Everything That Happens in Red Desert (38)

Giuliana and her environment

In Part 37, I suggested that the image of Giuliana, seen from behind, kneeling beside the armchair, evoked an experience of loss or abandonment. For example, it somewhat resembles Frederick Elwell’s painting, The Wedding Dress, in which a woman kneels over her wedding dress beside an empty bed, presumably mourning the husband who died or the fiancé who abandoned her.1

The image of the kneeling Giuliana is a ‘painterly’ composition within a scene whose setting feels very deliberately and artfully composed. If the hotel reception was conspicuously blank and un-decorated, Corrado’s room is the opposite. Instead of the universal whiteness of the foyer, we have muted brown, beige, and grey colours, perhaps intended to help exhausted travellers rest and relax. The wooden (or wood-effect) panels along the walls create a sense of nature and artifice blended together, as does the artificial decorative bramble Giuliana fidgets with.

This moment recalls the way she ran her finger along the threads of the sofa-blanket in Mario’s apartment.

These are manufactured rooms and objects that evoke the natural world, on the basis that people want to remain connected to nature within their constructed living-spaces.

The hotel room is also decorated with conspicuous works of art. Two examples are of special interest: the abstract expressionist painting that faces the bed, and the tiny painting-on-wood (of a cluster of trees) that hangs by a black cord on the wall behind the bed.

The former depicts a row of unidentifiable shapes that seem at once related to and separate from each other, like a Rorschach test designed to trigger Giuliana’s anxieties about interdependence and alienation. The smaller painting’s dark-toned image of trees recalls the natural spaces blighted by carbon black from earlier in the film. The black cord and black frame might be associated with the black-framed death notices we see on the wall outside the hotel.

