, and as in the blue-line shot we seem to replace the person with an object, or with a shape.

The camera begins by representing and empathising with her feelings (the hand reaching out in terror), then leaves her behind as though it would rather look at the red bar, or as though it finds her trauma too intense to look at directly. This ambiguity was also part of the blue-line shot: that scene highlighted the exploitative nature of Corrado’s project and his inability to see the workers clearly, or to focus his attention on them. He and the camera are torn between seeing and not-seeing. As Giuliana makes this darting movement, the oscillating hum – which had faded away while she looked out of the window – returns jarringly on the soundtrack, accompanied by a pained grunt from Giuliana. These simultaneous noises underline the violence and the sense of danger in this moment, as well as identifying Corrado’s touch as the source of danger (recalling the earlier moment when the electronic hum seemed to flare up in response to his grabbing of Giuliana’s arm; see Part 38). With the red-bar shot, we move into a realm where ‘reality’ and spatial relations seem more confused than ever. In the next shot, Giuliana is lying across the bed, with Corrado’s hand entering from the left and creeping over her skirt to slowly pull the zip down.

At the same time, Giuliana lifts her head to look at the wall, where the out-of-focus stain continues to spread. Now there seem to be a mix of pinks and yellows in this stain, and when the camera tilts upwards we see (as in the earlier image of the stain on the ceiling) an ominous purple-black mass spreading out indefinitely into the upper part of the frame. More than ever, it looks like a bruise or a wound.

A disorienting cut transports us forward in time, to find Giuliana on the armchair where she broke down earlier. Corrado is approaching her. The room has become darker still, to the point that – in the next few shots – it will seem as though Giuliana and Corrado are inhabiting a pitch-black void.

The colourful stains on the walls and ceiling, and the darkness that makes them disappear altogether, are (like the electronic noises) evidently responding to the characters’ interactions. They are symptoms of something in the condition of this interpersonal relationship, and that something is becoming more intense and all-consuming. Corrado continues to grope Giuliana, but the camera stays focused on her: she writhes backwards in what seems like a gesture of pain and resistance, and for one haunting moment she looks directly into the camera. We see Giuliana in a way that Corrado does not, and she sees us looking at her.

It is worth asking what we ‘see’ here. I tend to draw out the empathic dimension of Red Desert – its focus on Giuliana and its serious engagement with her suffering – but the fact of Antonioni’s abusive behaviour, referred to at the start of this post, should prompt us to acknowledge another dimension of this film. Red Desert is a vivid and authentic portrayal of the ‘something terrible in reality’ that Giuliana will refer to in the next scene, but it also contains (rather than just portraying) that terrible thing. The film both empathises with Giuliana and keeps her at a distance; it is critical of Corrado but also looks at her through his cold, exploitative eyes. There is a part of Antonioni that sees Giuliana’s world as problematic, and that identifies with her inability to live comfortably within it. But there is another part of him that sees this world as progressing and developing in necessary and positive ways, and that blames Giuliana for not being able to keep up with it. In this latter sense, her resistance to the world around her is like the sexual resistance of Scarlett in Gone with the Wind and Madame Lestingois in Boudu: it is portrayed as a regressive denial of something inevitable. These two perspectives are in a constant state of tension throughout Red Desert, and neither is ever allowed to take over completely.

To return to the theme of hypocrisy, here is another revealing exchange from Antonioni’s interview with Charles Thomas Samuels:

Samuels: You mean, then, that it is man’s fault and not the fault of the environment that he can’t adjust, is miserable, etc.?

Antonioni: Yes. Modern life is very difficult for people who are unprepared. But this new environment will eventually facilitate more realistic relationships between people. For example, that scene [in Red Desert], that great puff of – not smoke – steam that blasts out violently between the two characters. As I see it, that steam makes the relationship more real, because the two men have nothing to say to each other. Anything that might crop up would be hypocritical.

Samuels: OK. But isn’t it also possible to say that they can’t speak to each other because their environment deprives them of an inner life to communicate?

Antonioni: No. I don’t agree. In that case…. Wait, let me think it over a moment. I think people talk too much; that’s the truth of the matter. I do. I don’t believe in words. People use too many words and usually wrongly. I am sure that in the distant future people will talk much less and in a more essential way. If people talk a lot less, they will be happier. Don’t ask me why. In my films it is the men who don’t function properly – not the machines.16

Antonioni’s reading of the steam-cloud sequence seems counter-intuitive. Has he forgotten that Ugo does talk during this scene, and that Corrado strains to listen to him, uncovering his ears having instinctively tried to protect them against the deafening roar?

Or does the film pass a kind of judgement on Ugo’s words by drowning them out, dismissing them as somehow ‘hypocritical’ and favouring the directness and sincerity of the steam-cloud’s soundtrack-devouring ‘aaaaahhhhh’? In any case, which relationship is made ‘more real’ by the drowning out of dialogue? Ugo’s with Corrado, ours with Ugo and Corrado, theirs or ours with the factory complex, or ours with Giuliana? As in Part 8, I would lean towards the last of these: we feel unmoored and without guidance, plunged into something against our will, unable to define our relation to what we see and hear. We cut from this scene to Giuliana waking up from her nightmare, as though the steam-cloud were the nightmare, and her dream-self had been screaming, ‘The factories, the colours, the people, everything!’

