Everything That Happens in Red Desert (46)

Does this ship take people?

This post contains some brief discussion of suicide, and spoilers for Germany Year Zero, Stromboli, Europa ’51, and Journey to Italy.

At this point in Red Desert, Giuliana is torn between two kinds of fear: fear of the thing she is escaping from and fear of the thing she is heading towards. This is the tension she will try to resolve in the final part of the harbour sequence, and it stems from a conflict we have seen developing throughout the film. The ties that bind Giuliana to her world are oppressive, even annihilating at times; yet she also feels hopelessly cut off from that world and longs for a firmer connection to it. The shipyard is a liminal space that both connects Ravenna to the rest of the world and facilitates an escape from Ravenna. This port is a defining feature of the industrialised city in which Giuliana lives, it has enabled Ravenna to become what it is – but its only inhabitant (in this scene) cannot speak Italian, is only here temporarily, and has an attachment to a different part of the world. This is the place where Giuliana’s paradoxical desire for attachment and escape will be resolved, in a suitably ambiguous manner.

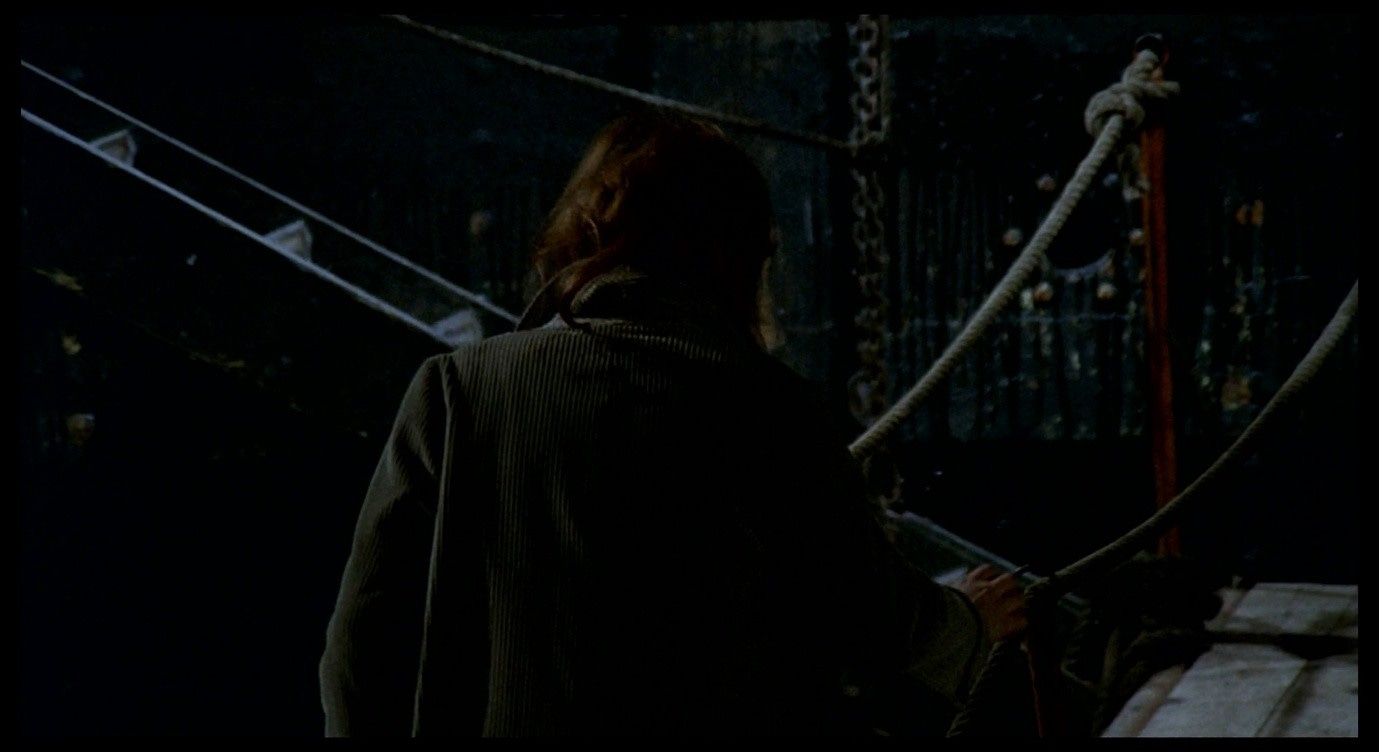

As Giuliana approaches the ship, she is alarmed by a loud bang, and looks over her shoulder to see where the noise came from.

She seems afraid of being pursued: the world she is escaping from may try to drag her back home. But she is also afraid of what she will find on this ship. She tentatively climbs a wooden ramp and pauses at the top where this ramp meets the metal stairs attached to the hull. She is alarmed again, this time by a clanking noise from above, and she grabs a nearby rope with her free hand to brace herself for whatever may descend the steps to meet her.