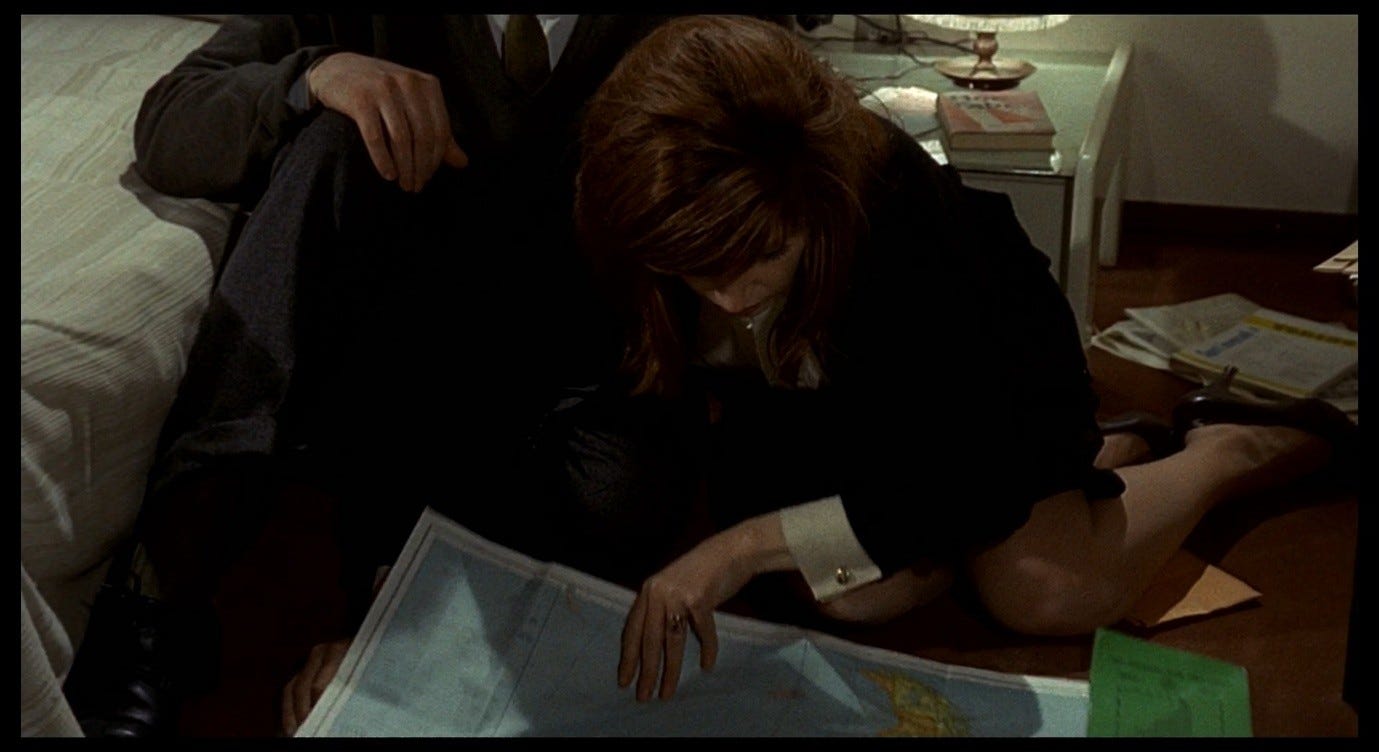

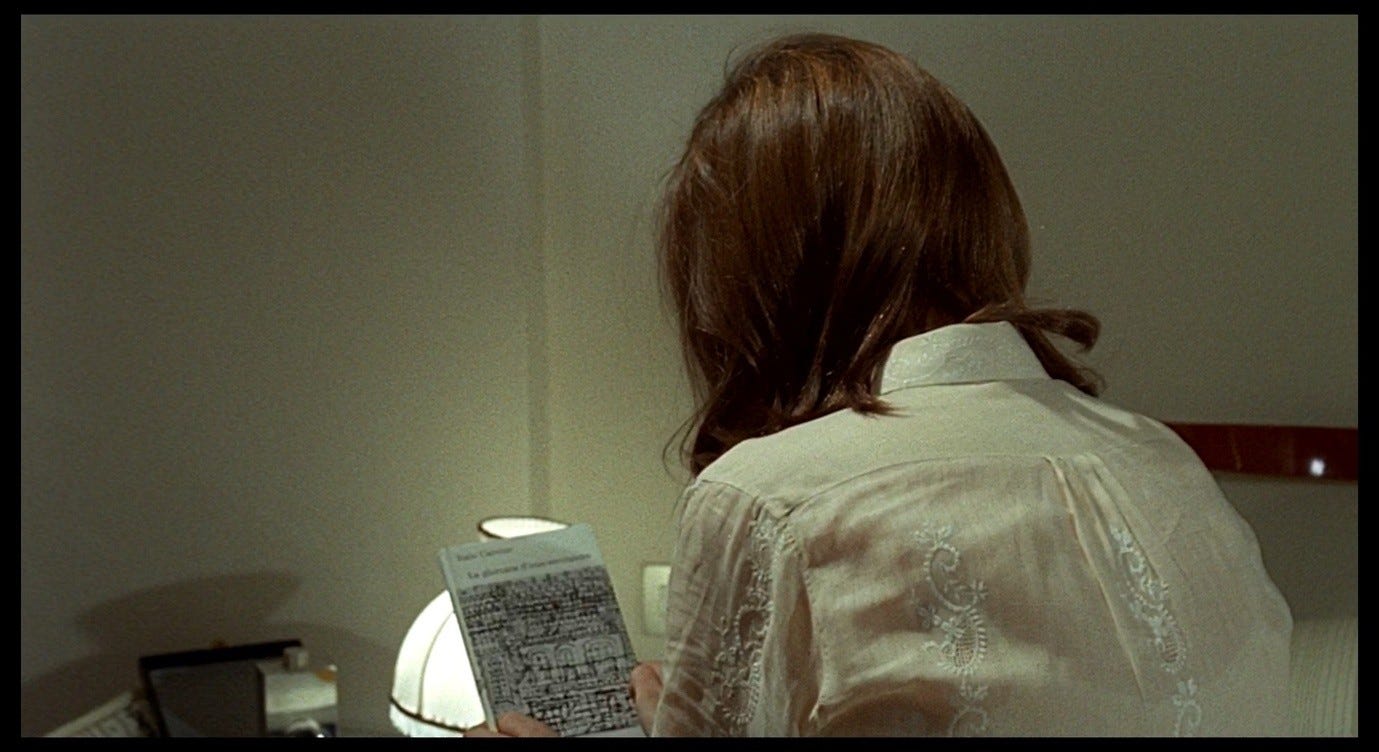

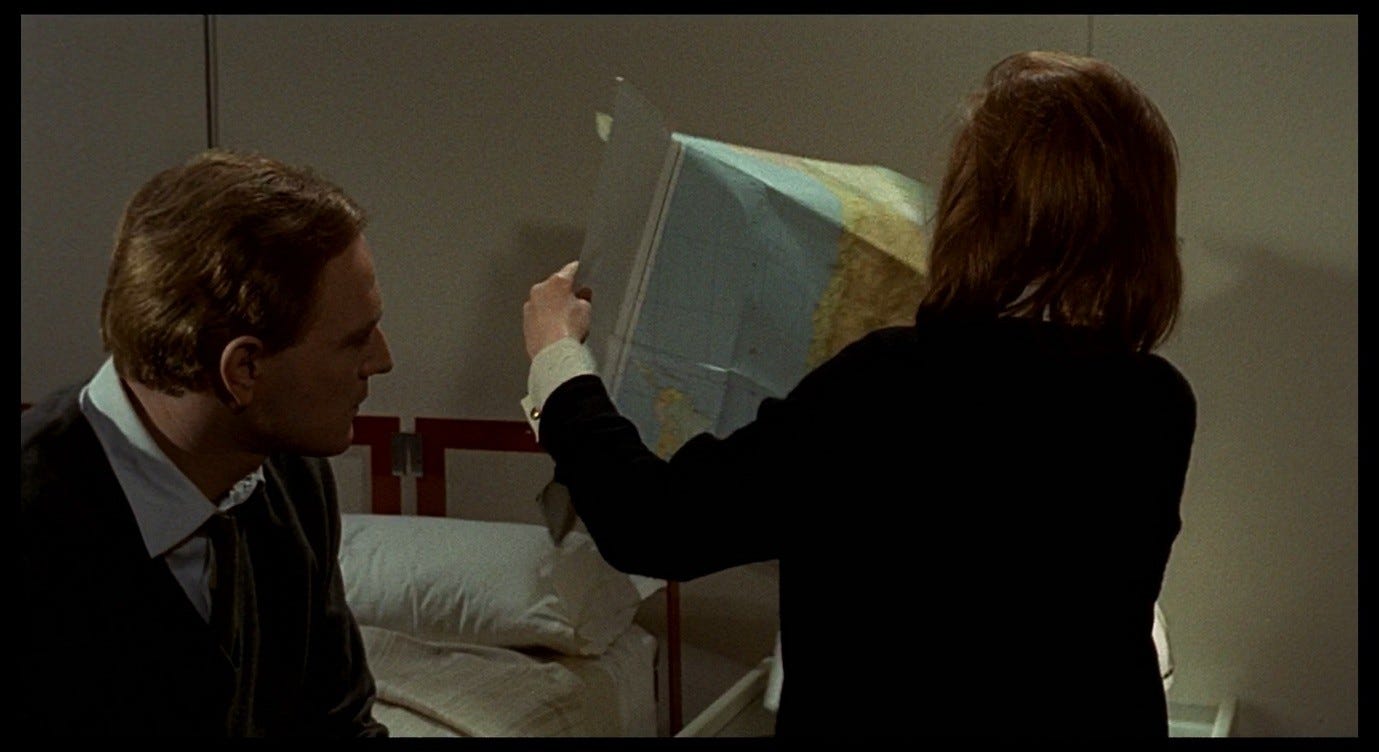

Besides these decorations imposed by the hotel management, Corrado has added to the bric-a-brac in this room by strewing his belongings all over it. As well as the clothes he has left lying around, there are also several books on the bedside tables, two of which are easily identifiable. I have referred to both these books (Homo Faber and The Watcher) in earlier chapters, and will look more closely at Homo Faber in Part 44. Between them, these books clearly had a formative influence on this film’s title, its themes, and especially the character of Corrado. It would only be a slight exaggeration to say that Corrado is an amalgam of the two protagonists in these books, or rather – as the placement of the books on either side of his bed suggests – that he is poised in between them, borrowing aspects of both. We see Homo Faber (Latin for ‘man the maker’) at the moment when Giuliana picks up the map of South America, reminding us of Corrado’s construction project.

We see The Watcher when she is on the other side of the bed, being watched by Corrado.

He is a faber and a scrutatore, he is the kind of perpetual traveller for whom these hotels are designed, he inhabits this space effortlessly: in short, he is in tune with his environment and its paraphernalia.

Giuliana, as we have seen repeatedly, is quite the opposite. Not only is she physically uncomfortable in almost any given space and unsure of how to interact with the objects within that space, she is also out of sync with the emotions and ideas that are implicit in these spaces and objects. When she and Corrado visited Mario’s apartment, the pink flowers outside seemed to be working with Corrado to impose a romantic, flirtatious tone on the encounter (see Part 16). Mario’s wife colluded in this as well by mistaking her visitors for a married couple. Giuliana subverted the ‘adultery drama’ clichés by focusing insistently on her illness, but there remained a sense that Corrado was preying upon her with the goal of seducing her. The same dynamic operates in the hotel room. Giuliana comes here looking for help, but what she finds is a space, and a person attuned with that space, that reinforce how un-attuned she is with this world. She is surrounded by forces that want to ‘reinsert her into reality,’ to make her ‘gears mesh’ in the way that they are supposed to, and what we see from our privileged perspective is that she continually resists and subverts these forces.