The portion of the hotel-room scene discussed in this and the next post is completely wordless. Giuliana’s ‘factories, colours, people’ outburst is the last line of spoken dialogue in the scene, and what follows is – for me – associated with the steam-cloud sequence. It is a wordless nightmare, an experience that cannot be captured in words, elliptical and in some ways incomprehensible. Just as Giovanni displayed hypocrisy in La notte when he raped Lidia, telling her to ‘Be quiet!’ to drown out her declarations of non-love, so Corrado displays a kind of hypocrisy in Red Desert, drowning out Giuliana’s attempts to verbalise her fears, imposing on her an overwhelming sensory encounter that, like the cloud of steam, will consume and transform her environment. The film shows this hypocrisy, and this act of rape, for what it is.

On the other hand, it says something about this scene that critics have tended not to view it as a rape scene, and that they have often defined Giuliana’s experience as one of mere disappointment in response to Corrado’s misguided attempt to help her. She runs to him for emotional support but is ‘[u]nconsoled by their lovemaking,’ as Millicent Marcus phrases it;17 ‘they make love,’ says Seymour Chatman, and ‘[t]hough that calms her for a moment, she leaves.’18 Giuliana has an anguish that cannot be consoled, an anxiety that cannot be calmed for more than a moment, and to some extent the film sees this as a failing in her. ‘Modern life is very difficult for people who are unprepared,’ says Antonioni; Giuliana’s affliction is incurable, she will never ‘function properly’ in the modern world. Corrado’s attempt to fix her, which Antonioni associates with the ‘old world’ and its ‘old things,’ fails in part because it bespeaks an attachment to outdated clichés (like adultery dramas and rape myths). In a way, as Corrado admits, he suffers from the incurable affliction too, albeit with very different symptoms. But I think the film is also, less conspicuously, frustrated with Giuliana in the same way that Ugo and Corrado are. This is the frustration of a man who does his job and plays his assigned role, with all the repression and hypocrisy demanded of him, and who ‘shakes up’ and abuses the person who is not performing adequately. He vaguely senses that this is a ‘hideous and mechanical’ way of treating people, but he treats them like that nonetheless – in fact, he resents them for inducing such confused feelings of guilt in him, as Corrado clearly resents Giuliana in his final scene.

Antonioni’s utopian reading of the steam-cloud sequence is indicative of his grimly optimistic attitude towards the future, his (partial) affinity for visions of progress that will transform us into better-functioning entities. Arguably, though, the cloud of steam has the opposite effect to the one he described. Rather than making any relationships ‘more real,’ it substitutes an overwhelming mechanical process for all possible relationships and feelings. It represents the hypocrisy of conflating people with machines, of pursuing the ends of industry (including the film industry) with a singleness of purpose that legitimises every kind of abuse and exploitation. In this light, the rape appears as the mirror-image of the steam-cloud. It is an expression, not of progress or modern industry, but of a deep-seated malattia dei sentimenti. ‘People talk too much,’ says Antonioni; ‘You think too much about your illness,’ says Corrado. Talk is hypocrisy, says this malattia we must not think about. There are certain things a person must do (don’t ask why), and if the person resists, they must simply be forced. Red Desert is, in my view, a powerful deconstruction of this hypocrisy, but it also has a certain amount of sympathy for it. This is one reason why the hotel-room scene becomes elliptical and, so to speak, uncommunicative, especially in its surreal conclusion.

Next: Part 41, The transformation.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Tornabuoni, Lietta, ‘Myself and cinema, myself and women’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 185-192; p. 186

Gandin, Michele, ‘Story of a Love Affair’ (trans. Dana Renga), in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 259-262; p. 260

Ishiguro, Kazuo, ‘Nobel Lecture’ (2017), available on nobelprize.org

Wenders, Wim, My Time with Antonioni, trans. Michael Hofmann (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), pp. 27, 31-32, 65, 132, 180

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 79

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘A documentary on women’, in Unfinished Business, trans. Andrew Taylor (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1998), pp. 111-115; pp. 113-114

‘A Talk with Antonioni on His Work’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; pp. 22-23

‘A Talk with Antonioni on His Work’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; p. 35

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 291. I am quoting primarily from the translation by Andrew Taylor, but also deviating from this based on the original French text in Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘La nuit, l’éclipse, l’aurore’, Cahiers du Cinéma 160 (November 1964), pp. 8-17; p. 15. For a fuller discussion of this original text, see Part 9.

Cameron, Ian, and Robin Wood, Antonioni (revised edition) (New York: Praeger, 1971), p. 111. The quoted passage is from the latter part of the book, which was written by Wood.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 493 (my translation)

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 59, 84

Henderson, Christine, ‘The Trials of Individuation in Late Modernity: Exploring Subject Formation in Antonioni’s Red Desert’, Film-Philosophy 15 (2011), pp. 161-178; p. 175

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 105

Bernard, Renata and Steven Woodward (eds.), Krzysztof Kieślowski: Interviews (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), p. 173

Samuels, Charles Thomas, ‘Michelangelo Antonioni’ (29 July 1969), in Encountering Directors (New York: Capricorn Books, 1972), pp. 15-32; p. 21. Also available via Scraps From the Loft.

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), p. 196

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 53