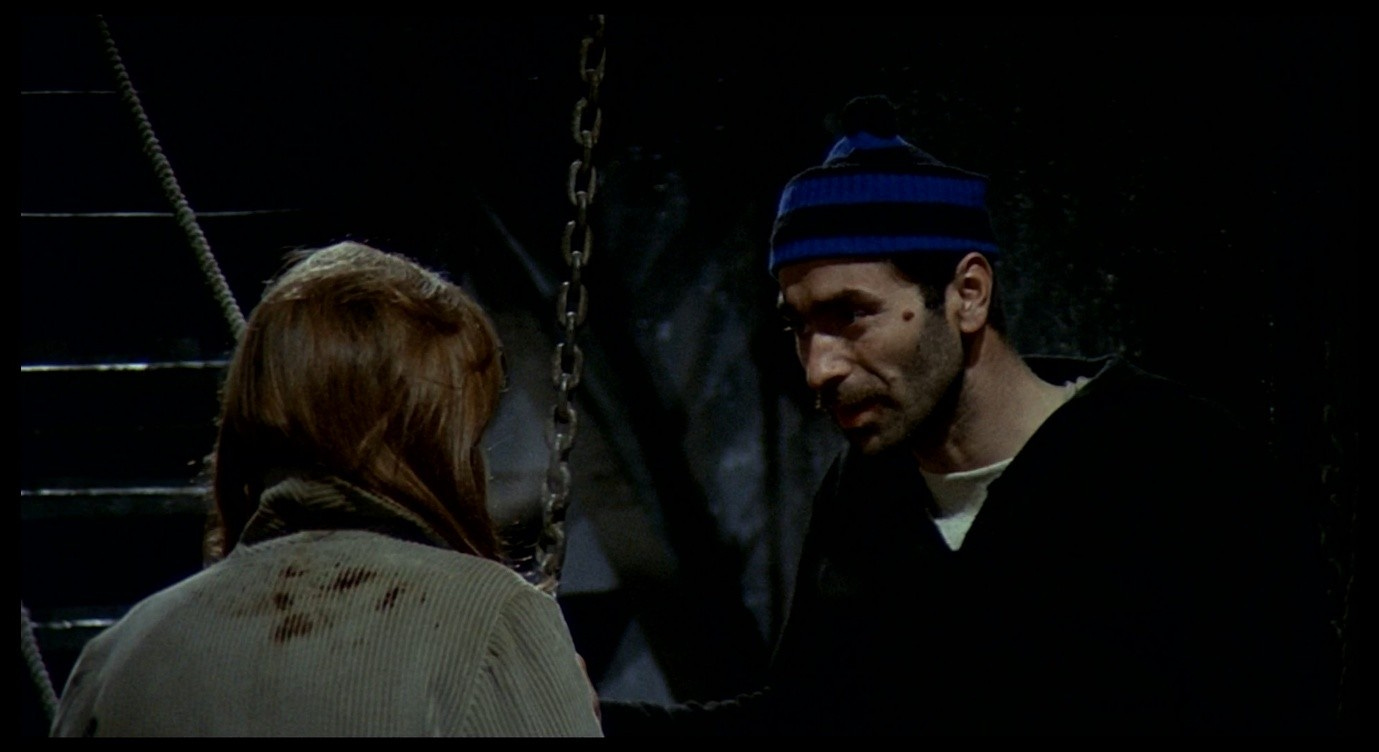

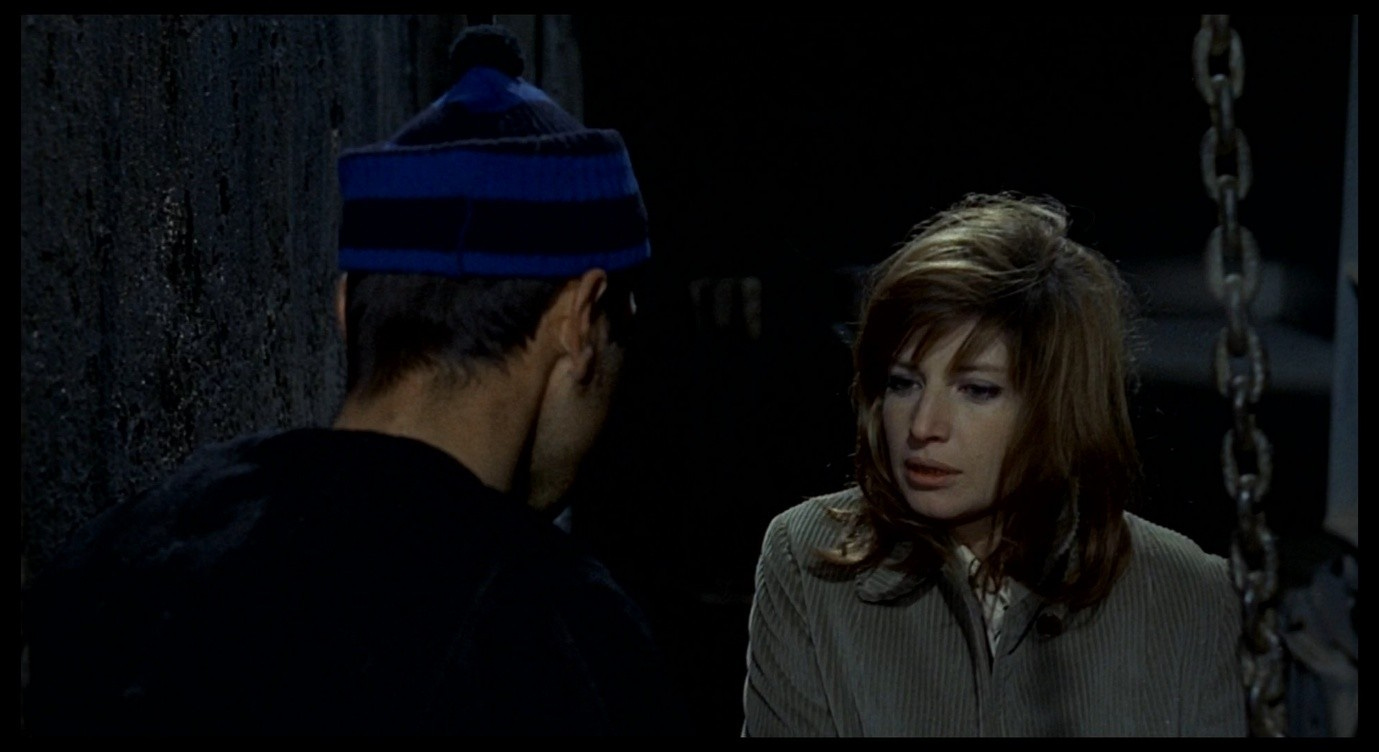

The noise was caused by a sailor removing the chain barrier at the top of the stairs. The down-to-earth ordinariness of this sailor, with his blue-striped cap, earnest expression, and slightly patronising tone of voice, disrupts the existential tone of Giuliana’s night-time odyssey.

She has traversed an alien-seeming landscape that resounds with strange noises. Now we see her framed against the dark (almost black) blue of the ship and the dark (almost black) shimmering water below her. Visually, her ascent of the gangway is also a descent into oblivion; there is something poetic about this gesture. But there is nothing poetic about the sailor. This is not because he is working-class: the shadowy river-dwelling figures in Gente del Po, the invisible spazzini in N.U., Aldo in Il grido, and Corrado’s recruits in Red Desert are all, to varying degrees, portrayed as inhabiting the poetically alienated plane of reality that Giuliana is locked into here. Like Ugo, or like the factory-worker who gave Giuliana a sandwich, the sailor is just a man going about his daily tasks, and is not at all conducive to her project in this moment. Just as she wilted in the face of Ugo’s common-sense suggestions and protests, and just as she walked sheepishly away from the factory worker, so she will end up retreating from the Turkish sailor, back into the poetic darkness.

First, however, she attempts to communicate. The sailor’s initial greeting – a simple ‘Good evening to you,’ if we understand Turkish – is spoken in the flat, unaffected style of a non-professional actor, like the tour guides in Journey to Italy. Giuliana stutters out a few incomprehensible sounds, which the screenplay renders more clearly as ‘Io… non può… io…,’1 recalling how her speech (and sense of self) disintegrated in the face of the hotel receptionist’s questions a few minutes earlier (see Part 36).

David Forgacs comments on Monica Vitti’s vocal performance here:

Vitti’s distinctive voice […] could be heard in its full expressive range when recorded through a studio microphone, more than when she performed on stage. […] In Il deserto rosso, for instance, when Giuliana tells her son Valerio the story of the girl on the island of pink sand, Vitti’s voice is almost hypnotic in its gentleness, whereas when she delivers her monologue to the Turkish sailor at the docks it is nervous and the speech is broken.2

The dialogue before the monologue is, in a way, the most impressive piece of acting in this scene. Vitti, speaking into the studio microphone in post-production, makes it sound as though she both does and does not understand the sailor, and as though she were both speaking and not-speaking to him. His words are just noises to her, yet she receives them as words. Her words disintegrate into noises, trying to meet his words half-way. She is not just mumbling incoherently: her utterances seem full of meanings that cannot quite be conveyed by the Italian language. Even during the tale of the pink beach, we heard her voice disintegrating towards this point, as her sentences became more disjointed and the imagery accompanying them became more abstract and, finally, blurred beyond recognition. Encountering someone who does not speak her language, Giuliana is prompted to peel back the veil of that language and to express something of what lies beneath it.