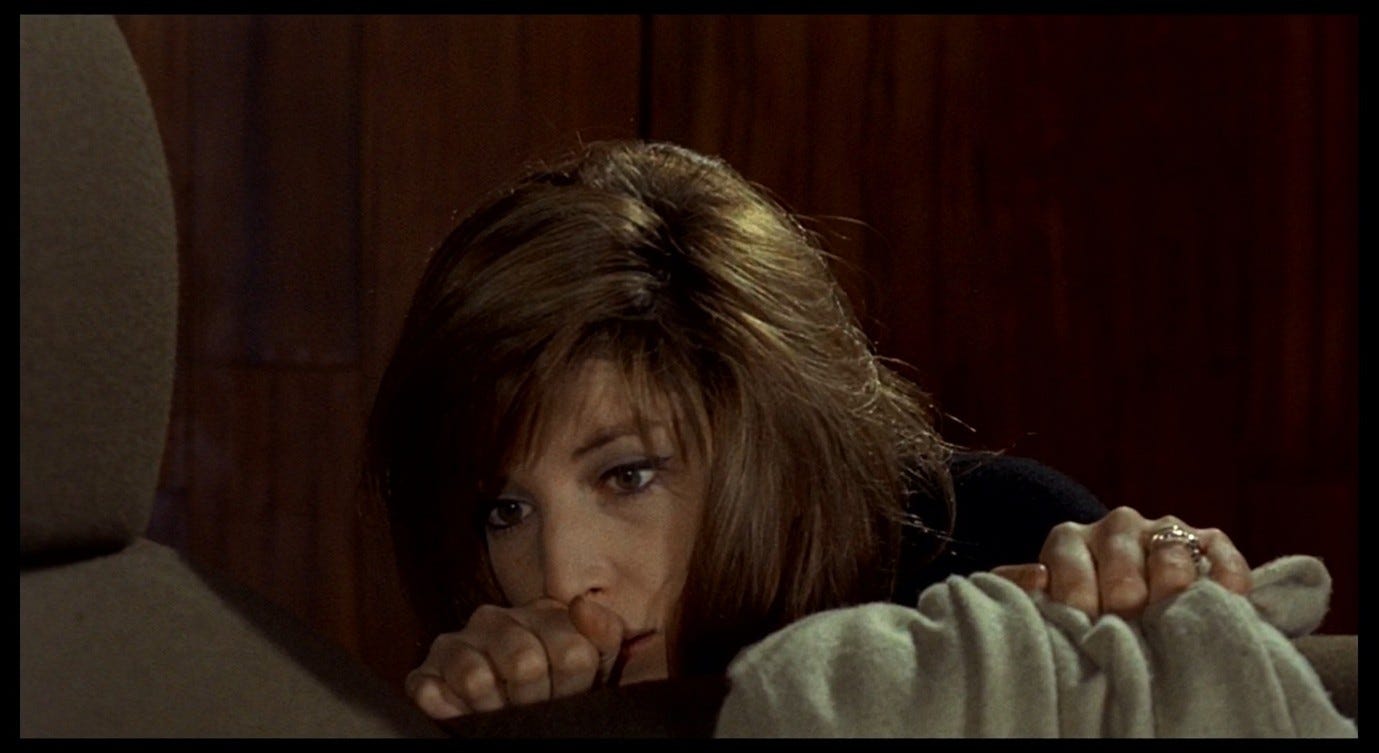

The view of Giuliana as mentally ill is, from one point of view, another normalising force that pigeon-holes her into a stereotypically feminine role, that of the hysteric or neurotic. The woman isolated by madness, left to ruminate on her condition in solitude, is not too far removed from the grieving widow or jilted lover subliminally evoked by the image of Giuliana on her knees. When we see that image, we may instinctively find ourselves framing her in terms of a familiar trope, the desolate female victim laid low by tragedy. When we cut from that image to the close-up of her face, we may still regard her with clinical detachment – as a pathetic madwoman falling to pieces – in spite of how physically close we are to her.

However, the figure of the ‘madwoman’ can serve to critique the structures that have marginalised her. Philip Novak compares Red Desert to The Yellow Wallpaper, arguing that it is centrally concerned with ‘Giuliana’s attempts to negotiate the horrors of, not just her physical, but her social environment,’2 and that the madness or neurosis that infects the film’s imagery is

both symptom of and symbolic response to the ugliness, the oppressiveness, the ruinous logic – the lethal rationality – of the physical setting and social order portrayed.3

As Novak also points out, Antonioni himself did not entirely endorse this view of the film in interviews, tending instead to frame it as a story of someone who fails to adapt to her changing environment:

I’m not against progress. But there are people who, by their nature, by their moral makeup, have to wrestle with the modern world and can’t manage to adapt to it. And thus we witness a sort of process of natural selection: the ones who survive are those who manage to keep up with progress, while the others disappear, swallowed up by their crises. Because progress is inexorable, like revolutions. In the same way that some people suffer during a revolution, there is also a malaise connected to progress. It’s life itself and there is nothing extraordinary about that.4

As usual, the ambiguity of these comments is their most interesting feature. The above paragraph begins with the disclaimer, ‘I’m not against progress,’ because Antonioni knows this film will come across, in some ways, as a critique of progress, and I think his primary intent here is to urge viewers to see the film in more complex terms. In a 1969 interview, Charles Thomas Samuels confronted Antonioni about the tension between his stated intentions in Red Desert and the way the film actually comes across:

SAMUELS: But doesn’t [Red Desert] show that [Giuliana’s] ambiance is, in some sense, the cause of her neurosis?

ANTONIONI: Yes, but nobody becomes neurotic if they haven’t a – I mean, neurosis attaches itself to a fertile ground where it can flourish. There is always a physical basis so that the environment plays its part only to the degree that the physical makeup of the person is susceptible to its influence. It doesn’t interest me to go into the origins of neurosis, only its effects.

SAMUELS: But there are characters in Red Desert who resist their environment and don’t become neurotic. What typifies their makeup and is absent from Giuliana’s?

ANTONIONI: I don’t know, but Giuliana was more important to me than the others because she represents an extreme version of them. […] In her, there is that basis for the environment to work on. Who knows why? Hereditary defects, maternal or paternal? There are a thousand reasons why a person is neurotic. Then one day the neurosis explodes. That explosion is what interests me.5

The crucial detail here is the focus on effects rather than origins, on the explosion rather than its basis. It would be interesting to know why Antonioni was so eager to move on from the topic of causes to that of effects, as soon as the former came up, but that shift is in itself significant. The framing that explains the story (Giuliana cannot adapt to modernity) is gestured towards, the explanation for her illness (she has internal defects that make her allergic to her environment) is rehearsed, but then both are put to one side. We might tell stories like that or see people in those terms, but this is not the business of Red Desert. We are asked to focus on the effects, the symptoms, the slow-motion explosion, and to be open to interpreting them in different ways. Later in the same interview, Antonioni advises Samuels on how he should respond to characters like Giuliana:

ANTONIONI: See them as something that sparks a reaction within you so that they become a personal experience. The critic is a spectator and an artist insofar as he transforms the work into a personal thing of his own.

SAMUELS: What if I transform the film into something wrong?

ANTONIONI: There is nothing in the film beyond what you feel.6

This is a gift to film scholars everywhere, but it is particularly revealing in the context of a discussion about Red Desert, which is so intensely focused on what its protagonist feels. When Antonioni says that progress is inexorable, that some people cannot survive it, and that this is just how life goes, or when he argues that Giuliana has internal defects that make her susceptible to the neurosis-inducing aspects of her environment, it is natural (and not entirely wrong) to see him as adopting a distanced, superior, and perhaps misogynistic stance in relation to the character. But there is nothing in the film, or in his comments about it, beyond what Giuliana feels, and all these comments reflect her feelings. It is Giuliana who senses a revolution taking place around her, who recognises that others do not suffer from it as she does, who calls herself a crettina for having needs that cannot be met by her environment, and who intermittently – and, by the end of the film, with some determination – adopts a philosophical stance about the inescapability of her own condition. The Antonioni who says, ‘It’s life itself and there is nothing extraordinary about that,’ is more or less identical with the Giuliana who says, ‘Everything that happens to me is my life – that’s all.’ We sense that something is wrong with us, though we do not know what it is; all we know is the way it manifests in our perceptions and emotions. This is the Red Desert experience.

Moreover, even if we do not empathise with Giuliana but see her instead from an Ugo-like perspective, and feel frustrated by her failure to cope with reality, the film does not allow us to occupy this perspective comfortably. The close-up on Giuliana as she says, ‘I’ll never be cured,’ is disturbing because it brings us face to face with a woman whose problem is not easy to categorise, and whose emotions are similarly complex.

She is not crying, indeed she never cries throughout the film, and in an earlier scene she berated Linda for crying on her behalf, as if she finds these tears reductive. Giuliana is not simply a bored housewife who needs to find an occupation, nor a sexually unsatisfied housewife who needs the touch of a real man like Corrado. If Antonioni’s camera sometimes appears detached from her experience, and if the film to some extent suggests that her plight is an inevitable by-product of necessary progress, this very tone of pragmatic detachment serves to throw Giuliana’s plight into sharper relief. The apparent coldness of the camera-eye challenges us to recognise this coldness in ourselves. To recognise ourselves in Ugo, Corrado, and the world in which they thrive, cannot be a feel-good experience given how this film plays out. Even if we wholeheartedly embrace that world and its values, Red Desert forces us to see what this costs, and (paradoxically) to see how un-seen this cost is.

