Everything That Happens in Red Desert (45)

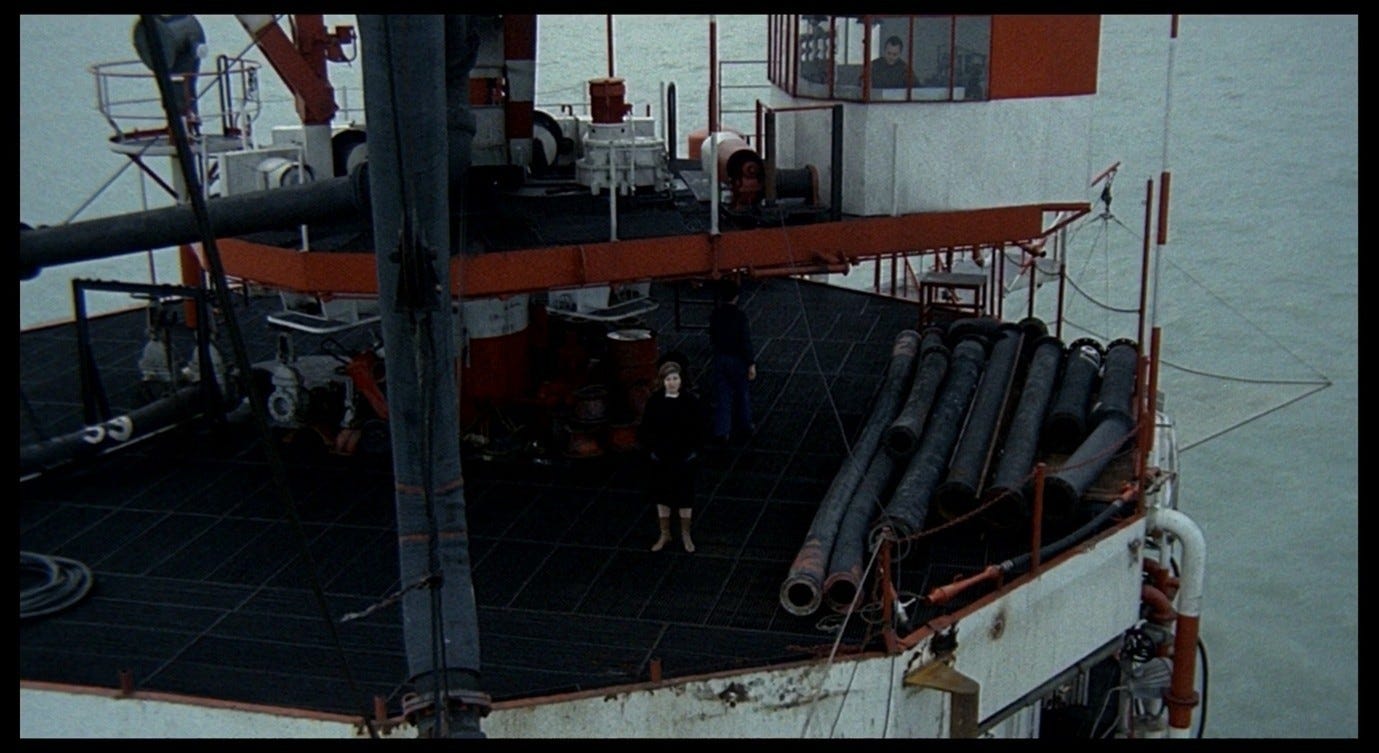

The harbour

This post contains some brief discussion of suicide.

Towards the end of filming, Red Desert was thrown into crisis by the sudden departure of Richard Harris. Antonioni describes how he dealt with this problem:

The ending was supposed to be all three of them – the wife, the husband, and the third man. So I didn’t know how to finish the film. I didn’t stop working during the day, but at night I would walk around the harbor thinking until I finally came up with the idea for the ending I have now. Which I think was better than the previous one – fortunately.1

The result is a sequence in which Giuliana herself, thrown into crisis by her recent interactions with Valerio and Corrado, wanders around the port of Ravenna looking for the right ending to her story. What happens when she finds herself alone, without any source of help or comfort, forced to fall back on her own resources? The film-maker’s creative impasse blurs into Giuliana’s existential breakdown. Like many of the best sequences in Antonioni’s films, this one is born out of the material circumstances in which it was shot, while also transforming a real-life location into a landscape of the mind. It is the strangest climactic scene in Antonioni’s filmography – more like an interlude than a climax – but its tone of muted lassitude is appropriate to the hauntingly inadequate conclusions Giuliana will arrive at. The violence of the un-filmed paint-flinging confrontation between Giuliana, Ugo, and Corrado (discussed in Part 42) might have been more dramatic, but what we have instead gains its unique power from its sense of bathos.