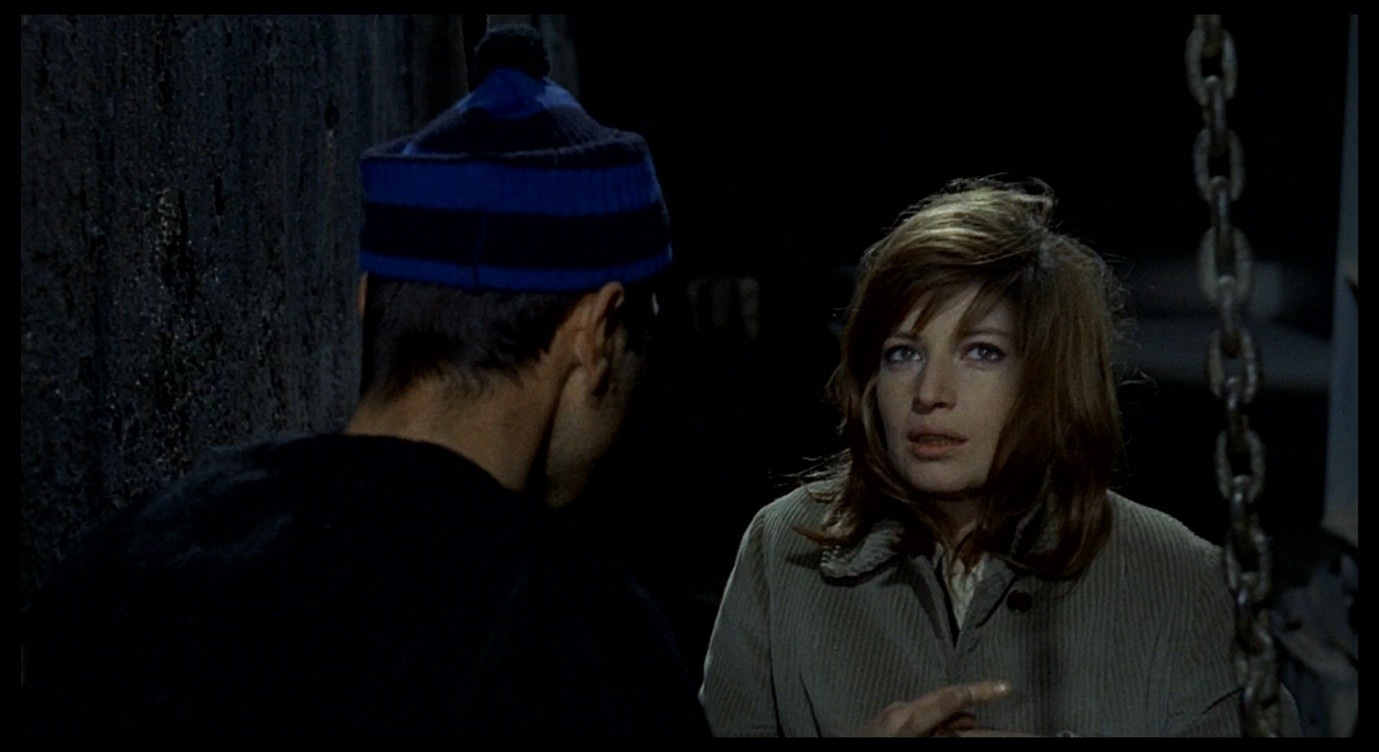

We see the sailor looking intently at Giuliana, trying to understand her, then we cut to a shot in which he is obscured behind the metal steps he has just descended, and she is isolated against the darkness on the right-hand side of the frame.

The image captures something about the failure of communication in this moment: Giuliana does not quite see the sailor, who is broken up by and conflated with the inanimate structures around him; the sailor sees her as a strange, out-of-place figure (de-inserted from reality) who does not belong here and cannot make herself understood.

As the camera frames them like this, Giuliana manages to get out a few words: ‘Excuse me, can you tell me…’ She seems aware that she is asking the impossible – he cannot tell her anything – and apologetic about this, but still cannot help but try.

As the screenplay says, ‘Giuliana does not understand, but needs to respond, to speak.’3 The sailor moves his face closer to hers and widens his eyes, attempting to speak clearly and convey his meaning in spite of the language barrier.

Whether we literally understand him or not (he is saying, in Turkish, ‘Are you looking for someone? Do you need something?’), it is clear that he is asking why she is here and that he is trying to be helpful rather than rebuking or threatening her. Giuliana continues to improvise, replying as though she understood his question, but also as though he had misunderstood her intent: ‘I didn’t want…’

After his next question (‘Do you want a coffee?’), she will respond with a similar denial, ‘No, it’s not that I have already decided,’ trying to exercise some control over the assumptions being made about her. This sailor cannot possibly be asking the right questions, because he cannot possibly understand what Giuliana wants, and yet Giuliana cannot give up on the attempt to convey her meaning. As the dialogue goes on, she nods encouragingly at the sailor, perhaps hoping that a mutual will to communicate will carry them through this exchange.

Her one coherent question, which literally translates as ‘Can people also travel on this ship?’ seems especially resonant given how de-populated this sequence has been until this moment, and in the context of Giuliana’s bedtime story to Valerio about an un-manned vessel (the vero veliero that on closer inspection became mysterious and unreal). She is asking whether the ship will take passengers as well as cargo, but her wording carries a more philosophical connotation: is it possible for a human being to exist here, or is this a space exclusively designed for inanimate objects? Is this an autonomous vehicle operated by robots or a possible avenue of escape for a living entity like Giuliana? Again, we should remember her reflections upon seeing Corrado’s map: she wondered whether there might be a place in the world where people go to get better. ‘Perhaps not,’ she concluded then, and here too she seems to realise that she is looking for a cure in the wrong place, or that there is no cure in any place.