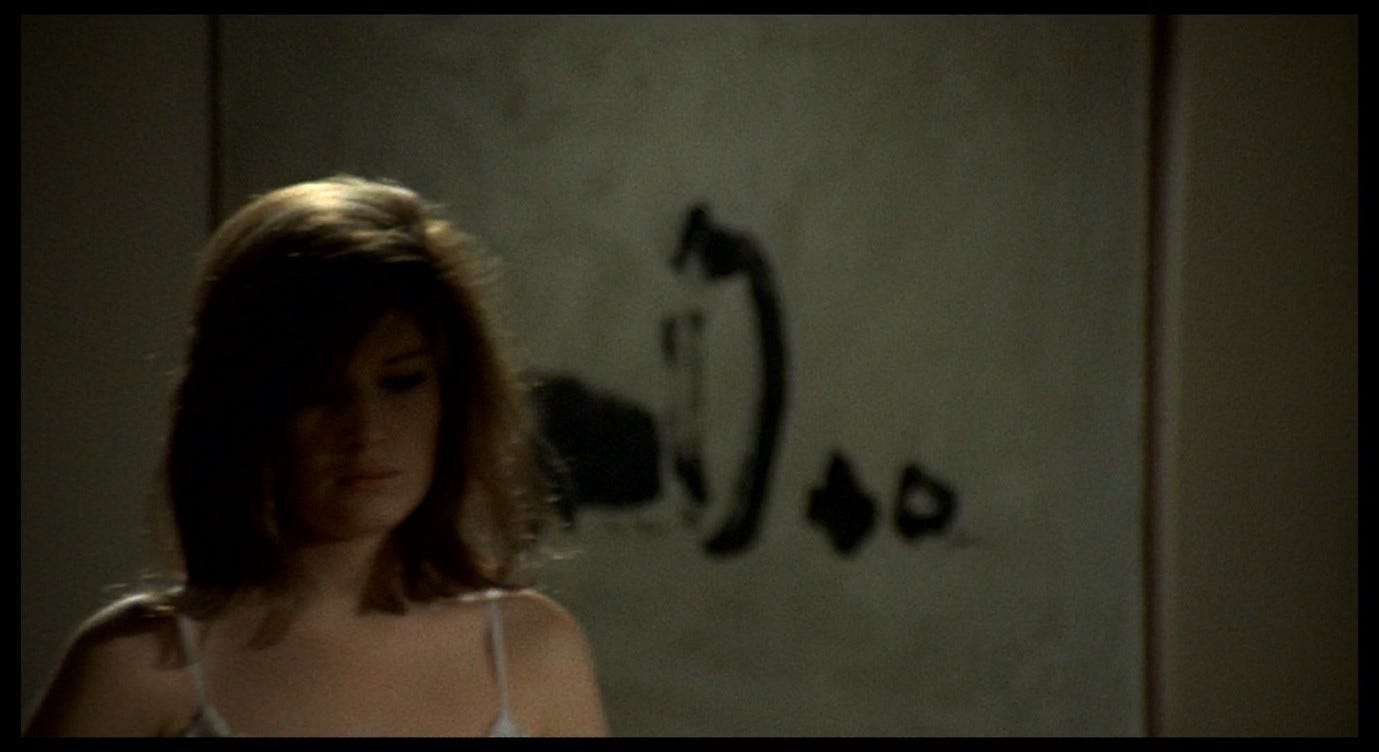

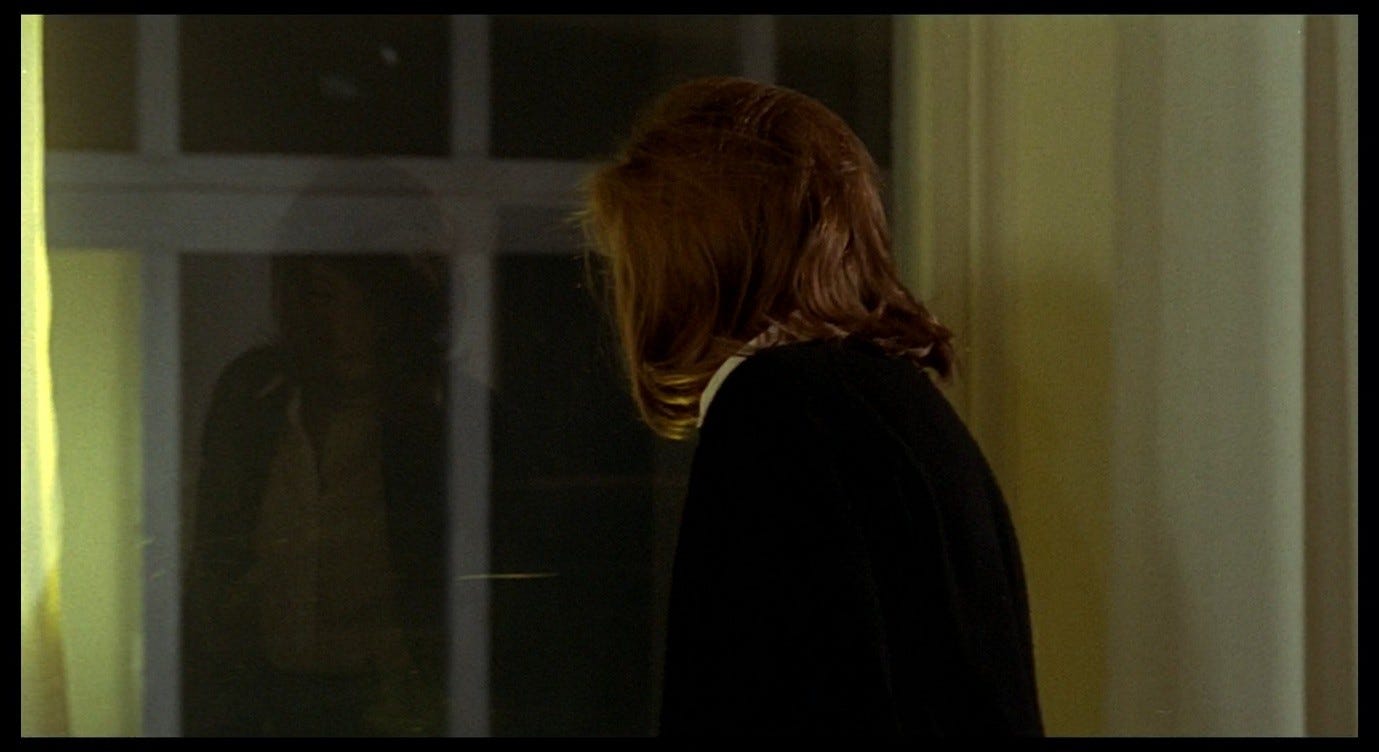

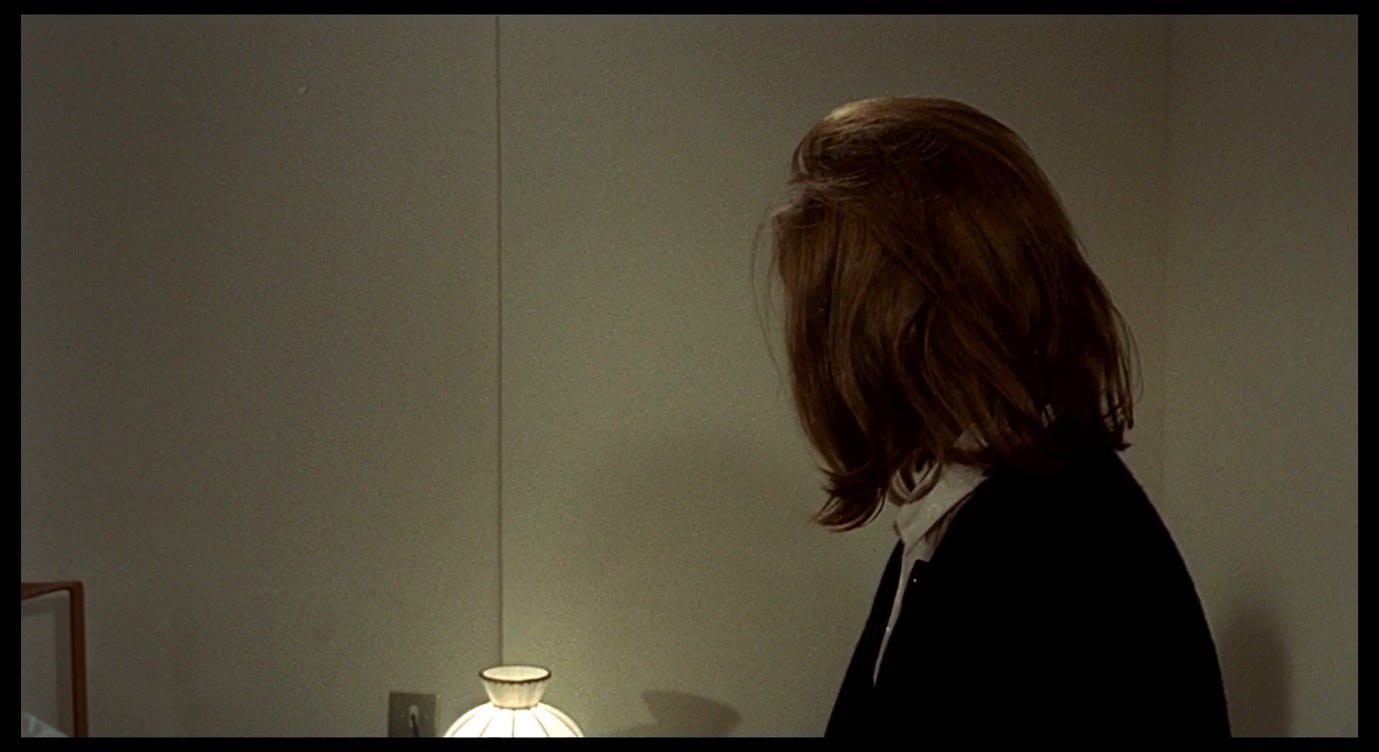

After her brief soliloquy beside the armchair, Giuliana stands up and walks across the room. A yellow light shines through the window.

Earlier on, after she first entered the room, we saw this light blink on, accompanied by a sinister hum.

That hum follows Giuliana now as she steps back into the yellow light and turns to face the camera.

It is another confrontational encounter. She looks at us as though she does not know what she is seeing or what we are seeing, her mouth slightly open as though unsure of what to say to us or of what we might say to her. ‘What should I do with my eyes, how should I look?’ she asked in Max’s shack. What does this image of Giuliana, bathed in a sinister electronic light and haunted by a sinister electronic hum, mean to us, or to her? As in earlier scenes, there is a sense that she is walking across