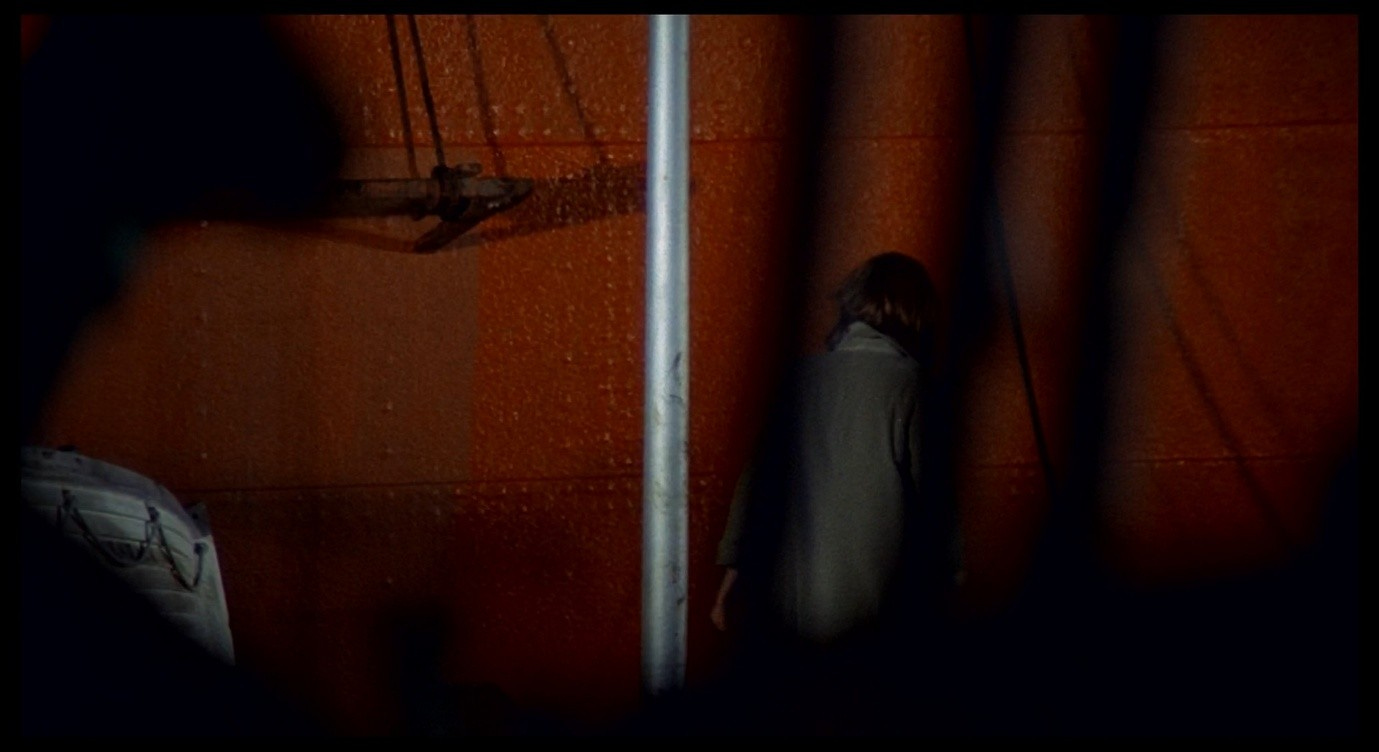

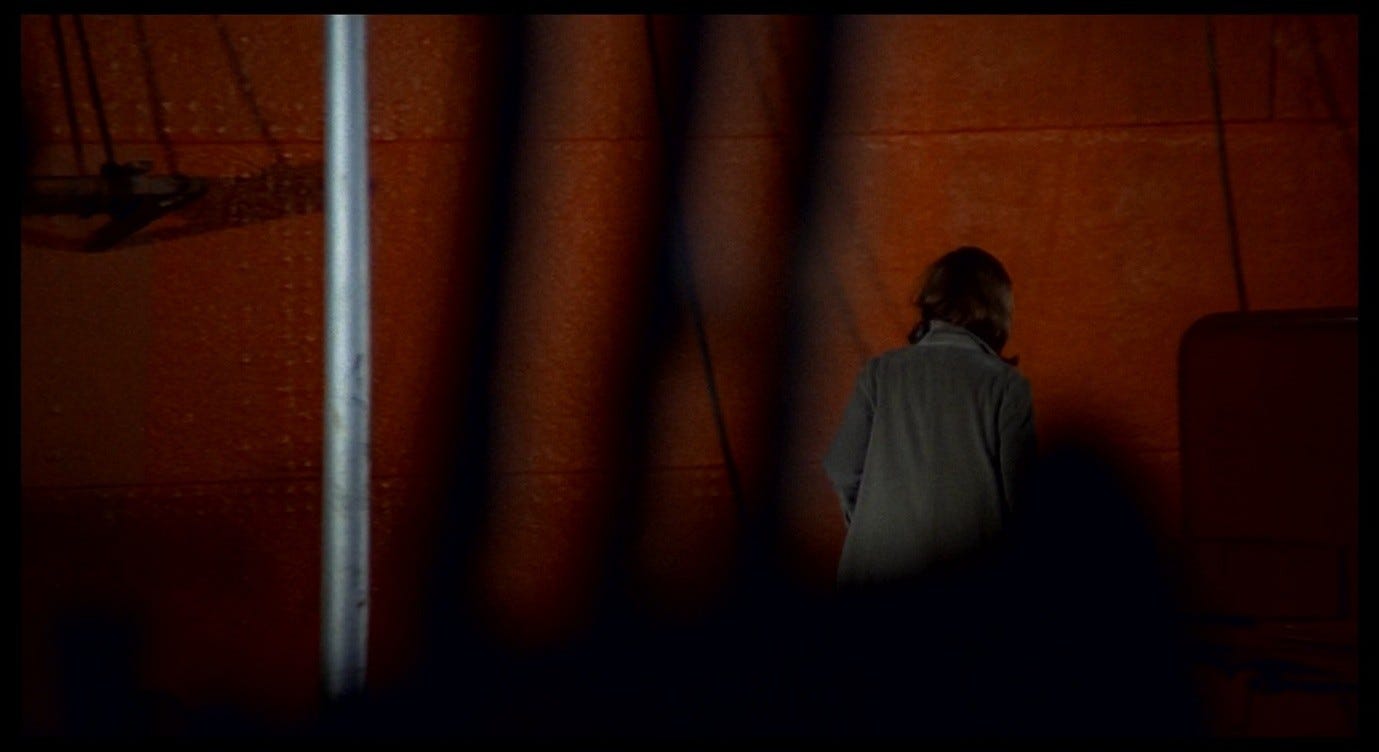

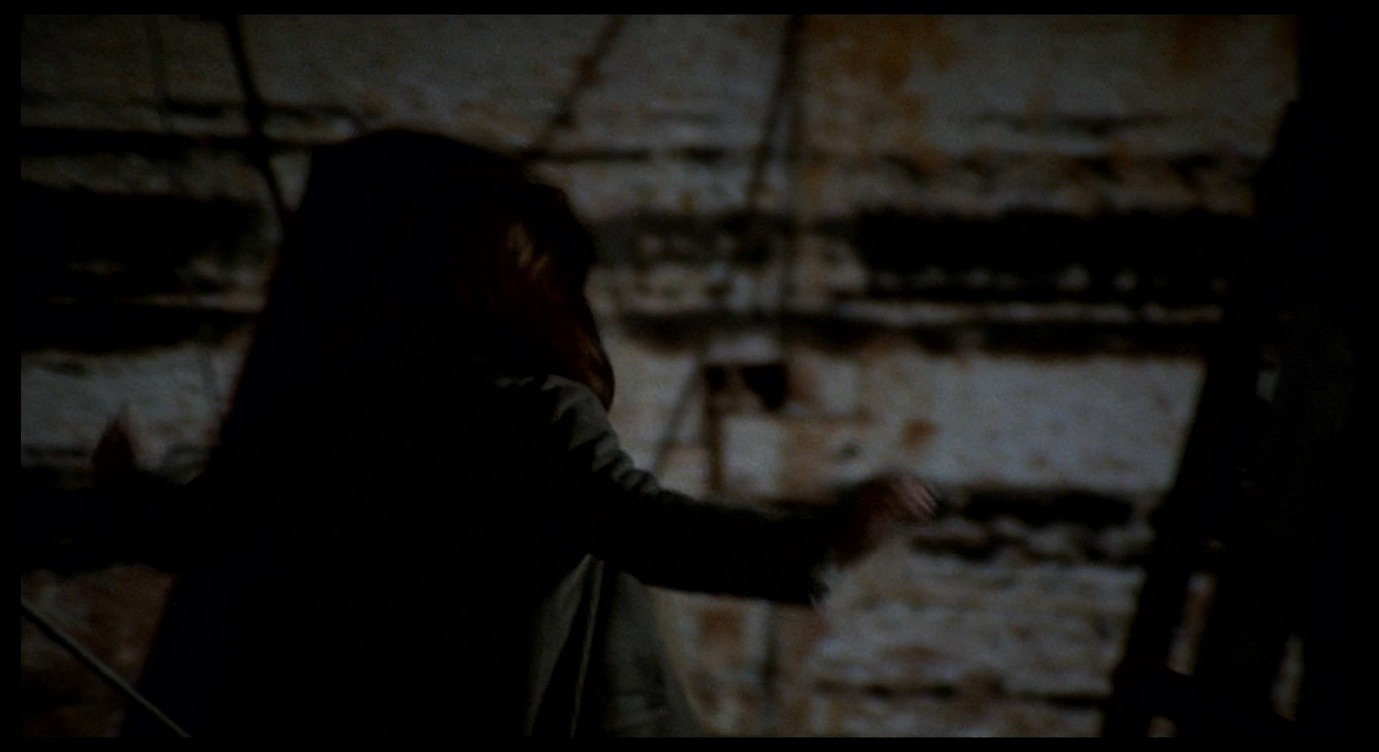

The first part of this sequence is structured around a familiar pattern: disorienting long-lens shots followed by wide-angle shots that give us a clearer impression of the setting. First, we cut from the grey segment of the Via Alighieri (which has just been vacated by Corrado) to a red surface that fills the frame and seems (thanks to the telephoto lens) much closer to us.