This encounter with a mysterious stranger has several analogues in Antonioni’s work. Perhaps the most obvious and direct overlap is with The Passenger, in which David Locke repeatedly tries to communicate with people in spite of language barriers or more subtle cultural or circumstantial barriers that prevent understanding. At home, he feels out of place and unable to communicate except through inexplicable, disruptive gestures like lighting a bonfire in the garden.

His investigations as a journalist take him to places where he does not understand either the native language or the political context, and where he finds the scrutinising lens being uncomfortably turned back in his direction.

He assumes Robertson’s identity and then finds himself engaged in conversations where, although there is a common language, he has to guess at what his interlocutors want, and at how he should respond. Talking to the men who are buying his (i.e. Robertson’s) guns, Locke’s face has the unmistakable look of someone who cannot even begin to find the right words; his improvisations are painfully lacking in conviction.

Like Giuliana in the shipyard, he throws himself into situations that are, in various senses, foreign, seemingly in the hope of discovering a new kind of meaning, of escaping from the incomprehensibility of his home life. Like Giuliana, he abandons each escape attempt with a sense of jaded disillusionment.

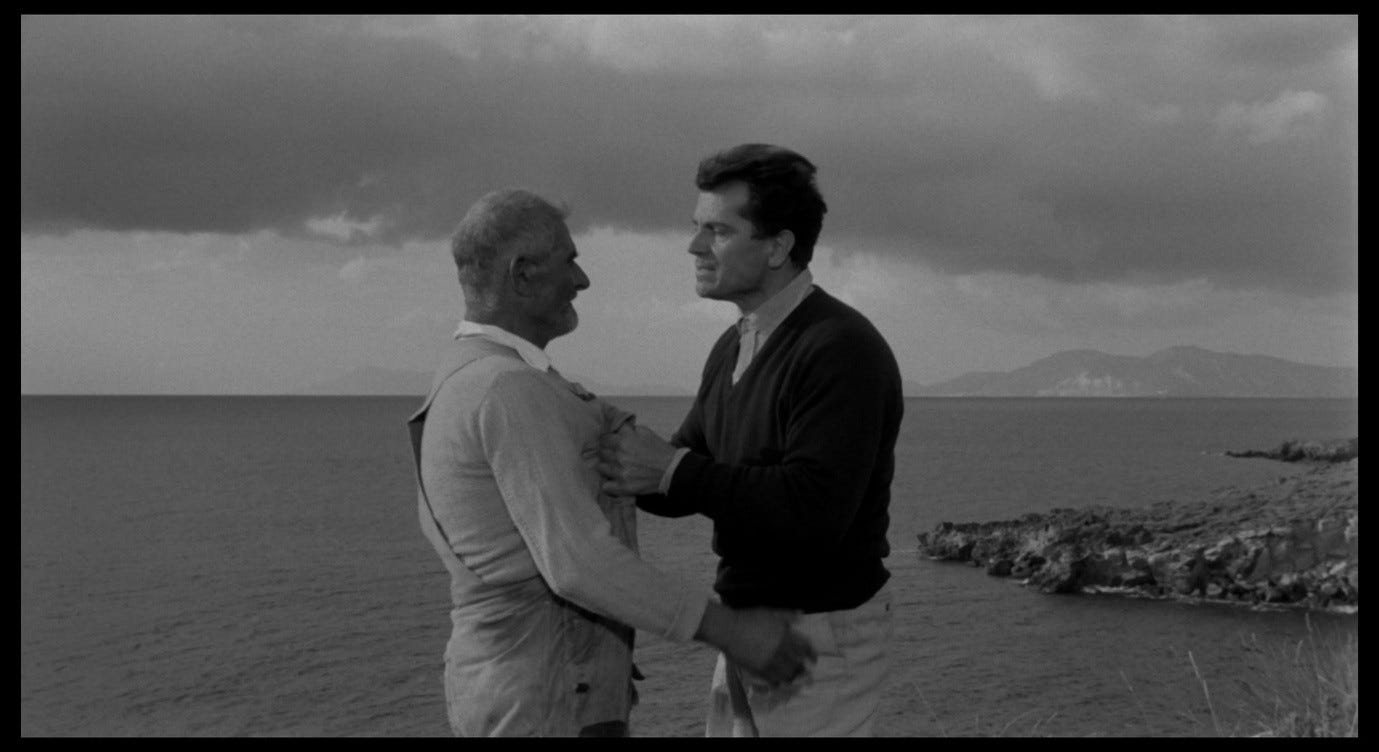

A less obvious, but I think more telling, parallel may be drawn with the old man on Lisca Bianca in L’avventura. He lives in a tiny shack embedded in the earth, in which the characters take refuge during their initial search for Anna. The old man is Italian but has recently returned from a 30-year stay in Australia, which he clearly considers his true home. Speaking English, he introduces his family members, represented by photographs on the wall.