the room to get away from something, and that when she turns to find us staring at her there is something intrusive about our gaze. Among other things, she looks back at us as though she just wants to be left alone. The camera is as insistent and inescapable as the yellow light or the humming noise.

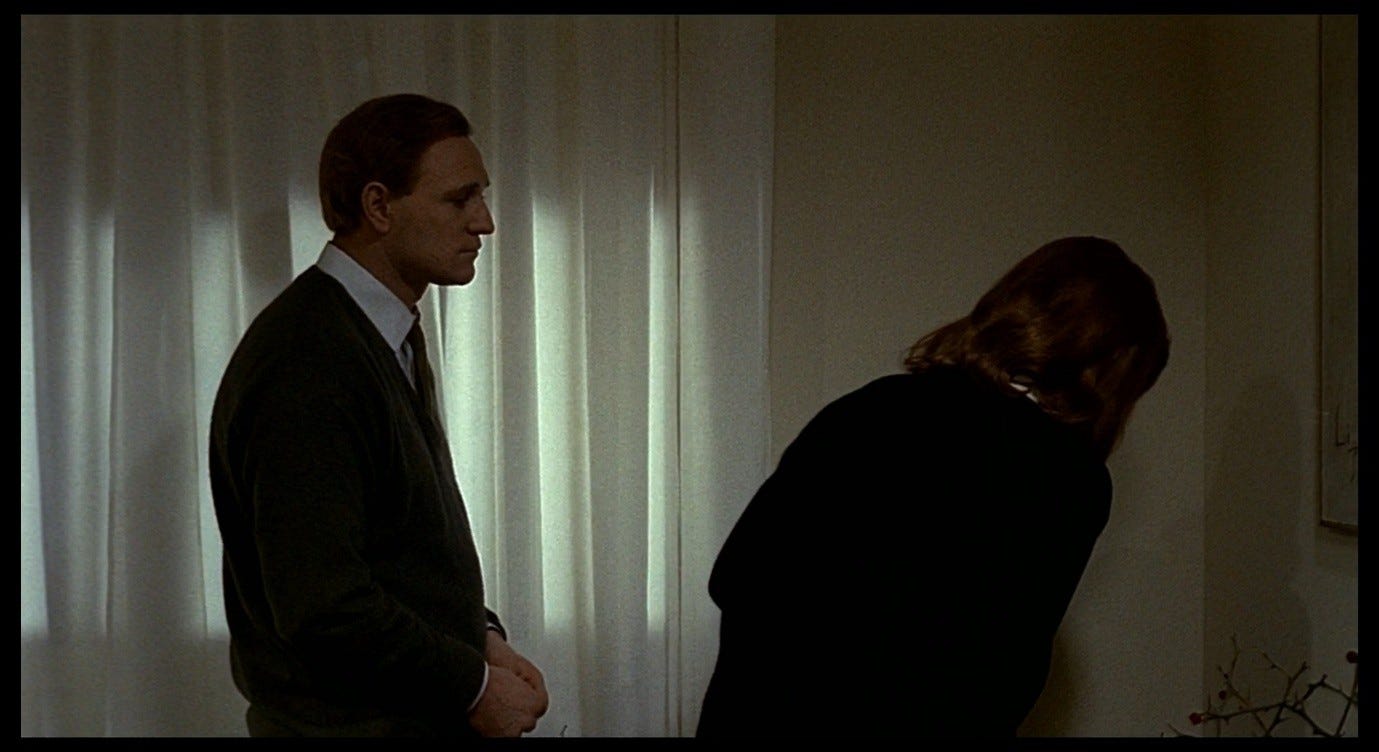

However, the noise stops abruptly as we cut to a different angle. This is another one of those disorienting edits that confuses our sense of the relation between characters. We might have assumed, in the previous shot, that Giuliana was looking at Corrado, and that the camera was occupying his point of view. But when we cut to the reverse-shot, she is positioned to the left of frame and he approaches her from the right. This is a more conventional over-the-shoulder composition, restoring a sense of normality to the scene, but in a way that feels like a violation of the ‘abnormal’ perspective we have grown accustomed to.