We see red metal squares joined together to form a wall. Set against this red wall are lines patterned in threes: three vertical objects (two ropes and a metal bar) extend downwards close to the wall; each of the ropes appears tripled because of the two shadows it casts; in the foreground, so out of focus they look like shadows, are three wavy lines. Some of these lines seem to blur into each other, or to be on the verge of aligning with or complementing each other. It is like an eye-test that requires us to bring a set of objects into alignment and into focus – but an eye-test that we are failing. As usual with the establishing shots in Red Desert, we cannot immediately be sure of where we are, and in this case the blurring and tripling of objects within the frame compounds our disorientation.

The camera tilts down, following the vertical lines. The rope on the left is multiplied again by a pulley mechanism, then comes to a stop at the cleat to which it is fastened, while the other rope continues to extend below the frame.

The three wavy lines straighten out and run in parallel with each other, crossing the right-hand side of the image at an angle. The metal bar at the centre leans slightly to the right, but is almost perpendicular to the upper and lower boundaries of the image. This bar is like a standard to which the three lines on the right are trying, but failing, to conform. However, the disorder of the initial image is mitigated. The lines that break up the space are guiding our eyes downwards and becoming simpler as they do so.

This one camera-tilt serves to ‘explain’ the setting, even before we cut to the more legible wide shot. When we see the cleat, we realise that the ropes are attached to a ship; when the camera comes to a stop, we see an upturned lifeboat on the left-hand side of the frame; and the three out-of-focus lines connect with an object at the bottom of the frame that extends to the left. The lifeboat and the obscure object in the foreground let us know that we are now ‘grounded’ on the docks, looking from an eye-level perspective, and we have a long moment in which to register this before Giuliana enters the frame.

The screenplay describes Giuliana’s journey through the shipyard in the following terms:

By the way she walks, it is clear that Giuliana (despite the terror which the huge shadows of the hulks arouse in her) still pursues her intention. She proceeds cautiously, with the amazement of discovering at first-hand a world not previously explored. She is afraid, but the state of crisis in which she finds herself gives her the courage to carry on.2

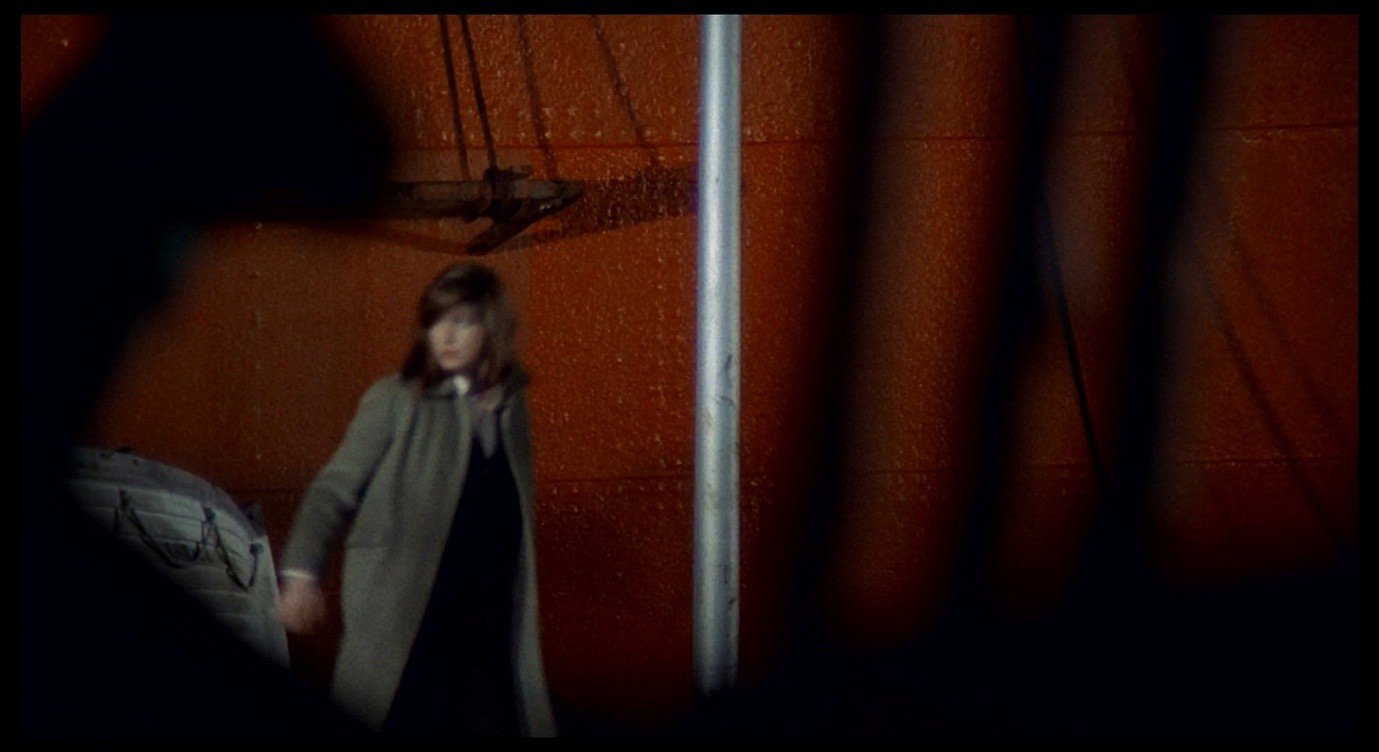

The terror described at the start of this passage is evoked by the opening shot of the sequence, which begins by looking upwards and then tilts down to measure the scale of the ship’s hull. When Giuliana does appear, she seems noticeably small and vulnerable in this setting.

This too is a familiar pattern by now. In the film’s opening sequence, outside the factory, the camera began at an impossible height with the fire-spewing flare-stack, then travelled down to human level through a series of cuts and pans.

We first saw the SAROM island from a great distance, then came in closer to find Giuliana exploring the intricacies of this metal structure planted in the ocean.