According to Ian Cameron, this old man was an actual inhabitant of Lisca Bianca.4 Geoffrey Nowell-Smith says he lived in nearby Panarea, and that he insisted on speaking English so that his Australian relatives would understand his dialogue when they saw the film.5 Like the Turkish sailor in Red Desert, this old man is defiantly un-symbolic, a reminder that this setting is a real place where people live and work, however much it may appear to us as a landscape of the mind whose rocks and vegetation embody the loneliness of existence. As Seymour Chatman puts it:

None of [the information provided by the old man] has anything to do with Anna’s disappearance or, indeed, with anything else in the movie. The effect is realistic precisely because the information is gratuitous; the old man is not there to advance the plot. He is simply there, as one more of Antonioni’s stubborn ‘found objects.’ His Australian experience and the other details seem to be true because they have no reason not to be.6

And yet, in both L’avventura and Red Desert the down-to-earth stranger also serves to embody that existential loneliness. The old man on Lisca Bianca has returned to his native country and language but is now alienated from both. His attachments are far away, and the solitariness of this hut on this barren island is indeed reflective of his internal condition. He is a ‘found object’ like the island itself, a piece of reality whose very real-ness starkly exposes our broken relationship with the world and with each other.

Lisca Bianca is the place where Anna finally resolves her own sense of conflict between a longing for connection and a desire to flee her attachments. The old man may well have been the agent of her escape – it may be his boat we see in the distance just after Anna’s final appearance – suggesting that she was able to take that final step from which Giuliana retreats.

The old man does (albeit obliquely) convey some vital information about this place, and about Anna. He mentions that one of his lambs fell off a cliff recently, prompting Claudia to run out into the rain and scream for Anna, desperate for some sign that she has not fallen to her death.

Later, Sandro will angrily interrogate the old man as though he suspects him of having murdered Anna.

But both Claudia and Sandro are in denial. This lonely, dis-placed stranger is telling them something more disturbing about their vanished friend.

As ‘real’ and down-to-earth as these locations and these peripheral characters may be, they can prompt someone to become entirely dislocated from reality. For Anna, this was the place that enabled her to dissolve that reality – her identity, her personal connections, her possessions – and go in search of a new one. For Claudia and Sandro, encountering Lisca Bianca and the old man from Australia will call into question their own sense of the reality they inhabit. If Giuliana had boarded the ship and sailed away, her friends and relatives would search the docks and interrogate the Turkish sailor when he next stopped in Ravenna. They would not find a precise answer to their questions, but they might still find themselves disturbed by the atmosphere of this setting, and by the difficulty of communicating with this stranger who helped their loved one escape. Would these disturbed feelings bring them any closer to understanding Giuliana’s motives?

But of course, Giuliana does not board the ship. No one witnesses her abortive escape attempt except the sailor, who does not understand it. Then she returns home. In L’avventura, we stay with the characters who are groping their way towards understanding Anna’s crisis; her disappearance is a provocative and expressive act that somehow transforms the world that Claudia and Sandro inhabit. In Red Desert, we stay with a version of Anna who never literally vanishes, whose attempts at self-expression are ignored, but who is given a chance to explain her point of view – to us, and to no one else.

This stage in Giuliana’s odyssey also re-works the ending of Rossellini’s Stromboli, terra di Dio, in which Karin (played by Ingrid Bergman) finds herself living in an intolerable environment and ultimately tries to escape from it. The island of Stromboli is not far from Lisca Bianca, and both these Aeolian islands – though more atavistic and ‘trapped in the past’ than 1960s Ravenna – are comparable to Giuliana’s deserto rosso in their alienating effects.