Corrado does not face Giuliana head-on, but obliquely; the noise cuts off because he doesn’t hear it; and what he says reinforces his normalising role. ‘You think too much about your illness [malattia],’ he tells her. ‘Instead [invece] it’s an illness like any other. We all have it a little bit, you know. We are all, more or less, in need of a cure [siamo tutti da curare].’ As he speaks the first sentence, he approaches Giuliana rather quickly – he almost seems to lunge at her – and speaks in a rapid, insistent tone. He breaks in upon her morbid reflections to tell her she is over-indulging in them, and that this is the real cause of her illness. She thinks too much about it, so his words and gestures forcibly break that train of thought. After this somewhat aggressive entrance, Corrado speaks gently and complacently.

Giuliana’s illness should not be dwelt upon because it is common, indeed universal, and we are all da curare to some extent. One might think that if everyone has this illness, we need to think about it more, not less, but Corrado is suggesting that it is a fact of life we need to resign ourselves to, not something that can ever be resolved. Giuliana imagines being cured and fears she never will be; Corrado says we are all perpetually da curare and there is nothing to do about this but shrug and carry on. Non sono guarita should be replaced by Siamo da curare, that is, by a relentlessly forward-looking attitude that never dwells on the past or present, and that paradoxically wards off any potential change (or cure) through constant progress.

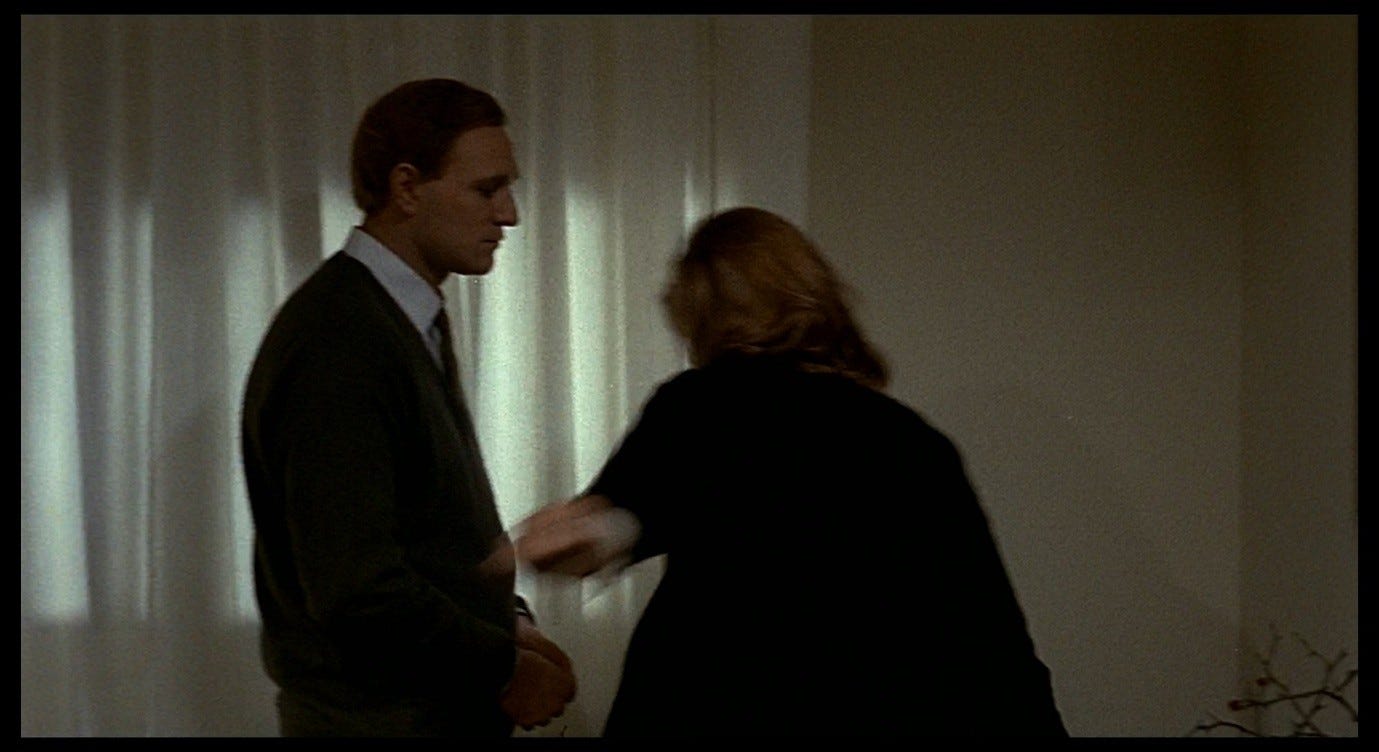

What we see and hear, the way it is edited, and the content of what Corrado says, all combine to show that he does not see or hear Giuliana. Ironically, given what he is saying, he is thinking too much about his own condition and not seeing what is in front of him. The screenplay comments, ‘He tries to smile, but Giuliana does not look at him.’7 Her face remains hidden for this part of the shot. As well as being unseen by him, she chooses not to see him. Just after he says, ‘we all have [this illness] a little bit, you know,’ Giuliana moves from left to right, walking past him as the camera pans with her.

Like her other peregrinations around the room, this movement seems like a way of rejecting one position and searching for another where she might find refuge or comfort. Corrado introduces his explanation of her illness with the word invece, which like ‘instead’ literally means ‘in place’. He wants to move her understanding of her condition from one place to another, and there is something quietly subversive about her own movement away from the position he has put her in. He wants her here; instead, she will be there. Giuliana used the same rhetorical method to make a point on the SAROM rig, moving from one place to another, taking Corrado with her, and illustrating – by the shift in the topic of conversation – how an altered context can re-configure relationships.

In the hotel room, as on the rig, Corrado follows Giuliana. He watches from behind as she examines the chest of drawers in the corner. Then she suddenly turns away from the drawers to move quickly past him, and as she passes he grabs her hand to stop her.

The electronic hum returns at this moment. Does the sound align with her gesture, or with his? Does she turn because she hears this noise, or does she hear this noise because he tries to hold onto her? She slowly withdraws her hand from his and continues across the room, before sitting down in a chair, finally facing in our direction again. She clutches her shirt over her stomach as though suppressing nausea or holding herself together. The space she occupies is brightly (and rather artificially) lit, while Corrado stands in the shadows.