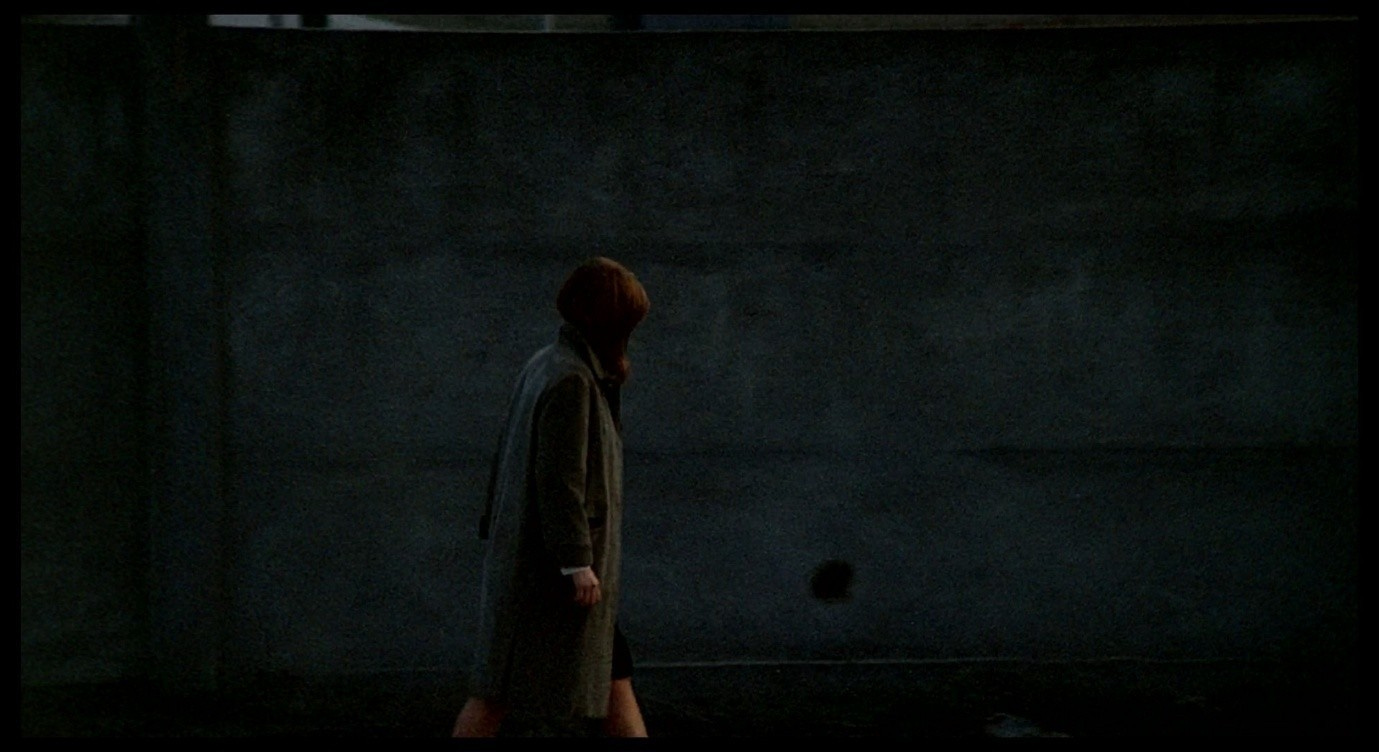

Just before the hotel room sequence, we saw Giuliana walking against a grey wall, then we pulled back to find her dwarfed not only by the wall but also by the cluster of industrial orbs behind it.

In the harbour, more than ever before, we sense that Giuliana has travelled into the depths of a menacing alien environment. A feeling of depth is created by that initial downwards tilt: the hulk towers above us, filling up so much space that we cannot see it all in one go, and we are down here in the lower depths, among the clutter and detritus. When Giuliana arrives, we cannot see the ground she walks on, so she seems to be wading through this detritus. The towering hulk itself is overwhelmingly red, for reasons I will come back to later, but in the context of Giuliana’s state of crisis it strikes a tone of alarm and danger.

After the silence that followed Corrado’s disappearing footsteps in the previous shot, a noise breaks into the soundtrack as we cut to the docklands: a jarring, high-pitched metallic echo. We seem to have arrived in the middle of this echo. Beneath it is an oscillating shimmer, like sheet metal rippling as it falls to the ground. These are the songs of the machines, of hulks swaying slowly in the water and scraping against each other, communicating in their specialised language, or perhaps just expressing themselves – the sounds are not unlike cries of anguish. We are in a world that consists entirely of rusty, clanging mechanical structures, and for a long time we see no sign of human life at all. Whereas the SAROM rig, despite its isolated position, was visibly designed to be traversed and operated by human engineers, the harbour is a much less human-friendly place, an all-metal world that is accessible only to metallic entities.