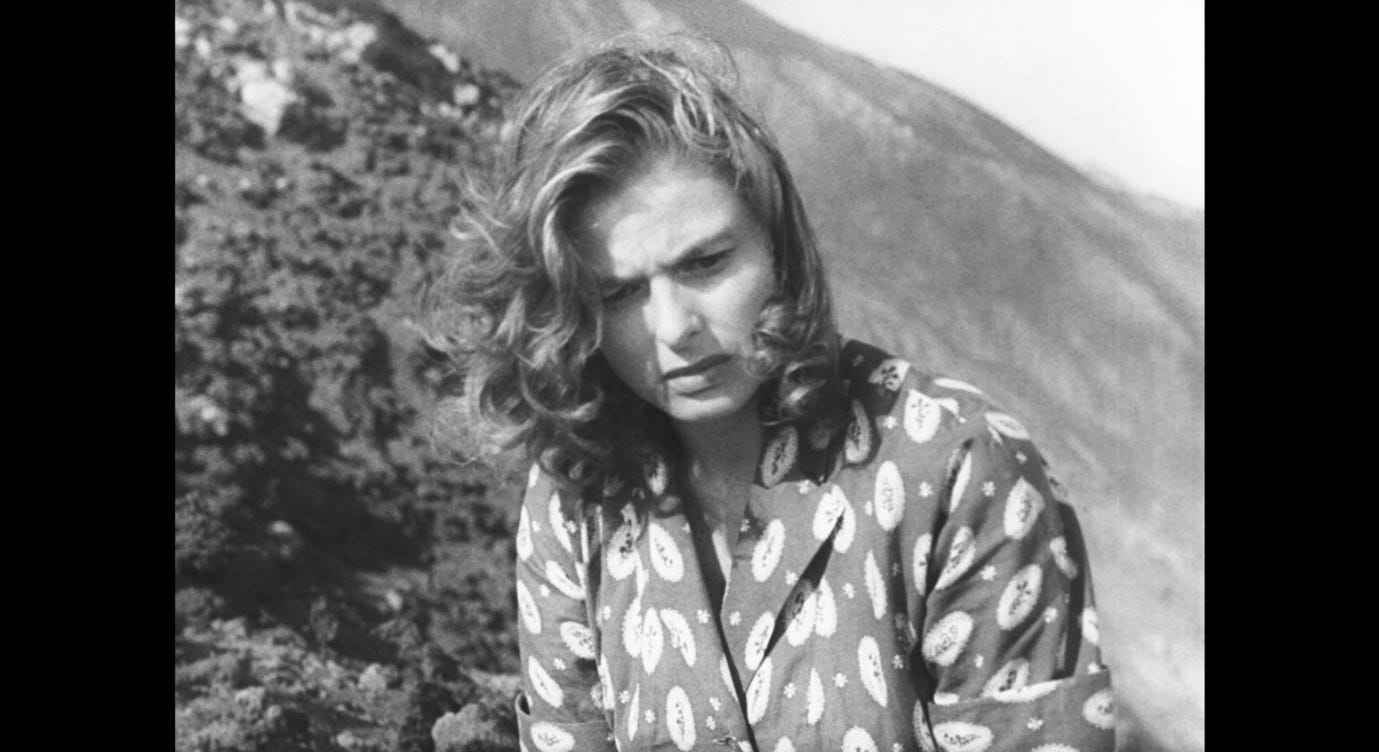

Karin’s conflict with her husband and his traditionalist neighbours (many of whom have returned to the island after long stays in Australia or America) is a battle to retain her dignity and agency in the face of endless material, tangible hardships. But this material conflict transitions, in Stromboli’s final scenes, into a more symbolic conflict with the island itself, as Karin flees upwards towards the volcano’s constantly erupting summit. Overwhelmed by poisonous smoke, she abandons her belongings and is reduced to her self alone.

The higher she ascends, the darker the volcanic desert around her becomes. As she looks beyond her immediate surroundings, there seems to be nothing but billowing smoke above and below.

She is no longer climbing a volcano, but struggling to cling to a single patch of black earth that is always on the verge of tipping her into oblivion.