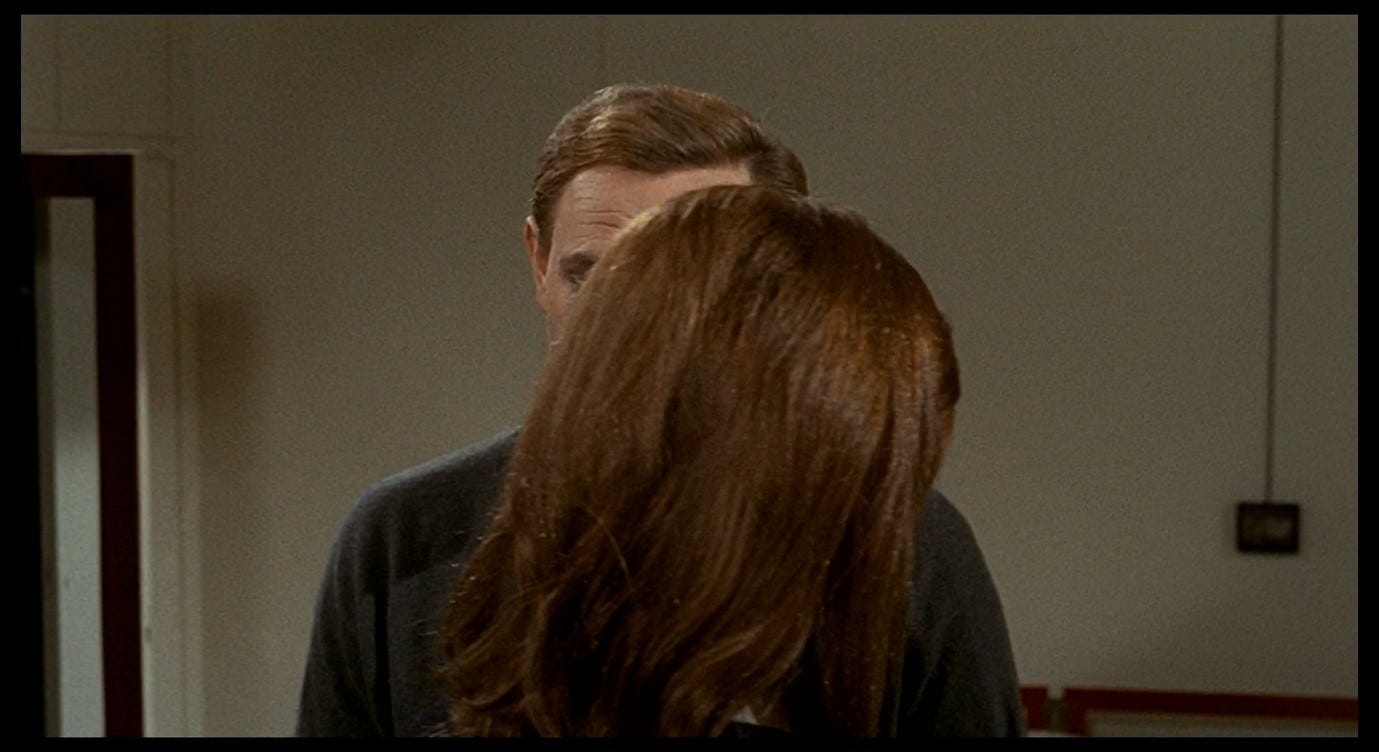

Now the camera aligns itself with Corrado’s movements, panning left as he moves in front of Giuliana, then tilting down as he sits on the bed.

Moments earlier, we went from our face-to-face view of Giuliana to a reverse-shot of Corrado looking at her from an oblique angle. Now, he places himself face to face with her, blocking her from our view: we can only glimpse some of her hair and the halo of light on either side of her head. This time, the effect is to suggest not only that he does not see her, but that he eclipses her. No one – not even the camera – can see her now, and Corrado replaces whatever she was looking at with himself. ‘Forming much more than the wall of loved ones she has asked for,’ says Peter Brunette, ‘he seems to obliterate her completely.’8 His action constitutes a response to and a critique of her wall-of-loved-ones fantasy, as though he were saying, ‘You don’t need a wall around you, you just need me in front of you.’

All this, from ‘You think too much’ to the eclipse, occurs within a single shot. There is a growing sense that Corrado is both pursuing and ignoring Giuliana. She cannot make him see her, but cannot escape him either. For all that his movements and speech appear gentle, the bookends of this shot are imbued with a kind of violence: first when he lunges at her to correct her attitude, and later when he positions himself so as to remove her from the frame. Both gestures respond to Giuliana’s front-facing stare, which we have seen many times throughout the film at moments when she wanted to express herself or connect with someone. Corrado repeatedly breaks that stare.

We cut from the ‘eclipse’ (which faces Giuliana from a 180-degree angle) to a shot of Giuliana from her left side (at a 90-degree angle), momentarily excluding Corrado from the frame. Her face is covered by her hair, and she turns away from us as she goes over to Corrado’s bedside table and picks up his map.

When she looks at the map, she holds it up so that it covers most of her face. When Corrado strokes her hair and massages her head, she turns her face away towards the bed.

As in the previous shot, Giuliana is making herself elusive and continually shifting from one position to another, preventing Corrado from engaging with her in any concerted way. She also, in anticipation of the later scene at the docks, talks about leaving her home: she looks at the map and wonders whether there is a place in the world where one goes to get better [stare meglio]. ‘Perhaps not,’ she says with characteristic pessimism. Giuliana looks at this map in much the same way she looks around the hotel room, searching for a place or a stance that will help her stare meglio, and quickly concluding that the search is futile.

In the screenplay, Corrado’s response is prefaced with a stage direction explaining his motives:

Corrado takes advantage of this remark to try and give the conversation a more casual [disinvolto] tone.9

This is an apt description of his conversational strategy throughout the film, and reveals something important not just about what he will say next, but about what he said a few moments earlier. When he told Giuliana that her illness was not unusual and not worth thinking about, he was not – or at least not entirely – speaking in good faith, but trying to steer this encounter in a more casual direction for self-interested reasons. Similarly, when she says that perhaps there is no place in the world that is especially conducive to wellness, he responds (while stroking her hair):

You’re probably right. You travel around and around [gira e rigira] and then end up finding yourself back where you were. That’s what has happened to me. I don’t feel different from six years ago. But I don’t know whether this prompts me to leave or to stay.

Again, he tries to collapse the distinction between himself, Giuliana, and the rest of the world. Her experience is just like everyone else’s, and like his in particular. We are all da curare, we all have needs – and Corrado in particular has needs. We are all torn between staying put and moving on – and Corrado in particular is unsure whether he will stay or leave. This latter point echoes what he said on the SAROM rig, when he hinted that he might never return to Ravenna after leaving for Patagonia. These comments are part of his seduction technique: ‘I’m sick too, please cure me; and do it quickly because I’ll be shipping out soon.’

In both exchanges, Corrado papers over what Giuliana is trying to say. Her illness is manifestly not a condition shared by everyone else, she does not have the luxury of being da curare (rather, she is un-cured and perhaps incurable), and she cannot afford to be so resigned to the impossibility of finding refuge (even if she admits that ‘perhaps’ there is none to be found). There is a depressing congruence between the nature of Giuliana’s condition and the way Corrado responds to it. She is out of step with her environment and wants to escape from its clutches; he is in step with that same environment and wraps it more tightly around her. Murray Pomerance makes the case for Giuliana, not as someone who has failed to adapt and must be swept aside by natural selection, but as an almost idealised exemplar of a sensitivity that our species is in danger of losing:

Her trouble lies in her lack of fit with the world in which she must live – and thus in her resemblance to anyone, man or woman, who fully senses his or her humanity, animality, and linkage to what is around. […] She is perfectly adjusted to another world altogether, an environment we might describe as being ‘whole’ and ‘unfractured,’ certainly a premodern and pretechnological state of things, existing now, perhaps, only in her dim imagination, where people have not been split apart into functions, where bodies are united, where the outside and the inside are merged, singular, indistinct.10

Corrado is trying to tone down Giuliana’s sensitivity to alleviate her pain, but it is his lack of sensitivity that prevents him from helping her. For her to experience the comfort he offers her in this scene, she would need to be in denial; as it is, she cannot help seeing Corrado, and his behaviour, and her relationship with him, in their true form. Pomerance invokes the theories of R. D. Laing (current at the time of Red Desert’s release) in order to argue that

Giuliana is not really neurotic at all. But she is living in a world that is entirely and utterly hostile to her true interests, a world that makes ‘neurotics’ out of people like her.11