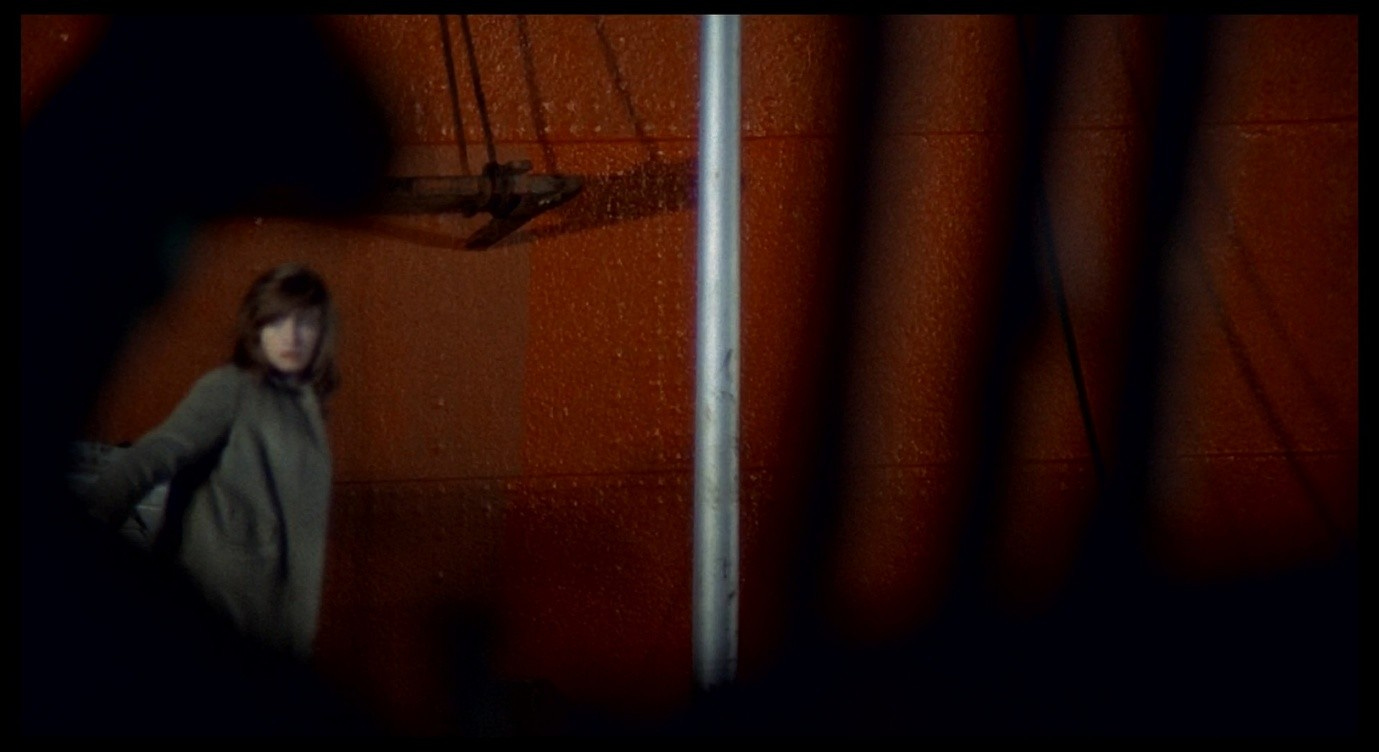

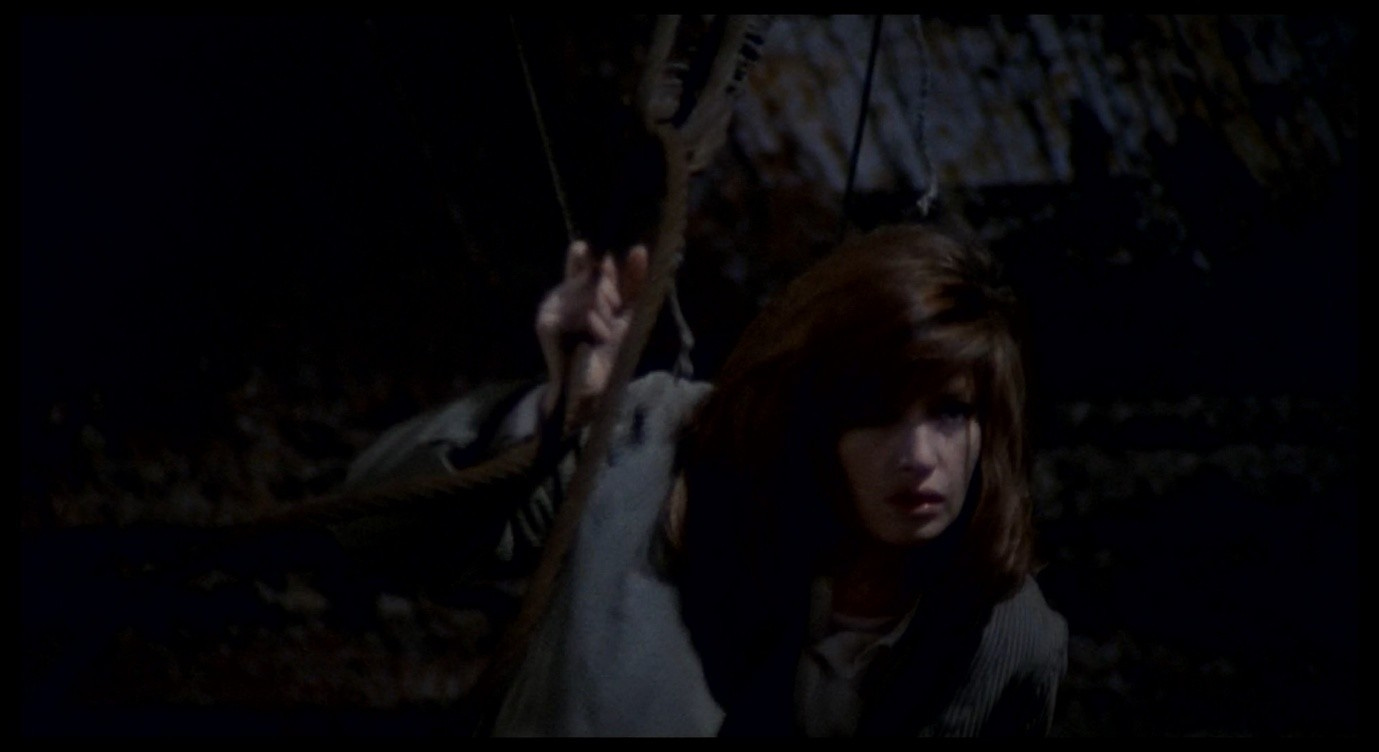

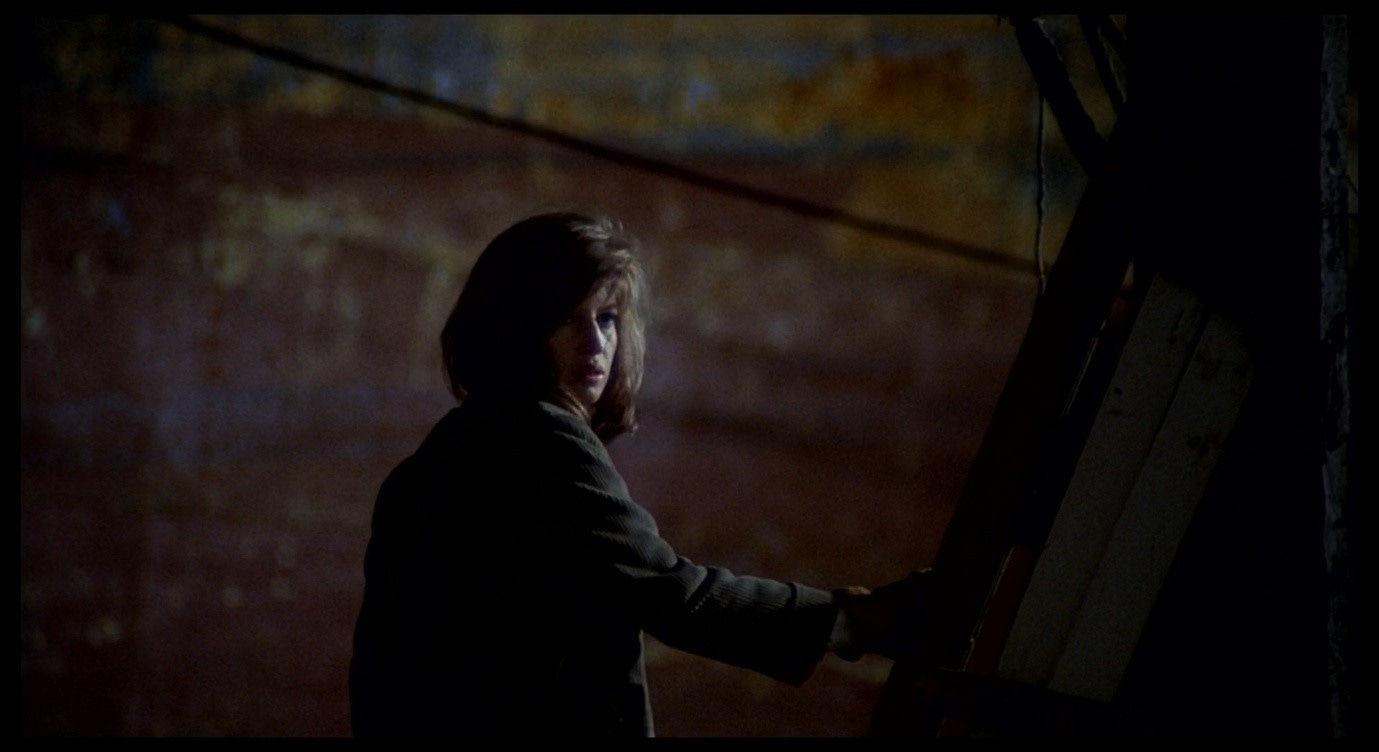

Giuliana’s entrance is typically anxious. As soon as she finds her way into the shot, she glances behind her, something she will do several more times in this sequence, as though she worries that someone or something is following her.

She walks carefully, stumbling a little, the camera panning right to follow her, until she stops short when her way is blocked by a red trailer. She edges around it, glancing down with alarm when she steps on something that makes a noise.

Later, we will see oil spots on the back of her beige coat, and throughout this sequence there is a constant tension as to the physical effect this environment might have on her, strewn as it is with sharp, rusty objects. As the screenplay indicates, Giuliana seems torn between fearing this place and wanting to delve deeper into it. Giuliana is facing her fears, seeking out that ‘terrible thing in reality’ that Corrado refused to acknowledge. In place of his silence we now hear unearthly noise, and in place of his grey stability we see volatile reds and chaotic shapes. This scene is the culmination of Red-Desert-as-horror-film, with Giuliana left alone to face the monster one last time.

As she manoeuvres around the trailer, we cut to a wide shot and see the setting much more clearly.

The object in the foreground remains out of focus and (for me) unidentifiable, but we can see that it is a rusted network of pipes that must at one time have supported the internal workings of a ship. The shipyard is also a makeshift scrapyard where machines go to die, like the blackened slag-heap outside Ugo’s factory or the grey leftovers in the Via Alighieri. We see mechanical innards torn out and discarded and hear a renewed chorus of robotic roaring, as though the local (unseen) beasts were watching Giuliana intrude on their territory. As she disappears momentarily behind the red trailer, we feel again how dangerous it is for her to be here, how easily she could lose herself.