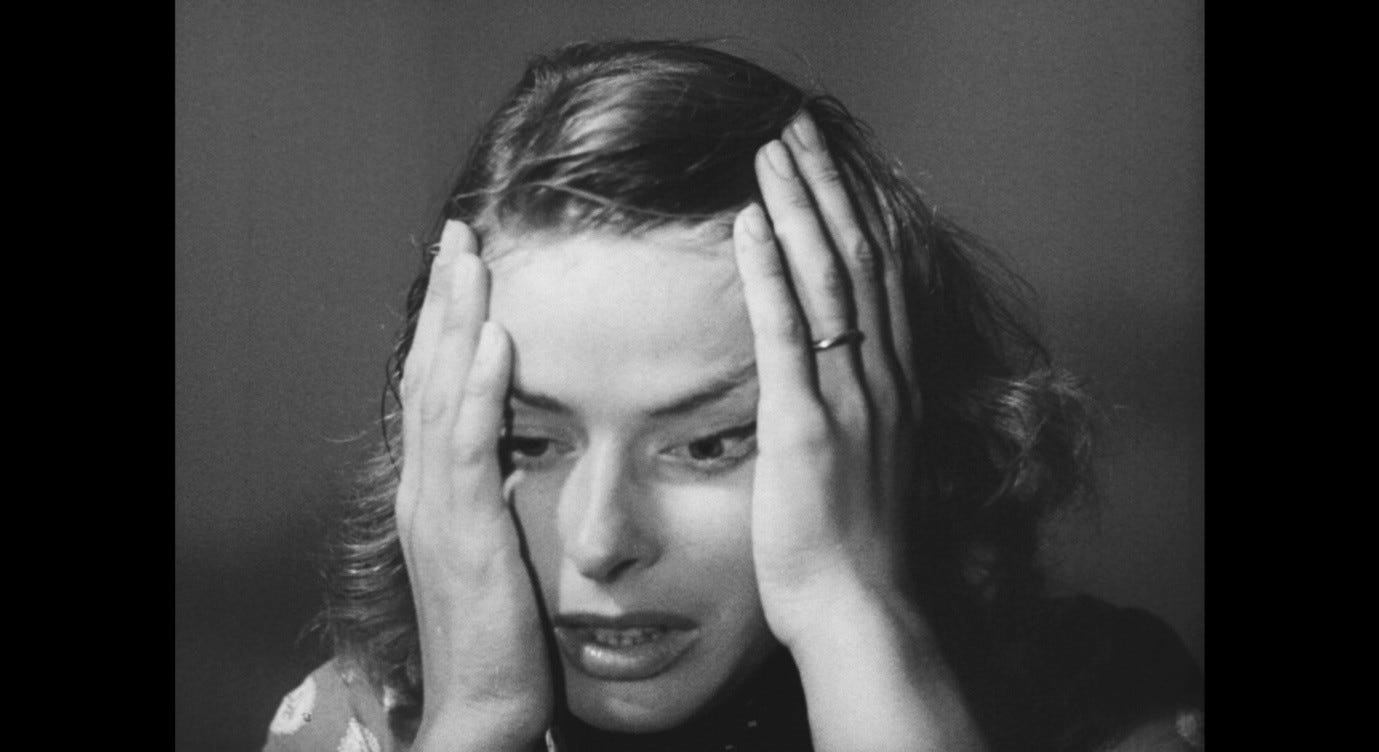

The ground repeatedly gives way beneath her, until at last she stares into the fiery abyss and cries, ‘Enough, enough, enough! I’ll finish it… I’ll finish it… But I haven’t the courage! I’m afraid, I’m afraid!’ In the Italian version, instead of ‘I’ll finish it,’ she says, ‘It would be better to die.’ Karin contemplates surrendering to the void and flinging herself into the volcano, just to bring her torment to an end.

But the dark earth itself – the terra di Dio referred to in the film’s title – and the starry sky above seem to lull her to sleep, and she wakes up the next morning to discover a different kind of overwhelming prospect. Light speckles in the ground mirror the stars she gazed at the night before, as if she were now among those stars, while the sky has been cleared and cleansed by sunlight.

‘What mystery, what beauty,’ she says. She vows not to return to her husband’s village, but we do not see the next phase in her journey. As far as we are concerned, Karin’s story ends in the desert. She gazes into the (now smoke-free) sky, and at the birds flying overhead, and calls on God to give her strength, understanding, and courage.

This biblical desert becomes a kind of testing-ground that activates both Karin’s self-sufficiency and her dependence on a higher power. Having suffered under the oppressive authority of her husband and the patriarchal norms of his village, she now frees herself from them; and having rebelled against that authority and those norms, she now subjects herself to the ‘merciful God’ who must redeem her. The film cannot show Karin accepting her life on Stromboli, nor can it show her escaping and gaining full independence. This insoluble tension drives the film’s intense but ambiguous ending.

To draw another comparison with L’avventura, this time we follow Anna’s escape from Sandro, but still never find out what happens to her. Rossellini is deeply invested in the transcendent emotion that Karin accesses, in her sense of contact with the divine, and in the idea that this religious experience comes from the earth of the volcano, moving through Karin and connecting her with the heavens. But what strikes me about this ending is its emphasis on renunciation: Karin seems to reject other people, her self, and the world, without having anything to replace them with.

Although she asks God for strength, understanding, and courage, her frantic cries of ‘God! God! God!’ in the final seconds of the film, as the frame is taken over by the sky and the birds, sound like death and dissolution. Karin is unable to tolerate the day-to-day miseries of her husband’s village; then she is unable to tolerate the Sisyphean labour of crossing the volcano; and finally, though she does not take her own life, she abandons herself to the state of limbo that remains her only choice, given the intolerable realities she must otherwise choose between.

If Karin’s journey takes her from the mundane to the transcendent, Giuliana finds it hard to escape the former and access the latter. Karin’s prayers are not interrupted by a bemused shepherd offering her a snack. If they were, she might feel very differently about the elements of earth and sky she is trying to commune with. Antonioni locates his characters’ crises in a deep existential malattia rather than in the complex social conditions that interest Rossellini, but he also throws the terror of that malattia into greater relief by depriving his characters of redemptive or tragic endings. Edmund hurls himself to his death in Germany Year Zero, and even this act of despair represents something hopeful about the nation’s future; Aldo waves at Irma then stumbles off the refinery tower in Il grido, and this tragi-comic act means nothing. Katherine and Alex are joyfully reunited at the end of Journey to Italy; Claudia resignedly strokes Sandro’s hair and says nothing at the end of L’avventura. Irene attains saint-like status in Europa ’51 and Karin finds God in Stromboli, both after renouncing their homes and husbands; Giuliana finds a Turkish sailor for whom her crisis has no meaning.

The pointed mundanity of this encounter, though comical on one level, accentuates the loneliness of Giuliana’s condition. Like Karin, she is on that patch of sloping, cascading desert-earth, torn between climbing onwards and slipping into the flames, but unlike Karin she has to be reminded that the desert is all in her head, and that her ‘reality’ is just an empty shipyard. Reality is just as intolerable for Giuliana as it is for Karin, but somehow, in this case, there is no more screaming to be done about it, no god to pray to, and nowhere to go but (for want of a better word) home.

Next: Part 47, Giuliana’s explanation.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 495

Forgacs, David, ‘Face, Body, Voice, Movement: Antonioni and Actors’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 167-182; p. 173

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 495

Cameron, Ian, and Robin Wood, Antonioni (revised edition) (New York: Praeger, 1971), p. 26

Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, L’avventura (London: British Film Institute, 1997), p. 79

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 76