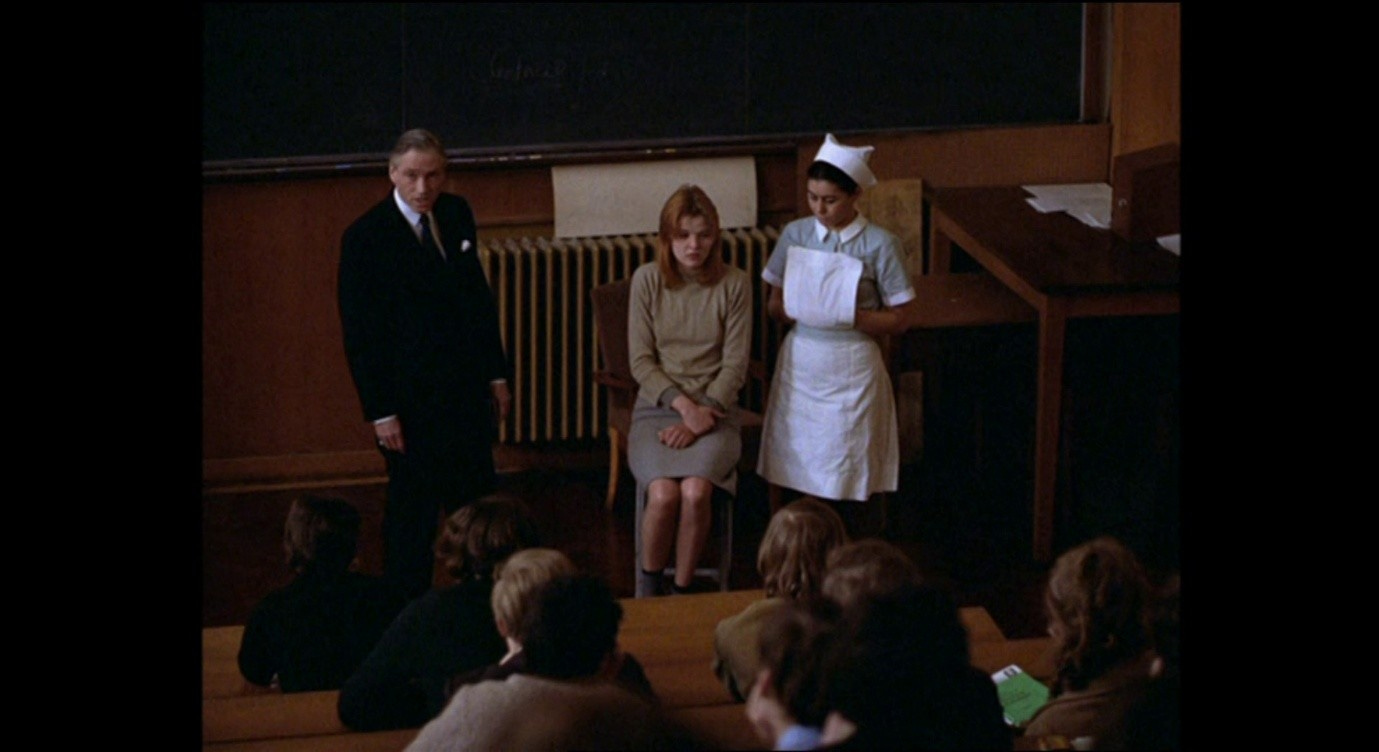

Described like this, Red Desert sounds a lot like Ken Loach’s Family Life, which was heavily influenced by Laing. ‘As far as we know,’ says Janice’s doctor in that film, ‘there’s no discernible link between her various symptoms and her environment.’

It is a moment of extreme dramatic irony, because we have watched Janice’s environment exacerbate her mental illness in real time. During a family argument over the dinner table, Janice’s sister repeatedly confronts her parents with the rhetorical question, ‘Doesn’t it ever occur to you why she’s in this state?’ At other moments she tells them directly, ‘You’ve done this to her.’

The dynamics of passing items across the table and distributing jelly seem as integral to the operation of this brain-poisoning context as the more obviously abusive treatment Janice receives. Even her sister’s children, sitting glumly in the midst of this incomprehensible family row, seem to be taking some subtle form of damage.

Giuliana wanders around Corrado’s hotel room, touching objects, picking up a book, picking up the map, and this apparently aimless fidgeting shows her ‘lack of fit’ (to use Pomerance’s phrase) with her environment, her vague sense that something is ‘off’ in this room and needs to be changed, though no amount fidgeting or rearranging seems to do the trick. In Family Life, Janice shows the same tendency. During an intense conversation with her parents, she points to an object across the room and says, ‘That little thing needs dusting, you know. That china vase thing.’ There is a shocked silence. ‘What did she say?’ asks her father. ‘I think you ought to see a doctor,’ says the mother.

Ostensibly, they are worried by their daughter’s non-sequitur at such a serious moment, but they also feel threatened by the link she is implicitly drawing between her condition and her (metaphorically) dust-covered surroundings. Later, Janice nervously touches a small decorative object during an argument, before turning away from it to say to her mother, ‘Anybody would think you’re inside my head or something!’ ‘Yes well maybe I am,’ replies the mother. ‘You’re more part of me than anyone else in the world.’

Janice looks to her environment for a distraction, an avenue of escape, a space where she can be herself, a place to stare meglio as Giuliana might say. But her environment is not just the literal room she is in, it is also the layers of emotional, cultural, and moral significance infused into every object and every interaction (personal or otherwise) in her home. It is everything contained in the phrase ‘family life’. Unable to sleep one night, Janice tries to carve her name into the living room table, then gives up and drifts around the room holding a clock – which she suddenly smashes on the floor. ‘Time,’ she explains to the doctor and her parents afterwards. ‘I was killing time.’

The clock, given to her father in recognition for long service in his job, stands not so much for the passing of time and the inevitability of change – as it might for Antonioni’s characters – but for the weight of the past, what Antonioni refers to as the vieilles choses (see Part 9) that refuse to die and be buried. The film begins with and often returns to images of identical suburban houses, arranged in seemingly endless rows as far as the eye can see. ‘That’s your mum and dad,’ says Janice’s boyfriend. ‘And that’s normal. But is it sane? Do you think it’s sane?’

This is the central question of Family Life, and again it is a rhetorical one. We know that Janice is ‘insane’ only insofar as she is driven insane by her truly insane environment. Her parents tell her she must cooperate with the doctors or she might be stuck in the hospital forever. With chilling conviction, Janice retorts: ‘You know sometimes I think it’s if I do cooperate that’s how I’ll be in here forever.’

This line has two meanings. On the one hand, Janice senses that her parents and the doctors want her to be insane, to be the madwoman they think she is, because this is preferable to seeing their world – the household, the institutions they have built – challenged. On the other hand, she also senses that if she ‘recovers’ and behaves in accordance with their definition of sanity, she will truly ‘be in here forever,’ even if she is discharged from the hospital and builds a life for herself in that world of identical houses. ‘Here’ does not just mean the hospital, it means this whole plane of reality where all Janice’s feelings, her entire sense of herself, have to be constantly repressed. This key moment in Family Life is like the one in Red Desert when Giuliana says, ‘I haven’t been cured, I’ll never be cured, never, never…’ Most obviously, this is an expression of despair. But it is also a kind of defiant protest. Who in their right mind would want to be cured of seeing their environment for what it is?

Next: Part 39, What is Giuliana afraid of?

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Elwell, Frederick, The Wedding Dress (1911), Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston Upon Hull; image taken from ArtUK.org

Novak, Philip, Interpretation and Film Studies (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p. 82

Novak, Philip, Interpretation and Film Studies (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p. 81

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; p. 285

Samuels, Charles Thomas, ‘Michelangelo Antonioni’ (29 July 1969), in Encountering Directors (New York: Capricorn Books, 1972), pp. 15-32; pp. 29-30. Also available via Scraps From the Loft.

Samuels, Charles Thomas, ‘Michelangelo Antonioni’ (29 July 1969), in Encountering Directors (New York: Capricorn Books, 1972), pp. 15-32; pp. 21-22. Also available via Scraps From the Loft.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 491

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 104

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 491

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp. 72-73, 91

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 92