The way she is framed by the metal pipes in the foreground, as she approaches the red trailer, recalls the framing effect of the metallic structure on the SAROM rig. In Part 25, I drew a comparison with Vittoria’s ‘re-framing’ gestures at the start of L’eclisse, and noted that whereas she treats the world like a work of art, the world of Red Desert treats Giuliana like a piece of equipment to be contained and manipulated. Antonioni’s cold-eyed camera, in turn, makes art out of that process.

This time, the framing object is rusty and decayed, and we feel (as Giuliana did when she stared at the slag-heap) the danger of becoming a discarded object, left behind with the rest of the scrap.

The noises on the soundtrack seem more and more like the howls of the damned, a robotic variation on ‘wailing and gnashing of teeth.’ Roberto Calabretto points out the complex layering of diegetic and non-diegetic sound here:

[Vittorio] Gelmetti’s music is blended with port sounds – metallic clangs, sirens and deep rumbles redolent of caves. Thus we have a contrast between what these noises evoke – a working environment – and the nocturnal stillness which blankets the scene. At a certain point, hearing a loud metallic noise, Giuliana turns, seeking its source, only to find that the noise was a product of her angst.3

Elsewhere, Calabretto quotes Gelmetti’s description of his Red Desert score as ‘electronic compositions with the continuous sound presence of machine noises,’4 and in the present scene (unlike in the title sequence) I think these two categories of sound become truly indistinguishable. The ‘working environment’ is not only contrasted with the ‘nocturnal stillness,’ the two are inseparable. Even at night, when almost no one is working in the harbour, the absence of work is expressed through the echoes of work; this is how industry sounds when it sleeps. Interpreted in this way, the soundscape represents a kind of nemesis to Giuliana, as it has done in many earlier scenes. She seeks a place of calm and quiet, but the machine-roars continue to plague her. Alternatively, rather than seeing Giuliana as being in a purely antagonistic relationship with the industrial world, we might see her as being uniquely sensitive to it, attuned to these echoing manifestations of robotic emotion that go unheard by other people. In the harbour, we feel more keenly than ever the agonies of the machine-world, and perhaps detect a kinship between Giuliana and this neglected dimension of industrial Ravenna.

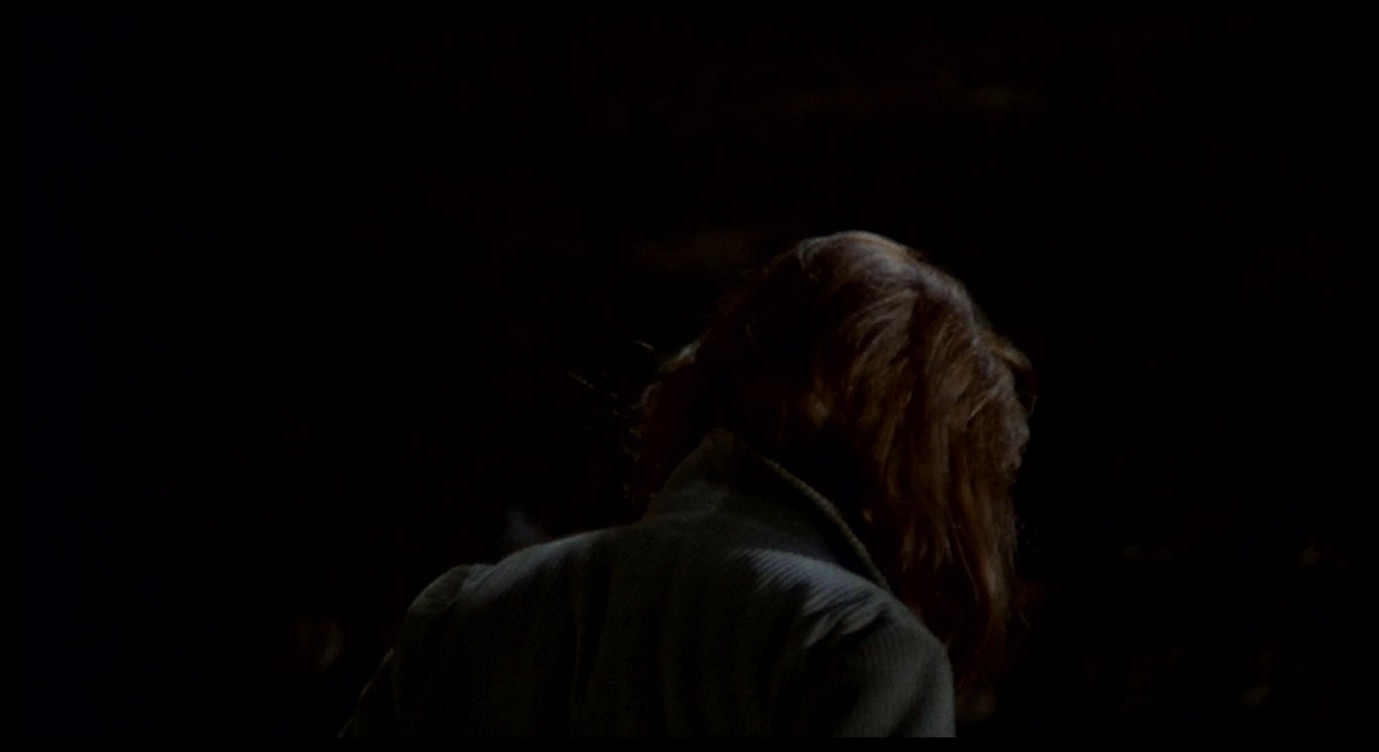

This kinship is suggested not only by her ‘framing’ within that rusty mechanism, but also by the persistence with which she travels through this forbidding landscape, and by the direction she seems to be taking. In the next sequence of shots, we see Giuliana pass beyond the red-painted hull into a darker environment.

The red background is replaced by sections of black-white-and-brown metal that show stratified layers of erosion. Later, when we see the ship from a distance, we see that it has been re-painted (in red) up to a clearly demarcated point.

It is an extraordinary image of a vast machine that is being restored but also transformed. Its old, traumatised self is being painted over and thereby erased, but a section of that old self still remains. The screenplay specifies that the repaired part of the hull is the colour of minium, or red lead, an oxide used in anti-fouling paints that helps to prevent corrosion on ships’ hulls.5 As well as being a colour associated with danger and alarm, red is therefore (in this case) indicative of strength and resilience. However, the progression in these images is from the resilient minium-red towards the darker, more decayed part of the hull. As the image darkens, we become more aware of this as a night-time scene, but also of Giuliana as someone who is deliberately seeking out this marginal, nocturnal realm.

Indeed, one thing that sets this scene apart from the rest of the film is the degree of agency shown by Giuliana. Most of the time we see her reacting to things, tagging along on other people’s journeys, and then sometimes trying to escape from them. This time, she has chosen not to go home or to any other safe, familiar location, but to travel into the almost-deserted docklands alone, at night. She apparently has a specific purpose in mind. After walking a little farther, she pauses and looks down into the water.

It is a gruesome sight, even worse than the polluted pond at the fishing-spot. The water is opaque with a toxic green colour, and there is a thick conglomeration of sludge floating at the edge, light gleaming off it in a silvery shimmer as the water ripples. The glistening sludge almost seems to blend into the stone bulwark that marks the boundary between land and water, as if the one were disintegrating and flowing into the other.

Giuliana’s determination in reaching this point might make us wonder whether she intends to take her own life. Will this be like Mae’s attempted suicide in The Docks of New York, which we see obliquely through an image of her reflection in the water, then of the absence of that reflection after she jumps, then of the ripples caused by her off-screen plunge?

But this is not Giuliana’s intention. The image of the swampy dock-water is not a harbinger of suicide, but a reiteration of a visual motif that runs all the way through this film. If Antonioni and his characters are frequently drawn towards desert spaces, seemingly in the hope of finding solace or connection, Giuliana finds herself drawn towards deserted spaces, towards the slag-heaps, polluted pools, and sludge-filled ports of her world. This is not only the desert where there are few oases left, it is the red desert, full of the still-bleeding flesh of those who died building it, or who live on to keep it intact (see Part 6). In the black sludge that floats on the water, there are two small pieces of wood, recalling the scrap of wood that floats in the water-barrel in the final scenes of L’eclisse. In that case, like the discarded match-book that floats beside it, the piece of wood becomes a weirdly poignant aspect of the ‘eclipse’ mosaic that comes together at the end of that film. The very insignificance of these objects, and the insignificance of the barrel they float in (which leaks out into the ground without anyone noticing), is what lends them such profundity.

The people we see in that sequence do not ‘matter’ either: they are marginal to the film, irrelevant strangers who should not be there; the main characters, who should be there, are pushed out of the film entirely and rendered even more irrelevant. What does the eclipse consist in, what is being eclipsed, and what does it mean to be eclipsed? What does it mean to find oneself in the darkness that lies outside that annihilating light in the final shot, or in the darkness that replaces it when it fades out?

The red desert is a variation on that eclipse, as is the blown-up image in Blow-Up – the object that no longer means anything and that no one cares about, but that also somehow contains a terrible significance.

In Antonioni’s story ‘The event horizon’, a man inspects the wreckage of a crashed plane that had been carrying six wealthy passengers. The sight of this high-class debris triggers a memory:

Once a street-cleaner [spazzino] explained to him how to distinguish the garbage [spazzatura] of poor neighbourhoods from that of the residential quarters. Silver paper on boxes of chocolate, pineapple parings, wilted gardenias, labels from bottles of San Gemini water and French cognac, cabbage leaves… Nothing of all this in the garbage of the poor. The poor eat the cabbage leaves.6

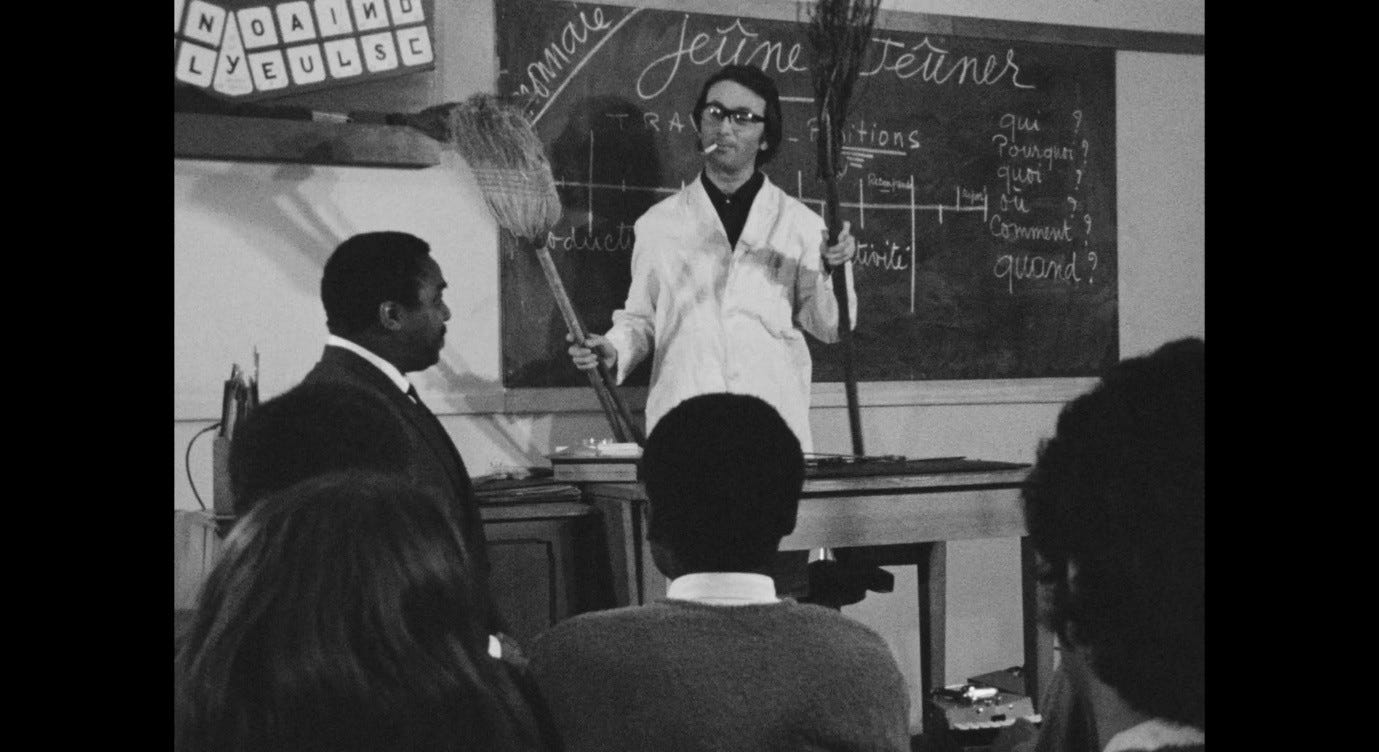

The Italian words for ‘street-cleaner’ and ‘garbage’ are both derived from the verb spazzare, ‘to sweep’. The spazzino is related to the spazzatura as the sweeper is to the sweepings. Like the immigrants in Soleil Ô, who are rigorously taught the French word balai (broom), these are people defined by their attachment to marginal, discarded objects.

The have-nots are defined by an absence (‘nothing of all this’), or by the cabbage leaves they retain and internalise, while the haves are defined by what they throw away, by what appears on the margins of their lives. The poignant implication, in ‘The event horizon’, is that even the rich end up as garbage, their fragmented corpses strewn among their prized possessions on the hill their plane crashed into.

A similar sense of irony informs Antonioni’s documentary N.U., which, as Sam Rohdie says, draws attention to

[the] unreality, almost non-existence of the streetcleaners. The cleaners have no presence for the passers-by in the streets. No one looks at them. No one talks to them. They silently sweep the street, empty dustbins in bare dawn landscapes as if they are more objects than persons, inanimate shades. […] There are scenes of a sweeper looking at his own reflection in a shop window before which he pauses. The reflection looks back at him; both are cut through by another movement and other figures as if sweeper and reflection were not there.7

As we watch this film, however, our attention is almost entirely focused on those unseen ‘inanimate shades,’ while the passers-by who ignore them are left in the margins. Karl Schoonover argues that

[N.U.] focuses on trash and its collectors as a means of retraining our vision along these lines: to see this foreignness in the everyday, to look beyond what we have assumed are the direct forces guiding our lives. What is at stake is the visibility of waste management. This doesn’t just mean showing the garbage itself. It also means exposing our visual, ideological relationship to the world.8

Garbage thus becomes more than just ‘waste to be managed’ – i.e. managed out of sight and out of mind, out of the controlled and regulated spaces of modern life. It comes to represent the foreign, the un-regulated, the un-controlled. The spazzini and the spazzatura they collect are everyday components of our world, and yet – the documentary tells us – we act as though they did not exist. What does that say about our ideological relationship to the world? N.U. does not seem intended to make our hearts bleed for these disenfranchised persons. Rather, like Tanino in the Via Alighieri, it wants to unsettle us. The problem is not that the way we see the world is unethical, but that it is deluded: we are ignoring something in reality.

Giuliana’s urge – which has previously expressed itself through two suicide attempts – to remove herself from the picture, to de-insert herself from reality, is part of what drives her in the present sequence. When she looks into the polluted water, she is like the street-sweeper looking in the shop window, regarding the nebulousness of that reflection and the way in which it is obliterated by competing bodies.

The bits of wood in the sludge are both unimportant and important, in the same way that Giuliana herself is both unimportant and important. In the background of certain shots, we see rippling reflections from the water cast against the ships’ hulls.

Like the watery undulations of the desert in which Walter Faber refused to see any deeper significance, or the floating sludge that looks both pitch-black and luminously silver, this visual disturbance in the fabric of reality is completely trivial but also integral to Giuliana’s state of crisis. Do not look at the ships, this scene tells us: look at the signs of erosion and the reflected light on their hulls, at the waste-products in the water they are swimming in, and at the other kinds of garbage – the innards of old ships, like body-parts left by a plane crash – strewn over the surrounding area. Giuliana’s ‘problem’ is that she has retrained her vision and become attuned to these things, so that she now inhabits a very different space from the one most people would see.

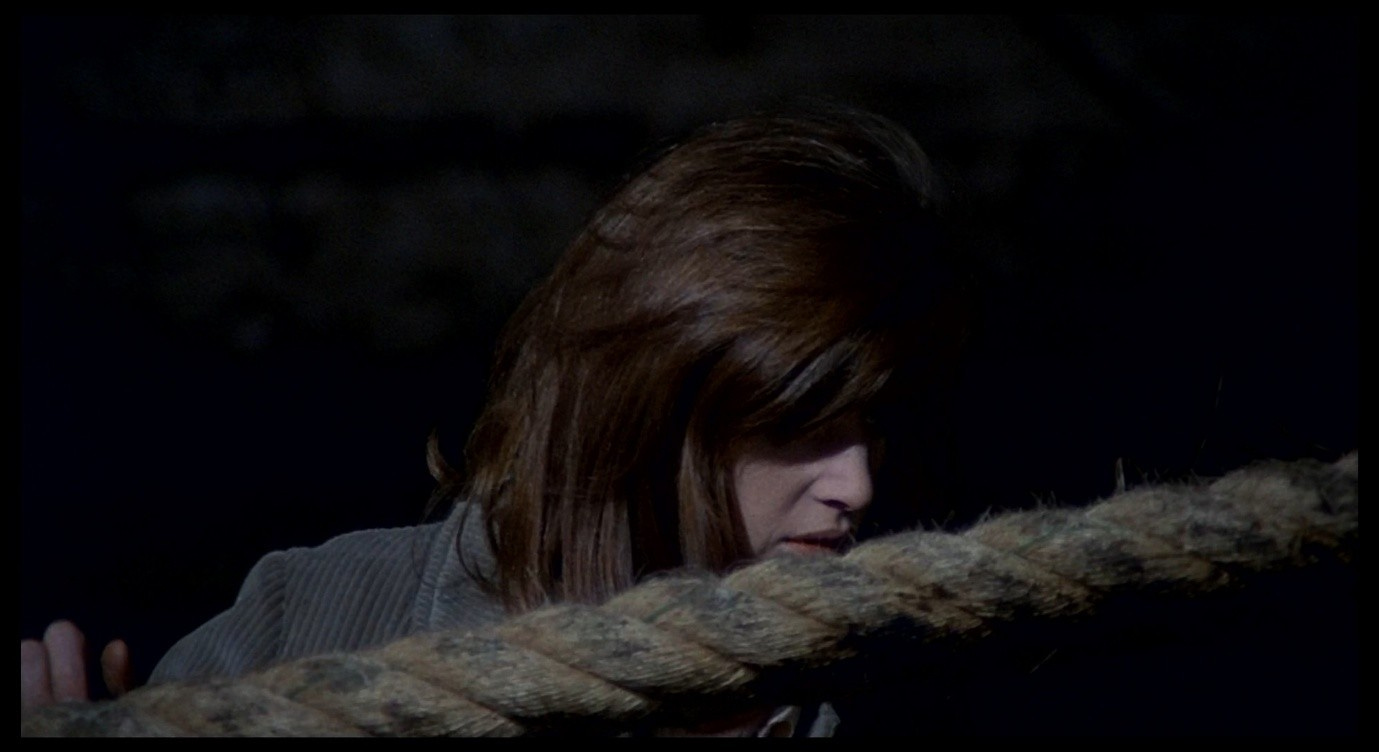

It is interesting that the screenplay attributes her determination to her ‘state of crisis,’ that is, to the very thing that has seemed to incapacitate her for most of the film. These images of Giuliana gingerly traversing the shipyard are evocative of both the crisis and her proactive attempt to address it. She is surrounded by trauma, decay, and damage, and frequently has to grab hold of ropes, pulleys, and other objects as she makes her way through this inaccessible landscape. These moments underline her vulnerability, but also her facility in navigating the environment.

Giuliana continues to be wary of her surroundings, of the squeaking rusted objects she steps on and the unnerving sounds in the distance, but she persists in engaging with them, in coming to terms with them.

A groaning call draws her attention away from the dock-water and she follows the call with a look of urgency in her face.

As it turns out, her intent is to board a ship, and thereby to remove herself from her present reality – her ambiente storico, as Corrado might say. Contrary to what she told Corrado earlier, she takes no possessions with her, not even a suitcase. She will not follow through on this drastic impulse, but her momentary urge to reject the world she lives in is a crucial element in the conclusion of Red Desert. What we see here is Giuliana embracing her identity as a broken, non-functional thing, as a discarded fragment in the red desert. She goes to the place where such fragments end up, to a ship that looks like it has seen better days. Unlike the first ship, this one is clearly not in the process of being restored.

In Corrado’s hotel room, looking at his map, Giuliana wondered if there might be a place, somewhere in the world, where she would ‘get better [stare meglio].’ Perhaps she goes to the docks and considers boarding the Turkish ship in the hope of relocating to a world where she would be defined as something more than a waste-product. Like her rejection of Corrado, this (intended) rejection of ‘reality’ is a powerful gesture.

Next: Part 46, Does this ship take people?

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

‘Antonioni discusses The Passenger’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 333-343; p. 343

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 495. My translation.

Calabretto, Roberto, ‘The Soundscape in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Cinema’, The New Soundtrack 8.1 (2018), pp. 1-19; p. 16

Calabretto, Roberto, ‘The Soundscape in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Cinema’, The New Soundtrack 8.1 (2018), pp. 1-19; p. 9

TLO (username), ‘Antifouling paint’ (thread), encyclopedia-titanica.org

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The event horizon’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 1-10; p. 8. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘L’orizzonte degli eventi’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 3-14; p. 11.

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 111

Schoonover, Karl, ‘Antonioni’s Waste Management’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 235-53; p. 235